Abstract

More than 40 % of the world’s 4 billion hectares forests are located in tropical regions and cover 1.73 billion hectares which corresponds to nearly half of the tropical land area. Deforestation – mainly the conversion of tropical forests to agricultural land – shows signs of decreasing in several countries but continues at a high rate in others. Around 8 million hectares of tropical forest were converted to other uses or lost through natural causes each year in the last decade compared to more than 10 million hectares per year in the 1990s. Fifteen tropical countries loose more than 1 % of their forests per year, in five countries forest area is stable, and in nine countries forest area is slightly increasing by a total of 0.3 million hectares per year.

Half of the world’s growing stock is located in tropical forests. In terms of carbon content, they have a share of about 60 %. On average, tropical forests in Africa and Latin America/Caribbean store 100 t carbon per ha, in Asia/Pacific 75 t carbon per ha.

Primary forest, i.e., forest of native species where there are no clearly visible indications of human activities and the ecological processes have not been significantly disturbed, includes the most species-rich, diverse terrestrial ecosystems. In Africa and Asia/Pacific, the share of primary forests on total tropical forest area is 42 %, while in Latin America/Caribbean still 74 % are primary. Overall, the area of primary forests is decreasing in all tropical regions with about 3.7 million hectares per year, but the situation seems to be improving especially in Asia/Pacific, while the rates of conversion show an increasing trend in Latin America/Caribbean.

About 15 % of tropical forests are designated as primary function for the conservation of biodiversity.

National parks, game reserves, wilderness areas, and other legally established protected areas also cover about 15 % of the total tropical forest area. The primary function of these forests may be the conservation of biological diversity, the protection of soil and water resources, or the conservation of cultural heritage.

Half of all tropical countries declare forest fires as severe problem. Severe storms, flooding, and earthquakes have also damaged areas of forests. Nearly all countries in the tropics face at least forest degradation as result of the impact of human interventions in production forests, protected areas and parks. In many tropical countries, the climate appears to be changing. Recent data provide evidence of, for example, increasing temperatures and prolonged dry periods in some regions and increased rainfall and more frequent tropical storms in others.

Half of the tropical forest is designated as permanent forest estate (PFE). Again half of these, about 400 million hectares, serve production purposes. Due to accessibility problems, only parts of the production forests are available for harvest. About 3 % of the permanent forest estate is planted forest. Reported wood removals amount to 1.3 billion cubic meters annually and equivalent to 0.5 % of the total growing stock. By far the most important product is fuelwood, although the statistics on this product are neither complete nor precise. Only few tropical countries are able to report on amount and value of non-timber forest products.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Biodiversity

- Carbon content

- Climate change

- Conversion of tropical forests

- Deforestation

- Primary tropical forests

- Tropical forests

- Tropical forest resources

Introduction

During the last decade, the information on tropical forests improved considerably. Though still many information gaps exist, an attempt is made to summarize current knowledge on state of the forests and forestry in tropical countries. The following analysis is based on data (see Annex) compiled from:

-

1.

Global Forest Resources Assessment 2010 and associated remote sensing analyses (FAO 2010)

-

2.

ITTO (Blaser et al. 2011): ITTO producer countries (33 countries representing more than 80 % of the total tropical forest area)

-

3.

FCPF (Country Readiness Preparation Proposals: http://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org): all participating countries as supplement

-

4.

Country data presented at official websites: all countries with low information status as supplement.

Considered are all countries situated in the tropical regions as listed by ITTO and FAO (65 countries) as well as Nepal which is listed by FAO only. The descriptions follow the structure of the Forest Resources Assessment (FAO 2010).

A fundamental difficulty in reporting tropical forest area is that many countries have more than one climatic domain. For example, China and the United States both have tropical forest but they are a fraction of forest area. Likewise, while Peru has substantial tropical forest and is an ITTO producer country, they also have significant forest that is not tropical. Thus, one must take care in interpreting forest area based on country alone unless the country has reported forest area by forest type. Of the analyses presented in this chapter, only the remote sensing work of the Global Forest Resources Assessment (FRA) reports forest area and change based on climatic ecozones (Table 1).

Extent of the Tropical Forest Resource

Extent, Naturalness, and Designation

Tropical forests form a variety of unique ecosystems leading to the rich diversity of the tropics. Tropical rainforests merge into other types of forest depending on the altitude, latitude, and various soil, flooding, and climate conditions. They occur in the equatorial zone, within the area bounded by latitudes 23.5° N (Tropic of Cancer) and 23.5° S (Tropic of Capricorn). One of the major characteristics of tropical forests is their distinct seasonality: winter is absent, and only two seasons may occur. The length of daylight is 12 h and varies little. The seasonal distribution of rainfalls determines the subdivision in:

-

Evergreen rainforest: no dry season.

-

Seasonal rainforest: short dry period in a very wet tropical region (the forest exhibits definite seasonal changes as trees undergo developmental changes simultaneously, but the general character of vegetation remains the same as in evergreen rainforests).

-

Semievergreen forest: longer dry season (the upper tree story consists of deciduous trees, while the lower story is still evergreen).

-

Moist/dry deciduous forest (monsoon): the length of the dry season increases further as rainfall decreases (all trees are deciduous).

-

http://www.srl.caltech.edu/personnel/krubal/rainforest/Edit560s6/www/where.html

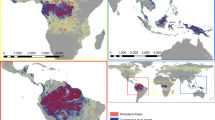

The bulk of the world’s tropical rainforest occurs in the Amazon Basin in South America. The Congo Basin and Southeast Asia, respectively, have the second and third largest areas of tropical rainforest. Rainforests also exist on some the Caribbean islands, in Central America, in India, on scattered islands in the South Pacific, in Madagascar, in West and East Africa outside the Congo Basin, in Central America and Mexico, and in parts of South America outside the Amazon. Brazil has the largest extent of rainforest of any country on Earth.

According to FAO, tropical forests extend on 1.70 billion hectares in 2010 based on Landsat image analysis (Table 5, Table 1).

The world’s forests are distributed unevenly with just under half the world’s forests in the tropical domain (45 % of total area), about one third in boreal (31 %) and smaller amounts in temperate (16 %) and subtropical (8 %) domains. Figure 1 shows regional differences in the rate of change in forest area. The highest rate of forest conversion to other land uses was in South America, followed by Africa and Asia. Net forest loss in the tropical domain was reasonably constant from 1990 to 2010, going from 6 million hectares per year in the 1990s to 7 million hectares per year in the 2000s.

About half of the land area in the tropics is covered by forests. Forest coverage is highest in Latin America/Caribbean (56 %), followed by Africa (48 %) and Asia/Pacific (39 %). On country level, the highest coverage (85–98 %) is found in Gabon, Suriname, and French Guyana. Only few forests (4–7 % coverage) exist in Togo, Burundi, Kenya, and Haiti.

ITTO producer countries are covered by 1.42 billion hectares tropical forests following FAO, but ITTO estimates the extent in a range between 1.30 and 1.39 billion hectares. While FAO includes the total forest area of India and Mexico (133 million hectares), ITTO estimates the area of tropical forests only (69 million hectares). Only ten of the 33 ITTO producer countries correspond to FAO figures. Seven countries conduct no forest inventory, 2 countries prepare for their first inventory, 10 countries request inventories only within the forest management units (FMUs), 5 countries rely on inventories conducted before 2000 and 8 countries accomplished their last inventory during the previous decade (Table 5, Annex 2).

The Permanent Forest Estate in Tropical Countries

ITTO reported that some 910 million hectares are primary forests, of these 870 million hectare are in ITTO producer countries. Half of the forest area serves no designated purpose. In tropical Africa 60 % of the forest area has no defined status, in Asia/Pacific its 44 % like in Latin America/Caribbean (45 %). 880 million hectares are designated as permanent forest estate (PFE), of these 780 million hectares are in ITTO producer countries. Nearly 3 % of the PFE are planted forests, i.e., 0.4 % in Africa, 7 % in Asia/Pacific, and 2 % in Latin America/Caribbean. The PFE serves production purposes (55 % of the area) as well as protection services (45 %). In Latin America/Caribbean, the area of forests for protection exceeds that of production forests (Table 2).

More than half of the tropical forest is closed forest whose tree canopy covers 60 % or more of the ground surface, when viewed from above. In Africa, on average 60 % of the forest area is closed. The highest ranking is found in Liberia and Gabon, but the canopy covers less than 20 % in Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria, and Togo. In Asia/Pacific, on average 51 % of the forests are closed namely in Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, and Malaysia. In contrast, India has a low proportion of closed forests. In Latin America/Caribbean, more than half of the forests (55 %) are closed in all countries except Mexico. Suriname and Guyana show the highest ranking of all ITTO producer countries in terms of closed forests.

Annual Change Rates

Annual change rates in tropical forest area vary slightly between FAO and ITTO estimates (Table 4, Annex 1). Greatest discrepancies exist in Nigeria, Cameroon, Mexico, and Peru.

Annual change rates range from −5, to 75 % in Togo to +1.1 % in Viet Nam. The total gross annually deforested area in the tropics between 2005 and 2010 is 8.2 million hectares, when considering new plantations, the annually affected net area is reduced to 7.9 million hectares.

The highest annual losses are observed in Brazil (−2.2 million hectares), Indonesia (−0.7 million hectares), Nigeria and Tanzania (−0.4 million hectares), and Cameroon, Democratic Republic of Congo Zimbabwe, Bolivia, and Venezuela (about −0.3 million hectares).

In all tropical regions, deforestation is driven primarily by conversion to agricultural land use. Additionally, in Africa fuelwood gathering and charcoal production play an important role – but one that is not well quantified. The Asia/Pacific regions suffer periodically from destruction by fires. In Latin America/Caribbean, mining and infrastructure development are also important drivers.

In some tropical countries, the forest area is extending namely in India and Viet Nam as well as, though on lower level, in Costa Rica and Cuba. Still, reafforestation in tropical regions reduces tropical forest losses only by about 0.3 million hectares per year.

Growing Stock and Carbon Stocks

Half of the world’s growing stock is located in tropical forests. The majority is stocking in Latin America/Caribbean (62 % with 48 % in Brazil) followed by Africa (27 %) and Asia/Pacific (11 %) (Table 5, Annex 2).

FRA 2010 estimates that the world’s forests store 289 gigatonnes (Gt) of carbon in their biomass alone. Tropical forests have a share of about 60 %. Carbon in tropical forests is again concentrated in Latin America/Caribbean (55 % with 37 % in Brazil) followed by Africa (29 %) and Asia/Pacific (16 %). On average. tropical forests in Africa and Latin America/Caribbean store 100 t carbon per ha, in Asia/Pacific 75 t carbon per ha. While sustainable management, planting, and rehabilitation of forests can conserve or increase forest carbon stocks, deforestation, degradation, and poor forest management reduce them. Information on changes in carbon stocks is scarce. For reporting period 2005–2010, most countries report not significant changes, only Indonesia (−1.7 t/ha/year) and Malaysia (−0.8 t/ha/year) provided data.

Biodiversity in Tropical Forests

Area of Primary Forests

Forests of native species where there are no clearly visible indications of human activities and the ecological processes have not been significantly disturbed are considered as primary forests. They include the most species-rich, diverse terrestrial ecosystems. More than half of the tropical forests worldwide, i.e. 0.91 billion hectares, are primary forests (Table 6, Annex 3). In Africa and Asia/Pacific, the share of primary forests on total tropical forest area is 42 %, while in Latin America/Caribbean still 74 % are primary. The decrease of primary forests during the last decades is largely due to reclassification of primary forest to "other naturally regenerated forest" because of selective logging, shifting cultivation, and other human interventions. Overall, the area of primary forests is decreasing in all tropical regions at a rate of about 3.7 million hectares per year, but the situation seems to be improving especially in Asia/Pacific, while the rates of conversion show an increasing trend in Latin America/Caribbean. More than 70 % of all losses of primary tropical forests occur in Brazil although this seems to be slowing in recent years. Relatively high conversion rates are also observed in Papua New Guinea and Gabon.

Forest Area Designated for Conservation of Biological Diversity

About 15 % of tropical forests are designated as primary function for the conservation of biodiversity (Table 6, Annex 3). This is more than the global average of about 13 %. Only five countries in the tropics were not able to report on biodiversity conservation areas though for instants countries like Kenya and the Dominican Republic are known for their nature reserves. The highest share of biological diversity conservation areas which are tropical forests is found in the Asia/Pacific region. Most, but by far not all of these areas are legally established protected areas. This is especially true for Latin America/Caribbean.

Tropical Forests in Protected Areas

National parks, game reserves, wilderness areas, and other legally established protected areas also cover about 15 % of the total tropical forest area (Table 6, Annex 3). The primary function of these forests may be the conservation of biological diversity, the protection of soil and water resources, or the conservation of cultural heritage.

In Africa and Latin America/Caribbean, the share of legally protected area is about 12 % of the total tropical forest area, while in Asia/Pacific the share amounts to 28 %. The situation varies widely between countries. The highest shares with more than half of the total forest area in a legally protected status are found in Thailand, Nicaragua, and Panama.

Health and Vitality of Tropical Forests

Forest Fires

While some forest ecosystems depend on fire for their regeneration, forest fires can be devastating to others and also frequently cause loss of property and human life. In tropical forests, less than 1 % of all forests were reported to be significantly affected each year by forest fires. However, the area of forest affected by fires was severely underreported, with information missing from many countries. Still, half of all tropical countries declare forest fires as severe problem. The greatest damaged areas are reported from India, Ghana, Cameroon, and Myanmar (Table 7, Annex 4). Less than 10 % of all forest fires are prescribed burning; most are classified as wildfires.

Pests and Diseases, Natural Disasters , and Invasive Species

Information availability and quality continues to be poor for most of these disturbances. Outbreaks of forest insect pests are reported from India, Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Peru. Severe storms, flooding, and earthquakes have also damaged large areas of forests. During the last 15 years, hurricanes hit especially Myanmar, Guatemala, Honduras, Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Jamaica. Mozambique, Indonesia, Myanmar, and Thailand suffered from severe flooding. Earthquakes destroyed parts of Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, El Salvador, and Haiti.

Woody invasive species are of particular concern in small island developing states, where they can threaten the habitat of endemic species.

Human-Induced Disturbances

Healthy biological functioning of forest ecosystems can be affected by a variety of human actions such as encroachment, illegal harvesting, human-induced fire and pollution, grazing, mining, poaching, etc. Nearly all countries in the tropics face at least forest degradation as result of the impact of human interventions in production forests, protected areas, as well as in parks.

Climate Change

ITTO producer countries were asked to specify their expectations concerning the vulnerability of their forests to climate change (Table 7, Annex 4). Blaser et al. (2011) concluded: “Climate change and climate variability could be among the most serious threats to sustainable development, with potential adverse impacts on natural resources, physical infrastructure, human health, food security and economic activity. Forests and rural landscapes in the tropics may be particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate variability, for example extreme weather events such as droughts (and associated wildfires), flooding and storms. At the same time, forests have the capability to reduce both environmental and social vulnerability.

In many tropical countries the climate appears to be changing. Recent data provide evidence of, for example, increasing temperatures and prolonged dry periods in some regions, and increased rainfall and more frequent tropical storms in others. In Mexico, there has been an increase in mean annual temperature of 0.6 °C in the past four decades. In Peru, average annual temperature has increased by 0.3 °C in the last 50 years. In Ghana, average annual temperature has increased by 1.0 °C since 1960, thus damaging the integrity of forest ecosystems. Adaptive approaches to forest management will become increasingly important in the face of climate change. Regardless of the pace of such change, healthy forests maintained under SFM will be better able to cope than those weakened and/or degraded by over-exploitation.”

Productive Functions of Tropical Forests

Areas Designated for Productive Functions

Half of the tropical forest is designated as permanent forest estate (PFE) . Again half of these, about 400 million hectares, serve production purposes. In Asia/Pacific, production forests have a share of more than one third of the total forests.

ITTO producer countries report on their production forests in more detail (Table 3). Due to accessibility problems, only parts of the production forests are available for harvest. In Latin America/Caribbean, only one fourth of these forests can be exploited, while in Africa nearly two thirds are accessible. In Asia/Pacific, half of the production forests are covered by management plans. This share is with 20 % lowest in Latin America/Caribbean. Certification also plays a minor role in Latin America/Caribbean. Still, up to now the area of certified forests is slightly increasing throughout the tropics but especially some countries in Latin America/Caribbean observe nonrenewals of certificates because demand for certified timber is lacking.

Planted Forests

About 3 % of the permanent forest estate is planted forest. During the decade 2000–2010, there is a decreasing trend in forest plantations in Angola, Burundi, Papua New Guinea, and Sri Lanka. In half of the tropical countries, the plantation area did not change significantly, but 28 countries show an increasing trend, especially Brazil, Viet Nam, Malaysia, Peru, Myanmar, Ghana, Colombia, and Ecuador.

Removals of Wood Products

Reported wood removals amount to 1.3 billion cubic meters annually and equivalent to 0.5 % of the total growing stock (Table 8, Annex 5). Most countries have a stable timber production level. By far the most important product is fuelwood. Since some countries regard fuelwood as non-timber forest product (NTFP) and do not include this wood in their statistics, the actual amount of wood removals is undoubtedly higher than reported. There is also no estimate on informally and illegally removed wood. About 1.5 % of the harvested wood is exported.

Forest Management for Production

More than half of all tropical countries developed forestry guidelines, six of them have none (Table 5, Annex 2). Twenty out of 65 countries conducted a national forest inventory, 16 countries conduct inventories in their forest management units (FMUs), 7 countries definitely have no inventory information, the situation in the remaining counties is unknown. The monitoring capacity is low in most countries; high capacities are reported by Côte d’Ivoire, India, Malaysia, Brazil, Guyana, and Mexico.

Seventeen countries contract out concessions which differ considerably in size and duration between countries (Table 8, Annex 6). Thirteen countries offer short-term harvest permits. Usually, standards for harvest are set and minimum diameter rules for species or species groups are prescribed. Ten countries are committed to reduced impact logging systems (RIL), but chainsaw logging and high grading are still widespread. Most countries rely on successful natural regeneration, but 12 countries also use enrichment planting.

Removals of Non-wood Forest Products

Only few tropical countries are able to report on amount and value of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) such as Brazil, Colombia, India, Malaysia, Mexico, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Tanzania, and The Philippines. The major categories of NWFP removals about which countries provided the most information are (in descending order of importance):

-

1.

Food

-

2.

Exudates

-

3.

Other plant products

-

4.

Wild honey and beeswax

-

5.

Ornamental plants

-

6.

Raw materials for medicine and aromatic products

-

7.

Wild meat

-

8.

Raw materials for utensils, handicrafts and construction

-

9.

Living animals

-

10.

Hides, skins, and trophies

Some countries, especially in Latin America/Caribbean, introduced or are introducing markets to facilitate payments for environmental services (PES) such as water catchment protection, biodiversity conservation, and carbon sequestration. At the international level, the volume and value of payments is still low, but it is expected that there is substantial potential for an increase, especially for carbon sequestration.

Protective Functions of Tropical Forests

Forest Area Designated for Soil and Water Conservation

One of the most important protective function of forests is related to soil and water resources. Forests conserve water by increasing infiltration, reducing runoff velocity and surface erosion, and decreasing sedimentation. Forests play a role in filtering water pollutants, regulating water yield and flow, moderating floods, enhancing precipitation, and mitigating salinity. The forest area with “protection of soil and water as the primary designated function” refers specifically to the area of forests that have been set aside for the purposes of soil and water conservation, either by legal prescription or by decision of the landowner or manager. More specifically, the variable refers to soil and water conservation, avalanche control, sand dune stabilization, desertification control, and coastal protection. It does not include forests that have a protective function in terms of biodiversity conservation or those in protected areas, unless the main purpose is soil and water conservation.

Following FAO, about 133 million hectares or nearly 8 % of the tropical forests have soil and water conservation as their primary objective (Table 6, Annex 3). The quantification of the protection forest area remains difficult. ITTO producer countries report much greater areas especially in Latin America. Brazil reported 43 million hectares forest designated for soil and water protection to FAO. The ITTO report states: “The Amazon Basin produces 20 % of the world’s freshwater; it is therefore vital that its soil and water resources are properly protected. An estimated 243 million hectares of forest in Brazil are managed primarily for soil and water protection.”

In Africa, the greatest protective forests are located in Mozambique, Central African Republic, and the Republic of Congo. In Asia Pacific, Indonesia, Myanmar, Lao PDR, and Vietnam have the greatest protective forests. In Latin America/Caribbean, they are found in Brazil, Venezuela, and Colombia.

Socioeconomic Functions of Tropical Forests

Ownership and Management Rights

In African tropical countries, most of the forests are in public ownership . Significant private ownership exists in Sierra Leone (86 % belong communities), Togo (73 % belong individuals), Uganda (68 %), Kenya (61 % belong mainly communities), Zimbabwe (32 %), and Central African Republic (9 %). The holder of management rights in public forests is usually public administrations or in few cases communities. In those countries where concessions for timber harvest are granted, business entities hold management rights for a given period.

In Asia/Pacific as well as in Latin America/Caribbean, private forest ownership is much more spread especially in Papua New Guinea (97 %), Fiji (95 %), Timor Leste (67 % belong communities), El Salvador (69 %), Colombia (67 %), Jamaica (65 %), Paraguay (61 %), and Guatemala (52 %). Still, the holder of management rights are mainly public administrations.

Public Expenditure and Revenue Collection

Thirty-one of 65 tropical countries reported on revenues from forestry and public expenditure for forestry measures in 2005 (FAO 2010). On average, total forest revenue collection was about US$4.4 per hectare, ranging from US$0.3 per hectare in tropical Africa to US$6.6 per hectare in tropical Asia/Pacific. Public expenditures range from US$0.7 per hectare in tropical Africa to US$2.5 per hectare in Asia/Pacific. In Latin America/Caribbean, the situation is dominated by Brazil. Here, revenue collection is relatively high with more than US$5 per hectare, and public expenditures are low. Without Brazil, the relation of revenues (US$0.7 per hectare) and expenditures (US$1.9 per hectare) are similar to the African situation. Only in Asia/Pacific, namely, Malaysia and Papua New Guinea, and Brazil revenues are higher than expenditures.

Value of Wood and Non-wood Forest Product Removals

Forty-four tropical countries report on values of wood and non-wood forest removals in 2005 (FAO 2010). Wood removals valued just over US$25.7 billion annually in the period 2003–2007, accounted for by industrial roundwood (60 %) and woodfuel (40 %). In Liberia, Burundi, Madagascar, Rwanda, Tanzania, India, and Myanmar, the value of woodfuel trade exceeds that of industrial roundwood.

The reported value of non-wood forest product removals amounts to about US$0.8 billion for 2005. Food products account for the greatest share. However, information is still missing from many countries in which non-wood forest products are highly important, and the true value of subsistence use is rarely captured. As a result, the reported statistics probably cover only a fraction of the true total value of harvested non-wood forest products. High values are reported by Brazil, Colombia, and India. Millions of people depend on food, medicine, and products from the forest in their daily life. Some ITTO producer countries estimated the number of depending people such as 45 million in the Democratic Republic of Congo, 48 million in Nigeria, 115.5 million in Cambodia, 38 million in Myanmar, more than 200 million in India, more than 5 million in Papua New Guinea, 25 million in the Philippines as well as in Thailand, and 12 million in Mexico.

Payment for environmental services (PES) may generate additional income, but are not fully established yet. PES mainly for the management of water catchments is practiced in Kenya, Fiji, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Guyana, Mexico, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, and Paraguay. Regional initiatives or pilot projects are conducted in Madagascar, Indonesia, Vietnam, Panama, and El Salvador.

Employment

During the last decade, reported employment in forest establishment, management, and use employment increased in 14 countries especially in Malaysia, Vietnam, and Paraguay – probably because roundwood production has increased faster than gains in labor productivity. Employment decreased in 9 countries, especially in Indonesia and Jamaica. Some countries reported increased employment in management of protected areas such as Nigeria, Zimbabwe, and Vietnam. Given that much forestry employment is outside the formal sector, forest work is surely much more important for rural livelihoods and national economies than the reported figures suggest.

Area of Forest Designated for Social Services

The forest area designated for recreation, tourism, education, or conservation of cultural and spiritual heritage is expanding in the tropics. Roughly about 0.17 million hectares or about 10 % of the tropical forest are designated for the provision of social services. Brazil has designated more than one fifth of its forest area for the protection of the culture and way of life of forest-dependent people.

References

Available for harvest: UNEP (2011) National environmental summary Belize. http://www.pnuma.org/publicaciones/NES%20Final%20March%2019%202012-%20FINAL.pdf

Belize: Laws: http://www.forestdepartment.gov.bz/index.php/legislation

Benin: USAID 2007. 118/119 Biodiversity and Tropical Forest Assessment for Benin. http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADK459.pdf. Accessed Aug 2012

Blaser J, Sarre A, Poore D, Johnson S (2011) Status of Tropical Forest Management 2011. ITTO technical series no 38. International Tropical Timber Organization, Yokohama, Japan

Blomley T, Iddi S (2009) Participatory Forest Management in Tanzania: 1993 – 2009 Lessons learned and experiences to date. http://www.tzdpg.or.tz/uploads/media/EXPERIENCE_AND_LESSONS_LEARNED_IN_PARTICIPATORY_FOREST_MANAGEMENT_1_.pdf. Accessed Aug 2012

Brunei Darussalam: Muhd Safwan, Abdullah Bibi, Zaeidi Haji Berudin (2008) (?) Forest land management in Brunei Darussalam. http://www.docstoc.com/docs/44766877/Background-of-Forestry-in-Brunei-Darussalam

Burundi: Hobbs M, Knausenberger W (2003) BURUNDI Environmental Threats and Opportunities Assessment (ETOA). Supplement to the 2003–2005 USAID/Burundi Integrated Strategic Plan. www.encapafrica.org/documents/biofor/BurundiETOAfinal.doc

Cameroon, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Central African Republic, Congo, DRC: de Wasseige C, Devers D, de Marcken P, Eba’a Atyi R, Nasi R, Mayaux Ph (eds) (2009) The Forests of the Congo Basin – State of the Forest 2008. Publications office of the European Union, Luxembourg. ISBN 978-92-79-13210-0, doi: 10.2788/32259

Congo Rep. (timber tracking system), Guatemala + Mozambique (conflicts), Sri Lanka (Poor practices, mining, law enforcement): Williams LG, Davis C, Lupberger S, Daviet F (2012) Getting ready with forest governance: a review of the forest carbon partnership facility readiness preparation proposals and the UN-REDD National Programme Documents, v 1.9. WRI working paper. World Resources Institute, Washington, DC. http://www.wri.org/publication/getting-ready. Accessed 21 Jan 2013

Costa Rica: Ferroukhi L (ed) (2003) Municipal Forest Management in Latin America. CIFOR, IDRC, Bogor

Cuba: Lambert M (2008) Forestry management in Cuba: an environmental history of the 20th century. Honours Thesis Dalhousie University http://environmental.science.dal.ca/Files/Meghan_Lambert_1%2B2.pdf

Dangal SP, De Silva PMA (2010) Community forest management in Sri Lanka “lesson learnt and future direction”. http://www.forestrynepal.org/images/02-%20Presented%20Papers%20and%20Powerpoints/Theme%201/Paper/07-%20Dangal%20et%20al_Sri%20Lanka.pdf

Deforestation: http://www.forestdepartment.gov.bz/index.php/programs/60-the-law-enforcement-program

Dominican Republic: REDD in Dominican Republic. http://www.theredddesk.org/sites/default/files/resources/countries/readiness_overview/dominican_republic_readiness_overview_the_redd_desk_2012.pdf. Accessed Aug 2012

Enforcement: http://www.theredddesk.org/countries/laos/readiness_overview#rights_and_tenure. Accessed Aug 2012

Equatorial Guinea: Mugnier A, Martinez-Plaza S (2008/2009) The Forests of Equatorial Guinea in 2008. In: de Wasseige C, Devers D, de Marcken P, Eba’a Atyi R, Nasi R, Mayaux Ph (eds) The Forests of the Congo Basin – State of the Forest 2008. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. ISBN 978-92-79-13210-0, doi: 10.2788/32259 http://www.observatoire-comifac.net/docs/edf2008/EN/SOF_04_EquatoGuinea.pdf

FAO (2010) Global forest resources assessment 2010. FAO forestry paper 163. Rome

PNG Forest Authority 2003. Application of national criteria and indicators for sustainable management of natural tropical forests. http://www.forestry.gov.pg/site/files/c%20&%20i%20pdf%20file.pdf. Accessed Jul 2012

Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) (2013) Country-readiness-preparation proposals: http://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org. Accessed 12 Mar 2013

Forest Investment Programme (FIP) (2013) https://www.climateinvestmentfunds.org/cif/node/5. Accessed 12 Mar 2013. FIP countries: Brazil, Burkina Faso, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Indonesia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Mexico, Peru

Government of Brunei Darussalam (2009) 4th national report convention on biological diversity. http://www.cbd.int/doc/world/bn/bn-nr-04-en.pdf

Guinea: kfw 2010: Guinea: Forestry Programme (Phase I) Management of Forest and Rural Resources (Phase II). http://www.kfw-entwicklungsbank.de/ebank/EN_Home/Evaluation/Ex-post_evaluation_reports/PDF-Dokumente_E-K/Guinea_Forstprogramm_2010_EN.pdf

Haiti: http://healthyforests.wordpress.com/tag/deforestation/

IFM in Nicaragua: http://www.globalwitness.org/campaigns/environment/forests/independent-monitoring/nicaragua

Inventory: http://www.whrc.org/education/vietnam/pdf/VIET%20NAM%20FOREST%20INVENTORY.pdf

Jamaica: http://www.forestry.gov.jm/home_new.html. Accessed July 2012

Kenya: Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources: sessional paper no. 1 of 2007 on forest policy. http://www.kenyaforestservice.org/images/MMMB/forest%20policy%202007.pdf. Accessed July 2012

Lao PDR, Nepal, Vietnam: ASIA-Pacific Forestry Commission (2010) ASIA-pacific forests and forestry to 2020. Report of the second asia-pacific forestry sector outlook study. Rap publication 2010/06. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific

Law (2011) http://www.theredddesk.org/sites/default/files/resources/countries/readiness_overview/peru_ro_en.pdf. Accessed July 2012

National Forest Management and Conservation Plan (2001) http://www.forestry.gov.jm/PDF_files/ForestPlan.pdf

Nepal: Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Singha Durbar, Kathmandu, Nepal (2009) Nepal forestry outlook study. Food and agriculture organization of the united nations, regional office for asia and the pacific. Working Paper no. APFSOS II/WP/2009/05 http://www.fao.org/docrep/014/am250e/am250e00.pdf

NFI: http://www.fao.org/forestry/17847/en/tza/ National forest assessments- country projects: Brazil, Costa Rica, Gambia, Guatemala, Philippines, Tanzania

Nicaragua: http://www.reforestationinvestments.com/nicaragua.shtml

Other partner countries supported by UN-REDD: Argentina, Bangladesh, Benin, Bhutan, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Mexico, Mongolia, Morocco, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Peru, South Sudan, Sudan, Suriname and Uganda

Papua New Guinea: Enhancing Forest Law Enforcement in Papua New Guinea. ITTO Project PD 449/07 Rev. 2. http://www.forestry.gov.pg/site/files/Project%20Brochure.pdf. Accessed Jul 2012

Paraguay: UNREDD/PB%/2010/10. National Programme Document – Paraguay. www.unredd.net/index.php?option…gid

Partner countries: Bolivia, Cambodia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ecuador, Indonesia, Nigeria, Panama, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Philippines, The Republic of the Congo, Solomon Islands, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, Viet Nam, Zambia

Peru RIL: http://www.forestlegality.org/risk-tool/countries/peru

PES: AGF: (2012) Study on forest financing. Advisory Group on Finance. Collaborative Partnership on Forests. www.un.org/esa/forests/pdf/AGF_Study_July_2012.pdf

Production, export (non-ITTO countries): FAO 2012: FAO Yearbook Forest Products 2006–2010. FAO Forestry Series No. 45 FAO Statistics Series No. 201

UN-REDD Programme (2013) http://www.un-redd.org/aboutredd/tabid/582/default.aspx. Accessed 12 Mar 2013

REDD Country Candidates: Belize, Bhutan, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Chad, Cote d’Ivoire, Dominican Republic, Fiji, Jamaica, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Togo, Uruguay

REDD+ Country Participants: Argentina, Bolivia, Cameroon, Cambodia; Central African Republic, Chile, Colombia, DRC, Congo, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Indonesia, Kenya, Lao PDR, Liberia, Madagascar, Mexico, Mozambique, Nepal, Nicaragua, Panama, PNG, Peru, Suriname, Tanzania, Thailand, Uganda, Vanuatu, Vietnam

Sierra Leone: government of Sierra Leone, United Nations Development Programme 2007. Capacity building for sustainable land management in sierra leone. http://www.sl.undp.org/2_focus/capacity_build_sustainable_lm_sl.pdf. Accessed Aug 2012

Solomon Islands: Pauku R L (2009) Solomon Islands forestry outlook study food and agriculture organization of the united nations, regional office for asia and the pacific, Bangkok. http://www.fao.org/docrep/014/am626e/am626e00.pdf. Accessed Aug 2012

Sri Lanka: European Commission, United Nations Development Programme, Southeast Asian Regional Center for Graduate Study and Research in Agriculture 2007: Forest Management Through Local Level Action Small Grants Programme for Operations to Promote Tropical Forests (SGPPTF). http://www.searca.org/ptf/temp/docs/SriLanka_CH.pdf. Accessed Aug 2012

Tanzania: Hamza KFS (2007) Tanzania’s forest policy and its practical achievements with respect to community based forest management http://www.metla.fi/hanke/8512/esitelmat-tansania-2007/4-hamza-tnz-forest-policy.pdf

Thang Hooi Chew, James Hewitt, Chen Hin Keong, EU FLEGT Facility Kuala Lumpur January (2012) TIMOR LESTE: Scoping Baseline Information for Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade. www.euflegt.efi.int/files/attachments/euflegt/baseline_study_-_timor_leste.pdf. Accessed Aug 2012

The Forests of the Congo Basin – State of the Forest 2010. Accessed Aug 2012

Timor Leste NFI: http://www.cifap.utad.pt/NFI_Timor.pdf

Uganda: Andrua HJ (2002) Country Paper Uganda. For the fao/ec lnv/gtz workshop on tropical secondary forest management in Africa. http://www.fao.org/docrep/006/J0628E/J0628E65.htm

Vanuatu, Solomon Islands: ASIA-Pacific Forestry Commission 2911. Pacific forests and forestry to 2020. Subregional report of the second asia-pacific forestry sector outlook study. Rap publication 2011/01 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. ISBN 978-92-5-106755-0

Viet Nam: Community Forest Management in Viet Nam. http://www.asiaforestnetwork.org/vie.htm

Zimbabwe: Mufandaedza E (2002) Country Paper Zimbabwe. For the fao/ec lnv/gtz workshop on tropical secondary forest management in Africa. http://www.fao.org/docrep/006/J0628E/J0628E67.htm

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Annex

Annex

Annex 1

See Table 4

Annex 2

See Table 5

Annex 3

See Table 6

Annex 4

See Table 7

Annex 5

See Table 8

Annex 6

See Table 9

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this entry

Cite this entry

Poker, J., MacDicken, K. (2016). Tropical Forest Resources: Facts and Tables. In: Pancel, L., Köhl, M. (eds) Tropical Forestry Handbook. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-54601-3_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-54601-3_7

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-642-54600-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-642-54601-3

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesReference Module Biomedical and Life Sciences