Abstract

Sustainability-oriented innovation strategies are often based on assessments of what is ‘material’ for companies in the short run. Materiality assessments are increasingly used as the basis for sustainability strategies. Extant practice, however, often leads to reactive approaches that might be less innovative than required for the sustainability issue at stake and even lead to window dressing (‘talk but not walk’). Leading companies can fall prey to the ‘incumbent’s curse’—the failure to adequately adapt to changed circumstances. The adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provides an alternative frame for materiality assessments that has the potential to overcome the curse. Consequently, the corporate challenge becomes how to make the SDGs (more) material for the corporate innovation strategy. This paper makes the argument for ‘reversing materiality’ through the adoption of the SDGs—as a proactive way to escape the incumbent’s curse. Examples of emerging practices of leading companies are given.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction: Overcoming the Incumbent’s Curse

Leading (big) companies that apply sustainability-oriented innovation strategies could have a major—arguably decisive—impact on shaping a ‘better world’. There are basically two approaches that these companies can adopt: [I] innovation as an extension of existing business models that are based on present markets and needs or [II] innovation as an anticipation of new business models based on future markets and needs. The first approach relates to more gradual processes of—often incremental—innovation, whereas the latter approach has the potential of more radical—even disruptive—forms of innovation. The first approach is based on an extrapolation of trends; the second tries to ‘back-cast’ on the basis of desired future outcomes (Holmberg and Robert 2000). The first seems the least risky strategy of the two, but is also considered to lead to stagnation in those areas of sustainability where ‘transformational change’, or more system approaches, is required.

The literature in this respect talks about the ‘incumbent’s curse’: big companies that have a vested interest in the ‘old way’ of doing things, will consequently have great difficulties in changing and are therefore more inclined to bar change towards higher levels of sustainability—even if their leadership would be convinced that this is needed (Chandy and Tellis 2000). Incumbents fail to adapt in particular because of their inability to master new competencies and routines, due to their embeddedness within an established industry network that does not initially value the new technologies and societal ambitions. This poses a particular challenge to the leaders of these companies. Research on the incumbents’ curse has shown that this is an important factor why so many seemingly ‘big and powerful’ companies in the end might even disappear for lack of adaptation to new realities (ibid.). This phenomenon is also popularly known as the ‘Kodak-effect’, the experience of the leading photography company that created the world’s first digital camera but was not able (and/or willing) to change its business model accordingly. In 2012, the company went bankrupt.

However, incumbents sometimes succeed in facing radical transitions—even creating them—by investing in internal capabilities and relevant assets, by developing a proactive vision on where to go to and by redeploying and leveraging their innovative capabilities in the new technological and market domains that can be linked to particular sustainability issues (Hengelaar 2017). In short, by successfully adopting approach II they are able to ‘reinvent’ themselves through a particular business model innovation strategy. Philips or IBM are examples of companies that over time have ‘reinvented’ themselves several times. A company like Dutch Statement Mines (DSM) even changed sector three times over a number of decades—from mining, via fine chemicals to nutrition nowadays. These companies not only ‘adapted’ to changing (political-economic-technological) circumstances, but also were able to shape new (proto) institutions that enabled them to implement the change (De Geus 2002). An essential part of this strategy has always been to engage in partnerships and network relations with other organizations (Lawrence and Suddaby 2006) in order to engage in systemic change (Van Tulder and Keen 2018).

The integration of sustainability in the innovation strategies of companies is determined by the degree to which sustainability issues can be made ‘material’. A sustainable issue is material if ‘it could substantively affect the organization’s ability to create value in the short, medium or long term’ (IIRC 2013: 33). Corporations, however, are confronted with a large number of sustainability issues which create sizable dilemmas in determining what to address and what not (Van Tulder with Van der Zwart 2006). In the sustainability discourse, companies use so-called materiality assessments to determine the threshold at which specific sustainability issues are deemed so important by relevant stakeholders that they should address these in their strategy. Typically, materiality starts from the perspective of the company and prioritizes sustainability issues in direct response to stakeholder pressure.

In this chapter, we will explain (section “Materiality as a Principle”) the theory and principles behind the materiality process as well as the type of strategies existing materiality approaches tend to favour (section “Materiality in Practice”). It has been found that extant materiality techniques tend to prioritize incremental over radical forms of innovation. Companies often stimulate reactive practices of issue management and consider international sustainability challenges as tactical and risk-related challenges, rather than opportunities for growth and innovation. Overly conservative strategies in general tend to increase the occurrence of an incumbent’s curse.

However, we also notice a new take on the materiality challenge (section “Reversing Materiality: Applying the SDGs”), under the influence of the formulation of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In September 2015, all 193 UN governments agreed upon a joint ambition for the year 2030 that ranges from poverty alleviation to effectively addressing climate change and health problems (UN 2015). The achievement of most of these goals requires transformational change. Many incumbents have actually contributed to the formulation of these goals. International organizations (Global Compact, World Business Council for Sustainable Development [WBCSD]) argue that the 17 SDGs potentially have a very important impact on the purpose of enterprises all over the world. Studies (PwC 2015; Ernst & Young 2016) reveal that more than two-thirds of (big) companies around the world are already looking favourably at aligning with the SDGs. Furthermore, 87% of a representative sample of CEOs worldwide indicated that the SDGs provide an opportunity to rethink approaches to sustainable value creation (Accenture 2016). There is also a solid business logic to this ambition: it is estimated that achieving the Global Goals could open up an estimated US$12 trillion of economic opportunities in markets that require radical systemic change such as the food and health systems or whole cities (B&SDC 2017). Companies that embrace the SDGs share the potential to become ‘radical incumbents’ (B&SDC 2017), but of course only in the case they are able to integrate the SDGs in their strategies in a meaningful manner.

The biggest challenge, therefore, remains to move from rhetoric to practice. This means to embed SDGs in strategic activities and not only use them for philanthropic activities. Companies that try to succeed in making the SDGs part of their strategic planning, including their innovation strategy, have to make the SDGs material. In practice, this implies that the SDG agenda is successfully integrated in the materiality assessment of companies and that companies start ‘walking the talk’. This requires reversing the materiality logic from a corporate to a societal point of view. By selecting a universal agenda that will be relevant for at least 15 years, companies can channel not only their strategies, but also reap opportunities to rethink sustainable value creation and structure their sustainability efforts. Section “Reversing Materiality: Applying the SDGs” provides some examples of the way frontrunner companies are trying to integrate the SDGs in their innovation strategies. It is too early to assess the ultimate success of these approaches, but we can nevertheless conclude that reversing materiality is becoming a growing practice with promising prospects (section “Conclusion—A Promising Practice”).

Materiality as a Principle

Different stakeholders have diverse and non-aligned informational needs to make effective decisions. Materiality has become a reporting principle that is intended to provide stakeholders with ‘complete’ and ‘coherent’ information to assess a company’s performance (Calabrese et al. 2016; Edgley et al. 2015). Materiality is an interdisciplinary and multifaceted concept that operates as an information threshold in favour of the users of the information (Edgley 2014). It originated as an accounting and auditing concept in financial reporting. Its objective was to reduce risk to an acceptable level where its key determinant was whether the omission or misstatement would influence investor-decisions (Eccles et al. 2012). The materiality principle was introduced in the area of sustainability reporting by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) as part of its 2006 G3 reporting guidelines and updated in its 2011 3.1 and 2013 G4 guidelines. Materiality in this set-up is basically concerned with identifying those environmental, social and economic issues that matter most to a company and its stakeholders. It supposes that shareholders increasingly want to include the ethical perspective when taking decisions. Moreover, it acknowledges that shareholders are no longer the only stakeholders to focus on. Views of a wider group of stakeholders, such as customers, employees and communities, are taken into account. This implies a wider focus and different approach regarding what is important for business. In addition, it is intended to provide inputs for managing for the future—including a longer-term focus on issues that could affect a business strategy—and not about repeating what worked in the past (Murninghan and Grant 2013).

The fundamental function of materiality is filtering topics and prioritizing stakeholders. It therefore necessarily involves selection, inclusion and exclusion of information. This should result in reports that are centred on issues that are deemed the most critical to inform selected stakeholders of an organization (Jones et al. 2016; Eccles 2016). Consequently, it should help stakeholders to understand how sustainability issues can be a catalyst for innovation and growth and how these could be integrated in specific business activities (Bowers 2010). Defining materiality is therefore also seen and used as a legitimating tool to change stakeholders’ expectations (Manetti 2011).

The outcome of the materiality determination process is a materiality matrix. This matrix, in theory, enables a company to identify those (sustainability) issues that affect their long-term success. A materiality matrix shows all topics that are (perceived) of high, medium and low interest for the company as well as its stakeholders at this moment. It is supposed to be based on ‘what matters’ which is identified through a thorough internal analysis and stakeholder engagement. The archetypical materiality matrix confronts the importance of issues for stakeholders at the Y-axis (which identifies those topics that the company is supposed to ‘talk’ about) with the importance of these issues to the company on the X-axis (which identifies how important it is to ‘walk’) (Fig. 15.1). The materiality matrix then consists of at least four quadrants that present combinations of relative importance. The top right quadrant of a materiality matrix chart contains issues that are not only significant to the reporting company, but are also issues that the reporting company’s stakeholders care deeply about. GRI advices companies to spend the bulk of their report (talk) about how they are addressing these issues.

Materiality in Practice

Determining materiality means being engaged in a lengthy and repetitive process that often consists of the following steps: identification of material topics, prioritization, validation and review (GRI, G4). Seeking management support and stakeholder feedback are essential conditions. Different frameworks directed at different users of the disclosed information (e.g. Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) (investors), International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) (investors), GRI (all stakeholders)) can be used as guidance, but there is no generally accepted standard. Neither is there a universally accepted definition of materiality in the sustainability context.

In theory, the output of the materiality determination process is the disclosure of truthful and accurate information about a company’s performance and impact. In practice, this proves to be quite difficult since this information needs to be tailored to different stakeholder groups. Companies are then confronted with the question which stakeholders to select and what expectations to manage. Aligning corporate behaviour with stakeholder expectations has become a business priority (Dawkins 2005). Firms have to manage conflicting interests and objectives and articulate this in a credible way in order to drive learning and innovation (AccountAbility 2006). Sustainability reporting is considered an effective channel of communicating sustainability efforts, but a major risk is that companies only publish what management deems relevant or how they interpret and frame stakeholders’ concerns. A study of AccountAbility (2015) shows that most companies are using stakeholder engagement and materiality as risk-based tools to manage reputation, predominantly responding to stakeholders’ expectations and claims rather than opportunity-based tools to innovate.

Although stakeholders increasingly demand transparency in order to know the actual impact of organizations’ operations, transparency is an often-cited problem when talking about the materiality process. Frequently, companies don’t disclose how they determine the material issues (Mio 2010). In addition, the jury of the Dutch Transparency Benchmark, an annual research on the content and quality of sustainability reports of Dutch companies, indicated that ‘Only a few companies are transparent and honest regarding their own weaknesses vis-a-vis peers. The same applies for addressing and communicating on dilemmas: every company is faced with dilemmas, but not every company is transparent on these aspects’ (MoEA 2016: 17). The dilemmas that this quote refers to relate for instance to sequencing decisions: Which issue to take up first and how much money to spend on them. Another dilemma that in particular internationally operating companies face is how to deal with issues like human rights for which great cultural and regulatory differences exist between countries (Van Tulder 2018). IIRC (2013) concludes that sustainability communications are often a PR exercise, telling feel-good stories about a selection of less relevant issues and those that are easier to address, rather than a meaningful story about value creation.

The effective use of materiality matrices in sustainability reports is highly contested. The plotting exercise contains a large number of (often subjective) assessments and selections. Manetti (2011) indicates that stakeholders are often not involved in defining the contents of the report, and it’s not clear how representatives of the various groups are selected. There are also different incentives that drive the process. It may be mandatory because it is required by law (e.g. France, USA, South Africa), or voluntary as part of a sustainability reporting framework or simply to maximize the efficient use of resources. Critics indicate that materiality is not supposed to be an exercise in ticking the box. It should be about how the business activities affect the company’s viability and the lives of its stakeholders. This should result in an honest representation where positive and negative impacts are being taken into account for both current and future issues. This can then be a catalyst for planning and action.1

Studies on the use of materiality found that they tend to be more about intent than about performance: implementation is rarely guaranteed. Matrices are often supply driven instead of based on (tacit or future) needs. They are relatively static, whilst every year priorities shift due to changing stakeholder engagement, and they don’t sufficiently take into account diversity between and within stakeholder groups. Materiality matrices are regularly accumulated through consultation with a selected group of stakeholders that are willing to cooperate and participate in stakeholder meetings—but that are not necessarily the most critical or important ones. Corporate reports about the content of these stakeholder meetings hardly ever testify a discussion around serious dilemmas. Often there also exists a difference between the public matrix and the one that is being used for internal use. Furthermore, most matrices are very individualized assessments that do not show the industrial benchmarks used by peers and investors to compare performance nor key sustainability performance indicators within an industry (Bouten and Hoozée 2015; Murninghan and Grant 2013; Zhou and Lamberton 2011).

In addition, KPMG (2014) found that senior management is not always involved in the materiality assessment process. If the sustainability team is only in charge, and there is no company-wide support for the process and outcomes, the board is less likely to take sustainability issues into account when making vital decisions regarding corporate value creation and resilience. This makes the discourse less material. Ceres even claims that ‘where sustainability is material to a company, boards have a fiduciary responsibility to act’ (2017: 4). This implies that companies should focus on integrating sustainability into strategy and also on achieving long-term results. Other challenges as identified by KPMG are: material topics are too broad or overlap, which makes it difficult to evaluate whether companies are managing them adequately, and there are more material issues than the company can (or wants to) manage which makes it harder to understand the company’s impacts and priorities.

Reversing Materiality: Applying the SDGs

By introducing the SDGs to the discourse on sustainable development, including major universal topics as defined by society in general and not only by their own (selected) stakeholders, companies are potentially taking a first step to get out of a reactive approach and to move towards a more active approach. This trend is strongly endorsed by international organizations (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], World Resources Institute [WRI], WBCSD, World Economic Forum [WEF]) which emphasize that feeding the SDGs into a firm’s strategic planning process is a major opportunity for a company’s long-term success.

The SDGs can inform a company’s materiality analysis, serve as a lens in goal-setting and help define the relevant issues for the sector, value chain or country the company is operating in. The common framework of action and language that the SDGs constitute provides a unified sense of (long-term) priorities and purpose which facilitates communication with stakeholders. The goals reflect stakeholder expectations and future policy direction at the (inter)national and regional level. Hence, advancing the SDGs can help mitigate legal, reputational and other business risks. But more importantly, it can further a better understanding of the sustainability context and enable companies to shape and steer their business activities and capture future opportunities through products and services that address global societal challenges (GRI et al. 2015; WBCSD 2015). In this way, they can engage more deeply as a positive and strong influence on society (Bakker in PwC 2015).

The engagement of big companies with the SDGs, however, still takes place in a climate of considerable distrust and scepticism as to the real motivations of companies. Are they willing to walk the talk? The 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer2 shows that 75% of general public around the world agree that ‘a company can take specific actions that both increase profit and improve the economic and social conditions in the community where it operates’. Nevertheless, research of Corporate Citizenship3 (2017) shows that businesses have the tendency to use the SDGs for communications, but they neglect the strategic implications. Moreover, whilst 99% of the respondents said that their company was aware of the SDGs, 20% indicated that their employers had ‘no plans to do anything about them’.

Sceptics—as well as the optimists—participate in a complicated discourse on the question whether (big) companies are actually willing and able to contribute to sustainable development. Companies have four strategic options (cf. Fig. 15.1):

-

1.

Don’t talk and don’t walk (Inactive): This is the traditional (neoclassical) view on companies in which they adopt a narrow ‘fiduciary duty’—with only direct and short-term responsibility to shareholders and owners without taking into account negative externalities like pollution—and consequently keep to relatively simple goals like profit maximization. This position feeds into low expectations/trust of society on the ability of companies to contribute to sustainability.

-

2.

Talk, but don’t walk (Reactive): This is the archetypical reason why sceptics refer to ‘green-washing’—or in the case of UN initiatives ‘blue-washing’ (blue is the colour of the UN)—of companies. It happens when companies are not serious about their contribution to sustainability, but nevertheless suggest the opposite. This can also apply to companies that are more serious about sustainability issues, but nevertheless limit their sustainability strategy to marginal activities (and organize this for instance in their philanthropic foundation). Some are already talking about ‘SDG washing’.4

-

3.

Walk, but don’t talk (Active): Faced with the societal trust gap, a number of frontrunner organizations are choosing not to talk (too much) on their societal ambition, for fear of not being able to satisfy all critics. For instance, when operating in countries with corrupt regimes, it is not always wise to be too transparent on a number of issues.

-

4.

Talk and Walk (Proactive): This creates alignment of trust in case of well-communicated processes, but because most issues are very complex and take considerable time, there is no guarantee that companies that are willing to really integrate sustainability in their corporate strategy are actually able to do this. The managerial challenge becomes not only which issue to prioritize, but also what to communicate and which stakeholder to engage. Talking becomes a precondition for implementing strategic intent.

Companies that adopt options 1 and 2 reinforce the idea of an ‘incumbents’ curse. Options 3 and 4 could be evidence of radical incumbents that aim at disruptive sustainability. The Business & Sustainable Development Commission (2017) sees evidence that radical incumbents arise. They observe that already thirty Global Goal ‘unicorns’5—as they call them—exist with market valuations of more than US$ 1 billion. They have made the SDGs material by integrating them into corporate strategy (option 3) as well as engaging others in their strategy to create an enabling environment (option 4). The more companies are able to line up with partners across their own sector as well as with non-commercial parties, the more they are able to create an enabling environment that can create radical or disruptive innovation (Van Tulder et al. 2014). In the latter case, coalitions of parties create new institutions (new rules of the game) that can speed up the spread of disruptive sustainability tremendously in particular when supported by (big) incumbents.

The SDGs, when used to broaden the materiality approach as an input for strategic planning and innovation, require that companies move beyond their own previous selection of material issues and don’t ‘repackage’ old priorities to fit the SDG agenda. The challenge is not to pick the easiest, most positive or obvious goals, but to select those that can become truly material to the future business of the company (PwC 2015). Nevertheless, this is no easy task since the SDG ambition level is high and the required innovations are generally considered too systemic (which often implies radical change). This predicament can result in a short-term focus with relatively quick wins to boost the company’s performance instead of transforming core business strategies. Corporations can have a ‘selection bias’: only those issues receive priority that they would have embraced for defensive reasons. Applying the original definition of materiality becomes additionally challenging with the inclusion of more than a limited number of SDG: How to find agreement on what actually entails corporate ‘performance’ (with or without societal impact) or ‘complete’ and ‘coherent’ information? The Business & Sustainable Development Commission (2017) argues that by prioritizing the right Global Goals in their strategy agenda, companies cannot only anticipate the disruption that is likely to appear in the future, but also shape the direction of the disruption to their competitive advantage due to concomitant alliances with other societal stakeholders that have helped in formulating these specific goals. Shared goals—even if companies were not part of their formulation—are a precondition for strategic alignment between potential partners (PrC 2015).

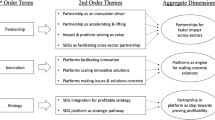

Making the SDGs ‘material’ not only necessitates internal change of companies, but also requires input from external alliance partners to facilitate change in the right direction. Companies can apply different strategies for this: through their CSR department, linked to strategy, in combination with their suppliers or buyers even more directly linked to their innovation strategies. Since the finalization of the SDGs, many companies have been using the SDG framework in a variety of ways, from reactive to proactive. Not many companies have really tried to make an explicit link with a possible business model innovation. But there are exceptions emerging. Take for instance the approach adopted by three Dutch frontrunner incumbents: Philips, DSM and Unilever (Table 15.1).

From interviews with all three companies, we have learned that they all initially considered all SDGs in internal discussions involving strategic departments and on occasion also suppliers. Two of the three companies linked their interest for the SDGs directly to their innovation strategy. Two also made the link between the SDGS and their supply chain and community involvement strategies. The latter strategy is often more susceptible to PR consideration. All set concrete (material) global sustainability ambitions: Philips6 aims at creating access to health for 3 billion people by 2025; Unilever7 aims at helping more than 1 billion people ‘take action to improve their health and well-being’ by 2020. DSM8 was less specific, but identified three key areas in which the company can drive sustainable markets: nutrition, climate changeand circular economy. All three companies acknowledge that their international scale and innovative capacity—the characteristics of an incumbent firm—are essential qualities to provide solutions to urgent societal challenges. A strategic support of the SDGs—i.e. explicitly linked to core activities and future markets—helps corporate leadership to align internal and external stakeholders. Whether they will succeed in this ambition and how fast, is still unknown. But all three companies have reinvented themselves several times over their more than 100-year history, which in any case makes them relevant benchmarks for measuring the success of a reversed materiality approach based on the SDGs. Not in the least because they themselves have identified the SDGs as key driver for their strategic decisions.

Conclusion—A Promising Practice

In this chapter, we argue that reversing materiality considerations, as well as the related techniques for involving stakeholders, is a necessary condition for using the SDGs as strong mechanism for guiding strategic planning. Companies not only have to address their own issue priorities—largely as part of a risk management strategy—but they also have to look at future possibilities as part of an opportunity-seeking strategy. Reversed materiality can consequently be based on landscaping, stakeholder engagement or scenario techniques—that have partly also been used in ‘backcasting’ practices. Departing from societal needs and ambitions, as defined in multi-stakeholder engagement processes, seems to create in particular promising venues for a process of internal and external alignment. It potentially breaks through an overly conservative type of materiality approach that is now practised by many companies and which might make them susceptible for the effects of an incumbent’s curse. By proactively allying with societal stakeholders, leading companies actually can create their own ‘enabling environment’ for successfully implementing radical innovation strategies.

This chapter discussed the origins of extant materiality practices of companies, which can be traced back to accounting and risk management. The approach has also been introduced in the area of sustainability as a leading principle in the management of stakeholders and issues. The concept of materiality helps big (incumbent) companies in theory to provide a credible and accurate view of its ability to create and sustain value. It can inform company strategy and decision-making as it shows the areas where it has most substantial impact. We argued that in practice issue prioritization is often a reactive approach where companies choose to report on the relatively ‘easy to solve’ topics or only on those subjects that have been negatively pointed out by stakeholders. This attitude seriously lowers the ability of the company to really (materially) integrate the SDGs in their strategic planning.

The SDGs, by their set-up and framing, provide a unique opportunity for companies to engage more proactively with stakeholders. The major challenge is how to make the SDGs more ‘material’ than existing stakeholder approaches. We discussed some general expectations and considered some specific examples of the way frontrunner companies are using the SDGs to move away from incremental to innovation strategies that link to a more radical (systemic) change agenda. Note however, that in non-conducive circumstances a proactive strategy is more difficult to achieve and requires not only internal change but also an extended portfolio of cross-sector partnerships. Internal alignment and external alignment have to be combined and should be aimed at creating so-called proto-institutions (Lawrence and Suddaby 2006) which can create a first-mover advantage for the companies that are able to reorganize their environment (Van Tulder and Keen 2018). Reversing the materiality approach implies that companies move from an inside-out orientation in issue prioritization and strategy building to a more outside-in approach in which societal needs are considered material. Issues can only be selected as low or high priority for the short term or longer term after close consideration of the interrelation of these needs with the company’s present and future possibilities to create societal value.

Notes

-

1.

http://csr-reporting.blogspot.nl/2014/12/why-materiality-matrix-is-useless.html.

- 2.

-

3.

https://corporate-citizenship.com/wp-content/uploads/Accelerating-Progress-on-SDGs-2017.pdf.

- 4.

-

5.

To mention a few: well-known companies like Nissan (in joint venture with Enel Group) or Merck, but also smaller and less well-known companies are classified as ‘unicorns’ like Didi Chuxing, GuaHao or MicroEnsure.

-

6.

https://www.philips.com/a-w/about/investor/philips-investment-proposition.html.

-

7.

https://www.unilever.com/sustainable-living/improving-health-and-well-being/.

-

8.

https://www.dsm.com/corporate/sustainability/vision-and-strategy.html.

References

Accenture, UN Global Compact. 2016. “Agenda 2030: A window of opportunity.” The UN Global Compact-Accenture Strategy CEO survey. Accessed July 23, 2018. https://www.accenture.com/t20161216T041642Z__w__/us-en/_acnmedia/Accenture/next-gen-2/insight-ungc-ceo-study-page/Accenture-UN-Global-Compact-Accenture-Strategy-CEO-Study-2016.pdf#zoom=50.

AccountAbility. 2006. “The materiality report: Aligning strategy performance and reporting.” Accessed July 23, 2018. http://www.accountability.org/publication/materiality-report-aligning-strategy-performance-reporting/.

AccountAbility. 2015. “Beyond risk management—Leveraging stakeholder engagement and materiality to uncover value and opportunity.” Accessed July 23, 2018. http://www.accountability.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Beyond-Risk-Management-Stakeholder_Engagement_and_Materiality.pdf.

Bouten, Lies, and Sophie Hoozée. 2015. “Challenges in sustainability and integrated reporting.” Issues in Accounting Education 30 (4): 373–81.

Bowers, Tom. 2010. “From image to economic value: A genre analysis of sustainability reporting.” Corporate Communications 15 (3): 249–62.

Business & Sustainable Development Commission (B&SDC). 2017. “Better business, better world.” Accessed July 23, 2018. http://report.businesscommission.org/.

Calabrese, Armando, Roberta Costa, Nathan Levialdi, and Tamara Menichini. 2016. “A fuzzy analytic hierarchy process method to support materiality assessment in sustainability reporting.” Journal of Cleaner Production 121: 248–64.

Ceres. 2017. “Lead from the top: Building sustainability competence on corporate boards.” Accessed July 23, 2018. https://www.ceres.org/resources/reports/lead-from-the-top.

Chandy, Rajesh K., and Gerard J. Tellis. 2000. “The incumbent’s curse? Incumbency, size, and radical product innovation.” Journal of marketing 64 (3): 1–17.

Dawkins, Jenny. 2005. “Corporate responsibility: The communication challenge.” Journal of Communication Management 9 (2): 108–19.

De Geus, Arie. 2002. The living company: growth, learning and longevity in business. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Eccles, Robert G. 2016. “Sustainability as a social movement.” CPA Journal 86 (6): 26–31.

Eccles, Robert G, Michael P. Krzus, Jean Rogers, and George Serafeim. 2012. “The need for sector-specific materiality and sustainability reporting standards.” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 24 (2): 65–71.

Edgley, Carla. 2014. “A genealogy of accounting materiality.” Critical Perspectives on Accounting 25 (3): 255–71.

Edgley, Carla, Michael J Jones, and Jill Atkins. 2015. “The adoption of the materiality concept in social and environmental reporting assurance: A field study approach.” The British Accounting Review 47 (1): 1–18.

Ernst & Young. 2016. “Sustainable Development Goals What you need to know about the Sustainable Development Goals and how EY can help.” Accessed July 23, 2018. https://www.ey.com/au/en/services/specialty-services/climate-change-and-sustainability-services/ey-lets-talk-sustainability-issue-7-the-sustainable-development-goals-what-role-can-companies-play.

GRI, UN Global Compact and WBCSD. 2015. “SDG compass—The guide for business action on the SDGs.” Accessed July 23, 2018. https://sdgcompass.org/.

Hengelaar, Gerbert. 2017. “The pro-active incumbent: Holy grail or hidden gem?” PhD diss., ERIM: RSM Erasmus University.

Holmberg, John, and Karl-Henrik Robert. 2000. “Backcasting—A framework for strategic planning.” International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 7 (4): 291–308.

International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC). 2013. “Materiality Background Paper for <IR> .” Accessed July 23, 2018. http://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/IR-Background-Paper-Materiality.pdf.

Jones Peter, Daphne Comfort, and David Hillier. 2016. “Sustainability in the hospitality industry: Some personal reflections on corporate challenges and research agendas.” International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 28 (1): 36–67.

KPMG. 2014. “Sustainable insight: The essentials of materiality assessment. KPMG International. Sustainable insight: The essentials of materiality assessment.” Accessed July 23, 2018. https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/cn/pdf/en/2017/the-essentials-of-materiality-assessment.pdf.

Lawrence, T., and R. Suddaby. 2006. “Institutions and institutional work.” In Handbook of organization studies, edited by S. R. Clegg, C. Hardy, T. B. Lawrence, and W. R. Nord. 2nd ed., 215–54. London: Sage.

Manetti, Giacomo. 2011. “The quality of stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting: Empirical evidence and critical points.” Corporate Social—Responsibility and Environmental Management 18 (2): 110–22.

Mio, Chiara. 2010. “Corporate social reporting in Italian multi-utility companies: An empirical analysis.” Corporate Social—Responsibility and Environmental Management 17 (5): 247–71.

MoEA (Ministry of Economic Affairs). 2016. “Transparency benchmark 2016 the crystal.” Accessed July 23, 2018. https://www.transparantiebenchmark.nl/sites/transparantiebenchmark.nl/files/afbeeldingen/transparantiebenchmark_eng.pdf.

Murninghan, Marcy, and Ted Grant. 2013. “Corporate responsibility and the new ‘materiality’.” Corporate Board 34 (203): 12–17.

PrC (Partnerships Resource Centre). 2015. “The state of the partnership report-2015.” Rotterdam: RSM. Accessed July 23, 2018. https://www.rsm.nl/fileadmin/Images_NEW/Faculty_Research/Partnership_Resource_Centre/CSO_Can_partnerships_provide_new_venues.pdf.

PwC (PricewaterhouseCoopers). 2015. “Make it your business: Engaging with the Sustainable Development Goals. Accessed July 23, 2018. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/services/sustainability/sustainable-development-goals/sdg-research-results.html.

United Nations, General Assembly. 2015. “Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for Sustainable Development.” A/RES/70/1.

Van Tulder, Rob, with Alex Van Der Zwart. 2006. International business-society management: Linking corporate responsibility and globalization. London: Routledge.

Van Tulder, Rob, Rob Van Tilburg, Mara Franken, and Andrea Da Rosa. 2014. Managing the transition to a sustainable enterprise. London: Earthscan/Routledge.

Van Tulder, Rob, and Nienke Keen. 2018. “Capturing collaborative challenges: Designing complexity-sensitive theories of change for cross-sector partnerships.” Journal of Business Ethics 150 (2): 1–18.

Van Tulder, Rob. 2018. Getting all the motives right. Driving international corporate responsibility to the next level. Rotterdam: SMO books. https://smo.nl/publicatie/getting-all-the-motives-right-driving-international-corporate-responsibility-icr-to-the-nextlevel/.

WBCSD (World Business Council for Sustainable Development). 2015. “Reporting matters—Redefining performance and disclosure.” Accessed July 23, 2018. http://wbcsdpublications.org/project/reporting-matters-2015/.

Zhou, Yining, and Geoff Lamberton. 2011. “Stakeholder diversity versus stakeholder general views: A theoretical gap in sustainability materiality conception.” In Proceedings 1st World Sustainability Forum 1–30 November 2011, Basel Switzerland, edited by Julio A. Seijas and Maria del Pilar V. Tato. Basel: MDPI.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

van Tulder, R., Lucht, L. (2019). REVERSING MATERIALITY: From a Reactive Matrix to a Proactive SDG Agenda. In: Bocken, N., Ritala, P., Albareda, L., Verburg, R. (eds) Innovation for Sustainability. Palgrave Studies in Sustainable Business In Association with Future Earth. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97385-2_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97385-2_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-97384-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-97385-2

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)