Abstract

The functioning of the organization is related to the implementation of its mission and vision and the pursuit of specific goals set in the strategy. Regardless of the branch of production, sector of service or public administration, the strategy defining aims to be achieved and indicating the manner of their implementation it determines the path of development and survival in the turbulent times of change. The formal structure of the organization is also related to the functioning of the organization, regulating the level of dependence between the units inside it, creating a network of mutual connections in the form of an organizational scheme. The publication covers the features of the strategy as an obligatory document for public higher education institutions and the types and functions of the organizational structure specific to the sector of higher education in Poland. The article will present the relationships that occur between the organization’s strategy and its structure in the area of higher education in Poland. The authors will seek answers to the question which of the two-factor system in public universities is an element that is more often subject to changes and whether the change of one of them always involves updating the other.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

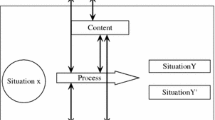

By definition, each organisation is created by a certain group of people in order to achieve a shared goal. Goals are attainable when rational, measurable, adequate to a situation, determined in time and defined in a structured way. In each formally defined organisation operating in a rational way a set of objectives is determined as an action plan, which most often is then formed into a strategy. It is natural for most organisations that when assigning a set of objectives, they adjusts to them the structure of the internal processes thanks to which the objectives can be achieved. A demand for human resources emerges based on such a structure of processes. In order for an organisation to function in a correct way the roles of authority have to be correctly defined and realised. Authority is inseparably associated with the notion of hierarchical relationships. Thus the notion of organisational structure emerges. A correctly developed organisational structure should assure full compatibility, convergence and harmony of both the individual and the group objectives [1]. Accordingly, the organisational structure is a formal mapping of dependencies – reporting lines within the organisation. The mapping defines responsibilities, issuing commands as well as enforcement of task performance. In most economic organisations the relation between strategy, process mapping and organisational structure is determined in a clear and correct way according to the following order: first the strategy, then, on its basis, the structure of processes and only in the end (as a response to the human resources demand) an employment structure is determined. Yet it has to be kept in mind that economic organisations, i.e. the ones that have a clearly determined ownership structure and economic objective (most frequently associated with bringing profit to the owner or a group of owners) function slightly differently than the organisations that do not operate for the profit sake. A public university of technology, an example of an organisation that does not operate for profit, will be used as a case study in the article. The aim of a public higher education institution (HEI) is not work for profit but for development [2]. The specific character of this type of organisations enforces a slightly different method of defining a strategy [3] and building an organisational structure, based to a larger extent on academic tradition rather than on the rules emerging from the art of management.

Therefore building of both the strategy and the organisational structure is based on different paradigms and needs than rational premises resulting from the rules of management. A problematic issue in case of this organisation type is that it is difficult to define the entity performing the role of the owner and the role of the managing individual [4]. As a consequence the strategy is based on objectives that are not directly close to the organisation itself but they rather result from internal regulations and arrangements oriented towards achieving individual aims of internal entities in the organisation and some unspecified entities among external stakeholders. The entities influencing strategic goals include representatives of local governments, state government administration, business, community, applicants for studies and alumni. There exists a significant problem with distinguishing whether a strategy is based on rational premises favourable to the development of a given academic community and the region in which it operates. Hence it is difficult to clearly determine if a strategy is appropriate for further development of the organisation. The more it is problematic to detect to whom the university authorities report as to the owner. These difficulties with specifying the adequacy of the strategy to the needs of the university itself and of the region find reflection in the difficulties associated with construction of the organisation’s internal structure. The research performed by the authors for a group of technical universities in Poland indicates that in most cases it is possible to observe a phenomenon of creating at universities structures based on the needs of their staff rather than on the needs resulting from the organisations’ strategy. These needs of the staff include first of all the demand to maintain employment, which is supported and promoted by their direct superiors, who, in turn, are subordinates to their higher superiors. It is a frequent situation at universities that the predominant goal of their employees is not to compete with the outside entities (opposite to economic organisations) but to maintain the employment as the very aim in itself. Such an approach appears to be wrong only when looked at from the outside of the organisations. The university community itself is unable to identify such situations as risky for further existence of the university.

In order to assess the scale of the above phenomenon the authors present the way a strategy was developed and evolves and mechanisms with which the employment structure gets associated with the strategy. The research proved that the most common motivation for elaborating a strategy is not the internal need for the organisation development but the requirement of legislation. As a consequence the organisation structure functions irrespective of the strategy. Yet these relationships are not clear, which means that it is hardly possible to determine whether there exists this strict relationship or if there is no connection at all. Most commonly the reality appears to exist in between these two extremities. The article presents the results of investigations in this area.

2 Research Method

A university of technology, with over 70 years of academic tradition, occupying leading positions in Polish higher education rankings was selected to be the object of the research. The research method is based on an insightful analysis of accessible documented information on the University structure and strategy. The article presents organisation structure of the selected HEI and the results of the overview of its strategic documents. The authors carried out the analysis of the above aspects in the selected university (as they developed in time) in the period of the recent twenty five years. All internal normative acts collected in the resources of the computer network of the university, including archival documents, were identified. Identification, analysis and in-depth study of these documents enabled to the authors formulating final conclusions and proposing improvement actions.

3 Results of Analysis

3.1 Strategy Analysis on the Basis of Internal Normative Acts

In the university’s over 70 years history the earliest documented form of a strategy could be traced back as late as 25 years ago. The strategic document known as “the programme” was elaborated following the external legislation [5]. The first source document contains goals referring to the areas of university activities, at that time identified as the main ones, such as education, science and staff development. To a large extent the above refers to the role and mission of a University as described in the report on higher education [6], which is actually perceived positive by the authors. Yet in the original strategy the goals remain characterised by significant generalisation with no directions and no persons responsible for achieving the enumerated goals. As a result the strategy is impossible both to realise and to evaluate. However the original document refers to modifications in the management structure, from a centralised one to a decentralised one. In the opinion of early authorities the act of handing over the financial, infrastructure and human resources management processes to faculties served to support the achievement of the main strategic goals standing in front of the university.

Yet the above found no mapping in the strategy document. It has to be noticed at this point that in the analysed organisation the basic organisational units (faculties) were the ones that ought to concentrate their activities around common, university goals. Still the authors do not analyse the internal structure on the central administration level. The history of changes of the strategic document adopted by the outgoing authorities suggests maintaining the programme “General development strategy” by the newly elected management bodies of the university. This situation clearly indicates the fact of continuation of the approved strategic goals, which again is positive. Yet the new strategy sets new tasks for realisation in particular areas (teaching, science, organisation and finances, as well as campus location issues). It has been noticed that the originally approved strategy did not specify time frameworks for realisation of strategic goals. Until the moment of elaborating a new update to the strategy the university published its mission in a separate document. The organisation mission, being the reflection of its vision [7] is the most important strategic communication [8], which makes it necessary to be published before the strategy or to become its integral part. After nine years the strategic programme underwent a thorough reconstruction and was published as the document entitled “Strategy: directions of development for the years 2008–2020”. In its first part the document contains “Programme of the University development”, and in the second part the mission, the vision, the goals and priorities can be differentiated. The strategy, elaborated under a statutory obligation [9], develops six adopted specific objectives into priorities that can be balanced by the tasks for realisation. Still the authors observed lack of time-frameworks and assignment of responsibilities as far as achieving of the set goals is concerned, which invariably makes the strategy inefficient for realisation and impossible to verify.

A presumption should be made that these reasons led to modification of the document after seven years and to transforming it into “Strategy of the University development for the years 2015–2020”, a document abiding to this day. The strategy currently functioning in the analysed university embraces 5-year time horizon, hierarchical structure of goals and determination of terms and units responsible for their realisation. 5 main strategic goals can be enumerated, each of them divided into a number of operational objectives. In order to realise altogether 34 operational objectives 136 activities were differentiated, for each of them a responsible person as well as the value indicator to be achieved in 5-year time horizon were assigned. Heads of units as well as the main authorities, i.e. the Rector, and Vice-rectors managing the units reporting to specific organisational divisions are responsible for realisation of particular activities. Implementation of the approved strategy and evaluation of the achieved results [10] are equally important in the process of the university strategic management as formulating the development strategy itself. Obtaining the university goals determined in the strategy becomes realistic, assuming that the activities are supported by appropriate assignment of duties and responsibilities of the staff in the organisational structure [11].

3.2 Evaluation of the Organisational Structure Variability

The timelines in which both the approved strategy of the university and the structure were evaluated can be symbolically divided into three periods. In years 1992–2000 the organisation structure was four times a subject to changes, each time altering basic organisational unit’s structure. In this period the organisation structure was not correlated with the strategy approved by the authorities and did not refer to it in any way. Together with the strategy determined in a generic way the structure was a separate element in terms of goals realised by the university. In the second period, including the years 2001–2008, the organisational structure was sustained. It is considerably puzzling that both the organisational structure and the strategy remained unchanged in that time period. Supposedly the university authorities did not correlate a possibility to achieve the approved goals with a properly selected organisational structure, hence the lack of visible changes in both the aspects. The years 2008–2017 were the time of turbulent changes in the field of the university organisation. The functioning scheme for particular divisions and units was changed eight times. In this period petrification of structure was observed for basic organisational units with subsequent changes in central administration. The above is the consequence of the university decentralising carried out a few years earlier, which resulted in strengthening the role of faculty as the basic organisational unit supervising all subordinate resources, including human resources, infrastructure and finances. Organisational scheme from this period included eight updates, out of which three were convergent with the term of inauguration of a new academic year, which clearly indicates that organisation structure is treated as a tool in the hands of the university authorities for creating a system of areas, divisions and units following an intention of a selected managing group. This situation brings about the risk of performing changes in structure each time a new term of office is inaugurated and whenever a newly elected rector plans realising the objectives assigned by him/her with the use of an appropriate organisational system. When analysing the structure in the selected university during the recent ten years, changes in administration area were observed. The authors noticed creating and cancelling of particular units and of independent positions and changes of organisational subordination. In the authors’ opinion these modifications result from changeability of the environment, including other competitive universities, and they should be perceived positively as an adjustment to turbulent elements of the external environment. Yet simultaneously the changes in subordination of particular units to a different organisational division disturb the possibility to achieve the objectives attributed to specific vice-rectors. Analogously to the previous versions of organisational structure, the current one turns out subjected to the tasks realised by the university authorities but remains incompatible with the functioning strategy.

3.3 Relationships Between Strategy and Organisational Structure on the Example of a Public University of Technology

In case of the analysed public university tracing the changes that have taken place during the recent 25 years in the area of HEI strategy and structure leads to the following conclusions:

-

In HEIs lack of coherence is observed between the strategy document and organisational structure; in the university of technology studied as a sample these two elements constitute two separate aspects not supporting each other;

-

In the analysed period of time the strategy of the sample university underwent 3 transformations, while its organisational structure was changed 12 times; which implies that the organisational structure is applied as the means of a temporary management of the organisation, and the strategy is at the same time perceived as a lasting, long-term document;

-

The structure of a public university is an element subjected to changes four times more often than its strategy; this may indicate the use of organisational structure as a form of exercising power without the awareness what consequences such changes bring for the organisation;

-

In spite of expanding operational objectives and providing the path for activities together with the deadlines for their realisation, evolution of the university strategic document is not supported by accordingly updated organisational structure; these two pillars of organisation management function somehow separately, not supporting each other;

-

Change of organisational structure was not convergent with the date of publishing a new issue of the strategy; this clearly indicates the fact that the University authorities are not conscious of the possibility or rather necessity to support strategy realisation by a proper structure of the organisation;

-

Four times the change of organisational structure is convergent with the inauguration of the academic year, simultaneously in four cases marking the commencement of a new term of office of the academic authorities; this situation reinforces the authors’ conviction that term-elected authorities use the organisational structure as the element of management;

-

Strategy is a static element at the university in relation to the structure, which in turn becomes a dynamic element of the organisation; thus the organisational structure does not support the realisation of the approved tasks.

Summary of the inferences drawn from the research leads to conclusions that the University authorities develop a strategy due to external conditions, in particular the legal ones, at the same time wishing to maintain the system of work positions existing so far. Organisational structure, as the element most frequently undergoing changes, is not perceived as facilitating realisation of strategy [12]. Whereas a change in the field of structure is a manifestation of power to introduce new organisational solutions in accordance with the vision of the university represented by the university authorities or by other decisive groups [10].

4 Summary

The existence of relations between strategy and structure in a HEI is not equivalent to proven relations and influence of strategy on structure in production enterprises [13]. This theory, repeatedly confirmed by scientists, sets strategy as the basic determinant of structure [12, 14]. On the basis of the quoted research results variability of one factor in relation to the other is clearly visible. In the field of higher education it is the strategy that turned out to be the element prone to demonstrate inertia, whereas organisational structure changes with a significant frequency in relation to the approved strategy. The lack of coherence between organisational structure and strategy of a HEI is clearly visible. If a structure does not support strategy, basing on Chandler’s theory [13], it can be implied that lack of support for strategy by the university structure can lower efficiency of HEI’s activities. The final conclusion of the considerations brings about the suggestion that in order for a strategy in a HEI to fulfil its purpose (i.e. to lead to achievement of the set goals), that strategy should be supported by HEI organisational structure. Following the statement by Drucker, regardless of organisational differences, it is the mission that, above all other elements, should determine the strategy, and the strategy should determine the structure [15]. Otherwise the strategy becomes a dead element that does not fulfil the main task, which is to achieve the advantage over competition through the increase of efficiency and increase of confidence in acting and mobilising all resources to achieve the set goals [16,17,18]. The realised activities aiming at achieving the objectives on the operational level are not supported by the organisational structure. Whereas the organisational structure becomes a tool in the hands governing the university. Yet undoubtedly with the use of structure organisations’ authorities do not realise the approved university strategy but instead they aim at achieving the aims elaborated by themselves. The authors of the article made the attempt to indicate the reasons behind this situation, yet not all factors determining this relations have been identified. At this stage of considerations the question about the lack of close relationship between strategy and structure in organisation should be posed to any rector managing a public university.

References

Bieniok, H., Rokita, J.: Organizational Structure of the Company. Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Warszawa (1984)

Geryk, M.: Complexity Management Processes of Higher Education Institutions and their Impact on the Value of Institutions as One of Measurement Performance Management. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego. Finanse, Rynki Finansowe, Ubezpieczenia, vol. 64, pp. 127–134 (2013)

Kisielnicki, J.: Management: How to Manage and be Managed. Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne, Warszawa (2008)

Leja K.: What is the authority of the rector of a public university? E-mentor, 5(32) (2009)

Law on Higher Education: The Act of September 12, 1990 on Higher Education

du Valla M.: Final report “Models of university management in Poland”. Uniwersytet Jagielloński Centrum Badań nad Szkolnictwem Wyższym, Kraków (2011)

Jemielniak, D., Latusek-Jurczak, D.: Management: Theory and Practice in a Nutshell. Wydawnictwo Poltext, Warszawa (2014)

Koźmiński, A.K., Jemielniak, D.: Management from Scratch. Academic Handbook. Wydawnictwo Akademickie i Profesjonalne Spółka, Warszawa (2008)

Law on Higher Education: The Act of July 27, 2005 on Higher Education

Wawak T.: Pro-quality strategic management in higher education in crisis conditions. In: Stabryła, A. (ed.) Concepts of Managing a Modern Enterprise, pp. 13–25. Fundacja Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego. Kraków (2010)

Pierścionek, Z.: Strategic Management in the Enterprise. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa (2011)

Griffin, R.W.: Basics of Organization Management. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa (2006)

Chandler, A.: Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise. The MIT Press, Cambrigde (1962)

Zakrzewska-Bielawska, A.: Strategy as a factor determining the organizational structure of the enterprise. In: Stabryła, A. (ed.) Improving Management Systems in an Information Company, pp. 499–508. Wydawnictwo AE, Kraków (2006)

Drucker P.F.: Drucker’s Thoughts. Wydawnictwo MT Biznes, Warszawa (2002)

Marchesnay, M.: Strategic Management. Poltext, Warszawa (1994)

Sigismund, Huff A., Floyd, S.W., Sherman, H.D., Terjesen, S.: Strategic Management. Resource Approach. Wolters Kluwer Business, Warszawa (2011)

Hammer, M., Champy, J.: Reengineering in the Enterprise. Neuman Management Institute, Warszawa (1996)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this paper

Cite this paper

Mnich, J., Wisniewski, Z. (2019). Strategy and Structure in Public Organization. In: Kantola, J.I., Nazir, S., Barath, T. (eds) Advances in Human Factors, Business Management and Society. AHFE 2018. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol 783. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94709-9_33

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94709-9_33

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-94708-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-94709-9

eBook Packages: EngineeringEngineering (R0)