Abstract

Emerging economies are characterized by a reduced level of transparency and accountability of their business environment. Previous research on corporate governance practices in these economies has highlighted the difficulties of implementing corporate governance codes, the reduced level of compliance with these codes and the reluctance of local businesses to change the manner in which they are managed. In this context, multinational corporations (MNCs) are often perceived as “knowledge transfer” agents contributing to the improvement of local practices. However, the transfer is not unilateral, but it should be rather seen as a process of mutual transformation and adaptation. The aim of this chapter is to investigate the role of multinationals in improving corporate governance practices in emerging economies. We conduct a case study on the privatization of Petrom, the largest company listed on the Romania's Bucharest Stock Exchange (BSE). The case suggests that the alignment of Petrom’s practices with the new owner’s (Austrian company OMV) vision and strategy, besides contributing to superior performance and accountability of the company itself, led to a significant improvement of the local corporate governance. This is a story of successful privatization which sheds light on the mechanisms of globalization and on how economic progress is obtained.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Corporate Governance

- Annual Report

- Enterprise Resource Planning System

- Corporate Governance Mechanism

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

Despite an increasing body of literature, corporate governance remains understudied in emerging economies. The interest of this case study is justified by the richness of the East-European field. First, this is induced by the variations between countries and even between firms within the same country in adopting good practices (Przbyłowski et al. 2011), and second, by the multiplicity of factors influencing the output of reforms, such as local traditions and regulations (Przybyłowski et al. 2011), informal rules (Boytsun et al. 2011), and general economic change (Megginson and Netter 2001). While initially post-communist economies had similar institutional structure (the command economy), reforms and institutional transformations produced a variety of outcomes (Mickiewicz 2009).

Companies in these economies needed improvements of their governance systems in order to successfully adapt to a market economy. Privatization was one of the means of triggering or supporting these changes. Previous findings suggest a large variation of outcomes of the privatization process, especially in emerging economies (Gołębiowska-Tataj and Klonowski 2009; Omran 2009; Denisova et al. 2012). Issues related to the legitimacy of the privatization process (Denisova et al. 2012), the local rules and regulations (Young 2010) and to firms’ characteristics (Black et al. 2012) are put forward in order to explain the variety of privatization’s outcomes. However, the manner in which Western practices are transferred (Ezzamel and Xiao 2011), the evolution of corporate governance practices within the local context and the role of privatization in this process (Megginson and Netter 2001) are still insufficiently explored.

The aim of this chapter is to investigate the role of multinationals in improving corporate governance practices in emerging economies,Footnote 1 in the context of the privatization of a company based in an ex-communist country. We conduct a case study on Petrom, the biggest oil company in Central and Eastern Europe and the largest company listed on the BSE. Petrom’s privatization took place in 2004, when the Romanian Government sold the controlling interest in the company to the Austrian group OMV. While it was at times viewed as a controversial privatization, with political implications and conflicting public opinions, Petrom is now considered to be a successful company, a model of best practices, and embracing such values as ethics, respect, corporate citizenship and a viable management strategy. The case study method was preferred as it allows an in-depth analysis of improvements and transformations undergone by Petrom after its privatization. Additionally, this case is an opportunity to discuss how global corporate governance models and practices are transferred and implemented in an entity, and how this transfer contributes to enhancing cross-national cooperation and co-ordination.

Our case study suggests that the alignment of Petrom’s practices with OMV’s practices and strategy, besides contributing to a superior performance and accountability of the company itself, led to significant improvement of the local corporate governance. As such, this case may constitute a model for other local companies while shedding light on the mechanisms of globalization and economic progress. The transfer of knowledge and practices is not unilateral, but it should be seen rather as a process of mutual transformation and adaptation, as MNCs have to take into account the local context, the local cultural and societal codes. Thus, transitional European countries and MNCs are somehow shaping each other, and in this process they are also shaping and challenging the concept of corporate governance. These results contribute to an emerging literature concerned with how global models and standardization projects interact with the local institutions and practices (Megginson and Netter 2001; Mennicken 2008; Gołębiowska-Tataj and Klonowski 2009; Ezzamel and Xiao 2011).

As privatizations and knowledge transfers from multinationals are still on going in many countries, this study is both relevant and timely, and our results might be of interest to investors, policy makers and other researchers in this area.

The remainder of this chapter is organized as follows: after a literature review on the privatization effects in emerging economies and the role of multinationals, the research methodology is presented. A detailed analysis of the case follows, and the results and conclusion close the chapter.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Privatizations and Corporate Governance in Emerging Economies

Corporate governance is viewed as a set of institutional and market-based mechanisms used to reduce agency costs (Omran 2009), or to improve information flows and increase accountability (Dyck 2001). Corporate governance mechanisms became important in emerging economies, especially in ex-communist ones, where the market-based orientation emerged as a necessity in the business environment. However, difficulties appeared when changes had to be implemented in companies that were used to function in a centralized system.

Most local managers in such countries were found to have communist ideological legacies, little competence and determination to make changes in line with the market-based economy model (Young 2010). Corporate governance systems were absent or very weak immediately after the fall of communism, and sometimes even considered undesirable (Earle and Sapatoru 1994). Djankov and Murrell (2002) find that new entrepreneurial management was implemented in order to generate improvements in the business environment. Privatizations represented another means. Besides the need to promote economic efficiency, privatizations raised revenue for the state and introduced competition (Megginson and Netter 2001).

A variety of privatization strategies was employed in emerging economies, ranging from mass privatization, the creation of private ownership funds, direct sales to domestic and foreign investors, and public offerings (Earle and Sapatoru 1994). However, changes were slow, at least in some countries, and transition took more than a decade. Besides privatization programs, there were legislation changes and alignment with international standards was visible, at least after 2000. In this regulatory framework, corporate governance became an important topic as privatizations stimulated reflection on how entities should be owned and controlled, showing the need for sound rules and practices in order to protect and encourage foreign investment (Becht et al. 2005).

However, the outcomes of these changes varied in emerging economies (Omran 2009; Denisova et al. 2012). On the one hand, corporate governance systems are the result of “the effects of legal systems, business practices, institutions, and past histories of countries” (Costello and Costello 2004, p. 8) and therefore the change process is neither linear nor predictable. On the other hand, imported practices or rules may not lead to the intended outcome because corporate governance models are institution and firm-specific (Boytsun et al. 2011; Black et al. 2012).

Prior research investigated the impact of several factors on the outcome of the privatization process, as well as the effects of governance mechanisms. Some studies suggest that ownership identity, in particular foreign and strategic investors, have a positive impact on firms’ performance (Claessens et al. 1997; Dyck 2001; Djankov and Murrell 2002; Omran 2009). Moreover, the existence of foreign owners is a strong indicator of restructuring (Dyck 2001; Djankov and Murrell 2002). Djankov and Murrell (2002) consider that a successful privatization should result in increased efficiency, profitability, and stronger financial health. A positive impact of corporate governance good practices on performance is also assumed (Black et al. 2012; Gołębiowska-Tataj and Klonowski 2009; Djankov and Murrell 2002). The outcomes of the privatization process, may range from no impact on performance to significant improvements (Omran 2009). Also, there are variations in the manner in which organizations respond to change pressures and restructuring plans (Djankov and Murrell 2002). Gołębiowska-Tataj and Klonowski (2009) illustrates how the participation of Western partners in an entity from Poland did not result in improvements in practices and performance, but in ignoring corporate governance principles.

In conclusion, existing literature provides a limited understanding of the changes generated by privatization and their interrelation with changes in the local business environment. Corporate governance, and its link with organizational controls, actions and conflicts, especially in the case of MNCs is a rich area for research. Emerging economies offer a unique opportunity to study the local–global dialectic and how change occurs.

2.2 Multinational Corporations and Practice Transfer

One of the consequences of the privatization process in emerging economies was the entrance of MNCs on local markets. The opportunities triggered by the globalization process and the fall of communism in emerging economies led to increasing attractiveness of these countries to MNCs. The impact of MNCs on local regulations and practices in emerging economies, on global and local economic development has recently become a hot topic in business research (Rugraff and Hansen 2011).

Transitional, East European countries such as Romania have been undergoing major post-communist restructuring projects, which meet the European restructuring industrial project, with cross-border foreign direct investment representing an important mechanism of the Single Market project. In this context, MNCs benefit from their international position, and gain “ability to arbitrage cross-national differences in tax, employment, credit, and other regulations as means by which to earn monopoly rents” (Rahman 2009, p. 86). This situation calls for a new reflection on corporate governance.

In many cases, governments in emerging economies are “too inexperienced and inept to regulate behavior” (Earle and Sapatoru 1994, p. 63), and therefore international models and requirements are an important vehicle for change. In this context, MNCs may bring to emerging economies new technology, knowledge, and skills (Rugraff and Hansen 2011), and therefore contribute to their economic development. However, in some cases, resistance to change and conflicts with informal rules may occur (Boytsun et al. 2011), or the legitimacy of the privatization process may hamper the positive economic effects (Denisova et al. 2012). Also, negative effects of MNCs entrance in emerging markets might also occur, especially when they bring low-level activities, use anti-competitive practices, provide poor quality products and services because of the quest for profits, divert profits, default on tax and wages payments, and do not reinvest the profits in the same country (Dyck 2001; Becht et al. 2005; Rugraff and Hansen 2011).

Communication between headquarter and subsidiaries and the manner in which coordination and cooperation occur within the group impact their competitiveness, the corporate governance model and their performance. Moreover, the corporate governance mechanisms of subsidiaries are influenced by the corporate governance systems of the home and host countries (Costello and Costello 2004) but also by informal rules (Boytsun et al. 2011). In exchange, the corporate governance of the subsidiary influences not only the cooperation with the headquarters, but also the wealth created and the share of this wealth going to the stakeholders (Costello and Costello 2004). Corporate governance mechanisms are influenced by the network of actors, because the role and actions of each governance actor (shareholders, board of director, government, or employees) are shaped by institutions, interests and generate conflicts and coalitions (Aguilera and Yip 2004). These actors play a very important role in the knowledge transfer and learning process. Moilanen (2007) discusses the accounting knowledge transfer from Western headquarters to a subsidiary in a former communist country and explores the interaction between past and present forces, the learning barriers and facilitators, and the balance between transferring practices and allowing for local adaptability and flexibility.

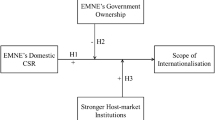

Some questions related to the role of MNCs in emerging economies are still under research: how do MNCs contribute to the development of the local environment, how does foreign ownership participation make corporate governance practices better (Rugraff and Hansen 2011), and how is it that the transfer of knowledge and practices is more successful in some cases than in others? Our study is presenting a case of success, as acknowledged by local actors, despite the pressure created around Petrom’s controversial privatization contract. In addition to that, this case allowed us to identify different corporate governance paradigms that coexist in the MNCs, as a consequence of the encounter with different contexts and actors.

3 Context and Research Methodology

In order to provide an in-depth analysis of improvements and transformations following a privatization in an emerging economy, and also to explore the actions and attitudes of various actors, our case study is set in Romania.

Romania is a relevant setting because of the various paces of change characterizing different periods after the fall of communism in 1989, and because of the variety in the outcomes of the privatization process. Cojocar (2013) provides examples of successful privatizations, which generated successful restructuring and economic performances, but also bankruptcies, delayed and unsuccessful restructuring, and negative economic and social effects. Under these circumstances, a case study approach is useful to understand how change was realized.

After the fall of communism, which set in motion a long process of transition marred by slow reforms and wrong political choices, especially beginning with the years 2000 a sound macroeconomic management and restructuring process started in Romania (Young 2010). An alignment to international standards was attempted, including in the field of corporate governance. A project to improve the corporate governance with the support of international organizations was launched and resulted in a Corporate Governance Code in 2001, revised and improved later, in 2008 (Olimid et al. 2009). However, implementing Western-based standards is not necessarily sufficient in order to improve practices, and there is evidence that “one size does not fit all firms in all countries” (Black et al. 2012, p. 935).

Despite recent progress, several studies suggest that disclosures and transparency still need improvement in Romania (Cuc and Kanya 2009; Young 2010; Răileanu et al. 2011). In analyzing the transparency index for 58 Romanian listed entities, Cuc and Kanya (2009) find out that Petrom has the highest level of transparency and identify significant differences between Romanian entities. Other studies also present Petrom as having sound corporate governance and financial reporting practices (Albu et al. 2011). However, Petrom had a controversial privatization which raised legitimacy issues (Lupu and Sandu 2010). These conflicting previous findings make Petrom an interesting case to study the implementation of corporate governance practices and their impact on the company’s performance and transparency.

Petrom is the biggest oil company in Central and Eastern Europe and the largest company listed on the BSE. Petrom’s privatization took place in 2004, when the Romanian Government sold the controlling interest to the Austrian group OMV. While privatization was, as noted, controversial, Petrom is currently considered a successful company, a model of good practices, and embracing such values as ethics, respect, partnership and a viable management vision. Starting in 2008, the company annually issues a Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) report. Following privatization, Petrom was restructured in terms of processes, IT systems, rules and people’s training. It became one of the most profitable Romanian companies and obtained massive profits even during the actual economic crisis. Its net profit grew in 2011 by 72 %, and while the 2012 increase was of only 5 %, the profit obtained (over 900 million EUR) is a record for Romania. Petrom’s Romanian CEO, Mariana Gheorghe, was deeply involved in the restructuring process and is perceived as having contributed to Petrom’s performance. She was the first Romanian to be included in Fortune 50 International Most Powerful Women in 2012 (an annual ranking of businesswomen worldwide). She is also Chairwoman of the BSE's Corporate Governance Board (responsible for issuing the Corporate Governance Code).

As a major limit of prior studies is the limited period of time for observations and their focus immediately before and after the privatization (Omran 2009), we employ a longitudinal case study covering a longer period of time (4 years). Thus we take a process view of the privatization, which allows us to understand its long-term implications. Archival data are collected from the annual reports and other information made available by the company, but also from press materials and prior research on Petrom. A content analysis of the annual reports of Petrom was performed in order to analyze the disclosures in corporate governance areas such as compliance with standards, social and environmental issues. Also, eight semi-structured interviews with IR officers from other major companies in Romania, as well as with relevant representatives of the financial community (financial analysts, brokers) were conducted.

We used the content analysis of four post-privatization annual reports of Petrom SA in order to identify the impact of privatization on the volume and quality of corporate disclosures. Also, we identified the type of corporate governance paradigm which characterizes these disclosures, by differentiating between the shareholders’ market based model, and the stakeholders’ relationship based model. The unit of analysis was the clause. These were grouped in 16 relevant topics. The clauses could be related to more than one topic and thus counted more than once. About 2,500 units of analysis were identified, following a cross-numbering protocol, and then allocated to the corresponding topic.

Content analysis relies on the postulate that repetition of units of analysis (words, expressions, sentences, paragraphs) reveals the interests and the concerns of the authors (Krippendorff 1980). The text is split and organized according to the choice of research objectives, and following an accurate coding method.

Our objective was to identify the main topics that emerged in Petrom’s corporate communication, after the privatization of the company. We used a manual treatment for the classification of disclosures in the annual report, and a semi-manual treatment for the numbering (the filters, the subtotals and the grand total are automatically generated). The cross-numbering increases the reliability of our searching and classification. The titles, tables, images, and graphics, or the localization of the information were not taken into account.

4 Results and Discussion

The 16 topics were partly derived from the literature review, partly derived from the particular context (according to the first part of this chapter) and partly inspired by the structure of the annual reports. Particular attention was given to defining the topics, so as to increase the reliability of the content analysis. The process implied developing additional classification rules, when specific questions were raised, with a constant care for coherence in classification. A final general consensus between the three coders was achieved, thus ensuring the reliability of the results (see Table 1 below).

Our analysis of corporate disclosures showed that even if pragmatic disclosures directly aimed at the shareholders were prominent, during the fours years of our analysis there is an important shift towards disclosure targeted at different categories of stakeholders, especially employees, customers, local communities, and society in general. MNCs have to face different audiences which, especially in the context of privatization, are not always favorable to the company, which often leads to increased legitimizing needs. The corporate governance market-based view, with a focus on shareholders, is not enough in these contexts. Stakeholders’ relationship models might prove more adapted, as we will see in the following discussion. The following sections present the four main themes under which were grouped the 16 research topics identified through the content analysis of the annual reports: compliance with standards, pragmatic issues, social issues, and strategy and self-assessment.

4.1 Compliance with Standards

The main strategy adopted by Petrom to gain legitimacy is showing that it abides by the laws, regulations, national and international or group standards. The main actions we identified are: compliance with group standards and compliance with national/international standards. Manipulation of the environment could also be identified, for example if we compare the declarations concerning environmental issues with the facts. For nine times in 2006 the maximum fine was imposed to Petrom for violation of the laws regarding the protection of the environment (Curentul 2006) and in May 2007 one of the two refineries of Petrom was temporarily shut down by the Romanian Authority of Environment Protection because of its lack of conformity with environmental standards (Ziarul Financiar 2007).

Compliance with predefined, accepted standards, whether these are OMV’s standards or national and international regulations, represents a major topic in the year following privatization, and it tends to plateau afterwards. Compliance with group standards can be directly related to privatization and its benefits, as pressures coming from different categories of stakeholders increased the need to legitimize the new status.

During 2005, it was agreed that Petrom would be fully aligned with OMV Group targets and strategy for 2010. (Annual Report 2005)

…implementing security standards at OMV level is of great importance. (Annual Report 2006)

2007 saw the establishment of an effective gas marketing business. The small gas distribution network was spun off into a wholly-owned company, Petrom Distributie Gaze srl, achieving compliance with the EU unbundling regulations. (Annual Report 2007)

Previous research has acknowledged that corporations are increasingly taking on, beside their role as economic actors, roles of political actors (Palazzo and Scherer 2006; Scherer et al. 2006). However, corporations’ acts of self-regulation (political activism, as Scherer et al. 2006 calls it) are regarded with mistrust by the public. As Scherer et al. (2006) puts it: “The self-imposed standards are often not the result of a broader and inclusive discourse with civil society. They are often implemented without any form of neutral third-party control. It is sometimes ‘business as usual’ that takes place behind the veil of well formulated ethical rules” (Rondinelli 2002).

4.2 Social Issues and Community Involvement

Care for the environment and prevention of environmental accidents are an important component of the corporate social responsibility, and as such, a powerful instrument of legitimacy towards the stakeholders:

…the company tried to meet its own environment objectives, by implementing several measures in line with the EU requirements. These measures related to the production technologies as well as product distribution. (Annual Report 2004)

The economic growth of the company implies also a great responsibility for the employees’ health and safety and for the environment. (Annual Report 2005)

Being a responsible industrial company, Petrom is committed to supporting efficient and well-managed utilization of energy sources and products, taking into account the needs of today’s consumers and the interest of future generations with respect to environmental protection. (Annual Report 2006)

The transformation and modernization of Petrom not only encompasses the company business, but also its role in the Romanian society. Consequently, management’s effort was also focused on transforming Petrom into a truly socially responsible company, involved in various areas of social development. (Annual Report 2007)

The declarations of the management concerning the measures taken to increase the health and the security of company’s employees represent a means to show that Petrom acts as a responsible employer concerned with the well-being of its human resources. These aspects are especially of interest for companies such as Petrom operating in hazardous industries, such as the energy industry.

A series of actions were taken in order to improve personnel working conditions in order to maintain production without incidents. These covered all elements of the work place system: operator//equipment//work task//work environment. (Annual Report 2004)

Petrom attaches utmost importance to providing high-quality medical care to its employees. Thus, we aim at promoting the health of our staff, maintaining their capabilities and improving their general well being. (Annual Report 2006)

The priority for 2007 was the implementation of the Petrom health concept, aimed at offering employees state-of-the-art medical services (occupational health, preventive and curative, and health management). (Annual Report 2007)

Petrom’s community involvement concerns the responsibility of the corporation towards the society at large. In Carroll’s (1979) theorization of CSR, this topic is to be found as the philanthropic responsibility of the company to contribute to various kinds of social, educational, recreational, or cultural purposes. Social responsibility is a major part of the legitimacy strategy of Petrom, as the amount of disclosure increases substantively over the four years post privatization, and is completed by a dedicated section in the company’s web site, and the creation of a department of CSR. This corresponds to the policy and structure of the OMV group.

We are a responsible company, perfectly aware of the importance required by health, safety and environment; Petrom is a company which has always been involved and will continue to be part of the community life, through actions developed for persons in need, said Mr Gheorghe Constantinescu, CEO of Petrom (Corporate News 2005).

We want to become not only a role model for the business community but also a responsible “citizen” of the community we are living in. (Annual Report 2006)

In order to enforce our social responsibility message, we created in 2007 a platform named “Respect for the future” under which we develop all our CSR programs. (Annual Report 2007)

The role of the company as defined by the company’s management is a role of education of the community, of a setter of high standards and of a responsible citizen.

As one of the largest companies in Romania we are aware of the impact of our activities on the Romanian society and we assume this important role by bringing our contribution to increasing the people’s confidence in the EU integration process, by applying high business standards, health and safety measures, both internally and externally, and by developing related projects. (Annual Report 2006)

The topic employees’ relations included assertions about the training and career of the employees. Petrom addresses employees directly, as a special stakeholder category, recognizing their contribution to the company’s prosperity:

One fundamental indicator of any company’s performance is the quality of its work force and the working conditions it provides its own employees. Petrom is a responsible employer committed to treating every employee with respect and dignity, providing a safe, hospitable and quality working environment, and to developing its management team through evaluation and definition of staff development measures, talent management programs, comprehensive training programs at European standards for all existing and future managers, as well as leadership and management programs. We recognize that a motivated, well-trained and diversified workforce represents a strong competitive advantage and a must have in the achievement of our target. (Annual Report 2006)

4.3 Pragmatic Issues: The Shareholders’ View

Besides disclosing information with a socially responsible color, Petrom also uses the disclosure of more pragmatic information such as: the development of the business, economic, financial and technical information, quality improvement, corporate governance, investments, and the evolution of prices.

In the topic development of the business we included the assertions regarding the expansion of the business, on the internal market as on the external market. This represents a way to obtain legitimacy based on the role of large corporations in the economic development of the region, and it can be related to the general welfare.

The privatization itself, through a significant capital increase and new forms of management, created the grounds of the most important growth of the company. (Annual Report 2004)

The sustainable and profitable growth of our company is of benefit to our shareholders, clients, employees and the Romanian economy in general and is therefore at the focus of all our activities. (Annual Report 2005)

An improved corporate communication with all the stakeholders and the creation of a corporate governance code is an important means of building legitimacy. The statements were mainly related to corporate governance issues and the target audiences being the shareholders and the analysts and in only a few cases the trade unions.

Starting with 2005 the Investor Relations function was established, enlarging the scope of work of the existing office dealing with the large individual investor base.(Annual Report 2006)

Petrom strongly believes that high corporate governance standards are essential tools to achieving business integrity and performance. This report sets out the policies and practices that Petrom applied during the year. (Annual Report 2007)

In 2007, the structure of the annual reports changed, a report of the Supervisory Board was introduced and the weight of the disclosure on corporate governance issues increased. Moreover, the company voluntary adopted in 2007 a corporate governance code, because no local code was available at that time.

Given that OMV Aktiengesellschaft has committed itself to fully observing the Austrian Code of corporate governance and because such a Code is not yet available in Romania, Petrom voluntarily adopted a corporate governance policy that outlines the governance principles and structures, focusing on the long term interests of shareholders and ensures the integrity of the governance process. (Annual Report 2007)

Assertions about prices comprised management’s declarations, justifying the increase in or the decrease of the price and the assessment of its effects on the company’s results. In the post-privatization context, the liberalization of prices appeared as a highly sensitive issue. Important pressure was placed by the political power on the management of the company to consider Romania’s economic and social situation in establishing the prices. The company tried to justify the increase in the prices on two bases – aligning prices to international quotations and increasing the profitability. Additionally, the management of the company proposed to contribute to the setting of a governmental fund to help those in need to cope with price increases.

In 2006, the international Platts quotations have registered big fluctuations. Acting according to its 2005 pricing policy, Petrom has adjusted its prices for terminal deliveries and retail pump sales to the price fluctuations at international level. The highest quotations in 2006 were registered in July, due to geo-political reasons (Iran and Middle East) and speculations on international commodity markets (there were fluctuations of USD 200 per ton in gasoline and USD 100 per ton in diesel). (Annual Report 2006)

Statements on quality improvement show an increased preoccupation with customer satisfaction, and are often related to innovation and modernization, as part of the new strategy. This sheds a favorable light on the privatization process.

As part of its newly defined strategy, the company aims to provide its customers with the best products and services available on the market. (Annual Report 2005)

The quality of the remaining chemical products was improved to international standards allowing access to more international customers. (Annual Report 2006)

The Exploration and Production Services division, following the acquisition of oil service business of Petromservice for EUR 328.5 mn, which will allow us to enhance the quality and efficiency of the operations and to support the reduction of production costs and the increase of production. (Annual Report 2007)

The quality improvement is a consequence of the modernization process. In 2006, we can notice an increased focus on assertions focusing on quality improvement and justifying prices increases.

A large part of the company’s assertions underline past accomplishments and future changes concerning the processes of restructuring, reorganization and modernization within the company. Restructuring, reorganization and modernization are key processes triggered by privatization and mark a fundamental change for the company:

2006 was a remarkable year for Petrom. The projects we implemented focused mostly on modernization, efficiency and profitability increase and on international expansion. … The Service Center Petrom Solutions and the introduction of the most important enterprise resource planning system, SAP, are just two of the projects that will lead to efficiency increase and cost reduction. The year 2006 was a landmark with regards to company reorganization, which is on track. (Annual Report 2006)

In 2007, the management will further continue to focus on efficiency improvement throughout the company by further implementing the modernization program that Petrom has embarked on during 2005. (Annual Report 2006)

2007 was a year of significant restructuring and modernization achievements and the laying of solid foundations for future growth and sustainable development. (Annual Report 2007)

It should be noted however, that the management only presents the favorable aspects of the process. For instance, since December 31st 2004 when Petrom had around 50,000 employees, the number of employees decreased to almost 33,000 employees due to the restructuring, and in consequence we would have expected more disclosure on this topic. This situation is at the core of the debate on new corporate governance models and the MNCs. As we could see, OMV is following the Austrian corporate governance code, based on a German stakeholder relationships model. Petrom, as part of OMV, has to follow both OMV’s corporate governance rules, and local regulations. However, at least from the disclosure point of view, it seems that employees are not as well represented as expected, and this can be the effect of a local dilution, based on a different cultural and societal setting. With an increasing number of cross-border mergers and acquisitions inside the European Union, we are facing now new challenges for the labor law and protection of employees,Footnote 2 with an impact on corporate governance rules.

An important means to build legitimacy, preponderantly used in the annual reports is to make use of numbers in order to show the evolution of the company’s financial and economic indicators. This type of strategy focuses on the usefulness of the activities for the immediate audiences, such as shareholders and customers. The information that did not match under any of the previous themes was included under the economic, financial & technical issues.

Petrom’s refineries will further increase efficiency and production to meet the rising market demand for petroleum products and the refineries will be in a position to fully process Petrom’s domestic oil production. (Annual Report 2004)

Investments appear as an important theme in the declarations of the management of the company, as a means to legitimate the new ownership of the company.

As part of the privatization contract, investments constantly appear in the annual report. In 2004, assertions regarding future investments are dominant, whereas in the following years achieved investments and plans of investments occupy a larger part in company’s disclosures:

The new fuels are the result of the revamping and modernization processes carried out in Petrobrazi and Arpechim supported by investments of approximately EUR 1 bn until 2010, declared Mr. Jeffrey Rinker, Member of the Managing Committee, in charge of Refining and Petrochemicals. (Corporate News 2006)

Investments are acknowledged regularly in the annual reports, being at the core of Petroms’s development strategy, and an important topic communicated to shareholders.

The growth of our business is fuelled by important investments aiming at improved efficiency and increased production. (Annual Report 2007)

4.4 Strategy and Self-Assessment

The presentation of the company’s strategy is an important theme in the annual reports, occupying more and more space as the years go by.

Our strategy aims towards turning Petrom into a more profitable company through modernization and implementation of information technology. (Annual Report 2004)

We committed ourselves to becoming the leading oil and gas company in South Eastern Europe, to investing in abating the effects of the natural decline and in stabilizing production in Romania. (Annual Report 2006)

In 2007, the information on corporate strategy occupied a more important weight as the company set its objectives for the year 2010.

We committed ourselves to becoming the leading oil and gas company in South-Eastern Europe leveraging on our role as the OMV Group operational hub for marketing in South-Eastern Europe and for exploration and production in Romania and the Caspian region. (Annual Report 2007)

This topic allows us to detect a “life cycle” of the company’s strategy which began in 2004 through defining some of the long-term objectives and which is re-launched in 2007.

After privatization, the company underwent a transfer of managerial knowledge from the Austrian mother company. In this transfer, as we could see, the corporate governance and investor relations held a structuring role, as they helped to improve constantly the corporate communication of the newly privatized company.

4.5 Assessments Made by Other Actors

As we could see in the previous analysis, the new management of Petrom assumed the role of educating the population in the spirit of market economy. This, in addition to extensive communication on the knowledge transfer and on the positive effects of the privatization for the different stakeholders, shows that the management took seriously the positive role of MNCs in the transition process.

Petrom’s performance as a good communicator was acknowledged through different awards obtained (for example – The Silver PR award for CSR communication in 2011, or the Golden PR award for non-commercial communication in 2007). In addition to that, representatives from the company were invited to different conferences on corporate reporting and investor relations, in order to talk about their practices, considered as best practices on the market (for example, the Amsterdam conference organized in 2008 by USAID).

In addition to these formal ways of recognition, we had the opportunity to interview several investor relations representatives from companies listed on the BSE, and other actors of the financial market (brokers, financial analysts), in order to confront their views with the image communicated by the management.

In general, multinationals that bought something (in Romania) didn’t find any interest in staying. And they didn’t have the elegance to be transparent. There are some exceptions. Petrom for instance is transparent. (local broker, working with MNCs)

We have always taken example from Petrom, which is a company listed on the Romanian market, but with Austrian influences. From this point of view it is very easy if you have a parent company that helps you with procedures, or at least with some lessons already learned, with experience in business, they can at least tell you what and how to learn. (Investor Relations representative of a company listed on the BSE)

Other local actors (from the market authority, and PR firms specialized in financial communication) confirmed the positive role that Petrom has played on the local market, from the point of view of good corporate communication practices and corporate governance. Compliance is related to the existing code, based on a shareholders’ model, and from this point of view the best practices promoted by Petrom on the local market are well acknowledged.

However, we could see in the content analysis that pressure coming from different stakeholders imposed enhanced communication towards non-shareholder audiences. Based on these findings, we will introduce in the next section a new debate, on the role of the MNC in arbitraging between different corporate governance models.

4.6 Corporate Governance Reports

We have chosen to study the 4 years following Petrom's privatization, focusing mainly on the annual reports. This analysis allowed us to observe increased disclosure aiming different stakeholders. Corporate governance issues represented an important chapter in corporate communication and a way for the company to promote a favorable image, especially for shareholders.

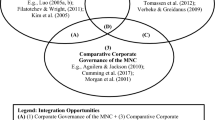

Moreover, the company issues a corporate governance report, under the Bucharest Stock Exchange regulations (the 2008 code). As mentioned in this report, Petrom wants to align with best international practices. On the company website, it is also stipulated that in addition to local regulations, the company is held to follow the internal standards of OMV (as we could also see in the previous analysis). From a corporate governance point of view, these are two different models, a local one of Anglo-Saxon inspiration, and the parent company one, of German inspiration. Therefore, if the BSE’s code acknowledges in a general manner the recognition of employees’ interests, the Austrian code is explicitly providing a direct role to employees’ representatives in the various governance instances of the corporation.

Rahman (2009) makes a thorough analysis of the differences between the German and the Anglo-Saxon model, and considers that “as the corporate landscape in the EU is transformed by the Single Market project, the prevalence of firms with multinational scope favors the adoption of explicit roles in corporate governance by non-shareholding stakeholders” (Rahman 2009, p. 92).

Based on our case study, we could observe that Petrom’s corporate communication gradually shifted towards non-shareholding stakeholders. This was on the one hand the effect of privatization, with pressure coming from various categories of stakeholders, and on the other hand it was the consequence of a new governance system coming from the mother company. From this point of view, we argue that emerging countries and transitional economies in particular represent a setting where the corporate governance models are challenged. However, we should note that disclosure is not in itself a guarantee for good corporate governance, as there is always a difference between corporate discourses and substantive action.

5 Conclusion

Our research is motivated by the complexity of the change processes in the field of corporate governance in emerging economies. Studies in this area are useful to assess the development of the corporate sector and the degree of adaptation to the business principles of the market economy (Abe and Iwasaki 2010). In this chapter we contributed to the debate on the role of MNCs in improving corporate governance in emerging markets. While it is considered that transfer of practices from the MNCs to the local firms is achievable, with positive impact on performance (Gołębiowska-Tataj and Klonowski 2009), the existing literature provides a variety of experiences in emerging economies (Omran 2009).

Exploring the case of Petrom, the largest Romanian listed entity on the BSE, we find that the role of MNCs as a vector of improvement for corporate governance in emerging economies can be explored at two different levels. First, at the local level, because MNCs set best practices, and become a benchmark for corporate reporting and corporate governance practices. Second, at the global level, as MNCs are confronted with new contexts, with complex stakeholder structures and various sources of pressure, they can represent a vector for future mutations in corporate governance models.

Therefore, these settings make possible the encounter between different models of corporate governance. This opens new debates on the convergence of corporate governance codes in the European Union, and on the role of MNCs as a vehicle for these models, and a source of hybridization. Future research should look into the transformation that is brought by the encounter between different social and cultural norms, and emerging countries represent an ideal setting for such research.

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

With freedom of movement, the MNCs might be tempted to choose the less restrictive settings, from an employee protection point of view (e.g. the case of Viking, and Laval in EU).

References

Abe, N., & Iwasaki, I. (2010). Organisational culture and corporate governance in Russia: A study of managerial turnover. Post-Communist Economies, 22(4), 449–470.

Aguilera, R. V., & Yip, G. S. (2004). Corporate governance and globalization: Toward an actor-centered institutional analysis. In A. Arin, P. Ghemawat, & J. E. Ricard (Eds.), Creating value through international strategy (pp. 55–77). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Albu, N., Albu, C. N., Bunea, S., Calu, D. A., & Gîrbină, M. M. (2011). A story about IAS/IFRS implementation in Romania – An institutional and structuration theory perspective. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 1(1), 76–100.

Annual Report. (2004). Petrom’s annual report. http://www.petrom.com/portal/01/petromcom/petromcom/Petrom/Raport_Anual. Accessed 12 June 2010.

Annual Report. (2005). Petrom’s annual report. http://www.petrom.com/portal/01/petromcom/petromcom/Petrom/Raport_Anual. Accessed 12 June 2010.

Annual Report. (2006). Petrom’s annual report. http://www.petrom.com/portal/01/petromcom/petromcom/Petrom/Raport_Anual. Accessed 12 June 2010.

Annual Report. (2007). Petrom’s annual report. http://www.petrom.com/portal/01/petromcom/petromcom/Petrom/Raport_Anual. Accessed 7 May 2011.

Becht, M., Bolton, P., & Röell, A. (2005). Corporate governance and control. ECGI Working paper series in, Finance, 2, www.ecgi.org/wp. Accessed 15 Sept 2013.

Black, B. S., de Carvalho, A. G., & Gorga, E. (2012). What matters and for which firms for corporate governance in emerging markets? Evidence from Brazil (and other BRIK countries). Journal of Corporate Finance, 18(4), 934–952.

Boytsun, A., Deloof, M., & Matthyssens, P. (2011). Social norms, social cohesion, and corporate governance. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 19(1), 41–60.

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance, academy of Management. The Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 497–505.

Claessens, S., Djankov, S., & Pohl, G. (1997). Ownership and corporate governance. Evidence from the Czech Republic. Policy Research Working Paper 1737. World Bank.

Cojocar, A. (2013) Industria trece printr-un val de închideri care afectează creşterea economică. Care sunt cauzele dezindustrializării de după’89 şi unde s-a greşit? Am privatizat prea mult sau prea puţin? De ce nu am atras destui noi investitori? (in Romanian) [The industry undergoes a wave of shut-downs which affect the economic growth. What are the causes of de-industrialization after’89 and what went wrong? Have we privatized too much or not enough? Why did we not attract more investors?], Ziarul Financiar, 7 Mar 2013.

Corporate News. (2005). Petrom corporate news, 26 May 2005. http://www.petrom.com/portal/01/petromcom/petromcom/Petrom/Relatia_cu_investitorii/Noutati_investitori/Noutati_investitori_2005. Accessed 11 Dec 2008.

Corporate News. (2006). Petrom launches a new line of fuels [10 Apr 2006], http://www.petrom.com/portal/01/petromcom/petromcom/Petrom/Biroul_de_presa/Arhiva_presa/Arhiva_2006. Accessed on 2 Feb 2008.

Costello, A. O., & Costello, T. G. (2004). Corporate governance in multinational corporations. Midwest Academy of Management annual conference, Minneapolis.

Cuc, S., & Kanya, H. (2009). Corporate governance – A transparency index for the Romanian listed companies. Annals of Faculty of Economics, 2(1), 60–66.

Curentul. (2006). Garda Naţională de Mediu "arde" Petromul [in Romanian]. http://www.curentul.ro/curentul.php?numar=20061020&cat=7&subcat=100&subart=45534. Accessed 15 June 2011.

Denisova, I., Eller, M., Frye, T., & Zhuravskaya, E. (2012). Everyone hates privatization, but why? Survey evidence from 28 post-communist countries. Journal of Comparative Economics, 40(1), 44–61.

Djankov, S., & Murrell, P. (2002). Enterprise restructuring in transition: A quantitative survey. Journal of Economic Literature, 40(3), 739–792.

Dyck, A. (2001). Privatization and corporate governance: Principles, evidence, and future challenges. The World Bank Research Observer, 16(1), 59–84.

Earle, J. S., & Sapatoru, D. (1994). Incentive contracts, corporate governance, and privatization funds in Romania. Atlantic Economic Journal, 22(2), 61–79.

Ezzamel, M., & Xiao, J. (2011). Accounting in transitional and emerging market economies. European Accounting Review, 20(4), 625–637.

Gołębiowska-Tataj, D., & Klonowski, D. (2009). When East meets West: corporate governance challenges in emerging markets of Central and Eastern Europe – The case of Polish Aggregate Processors. Post-Communist Economies, 21(3), 361–371.

Krippendorff, K. (1980). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. London: Sage.

Lupu (Ioan), I., & Sandu, R. (2010). Legitimacy strategies in the annual reports – What turn to social responsibility in post-privatization context. 33rd European Accounting Association (EAA) Annual Congress, Istanbul [working paper].

Megginson, W. L., & Netter, J. M. (2001). From state to market: A survey of empirical studies on privatization. Journal of Economic Literature, 39(2), 321–389.

Mennicken, A. (2008). Connecting worlds: The translation of international auditing standards into post-Soviet audit practice. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(4–5), 384–414.

Mickiewicz, T. M. (2009). Hierarchy of governance institutions and the pecking order of privatization: Central-Eastern Europe and Central Asia reconsidered. Post-Communist Economies, 21(4), 399–423.

Moilanen, S. (2007). Knowledge translation in management accounting and control: A case study of a multinational firm in transitional economies. European Accounting Review, 16(4), 757–789.

Olimid, L., Ionaşcu, M., Popescu, L., & Daniel, V. (2009). Corporate governance in Romania. A fragile start. The Proceedings of the 5th European Conference on Management Leadership and Governance, Athens, 5–6 Nov 2009.

Omran, M. (2009). Post-privatization corporate governance and firm performance: The role of private ownership concentration, identity and board composition. Journal of Comparative Economics, 37(4), 658–673.

Palazzo, G., & Scherer, A. G. (2006). Corporate legitimacy as deliberation: A communicative framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 66(1), 71–88.

Przybyłowski, M., Aluchna, M., & Zamojska, A. (2011). Role of independent supervisory board members in Central and Eastern European countries. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 8(1), 77–98.

Rahman, M. (2009). Corporate governance in the European Union: Firm nationality and the ‘German’ model. Multinational Business Review, 17(4), 77–98.

Răileanu, A. S., Dobroţeanu, C. L., & Dobroţeanu, L. (2011). Probleme de actualitate cu privire la măsurarea nivelului de guvernanţă corporativă în România (in Romanian) [Current issues in measuring the level of corporate governance in Romania]. Audit Financiar, 2011(1), 11–15.

Rondinelli, D. A. (2002, Winter). Transnational corporations: International citizens or new sovereigns? Business and Society Review, 107(4), 391–413.

Rugraff, E., & Hansen, M. W. (2011). Multinational corporations and local firms in emerging economies: An introduction. In E. Rugraff & M. W. Hansen (Eds.), Multinational corporations and local firms in emerging economies (pp. 13–47). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Scherer, A. G., Palazzo, G., & Baumann, D. (2006). Global rules and private actors: Toward a new role of the transnational corporation in global governance. Business Ethics Quarterly, 16(4), 505–532.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2008). Foreword. In G. Roland (Ed.), Privatization: Successes and failures. New York: Columbia University Press.

Young, P. T. (2010). Captured by business? Romanian market governance and the new economic elite. Business and Politics, 12(1), 1–38.

Ziarul Financiar. (2007). Petrom: The closing down of the refinery won’t have a major impact on the results, 30 May 2007.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Albu, N., Lupu, I., Sandu, R. (2014). Multinationals as Vectors of Corporate Governance Improvement in Emerging Economies in Eastern Europe: A Case Study. In: Boubaker, S., Nguyen, D. (eds) Corporate Governance in Emerging Markets. CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-44955-0_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-44955-0_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-642-44954-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-642-44955-0

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsBusiness and Management (R0)