Abstract

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory disease of unknown etiology with a variety of symptoms including abdominal pain, diarrhea, rectal bleeding, weight loss, and anemia. CD was firstly described as regional ileitis with chronic granulomatous inflammation of the terminal ileum in 1932. However, it is widely known to involve any part of the gastrointestinal tract from mouth to anus. The most common site of gastrointestinal involvement in CD is the ileocecal area, in which around 30 % of CD patients having disease located in this area. Isolated colonic disease occurs in another 30 % of patients and 10 % may have upper gastrointestinal involvement, while around one-third of patients may have perianal disease during their course of disease.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

2.1 Background

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory disease of unknown etiology with a variety of symptoms including abdominal pain, diarrhea, rectal bleeding, weight loss, and anemia. CD was firstly described as regional ileitis with chronic granulomatous inflammation of the terminal ileum in 1932 [3]. However, it is widely known to involve any part of the gastrointestinal tract from mouth to anus. The most common site of gastrointestinal involvement in CD is the ileocecal area, in which around 30 % of CD patients having disease located in this area [5]. Isolated colonic disease occurs in another 30 % of patients and 10 % may have upper gastrointestinal involvement, while around one-third of patients may have perianal disease during their course of disease.

Because there is no single gold standard test and pathognomonic symptoms or signs that can be used to definitively diagnose or determine the severity of CD, ileocolonoscopy is of pivotal importance in CD patients for the diagnosis, assessment of disease activity and extent, and cancer surveillance. It provides direct visual assessment and enables performing biopsy of the colonic and terminal ileal mucosa. Especially, biopsy of ileal mucosa can be achieved in at least 85 % of colonoscopies and increases the diagnostic yield of CD [7]. Moreover, ileocolonoscopy has been shown to be superior for the diagnosis of CD in the terminal ileum when compared with small bowel follow-through examination [12]. Therefore, achieving full colonoscopic evaluation including inspection of the terminal ileum has a critical value in assessing CD and has been accepted as the first-line procedure to establish the diagnosis of CD [24]. In the presence of severe and active, however, the value of full colonoscopy is limited by a higher risk of bowel perforation and flexible sigmoidoscopy or a radiologic imaging study may be safer in these circumstances. Ileocolonoscopy can be postponed until the clinical condition improves.

It is sometimes difficult to distinguish CD from other severe colitis because regenerative hyperplasia caused by heavy inflammation frequently conceals typical findings of CD. Therefore, accurate knowledge of endoscopic features with CD is mightily important for gastroenterologists to obtain optimal information about the disease.

2.2 Clinical Manifestations of Crohn’s Disease

The clinical manifestations of CD are more varied than those of ulcerative colitis. Signs and symptoms of CD can range from mild to severe and may develop gradually or abruptly. Similar with ulcerative colitis, symptoms including diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, fever, and rectal bleeding clinically reflect the underlying inflammatory process. Perianal fissures, fistulae, abscess, abdominal mass or tenderness, cachexia, and pallor can be observed as signs of CD patients (Table 2.1). Because of the transmural nature of the inflammation, fistulae, abscess, and perianal lesion favor the diagnosis of CD. Extraintestinal symptoms can include cutaneous manifestations, ocular inflammations, peripheral arthritis, spondylarthritis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis, and it will be described specifically in the following chapter.

Onset of CD is generally insidious, but it can also be presented with a fulminate onset or toxic megacolon. Recurrent abdominal pain usually occurs in ileal or ileocolic diseases, while diarrhea and rectal bleeding are observed significantly more often in colonic CD. Fistula complicates ileocolic disease more often than isolated colon involvement [10]. Predominant involvement of the mouth and gastroduodenal, jejunal, or perianal area can also be presented in CD patients but occurs in relatively fewer patients. Perianal manifestations are common and may precede the onset of bowel symptoms, particularly in the East Asian countries. CD limited to the appendix may mimic appendicitis [8].

It is sometimes difficult to distinguish CD from ulcerative colitis, jejunoileitis complicated by multifocal stenoses, bacterial overgrowth syndrome, intestinal tuberculosis, other chronic infectious enterocolitis, intestinal Behcet’s disease, or protein-losing enteropathy.

Because CD is a multifactorial polygenic disease with various aspect of phenotype, accurate classification of the disease might have potential advantages with respect to choosing medications, predicting prognosis, and deciding surgery. Especially, behavior of disease is strongly associated with indication for surgery; therefore, some investigators tried to clarify dominating features of CD. However, behavioral features such as penetrating type and fibrostenotic type often coexist, and classification by only disease behavior revealed to be unsuitable for reproducing it. In 1998, the World Congress of Gastroenterology in Vienna proposed a new classification of CD considering age of onset (A), disease location (L), and disease behavior (B) as the predominant phenotypic elements [6]. This classification seems easy to apply and relatively stable through time. However, some clinicians use Montreal revision of Vienna classification because of recent attentions such as early age of onset or perianal issues [19] (Table 2.2).

2.3 Endoscopic Findings for Initial Diagnosis

2.3.1 Gross Findings

Classical endoscopic findings of CD in colonoscopic examination include discontinuous chronic mucosal inflammation, aphthoid ulcerations, longitudinal ulcerations, and cobblestone appearance with normal surrounding mucosa. Skipped inflammatory lesions with normal intervening bowel segment are one of the key findings that differentiate CD from ulcerative colitis. Strictures, both fibrotic and inflammatory, may also be present. More than two-thirds of CD patients have colonic involvement which is divided into pan-colonic and segmental colitis. Approximately 40 % patients with colonic CD show rectal sparing from inflammation, while whole rectal involvement is usually observed in ulcerative colitis [13].

Relatively initial characteristic finding of CD is aphthoid ulcer (Fig. 2.1). It shows as a small (less than 5 mm sized), covered with exudates (whitish or yellowish), and superficial (flat or slightly raised) punched-out ulceration with reddish border. Other colitis which needs to be distinguished from CD such as intestinal Behcet’s disease, intestinal tuberculosis, and infectious colitis can also present this aphthoid ulcer. Thus, aphthoid ulcer itself is a nonspecific finding. Multiple presentations of aphthoid ulcers are more specific findings when diagnosing CD. Aphthoid ulcerations are developed over lymphoid follicles and frequently arranged along longitudinal axis of the colon in patients with early or mild CD (Fig. 2.2). Typical longitudinal ulcers of CD are thought to arise from these aphthoid ulcers in a longitudinal direction. Not only in the early stage can these aphthoid ulcers also be seen in the advanced stage of CD, especially around the main ulcerative lesions. Spotty erythematous lesions with localized edema (Fig. 2.3) of mucosa which are considered as beginning stages of CD also can be seen in the early state of CD.

As CD progresses, ulcers tend to be bigger and deeper. Adjacent mucosa shows grossly normal appearance. The shape of ulcers varies from round (Fig. 2.4) to irregular (Fig. 2.5). These types of ulcerations often present in a way of extensive irregular geographic borders or appearance of annular ulcers (Fig. 2.6) around intestinal lumen in CD. Therefore, in this case, it is difficult to differentiate from intestinal tuberculosis. However, the typical progress directions of the ulcerations are usually parallel to the axis of the colon (Fig. 2.7). Classic deep linear ulcerations with discrete margin are seen. Longitudinal alignment of ulceration might also be seen as a railroad track appearance (Fig. 2.8). In addition to linear mucosal features, serpentine mucosal lesion also can be observed by endoscopy in patients with CD, which may be accompanied by multiple geographic ulcers (Fig. 2.9).

As the ulcerations deteriorate, they coalesce into large network of lesions. Therefore, in active CD, the colonic mucosa may be thickened and swollen because of the intermittent pattern of diseased and healthy tissues. It is called as a “cobblestone” appearance, which is a highly specific finding of CD (Fig. 2.10). Remnant mucosal islands surrounded by ulcerations show edematous hyperplastic changes and look like multiple raised lesions. It is seen usually in the distal area of stenotic colon due to inflammation (Fig. 2.11); however, the small bowel near the terminal ileum is also able to show cobblestoning.

Long-standing CD with or without acute inflammation may be characterized by the presence of various mucosal changes including mucosal bridges, scars, fistulas, inflammatory polyps, and stenosis. As a result of fibrosis or scar arising from deep undermining ulceration (Fig. 2.12) and fissures, it can lead to mucosal bridge in the colonic mucosa (Fig. 2.13). During improvement of ulcerations, scars can be found by endoscopy (Fig. 2.14). Severe scarring change of the intestinal mucosa is sometimes indistinguishable from healed ulcerative colitis or infectious colitis such as salmonellosis. Inflammatory polyps also can be seen in patients with CD. These polyps are known as benign lesions caused by long-standing erosive inflammation of the intestine. Usually they are longer in dimension than are wide (Fig. 2.15).

As a result of repeated development and healing of ulcers, cicatricial contraction of bowel wall can be formed. Excessive contraction becomes severe stricture formation with ischemic damages (Fig. 2.16). Strictures can occur in the colon or small intestine and present single or multiple lesions. Sometimes, surrounding normal mucosa nearby stricture sticks together and makes diverticulum like structure, which is called pseudodiverticulum (Fig. 2.17). Most of the severe stricture can be managed by segmental resection and anastomosis; however, noninvasive intervention such as endoscopic balloon dilation can be applied in selected cases with short (<6 cm), moderately active lesions in generally good conditioned patients [9].

Recurrent severe transmural inflammation can lead to a resultant fistula (Fig. 2.18). Primary colonic fistulae are complications of CD, and sometimes the colon is secondarily involved due to small bowel Crohn’s disease [13]. Fistula formation can develop not only bowel to bowel but to the any part of the adjacent organs. Detailed materials will be discussed in “Complication” chapter.

2.3.2 Histological Findings

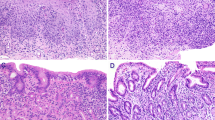

Endoscopic biopsy provides diagnostic clues to confirm the diagnosis of CD. Histological findings of CD (Fig. 2.19) can be summarized with transmural inflammation (span the entire depth of the intestinal wall), noncaseating granuloma (cheese-like appearance of granulomas associated with infections), chronicity, and focality. An increased cellularity of lymphocytes and plasma cells in the lamina propria implies chronic inflammations of disease. Crypt irregularity such as distortion, fibrosis extending to the muscularis mucosae, and noncaseating granuloma indicate another possibility of CD [11]. Noncaseating granulomas are observed in only 15–36 % in CD patients, whereas they are regarded as a prominent histopathologic feature of CD [21]. Histological results are just one of various diagnostic tools; therefore clinicians have to remember that biopsies are not meant to tell us everything about the disease.

2.3.3 Diagnostic Criteria for Crohn’s Disease [25]

Based on the findings above, the Japanese IBD study group has proposed the diagnostic criteria for Crohn’s disease [25] (Table 2.3). These criteria are relatively simple and easy to use in clinical practice. However, all other possible causes of longitudinal or cobblestone-appearing intestinal lesions such as ischemic colitis or ulcerative colitis must be excluded before confirming the diagnosis.

2.3.4 Small Bowel Evaluations

Inflammation is usually presented in the terminal ileum, but in some patients (10–30 %), small bowel proximal to the terminal ileum can be affected. Gastroduodenal and colonic evaluations are relatively easy, while small bowel is not readily accessible by conventional endoscopy. Until recently, the only way to evaluate the small bowel mucosa in a patient with CD was by barium small bowel radiographs and intubation of the distal terminal ileum. However, recent endoscopic modalities such as wireless capsule endoscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy enable direct visualization or biopsy of the deep small bowel mucosa. Typical small bowel lesions of CD (see Chap. 12) show aphthoid, round, or irregular ulcerations with a longitudinal arrangement at the mesenteric border [22]. Both wireless capsule endoscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy allow direct inspection of small bowel and may replace previous radiological methods [2].

2.3.5 Gastroduodenal Involvement of Crohn’s Disease

The most frequent finding of gastroduodenal involvement of CD is Helicobacter pylori-negative focally active gastritis with the 94 % positive predictive value [15]. Atypical mucosal abnormalities such as erosions and ulcers are able to be seen. However, characteristic appearance such as “bamboo joint-like appearances,” which are erosive fissures regularly traversing enlarged folds that longitudinally align the lesser curvature and cardia, can also be observed [26]. Details will be discussed in the following chapter.

2.4 Assessment for Disease Extent and Severity

Disease localization helps to determine the prognosis and appropriateness of medical treatment and assists in stratifying the risk of colon cancer. Furthermore, it can help in decision making in patients undergoing surgical therapy. A quantitative endoscopic index of severity (CDEIS) by dividing the bowel into five segments and generating numeric score based on surface involvement by disease and the presence of deep or superficial ulcerations was developed in the 1980s (Table 2.4) [14]. Because of the time-consuming and complicated nature of CDEIS, Daperno and colleagues developed another endoscopic grading system evaluating CD, the Simplified Endoscopic Activity Score for CD (SES-CD) (Table 2.5) [4

]. SES-CD was validated to be closely correlated with CDEIS. However, this index has not been used in routine clinical practice.

It is well known that endoscopic severity poorly correlates with clinical symptoms including CD activity index (CDAI, Table 2.6), while endoscopic extent and severity of the disease predict disease course. Therefore, endoscopic appearances in CD might be a better predictor of the future clinical course than CDAI. Moreover, after tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α blocking agents were launched, endoscopic confirmation of complete mucosal healing is believed to be associated with lower recurrence of the CD. Endoscopic scoring system has been developed and validated for assessing disease activity without interobserver deviation. However, regarding optimal treatment goal of CD (complete recovering of intestinal mucosa), it is still unanswered whether clinicians should rely on clinical, endoscopic, or histological mucosal healing during clinical practice.

2.5 Follow-Up Colonoscopy During Treatment of Crohn’s Disease

There are a lot of guidelines for endoscopic evaluation in managing patients with CD; however, the consensus is that a regular follow-up endoscopy is not generally recommended [20]. Universally recognized indications of endoscopy in patients with CD are gastrointestinal bleeding, severe abdominal pain suggesting intestinal stenosis, and preoperative evaluation (Table 2.7). In one pediatric study, 42 % rate of management change was found after endoscopic evaluation [23]. Follow-up colonoscopy in patients with CD might be deliberate given the invasive nature of endoscopy.

2.6 Surveillance for Colitic Cancer

Both CD and ulcerative colitis increase the incidence of colorectal carcinoma (CRC) and need surveillance colonoscopy. It is widely accepted that patients with CD, with a similar extent and duration of colonic involvement, have a similar risk to those with ulcerative colitis [1]. Established risk factors for developing CRC in the setting of colitis include the extent of disease, the duration of disease, and the severity of inflammation. Usually, more than one-third of colonic involvement in CD is a candidate for CRC surveillance. Surveillance programs have evolved with improvement on the understanding of the risk factors associated with CRC and the natural history of dysplasia. Pan-colonic chromoendoscopy with targeted biopsies of abnormal areas in every 1 or 2 years has emerged as the optimal surveillance technique in patients with colitis. In recent years, digital chromoendoscopy such as narrowband imaging has been introduced; however, its role in CRC surveillance in CD is underevaluated. Detailed explanations will follow in the next chapter.

2.7 Assessment for Postoperative Recurrence of Crohn’s Disease

Surgical intervention may be considered when treating complications of CD, for example, perforation or strictures that are not amendable to medical or endoscopic therapy. However, CD may recur after surgical therapy, especially at the site of anastomosis and its proximal border (Figs. 2.20, 2.21, and 2.22). It was reported in a meta-analysis that the pooled estimate of patients experiencing severe endoscopic recurrence was as high as 50 % [17]. It was also noted that there is a time lag between the development of endoscopic recurrence and clinical symptoms. Several guidelines have recommended that endoscopic reassessment should be considered at least 6 months after surgery to assess for recurrence, and further medical management may be adjusted according to the endoscopic assessment [24] (Fig. 2.23).

Evaluation and treatment of postoperative Crohn’s disease [16]

So far, Rutgeerts’ score (Table 2.8) is the gold standard scoring system for endoscopic evaluation of postsurgical recurrence in patients with CD [18]. If there is no lesion or mild recurrence less than five aphthoid ulcers on first year after surgery, clinical recurrence rate is 9 % at 7 year, while all patients with severe endoscopic recurrence showed symptomatic relapse within 4 years. However, although endoscopy plays an important role in evaluating postoperative recurrence in CD patients who have undergone prior bowel resections, routine postoperative endoscopic surveillance is still controversial, and it is still imperfect when recurrent lesions occur in the small bowel [2].

2.8 Summary

In summary, for any subjects with suspected CD, ileocolonoscopy and biopsies from the terminal ileum to colonic segments are necessary to establish the diagnosis. The introduction of anti-TNFα agents has changed the therapeutic paradigm of patients. Therefore, endoscopic examination has been increasingly used to monitor disease activity and mucosal healing in order to guide therapeutic decision making. Surveillance ileocolonoscopy has also changed recently from multiple random biopsies to pan-colonic dye spraying with targeted biopsies of abnormal areas. Ileocolonoscopy could be considered to assess preoperative risk stratification and postoperative recurrence so that therapy can be tailored accordingly. Most of all, clinicians should require careful judgment about performing endoscopy and making a clinical decision regarding endoscopic findings.

References

Cairns SR, Scholefield JH, Steele RJ, Dunlop MG, Thomas HJ, Evans GD, Eaden JA, Rutter MD, Atkin WP, Saunders BP, Lucassen A, Jenkins P, Fairclough PD, Woodhouse CR; British Society of Gastroenterology; Association of Coloproctology for Great Britain and Ireland. Guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in moderate and high risk groups (update from 2002). Gut. 2010;59(5):666–89. doi:10.1136/gut.2009.179804.

Cheon JH, Kim WH. Recent advances of endoscopy in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut Liver. 2007;1(2):118–25. doi:10.5009/gnl.2007.1.2.118.

Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Regional ileitis: a pathologic and clinical entity. 1932. Mt Sinai J Med. 2000;67(3):263–8.

Daperno M, D’Haens G, Van Assche G, Baert F, Bulois P, Maunoury V, Rutgeerts P. Development and validation of a new, simplified endoscopic activity score for Crohn’s disease: the SES-CD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60(4):505–12.

Freeman HJ. Application of the Montreal classification for Crohn’s disease to a single clinician database of 1015 patients. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21(6):363–6.

Gasche C, Scholmerich J, Brynskov J, D’Haens G, Hanauer SB, Irvine EJ, Sutherland LR. A simple classification of Crohn’s disease: report of the working party for the world congresses of gastroenterology, Vienna 1998. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2000;6(1):8–15.

Geboes K, Ectors N, D’Haens G, Rutgeerts P. Is ileoscopy with biopsy worthwhile in patients presenting with symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease? Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(2):201–6. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00201.x.

Hanauer SB, Sandborn W. Management of Crohn’s disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(3):635–43. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.3671_c.x.

Hassan C, Zullo A, De Francesco V, Ierardi E, Giustini M, Pitidis A, Morini S. Systematic review: endoscopic dilatation in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26(11–12):1457–64. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03532.x.

Lind E, Fausa O, Elgjo K, Gjone E. Crohn’s disease. Clinical manifestations. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1985;20(6):665–70.

Magro F, Langner C, Driessen A, Ensari A, Geboes K, Mantzaris GJ, Villanacci V, Becheanu G, Borralho Nunes P, Cathomas G, Fries W, Jouret-Mourin A, Mescoli C, de Petris G, Rubio CA, Shepherd NA, Vieth M, Eliakim R; European Society of Pathology (ESP); European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO). European consensus on the histopathology of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7(10):827–51. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2013.06.001.

Marshall JK, Cawdron R, Zealley I, Riddell RH, Somers S, Irvine EJ. Prospective comparison of small bowel meal with pneumocolon versus ileo-colonoscopy for the diagnosis of ileal Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(7):1321–9. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30499.x.

Mills S, Stamos MJ. Colonic Crohn’s disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2007;20(4):309–13. doi:10.1055/s-2007-991030.

Modigliani R, Mary JY, Simon JF, Cortot A, Soule JC, Gendre JP, Rene E. Clinical, biological, and endoscopic picture of attacks of Crohn’s disease. Evolution on prednisolone. Groupe d’Etude Therapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires Digestives. Gastroenterology. 1990;98(4):811–8.

Oberhuber G, Puspok A, Oesterreicher C, Novacek G, Zauner C, Burghuber M, Wrba F. Focally enhanced gastritis: a frequent type of gastritis in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1997;112(3):698–706.

Regueiro M. Management and prevention of postoperative Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(10):1583–90. doi:10.1002/ibd.20909.

Renna S, Camma C, Modesto I, Cabibbo G, Scimeca D, Civitavecchia G, Cottone M. Meta-analysis of the placebo rates of clinical relapse and severe endoscopic recurrence in postoperative Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(5):1500–9. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.066.

Rutgeerts P, Geboes K, Vantrappen G, Kerremans R, Coenegrachts JL, Coremans G. Natural history of recurrent Crohn’s disease at the ileocolonic anastomosis after curative surgery. Gut. 1984;25(6):665–72.

Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55(6):749–53. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.082909.

Schusselé Filliettaz S, Juillerat P, Burnand B, Arditi C, Windsor A, Beglinger C, Dubois RW, Peytremann-Bridevaux I, Pittet V, Gonvers JJ, Froehlich F, Vader JP; EPAGE II Study Group. Appropriateness of colonoscopy in Europe (EPAGE II). Chronic diarrhea and known inflammatory bowel disease. Endoscopy. 2009;41(3):218–26. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1119627.

Shen B. Endoscopic, imaging, and histologic evaluation of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:S41–5.

Sunada K, Yamamoto H, Hayashi Y, Sugano K. Clinical importance of the location of lesions with regard to mesenteric or antimesenteric side of the small intestine. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66(3 Suppl):S34–8. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2007.02.036.

Thakkar K, Lucia CJ, Ferry GD, McDuffie A, Watson K, Tsou M, Gilger MA. Repeat endoscopy affects patient management in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(3):722–7. doi:10.1038/ajg.2008.111.

Van Assche G, Dignass A, Reinisch W, van der Woude CJ, Sturm A, De Vos M, Lindsay J. The second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: special situations. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4(1):63–101. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2009.09.009.

Yao T, Matsui T, Hiwatashi N. Crohn’s disease in Japan: diagnostic criteria and epidemiology. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43(10 Suppl):S85–93.

Yokota K, Saito Y, Einami K, Ayabe T, Shibata Y, Tanabe H, Kohgo Y. A bamboo joint-like appearance of the gastric body and cardia: possible association with Crohn’s disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46(3):268–72.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kim, D.H., Chan, H.Ch., Lung, P.F.C., Ng, S.C., Cheon, J.H. (2015). Ileocolonoscopy in Crohn’s Disease. In: Kim, W., Cheon, J. (eds) Atlas of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-39423-2_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-39423-2_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-642-39422-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-642-39423-2

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)