Abstract

Social entrepreneurship is gaining unprecedented momentum in the recent years and it is overwhelming to learn how social entrepreneurs are able to create both social and economic value overcoming all odds and sustain and grow their ventures. Social enterprise can be a for-profit or a not-for- profit venture in their constitution. This research study presents a comparative case analysis of four social ventures two of them are not-for-profit organisations and depend mainly on philanthropic partners for funding. The other two are for-profit social ventures and create products and services which are commercially viable. Three of the founders are Ashoka fellows and one is a national award winning social entrepreneur, all based in India. Irrespective of the nature of enterprise, developing a viable business model is crucial for the sustainability of the venture. Analysis of these organisations’ business models reveals different patterns. The findings suggest that successful social entrepreneurial organisations proactively create their own ways to partner with multiple stakeholders who share their social vision ; deploy resources effectively as an integral part of the business model; and integrate the target group into the social value network.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

“Social ventures” typically led by inspired individuals—so-called “social entrepreneurs”—have attracted increasing attention recently as the most viable answer to a plethora of social problems faced by countries. Social entrepreneurs realise the opportunity in addressing the social problems, as there is a shift away from the public sector—governments and non-governmental organisations—to the private sector—businesses and individuals. The entrepreneur is incentivized to generate more profits and as more profit is made, the more the social problem is alleviated (Thompson and MacMillan 2010). The phenomenon of social entrepreneurship is now studied thoroughly both by academia and industry, so that successful models can be learned and replicated for greater good.

The significance of this study is that social entrepreneurship as a model for creating social and economic value, according to literature, is both underestimated and misunderstood (Harding 2004). Rigorous research, focused on supporting and strengthening the processes and techniques used by social entrepreneurs, is suggested. So far, a few operating methods, business models , and best practices have been identified (Roberts and Woods 2005). There is a need to investigate the structures created by social entrepreneurship, the co-operations and partnerships they engage in and the way they shape the value chains in the different sectors (Seelos and Mair 2005). This study is to explore the different business models of both for-profit and not-for-profit social enterprises and examine the suitability to their ventures. The researchers have chosen four Social Enterprises, of which two are not-for-profit organisations and other two are for-profit ventures. Three of the founders, Shanti Raghavan, Vishal Talreja and Ashwin Nayak are Ashoka IndiaFootnote 1 fellows and A. Muruganantham is a National award winning social entrepreneur (Table 13.1).

The structure of the paper is as follows:

-

Part I—Understanding the related concepts and the research methodology.

-

Part II—Description of the four organisations, their inception, value proposition , target customers and their business models .

-

Part III—Examine the social impact of their enterprises and evaluate the pros and cons of adopting certain practices.

2 Conceptual Background

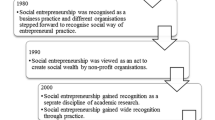

Social entrepreneurship means different things to different people with numerous definitions depending on the context in which the phenomenon takes shape. There are many terms interchangeably used in the research associated with social entrepreneurship like social change agents, community entrepreneurship, corporates social responsibility, social activists, social entrepreneurs, non-profit organisations, etc. Thus, the concept of social entrepreneurship is still poorly defined and its boundaries to other fields of study remain fuzzy (Mair and Marti 2006).

Late Professor Greg Dees Footnote 2 of Duke University, says social entrepreneurship is the pursuit of “Mission-related impact” (Dees 1998). The definition of social entrepreneurship combines value creation with innovation and change (Schumpeter 1951), pursuit of opportunity (Drucker 1985), and resourcefulness (Stevenson 1983).

The closer a person gets to stratify all these conditions, the more that person fits the model of social entrepreneur. As a result, social entrepreneurship has become so inclusive that it covers all socially beneficial activities. Most of the definitions seem to confirm that social entrepreneurs bring about transformation and acts as the catalysts behind social progress, while working hard to replace short-term charity with sustainable solutions (Braunerhjelm and Stuart Hamilton 2012).

For the purpose of this study, social entrepreneurship is defined as follows:

‘Social enterprises are businesses with primarily social objectives whose surpluses are principally reinvested for that purpose in the business or in the community, rather than being driven by the need to maximise profit for shareholders and owners’. According to Department of Trade and Industry, UK they tackle a wide range of social and environmental issues and operate in all parts of the economy, and use business solutions to achieve public good (Department of Trade and Industry 2012).

2.1 Business Models in Social Entrepreneurship

The term “business model” is sometimes a sketchy term. According Zott et al. “though academics around the world have moved towards simplification of a business model, the term often used out of context has led to it becoming often confused as a concept. At a general level the business model has been referred to as a statement (Stewart and Zhao 2000), a description (Weill and Vitale 2002), a representation (Morris et al. 2005), architecture (Osterwalder et al. 2005), a conceptual tool or model (Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010) etc. This term was defined and used differently, to encompass anything from structural elements to agent interaction (Zott and Amit 2007) or knowledge leverage (Shane and Venkataraman 2000; Zott and Amit 2010)”.

More evolved and sustainable business models is now a prerequisite or necessity, if a social entrepreneur would want to expand its scale, raise venture capital funding, or reach more beneficiaries . Based on the literature review the researchers have narrowed down two seminal works on Business Models, Alex Osterwalder’s Business Modelling of nine building blocks (Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010) and Four Lenses Strategic Framework ’s Business Models for Social Entrepreneurs (Alter 2010). This study is based on the models described in these articles.

3 Problem Statement

From an extensive literature review the researchers narrowed down two critical problems as described below as areas for this study.

In order to create a successful and sustainable social enterprise, the social entrepreneurs need to fine-tune their business models and successful social entrepreneurs are constantly seeking novel and unique business models, so that they can increase their social impact .

3.1 Research Objectives

This study explore the different business models of social enterprises and examine the suitability to their ventures. In-depth examinations of their business models reveal that based on the type of social venture, they require appropriate business models and may not have a standard format. A study of this nature would throw light on the strategies on viable business model/revenue model which are imperative for successful social entrepreneurship . The major objectives of the study are,

-

1.

To explore the business models adopted by social ventures (for-profit and not-for profit),

-

2.

To understand the measurement of social impact of the venture,

-

3.

To develop a conceptual model of sustainable business model.

3.2 Research Methodology

The methodology undertaken in this study consisted of a combination of desk-based research, and a series of personal interviews. Various research journals on entrepreneurship, social entrepreneurship and general management are reviewed to understand the various conflicting concepts associated with social entrepreneurship. “Multiple case study method is used to understand complex social phenomena and is applicable when a contemporary phenomenon is being investigated within its real-life context, when the boundaries of the phenomenon and the context are not clearly evident, and when multiple sources of evidence are being used. Critics typically state that single cases offer a poor basis for generalizing. However, such critics are implicitly contrasting the situation to survey research, in which a sample is intended to generalize to a larger universe. This analogy to samples and universes is incorrect when dealing with case studies. Survey research relies on statistical generalisation, whereas case studies (as with experiments) rely on analytic generalisation. In analytical generalisation, the investigator is striving to generalise a particular set of results to some broader theory (Yin 2014)”.

The four social entrepreneurs discussed in this study were suggested by a social venture capitalist. Expert opinion is one of the preferred methods (Mair and Marti 2006) to identify the samples in a multi-case study method . These four organisations represent various sectors like health, education, livelihood etc. They also are of varied scale, target groups and customer segments. The four case studies have been analysed based on Osterwalder’s Business Model’s major three building blocks which are:

-

Value Proposition , which include products and services,

-

Customers who consist of target group, distribution channels and customer relationship,

-

Infrastructure , which include core capabilities and partners network,

-

Cost and revenue model.

Apart from these key parameters which help to measure the effectiveness of Business Model, to have a comprehensive understanding, the following details are also described:

-

Entrepreneurial story and motives,

-

Vision and mission of the social enterprise,

-

Social impact or outcome created,

-

Issues and challenges of the enterprise etc.

3.3 Limitations

Since the sample size is limited to four social entrepreneurs, the study may not represent the general characteristics of social entrepreneurs. Most of the information collected for this study is based on personal interviews with the founders and secondary data available in their websites. Interviewers’ and founders’ bias and limitations of capturing the dynamics of a social enterprise through a limited number of questions might have crept in.

4 Case Studies of Not-for-Profit Ventures

4.1 Case Study 1: EnAble India

Founders: Shanti Raghavan and Dipesh Sutariya

(Website: www.enable-india.org)

4.1.1 Entrepreneurial Story

Shanti Raghavan, founder and Managing Trustee of EnAble India, narrates how she helped to cope up her brother who lost his eyesight at a very young age and realised how many such persons with physical disabilities (PWD) are ignored by our society. This motivated Shanti to give up her plum job in an IT company and founded EnAble India as an NGO . Since its inception, the vision of EnAble India has been to strive for the economic independence and dignity of those with disabilities.

Initially EnAble India had a single room and a few computers donated by her friends and acquaintances for their operations. The activities included computer training for the blind, parents’ workshops and transcription services, etc. The focus was on people with vision impairment and to place some visually impaired candidates in jobs, but soon she found it impossible to provide them full-time jobs. This lead them to create a model that is unique to EnAble India where the focus is not only in enabling persons with disability by giving them training and employment but also sensitizing employers to the business case of employing them.

4.1.2 Mission and Vision

Mission : EnAble India’s mission is to empower persons with disability . The mission is founded on the firm belief that the disabled do not need sympathy—they need a supportive environment to grow and fulfil their needs, potential and dreams. EnAble India's core activities are employment of people with disabilities, pre-employment services, supplemental education, counselling and support services, consultancy and training for other institutions and NGO s and technology services. EnAble India trains and counsels persons with disability and prepares them to join the mainstream workforce as confident individuals (www.enable-india.org).

4.1.3 The Value Proposition

The initial training programs developed by EnAble India focused mainly on developing computer-based skills with the help of self-paced exercises and tactile diagrams. From 2005 to 2007, the operations expanded significantly with employability training, computer training and placements across multiple cities including Delhi, Mumbai, Hyderabad, Kolkata and Pune. EnAble India is now operating from one administrative office and three training centers. This has given the much-needed momentum and scale required for expanding activities in the form of Training, Employment Guidance and Placement (EGP). EnAble India recently released an “Automation Tool 1.0 version which enables the trainee to learn the Computer Basics, MS word, Excel, and Internet concepts on their own, without trainers’ intervention (www.enable-india.org). EnAble India is now working as a placement cum training agency for the Government of Karnataka and its working is recognised on multiple central Government platforms involved in technological research in disability space. The organisation has developed a model in respect of inclusion of existing employees at State Bank of India. It has also started a programme for training persons in Autism spectrum and out of a batch of 10 such candidates 6 have already found employment with SAP Labs.

4.1.4 Target Market

EnAble India has a set of multiple stakeholders to address which include,

-

Persons with Disabilities

-

The Companies which recruit them and,

-

Funding organisations

The PWDs, who register with EnAble India are enrolled in an 8-month training programme that teaches them computers, life and soft skills and a walk-by of different industries. When a suitable vacancy shows up, the candidate is offered a more specific orientation of his new job. While some of the companies like IBM act on their existent diversity policies (encouraging a more heterogeneous workplace), for others it is part of in-house Corporate Social Responsibility, while the remaining recruitments are motivated by goodwill.

4.1.5 Infrastructure and Partner Network

EnAble India works with a complex list of stakeholders and partners network . From funding agencies, Government departments, organisations’ CSRs, volunteers , parents of PWDs, and the companies where the PWDs are placed, the list is endless. In the past 10 years, EnAble India has placed about 1,200 individuals in companies like Accenture, IBM, Shell, Goldman Sachs, Big Bazaar and others, from housekeepers to brew masters, software engineers and quality analysts. Currently EnAble India has directly placed 1,250 plus persons with Visual Impairment, Hearing Impairment, Physical Disability, Muscular Dystrophy, Cerebral Palsy, Development Delays and Mental Illness. They also work with various NGOs to source these students. The core focus of EnAble India is to open up companies and jobs. This benefits not only candidates to get jobs on their own or through referrals but enables companies to hire persons with disability and also other NGO’s to enable their beneficiaries. The solutions oriented approach of EnAble India has opened up jobs for candidates with profound disability and newer opportunities and roles for others. 93 % of companies who have hired their candidates have said there has been a high impact by hiring persons with disability.

4.1.6 Finance: Revenue Model and Cost Structure

EnAble India has multiple revenue streams which are,

-

Donations from individuals and Institutions,

-

Professional charges,

-

Recruitment income and

-

Training and seminar fees.

Individual Donors: EnAble India has always relied more on donations due to word of mouth of the work. Hence individual donors play a very big part in giving the support. They even get donations from their own candidates and students which is a validation of their work.

Institution Donors—Major Ones

-

Axis Bank Foundation

-

Sir Dorabji Tata Trust

-

Tech Mahindra Foundation for the E-Vidya project, to make the employability training to every individual candidate with disability across India.

-

Sir Dhun Pestonji Parakh Discretionary Trust funds the Children Services and Early Intervention programme for Visually Impaired Infants and Children.

-

Charities Aid Foundation (Accenture and Microsoft)

-

American Aid Foundation

-

State Bank of India

-

Department-Empowerment of Differently Abled & Senior Citizens- Karnataka Govt.

They also have many eminent partners with whom they collaborate to create curriculum, material support, profiling candidates, imparting training etc.

4.1.7 Social Impact

See Table 13.2.

4.1.8 Sustainability and Business Model

Major source of funding for EnAble India are individual and institutional donors. With the help of Sattva, a social enterprises consulting firm from Bangalore, the couple is establishing another entity named, EnAble India Solution Private Limited, a for-profit arm of the trust , which is on the lookout of multiple revenue sources, by encashing the existing competencies of EnAble India.

4.1.9 Challenges and Future Plans

According to National Centre for Promotion for Employment for Disabled, (NCPEDP) in India there are 70 million people with disability. But the companies in private sector hardly hire them. A corporate survey conducted by NCPEDP in 2000 showed that the cumulative average of disabled recruitments in 70 companies was 0.4 %. It also showed that the average employment rate of disabled people in the private sector was only 0.28 percent. The public sector showed an employment rate of 0.54 percent and in multinational companies it was a mere 0.05 percent.

Sensitising the companies towards employing PWDs would have to be taken at a bigger scale as the number of trained PWDs increases year after year. Both Shanti and Dipesh are confident in changing the current charity model to a profit based business model through their new entity which can help the foundation to provide better services to the trainees like hostel accommodation, (which is currently not offered) better training facilities, conducting more outreach programmes etc and scaling their operations across India.

4.2 Case Study: Dream A Dream

Founder: Vishal Talreja

(Website: www.dreamadream.org)

4.2.1 Entrepreneurial Story

Vishal Talreja, an academic topper and an active student leader both in his university and also with an international association of students in economics and management, spent three years in the corporate sector with Xerox and Technology Holdings after graduation. It was during this time that he visited Finland on an exchange programme and met several students from different parts of the world. He noticed how these countries unlike India, have a strong social welfare system and the people took a pride in who they are and what they did. This was a totally new experience for him and shaped his life choices thereon.

He remembers that during his childhood he was not allowed to play with children in his neighborhood who came from poor families. He realised this came from the generations of prejudice and preconceived mind-sets and must be changed first. Talking to several friends and colleagues on this need for social change created a “powerful desire to make a difference in their communities”, Vishal co-founded “Dream A Dream” in 1999 along with eleven other co-dreamers. Although the co-dreamers were a hearty mix interesting individuals from different backgrounds viz., contemporary dancers, photographers, management graduates, software engineers, counselors, chartered accountants, future business tycoons and ad professionals, the common dream that held them together being “wanting to give back to the community.” Having brought up in a conventional family where academics are given utmost importance, for Vishal, education for children was a natural choice to do something for the society. “To change the future of the country, you need to work with children!” he said.

4.2.2 Vision and Mission

According to UNICEF 2005 report, India is a country with 35 million orphaned children of which 18 million are street children. Dream A Dream noticed a critical missing link of meeting the developmental needs of this large group of vulnerable children in India. This need is fulfilled through a dual approach, “to empower children from vulnerable backgrounds by developing life skills and at the same time sensitizing the community through active volunteering leading to a non-discriminatory society where unique differences are appreciated”.

4.2.3 The Value Proposition

Dream A Dream “improves the quality of lives of children from vulnerable backgrounds through non-traditional education to allow them to explore, innovate and build important life skills” (www.dreamadream.org). They give access to art, music, theatre and sports to not only build critical life skills to these children but also to provide an avenue for a professional career in any of these areas.

The value proposition of Dream A Dream are a set of programmes that allow children to develop:

-

“Interpersonal skills including teamwork, communications, negotiation and coping skills.

-

Cognitive skills such as decision-making, problem-solving and critical thinking.

-

Creativity, confidence, self-awareness and a passion for learning”.Footnote 3

This would require constant innovation to find and develop new and effective approaches to provide this values to children.

4.2.4 Target Group and Partner Network

Dream A Dream from the beginning recognised that developing life skills of children from vulnerable backgrounds and inclusive communities is very critical. These children are from migrant families, daily wage labourers living in urban slum communities or orphaned, abandoned or runaway from home. They achieve this through strong long-term partnerships with multiple organisations and institutions that are interested in children’s issues.

The four key programmes offered by Dream A Dream are:

-

1.

Dream Life Skills Programme for 8-14 year olds

-

a.

Through Sports, using football as a medium to develop abilities for positively dealing with life’s challenges.

-

b.

Through Arts for interactive sessions where young people use art and craft to express and engage effectively.

-

c.

Dream Outdoor Experiential Camps, where outdoor camps build self-esteem and team work in participants.

-

d.

“Dream Fundays” Dream Fundays, where young adults learn through interactive engagement programmes with volunteers.

The Dream Life Skills Programme currently engages with 5,500 young people in 8–14 year age group in partnership with 29 NGOs. They have 170 batches running across the city of Bangalore. Each batch has 25–30 young people and each batch receives 2-hours of intervention once a week. The programme is delivered as an after-school intervention between 2:30–6 pm. Both boys and girls participate in the programme with 43 % girls participation.

-

2.

The Dream Connect Programme is designed for 14–19 year olds for career development. It offers the tools and foundational life skills that help transform ability to capability through short-term modules in spoken English, communication skills, money management skills, career guidance and access to internships/scholarships/job programmes. Additionally, if provides linkages and placements with the Industry with partnerships with vocational and job training programmes. It currently engages over 3,000 young people a year.

-

3.

Teacher Development Programme aimed at empowering adults that work with young people in both formal and non-formal spaces with life skills. The training is focused on the teacher/facilitator/instructor/trainer and developing their capability and ability to engage with young people effectively. It covers core elements of building personal connections, developing ability for deep listening, building safe learning environments and consistently reflecting on one’s own actions and behaviours that are shaping the behaviours of young people. Currently, over 1,000 teachers/youth workers are trained and impacting nearly 50,000 young people.

-

4.

“Dream Mentoring Programme”, where a caring adult volunteer mentor encourages young adults to find answers to the challenges of growing up through a one-on-one relationship. The Dream Mentoring Programme engages over 100 young people a year through an intensive 6-month to 1-year mentoring relationship with a volunteer.

These programmes are delivered with an active and commitment engagement from local volunteers and corporate support. Over 2,000 volunteers engage with Dream A Dream every year clocking over 25,000 hours thus helping to deepen the impact and also build a more aware and sensitive community.

There is a clearly defined memorandum of understanding to define the roles of each partner. Their partner networks are,

NGO Run Schools: Since 1999, about 30,000 children from twenty nine NGOs that Dream A Dream have partnered with, have been impacted through the life skills programme. They partner with orphanages, residential institutions, community centres and other regular schools that cater to needs of these children.

Curriculum partners: Dream A Dream has worked with PYE GlobalFootnote 4 and Grassroot SoccerFootnote 5 to develop Life Skills Curriculum and worked with Dr. Dave Pearson and Dr. Fiona Kennedy to develop a Dream Life Skills Assessment Scale (DLSAS) which has been published at http://sbp-journal.com/index.php/sbp/article/view/3518.

Community volunteers : Volunteer involvement is undisputedly directly proportional to the growth. Dream A Dream now has over 2,000 active trained volunteers contributing over 2,500 hours. These volunteers are trained through activities discussions and workshops.

4.2.5 Finance: Revenue Model and Cost Structure

In the initial years the founding members raised money from both social and corporate networking. Today, financial support comes in the form of donations, their fundraising events and programme grants.

4.2.6 Social Impact

Their impact assessment is primarily related to their mission and to measure the effectiveness of their programmes. Since 2007, Dream A Dream devised its own Life Skills Assessment Scale. This scale is used to track the development of life skills in all Dream A Dream programmes. A child’s progress can be measured in five categories, interactions with others, overcoming difficulties and solving problems/age appropriate independence, taking initiative, managing conflict and understanding/following instructions. In early 2014, this scale was published in Social Behavior and Personality, an International Journal and has been recognized as a standardized scale to measure Life Skills.

By 2013–2014, Dream A Dream:

-

1.

Impacted 5,500 children through its After School life skills programmes.

-

2.

Trained 510 teachers/educators in the Life Skill Model of Learning impacting 50,000 young people through partners.

-

3.

Over 2,000 volunteers have clocked 25,000 hours of active volunteering (Table 13.3).

4.2.7 Revenue Model and Sustainability

The growth of the organisation to bring transformative effect to over 2,000 children rests on the design of the approach that Vishal adopted. His first initiative is to encourage well-trained and committed volunteers to initiate and implement effective projects. The second initiative is to build strong partnerships to develop programmes in life skills. Thirdly, his revenue generation is through several sources including a substantial amount raised from individuals and businesses in the community. Dream A Dream also believes in building working relationships with all stakeholders that is sustainable; finding lasting and mutual solutions to share risks and responsibilities. There are also efforts being made towards good governance and to build robust systems and processes to manage finance, Human relations, volunteers and fundraising.

4.2.8 The Challenges and the Future

Dream A Dream is preparing for scaling its programmes to reach out to 2,40,000 children by 2015. Currently they focus on curriculum development , training module development and prototype the scale model. Vishal has a national vision for Dream A Dream. Vishal and team are now working towards building a committed and dynamic organisation capability to expand to other cities, towns and villages.

5 Case Studies of For-Profit Social Ventures

5.1 Case Study 3: Vaatsalya Hospitals

Founders: Ashwin Naik and Veerendra Hiremath

(Website: www.vaatsalya.com)

5.1.1 Entrepreneurial Story

After earning a Master’s Degree from the University of Houston, Dr. Ashwin Naik joined Triestaa Sciences, a clinical research organisation that conducts advanced research in Genomics in the field of Oncology. He then scrapped the idea of joining Sloan School of Business, when travelled around rural and semi-urban areas in India to collect data for Triestaa and visited some doctor friends. During this time he noticed that these hospitals lacked the basic standards and the seeds for Vaatsalya (Maternal Love) were sown. His college friend Dr. Veerendra Hiremath partnered in this venture. With his medical background, experience of living in US for 6 years, working on large projects, it was easy for Ashwin to identify the gap in the health care that was available to the Urban and rural India. Initially, the funding of $150,000 for this venture came from the NRI friends and relatives of the founders, many of who had roots from small towns and villages and Vaatsalya was set up as a private limited company in November 2004 and the first of the Vaatsalya hospitals was opened in Hubli in 2005.

5.1.2 Vision and Mission

The goal is to spread the network of hospitals across the country, focused exclusively on India’s rural and Semi-urban towns and revolutionise health care in India to provide primary and secondary care at very nominal cost to the middle and low income families. With a service motto—“The new FACE of health care, with emphasis on friendly service, affordability, cleanliness and efficiency”, Vaatsalya remains committed to business integrity, quality and sensitive to the needs and expectation of Doctors, customer, investors and community. The mission is to earn trust , every way, from customers and their families. By doing this well, Vaatsalya intends to build the foundation for long-term, sustainable growth.

5.1.3 The Value Proposition

Vaatsalya hospitals are 50–70 beds in size, with Neonatal Intensive Care facilities, Operation theatres, Maternity Room, Intensive care facilities, a mix of general rooms (dormitory style), and private/semi-private rooms. In addition there is a 24/7 pharmacy, basic laboratory and diagnostics facilities Specialties include, Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Paediatrics, General Medicine, General Surgery, Nephrology and Diabetology. (source: www.vaatsalya.com). Vaatsalya has created India’s first network of a chain of low-cost, no-frills hospitals by providing low-cost but high-quality,

-

Primary health care providing basic health facilities for common and minor ailments, that may be attended by a multi-competent physician and,

-

Secondary health care services for conditions requiring constant attention including short period of hospitalisation.

These two set-ups are complemented by a set of spokes focused on day care and prevention. The main differentiating factor of Vaatsalya as against the existing hospitals was the caring nature of doctors and nurses and the comfort level they brought to the patients.

5.1.4 Target Market

According to the founders, “In India, 80 % of health-care facilities is located in urban areas even though close to 70 % of the total population resides in villages and small towns.” Vaatsalya bridges this gap and focuses on the semi-urban and rural population that has limited access to good quality healthcare services. The idea was to make health care accessible and affordable to families who typically earn between Rs.6,000 and Rs.20,000 a month in the rural and semi urban areas. Vaatsalya provide affordable health care services to thousands of families across Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh through their hospitals in Hubli, Gadag, Bijapur, Mandya, Hassan, Mysore, Gulbarga, Shimoga, Tarikere, Malur, Chikmagalaur, Vizianagaram, Narasannapetta, Ongole, Anantapur, Hanamkonda and Proddatur.

The initial entry to this sector was challenging as the patients were reluctant to get treatment from hospitals as they perceived it as expensive and thought that they may not get personal attention from the doctors, and were unwilling to forgo the relationship with the local doctors. One of the important dimensions of Vaatsalya’s operations is the long-term relationships that its doctors develop with the patients. Therefore, Vaatsalya had to break that myth and work towards building trust and confidence of the local community.

5.1.5 Infrastructure and Partner Network

Apart from getting into partnership with local medical practitioners, to achieve its vision and create a positive social impact ; Vaatsalya’s also had to satisfy their investors’ requirements of good return on investment. Investment from Venture capitalist is not so common for social ventures, but Vaatsalya has shown that profits can be generated with relatively low investment, with innovation in the form of low-cost operating model along with enormous market potential to grow.

Some of Vaatsalya’s funding partners apart from family and friends who were angel investors in the initial stages are Aavishkaar fund, Seedfund, Oasis Fund (Bamboo finance) and Aquarius India Fund. Vaatsalya has raised a cumulative amount of $17.5 million through private equity capital since its inception in 2004.Footnote 6

5.1.6 Finance: Cost Structure and Revenue Model

The success of Vaatsalya’s business model is due to two reasons—one keeping costs low and generating revenue. After experimenting with three models of different capacity size and three different locations, they came to the conclusion that, to keep costs low, they need to maintain 50 beds per hospital (in the categories of general, private and critical care beds), which are leased instead of buying. Locating them in semi-urban and rural areas gave the advantage of lower rentals and hiring support staff locally were other ways of lowering costs further. The only expense that they did not compromise was the salary of the doctors. According to Naik, they required about INR 10–20 million to set up the hospital and about INR 1.5 million per month as running expenses, break-even to be achieved in 2 years. The set-up costs are reasonable as they own very less equipment like X-Ray machines, ultrasound and ventilators. They do not offer any complementary facilities such as a cafeteria. All its procurements are in bulk as it is centralised and results in better bargaining power with savings of more than 20 % of the cost.

A nominal fee is charged for all general consultations. Maternity, surgeries, physiotherapy, laboratory and diagnostics and childcare services are also charged at an affordable rate. The bed charges are kept very nominal. Each hospital has its own management team and is responsible for generating revenue like a profit centre. Apart from consultation and surgeries, another source of revenue is from Arogya a health plan for employees of small businesses in the locality. The members of “arogya plan” can avail free consultation and discounts on medicines and special services. Vaatsalya anticipates more revenues from preventive health plans in the future.

5.1.7 Social Impact

With a very humble beginning of one hospital in 2005 with 20 beds, today Vaatsalya has 17 Multi-specialty Hospitals spread across Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. Total bed strength today is around 1,200 plus, including 100 bedded MICU, 120 NICU beds, and 90 SICU beds with 1,500 plus well-trained and motivated employees. They serve around 1,30,000 patients/month on OPD basis and 5,000 patients/month on IPD basis.

The trust that the local population have in Vaatsalya has increased the repeat rate of the clientele for other health programmes. The medical cost to the patients has reduced to a very large extent as their travel cost to far off places where such medical treatment was earlier available and due to early intervention and preventive care. The most significant contribution of Vaatsalya has been in the treatment and counselling of 300 children with cerebral palsy. So far no such was treatment was available to these children.

‘Arogya’ programme that is offered as employee health plans to small business with less than 20 employees, has not only gained popularity in the local areas in reducing the cost of medical expenses but has generated good revenue to Vaatsalya. The firm expects to generate revenues of around INR 350 million by the end of this year and currently employs 1,200 people.

5.1.8 Sustainability and Business Model

Vaatsalya has been able to scale quickly since its inception and there is still a large untapped market. The entire business model is built on low-cost and no-frills hospital in the suburbs, the location of the hospitals close to medical colleges where there is availability of support services like diagnostic lab, blood bank, etc. are major determining factor. More often even availability of good medical practitioners and their willing to relocate is also significant factors. Different strategies are adopted to engage local medical practitioners, some of them provide the first level of contact for the patients who then refer the patients to the nearest Vaatsalya hospitals for further treatment; some good local practitioners also offer part-time consultations for specialisations.

Building the hospital from scratch, acquiring an existing hospital, or even tying up with government hospitals are the ways to expand and reach out to more beneficiaries. The cost of operation is kept as low as possible. To extend its benefits to below poverty line citizens Vaatsalya is considering partnering with microhealth insurance organisations, influencing with the government for the implementation of national health insurance schemes.

5.1.9 Challenges and Future Plans

Vaatsalya, over the years have been able to reduce the price of its services significantly due to deploying resources optimally and by reducing their operational and capital expenses. However, the basic challenge remains the same. Its prices are still unaffordable to poorest of poor. They are also not able to penetrate to remote villages as the number of people residing in these locations is very small making it unviable for sustained operations. Vaatsalya hospitals are currently located in areas with at least 100,000 population as they also depend on other services like blood banks and diagnostic centres. Another key challenge is availability of qualified doctors in these locations which act as a major hindrance to their growth.

They have an ambitious goal of bringing health care benefits to 2.5 million direct beneficiaries and another 10 million indirect beneficiaries through a network of 100 hospitals. They face three challenges to reach this goal: extending their portfolio of services, going to interior villages and reaching out to the bottom 30 % of the poor. Vaatsalya is now expanding its network into Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu. Regarding Vaatsalya’s potential, Ashwin states that “from our analysis, there is an opportunity for about 500 Vaatsalya hospitals India-wide”.

While expanding the number of services in their portfolio, they have to make sure that such services are affordable to the poor patients. For example, Vaatsalya team has realised that many of their patients travel kilometres twice a month for dialysis, and hence they set-up facilities for this service in a few of their hospitals.

“Dialyses equipments are expensive to set up. A reverse osmosis plant for four dialysis beds costs INR 6,00,000. Vaatsalya charges INR 900 per dialysis of which INR 450 is spent on reagents and equipment allocation costs, while INR 450 accounts for operational costs. Sometimes Vaatsalya needs to buy water worth INR 5,000 per day because they operate in some of the very arid zones of Karnataka where water supply is scarce” Says Ashwin Naik.

Vaatsalya also launched programmes on preventive health care for economically poor who cannot afford their services. They are also on the way to raise more funds from charitable trusts and raise additional revenues by renting out space for brands to advertise.

5.2 Case Study: 4 Jayashree Industries

Founder: A Muruganantham

(Website: www.newinventions.in)

5.2.1 Entrepreneurial Story

Muruganantham Arunachalam, founder of Jayashree Industries, hails from a poor rural family is a high school dropout and worked as a helper in a welding workshop. He set out with very clear vision to find a solution to get rural women access to health and hygiene during their menstrual periods. He found that his wife, just like many other women in rural areas was still using cloth during their menstrual periods which is highly unhygienic. He also understood that the branded sanitary napkins were prohibitively expensive and kept the rural women away from using them and a solution for this had to be found!

It took him four years of painful and embarrassing study to design a sanitary napkin making machine which can produce napkins at low cost. The cost of the machines used by the MNCs for the production of sanitary napkins is for INR 35 million; the cost of the automatic machine innovated by Muruganantham costs just about INR 75,000. He and his wife relentlessly made all efforts to get the local women to buy the napkins which were produced using low-cost indigenous method. The initial response to his product was very poor; but in a period of 3 years, he was able to sell more than 250 units of sanitary napkin making machine in 18 states.

5.2.2 Vision and Mission of the Social Venture

Jayashree industries aim to improve the living standards of rural women through innovation ; alleviate problem of livelihoods for most vulnerable sections of society and achieve the goal of promoting health of rural and poor women (Maternal health).

5.2.3 Value Proposition

Muruganantham with his limited knowledge but unlimited passion invented an indigenous and low-cost sanitary napkin making machine that operates on a small scale. In this machine, wood fibre (raw material) is defibrated, which forms the core and it is sealed with soft touch sensitive heat control, giving the final shape of the napkins. The machine requires single-phase electricity and 1HP drive can be accommodated in a space of 3.5 m × 3.5 m and will produce 2 napkins/min. It requires four persons to produce two pads per minute. The cost per sanitary pad produced by this machine is approximately INR1 to INR 1.50.

The semi-automatic mini sanitary napkin making assembly deploys four stages to produce the finished sanitary napkins. The main raw materials used for making sanitary napkin in this machine include wood fibre; thermo bonded non-woven, polyethylene—barrier film, release paper, super bond paste and LLDPE 50 GSM—packing cover.

5.2.4 Target Market

A large number of women, though they are aware, are not using sanitary napkins due to affordability.Footnote 7 Muruganantham sells his machine through Women Self-Help Groups (SHGs), who in turn manufacture the napkins using the machine and market the napkins to reach out to these underprivileged women, in the respective local areas. This according to him was the best way to reach quality sanitary napkins at affordable price among rural and lower middle class women who can switchover to more hygienic ways during their menstrual periods. For the SHGs, running a successful business like this is suitable, as the investment is nominal, the consumer market is growing and the price is affordable.

5.2.5 Infrastructure and Partner Network

This social entrepreneur has created a product that can be easily and efficiently run by the stakeholders at the grassroots (women from low income group and rural area) to earn a livelihood for themselves and produce and deliver sanitary napkin to poor women at affordable rates. This is done by low-cost production method, without compromising on the raw material used, and by reducing the people in the supply chain, right from its inception to reaching to the consumer. All the machines are operated only by the poorest women in the villages ensuring optimal use of the microcredit generated by a community.

5.2.6 Revenue Model and Cost Structure

Muruganantham supplies these machines only to poor women or a self-help group or to women in rural areas. He also supplies the raw materials for these machines and trains them to operate the machine.

When he initially started selling the machines it was sold as low as INR 47,000 but with inflation and increase in cost of raw materials, the price has gone up to INR 80,000, including 12.5 % tax. The machine cost along with raw material would cost INR 1,50,000. From each machine, one can make 1,000 pieces a day and a minimum of 25,000 pieces a month. In most places, the SHGs arrange for bank loans.

5.2.7 Social Impact of the Venture

Jayashree Industries has supplied more than 2,000 machines till the end of 2014, spread across 887 taluks in India and also 14 countries including Nepal, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Philippines, Mauritius, South Africa, Zambia, Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, Malawi, Somalia and USA. Every unit creates direct livelihood for 10 to 14 women. The marketing activities further creates indirect livelihood for the “Resident dealer” who generally are elderly women in villages and slums. The production on an average is about 1,000 units of pads per day. More than 867 local brands of sanitary pads are manufactured by these 2,000 units, generating a cumulative business volume of USD 100 million. Further, Over 9 million women are first time user of hygienic product during menstruation (Table 13.4).

5.2.8 Sustainability and Business Model

With innovation , and its dissemination through SHGs, rural women have been provided with direct and indirect employment and health consciousness. The total unit costs INR 80,000 and the cost of the final product works out to be INR 1/pad. NIF had supported the innovation with its Micro Venture Innovation Fund.

It has created viable employment opportunities by establishing production unit in villages including tribal women in remote places like Navapara village, Pali, where women had no access to health centres and had never used a napkin in their life.

5.2.9 The Challenges and the Future

While the enterprise has done fairly well in partnering with existing local women’s networks, the key challenge for Muruganantham is to identify the right partner in the ecosystem to replicate/scale this initiative globally. Mobilising resources through government subsidy or microfinance or bank loan for women to bear installation cost is yet another challenge apart from training local group in spreading awareness of health and hygiene along with training to operate this low-cost technology innovation . This will not only enable poor women to get access to affordable hygienic sanitary pads, but generate income for a sustainable livelihood by participating in the entire lifecycle as manufacturers, marketers and users of the product.

6 Comparative Study of Multiple Cases of Social Entrepreneurs

It is evident that each of the four social entrepreneurs are successful in impacting many underprivileged lives and work relentlessly to bring positive changes in their lives. EnAble India and Dream A Dream are registered as trust , while Vaatsalya is a private limited company and Jayashree Industries is a sole proprietorship venture. Vaatsalya has been able to raise several rounds of venture funding; while Enable India and Dream A Dream depend on grants, donations and event sponsorship; Muruganantham of Jayashree Industries relies solely on revenue earned from sale of his machines. Jayashree industries and Vaatsalya Hospitals, both working in health sector are able to reach lakhs of people through their products are services indirectly.

6.1 Business Model s—An Analysis—Based on Osterwalder ’ Improvement Process

By comparing these four social entrepreneurs through a common set of business model parameters using Osterwalder’s improvement process, we attempt to throw deeper insights on identifying the gaps and loopholes in their existing models, which in turn can help them to create successful, profitable and sustainable social enterprises (Tables 13.5, 13.6, 13.7, 13.8 and 13.9).

Major building blocks of social ventures’ business models irrespective of whether they are for profit or not for profit are,

-

Value proposition : Of the case studies discussed here, two of them are in the health sector and the other two are in empowerment through education and training . Vaatsalya operates low-cost hospitals in the rural and semi-rural areas, whereas Jayashree Industries concentrates on women health and hygiene, by manufacturing indigenous napkin making machines. EnAble India works in empowering the disabled by creating training contents and creating employment opportunities for them; Dream A Dream provides life skilled based education for vulnerable children. Each one of these social entrepreneurs is successful in creating a social value. They are passionate and clear about the value propositions and highly sensitive towards bringing in positive changes in the lives of their target audience.

-

Target market : The ecosystem in which these social entrepreneurs work is highly integrated and complex. On one hand they have the beneficiaries for whom social values are being created and on the other hand they have to raise funds for reaching out to the beneficiaries. This is very typical for most of the social enterprises. Enable India and Dream A Dream fall in this category and serve primarily PWDs and underprivileged children respectively. Both of them are being funded by individuals and corporate donors. Getting direct beneficiaries for their programmes is done efficiently by Dream A Dream, as they partner with NGOs which house these children or have access to these children. EnAble India have a much higher task of convincing unwilling parent of the disabled individuals.

Jayashree Industries sell the sanitary napkin making machines to SHGs that would directly benefit from manufacturing and selling the sanitary napkin to rural women, thereby creating micro entrepreneurs. Vaatsalya Hospitals reach out to rural and semi-urban Indians for primary and secondary health care. Funding partners are enthusiastic of investing in this venture due to its low-cost operating model.

-

Infrastructure and partnership: For successful operations, these social entrepreneurs currently work with a complex set of independent stakeholders like NGOs , corporates, individual volunteers , donors, venture capitalists, angel investors, service partners and many more. Dream A Dream signed MoUs with a few service partners in the field of sports and arts and NGOs to source the children. EnAble India also have tied up with NGOs which work with disabled persons. Vaatsalya needs high-quality doctors to relocate to tier 2 and tier 3 cities and initial capital to build the required hospital infrastructure . They also partner with small businesses to provide employee health plans. Muruganantham of Jayashree Industries avail manufacturing facilities from local factories and employs temporary labourers and pay them on piece rate basis. The social enterprises like Vaatsalya who shy away from Government subsidies may look again at them to bring in greater profitability .

-

Finance—Cost and revenue model s: Social enterprises need to make profit to bring in greater social impact . This can be achieved only though professionally managing and reducing the costs involved in developing the products and services on one hand and on the other, exploring multiple revenue models as done by Vaatsalya. Of the four cases, Dream A Dream is highly successful in creating surplus. They have excelled in creating the trust of donors to get funding on a recurring basis. They are also able to inspire students and young volunteers to help in running programmes which keeps the costs at bay. EnAble India too is successful in attracting donations from the same donors for the last 5 years. Vaatsalya has a high investment model to set up hospitals and pay the doctors attractive salary. Each of the hospitals, break-even in 24 months’ time frame. Nominal revenue is generated from consultations, surgeries and diagnostics and a membership fee is charged from local small businesses to provide employee health plans. Jayashree Industries work on a low-cost manufacturing model and sell the machines at very low margins.

7 Social Impact Measurement of the Ventures

An attempt is made to explore various growth indicators for each of these four ventures. Social impact is measured in both qualitative and quantitative terms. The qualitative growth indicators are directed towards the improvements of living conditions and basic amenities of underprivileged rural poor, many anecdotes and individual testimonials are proof of this which are not covered in this study. The focus here is to measure the quantitative impact of these ventures over a specific time period (Mostly last 3 years).

Some of these parameters are:

-

1.

Increase in number of direct and indirect beneficiaries

-

2.

Increase in number of units sold

-

3.

Increase in number of villages/towns covered

-

4.

Increase in the number of volunteers and employees

-

5.

Increase in the number of partners and collaborators

-

6.

Increase in the amount of funds raised

-

7.

Increase in the surplus created etc.

All the four social ventures have done significantly well on the basis of the above assessments. EnAble India, Dream A Dream and Jayashree industries have recorded an increase in the number of direct and indirect beneficiaries. Vaatsalya, in a span of 6 years has grown to 17 hospitals. Dream A Dream have doubled their volunteers in the last three years. (From 700 to 1,400). They also have successfully raised 23.7 million INR in 2012–2013 from 4.4 million in 2008. Vaatsalya has three venture funds invested in them.

Although the numbers look very encouraging, these social entrepreneurs nurture ambitious growth plans. EnAble India wants to train at least 2,000 PWDs per year and employ them in major companies. They also want to work with Government to bring in policy changes for employing the disabled. Vaatsalya wants their services to penetrate to lowest 30 % of population at the BOP and expand their network in the next 3 years to bring direct health care benefits to 2.5 million direct beneficiaries through 100 hospitals. Dream A Dream is preparing to scale up the programme to reach out to 2,40,000 children in 2015. Muruganantham wishes to supply 20,000 machines and create employment for one million women.

8 Conceptual Model of Social Enterprises

This study points to key sustainable elements in a business model for a social enterprise, like that of a commercial venture (Fig. 13.1).

What these case studies and many other social entrepreneurial initiatives all over the globe have in common is that they challenge the status quo and our conventional thinking about what is feasible. These inspired entrepreneurs, independent-minded, self-driven, and goal focused persons with strong human values, have shown us new paths and solutions, with a strategic outlook in finding the right value proposition for the underprivileged, by building the business model and participating in value creation and delivery. The social outcome will be to reach out to more beneficiaries and creating surplus. This is the direction we’re headed—towards a new model of creating social change!

Notes

- 1.

Ashoka India Foundation (AIF) is a leading international development organisation with the mission of accelerating social and economic change in India (Website: www.ashoka.org).

- 2.

Widely regarded as “Father of Social Entrepreneurship”.

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

- 6.

Economic Times June 13, 2011.

- 7.

Currently the size of the Indian Sanitary Napkins market is 2,000 Crores it is growing 16 % annually.

References

Alter K (2010) The four lenses strategic framework: towards an integrated social enterprise methodology. Virtue Ventures LLC—2010. http://www.4lenses.org

Braunerhjelm P, Stuart Hamilton U (2012). Social entrepreneurship–a survey of current research. Swedish entrepreneurship forum working papers (2012: 9)

Dees JG (1998) The meaning of social entrepreneurship. Comments and suggestions contributed from the social entrepreneurship funders working group, 6 pp

Department of Trade and Industry, UK (2012) Social enterprise, strategy for success

Drucker PF (1985) The discipline of innovation. Harvard Bus Rev 63(3):67

Harding R (2004) Social enterprise: The new economic engine? Bus Strateg Rev 15(4):39–43

Mair J, Marti I (2006) Social entrepreneurship research: a source of explanation, prediction, and delight. J World Bus 41(1):36–44

Morris M, Schindehutte M, Allen J (2005) The entrepreneur’s business model: toward a unified perspective. J Bus Res 58(6):726–735

Osterwalder A, Pigneur Y (2010) Business model generation: a handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. Wiley, Hoboken

Osterwalder A, Pigneur Y, Tucci CL (2005) Clarifying business models: origins, present, and future of the concept. Commun Assoc Inf Syst 16(1):1–25

Roberts D, Woods C (2005) Changing the world on a shoestring: the concept of social entrepreneurship. Univ Auckl Bus Rev 7(1):45–51

Schumpeter JA (1951). Essays: on entrepreneurs, innovations, business cycles, and the evolution of capitalism. Transaction Books, London

Seelos C, Mair J (2005) Social entrepreneurship: creating new business models to serve the poor. Bus Horiz 48(3):241–246

Shane S, Venkataraman S (2000) The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad Manag Rev 25(1):217–226

Stevenson HH (1983) A perspective on entrepreneurship. Harvard Business School, Boston

Stewart DW, Zhao Q (2000) Internet marketing, business models, and public policy. J Publ Policy Mark 19(2):287–296

Thompson JD, MacMillan IC (2010) Business models: creating new markets and societal wealth. Long Range Plan 43(2):291–307

Weill P, Vitale M (2002) What IT infrastructure capabilities are needed to implement e-business models. MIS Q Executive 1(1):17–34

Yin RK (2014) Case study research: design and methods. Sage publications, Thousand Oaks

Zott C, Amit R (2007) Business model design and the performance of entrepreneurial firms. Organ Sci 18(2):181–199

Zott C, Amit R (2010) Business model design: an activity system perspective. Long Range Plan 43(2):216–226

Websites

http://vaatsalya.com/2009/. Accessed on 9th April 2013

http://www.4lenses.org/setypology/intro. Accessed on 13th April 2013

http://www.ashoka.org/country/india. Accessed on 20th April 2013

http://www.ashoka.org/fellows. Accessed on 16th May 2013

http://www.growinginclusivemarkets.org/media/cases/India_Vaatsalya_2011.pdf. Accessed on 23rd May 2013

http://www.pluggd.in/social-entrepreneurship-in-india-funds-profitable-sectors-297. Accessed on 24th June 2013

http://www.schwabfound.org/sf/SocialEntrepreneurs/index.htm. Accessed on 27th June 2013

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer India

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Abhi, S., Venugopal, V., Shastri, S. (2015). Social Entrepreneurship—Building Sustainability Through Business Models and Measurement of Social Impact. In: Manimala, M., Wasdani, K. (eds) Entrepreneurial Ecosystem. Springer, New Delhi. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-81-322-2086-2_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-81-322-2086-2_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New Delhi

Print ISBN: 978-81-322-2085-5

Online ISBN: 978-81-322-2086-2

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsBusiness and Management (R0)