Abstract

Global imbalances, which culminated in the wake of the Great Recession, have been one of the most complex macroeconomic issues facing economists and policy makers. They have reflected differences in a number of factors in many countries, including saving, investment, and portfolio decisions. The cross-country differences in saving patterns, investment patterns, and portfolio choices can be “good”—a natural reflection of differences in levels of development, demographic patterns, and other underlying economic fundamentals. However, they can also be “bad”, reflecting distortions and risks at the national and the international level.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Global Imbalances

- Investment Patterns

- Major Advanced Economies

- Cyclically Adjusted Primary Balance (CAPB)

- External Imbalances

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Global imbalances, which culminated in the wake of the Great Recession, have been one of the most complex macroeconomic issues facing economists and policy makers. They have reflected differences in a number of factors in many countries, including saving, investment, and portfolio decisions. The cross-country differences in saving patterns , investment patterns, and portfolio choices can be “good”—a natural reflection of differences in levels of development, demographic patterns, and other underlying economic fundamentals. However, they can also be “bad”, reflecting distortions and risks at the national and international level.

To understand the nature of large imbalances, their root causes, and impediments to adjustment that may undermine growth, IMF undertook an in-depth assessment of global imbalances in the context of the G20 Mutual Assessment Process (MAP).Footnote 1 The Sustainability Report identified seven systemic members (China, France, Germany , India, Japan, the UK , and the USA) as having “moderate” or “large” imbalances that warranted more in-depth analysis. Sustainability assessments indicated that global imbalances have been driven primarily by saving imbalances—generally too low in advanced deficit economies and too high in emerging surplus economies—owing to a combination of equilibrium factors (demographic patterns), structural weaknesses, and domestic distortions . The assessments further suggested that corrective steps, including through collaborative action, aimed at addressing structural impediments and underlying distortions, would be needed to better support G20 growth objectives.

1 Imbalances—Conceptual Issues

A framework approach of “internal and external balance” provides a sound analytical foundation for analyzing global imbalances. The framework is well suited toward identifying, assessing, and addressing “large and persistent” imbalances in key dimensions that could jeopardize G20 growth objectives. The key elements include notions of external and internal balance, which are grounded in the concepts of macroeconomic equilibrium over the medium term (see Blanchard and Milesi-Ferretti 2009, 2011 for further discussion).

The framework allows us to study the linkages between internal and external imbalances . The current account reflects the excess or shortfall of national saving over investment, and, thus, connects external and internal imbalances. Moreover, viewing current accounts through the prism of saving–investment balances provides a good sense of various interlinkages and the levers for adjustment. The analysis of internal imbalances focuses primarily on public finances—cyclically adjusted primary balances (CAPBs) and public debt—since large fiscal imbalances are likely to bear upon external imbalances, can stifle growth, and can heighten vulnerability to market financing pressures . The examination of external imbalances focuses primarily on the current account—a core component of the balance of payments, which provides a concise summary of a country’s net external position.

Imbalances are not prima facie “bad” and warrant remedial action only to the extent that they are underpinned by distortions.Footnote 2 In particular, imbalances may reflect differences in saving and investment patterns and portfolio choices across countries, owing to differences in levels of development, demographic patterns, and other underlying economic fundamentals . Imbalances can be beneficial if they reflect the optimal allocation of capital across time and space. For instance, to meet its life-cycle needs, a country with an aging population relative to its trading partner may choose to save and run current account surpluses in anticipation of the dissaving that will occur when the workforce shrinks . Similarly, a country with attractive investment opportunities may wish to finance part of its investment through foreign saving and thus run a current account deficit. Such imbalances are not a reason for concern.

At the same time, however, imbalances may also reflect policy distortions, market failures, and externalities at the level of individual economies or at a global level. Imbalances can be detrimental if they reflect structural shortcomings, policy distortions, or market failures. For instance, large current account surpluses may reflect high national saving unrelated to the life-cycle needs of a country but instead that related to structural shortcomings, such as a lack of social insurance or poor governance of firms that allows them to retain excessive earnings . Similarly, countries could be running large current account deficits because of low private saving, owing to asset-price booms that are being fueled or accommodated by policy distortions in the financial system that impede markets from equilibrating.

Imbalances could also reflect systemic distortions, reflected, for instance, in the rapid accumulation of reserves by some countries to maintain an undervalued exchange rate. Such imbalances are a cause of concern, since they could undermine the strength and the sustainability of growth .

2 Explaining Imbalances

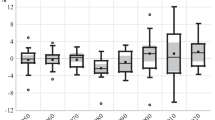

The sources of external imbalances in the run up to the crisis vary significantly across the seven economies, largely reflecting factors that have led domestic saving to differ widely . Current account deficits before the crisis have reflected low public and private saving in key advanced deficit economies, or low public saving, which has been partly offset by high private saving . Surpluses, on the other hand, have reflected high national saving in key emerging surplus economies, owing, in particular, to exceptionally high private saving that exceeds high private investment, or positive private saving–investment balances in key advanced surplus economies, due to high saving and low investment, which has offset high (modest) public dissaving in some cases .

A variety of structural and equilibrium factors have driven public saving behavior. Fiscal deficits have been underpinned by several forces, specifically : (i) persistently low growth, reflecting a decline in productivity, a shrinking labor force, and low investment (Japan); (ii) structural imbalances between tax revenues and spending commitments pre-crisis, including underfunded entitlement obligations (France, the UK, and the USA); (iii) the lack of fiscal rules and strict enforcement mechanisms to impose sufficient budgetary discipline; (iv) political economy considerations exerting strong pressure on spending and resistance to raising taxes (India, Japan, and the USA); and (v) financial repression in some emerging economies .

However, domestic policy distortions (defined broadly as factors that impede a market from equilibrating) have also played an important role in driving imbalances.

Distortions in financial systems in key advanced economies have fueled low private saving and large current account deficits . The distortions, pertaining to regulatory and supervisory frameworks, were partly responsible for a fundamental breakdown in market discipline and mispricing of risk (reflected in credit and housing booms) and contributed to a widening of external imbalances in major advanced deficit economies, notably the USA and UK . Weak private saving–investment imbalances before the crisis have played a role in fueling current account deficits in major advanced economies.

The high national saving in China reflects significant underlying distortions . Policy distortions or gaps—inadequate social-safety nets, restrictive financial conditions, an undervalued exchange rate , subsidized factor costs, limited dividends, and lack of competition in product markets—have underpinned exceptionally high national saving and, in turn, current account surpluses . Large current account and balance of payment surpluses have, in turn, led to massive reserve accumulation in China (and elsewhere), contributing to the low-cost financing of US current account deficits .

Weak investment in advanced surpluses economies also reflects policy distortions (Japan and Germany) . Specifically, favorable private saving–investment balances reflect, in part, either distortions that keep private investment growth weak, while corporate savings are large, or distortions in the financial sector may be a drag on domestic investment. Distortions have also played a role in fueling public dissaving in some emerging deficit economies (India), where tight financial restrictions have allowed the perpetuation of large fiscal deficits .

3 Concluding Remarks

Global imbalances have narrowed markedly, as global trade and activity have slowed down. Most of the adjustment took place during the Great Recession of 2008–2009, when global growth was negative. The narrowing of global imbalances mainly reflects weaker domestic demand in external-deficit economies rather than stronger demand from external-surplus economies. However, healthier adjustments have also taken place: fiscal balances in external-deficit economies have improved, while domestic demand in China has been strong and oil exporters have increased their social spending, bringing down their large surpluses.

Additional decisive action by policy makers is needed to durably reduce global imbalances and the associated vulnerabilities. It must be emphasized that the policies that would most effectively lower global imbalances and related vulnerabilities are very much in the national interests of the countries concerned, even when considered purely from a domestic viewpoint. Many external-deficit economies need strong medium-term fiscal adjustment programs. The policy priorities for emerging market economies with external surpluses and undervalued currencies are to cut back official reserve accumulation, adopt more market-determined exchange systems, and implement structural reforms, for example, to broaden the social safety net .

Broadly speaking, sustainability assessments indicate that imbalances have been driven primarily by saving imbalances . Specifically, saving in major advanced economies has been too low, while it has been too high in key emerging surplus economies. This, in turn, implies that policy makers need to continue their efforts to further promote the dual rebalancing acts—a shift from public to private demand led growth in major advanced economies and a shift from growth led by domestic demand in major advanced deficit economies toward external demand and vice versa in major emerging surplus economies.

Accordingly, country-specific policies are needed to address underlying distortions to facilitate the dual rebalancing acts. Such policies will also help anchor the shared G20 growth objectives of strong, sustainable, and balanced growth. In particular, fiscal consolidation that is appropriately timed and paced is needed across major advanced economies to reduce persistent deficits, create policy space, and anchor sustainability . Fiscal consolidation will, however, depress growth in the near term. Hence, closing the output gap will require complementary policies. In addition, growth in these countries will need to be fueled by higher net exports. To offset weaker demand in major advanced countries, internal demand will need to increase elsewhere, notably the surplus countries, to support domestic and global growth. This will require lower national saving in key emerging surplus economies, notably by reducing the distortions that have kept saving exceptionally high. There is also room to bolster domestic demand by reducing private saving–investment balances in advanced surplus economies, notably by lowering corporate saving and boosting investment by reducing distortions.

Notes

- 1.

The result from the analysis was published in a 2011 Sustainability Report—see for details: https://www.imf.org/external/np/g20/map2011.htm.

- 2.

For further discussion see: Blanchard and Milesi-Ferretti 2009, “Global Imbalances: In Midstream?,” IMF Staff Position Note 09/29 (www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/spn/2009/spn0929.pdf).

References

Blanchard O, Milesi-Ferretti G-M (2009) Global imbalances: in midstream? In: O Blanchard, I SaKong (eds) Reconstructing the world economy. International Monetary Fund, Washington

Blanchard O, Milesi-Ferretti G-M (2011) (Why) should current account balances be reduced? IMF Staff Discussion Note 11/03. International Monetary Fund, Washington

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer India

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Stavrev, E. (2014). Global Imbalances: Causes and Policies to Address Them. In: Callaghan, M., Ghate, C., Pickford, S., Rathinam, F. (eds) Global Cooperation Among G20 Countries. Springer, New Delhi. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-81-322-1659-9_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-81-322-1659-9_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New Delhi

Print ISBN: 978-81-322-1658-2

Online ISBN: 978-81-322-1659-9

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsEconomics and Finance (R0)