Abstract

This chapter offers a blueprint for the integration of financial, environmental, social, and governance reporting, an emerging practice that has profoundly changed the way organisations develop strategic plans, approach decision-making, measure success, and manage risks in the twenty-first century. Overlooked in the act to prepare a traditional balance sheet are the 80 % of a company’s assets and liabilities, including social and environmental, that conveniently fall outside the scope of modern accounting. In this chapter, we ask the question, why have we continued to take an “unbalanced” approach? We envision a future when a balanced sheet, renamed the value statement, captures the financial, social, and environmental conditions of a firm over multiple periods of time and this information is further supported by a statement of change in stakeholder’s equity (rather than stockholders’ equity). By quantifying assets, liabilities, and performance related to all forms of capital, businesses worldwide are leveraging Integrated Bottom Line (the analysis and disclosure of financial, social, and environmental assets and liabilities to internal, and external stakeholders of a firm) to achieve long-term value creation, innovation, and competitive advantage. IBL goes beyond an accounting practice to become a catalyst for sustainable management solutions, risk management, and stakeholder engagement. To help demonstrate this transformation of performance measurement, the information within this chapter reviews the evolution of integrated reporting, the need for more involvement from accountants to go beyond a myopic focus on the bottom line to enabling shared value through evidence based management, and a review of enabling organisations. The chapter concludes with a call to action for business schools and business organisations to work together at the intersection of integrated reporting to develop solutions for tomorrow’s measurement problems.

To get all businesses involved in solving the world’s toughest problems, we must change the accounting rules.

Peter Bakker, President of the World Business Council on Sustainable Development, at the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, Rio + 20, 2012

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Corporate Governance

- Balance Sheet

- Pilot Programme

- Global Reporting Initiative

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Chapter Objectives

Wrapped in the context of sustainability, a global imperative, this chapter offers a blueprint for the integration of financial, environmental, social, and governance reporting, an emerging practice that has profoundly changed the way organisations develop strategic plans, approach decision-making, measure success, and manage risks in the twenty-first century. By quantifying assets, liabilities, and performance related to all forms of capital, businesses worldwide are leveraging Integrated Bottom Line (IBL) reporting to achieve long-term value creation, innovation, and competitive advantage.

Contemporary businesses operate in a complex system of global commerce that connects an ever-expanding array of sellers with customers for products and services. Publics and governments, employees and consumers are powerful forces in these modern value chains. A diverse and growing number of stakeholders demand transparent reporting about the varied activities of a company and its suppliers, distributors, and customers, including the social and environmental impacts of products and services throughout their lifecycles.

After reading this chapter, you will understand why IBL is a fundamental tenet of sustainable enterprise management and a growing priority for organisations of all kinds. In addition, you will discover the extent to which disclosure of performance beyond quarterly profits has evolved since the turn of the twenty-first century. Specifically, you will gain insight to:

-

1.

The limitations of traditional financial reporting practices and standards for assessing the health of a firm;

-

2.

How assets and risks associated with natural, manufactured, social, and informational capital affect a firm’s valuation;

-

3.

Emerging trends in financial, environmental, social, and governance reporting;

-

4.

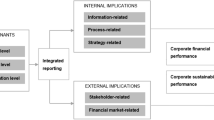

Internal and external drivers for adopting Integrated Bottom Line reporting;

-

5.

Benefits of integrated analysis and reporting for internal and external stakeholders;

-

6.

Obstacles to implementation of integrated reporting.

2 Introduction

Reconciliation of revenues versus costs is as old as commerce itself. Throughout history, merchants and service providers have translated transactional data into financial summary information for taxing authorities, financial backers, and the general public. As organisations grew larger and more complex, preparing and interpreting financial statements required more expertise and higher education assumed the role of preparing accountants and analysts. Nevertheless, the basic approach to reporting remains unaltered; standard financial reports focus on capturing a company’s status at a single point in time. Despite an explosion in sustainability reporting and ever-advancing computing technologies, the accounting discipline has been slow to adopt the data analysis techniques and comprehensive reporting practices that inform today’s corporate decisions and investor choices in a global economy.

The Triple Bottom Line (TBL), a concept that integrates financial, social, and environmental performance measurements (Elkington 1994), prompted a significant shift in management thinking, although it was not embraced by the accounting profession. A TBL reporting approach helps organisations organise a vast amount of internal and incoming information across a wider range of risks and opportunities. When corporate performance is evaluated against a Triple Bottom Line, an organisation can spot economic, social, and environmental issues before they become crises (Savitz and Weber 2006). Unfortunately, TBL reporting does not go far enough. Many firms and industries are already operating in or approaching crisis mode. When liabilities arise from natural disasters or unintended consequences of industrial processes, it is too late for risk management measures.

If sustainability is the responsible utilisation of all resources, and accounting is the universal language for comparing worth from company to company, then it should come as no surprise that integrated reporting has emerged as the next revolution for managing performance, raising capital, and leveraging innovation.

For the purposes of this chapter, an Integrated Bottom Line (IBL) is defined as analysis and disclosure of financial, social, and environmental assets and liabilities to the internal and external stakeholders of a firm. This definition takes IBL beyond an accounting practice to a catalyst for sustainable management solutions, risk management, and stakeholder engagement.

The formal and informal systems required for IBL reporting already exist in processes for reporting financial, human resource, sustainability and corporate social responsibility activities. However, many businesses struggle to quantify the intangible assets and liabilities that affect profitability and liquidity, even though intangibles account for up to 80 % of a typical company’s valuation (Barry 2013, p. 7). The missing link to sustainable management solutions for many in business is the ability to fully understand natural and human capital and monetise the firm’s impacts on the environment and society. The result is that a financially-at-risk company can appear to be highly profitable on paper if the environmental and social assets and liabilities have not been assessed and reported accurately (Fig. 13.1).

This chapter takes a theoretical and practical look at the intersection of accounting, management systems and sustainability and challenges businesses (and business schools) to reassess the balance sheet by exploring the potential for Integrated Bottom Line reporting and analysis. Our goal is to provide evidence of an emerging paradigm and prepare managers to assess the true value of a firm for a new era in transparent reporting.

3 Evolution of Integrated Bottom Line Reporting

It took little more than a decade for multi-national, Fortune 500 and mid-tier companies to adopt the practice of issuing regular Sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) reports. Consolidating financial, CSR, and sustainability information into a single report that presents a comprehensive and accurate picture of the firm’s true value is the next frontier for performance disclosure for companies of every size in every industry.

As far back as 2000, companies such as Novozymes began issuing integrated reports. A diverse group of firms from Europe, North America, Africa, Asia, and South America—including Novo Nordisk, Disco, Kumba Iron Ore, United Technologies, Natura, Philips, American Electric Power, PepsiCo, and Southwest Airlines—were among the pioneers in IBL reporting for their varied industries. In October 2011, the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) launched the Pilot Programme Business Network, engaging over 100 businesses from 37 countries in dialogue about developing and testing frameworks for integrated reporting (IIRC 2013). According to the National Association of Corporate Directors, over 80 of the world’s largest multi-national corporations—including Coca-Cola, HSBC, Microsoft, Volvo, and Unilever—were piloting integrated reporting in the first quarter of 2013, and Bayer announced intent to issue integrated reports in 2014.

Not surprisingly, banks are positioned to lead adoption of integrated reporting and capitalise on the risk management benefits of IBL analysis. In 2013, the banking sector represented nearly 10 % of the businesses in the Pilot Programme of the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC). Participating banks included: BBVA (Spain); BNDES and Itau Unibanco (Brazil); DBS Bank (Singapore); Deutsche Bank (Germany); HSBC (UK); Bankmecu and the National Australia Bank (Australia); and Vancity (Canada). Proactive reporting exemplars in the industry include the SBG or Standard Bank Group (South Africa). The SBG was highlighted by the IIRC for integration of information, risk identification, transparency in disclosing how it generates revenues, and projected impacts of market forces (Adams 2013) (Fig. 13.2).

Integrated Bottom Line Reporting Adoption Timeline. (Sources: Eccles, Robert and Daniela Saltzman. Achieving Sustainability Through Integrated Reporting. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Summer 2011. “Integrated Reporting.” GlobalReporting.org. Global Reporting Initiative, 7 May 2012. Web. 1 Nov. 2013)

Noticeably absent in the movement toward Integrated Bottom Line reporting has been leadership from the accounting profession.

3.1 The Myopic Focus on the Bottom Line?

While the formal practice of accounting emerged in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, it was the commercialisation of a reliable adding machine by William Burroughs in the 1880s that upgraded the repetitive, clerical tasks of bookkeeping to trade status and transformed accounting into a profession responsible for analysing and using financial information (Badua and Watkins 2011, pp. 76–77).

The American Institute of CPAs (AICPA), the world’s largest professional organisation for accountants, traces its origins to 1887. This association encompasses 394,000 members from 128 countries. AICPA sets U.S. auditing standards and develops and grades the Uniform CPA Examination. Through a joint venture with the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants, AICPA established the Chartered Global Management Accountant designation to elevate management accounting globally (American Institute of CPAs 2013). Although the chairman’s letter in the organisation’s 2012–2013 annual report includes a reference to integrated reporting as offering “a fuller picture of a business by mapping how an organisation’s strategy, governance, risks, performance and prospects lead to value” (American Institute of CPAs 2013), the association’s web site featured no navigation links to Integrated Bottom Line resources or publications that focused on IBL at the end of 2013, and a site search produced no publications or web-presented narrative on integrated reporting or association involvement in developing standards. Perhaps the accounting profession is hampered by allegiance to its own traditions, including methodologies for preparing basic financial reports (Fig. 13.3).

The four standard financial reports reflect a firm’s status at a single point in time. The balance sheet offers what is considered the most comprehensive snapshot of a company’s financial position. It presents assets = liabilities + shareholders’ (owners’) equity on a specific date. From a balance sheet, investors in publicly held companies can see exactly what the company owns and owes, as well as the amount invested by the shareholders, thus getting a snapshot of a company’s financial health at a given moment. The balance sheet must always balance; the left side, assets, is always equal to the right side, liabilities and shareholders’ equity.

Overlooked in this balancing act to prepare a proper balance sheet are the 80 % of a company’s assets and liabilities, including social and environmental, that conveniently fall outside the scope of modern accounting. So, why have we continued to take an unbalanced approach?

The reference to “bottom” describes the relative location of the net income figure on a company’s income statement, the financial report that captures profit or loss status, again at a single point in time. The net profit or loss figure will almost always be the last line at the bottom of the page—the point where all expenses have been subtracted from revenues. This stands in contrast to revenues, which are the “top line” figures on an income statement. To improve bottom line profits, companies focus on increasing revenue through growth and/or cutting costs through efficiencies.

By capturing a company’s financial health at a single point in time, without considering the full impacts and value created by a firm, the balance sheet and income statement reflect an incomplete and biased view of financial health and liquidity. McKinsey and Company have recently asked for change in the way the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) income statement is structured to help investors find the information they need for decision making in one place and in a format that is easy to understand and compare (Jagannath and Koller 2013). As such, these standard financial reports should be a transparent disclosure of a company’s revenues and expenses that investors can readily interpret. Not surprisingly, the call for measurement and reporting of sustainability practices that impact top and bottom lines is coming from a diverse group of stakeholders, including accounting firms, corporate executives, investment analysts, sustainability thought leaders, and business educators. The prevailing sentiment across stakeholders is that new performance measures should reside with known financial reporting mechanisms such as the income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow statements. We envision a time when a truly balanced sheet, perhaps renamed the value statement, captures the financial, social, and environmental conditions of a firm over multiple periods of time accompanied by a statement of change in stakeholder’s equity (rather than stockholders’ equity).

Which stakeholders should lead the way? As Paul Hawken once said, “Despite our management schools, thousands of books written about business, and despite multitudes of economists who tinker with the trim tabs of a world economy, […] our understanding of business—what makes for healthy commerce, what the role of such commerce should be within society—is stuck at a primitive level” (Hawken 1993, p. 1). We know that newly formed organisations, such as the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) and the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC), have already realised that a Triple Bottom Line approach does not remove the focus from costs. One stakeholder group—business schools—is poised at the crossroads of theory and practice where research and pedagogy collide to inform business leaders.

Companies and business schools have been working on new ways of measuring performance as evidenced by changing practices in corporate reporting and international recognition for MBA programmes that integrate aspects of sustainability in curricula, including alternative MBA rankings such as “Beyond Grey Pinstripes” by the Aspen Institute and “Green MBA” rankings from Corporate Knights. Lovins et al. 2010, Elkington and others suggest that adoption of a Triple Bottom Line framework by corporations and business schools has brought about greater awareness of environmental and social capital on the income statement, yet TBL reporting is neither complete nor accurate. In practice, the TBL approach tends to consider programmes that protect the planet and enhance people as expenses rather than assets, and this has led companies to a “bolted-on” or cost-centre-driven approach to sustainability. Such a cost-centred perspective blinds executives to significant business value that sustainability-orientated practices could contribute. In our own research, sustainability has emerged as the primary driver of innovation and competitive advantage at better-managed companies that focus on value creation, not cost-cutting (Sroufe et al. 2012).

Even the best managed companies cannot fully capture the value of sustainability on traditional income statements, balance sheets, and cash flow statements. These companies may be building social and environmental capital, but they lack a way to succinctly provide this information to their stakeholders. Companies in some industries cannot survive without monitoring and managing use of mission-critical natural resources. Some are required to report their conservation efforts and results; others voluntarily disclose such information in keeping with their industries’ norms. For example, Duquesne Light, a regional energy distribution company near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and H. J. Heinz, a multi-national food company, monitor, and manage energy and water usage. However, all companies use energy and water. Why are so few held accountable for ethical use and preservation of natural resources?

Business schools have an obligation to teach a new generation of leaders to measure and disclose performance, fully and accurately. Peter Bakker, President of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, offers context for this appeal: “We need to ensure that corporate reporting makes clear how a company is making its money, not just how much money it has made. For every robust measure of return on financial capital, we need an equally robust measure of return on natural capital—the supply of natural ecosystems that businesses turn into valuable goods or services—and yet another for social capital—the economic benefits that derive from intellectual capital and co-operation among groups” (Bakker 2012).

Encouragingly, in April 2013, Joanne Barry, publisher of The CPA Journal, urged CPAs to take part in the standards-setting process. In her appeal to the accounting profession, she defined integrated reporting as “presenting information to investors and other stakeholders about a company’s financial health, along with information about its environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) performance […] which […] make up as much as 80 % of market capitalisation” (Barry 2013, p. 7). We believe that active involvement of accounting professionals in the design of reporting standards for a new era will accelerate the adoption of IBL reporting and improve the integrity of methodologies for quantifying assets and liabilities based on all types of capital.

4 Creating Shared Value

Deloitte calls integrated reporting the most significant change in years with importance that extends beyond changing report formats: “Corporate reports—whose growing sophistication and range have been a reflection of the development of the global economy over the past two centuries—are in some sense the rulebook that investors and society at large use to ‘keep score.’ Change the rulebook and you will almost certainly change the game” (Main and Hespenheide 2013).

Shared value creation offers a different view of capitalism. In their 2011 Harvard Business Review article, Porter and Kramer call for reinventing capitalism by “reconceiving the intersection between society and corporate performance.” Capitalism, they maintain, is an unparalleled vehicle for meeting human needs, improving efficiency, creating jobs, and building wealth. Similarly, Avery Lovins has re-examined the role of commerce in society, observing that a narrow conception of capitalism has prevented business from harnessing its full potential to meet society’s broader challenges (Lovins 2011). “The purpose of the corporation,” Porter and Kramer suggest, “must be redefined as creating shared value, not just profit per se” (Porter and Kramer 2011, pp. 62–77). Some have claimed that a sustainable company manages its risks and maximises its opportunities by identifying key non-financial stakeholders and engaging them in matters of mutual interest (Savitz and Weber 2006). Others believe that we should ignore non-financial stakeholders and instead follow existing GAAP and Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) financial reporting protocols, arguing that change will come when the market is ready for it. To the contrary, we are already in the midst of a sea of change.

Already, Integrated Bottom Line Reporting has Achieved Worldwide Momentum.

The Grenelle II Act in France was passed in 2012, mandating extra-financial reporting (Institute RSE 2012). As of July 2013, 509 of the world’s leading business schools had become signatories of the Principles for Responsible Management Education (PRME), a United Nations’ Global Compact that defines six principles as a guiding framework for integrating corporate responsibility and sustainability in business education curricula, research, teaching methodologies, and institutional strategies. The International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC)—a global coalition of regulators, investors, accountants, companies, and non-government organisations—had active pilot programmes with 100 companies from across the world and 35 investment organisations in 2013 (IIRC 2013). In the United States, the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) was established to create sustainability standards across 88 industries in ten sectors to complement the standards of the (FASB) and provide context for comparative ESG reporting by 2015 (Accounting for a Sustainable Future 2013) (Figs. 13.4 and 13.5).

4.1 IBL as Enabler of Shared Value

The strategic advantages from integrating reporting and analysis of all forms of capital are many and varied. A paradigm shift from capturing an organisation’s worth at a single point in time to Integrated Bottom Line reporting offers enormous potential for improving decision support, performance management, and investment. The Integrated Bottom Line approach can and will provide more accurate analyses of business performance (Lovins 2006), informing strategic planning. IBL offers insight for designing and implementing sustainability programmes to engage stakeholders, inspire innovation, and differentiate products and services. Macro-level benefits include “greater market efficiency and lower volatility for the markets where integrated reporting is successfully delivered” (Hudson et al. 2012). The benefits of IBL have been examined in a wide range of publications (Main and Hespenheide 2013; Hudson et al. 2012; Lovins et al. 2010; Eccles and Armbrester 2011; Eccles and Krzus 2010; KPMG 2012) (Fig. 13.6).

Integrated Bottom Line reporting opens opportunities for improving every aspect of a company’s operation by enabling, clarifying, quantifying, valuing, improving, and integrating to achieve results:

-

Enabling

-

Enables decision makers to assess and manage risk more accurately

-

Enables managers to identify earnings related to sustainability practices

-

Enables users to connect key pieces of information for investment decision-making process

-

Enables simplification of internal and external reporting for consistency and efficiency

-

Enables business-critical information to be found easily

-

Enables strategy and transparency more effectively

-

-

Clarifying

-

Clarifies the ROI from innovation

-

Clarifies the ROI of sustainability initiatives more accurately

-

Clarifies the top, material issues impacting an organisation

-

-

Quantifying

-

Quantifies how sustainability metrics translate into productivity

-

Quantifies relationships between social and environmental initiatives and productivity

-

Quantifies relationships between environmental, social, governance, and financial performance

-

Quantifies how efficiency drives profitability

-

Quantifies relationships between material financial and non-financial performance metrics

-

-

Valuing

-

Values improving recruitment and lowering retention costs

-

Values long-term unquantifiable risks or opportunities

-

Values opportunities, and risks through a focus on longer-term business impacts

-

-

Improving

-

Improves performance reporting across markets

-

Improves access to capital

-

Improves decision makers’ ability to transform qualitative stories into quantitative data,

-

Improves compliance with regulations and corporate governance requirements

-

Improves stakeholder credibility through transparent and independently assured reporting

-

-

Integrating

-

Integrates sustainability into financial and management accounting

-

Integrates relevant ESG issues linked to the firm’s strategy and progress

-

Integrates material information on financial and non-financial performance in one place

-

Integrates thinking and management

-

4.2 Garnering Momentum for IBL

What will it take to turn this movement toward Integrated Bottom Line reporting into a global practice? Peter Bakker, president of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), raised eyebrows when he told attendees at the 2012 United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development in Rio (also known as Rio + 20) that “accountants will save the world!” He has called for all businesses to get involved in solving the world’s toughest problems by changing the accounting rules (Bakker 2012).

The WBCSD is a membership organisation consisting of over 200 companies worldwide, including the Big Four accounting firms. The organisation launched a programme on reporting and investment that will collaborate with The Prince’s Accounting for Sustainability Project(Prince’s Accounting 2013) and the IIRC to make sustainable performance concrete, measurable, comparable, and linked to scientific priorities. The focus is on both internal sustainability reporting for improved risk and performance management, as well as on external disclosure as a driver for more accurate valuation of companies and improved allocation of capital market investments. The WBCSD plans to convene a forum for CEOs and accountants to discuss and develop large-scale solutions for finance and reporting, and they are exploring the possibility of developing a world-class training programme for CFOs on sustainability.

If the world wants to address our many sustainability challenges—if business wants to restore society’s trust—business must be more transparent. IBL reporting acknowledges that the resources we exploit or conserve and the social benefits we engender or lose must be factored into a company’s value and thus into the day-to-day management. This is not a matter of incremental change, but a radical transformation. As Bakker proclaimed, accountants can save the world by modernising century-old practices. Information technology will be the enabler.

From a practical perspective, perhaps the best way for a company to benefit is to make a commitment to releasing an integrated report before IBL reporting becomes commonplace. By its very nature, an integrated report is a concise communication that reveals how a business’s strategy, performance, and governance lead to the creation of value over various intervals of time (Hickman and Tysiac 2013). Integrated reporting is beneficial in that it provides a “more cohesive and efficient approach to reporting, informs capital allocation decisions, enhances accountability and stewardship, and supports integrated thinking” (Hickman and Tysiac 2013).

According to the IIRC, an integrated report should meet uniform criteria. While leaders from industry, government, and academia, including practice experts from prominent accounting and consulting firms, offer input for what that criteria might be, Hickman and Tysiac (2013) have described some basic guiding principles for an integrated report (Fig. 13.7):

-

Strategic focus and future orientation

-

Connectivity of information

-

Stakeholder responsiveness

-

Materiality and conciseness

-

Reliability and completeness

-

Consistency and comparability

Integrated reports provide insight to a company’s inner workings and precise valuation for immaterial objects. Integrated Bottom Line reports expose all aspects of a company’s assets or liabilities, including finances, environmental effects, and human capital. Main and Hespenheide (2013), citing IIRC guidelines for a series of principles and content elements, show that these reports should include an organisational overview and business model, operating context including risks and opportunities, strategic objectives and strategies to achieve objectives, governance and remuneration, performance, and finally future outlook. Presenting a more complete picture of the health of a company will provide a more precise measurement of the company’s performance to its shareholders and the community at large. If the complete scope of a company’s performance and environmental/social effects are made available, consumers and investors will be enabled to make more informed decisions about their purchases of products or services. Another positive to this style of financial reporting is that an integrated report provides for more reliable comparisons to other businesses.

5 Integration Already in Motion

If you think reporting is not yet a big deal consider the following evidence: The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), Global Initiative for Sustainability Ratings (GISR), and the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) have combined efforts to create a collaborative framework for integrated reporting and the convergence of financial and Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) information. These organisations are now supported by the efforts of B Lab (the non-profit serving B Corporations), the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), and the Forum for the Futures Sustainable Business Model Group. Within the next few years, there is likely to be a unified set of material criteria to rate and rank a firm’s progress toward being a sustainable organisation relative to its peers.

Consider what is already happening in other regions of the global marketplace: The Hong Kong stock exchange is now making ESG disclosure a best practice. Integrated reporting is now mandatory by the Johannesburg Stock Exchange and the King III Code of Corporate Governance in South Africa as they now have one of the highest reporting ratios of carbon accounting and integrated reporting. With trends come leading and lagging companies. Next, we highlight some leading companies who have been indicators of the coming change in corporate reporting.

Innovative Companies Pushing the IBL Reporting Frontier

Some major businesses already prescribe to the Integrated Bottom Line accounting method. In fact, beginning in 2010, companies could not be listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange unless they provided some measure of their Integrated Bottom Line performance. Similarly, the Brazilian stock exchange (BM & FBovespa) encourages the companies on their list to disclose their sustainability reports, or explain why they don’t publish them. Integrated reporting is a trend gaining ground in Brazil after Robert G. Eccles and Michael P. Krzus published their book One Report and it was translated into Portuguese (Global Reporting Initiative 2012, p. 4). One company in particular stands out as a pioneer in the integrated reporting arena: Natura.

Natura is a Brazilian company that first published an integrated annual report in the year 2002 (Eccles and Serafeim 2013, p. 50). It was listed in Forbes as one of the top ten most innovative companies in 2011, and for good reason (Eccles and Serafeim 2013, p. 50). Natura launched 435 new products over a 3-year span (2009–2011), boasts a greater market share than Unilever or Avon, and from 2002–2011 grew its revenues by 463 % (Eccles and Serafeim 2013, p. 50). In addition, Natura’s average profit margin is 68 % as compared to the industry average of 40 % (Eccles and Serafeim 2013, p. 50).

At the same time, “Natura has significantly reduced its greenhouse gas emissions and water consumption, developed more environmentally friendly packaging, and provided training and education opportunities to about 560,000 consultants” (Eccles and Serafeim 2013, p. 50). This is a wonderful example of a company that has grown its businesses substantially while also being environmental and social stewards. Natura viewed integrated reporting as a great way to signal its commitment to and focus on environmental and social responsibility. Additionally, the company entwines management bonuses with reaching environmental and social goals (Eccles and Serafeim 2013, p. 50). Natura then took a leap into the future with the establishment of its sustainability social network, Natura Connecta.

Natura Connecta is a social networking site that allows members to participate in discussions about sustainability, environmental and social stewardship, and their expectations regarding sustainability in the future. Over 8000 people joined the site in its first year of operation (Eccles and Serafeim 2013, p. 50). The site had one very notable, distinctive feature: Natura Connecta members were invited to use the site to establish a WikiReport to establish and draw upon each other’s ideas regarding the main site topics (Eccles and Serafeim 2013, p. 50). Natura then used the wiki in its next annual integrated report.

This is one example of how a very successful, innovative company used integrated reporting to engage not only its stakeholders but also its shareholders. Employees were financially incentivised to make responsible decisions, consumers were engaged with the social network and wiki process, and other businesses and the communities at large were able to see an integrated report first hand.

Another business that is leading the way with integrated reporting is Danish pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk. Novo Nordisk first introduced the Integrated Bottom Line approach to its articles of association or bylaws in 2004 (Novo Nordisk 2013a). Novo Nordisk’s board of directors voted on the adding of the notion of environmental and social responsibility to their bylaws and turned this into a major focus for the company.

The company then decided to arrange a series of goals for various time intervals in order to hold itself accountable. Novo Nordisk has a 10 year, long-term strategy that is tied to the performance ranking of the executive management team. One example of a medium-term to long-term goal is the reduction of waste emissions as production increases (Novo Nordisk 2013a). Medium or long-term goals are broken into individual short-term goals that are then distributed across departments to individuals in the company. Breaking down the big goals into manageable chunks and assigning them to individuals to be used as performance goals is one way to make medium or long-term goals seem more manageable. It also increases individual accountability and participation.

Novo Nordisk emphasises doing business in a sustainable way because it believes that building trust within the community will ultimately protect its brand and attract the best and the brightest to work for the company (Novo Nordisk 2013b). There are a few ways Novo Nordisk strives to accomplish this. As previously mentioned, reduction or eradication of waste emission is an important long-term goal. Novo Nordisk also maintains a heavy focus on improving public health, which benefits patients as well as society and shareholders (Novo Nordisk 2013b).

The company shows a commitment to increasing the community’s lifespan, thereby having a pronounced effect on the social aspect of Integrated Bottom Line. Novo’s commitment to reversing the effect that its production has on waste emission is a contribution to the environmental category of Integrated Bottom Line. Its decision to tackle social and environmental issues displays the true intended nature of the Integrated Bottom Line approach. Novo’s policy to submit an annual integrated report—whether the results are good or bad—helps keep the company and management leaders accountable to shareholders and the community.

This disclosure fosters the close relationship that Novo Nordisk seeks with its stakeholders (namely individuals with diabetes) and further demonstrates that Novo Nordisk is an innovative, responsible company with its finger on the pulse of stakeholder needs (Novo Nordisk 2013b).

A company that is relatively new to the integrated reporting game but still a heavy hitter with a strong history is Coca-Cola Hellenic Bottling Company or Coca-Cola HBC.

Coca-Cola HBC is the parent company of the Coca-Cola Hellenic Group and the second-largest bottler of products of The Coca-Cola Company in terms of volume with sales of more than two billion unit cases. It has a broad geographic footprint with operations in 28 countries serving a population of approximately 581 million people (Coca-Cola HBC 2013).

The company first published a Global Reporting Initiative corporate sustainability report in 2003 and has continuously worked to improve its commitment to sustainability since that time (Coca-Cola HBC 2013).

Coca-Cola HBC took its commitment to the next level in 2012 and became a part of the International Integrated Reporting Council’s Pilot Programme. With the help of the IIRC, Coca-Cola HBC published its first official integrated report towards the end of 2012.

Coca-Cola HBC proclaimed that, “This first Integrated Report highlights the most material issues, activities, and results of 2012, and tracks the measurable progress the company has made across a range of financial, economic, social, and environmental indicators” (Coca-Cola HBC 2013).

One thing to note is Coca-Cola HBC’s commitment to working with the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC). The IIRC works tirelessly to assist more and more businesses in releasing integrated reports that display their Integrated Bottom Line progress. The Coca-Cola Company is one of seven American companies enrolled in the IIRC pilot programme; the other six are The Clorox Company, Microsoft Corporation, Prudential Financial, Inc., Cliffs Natural Resources, Edelman, and Jones Lang and LaSalle (IIRC 2013). The IIRC is important because as more and more businesses realise the benefits of integrated reporting and join the pilot programme, the more visibility the Integrated Bottom Line method of accounting gains. Ideally, this situation will create a reinforcing loop that continues to add more and more businesses to the ranks of integrated reporting. As more companies adopt this method, the positive effects on the environment and society as a whole will grow.

6 Enabling Organisations

The International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) also works to solidify the exact definition and framework of an integrated report across countries and industries. They launched their proposed framework in mid-April of 2013. The pilot programme that The Coca-Cola Company joined was arranged to help test and provide a trial for a universal standard for integrated reporting. The IIRC postulates that companies need to be more transparent about factors like intellectual property, brand talent, and environmental resources (Hickman and Tysiac 2013), and feels that these items have been “insufficiently integrated into strategic decision-making and reporting.”

The IIRC’s proposed framework focuses on seven key areas. Hickman and Tysiac (2013) summarise these key areas as:

-

1.

Organisational overview. This is a summary of several key aspects affecting a business, including culture, ownership, operating structure, markets, products, revenue, environmental factors, and more.

-

2.

Governance. This section displays a business’s organisational structure including leadership structure, strategic direction, how culture and values affect capitals, and how the governance structure creates value.

-

3.

Opportunities and risks. This area of an integrated report identifies internal and external risks and opportunities and assesses the effects and likelihoods of these events occurring. It will also show steps that are being taken to reduce the likelihood of the risk occurrence.

-

4.

Strategy and resource allocation. This section expounds on where an organisation wants to go and the means with which it will get there. It also discusses how the business plans to deploy resources to implement this strategy.

-

5.

Business model. This section describes key business activities such as innovation, originality in the market, and the adaptability of the business model.

-

6.

Performance. This section describes the organisation’s progress towards its objectives and how the achievement of these goals has affected the company’s financials.

-

7.

Future outlook. This section is for future performance projections as well as any anticipated challenges that the company may face and how it plans to address these challenges.

A comprehensive, transparent report that combines all of the aspects mentioned in the IIRC’s framework will help a company grow as a responsible entity. The added transparency puts more information directly into the hands of shareholders and even other organisations in the industry. Other organisations may see the data from the pilot programme organisation and feel compelled to join in the sustainable movement.

Another organisation that has made strides to universalise the Integrated Bottom Line style of accounting is the Global Reporting Initiative or GRI. It was mentioned previously that Coca-Cola HBC first worked with GRI before signing on to the IIRC’s pilot programme. The Global Reporting Initiative works to help companies reach their sustainable reporting goals. GRI scores companies according to their integrated reporting measures and the level of assurances the company reaches. The panel of external auditors, which includes PricewaterhouseCoopers along with many others, can be called upon to verify the authenticity of their client’s integrated report. A company that works with an external auditor through GRI and receives third party assurance of their integrated accounting methods will receive a good score that will carry more weight in the community than if the company were to self-disclose.

It is also interesting to note that the Global Reporting Initiative cofounded the International Integrated Reporting Council. The IIRC’s primary objective is to clearly define and create global standards for an integrated report.

6.1 Accounting Firms

PricewaterhouseCoopers is a major player in assurances. They have several core competencies in their business, including providing auditing services to their clients. Their work with the GRI shows their commitment to promoting the transparent reporting of corporate social responsibility and other intangible factors. The fact that a benchmark accounting firm such as PricewaterhouseCoopers is on board with integrated reporting and actively advocates its usage is a major victory for advocates of this method.

KPMG is another accounting firm that encourages the use of integrated reporting. KPMG publishes a periodical dedicated to the subject that contains knowledge on Integrated Bottom Line and explains KPMG’s attitude toward the concept. To quote their periodical, “The gap between what companies are doing and what they’re reporting needs closing. Integrated reporting can help companies do this by letting them tell their story on their own terms. It places the responsibility for communicating the business’s story on the reporter rather than a set of reporting rules. This represents a cultural shift from a compliance driven focus to an approach led by business activity and user-needs” (KPMG 2012).

KPMG recommends two steps, in particular, to help reach these goals. First, they believe that a company should build their report around the company’s business model, its strategy for taking advantages of opportunities and facing challenges, and the company’s operational context (KPMG 2012). The second recommended step is to maintain a central thread throughout the centre of the integrated report that links operational strategy, business model, governance, and performance reporting (KPMG 2012).

The fact that two of the biggest accounting firms in the United States endorse the Integrated Bottom Line method and integrated reporting is a huge victory for proponents of the idea.

6.2 Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB)

One of the noteworthy proponents of the integrated reporting cause is Robert Herz. Robert Herz was the chairman of the Financial Accounting Standards Board or FASB from 2002–2010 (Tysiac 2013). Robert Herz spent 28 years as an accountant with Coopers & Lybrand and PricewaterhouseCoopers (Tysiac 2013). Herz is also an accomplished author. He wrote a memoir called Accounting Changes: Chronicles of Convergence, Crisis, and Complexity in Financial Reporting and also co-authored the book The Value Reporting Revolution: Moving Beyond the Earnings Game. Robert Herz openly supports the transparency involved in integrated report. He states, “I think the framework for integrated reporting … is a good framework for thinking about how to communicate the financial information and put it in the context of the whole business and your strategy. What’s your business model? How do you create value over time, and what are the risks and opportunities? All of those things are important things to be able to communicate clearly” (Tysiac 2013).

Another proponent of integrated reporting is Ian Ball. Ball is the chairman of the IIRC working group for integrated reporting and is also the chief executive officer of the International Federation of Accountants (Hoffelder 2012). Ian Ball believes that a more comprehensive approach to reporting would assist shareholders in predicting a company’s power to produce future cash flows (Hoffelder 2012). Specialists in valuing intellectual property contend, “Nearly 80 % of the market value of the S&P 500 could be attributed to intangible assets that are not reported on the balance sheet” (Hoffelder 2012). With this knowledge in mind, Ball argues that the possession of definitive knowledge of intangible assets and environmental/social factors is indispensable in making informed investing decisions (Hoffelder 2012).

6.3 Sustainable Accounting Standards Board (SASB)

The final benchmark proponent is Dr. Jean Rogers. Dr. Jean Rogers is the founder and executive director of the Sustainable Accounting Standards board or SASB. SASB advocates adding corporate non-financial information to a 10-K instead of devising a separate sustainability report (Hoffelder 2013). This categorisation of information will allow for more efficient peer-to-peer comparison and will also force a clearly defined value to be applied to an intangible asset or challenge. SASB works to devise industry specific sustainable accounting standards for publicly traded corporations spanning 80 industries (Hoffelder 2013). Unfortunately, the Securities and Exchange Commission or SEC does not yet mandate sustainable accounting standards, although Dr. Rogers maintains that SASB “has been in constant contact with the SEC throughout its standards initiative” (Hoffelder 2013). Dr. Rogers believes that if accounting standards are modified to include intangibles on a 10-K, the process can be completed in conjunction with the SEC. This would be a triumph for SASB and for all supporters of Integrated Bottom Line accounting.

While there are many defenders of the Integrated Bottom Line concept and the logic supporting it is strong, there are some particular challenges intrinsic to using this method.

7 Challenges

One barrier to a large-scale migration to IBLs and integrated reporting is the short-term thinking employed by many business leaders today. Often those leading large corporations are driven primarily toward efficiency and instantaneous rewards. This may be a winning strategy for a brief time period, but years down the line the decisions made with instant gratification and efficiency in mind may begin to reap dire consequences with regards to the possible release of environmental toxins or waste emissions.

We see measurement as inhibiting progress and placing more focus on risk management. To this end, the sheer number of potential issues, and the expanding range of possible environmental risks, is reflected in the potential indicators and intangibles impacting a bottom line (see Fig. 13.1). These indicators include financial indicators such as: trends in legal compliance; fines, insurance, and other legally related costs; and landscaping, remediation, decommissioning, and abandonment costs. Compounding this is a growing need to measure environmental impacts in terms of new metrics, including: the number of public complaints; the life-cycle impacts of products; energy, materials, and water usage at production sites; potentially polluting emissions; environmental hazards, and risks including the valuation of ecosystem services; waste generation; consumption of critical natural capital; and performance against best-practice standards set by leading customers and by green and ethical investment funds (Elkington 1997).

Another hiccup for integrated reporting is that it currently lacks a clear definition. Many groups such as the GRI, IIRC, and SASB are working tirelessly to provide a framework and direction for companies to strive for while adopting these measures. However, each organisation lends itself to a slightly different point of view. It may require certain legislative bodies enforcing specific guidelines for each company to get on the same page with regards to accounting across countries and industries.

There are two more major barriers to integrated reporting: budget limitations and shortage of expertise. It takes a relatively large sum of money to begin measuring intangible aspects of a business and verifying that information with experts. Verification is a problem in and of itself because there is a dearth of experts in the world that can successfully lead the way even if a company would like to change its accounting methods. The lack of expertise problem should fade as the Integrated Bottom Line method grows in popularity and maturity, but the budget limitation issue will remain even if there is no shortage of experts to offer assurances.

Even with these barriers, integrated reporting is the wave of the future. To quote Peter Bakker, president of the World Business Council on Sustainable Development, “To get all businesses involved in solving the world’s toughest problems, we must change the accounting rules.” A commitment to Integrated Bottom Line reporting will increase brand recognition and goodwill for a company while improving quality of life for stakeholders.

8 A Call to Action

To better understand the paradox of an un-balanced sheet, we have taken a different look at the financial reporting, natural capital, shared value, and risk while exploring new bottom line opportunities. In doing so, this chapter takes a theoretical and practical look at the intersection of accounting and an emerging sustainability performance frontier. We have provided a working definition as the analysis and disclosure of financial, social, and environmental assets and liabilities to the internal and external stakeholders of a firm. This definition takes IBL beyond an accounting practice to position it as a catalyst for sustainable management solutions, risk management and stakeholder engagement.

A review of the literature supported by field studies of multi-national firms shows this area of research and pedagogy will be impactful for both scholars and practitioners. New reporting opportunities include enabling, clarifying, quantifying, valuing, improving, and integrating performance reporting in ways that investors and stakeholders will benefit. It is important that an IBL and integrated reporting become standardised and used across industries. A logical assumption is that investors want more, not less information. If an IBL is sought after by investors, then it will become part of an integrated single report capturing sustainability and financial information.

The steps for accountants and business leaders will be to get top management support to assess an organisation’s current ability to measure and report ESG performance information. By understanding formal and informal systems already in use for the capture and dissemination of performance information, an organisation can ready itself for this coming shift in reporting. If an organisation already has existing sustainability efforts, teams, and a senior manager to lead these initiatives, it is ahead of the game. A renewed urgency to review material financial and non-financial performance measures, while also developing causal models showing the explicit relationships between sustainability practices, natural capital, social performance, and governance, is a logical step toward better understanding your IBL value proposition.

If instead, the organisation finds itself lagging in these areas, know that there are multiple organisations available to help with guidelines on “how to” take on these new reporting opportunities. Opportunities to close the gap between itself and other leading organisations include having the CEO appoint a Corporate Sustainability Officer, and the development of teams to enable, clarify, and quantify new practices and processes. Benchmarking itself and other firms mentioned in this chapter will go a long way toward understanding what it will take to determine the content for the first integrated report.

All firms should consider the tone from the top and include the integration of non-financial performance metrics for use in leadership team meetings including the board of directors. A plan of action for valuing, improving and further integrating IBL and report development will include the organisation’s website and social media, and support of reporting to both internal and external stakeholders. Measurement and reporting needs to be aligned with the business model linked to strategy and shared value creation. As we all know, every issue and opportunity will need to be put into a business context with enough detail for decision makers to understand the implications for business value.

“The profile of corporate stakeholders and their ability to influence business has changed. Companies must demonstrate that they are managing the interests of all their capital providers in order to show that they have a sustainable business model.” (KPMG 2012). This insight should be a wake-up call for business leaders and business schools to uncover and develop new opportunities for measuring and reporting natural capital, risk management, and the ability to leverage management systems that all push the bounds of a new sustainability performance frontier.

Our final question is, in part, a challenge: Are business schools providing a disservice to students and our business systems by not examining and teaching an integrated approach? A well-known thought leader in business management, Peter Drucker, once said, “Every single social and global issue of our day is a business opportunity in disguise” (Drucker Institute 2011). All business professionals across all functional disciplines have an opportunity to be part of this radical transformation. What role will you play?

References

Accounting For a Sustainable Future. (2013). Sustainability accounting standards board. http://www.sasb.org/. Accessed 1 Nov 2013.

Adams, C. (2013). The banking sector and integrated reporting: focus on HSBC. http://drcaroladams.net/the-banking-sector-and-integrated-reporting-focus-on-hsbc/. Accessed 12 July 2013.

American Institute of CPAs. (2013). AICPA annual report. http://www.aicpa.org/About/AnnualReports/DownloadableDocuments/2012-13-AICPA-Annual-Report-Narrative.pdf. Accessed 7 Dec 2013.

Aspen Institute. (2013). Beyond grey pinstripes rankings of MBA programs. http://www.beyondgreypinstripes.org/. Accessed 23 Nov 2013.

Badua, F. A., & Watkins, A. L. (2011). Too young to have a history? Using data analysis techniques to reveal trends and shifts in the brief history of accounting information systems. Accounting Historians Journal, 38(2), 76–77.

Bakker, P. (2012). Prince’s accounting for sustainability project. Keynote address, Geneva. http://www.wbcsd.org/Pages/eNews/eNewsDetails.aspx?ID=15305&NoSearchContextKey=true. Accessed 23 Nov 2013.

Barry, J. S. (2013). The future of sustainability reporting needs CPAs. The CPA Journal, 83(4), 7.

Coca-Cola HBC. (2013). Coca-Cola HBC publishes its first Integrated Report and tenth GRI report. http://www.coca-colahellenic.com/investorrelations/2013-06-07/. Accessed 9 Oct 2013.

Corporate Knight’s Global Green MBA Survey. (2013). Global green MBA survey. http://ggmba.corporateknights.com/. Accessed 22 Nov 2013.

Definition of a Balance Sheet. (2013). Balance sheet. http://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/balancesheet.asp. Accessed 19 April 2013.

Drucker Institute Exchange. (2011). “Opportunity in Disguise Blog Post”, quoting Peter Drucker. http://thedx.druckerinstitute.com/2011/01/opportunity-in-disguise/. Accessed 12 Dec 2013.

Eccles, R. G., & Armbrester, K. (2011). Two disruptive ideas combined: Integrated reporting in the cloud. IESE Insight, 8.

Eccles, R. G., & Krzus, M. P. (2010). One report: Integrated reporting for a sustainable strategy. Chichester: Wiley.

Eccles, R. G., & Serafeim, G. (May 2013). The performance frontier. Harvard Business Review, 50–60.http://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Publication%20Files/May13%20BIG%20Idea%20The%20Performance%20Frontier%20v2_4f46c3d4-d009-4bf5-9162-806af156bcd8.pdf. Accessed 23 May 2013.

Elkington, J. (1994). Towards the sustainable corporation: Win-win-win business strategies for sustainable development. California Management Review, 36(2), 90–100.

Elkington, J. (1997). Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. Oxford: Capstone Publishing.

Global Reporting Initiative. (2012). Integrated Reporting. https://www.globalreporting.org/SiteCollectionDocuments/Integrated-reporting-monthly-report-October-to-December-2011.pdf. Accessed 9 Oct 2013.

Hawken, P. (1993). The ecology of commerce. New York: Harper Collins.

Hickman, A., & Tysiac, K. (April 2013). Integrated reporting takes a big step with international framework draft. Journal of Accountancy.

Hoffelder, K. (2012). The value of sustainability. CFO Magazine (November).

Hoffelder, K. (31 July 2013). Standards call for green disclosure in SEC filings. CFO Magazine. http://ww2.cfo.com/gaap-ifrs/2013/07/standards-call-for-green-disclosure-in-sec-filings/. Accessed 31 July 2013.

Hudson, J., Jeaneau, H., & Zlotnicka, E. (2012). “Q-Series” What is integrated reporting. UBS investment research. http://www.theiirc.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/UBS-What-Is-Integrated-Reporting.pdf. Accessed 6 Dec 2013.

IIRC Pilot Programme. (2013). International Integrated Reporting Council. http://www.theiirc.org/companies-and-investors/. Accessed 1 Nov 2013.

Institute RSE Management. (2012). The Grenelle II Act in France: A milestone towards integrated reporting. http://www.capitalinstitute.org/sites/capitalinstitute.org/files/docs/Institut%20RSE%20The%20grenelle%20II%20Act%20in%20France%20June%202012.pdf. Accessed 12 Dec 2013.

Jagannath, A., & Koller, T. (2013). Building a better income statement. http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/corporate_finance/building_a_better_income_statement. Accessed 6 Dec 2013.

KPMG. (2012). Integrated reporting: Performance insight through better business reporting. KPMG Integrated Reporting, 2. http://www.kpmg.com/Global/en/IssuesAndInsights/ArticlesPublications/integrated-reporting/Documents/integrated-reporting-issue-2.pdf. Accessed 12 Dec 2013.

Lovins, H. (2006). Sustainable executives, effective executive. http://www.natcapsolutions.org/publications_files/2006/MAY06_India_EffectiveExecutive.pdf. Accessed 15 April 2013.

Lovins, A. (2011). Reinventing fire: Bold business solutions for the new energy era. White River Junction: Chelsea Green.

Lovins, H., Hohensee, J., & Sheldon P. (2010). Integrated bottom line concept paper. Natural Capital Solutions. Duquesne Program.

Main, N., & Hespenheide, E. (2013). Integrated reporting. Deloitte Review. http://www.deloitte.com/view/en_US/us/Insights/Browse-by-Content-Type/deloitte-review/f44a8df050a05310VgnVCM2000001b56f00aRCRD.htm. Accessed 6 Dec 2013.

Novo Nordisk. (2013a). Managing using the triple bottom line business principle. CSR Europe. http://www.csreurope.org/novo-nordisk-managing-using-triple-bottom-line-business-principle#.UlXIbGT723M. Accessed 9 Oct 2013.

Novo Nordisk. (2013b). Sustainability–Novo Nordisk A/S. http://novonordisk.com/sustainability/. Accessed 9 Oct 2013.

Pilot Programme Business Network. (2013). October 29-last update. http://www.theiirc.org/companies-and-investors/pilot-programme-business-network/. Accessed 1 Nov 2013.

Porter, M., & Kramer, M. (2011). Creating shared value: How to reinvent capitalism and unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harvard Business Review, 89(1/2), 62–77.

Prince’s Accounting For Sustainability Project. (2013). The prince’s accounting for sustainability project. http://www.accountingforsustainability.org/. Accessed 1 Nov 2013.

Savitz, A. W., & Weber, K. (2006). The triple bottom line: How today’s best-run companies are achieving economic, social, and environmental success–and how you can too. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Sroufe, R., Steele, A., & Jolliff, D. (2012). Operationalizing sustainability: Clarity and compliance project. http://www.duq.edu/Documents/business/beard-institute/Operationalizing%20Sustainability%20Project%20White%20Paper.pdf. Accessed 22 Nov 2013.

Sustainability-Coca-Cola Journey. (2013). Sustainability. http://www.coca-colacompany.com/topics/sustainability. Accessed 9 Oct 2013.

Tysiac, K. (2013). Managing change, people and transparency: An interview with former FASB chairman Robert Herz. Journal of Accountancy, 216(1), 40–45.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sroufe, R., Ramos, D. (2015). The Un-balanced Sheet: A Call for Integrated Bottom Line Reporting. In: O'Riordan, L., Zmuda, P., Heinemann, S. (eds) New Perspectives on Corporate Social Responsibility. FOM-Edition. Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-06794-6_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-06794-6_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden

Print ISBN: 978-3-658-06793-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-658-06794-6

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsBusiness and Management (R0)