Abstract

Renal lymphoma can present as a primary or secondary manifestation of lymphoma. Both are rare. At imaging studies, five different presentation forms of renal lymphoma can be distinguished: solitary or multiple renal masses, infiltrative lesions, perirenal lymphoma, and extension of a retroperitoneal lymphoid mass in the kidney.

In general, diagnosis of renal lymphoma is not difficult as multisystemic disseminated disease is often present. Biopsy is recommended to avoid surgery. CT and PET-CT remain the modalities of choice for diagnosis and staging. MRI can be useful in patients with iodinated contrast allergy and renal insufficiency. Ultrasound has a role in screening for renal mass in patients with flank pain or renal insufficiency and is the modality of choice in image-guided biopsy.

Renal sarcoma can present as a primary or secondary manifestation of sarcoma. Both are very rare. Diagnosis on imaging is not straightforward because the imaging characteristics are extremely variable, depending on the nature and the degree of differentiation of the tumor components.

There are no pathognomonic signs of a renal sarcoma, and frequently, imaging studies allow no differentiation from other primary epithelial renal parenchymal tumors.

Some signs can suggest the preoperative diagnosis, such as a mass arising from the renal sinus or capsule and the absence of extension of the mass beyond its pseudocapsule. Some subtypes have specific characteristics. Histopathologic analysis is usually essential for the final diagnosis.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Renal Cell Carcinoma

- Synovial Sarcoma

- Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma

- Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma

- Granulocytic Sarcoma

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Renal Lymphoma

1.1 General Features

Extranodal involvement of lymphoma is a common finding, occurring in approximately 40 % of patients with lymphoma (Lee et al. 2008). “Extranodal” refers to sites other than lymph nodes including the spleen, thymus, tonsils, and Waldeyer ring, with the exception of non-Hodgkin’s disease (malignant lymphoma), where the spleen is considered as an extranodal organ.

Every organ or structure can be involved by lymphoma. The kidney is the sixth most affected abdominal site after the spleen, liver, gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, and abdominal wall (Lee et al. 2008). Extranodal involvement is more frequent in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, patients with recurrent disease, and immune-suppressed patients (Guermazi et al. 2001; Leite et al. 2007; Lee et al. 2008). Recognition of extranodal involvement is crucial in initial staging (Cotswold classification, Ann Arbor classification), since it is crucial for prognosis and therapy planning (Guermazi et al. 2001).

Imaging studies have an important role in diagnosis and staging.

1.2 Pathogenesis

Renal lymphoma is divided into primary and secondary forms. The existence of the very rare primary form is still controversial because the kidney does not harbor lymphoid tissue (Kandel et al. 1987; Stallone et al. 2000; Symeonidou et al. 2008).

In fact, renal lymphoma is a diagnosis of exclusion: the disease must be limited to the kidney and adjacent perirenal and perihilar lymph nodes. The pathophysiology of its development is unclear: many theories have been proposed, such as development as a result of chronic inflammatory processes, arising from perinephric lymphoid tissue or from the renal capsule, which is richly embedded in lymph vessels (Pickhardt et al. 2000; Stallone et al. 2000).

More frequently, primary lymphoma is reported in immune-deprived patients and concerns a non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Most patients with primary renal lymphoma quickly develop extrarenal disease, and their prognosis is unfavorable (Kandel et al. 1987).

The more frequent secondary form of lymphoma is caused by hematogenous spread (causing, in general, bilateral involvement) of tumor cells, through sinus, perirenal, or capsular lymphatics or through direct extension from retroperitoneal lymphoma (Leite et al. 2007; Dyer et al. 2008). The most frequent secondary renal lymphoma is found in patients with widespread diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (intermediate and high-grade forms), with Burkitt lymphoma, and with AIDS and in immune-deprived patients.

Symptomatology of renal lymphoma can vary between no symptoms and flank pain, hematuria, night sweat, and fever.

Mortality and morbidity depend on the type and extent of the lymphoma (Zukotynski et al. 2012).

Knowing the pattern of tumor growth and tumor spreading is essential in understanding the presentation of the tumor on imaging. Two patterns of tumor growth are distinguished: the infiltrative type and the expansile type.

In the less frequent infiltrative growth pattern, lymphoma proliferates along the normal interstitial structures, resulting in kidney enlargement and loss of internal architecture with initial preservation of the reniform shape (Pickhardt et al. 2000; Urban and Fishman 2000; Sheth et al. 2006). This appearance is also known as the “faceless kidney” (Zagoria 2004).

Formation of expansile masses is the result of spherical focal tumor proliferation (radial growth pattern), with compression or destruction of the adjacent renal parenchyma and formation of a pseudocapsule (Pickhardt et al. 2000; Urban and Fishman 2000).

1.3 Imaging Features and Differential Diagnosis

Lymphoma has five different appearances on imaging, depending partially on the growth pattern of the tumor: single and multiple masses, perirenal disease, infiltrative disease, and extension of retroperitoneal disease.

1.3.1 Multiple Masses

This is the most frequent presentation pattern of renal lymphoma, seen in 50–60 % of the cases (Jafri et al. 1982; Cohan et al. 1990; Sheth et al. 2006). They present typically bilateral, but unilateral forms have been reported. Size varies from 1 to 4.5 cm (Sheth et al. 2006). Renal contour bulging may be seen in eccentrically located or large masses (Cohan et al. 1990).

On unenhanced CT, the masses may have slightly higher attenuation numbers compared to the surrounding parenchyma; yet sometimes, these masses are hard to detect if no renal contour abnormalities are present. Intravenous contrast administration is indispensable for diagnosis and appropriate staging.

At contrast-enhanced CT, the masses are typically homogeneously hypovascular compared to the surrounding parenchyma, allowing easy detection (Fig. 1).

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in a 76-year-old man. (a) Contrast-enhanced CT in the corticomedullary phase shows multiple hypovascular masses in both kidneys (black arrows). (b) Axial T2-weighted MR image shows a T2-hypointense mass in the upper pole of the left kidney. (c) Diffusion-weighted imaging of this lesion obtained on a b-value of 1000 shows high signal

On MRI, the masses are hypointense on T1-weighted images and iso- or hypointense on T2-weighted images. The characteristics on contrast-enhanced MRI are similar to CT (Sheth et al. 2006).

Large retroperitoneal lymph adenopathies are present in less than 50 % of the cases (Urban and Fishman 2000) and are the key feature for the diagnosis of lymphoma.

In the absence of large retroperitoneal adenopathies, differential diagnosis of bilateral multiple renal lymphoma includes renal metastases and papillary renal cell carcinoma. Clinical history is crucial in the diagnosis, but if there is no known primary malignancy present, biopsy needs to be performed to differentiate between surgical disease and disease processes where surgery must be avoided (Sheth et al. 2006).

From a theoretical point of view, other differential diagnoses include acute pyelonephritis, septic emboli, renal infarcts, and abscesses (Sheth et al. 2006). Their specific radiologic appearance and clinical presentation usually enable the differentiation with lymphoma.

1.3.2 Retroperitoneal Extension

Renal invasion from retroperitoneal extension is the second most frequent presentation pattern and accounts for 25–30 % of the cases (Cohan et al. 1990).

Large confluent retroperitoneal masses encase the renal vasculature and invade the renal hilum with occasionally mild secondary hydronephrosis (Urban and Fishman 2000; Sheth et al. 2006; Leite et al. 2007; Symeonidou et al. 2008) (Fig. 2).

Follicular lymphoma in a 71-year-old man. Contrast-enhanced CT in the parenchymal phase shows a large hypovascular retroperitoneal mass extending into the renal hilum with encasement of the left renal vessels (arrow) and involving the kidney resulting in a hypoattenuating enlarged left kidney. Hydronephrosis is absent

Occlusion or thrombosis of renal veins and arteries is rare despite the, at times, massive tumor burden (Urban and Fishman 2000; Sheth et al. 2006). Lateral displacement of the kidney is not infrequent.

Bulky lymphadenopathies can be seen in other tumors, even with extension into the kidney. Differential diagnosis is based on the aspect of the adenopathies, which tend to be softer in lymphoma. Lymphoma adenopathies encase vascular structures, whereas adenopathies from other primaries obstruct and invade vascular structures (Urban and Fishman 2000).

1.3.3 Infiltrative Disease

Infiltrative renal involvement presents as nephromegaly with disruption of the internal architecture and preservation of renal shape (Fig. 3). It occurs generally bilateral and is more commonly seen in Burkitt lymphoma (Sheth et al. 2006). It is observed in 20 % of patients with renal lymphoma (Reznek et al. 1990).

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (immunomodulator agent-related lymphoproliferative disorder) in a 75-year-old woman. (a) Contrast-enhanced CT in the parenchymal phase shows an infiltrative hypovascular mass in the upper pole of the left kidney with discrete infiltration of the perirenal fat (arrow). (b) Coronal image shows diffuse pericardial involvement (arrow)

Intravenous contrast administration is essential to appreciate the enhancement characteristics, the focal ill-defined hypovascular areas, and the loss of corticomedullary differentiation secondary to the infiltrative growth pattern. Encasement of the renal collecting system is often present.

Renal function is frequently moderately impaired.

Certainly, when this presentation is unilateral, the differential diagnosis includes other tumoral disease processes (renal cell carcinoma, medullary tumors, transitional and squamous cell carcinoma, renal sarcoma, leukemia, plasmocytoma, metastases, and infiltrative pediatric tumors) and inflammatory diseases (bacterial and xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis, renal parenchymal malacoplakia) with a predominately infiltrative pattern (Pickhardt et al. 2000).

1.3.4 Solitary Mass

A solitary mass is found in 10–20 % of the cases (Cohan et al. 1990; Reznek et al. 1990). Solitary masses exhibit similar imaging characteristics as the multiple masses (Fig. 4). Solitary masses can be as large as 15 cm (Reznek et al. 1990).

Differential diagnosis with other solitary renal masses such as renal carcinoma has to be included, yet, the majority of renal cell carcinomas show hypervascular and heterogeneous enhancement. The presence of vascular invasion is also almost exclusively seen in renal cell carcinoma. Retroperitoneal adenopathy can be present in both cases, but tend to be much larger and confluent in lymphoma (Urban and Fishman 2000).

1.3.5 Perirenal Disease

Perirenal involvement is usually a part of retroperitoneal extension.

Isolated perirenal disease is very unusual (<10 % of cases of perirenal lymphoma) and appears as a soft tissue mass involving the perirenal space partially or completely and compresses but not invades the kidney (Bechtold et al. 1996; Leite et al. 2007; Surabhi et al. 2008) (Fig. 5). The presentation of perirenal soft tissue mass without renal invasion and functional impairment is almost pathognomonic (Sheeran and Sussman 1998; Urban and Fishman 2000; Sheth et al. 2006). To differentiate the perirenal soft tissue mass from the underlying parenchyma, contrast administration is crucial.

Findings can yet be more limited to plaques and nodules in the perirenal space and thickening of Gerota’s fascia (Sheeran and Sussman 1998). These limited findings can cause a diagnostic problem since benign (perinephric hematoma, urinoma, extramedullary hematopoiesis, fibrosis, amyloidosis) and malignant conditions (sarcoma, metastases, primary renal carcinoma) can cause minimal changes in the perirenal space (Urban and Fishman 2000; Sheth et al. 2006). Clinical history and secondary findings can help in further differentiation.

1.3.6 Atypical Findings

Although very unusual, atypical findings may be observed in each presentation form including calcification, necrosis, spontaneous hemorrhage, cyst formation, and heterogeneous enhancement (Heiken et al. 1983).

Heterogeneous or cystic appearance is rare and seen in larger masses and masses with tumor necrosis in the context of chemotherapy (Urban and Fishman 2000; Sheth et al. 2006).

1.4 Role of Different Imaging Modalities

1.4.1 Ultrasound

Ultrasound is widely accepted as the screening modality for renal mass lesions in patients with flank pain and functional renal impairment. Contrast-enhanced CT and MRI are superior to ultrasound in diagnosis (higher sensitivity and specificity) and in evaluating the extent of disease.

Ultrasound has a role in guiding percutaneous biopsies (Tornroth et al. 2003; Sheth et al. 2006) and is recommended because of the absence of radiation.

1.4.2 Computed Tomography and Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography (PET-CT)

Contrast-enhanced multidetector CT and PET-CT are the golden standard in detection, staging, and follow-up of lymphoma.

All presentation forms of renal lymphoma tend to be hypovascular and generally show a homogeneous enhancement. For optimal lesion detection, the CT must be performed in the nephrographic or parenchymal (venous) phase. In the venous phase, the cortex and medulla enhance equivocally, and the risk of missing medullar lesions is minimized. Unenhanced CT can be performed prior to contrast administration to objectivate the lesion enhancement.

Corticomedullary or arterial phase is useful only in examining vascular involvement and excretory phase in examining collecting system involvement.

CT further enables the evaluation of disease extension in adjacent structures and detection of other sites of nodal and extranodal involvement. This is important in initial staging and follow-up, because of the impact on therapy and prognosis.

In this respect, CT/PET-CT scan needs to be combined with thoracic and/or neck CT scan.

PET is more sensitive and specific than CT in detecting small tumor deposits (Moog et al. 1998). Attention should be paid to lesions adjacent to the hilum because they could be masked by FDG in the urine (Zukotynski et al. 2012).

Combination of PET and CT combines the advantages of both techniques and at present has become routine in disease follow-up.

CT can also be used in guiding percutaneous biopsy for lesions difficult to access with ultrasound.

1.4.3 MRI

On MRI, the lymphoid masses are like most renal masses, hypointense on T1-weighted images and iso- or hypointense on T2-weighted images. There is moderate enhancement on enhanced MRI.

Results in literature show that the MRI is equally reliable as CT in detection and characterization of lymphoid lesions (Lowe et al. 2000; Sheth et al. 2006).

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) may show restricted diffusion due to the high cellularity of a lymphoma. ADC ranges of 0,64–0,76 (×10−3 mm2/s) were suggested for a lymphoma in two separate studies (Wu et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2013).

Despite these good results, CT remains the golden standard because of its cost-effectiveness, ability to evaluate the chest, and availability.

MRI is useful in patients with iodinated contrast allergy or renal insufficiency (Sheth et al. 2006). MRI has perspectives in future for the evaluation of bone marrow involvement.

1.5 Diagnostic Approach

Usually, the radiologic image is sufficient to establish the diagnosis of renal lymphoma. In most cases, the diagnosis is already known before imaging, due to nodal biopsy at initial presentation.

When a renal lesion has characteristics suggesting renal lymphoma, image-guided biopsy is recommended for diagnosis and further therapeutic management (Sheth et al. 2006).

2 Renal Sarcoma

2.1 General Features

Two subtypes are discriminated: primary and secondary sarcoma. The secondary form is further subdivided into renal metastases or direct extension of a retroperitoneal sarcoma. The secondary subgroup is more frequent (Pickhardt et al. 2000). The sarcomatoid type of RCC is not included.

Renal metastases from sarcoma are very rare and are often dependent on the location of the primary lesion. Extremity sarcomas tend to spread to the lungs, whereas retroperitoneal and gastrointestinal sarcomas often spread to the liver (Greene et al. 2006).

Primary renal sarcoma is a very rare presentation form of sarcoma. 1.1 % of malignant renal tumors are sarcomas (Jenkins et al. 1971; Shirkhoda and Lewis 1987; Prasad et al. 2005).

Renal sarcoma affects patients in their fourth to seventh decades, with a slight male preponderance.

Patients often present with an abdominal mass, flank pain, hematuria, and sometimes weight loss. Occasionally, renal sarcoma is an incidental finding (Shirkhoda and Lewis 1987).

Sarcomas have high rates of local recurrence and metastases, and the prognosis is poor (Shirkhoda and Lewis 1987; Prasad et al. 2005). Invasive surgery and chemotherapy are usually indispensable.

2.2 Pathogenesis

Each type of mesenchymal cell in the kidney can develop into a different histological type of sarcoma. About 11 histological subtypes are distinguished: liposarcoma, hemangiopericytoma, angiosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma (ES), osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and synovial sarcoma.

Leiomyosarcoma is considered to be the most frequent type of renal sarcoma and accounts for about 50 % of the renal sarcomas. Liposarcoma and fibrosarcoma are also more frequently encountered (Shirkhoda and Lewis 1987; Pickhardt et al. 2000).

2.3 Imaging Features

Again, two growth patterns are seen in sarcoma: the expansile and the infiltrative growth pattern. Rhabdomyosarcoma and angiosarcoma present more often as an infiltrative lesion, leiomyosarcoma and the other sarcoma subtypes more often as an expansile mass (Pickhardt et al. 2000).

Imaging is variable and depends on the nature and the degree of differentiation of the tumor components. Sarcomas are rapid-growing, large tumors, but these are not specific features enabling the diagnosis. In general, renal sarcomas cannot be differentiated from renal cell carcinomas on imaging.

Some signs can suggest a preoperative diagnosis such as a mass that arises from the renal sinus or capsule, the absence of extension of the mass beyond its pseudocapsule, the highly vascularized areas, and the areas of necrosis (Shirkhoda and Lewis 1987). Some subtypes have specific characteristics.

The MRI appearance of renal sarcomas is rarely discussed in current literature. Sarcomas tend to be of intermediate to hypointense signal intensity on T1-weighted MR imaging and of intermediate to hyperintense signal intensity on T2-weighted MR imaging (Billingsley and Restrepo 2006).

2.3.1 Liposarcoma

Liposarcoma is the most common retroperitoneal malignant tumor (Surabhi et al. 2008). It arises from nonfat-containing areas in the kidney such as the capsule and rarely the parenchyma (Shirkhoda and Lewis 1987).

Their imaging appearance is strongly dependent on their histological subtype (well-differentiated, myxoid, round cell, pleomorphic, and dedifferentiated subtypes).

Well-differentiated liposarcomas contain mainly macroscopic fat. Round cell and pleomorphic liposarcomas present as a soft tissue mass; the myxoid type has a cystic appearance, while dedifferentiated liposarcomas can present intralesional calcifications or ossifications (Fig. 10) (Secil et al. 2005; Surabhi et al. 2008). Liposarcomas tend to be hypovascular.

Differential diagnosis of angiomyolipoma with liposarcoma can be difficult if the angiomyolipomas are large and exophytic. The presence of large intratumoral vessels, intralesional hemorrhage, sharp parenchymal defect, and associated angiomyolipomas favors the diagnosis of an angiomyolipoma (Wang et al. 2002; Israel et al. 2002).

2.3.2 Hemangiopericytoma and Angiosarcoma

A hemangiopericytoma is a soft tissue vascular tumor that originates from the Zimmerman pericytes. On imaging, it presents as a large, lobulated, well-defined, hypervascular mass, usually with necrotic areas and calcifications. Differential diagnosis with renal cell carcinoma is difficult. Hemangiopericytoma often occurs in younger patients (fourth decade) than renal cell carcinoma (Brescia et al. 2008; Surabhi et al. 2008).

Angiosarcoma is a rare tumor that arises from endothelial cells. Renal involvement is mostly the result of metastases from primary dermal or visceral angiosarcoma. On imaging, it presents as a heterogeneous hypervascular infiltrative mass. Sometimes, hemorrhage can be observed on unenhanced CT or MRI. Calcification can be present. The role of carcinogens (arsenic, thorium dioxide, vinyl chloride exposure) as in hepatic angiosarcoma has not been established in renal angiosarcoma (Leggio et al. 2006; Yu et al. 2008).

2.3.3 Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma and Fibrosarcoma

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma is extremely rare and arises from primitive mesenchymal cells which demonstrate both histiocytic and fibroblastic differentiation. The age at presentation ranges from the fifth to seventh decades. There is no sex predilection (Kwak et al. 2003; Surabhi et al. 2008; Kim et al. 2012). They present as a large heterogeneous mass with areas of necrosis, hemorrhage, and local invasion (Kwak et al. 2003; Surabhi et al. 2008). Calcification or ossification can also be present (Secil et al. 2005). At MR imaging the mass is isointense on T1 and heterogeneously hyperintense on T2 (Kim et al. 2012).

Fibrosarcoma is thought to originate from the connective tissue in the renal capsule. There is no sex predilection. It usually occurs in patients older than 40 years. Prognosis is poor with a 5-year survival rate of 10 % (Katabathina et al. 2010).

On imaging, the tumor usually presents as a large, encapsulated, and hypovascular mass, but cannot be differentiated from leiomyosarcoma and (sarcomatoid) RCC. It can be differentiated only on immunohistochemical staining of appropriate biopsies. Invasion of the renal vein is seen in about 40 % of the cases (Kansara and Powell 1980; Shirkhoda and Lewis 1987; Agarwal et al. 2008).

2.3.4 Leiomyosarcoma and Rhabdomyosarcoma

Leiomyosarcoma (Fig. 6) is the most frequent subtype of renal sarcoma. It arises from the smooth muscle cells in the inner layer of the renal capsule, from the smooth muscle cells in the tunica media of small vessels in the renal parenchyma or of the large renal vessels (renal vein), or from the smooth muscle cells in the renal pelvis wall. Sometimes, leiomyosarcomas are the result of malignant transformation of an angiomyolipoma (Lowe et al. 1992).

The patients with a leiomyosarcoma tend to be between 40 and 70 years of age. There is no sex predilection. Prognosis is poor with a 5-year survival rate of 29–36 % (Katabathina et al. 2010).

On unenhanced CT, leiomyosarcomas are often hyperattenuating compared to the renal parenchyma and have almost equal attenuation values as the lumbar musculature. Tumor calcification is present in about 10 % of the cases. Spontaneous ruptures have been reported (Billingsley and Restrepo 2006). Large leiomyosarcomas tend to show central necrotic areas (Katabathina et al. 2010).

Leiomyosarcomas tend to be hypovascular on imaging, but exceptions have been reported. It is difficult to differentiate leiomyosarcoma with the benign renal leiomyoma. Most frequently, renal leiomyomas are well encapsulated, small cortical tumors of less than 2 cm, and originate most commonly from the renal capsule. Frequently, a plane is distinguishable between the tumor and the kidney without parenchymal distortion. Leiomyosarcomas are larger and less encapsulated, but sometimes, they have almost similar imaging characteristics as their benign counterpart. In that case, biopsy can be indispensable to obtain preoperative diagnosis (Roy et al. 1998).

Renal rhabdomyosarcoma arises from the embryonal mesenchyme that ultimately develops into striated skeletal muscle (Sola et al. 2007). It is generally found in young patients and rarely in adults. Rhabdoid tumor of the kidney is considered as a different entity (Schmidt et al. 1982; Agrons et al. 1997). In literature, no specific imaging features have been assigned to renal rhabdomyosarcoma.

2.3.5 Osteosarcoma, Chondrosarcoma, Ewing Sarcoma, and Synovial Sarcoma

Renal osteosarcoma is believed to originate from undifferentiated renal mesenchymal cells.

Extraskeletal primary osteosarcoma is a rare aggressive tumor and accounts for 4 % of osteosarcomas. The most frequent locations of extraskeletal osteosarcomas are the lower and upper extremities and retroperitoneum. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma occurs in older patients (fourth to sixth decade) than osteogenic osteosarcoma (Secil et al. 2005). Prognosis is extremely poor (Katabathina et al. 2010).

Imaging shows extensive intralesional ossification or calcification in a “sunburst” pattern (Fig. 7). This can be seen on plain abdominal radiography (O’Malley et al. 1991). The mass can show a variable grade of mineralization, but the calcification is frequently intense and amorphous. The non-mineralized areas have an attenuation that resembles muscle on CT scan and intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images (Secil et al. 2005). Renal osteosarcomas are frequently hypervascular.

(a–c) Renal osteosarcoma in a 51-year-old woman. Axial (a) and coronal (b, c) images of a contrast-enhanced CT in the parenchymal phase show a large heterogeneous infiltrative mass occupying the left kidney with extensive intralesional calcification in a “sunburst” pattern. This mass infiltrates the kidney, with partial preservation of its bean-shaped configuration (curvilinear line form). On the other hand, the tumor also shows an expansile growth pattern with extension beyond Gerota’s fascia (arrowhead). The tumor also extends in the renal sinus with calcified tumor thrombosis in the renal vein (arrow). Large heterogeneous/necrotic adenopathies are depicted in the left para-aortic region (curved arrow)

Extensive intralesional ossification or calcification can also be seen in sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma and metastatic lesion of osteogenic sarcoma (Micolonghi et al. 1984). Other renal sarcomas such as malignant fibrous histiocytoma and dedifferentiated liposarcoma can also undergo extensive calcification or ossification (Secil et al. 2005).

Renal chondrosarcoma is believed to originate from undifferentiated renal mesenchymal cells.

Extraskeletal chondrosarcoma occurs in young patients (second and third decade) with a female preponderance (Gomez-Brouchet et al. 2001).

The most frequent locations of extraskeletal chondrosarcoma are the brain, meninges, neck, trunk, retroperitoneum, and extremities (Malhotra et al. 1984).

They are generally slow-growing tumors, but late metastases can occur.

Imaging shows a large soft tissue mass with central calcification (Nativ et al. 1985).

Renal Ewing sarcoma (ES) and primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) are considered in the WHO classification as one entity with a spectrum of differentiation (Ushigome et al. 2002).

Renal ES-PNET is supposed to originate from the neural cells in the kidney or the embryonic neural crest cells that migrate into the kidney (Clapp and Croker 1997).

Primary renal ES-PNET occurs more frequently in adolescents and young adults. They are aggressive tumors with invasion into the surrounding structures (renal vasculature, spine) and early metastases to the regional lymph nodes, bone, lung, and liver (Chu et al. 2008).

Imaging shows large heterogeneous tumors with sometimes ill-defined margins (Pickhardt et al. 2000). Figure 8 shows solitary renal metastasis of a primary Ewing sarcoma of the pelvic bone.

(a–c) Renal metastasis of a pelvic Ewing sarcoma in a 26-year-old woman. (a) Axial contrast-enhanced CT in the parenchymal phase shows a well-circumscribed, heterogeneous, extensively calcified mass posterolateral in the inferior pole of the left kidney. (b) The mass lies in close relation with the anterior (arrowhead) and posterior renal fascia (arrow), which appear thickened. Note the thickening of the lateroconal fascia (curved arrow). (c) Primary site of the Ewing sarcoma in the right pelvic bone appearing as extended heterogeneous zones of osteolysis (arrow)

Renal synovial sarcoma is a very rare tumor. Most often this spindle cell malignant tumor occurs in the extremities of adolescents and young adults. Primary synovial sarcoma of the kidney was first reported in 1999 (Faria et al. 1999; (Katabathina et al. 2010). The knowledge about this type of sarcoma is limited as few case reports were published. Prognosis is extremely poor.

CT shows a heterogeneous enhancing tumor with solid and cystic components (Fig. 9) (Erturhan et al. 2008; Mirza et al. 2008). At MR imaging, the lesion is heterogeneously T2 hyperintense and T1 hypointense with areas of hemorrhage, fluid levels, and septation (Katabathina et al. 2010).

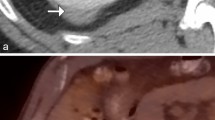

(a–e) Monophasic renal synovial sarcoma in a 47-year-old man. (a) Ultrasound shows a heterogeneous, partially cystic mass in the left renal sinus (arrow) with retro-acoustic intensification. Hydronephrosis is absent. MRI of the kidney was performed. (b) Coronal T2-weighted imaging and (c) axial late T2-weighted imaging show a left renal sinus mass with central T2-hypointense nodular component (arrow) and peripheral T2-hyperintense cystic component (curved arrow). (d) Axial T1-weighted imaging with fat saturation before contrast administration shows that the lesion has a mixed hyper- and hypointense signal intensity. (e) Contrast-enhanced axial T1-weighted imaging with fat saturation in the parenchymal phase shows an enhancing nodular soft tissue component anteriorly in the lesion (arrow)

2.3.6 Granulocytic Sarcomas (Chloromas)

Granulocytic sarcomas (chloromas) are rare malignant tumors of granulocytic precursors that can present in up to 10 % of patients with acute myelogenous leukemia and rarely in acute lymphocytic leukemia.

In imaging, they present as focal hypovascular soft tissue masses in one or both kidneys (Surabhi et al. 2008).

2.3.7 Kaposi Sarcoma

Kaposi sarcoma originates from the blood and lymphatic vessels.

Kaposi usually affects the skin but can affect variable thoracic and abdominal organs.

It was a very uncommon type of tumor till the beginning of the AIDS epidemic.

Renal AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma has been observed in autopsy reports but rarely shows clinical or radiologic manifestations (Restrepo et al. 2006).

2.4 Diagnostic Approach

If a large encapsulated renal mass with aggressive growth pattern arises from the renal sinus or capsule, renal sarcoma must be enclosed in your differential diagnostic list. Because of the lack of specific signs and high resemblance with the more frequent RCC, final diagnosis is usually made on histopathologic analysis.

References

Agarwal K, Singh S, Pathania OP (2008) Primary renal fibrosarcoma: a rare case report and review of literature. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 51:409–410

Agrons GA, Kingsman KD, Wagner BJ et al (1997) Rhabdoid tumor of the kidney in children: a comparative study of 21 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol 168:447–451

Bechtold RE, Dyer RB, Zagoria RJ et al (1996) The perirenal space: relationship of pathologic processes to normal retroperitoneal anatomy. Radiographics 16:841–854

Billingsley ED, Restrepo S (2006) Kidney sarcomas. In: Guermazi A (ed) Imaging in kidney cancer. Springer, Berlin, pp 145–157

Brescia A, Pinto F, Gardi M et al (2008) Renal hemangiopericytoma: case report and review of the literature. Urology 71:755.e9–755.e12

Chu WC, Reznikov B, Lee EY et al (2008) Primitive neuroectodermal tumour (PNET) of the kidney: a rare renal tumour in adolescents with seemingly characteristic radiological features. Pediatr Radiol 38:1089–1094

Clapp WL, Croker BP (1997) Adult kidney. In: Sternberg S (ed) Histology for pathologists, 2nd edn. Raven, New York, pp 799–834

Cohan RH, Dunnick NR, Leder RA et al (1990) Computed tomography of renal lymphoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr 4:933–938

Dyer R, DiSantis DJ, McClennan BL (2008) Simplified imaging approach for evaluation of the solid renal mass in adults. Radiology 247:331–343

Erturhan S, Seçkiner I, Zincirkeser S et al (2008) Primary synovial sarcoma of the kidney: use of PET/CT in diagnosis and follow-up. Ann Nucl Med 22:225–229

Faria P, Argani P, Epstein J (1999) Primary synovial sarcoma of the kidney: a molecular subset of so-called embryonal renal sarcoma. Mod Pathol 12:94A

Gomez-Brouchet A, Soulie M, Delisle MB et al (2001) Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma of the kidney. J Urol 166:2305

Greene FL, Compton CC, Fritz AG et al (2006) AJCC cancer staging atlas. Springer, New York, pp 191–194

Guermazi A, Brice P, de Kerviler E et al (2001) Extranodal Hodgkin disease: spectrum of disease. Radiographics 21:161–179

Heiken JP, Gold RP, Schnur MJ et al (1983) Computed tomography of renal lymphoma with ultrasound correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr 7:245–250

Israel GM, Bosniak MA, Slywotzky CM et al (2002) CT differentiation of large exophytic renal angiomyolipomas and perirenal liposarcomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol 179:769–773

Jafri SZ, Bree RL, Amendola MA et al (1982) CT of renal and perirenal non-Hodgkin lymphoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 138:1101–1105

Jenkins JD, Anderson CK, Williams RE (1971) Renal sarcoma. Br J Urol 43:263–267

Kandel LB, McCullough DL, Harrison LH et al (1987) Primary renal lymphoma. Does it exist? Cancer 60:386–391

Kansara V, Powell I (1980) Fibrosarcoma of the kidney. Urology 26:419–421

Katabathina VS, Vikram R, Nagar AM et al (2010) Mesenchymal neoplasms of the kidney in adults: imaging spectrum with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 30:1525–1540

Kim KH, Lee SH, Cha SH et al (2012) Malignant fibrous histiocytoma arising from a hydronephrotic kidney: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Imaging 36:239–242

Kwak HS, Kim CS, Lee JM (2003) MR findings of renal malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Eur Radiol 13(suppl 6):L245–L246

Lee WK, Lau EW, Duddalwar VA et al (2008) Abdominal manifestations of extranodal lymphoma: spectrum of imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 191:198–206

Leggio L, Addolorato G, Abenavoli L et al (2006) Primary renal angiosarcoma: a rare malignancy. A case report and review of the literature. Urol Oncol 24:307–312

Leite NP, Kased N, Hanna RFB et al (2007) Cross-sectional imaging of extranodal involvement in abdominopelvic lymphoproliferative malignancies. Radiographics 27:1613–1634

Lowe BA, Brewer J, Houghton DC et al (1992) Malignant transformation of angiomyolipoma. J Urol 147:1356–1358

Lowe LH, Isuani BH, Heller RM et al (2000) Pediatric renal masses: Wilms tumor and beyond. Radiographics 20:1585–1603

Malhotra CM, Doolittle CH, Rodil JV et al (1984) Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma of the kidney. Cancer 54:2495–2499

Micolonghi TS, Liang D, Schwartz S (1984) Primary osteogenic sarcoma of the kidney. J Urol 131:1164–1166

Mirza M, Zamilpa I, Bunning J (2008) Primary renal synovial sarcoma. Urology 72:716.e11–716.e12

Moog F, Bangerter M, Diederichs CG et al (1998) Extranodal malignant lymphoma: detection with FDG PET versus CT. Radiology 206:475–481

Nativ O, Horowitz A, Lindner A et al (1985) Primary chondrosarcoma of the kidney. J Urol 134:120–121

O’Malley FP, Grignon DJ, Shepherd RR et al (1991) Primary osteosarcoma of the kidney. Report of case studies by immunohistochemistry, electron microscopy and DNA flow cytometry. Arch Pathol Lab Med 115:1262–1265

Pickhardt PJ, Lonergan GJ, Davis CJ Jr et al (2000) From the archives of the AFIP. Infiltrative renal lesions: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. Radiographics 20:215–243

Prasad SR, Humphrey PA, Menias CO et al (2005) Neoplasms of the renal medulla: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 25:369–380

Restrepo CS, Martinez S, Lemos JA et al (2006) Imaging manifestations of Kaposi sarcoma. Radiographics 26:1169–1185

Reznek RH, Mootoosamy I, Webb JA et al (1990) CT in renal and perirenal lymphoma: a further look. Clin Radiol 42(233):238, Erratum in: Clin Radiol 43(4):289

Roy C, Pfleger D, Tuchmann C et al (1998) Small leiomyosarcoma of the renal capsule: CT findings. Eur Radiol 8:224–227

Schmidt D, Harms D, Zieger G (1982) Malignant rhabdoid tumor of the kidney. Histopathology, ultrastructure and comments on differential diagnosis. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 398:101–108

Secil M, Mungan U, Yorukoglu K et al (2005) Case 89: retroperitoneal extraskeletal osteosarcoma. Radiology 237:880–883

Sheeran SR, Sussman SK (1998) Renal lymphoma: spectrum of CT findings and potential mimics. AJR Am J Roentgenol 171:1067–1072

Sheth S, Ali S, Fishman E (2006) Imaging of renal lymphoma: patterns of disease with pathologic correlation. Radiographics 26:1151–1168

Shirkhoda A, Lewis E (1987) Renal sarcoma and sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma: CT and angiographic features. Radiology 162:353–357

Sola JE, Cova D, Casillas J et al (2007) Primary renal botryoid rhabdomyosarcoma: diagnosis and outcome. J Pediatr Surg 42:e17–e20

Stallone G, Infante B, Manno C et al (2000) Primary renal lymphoma does exist: case report and review of the literature. J Nephrol 13:367–372

Surabhi VR, Menias C, Prasad SR et al (2008) Neoplastic and non-neoplastic proliferative disorders of the perirenal space: cross-sectional imaging findings. Radiographics 28:1005–1017

Symeonidou C, Standish R, Sahdev A et al (2008) Imaging and histopathologic features of HIV-related renal disease. Radiographics 28:1339–1354

Törnroth T, Heiro M, Marcussen N et al (2003) Lymphomas diagnosed by percutaneous kidney biopsy. Am J Kidney Dis 42:960–971

Urban BA, Fishman EK (2000) Renal lymphoma: CT patterns with emphasis on helical CT. Radiographics 20:197–212

Ushigome S, Machinami R, Sorensen PH (2002) World Health Organization classification of tumours: pathology and genetics: tumours of soft tissue and bone. IARC Press, Lyon, pp 298–300

Wang LJ, Wong YC, Chen CJ et al (2002) Computerized tomography characteristics that differentiate angiomyolipomas from liposarcomas in the perinephric space. J Urol 167:490–493

Wu X, Pertovaara H, Dastidar P et al (2013) ADC measurements in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma: a DWI and cellularity study. Eur J Radiol 82:158–164

Yu RS, Chen Y, Jiang B et al (2008) Primary hepatic sarcomas: CT findings. Eur Radiol 18:2196–2205

Zagoria RJ (2004) Renal masses. In: James H. Thrall (ed) Genitourinary radiology: the requisites, 2nd edn. Mosby, Philadelphia, pp 115–118

Zhang Y, Chen J, Shen J et al (2013) Apparent diffusion coefficient values of necrotic and solid portion of lymph nodes: differential diagnostic value in cervical lymphadenopathy. Clin Radiol 68:224–231

Zukotynski K, Lewis A, O’Regan K et al (2012) PET/CT and renal pathology: a blind spot for radiologists? Part 2-Lymphoma, leukemia and metastatic disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 199:W163–W167

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rappaport, A., Oyen, R.H. (2014). Renal Lymphoma and Renal Sarcoma. In: Quaia, E. (eds) Radiological Imaging of the Kidney. Medical Radiology(). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-54047-9_25

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-54047-9_25

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-642-54046-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-642-54047-9

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)