Abstract

Trauma Systems Therapy for Refugees (TST-R) is an innovative, trauma-informed multi-tiered approach to mental health prevention and intervention with refugee children and their families. TST-R was developed as an adaptation of Trauma Systems Therapy (TST), which is an organizational and clinical model that focuses on both a child’s dysregulation and the social environmental context that may be contributing to ongoing symptoms in the aftermath of trauma. TST-R adaptations address multiple barriers to care for refugees and their families through innovative mental health service delivery including multi-tiered approaches to community engagement and stigma reduction, embedding of services in the school setting, partnership building, and the integration of cultural brokering throughout all tiers of intervention to provide cultural knowledge, engagement, and attention to the primacy of resettlement stressors. TST-R has been shown to be effective in engaging refugee youth in services and reducing symptoms of PTSD and depression.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Background

In recent years the world has witnessed a growing refugee epidemic, with approximately 65 million people forcibly displaced from their homes by the end of 2015 (United States High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 2016). In 2016, the United States resettled 84,995 refugees while other nations received millions of refugees and displaced persons fleeing across their borders or seeking refuge upon their soil (Bureau of Population, Refugees, & Migration, 2017; UNHCR, 2016). Refugees and displaced persons are seeking refuge from multiple conflicts worldwide and related exposure to violence, terrorism, torture, and loss of resources. Of those displaced, approximately 21.3 million are considered refugees and over half of these refugees are under the age of 18 years old (UNHCR, 2016). The number of new asylum applications submitted by unaccompanied or separated children worldwide also increased significantly from 34,300 in 2014 to 98,400 in 2015 (UNHCR, 2016). The mounting impact of conflict and displacement on young people and their caregivers calls for increased innovation and responsiveness to meet this population’s health and mental health needs.

Trauma Exposure and Mental Health Needs Among Refugees

Throughout their journeys, refugee children and their families are often exposed to traumatic events such as direct and indirect acts of violence, physical and sexual abuse, torture, physical injury, loss and family separation, exposure to extreme living conditions, malnutrition, and lack of access to basic resources (Fazel & Stein, 2002; Reed, Fazel, Jones, Panter-Brick, & Stein, 2012). Refugees also demonstrate exceptional resilience, as evidenced by their survival of extreme circumstances and efforts to seek relative safety in a new country (Betancourt & Khan, 2008). Refugee children are at risk, however, for short and long-term health and mental health difficulties including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, attention, and behavioral problems (Bogic, Njoku, & Priebe, 2015; Fazel & Stein, 2002; Reed et al., 2012). Further, while heightened exposure to violence and trauma can increase the risk of these symptoms, studies suggest that other factors in their social environment may exacerbate or ameliorate these symptoms over time (Reed et al., 2012; Sundquist, Bayard-Burfield, Johansson, & Johansson, 2000). The refugee experience is defined by disruptions in the social-ecological environment of children during the course of their development and throughout their pre-migration, flight, and resettlement journey. Research suggests that the long-term impact of trauma exposure can be related to multiple factors including parental adjustment, child temperament, and other social environmental factors such as financial strain, lack of social support, discrimination, family conflict, and reminders of trauma (Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine, 2000; Catani, Jacob, Schauer, Kohila, & Neuner, 2008; Khawaja, White, Schweitzer, & Greenslade, 2008; Sundquist et al., 2000). Upon resettlement, social environmental stressors associated with resettlement, acculturation, and social isolation may also be important factors to consider in the adjustment of youth. Therefore, even once families are resettled in new communities, they remain at risk not only of exposure to new trauma such as community or domestic violence, but also to the ongoing stressors associated with the refugee and resettlement experience.

Innovations in Addressing Barriers to Care with Refugee Families and Children

Despite the potentially high need for psychosocial support among some refugee children and their families, refugee and immigrant youth are grossly underserved by mental health services (Ellis et al., 2010; Huang, Yu, & Ledsky, 2006; Munroe-Blum, Boyle, Offord, & Kates, 1989). Multiple barriers have been identified for refugee families and children in seeking assistance/care including difficulty in accessing services (e.g., transportation, health insurance), a paucity of available linguistically and culturally sensitive care, distrust of authorities and/or systems, stigma, differing cultural models of “mental health” and help seeking, and other priority needs (e.g., financial assistance, food insecurity) (Ellis, Miller, Baldwin, & Abdi, 2011; Kirmayer et al., 2011; Watters, 2001; Wong et al., 2006). Effective engagement of refugee children and families in mental health services thus requires innovations in where and in what manner mental health services are delivered. Innovations in mental health care of refugee children and their families include embedding comprehensive services into community and school settings, integrating cultural values and understandings into appropriate evidence-based practices, and building cultural knowledge and capacity within the larger workforce by both training providers in the needs of refugees as well as building capacity among refugees themselves to participate in providing mental health care (American Psychological Association (APA), 2010; Ellis et al., 2011; Lustig et al., 2004).

Trauma Systems Therapy for Refugees (TST-R) is a model of care that explicitly integrates these innovations, and has demonstrated success in engaging and treating young refugees. Ellis et al. (2011) initially developed the approach to specifically address a key problem they identified through their clinical experience and research with Somali refugee youth: Although a majority of these youth were exposed to high levels of trauma and many reported significant mental health symptoms, very few were receiving mental health care (Ellis, MacDonald, Lincoln, & Cabral, 2008). Parents and children both described a heavy stigma associated with “mental health” and traditional therapy services. Rather than seeking Western mental health treatment, most families sought help through traditional community supports such as family members and religious leaders (Ellis et al., 2010). In addition, both parents and adolescents identified schools as a trusted service system that could be turned to in times of need.

In this chapter, we describe the model and the ways in which it addresses critical barriers to engagement, and integrates evidenced-based trauma-informed care with an understanding of the specific socio-contextual needs and experiences of refugee youth and families.

Trauma Systems Therapy for Refugees

TST-R is an adaptation of Trauma Systems Therapy (TST) (Saxe, Ellis, & Kaplow, 2006; Saxe, Ellis, & Brown, 2015). TST is both an organizational model that guides the collaboration of care providers within service delivery systems to provide integrated treatment to traumatized children, as well as a clinical model that explicitly focuses on trauma-related emotional dysregulation. TST addresses a child’s “trauma system” based on the theory that children are impacted by both the emotional and neurobiological sequelae of trauma, as well as the stressors or reminders in their environment that can contribute to the exacerbation or maintenance of symptoms in the aftermath of traumatic events. TST emphasizes the importance of targeting both aspects of the trauma system through phased-based clinical intervention. In earlier phases of treatment where the child may demonstrate higher levels of dysregulation and where the social environment is less stable, more intensive, community-based care that focuses on safety and stabilization of a child’s environment is indicated. As a child progresses through the phases of treatment and their regulation and environment are correspondingly more stable, skill-building and trauma processing may be indicated.

TST as an organizational model seeks to provide integrated care. Organizational planning is a critical component of TST. At the inception of a TST/TST-R program, an organizational plan is developed that involves building partnerships across multiple disciplines and cultural backgrounds in order to provide the various levels and types of care needed across the different phases of treatment. This planning phase also includes a mapping of available resources, potential partners and strategies to identify potential funding/reimbursement mechanisms. It is a fundamental tenet of TST that a “formalized and well implemented” organizational plan that is endorsed by agency leaders is necessary to sufficiently support TST programs and team members (Saxe et al., 2015).

Initial trials of TST suggest that it is well tolerated and provide evidence that it significantly reduced PTSD symptoms, hospitalization rates, utilization of physical restraints, and significantly improved children’s capacity to regulate their emotions and behaviors (Brown, McCauley, Navalta, & Saxe, 2013; Saxe, Ellis, Fogler, Hansen, & Sorkin, 2005). Saxe et al. (2005) reported small to medium effect sizes (Cohen’s d = .18–.37) related to changes in PTSD symptoms, emotional and behavioral regulation, and the stability of the social environment. Since its development, TST has been disseminated and adapted for a variety of settings including outpatient mental health services, psychiatric residential settings, child welfare settings, and in dual treatment settings for trauma and substance abuse (Brown et al., 2013; Hidalgo, Maravić, Milet, & Beck, 2016). TST has demonstrated clinical and cost effectiveness (Ellis et al., 2011) as well as high levels of treatment retention (Saxe, Ellis, Fogler, & Navalta, 2012). In addition, implementing TST with fidelity in a Child Welfare system was associated with improvements in child well-being (functioning, emotional regulation, and behavioral regulation) and greater placement stability as indicated by the number of care placements a child received while in foster care (Moore et al., 2016).

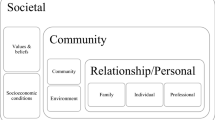

Although the theoretical framework of TST is well-suited to address the mental health needs of refugee children, adaptation of this model was necessary to address specific barriers to care in this population. Community engagement and stigma reduction were identified as essential components of developing a sustainable and acceptable intervention for resettled refugee community members. In addition, services were located within the schools to reduce barriers to accessing care and provide a more culturally acceptable context for help seeking. Within the schools, preventative groups offered to resettled refugee youth were an additional adaptation that provided an opportunity to further reduce stigma, engage youth and their families in services, and support the unique needs of refugee youth in the school setting. Lastly, the integration of cultural brokering was identified as an important adaptation to providing culturally sensitive services and building capacity among community members. The resulting model is a multi-tiered school-based intervention that integrates a public health approach to community engagement and stigma reduction with increasing levels of support at the higher tiers, with the highest being home-based TST safety-focused services (see Fig. 1; Model of Trauma Systems Therapy for Refugees). Across the four tiers of services, cultural brokers partner with mental health providers to deliver the intervention.

Cultural Brokering

According to Kaczorowski et al. (2011), delivering clinical services to refugees necessitates that clinicians develop cultural awareness and knowledge, as well as unique therapeutic skills. Moreover, research has shown that lack of cultural competence in the care system can be an important barrier to treatment engagement and adherence leading to negative outcomes (Barr, 2014; Carpenter-Song, Whitley, Lawson, Quimby, & Drake, 2011; Dixon et al., 2011). Traditionally, interpreters have been used to address cultural and linguistic barriers in health care, but creating culturally accessible care requires moving beyond linguistic interpretation. Culturally sensitive care must address the community/client’s distrust of mental health systems of care, stigma around mental illness, and providers’ lack of cultural knowledge so that they can tailor treatment approaches to a patient’s cultural understanding of the illness and treatment. To deliver mental health care that is culturally sensitive, providers must not only learn about the culture of patient populations and their health seeking practices, but providers and institutions must also conduct a self-examination to investigate how their assumptions and beliefs affect their interactions with and service provision to clients from different backgrounds.

One key innovation of TST-R is the integration of the role of a cultural broker into community engagement and clinical service delivery activities. Cultural brokering is defined as “the act of bridging, linking, or mediating between groups or persons of differing cultural backgrounds” (Goode, Sockalingam, & Snyder, 2004; Jezewski, 1990). This model provides an innovative approach to mental health care provision because cultural brokers work closely with both the provider/care system and the client with the purpose of facilitating communication, enhancing provider knowledge of patient’s culture and understanding of the illness, and improving the patient’s understanding of the health care system and the proposed treatment. Cultural brokers, therefore, are not a conduit of information between the provider and the patient but connectors whose role is to create a trusting relationship and a common purpose. Cultural brokering in TST-R incorporates both cultural competency, which focuses on increasing provider cultural awareness and knowledge (Kohn-Wood & Hooper, 2014), and cultural humility, a practice that encourages providers to practice critical self-awareness, self-evaluation, mutual respect, and to “say that they do not know when they do not know” in cross-cultural interactions (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998, p. 119). Ultimately, adding cultural brokering to mental health services creates a more culturally responsive service system, a more critically self-aware mental health workforce, and engaged, educated and empowered clients.

TST-R cultural brokers help to address key identified barriers such as stigma and resettlement stressors while also providing cultural and linguistic support to both clients and providers. Cultural brokers are integrated into all phases of the intervention and are considered integral members of the clinical team. The cultural broker holds cultural and system of care knowledge and plays a key role in the engagement of both community and individual clients, as well as the implementation of the intervention and building of cultural competency of providers. Cultural brokers are typically identified through working with community leaders and are often members of the community who already formally or informally act as helpers and liaisons within their culture.

Description of TST-R Model/Services

Tier 1: Community Engagement

The first tier of intervention in TST-R is community engagement. Community engagement focuses on reducing stigma and increasing education related to mental health needs and services. The development of TST-R was driven by principles of Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR), which emphasizes the importance of developing equal partnerships between academics and community members; the resulting research or, in this case, intervention is expected to be more culturally-informed and responsive to community-identified needs, and to build knowledge and capacity among both providers and community partners. An active community advisory board guided the initial implementation and subsequent adaptations of TST-R. The work with the advisory board established the importance of building strong community partnerships within each new community participating in subsequent implementations of the TST-R model. These community partnerships play a key role in community engagement and stigma reduction. Cultural brokers also play a central role in community engagement and education.

Tier 1 activities focus on creating an open and active dialogue with refugee community members. Community partners, cultural brokers, and/or staff members involved in TST-R services typically seek opportunities to participate in existing community activities (e.g., cultural fairs or education sessions), offer small groups for discussion in informal or formal settings, and engage parents through school-based activities (e.g., parent nights). Within these settings, discussions focus on understanding the concerns that refugee parents and community members have about their children’s development in their resettlement communities, stressors facing families, issues related to navigating the school systems and other services, and goals that community members have for their young people. Cultural brokers and clinical staff engage community members in this dialogue, offer resources or education as appropriate, and integrate into the discussion topics related to wellness, mental health, and the potential benefits of a program like TST-R. These discussions serve as a platform for the community to learn about the intervention and for the clinical team to learn about the community, address concerns, and integrate community input in the implementation. Throughout Tier 1 activities, care is taken to use language that is in line with the community’s cultural understanding of the issues. For example, given the stigma and different cultural concepts surrounding mental health, descriptive terms that are consistent with community members’ concerns and goals for their children (e.g., reducing stress, improving behavior, improving academic success, supporting families) are typically integrated into the discussion in lieu of western terms such as “mental health”, “depression”, or “PTSD.”

Community engagement also involves building partnerships and training service providers who work with refugees, particularly those in school and health/mental health systems.

Awareness of key refugee serving agencies, local culturally specific organizations, mental health and health providers, and school administration is an important aspect of organizational planning when developing a TST-R program. Identifying cultural brokers and other staff willing to engage flexibly with refugee communities is also essential. These partnerships are key to successful implementation of TST-R because refugees have a myriad of needs and face multiple barriers which one single agency cannot address. A more integrated service system and a workforce that is knowledgeable about the unique experiences and needs of refugees can mitigate key barriers such as lack of linguistic and cultural support and refugees’ lack of familiarity with Western service systems.

Tier 2: School-Based Groups

Based on feedback from community partners that acculturative stress was a significant concern, and that relationships between providers and families were best built in the context of non-stigmatized supportive services, a second tier of group-based services was included in TST-R. The groups offer a non-stigmatizing way to provide support to a broader range of refugee youth entering school systems. The goals of the groups are to support the acculturation of refugee children, while simultaneously providing them with social and emotion regulation skill building. The groups function as both a preventative intervention and an opportunity for screening those with mental health needs. TST-R cultural brokers act as co-leaders for the students in groups, but also as a connection to parents. Cultural brokers can play an important role in answering parents’ questions about the groups, maintaining ongoing contact, and building connections and trust with families.

The group curriculum is a 12-session manualized protocol that was originally developed for Somali middle school age students and co-led by a Somali cultural broker and school-based clinician (Abdi & Nisewaner, 2009; Nisewaner & Abdi, 2010). The curriculum is designed to be fun, interactive and activity-based. Given that boys and girls may have different experiences of the acculturation process and varying levels of comfort discussing their experience with children of the opposite gender due to their developmental stage or cultural expectations, groups are typically gender specific. When possible, they are offered to an entire class of incoming refugee students (e.g., 7th grade boys). In each session, students engage in a warm-up activity, group activity focused on a specific topic, discussion about this topic and how it relates to culture and the youth’s experiences, and a cool-down activity. The topics are not trauma specific, but instead focus on group cohesion and skill building. The topics include, but are not limited to verbal and nonverbal communication, similarities and differences, positive peer interactions, emotional identification and regulation skills, and conflict resolution. Special attention is paid to issues that immigrant and refugee youth struggle with, such as the process of navigating two or more cultures, dealing with peer conflict, effective communication skills and understanding emotions, and developing coping skills to manage daily stressors across different social environments. To date, the group curriculum has been implemented in multiple sites within the United States (U.S.) with Somali youth, and adapted and piloted with Bhutanese students and multi-cultural groups. Subsequent adaptations of the group manual have also included options for extending activities for younger and older age ranges.

Groups also serve as a means to connect youth who might need a higher level of care to clinical services in a culturally and linguistically appropriate manner. As children participate in the groups, group leaders develop relationships and build trust with parents and teachers by participating in school meetings with parents, connecting the family to additional services such as housing agencies or after school programs, facilitating parent/teacher communication and helping parents better understand how the American school system works. TST-R staff members, especially the cultural broker, thus become a bridge between school and refugee families whose children participate in the program. As a result, when children are identified as needing therapeutic mental health services, parents are already familiar with and may trust the program; this existing relationship often facilitates engaging parents in discussion around referral to TST-R individual therapy services.

Tiers 3 and 4: TST Clinical Services

While for many refugee students group work provides sufficient support, students with more specific trauma-related mental health problems may require more focused treatment. Within a TST-R program, these students may be identified through the groups or other sources of referral (e.g., teachers, parents); they are then referred to Tiers 3 and/or 4 of the program and receive TST therapeutic clinical services. TST clinical services can include: (1) skill-based therapy, (2) home-based care, (3) psychopharmacology, and (4) advocacy (Saxe et al., 2015). Students who present with dangerous emotions or behaviors (e.g., suicidality, physical aggression, poor judgment resulting in dangerous activities) and/or who live in social environments that are threatening (e.g., gang violence in neighborhood, domestic violence in the home) receive “safety-focused treatment”, or Tier 4. These services are typically home-based and include a partnership between a clinician and a cultural broker. Those students with sufficient stability to be assessed as safe, but who struggle with trauma-related dysregulation and/or significant stress in their social environments, receive “regulation focused” or “beyond trauma” phases of care (Tier 3), which are typically school-based.

In safety-focused treatment the goals of TST-R intervention are “to establish and maintain the safety and stability of the child’s social environment and to minimize the risk to the child and others based on the child’s difficulty regulating emotional and behavioral states” (Saxe et al., 2015, p.26). In TST-R, a cultural broker is paired with a clinician who is providing home-based services (Saxe et al., 2015). The cultural broker plays an important role in enhancing communication among family members and the clinician, attending to nonverbal and cultural cues, engaging the family, and facilitating clinical interventions. Even prior to beginning services, cultural brokers can help build the trust needed for refugee clients to invite strangers to their homes. Once a family accepts in-home services, the cultural broker can help clinicians by teaching them about the culture and what to expect during home visits. Additionally, cultural brokers work closely with outside providers (these often include child protection teams, school-based clinicians and community agencies) to ensure that there is service coordination and provide cultural lenses through which the family’s issues can be considered. Once services begin, cultural brokers work in partnership with clinicians to develop a language that would make sense to the client based on their cultural background. During visits, cultural brokers provide interpretation and cultural connection, helping the clinician and the family communicate in a meaningful way, while also using his/her cultural connection to the family to bridge the relationship. After encounters, cultural brokers and clinicians process what happened through an integrated clinical/cultural lens, therefore working to provide more integrated care and reduce misunderstandings.

Within safety-focused treatment, the cultural broker and clinician are working with families to identify collaborative goals focused on safety and stabilization. Systems advocacy plays an integral role in safety-focused treatment as it offers a mechanism and concrete tools for working on larger systemic problems that are fundamental contributors to a child’s dysregulation (Saxe et al., 2015). When working with refugee families, the importance of addressing concrete needs that may be contributing to threats or distress in the social environment, and therefore impacting the child, are central. Acculturation differences within families, which can lead to conflict and therefore stress in the social environment, are often a treatment focus that can be addressed through the collaborative work of clinicians and cultural brokers. Depending on how the roles of team members are established within service delivery systems, the cultural broker can also act as a case manager who attends to the identified stressors in the child and/or family’s environment such as housing or financial concerns. Attending to the primacy of these resettlement stressors is an important aspect of engaging refugee families, but also a means to identifying and reducing the stressors that may be most distressing to refugee families and children. In-home services are provided in lieu of, or in coordination with, a child’s individual therapy services. In both cases, the clinical team is focused on addressing priority problems in the child’s social environment that are impacting on their emotional and/or behavioral dysregulation. The child may still be receiving individual therapeutic support with some regulation-focused coping skills development. However within TST and TST-R safety-focused treatment, the importance of addressing external reminders or stressors/triggers that provoke a trauma response is recognized. For example, for a child living in an area with active community violence in which they feel threatened, TST focuses on establishing a safer environment for that child as the first priority.

When it is determined that a child is no longer experiencing dangerous survival states and that his or her environment is safe enough, the child is ready for Tier 3, or the regulation-focused or beyond trauma phases of treatment. In TST-R these phases are typically provided as school-based individual therapy focused on the development of coping skills to help the child learn new ways of self-regulating. Regulation focused treatment is provided by a clinician who may or may not involve a cultural broker in session, depending on the child’s and therapist’s language proficiencies. The primary goals of regulation-focused treatment are to help children develop emotion regulation capacities, identify ways caregivers can support this regulation, and to share this information with caregivers so that they can develop their own capacities to help and protect their children, therefore reducing or preventing their child’s switch to survival states (Saxe et al., 2015). Clinical strategies used in sessions focus on the concept of a trauma response, including identifying patterns of dysregulation in response to trauma triggers, reducing triggers when possible, and learning self-regulation skills to implement when reacting to trauma triggers. The understanding of these triggers and related intervention skills is constantly informed by cultural knowledge and/or cultural humility. The clinician is encouraged to be open to cultural aspects of emotion identification and coping skills and to integrate flexible ways of engaging refugee children (e.g., drawing or using pictures instead of relying on verbal communication). For example, some cultures/languages may have a limited range of vocabulary for describing emotions or ways of describing or expressing emotion that differ from the English language or the culture of the mental health provider. Role-playing and the discussion of somatic aspects of symptom expression are examples of tools that can further facilitate cross-cultural dialogue for the clinician and client. These skills are practiced with the therapist and shared with the child’s caregivers and clinical team.

The beyond trauma phase of treatment is an extension of this work, for children whose emotion regulation and social environment are more stabilized, that incorporates cognitive processing and restructuring skills and encourages the child to develop a trauma narrative. The primary goal of this phase of treatment is “to work with the child and family to gain sufficient perspective on the trauma experience so that the trauma no longer defines the child’s view of the self, world, and future,” (Saxe et al., 2015, p.26). In this phase of treatment, children work with their individual therapist to further develop coping skills, primarily related to building cognitive awareness and learning cognitive restructuring. For those with persistent trauma-related symptoms, developing a trauma narrative in a format that is appropriate to the child’s developmental and/or language capacity (e.g., writing a book, poetry, drawings, pretend play) and engagement in cognitive processing related to this narrative may be indicated. Given the history of multiple traumatic events in the lives of many refugee children, language/cultural differences, and the intergenerational trauma aspect of the refugee experience, trauma narratives may be flexible, creative, and reflect more of a timeline or narrative of the family migration experience as opposed to a focus on single traumatic incidents. The final stages of beyond trauma treatment aim to help children and families orient towards the future, set life goals, and nurture close relationships.

In the regulation-focused and beyond trauma phases of treatment (Tier 3) the cultural broker may participate in individual sessions when needed for language and cultural support. In this context s/he would serve as more than an interpreter of language, but also a source of cultural knowledge for both the clinician and the client, providing deeper context and cultural knowledge that enhances the understanding of the issues by all involved. Beyond involvement in individual treatment, cultural brokers can also facilitate parents’ interactions with school personnel and clinical staff, providing linguistic and cultural support as needed. Cultural brokers may also provide ongoing case management or facilitate contact with partner community services that can continue to attend to social environmental stressors for the child and family during these phases of treatment. The TST-R clinical team format provides an opportunity for cultural brokers to share their cultural and community knowledge with clinicians even when they are not providing direct services within individual therapy sessions.

Tiers 1–4 Organizational/Team Meetings

A weekly multidisciplinary team meeting inclusive of those partnerships identified during the organizational planning of the program is a critical aspect that ensures the smooth integration of systems and services across all tiers of care. As such, for all TST-R program staff, a weekly team meeting is held during which new and existing client cases are reviewed. Case discussions during the team meeting include a review of the background of the case, an assessment of the child’s current emotional or behavioral regulation status and social-environment, a determination of the phase of treatment based on this assessment, priority problems, targeted intervention approaches to address priority problems, and a discussion of cultural considerations. During the team meeting, the cultural broker(s) play an integral role in contributing information about engagement, cultural perceptions of the problems, related cultural or historical context, community knowledge, and strategies to enhance communication between families and providers.

Outcomes and Future Directions

TST-R was initially developed and implemented with Somali middle school youth (Ellis et al., 2013; Ellis et al., 2011). CBPR approaches to research within the Somali community guided community engagement activities and the adaptation of the TST model. The model was developed in partnership with school administrators, local community-based organizations, and mental health providers. The program was successful in engaging 100% (N = 30) of families who were referred for services (Ellis et al., 2013; Ellis et al., 2011). Preliminary findings from the first trial of this intervention demonstrated improvements in symptoms of PTSD and depression for children at all tiers of intervention and evidence that those with higher symptoms were appropriately matched with higher levels of care within this multi-tier model (Ellis et al., 2013). The outcomes also suggested an important role for the stabilization of social environmental stressors (resource hardships) in the reduction of mental health symptoms over time (Ellis et al., 2013).

Since this initial trial of the intervention, TST-R has been disseminated and piloted with Somali and Somali Bantu children and families in Maine, Kentucky, and Minnesota. The group intervention curriculum and TST-R intervention services were also adapted for, and implemented with, Bhutanese children and families in western Massachusetts. In each community, partnership development and community engagement has been an important element in determining the initial success and long term sustainability of the intervention. Initial evaluation findings from these dissemination projects suggest that the intervention is feasible, accepted, and viewed positively by students participating in services.

Strengths, Challenges, and Future Directions

TST-R is a unique prevention and intervention program that focuses on decreasing barriers to mental health care for refugee children and their families by providing integrated, multi-tiered approaches to intervention embedded within trusted service systems (i.e., schools). The strengths of this program include the flexibility in approaches to service delivery and an emphasis on community engagement and partnerships. Most importantly, services recognize the refugee experience and the importance of directly intervening in a child’s social environment to affect change. Further, the cultural broker role is an innovation that increases the capacity for programs to provide culturally and linguistically sensitive care, helps to build trust and engagement, and also increases the ability of services to directly intervene in a child’s family and community system. TST-R programs also have the potential to increase collaboration and efficiency across care delivery systems.

A recent sustainability study of TST-R dissemination sites identified several key elements that are important factors in developing this comprehensive program, including investment of key leadership within schools and community mental health organizations, a history of successful collaboration between key agencies, organizations, and/or refugee communities, a history of providing mental health providers services within schools, the size and organization of the refugee communities being served, and champions at the community and organizational level (Behrens, 2015). Given the complexity of the organizational readiness, partnership building, and community engagement that are essential to the success of this program, one of the greatest challenges of implementation can be identifying the funding to support the initial stages of program development.

Dissemination efforts have focused on identifying options for mapping services onto existing billing and mental health service structures within the U.S. mental health system. Funding and reimbursement for mental health services is variable by state within the U.S., and in some cases TST-R programs have advocated for state healthcare systems to fund certain aspects of the program. For example, in the state of Maine, home-based teams advocated to lift restrictions on the level of education required to fill a behavioral support position so that qualified refugee community members could serve as cultural brokers within this role designation for home-based TST-R teams. Although there is a growing recognition of the importance of comprehensive and preventative behavioral health interventions, there are aspects of the program that remain challenging to fund without the support of grants or philanthropy, particularly the cultural broker role and school-based groups. In some service systems this has been addressed by identifying ways to creatively bring together resources and existing roles (e.g., case management, school-based positions).

The initial stages of TST-R evaluation and implementation show promising efficacy in engaging refugee children and families with mental health services and reducing symptoms of distress in this traditionally underserved population. These promising outcomes suggest that this trauma-focused model is efficacious in meeting the needs of refugee children and families through innovative practice, including the integration of community engagement, cultural competency/cultural humility, cultural brokering, and tiered levels of school-based care. By incorporating these elements of service delivery, TST-R successfully addresses recommendations to tailor programs to the cultural needs of target populations and focus on more integrated, holistic models of care (APA, 2010; Kaczorowski et al., 2011). The knowledge gained from TST-R prevention and intervention efforts contributes to raising the standard of care for refugee children and families and informing responses to the ever-changing critical needs of new cultural populations seeking refuge and asylum.

References

Abdi, S. & Nisewaner, A. (2009). Group work with Somali youth manual. Unpublished manual.

American Psychological Association. (2010). Resilience & recovery after war: Refugee children and families in the United States. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/pi/families/refugees.aspx

Barr, D. A. (2014). Health disparities in the United States: Social class, race, ethnicity, and health. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Behrens, D. (2015). Financing Strategies for TST-R Project. Unpublished internal document, George Washington University.

Betancourt, T. S., & Khan, K. T. (2008). The mental health of children affected by armed conflict: Protective processes and pathways to resilience. International Review of Psychiatry, 20(3), 317–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260802090363

Bogic, M., Njoku, A., & Priebe, S. (2015). Long-term mental health of war-refugees: A systematic literature review. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 15(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-015-0064-9

Brewin, C. R., Andrews, B., & Valentine, J. D. (2000). Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(5), 748–766. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.68.5.748

Brown, A., McCauley, D., Navalta, K., & Saxe, C. (2013). Trauma systems therapy in residential settings: Improving emotion regulation and the social environment of traumatized children and youth in congregate care. Journal of Family Violence, 28(7), 693–703. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-013-9542-9

Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration. (2017). Fact sheet: Fiscal year 2016 refugee admissions. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/j/prm/releases/factsheets/2017/266365.htm

Carpenter-Song, E., Whitley, R., Lawson, W., Quimby, E., & Drake, R. E. (2011). Reducing disparities in mental health care: Suggestions from the Dartmouth–Howard collaboration. Community Mental Health Journal, 47(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-009-9233-4

Catani, C., Jacob, N., Schauer, E., Kohila, M., & Neuner, F. (2008). Family violence, war, and natural disasters: A study of the effect of extreme stress on children’s mental health in Sri Lanka. BMC Psychiatry, 8(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244x-8-33

Dixon, L., Lewis-Fernandez, R., Goldman, H., Interian, A., Michaels, A., & Kiley, M. C. (2011). Adherence disparities in mental health: Opportunities and challenges. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 199(10), 815–820. https://doi.org/10.1097/nmd.0b013e31822fed17

Ellis, B. H., Lincoln, A. K., Charney, M. E., Ford-Paz, R., Benson, M., & Strunin, L. (2010). Mental health service utilization of Somali adolescents: Religion, community, and school as gateways to healing. Transcultural Psychiatry, 47(5), 789–811. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461510379933

Ellis, B. H., MacDonald, H. Z., Lincoln, A. K., & Cabral, H. J. (2008). Mental health of Somali adolescent refugees: The role of trauma, stress, and perceived discrimination. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(2), 184–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.76.2.184

Ellis, B. H., Miller, A. B., Abdi, S., Barrett, C., Blood, E. A., & Betancourt, T. S. (2013). Multi-tier mental health program for refugee youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(1), 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029844

Ellis, B. H., Miller, A. B., Baldwin, H., & Abdi, S. (2011). New directions in refugee youth mental health services: Overcoming barriers to engagement. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 4(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361521.2011.545047

Fazel, M., & Stein, A. (2002). The mental health of refugee children. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 87(5), 366–370. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.87.5.366

Goode, T. D., Sockalingam, S., & Snyder, L. L. (2004). Bridging the cultural divide in health care settings: The essential role of cultural broker programs. Washington, DC: National Center for Cultural Competence.

Hidalgo, J., Maravić, M., Milet, C., & Beck, R. (2016). Promoting collaborative relationships in residential care of vulnerable and traumatized youth: A playfulness approach integrated with trauma systems therapy. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 9(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-015-0076-6

Huang, Z., Yu, S., & Ledsky, R. (2006). Health status and health service access and use among children in U.S. immigrant families. American Journal of Public Health, 96(4), 634–640. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2004.049791

Jezewski, M. A. (1990). Culture brokering in migrant farm worker health care. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 12(4), 497–513. https://doi.org/10.1177/019394599001200406

Kaczorowski, J. A., Williams, A. S., Smith, T. F., Fallah, N., Mendez, J. L., & Nelson–Gray, R. (2011). Adapting clinical services to accommodate needs of refugee populations. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 42(5), 361–367. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025022

Khawaja, N. G., White, K. M., Schweitzer, R., & Greenslade, J. (2008). Difficulties and coping strategies of Sudanese refugees: A qualitative approach. Transcultural Psychiatry, 45(3), 489–512. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461508094678

Kirmayer, L. J., Narasiah, L., Munoz, M., Rashid, M., Ryder, A. G., Guzder, J., et al. (2011). Common mental health problems in immigrants and refugees: General approach in primary care. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 183(12), E959–E967. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.090292

Kohn-Wood, L. P., & Hooper, L. M. (2014). Cultural competency, culturally tailored care, and the primary care setting: Possible solutions to reduce racial/ethnic disparities in mental health care. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 36(2), 173–188. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.36.2.d73h217l81tg6uv3

Lustig, S. L., Kia-Keating, M., Knight, W. G., Geltman, P., Ellis, H., Kinzie, J. D., … Saxe, G. N. (2004). Review of child and adolescent refugee mental health. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(1), 24–36. https://doi.org/10.1037/e318832004-001

Moore, K. A., Redd, Z., Beltz, M., Malm, K., Murphy, K., Schusterman, G., & Sticklor, L. (2016). KVC’s bridging the way home: An innovative approach to the application of trauma system therapy in shild welfare.. Lexington, KY: KVC Health Systems.

Munroe-Blum, H., Boyle, M., Offord, D., & Kates, N. (1989). Immigrant children: Psychiatric disorder, school performance, and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 59(4), 510–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.1989.tb02740.x

Nisewaner, A., & Abdi, S. M. (2010, June). Challenges, strategies and rewards of an adaptation of trauma systems therapy for newly arriving refugee youth: School-based group work with Somali adolescent boys. In V. Roy, G. Berteau, & S. Genest-Dufault (Eds.), Strengthening Social Solidarity through Group Work: Research and Creative Practice. Paper presented at the Proceeding of the XXXII International Symposium on Social Work with Groups, Montreal, June 3–6, (pp.129–147). London, UK: Whiting & Birch.

Office of Refugee Resettlement. (2016). Unaccompanied children released to sponsors by state. Retrieved from: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/orr/programs/ucs/state-by-state-uc-placed-sponsors

Reed, R. V., Fazel, M., Jones, L., Panter-Brick, C., & Stein, A. (2012). Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in low-income and middle-income countries: Risk and protective factors. The Lancet, 379(9812), 250–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60050-0

Saxe, G. N., Ellis, B. H., & Brown, A. D. (2015). Trauma systems therapy for children and teens (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford.

Saxe, G. N., Ellis, B. H., Fogler, J., Hansen, S., & Sorkin, B. (2005). Comprehensive care for traumatized children: An open trial examines treatment—Using trauma systems therapy. Psychiatric Annals, 35(5), 443–448. https://doi.org/10.3928/00485713-20050501-10

Saxe, G. N., Ellis, B. H., & Kaplow, J. (2006). Collaborative care for traumatized teens and children: A trauma systems therapy approach. New York, NY: Guilford.

Saxe, G. N., Ellis, H. B., Fogler, J., & Navalta, C. P. (2012). Innovations in practice: Preliminary evidence for effective family engagement in treatment for child traumatic stress–trauma systems therapy approach to preventing dropout. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 17(1), 58–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2011.00626.x

Sundquist, J., Bayard-Burfield, L., Johansson, L. M., & Johansson, S. E. (2000). Impact of ethnicity, violence and acculturation on displaced migrants: Psychological distress and psychosomatic complaints among refugees in Sweden. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 188(6), 357–365. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-200006000-00006

Tervalon, M., & Murray-Garcia, J. (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 9(2), 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2010.0233

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2015). UNHCR global trends 2015: Forced displacement in 2015. Retrieved from: https://s3.amazonaws.com/unhcrsharedmedia/2016/2016-06-20-global-trends/2016-06-14-Global-Trends-2015.pdf

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2016). Facts and figures about refugees. Retrieved from: http://www.unhcr.ie/about-unhcr/facts-and-figures-about-refugees

Watters, C. (2001). Emerging paradigms in the mental health care of refugees. Social Science & Medicine, 52(11), 1709–1718. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00284-7

Wong, E. C., Marshall, G. N., Schell, T. L., Elliott, M. N., Hambarsoomians, K., Chun, C. A., & Berthold, S. M. (2006). Barriers to mental health care utilization for US Cambodian refugees. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(6), 1116–1120. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.74.6.1116

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Benson, M.A., Abdi, S.M., Miller, A.B., Heidi Ellis, B. (2018). Trauma Systems Therapy for Refugee Children and Families. In: Morina, N., Nickerson, A. (eds) Mental Health of Refugee and Conflict-Affected Populations. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97046-2_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97046-2_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-97045-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-97046-2

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)