Abstract

We investigate determinants of individual migration decisions in Vietnam, a country with increasingly high levels of geographical labour mobility. Using data from the Vietnam Household Living Standards Survey 2012 (VHLSS2012), we find that the probability of migration is strongly associated with individual, household and community-level characteristics. The probability of migration is higher for young people and those with post-secondary education. Migrants are more likely to be from households with better-educated household heads, female-headed households, and households with higher youth dependency ratios. Members of ethnic minority groups are much less likely to migrate, other things being equal. Using multinomial logit methods, we distinguish migration by broad destination, and find that those moving to Ho Chi Minh City or Hanoi have broadly similar characteristics and drivers of migration as those moving to other destinations. We also use the VHLSS2012 together with the VHLSS2010, which allows us to focus on a narrow cohort of recent migrants—those present in the household in 2010, but who had moved away by 2012. This yields much tighter results. For education below upper secondary school, the evidence on positive selection by education is much stronger. However, the ethnic minority “penalty” on spatial labor mobility remains strong and significant, even after controlling for specific characteristics of households and communes. This lack of mobility is a leading candidate to explain the distinctive persistence of poverty among Vietnam’s ethnic minority populations, even as national poverty has sharply diminished.

A previous version of this paper was circulated as ‘Migration in Vietnam: New Evidence from Recent Surveys’, World Bank Group, Vietnam Country Office, World Bank Development Economics Discussion Paper No. 2, July 2015. The views expressed in this chapter are the authors’ alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the World Bank or its Executive Directors.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

JEL Classification

Keywords

1 Introduction

Internal migration is a standard and prominent feature of every low–middle-income country, and especially of those undergoing rapid growth and structural change. Growth rates are highly unequal across broad industries and, since industries are unequally distributed across space, unbalanced growth creates incentives for labour to move. Thus, changing patterns of labour demand align with one of the main objectives of migration, which is to increase and stabilise the incomes of migrants as well as those of their origin households (Stark and Bloom 1985; Stark and Taylor 1991; Stark 1991; Borjas 2005).

Economists as well as policymakers have long been interested in understanding the causes of migration. There are many perspectives on the migration decisions of individuals or households. In conventional theory, individuals relocate to maximise utility given spatial variation in wage and price levels (Molloy et al. 2011; Valencia 2008). In the New Economics of Labour Migration, decisions to migrate depend on characteristics of both migrants and their families (Stark and Bloom 1985; Stark and Taylor 1991). The amenities and/or community characteristics of home and destination locations are also considered to be important factors exerting ‘push’ and ‘pull’ forces on migrants (Mayda 2007; Kim and Cohen 2010; Ackah and Medvedev 2012), or limiting outmigration through attachment to place-specific kinship or cultural attributes (Dahl and Sorenson 2010). Social factors are known to be important because the ‘trigger price’ for migration—that is, the expected income differential between origin and destination—is always found to be much larger than the simple financial cost of relocating (Davies et al. 2001). More recently still, global climate change has been responsible for creating differences among locations. Some areas that were once well suited to particular forms of agriculture are now vulnerable to drought or other adverse conditions. Changes in agricultural yields were found to influence migration rates in a study of US counties (Feng et al. 2012). Tropical areas are experiencing increased susceptibility to storms, saline intrusion and flooding, and these environmental factors may be increasingly influential as drivers of migration in the future.

Labour mobility improves the efficiency with which workers are matched with jobs. This contributes to an increase in net income both for individuals and for the economy as a whole. Labour migration is a special case of spatial labour mobility, typically from locations where capital and other factors that raise labour productivity are scarce to locations where they are more abundant. Remittances are a mechanism for redistributing the net gains from increased spatial labour mobility. They spread these gains from migrants to the population at large (McKenzie and Sasin 2007). Since migration is usually from regions in which labour productivity (and hence low per capita income) is low to regions where it is high, remittances typically contribute to poverty alleviation (e.g. Adams and Page 2005; Acosta et al. 2007).

Vietnam’s rapid economic growth has been accompanied—as in many other parts of the developing world—by increasingly high levels of geographical labour mobility. While international migration is significant, most migrants still move within the country—and indeed, most go to a relatively small number of internal destinations. Vietnam is small and geographically compact relative to many other well-studied developing countries. From Da Nang, in the centre of the country, to either of the two major cities (Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City) is less than 800 km, or 14–16 hours by bus. Relatively short distances, coupled with near-universal access to mobile phones, mean that contemporary migration is much less costly and risky than in many other countries or in Vietnam’s own past. Potential migrants can learn about job opportunities, resettlement costs, and other important considerations in destination cities before deciding on a move. In this setting, there is likely to be very little Harris and Todaro (1970) style speculative migration accompanied by urban unemployment. Unemployment in destination markets is more likely to be frictional than structural.

Economic growth and lower migration costs have been associated with large increases in migration. Vietnam’s 1989 Census recorded very few internal migrants; the majority came from one rural location to another and their motives for relocating were a mix of economic and other factors (Dang 1999).Footnote 1 This changed quickly as economic growth accelerated in the 1990s. According to the 1999 Census, 4.5 million people changed location in the 5-year interval 1994–1999. By this time, the economic reform era was well under way, and the surge in spontaneous migration was also driven far more explicitly by income differentials (Phan and Coxhead 2010). By the next census, in 2009, this 5-year migration figure had increased by almost 50%, to 6.6 million (Marx and Fleischer 2010), or almost 8% of the total population. Again, a large fraction of those who moved did so for economic reasons. Vietnam’s economic growth since the early 1990s has been dominated by secondary and tertiary sectors, with a big contribution from foreign investment and the reform of state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Changes in the sectoral and institutional structures of labour demand have mirrored these trends (McCaig and Pavcnik 2013). Growth of employment and labour productivity in Vietnam is overwhelmingly in nonfarm industries and urban areas.

Moving to where job prospects and earnings growth are higher is sensible for most individuals, subject to cultural and behavioural norms, transaction costs and other constraints. Promoting labour mobility and remittances is also in general good development policy. Therefore, understanding the drivers of migration and remittances is an input to policy recommendations for development. The main objective of this research is to investigate the dynamics of the individual migration decision in Vietnam.

There have been many studies of internal migration in Vietnam (Guest 1998; Djamba et al. 1999; Dang et al. 1997, 2003; Dang 2001a, b; GSO and UNFPA 2005; Cu 2005; Dang and Nguyen 2006; Nguyen et al. 2008, 2015; Tu et al. 2008; Phan 2012). However, the Vietnamese economy continues to grow and develop apace, and the domestic labour market is one of the key conduits for structural change. From 2005 to 2013, urban employment in Vietnam grew by 45%, rising from about one-quarter of jobs to nearly one-third. Meanwhile, rural employment expanded by only 14% (data from gso.gov.vn, accessed 5 July 2015). Foreign investment, much of which goes into labour-intensive manufacturing enterprises located in urban and peri-urban industrial zones, surged after Vietnam’s World Trade Organisation (WTO) accession in 2007. Moreover, government policies affecting labour demand and supply, including migration decisions, have also evolved—in particular, the previously strong emphasis on the ho khau (residence certificate)Footnote 2 as a prerequisite for working in cities has diminished considerably. Institutional barriers to migration (for example, land tenure security and access to credit) are also changing, albeit more slowly. Taken together, these trends provide good reason to regularly revisit migration trends and associated labour market developments as new data become available. We have an opportunity to gain perspective through comparisons with findings from earlier studies and to contribute to the design and evaluation of labour and social policy for the near future.

Our chapter fits within a familiar tradition, yet it differs from earlier work in several respects. First, we examine factors associated with different types of migration, including migration for work and non-work purposes, and migration with different choices of location. Second, we use the most recent available data, from the nationally representative VHLSS2010 and VHLSS2012. The VHLSS2012 in particular contains a special module on migration, with extensive data on both migrants and sending households. Thus, the results of the study will help identify factors influencing migration decisions at the national as well as regional levels.

The rest of the chapter is structured as follows. The next section briefly reviews the relevant literature. Section 3 discusses the data used in this study. Section 4 presents migration patterns in Vietnam. Sections 5 and 6 present the estimation method and empirical results of determinants of migration, respectively. The final section concludes the analysis.

2 Migration Choices: A Review of the Literature

Traditional migration models link migration decisions with ‘pull’ and ‘push’ factors. Pull factors are destination-specific incentives such as job opportunities and higher real wages. Push factors at the place of origin cause outmigration. This ‘disequilibrium’ view of migration emphasises persistent expected income differentials as a major motivation for migration. The New Economics of Labour Migration (Stark and Bloom 1985) broadens this approach by regarding migration decisions as household-level resource allocation decisions, taken to maximise household utility and minimise variability in household income. Recent research tries to identify factors behind migration, considering market failures due to information asymmetries, credit market imperfections and network effects.

There are two top-level approaches to estimation of migration propensity: descriptive (based on an ex post model such as the gravity equation) and behavioural (e.g. based on an ex ante model such as utility maximisation). Though the two are not mutually exclusive, most empirical migration models start from either one or the other. Behavioural models make use of microdata such as surveys of individuals or households, while gravity models appeal to the representative agent assumption and make use of aggregate data—for example, census data in which migration rates are measured at the level of the community or administrative unit (Phan and Coxhead 2010; Etzo 2010; Huynh and Walter 2012).

The ex ante approach typically starts from a utility function and derives an estimating model that measures the propensity to migrate. In the case of household decisions, migration can be seen as portfolio diversification—for example, in response to uninsurable risk in farming. In these models, the migrant must implicitly be considered as a continuing household member, at least for the purposes of remittances and/or emergency gifts.Footnote 3

The simplest migration model at the micro-level specifies a binary variable (migrate or not) as a function of a set of regressors capturing incentives and constraints to labour mobility. In this approach, migration choice is usually modelled by a logistic regression, either a probit or a logit model. At the macroeconomic level, migration is correctly treated as a resource allocation problem (Sjaastad 1962). People move for work because they calculate that the additional returns to doing so outweigh the additional costs. Households (when these are the decision-making units) accept the loss of a productive worker at home in return for the expectation of a flow of remittances that will more than compensate the loss.

In Vietnam, previous studies indicate that migration is a key response of households and individuals to both economic opportunities and livelihood difficulties. A popular strand of research on the determinants of migration is to use the macro-gravity model. Dang et al. (1997) used 1989 Census data and found, not surprisingly, that more highly developed provinces attracted higher volumes of migrants, other things being equal, while the government’s organised population movements appeared unsuccessful. Phan and Coxhead (2010) used data from the 1989 and 1999 censuses to investigate migration patterns and determinants and the role of migration on cross-province income differentials. They found that provinces with higher per capita income attract more migrants. However, the coefficient of income in the sending province was also positive and significant, implying that the ‘liquidity constraint effect’ outweighed the ‘push’ effect in inhibiting migration in poorer regions.

Nguyen-Hoang and McPeak (2010) used a macro-gravity model to study the determinants of interprovincial migration using annual survey data on population released by the General Statistics Office (GSO) of Vietnam. The authors included urban unemployment rates and policy-relevant variables in their model. They found that migration is influenced primarily by the cost of moving, expected income differentials, disparities in the quality of public services, and demographic differences between source and destination areas.

Several other authors have applied micro-approaches to assess drivers of migration. Nguyen et al. (2008) used panel data of households in 2002 and 2004 to explore factors associated with outmigration both for ‘economic’ and for ‘non-economic’ reasons and comparing short and long-term migration. They applied a probit model and found that migration is strongly affected by household and commune characteristics. Larger households, and households with a high proportion of working members, tend to have more migrants. Higher education attainments of household members also increased the probability of migration. They found evidence of a ‘migration hump’ for long-term economic migration—that is, the probability of migration has an inverse U-shape with respect to per capita expenditures. The presence of nonfarm employment opportunities lowered short-term migration, but not long-term movements. Their core regression analysis, however, did not test for ethnicity-based differences in migration rates.

Tu et al. (2008) examined the impacts of distance, wages and social networks on migrants’ decisions. They modelled the migration decision as a function of choice attributes and individual characteristics. Choice attributes include wages in destination areas, transport between origin and destination, migrants’ social networks, farm prices and local job opportunities. Individual-specific factors include age, education, gender, marital status, and the shares of children and elders in the household. They find that wages and networks have significantly positive effects on migration choices, while distance affects them negatively.

Phan (2012) developed an agricultural household model to determine whether credit constraints are a motivation for or a deterrent to migration. Using survey data from four provinces, she found that for households with high demand for agricultural investments and high net migration returns, migration is used as a way to finance capital investments.

Fukase (2013) investigated the influence of employment opportunities created by foreign-owned firms on internal migration and destination choices. The author used both the Vietnam Migration Survey 2004 and VHLSS2004 and used multinomial logit and conditional logit models. This paper found that the migration response to foreign job opportunities is larger for female workers than male workers; there appears to be intermediate selection in terms of educational attainment; and migrating individuals on average tend to go to destinations with higher foreign employment opportunities, even after controlling for income differentials, land differentials, and distances between sending and receiving areas.

Niimi et al. (2009) look at the determinants of remittances instead of migration. They find that migrants send remittances to their original households as an insurance method to cope with economic uncertainty. Remittances are more likely to be sent by high education migrants in big cities such as Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City.

Recently, Nguyen et al. (2015) used data from several rounds of a three-province survey in central Vietnam and found that households are more likely to move from rural to urban areas when exposed to agricultural and economic shocks. However, the probability of migration decreases with the employment opportunity in the village.

3 Data

3.1 All Migration

This study relies on the VHLSS rounds of 2010 and 2012, conducted by the GSO with technical support from the World Bank in Vietnam. The most widely accessed forms of these surveys contain detailed information on individuals, households and communes, collected from 9402 households nationwide. Individual data include demographics, education, employment, health, and migration. Household data are on durables, assets, production, income and expenditure, and participation in government programs.

The VHLSS2012 contained a special module on migration. Respondents—that is, the heads of interviewed households—were asked about all former members who had departed the household. The module defined former household members as (1) those who had left the household for 10 years or more; and (2) those who had left the household for less than 10 years but were still considered ‘important’ to the household in terms of either filial responsibility or financial contributions.

Certainly, not all those former household members can be considered migrants. Some people leave or separate from their households—for example, due to marriage or separation—and continue to live nearby. Therefore, we define migrants as living in a different province from the household. Interprovincial migration is more costly than intraprovince migration.Footnote 4 We also exclude migrants who left the household more than 10 years prior to the 2012 survey, as the time lapse is too long to be useful. There can be large measurement errors in data on pre-migration variables of migrants, since respondents’ memories grow increasingly faulty. We also exclude migrants reported as having left home when they were younger than 15.

Another set of questions asks about the migration experience of household members. A household member is considered as having migration experience if that person was absent from the household for the purpose of employment for at least 6 months during the past 10 years. This group basically includes two types: (1) migrants who still visit their origin households, and (2) migrants who have left the household permanently. The total number of individual observations is 26,015, of which 1974 are considered migrants. These, however, may have moved away at any time one to 10 years prior to the 2012 survey.

3.2 Recent Migrants

To model recent migration, we take advantage of a panel data link between adjacent rounds of the VHLSS, and we use the so-called large sample VHLSS, which covers an additional 37,000 households to the 9402 in the small sample.Footnote 5 The 2010 and 2012 VHLSSs contain a panel that covers 21,052 households. In this panel data there are 5075 household members who were present in the VHLSS in 2010 but not in 2012. Of these recent migrants, 1150 (22.7%) were reported as having left for employment elsewhere. Information about this group is especially powerful as they comprise a single migrant cohort. Moreover, their decisions are responses to the most recent trends in the Vietnamese economy, as opposed to those of the full sample, who have made their decisions at different points over a decade-long interval. We expect less heterogeneity within the recent migrant group, and also more accurate information about them from respondents. There is also less time in which their characteristics might change (for example, acquire more education)—a problem that may afflict reporting on the longer-term migrants described above.

For consistency with the previous definition, we define migrants as those aged 15–59 who moved across provincial boundaries. In the 2010–12 VHLSS panel, data on whether individuals moved across provinces are collected only for migrants reported as having moved for employment. For individuals who left their households for other reasons, such as marriage or separation, there are no data on the destination. We cannot know whether these individuals moved within or between provinces. Thus, we will focus on recent migration for the purpose of work only. The total number of individuals used for this analysis is 54,898, of which 953 are defined as migrants for employment.

4 Migration Patterns in Vietnam

Figure 1 shows the purposes and the destination of migrants as reported in the migration module of VHLSS2012. More than half of migrants moved for employment purposes. Marriage is the second stated reason, accounting for 21%, followed by study (13%) and all other purposes (11%). In this chapter, we will focus on work migration. However, we also examine patterns and determinants of non-work migration. Although non-work migration may not be determined primarily by economic motives, it is likely to improve the welfare of the migrant-sending household, if only by reducing dependency ratios (Nguyen et al. 2011). Moreover, the female labour force participation rate is very high in Vietnam, where marriage is typically patrilocal. So even though women may report moving for marriage, they are also quite likely to rejoin the labour force in their destination.

Migrant destinations are very highly concentrated. Half of all interprovincial migrants went to the Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) metropolitan areaFootnote 6 and almost one-fifth (19%) to the Hanoi metropolitan areaFootnote 7 (Fig. 2). Of the remainder, 3% moved to one of three other major cities (Hai Phong, Da Nang, and Can Tho) and the rest to other internal destinations or to other countries. With three-quarters of all interprovincial moves going to cities, the ‘rural–urban’ stylisation is a very accurate one for Vietnam. The destination of recent work migration in the panel of VHLSS2010–12 is also similar to the 2012 data.

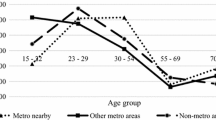

Figure 3 shows the age distributions of migrants. Younger people are far more likely to move than older people; in both surveys, the mode is 20 years. Older workers have diminished incentives to move, in part because a shorter payoff period decreases the net gains to migration (Borjas 2005). All migrants, whether for work or not, are younger on average than non-migrants. Their average age is 23, which is 12 years lower than the average age of non-migrants. Other characteristics of migrants and non-migrants are summarised in Appendix Table 7.

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of migrants. The proportions of work and non-work migrants from VHLSS2012 are 4.3% and 3.3%, respectively. In the 2010–12 panel, 1.7% migrated recently for work. Males have a higher rate of migration for work, but a lower rate for non-work than females. Kinh (ethnic majority) and Hoa (ethnic Chinese) people are more likely to migrate than other ethnic groups. A large proportion of ethnic minorities live in mountainous and remote areas and have limited information on migration opportunities. Migration costs may also be higher due to long distances to cities. But we shall see in the next section that distance and remoteness alone do not account for differences between Kinh/Hoa and ethnic minority groups.

Among those who move for work, Table 1 shows a weak inverse-U–shaped relation between education and migration. People with very low or very high education migrate for work at lower rates than those with middle-level education (i.e. secondary school). This pattern appears both for all migrants and for those moving in the 2010–2012 period, but not among non-work migrants. Since education and household wealth are typically correlated, it presumably reflects the same forces that produce an inverse-U–shaped relation between wealth and migration: migration rates are typically higher for middle-income households than for either the very poor, who may lack the means to move, or the very rich, for whom the gains from migration might be relatively small.

By region, people in the Central Coast are most likely to migrate, followed by those in the Mekong River Delta (Table 2). People in the South-East—the richest region—have the lowest migration rate. Much of the South-East region is already integrated with the greater Ho Chi Minh City metropolitan area. Urban people also move, but the proportion is higher in rural than in urban areas.

Migrants change jobs in ways that reflect the economic structure of destinations. Table 3 shows the occupational transition matrices of migrants, where the occupation skill level is based on VHLSS occupation codes.Footnote 8 Even though these data include non-work migrants as well as those moving within or into the labour market, the trends are clear. In panel (a), the largest off-diagonal transitions are from unskilled jobs or no work (including school) into semi-skilled occupations, which include construction, process and production line work and other categories related to the fast-growing urban-industrial economy. Panel (b) shows that two-thirds of new semi-skilled workers in the migrant sample came from either unskilled jobs (28.8%) or not working (36.9%).

Similarly, two-thirds (65.9%) of new skilled workers were not working prior to migration. These transitions are matched by sectoral changes. In panel (c), only one-fourth (25.6%) of workers in agriculture remain in that sector after migration, whereas 60% transition into industry or services (mainly the former). Former farm workers make up one-third (33.4%) of new industrial sector jobs taken by migrants (panel (d)).

5 Estimating Model

In this section, we explore factors associated with the migration decision. The workhorse model for migration decisions is the logistic regression model. This estimates an individual’s likelihood to migrate as a function of individual characteristics and the characteristics of their household and community. In particular, we have the following form:

where yijk is the migration variable of individual i in household j in commune k. This is a binary outcome, with 1 corresponding to an individual being a current migrant and 0 otherwise. INDIVIDUALijk, HOUSEHOLDjk, and COMMUNEk denote vectors of corresponding characteristics. F is the logistic function, which can be expressed as follows:

where Xβ denotes (α + INDIVIDUALijkγ + HOUSEHOLDjkδ + COMMUNEkθ).

The individual variables in a model of this kind include age, gender, ethnicity, and education. Typical household variables include household composition, characteristics of the household head, and household assets including land and claims on pensions and transfers. The characteristics of origin locations (in Vietnam, communes) include geography, infrastructure and community-level proxies for the existence of migrant networks.

In our study, people are reported as migrating for both work and non-work purposes. It is not clear to us whether this distinction is meaningful, as undoubtedly many of those who migrate for ‘non-work’ purposes ultimately seek and find employment in their new home. However, the fact they reported different reasons for moving may itself convey information about differences among individuals. Therefore, to take this distinction into account, we estimate a multinomial logit (MNL) model. Whereas the logit model allows only for a binary choice (migrate/not migrate), in the MNL model the outcome variable y is not binary, but discrete. Individuals have three mutually exclusive choices: migrate to work, migrate for non-work reasons, and not migrate. In this model, y is equal to 1, 2 or 3 if an individual selects ‘migrate for work’, ‘migrate for non-work’ and ‘not migrate’, respectively. The model is as follows:

in which the third choice, ‘not migrate’, is the reference category. X is a vector of individual, household and commune characteristics, as previously described, and β is a vector of coefficients to be estimated.

The MNL can be easily extended to more than three choices. In a second set of estimates, we also examine propensity to migrate by destination. Individuals face four mutually exclusive choices: migrate to Hanoi or HCMC, migrate to other provinces, migrate abroad, and stay at home.

Since the estimating functions are nonlinear, the partial effects of control variables vary across the X vector. We will report their marginal effects, calculated as estimated partial derivatives with respect to X, evaluated at the mean values of X.

Finally, it is important to note that some explanatory variables could be endogenous with respect to the migration decision. If migration is positively selected on education, for example, some individuals may invest in more education for the purpose of migration. Our estimates will then be inconsistent. Similarly, measures of household wellbeing and assets in 2012 may in part reflect remittance income from prior migrants. Dealing with this risk is a demanding task in cross-sectional data. The joint use of 2010 with 2012 data helps overcome some (though not all) of these risks.

6 Estimation Results

6.1 Work and Non-work Migration

We first use multinomial logit regressions to examine factors associated with the work and non-work migration decisions of all former household members identified in the VHLSS2012 migration module. The sample consists of all non-migrants and migrants aged between 15 and 59. Variables are as summarised above and in Appendix Table 7 (complete variable lists with summary statistics are shown in Appendix Tables 8 and 9). Note that for migrants, “age” refers to their age at the time of migration.

To capture migration networks, we created a commune-level variable as the ratio of out-migrants to the commune population. The rationale is that a person is more likely to migrate if others in her/his commune have gone ahead. She/he can receive information on migration from other migrants. For rural communes, we also included geographic variables (this information is unavailable for urban areas).

Table 4 presents the marginal effects from the migration choice MNL estimation.Footnote 9 Since an individual faces three mutually exclusive choices, the sum of marginal effects is equal to 0. Therefore, we do not report estimates for the non-migration choice. We do, however, report estimates separately for all migrants and for the subsample of those from rural households.

Most coefficient estimates in Table 4 are of expected sign. Men and women are equally likely to migrate for work, but women are more likely to migrate for non-work reasons. The likelihood of migration diminishes with age.Footnote 10 Ethnic minority people are much less likely to migrate than Kinh or Hoa.

Regarding education, we find that relative to the reference category (no schooling) and after controlling for other covariates, people with post-secondary education are more likely to move and those with either primary or secondary education are less likely. These results corroborate the positive selection hypothesis only for post-secondary schooling. Other studies of internal migration by education level in comparable countries are similarly ambiguous (e.g. Deb and Seck 2009).

Household characteristics play an important role in migration decisions. People living in a household with a female head are more likely to migrate. The age of the household head has an inverted-U–shaped relation with the probability of work migration of household members. As the age of the head increases, the probability of household members migrating for work tends to increase. However, after a peak of around 67 years of age, this probability tends to decrease. The relation between the age of the household head and non-work migration also follows an inverted-U–shaped relation, but this age peak is around 14. It means that the probability of non-work migration of household members mainly decreases as the age of the household head increases. The education (in years) of household heads promotes migration for work, but not for non-work purposes.

Household composition also matters for migration decisions. Migrants are more likely to come from larger households, but less likely to move from households with a large proportion of dependent children. The age dependency rate seems to have no influence. Having a migrant already in the household reduces the chance of migration of other household members. This is because the cost of migration is higher for the remaining household members. For example, if a father already migrated, a mother should stay to take care of children and other dependent members.

Wealthier households—those with better housing, nonfarm income and larger farm land area—are less likely to send their members to migrate for work as well as non-work purposes. Farm households (having crop land) tend to send their members for work migration, presumably to diversify income. However, conditional on having some land, households with larger farm areas send out fewer migrants. A larger farm implies higher agricultural labour productivity. As a result, people with larger farms are less likely to migrate.

We have suppressed full coefficient estimates for regions to save space. These show, however, that populations in the Central Coast, the Northern Mountains and the Mekong River Delta are more likely to migrate than those in the Red River Delta or the South-East Region—the two regions closest to Vietnam’s large cities.

For rural areas, we also examine the effect of community on migration via commune variables. Most of these are not significant. Only people living in mountains and villages without daily markets tend to migrate at higher rates.Footnote 11

6.2 Choice of Destination

Table 5 reports estimates of the choice of migrant destination using an MNL model. As noted above, we use four destination choices: Hanoi or Ho Chi Minh City; other provinces; migrating abroad; and the reference category, not migrating. Once again, we do not report reference category results since these are simply the negative of the sum of the other three.

Age, gender and ethnicity have similar effects on migration decisions, whether to Hanoi/HCMC or to other provinces. There are minor differences between these and international migration, and to foreign countries. It should be noted that international migration is mainly in the form of labour exports to countries such as Taiwan and Malaysia (e.g., see Labor Newspaper 2008; Nguyen and Mont 2010). These labourers find mainly semi-skilled occupations—for example, as process workers in factories and farms. Of course, there are other factors that govern international migration decisions. We do not explore these in detail.

Household variables are more important in internal migration decisions. Households with farmland are more likely to have internal migrants. However, conditional on having land, a greater area tends to reduce the probability of migration, as already seen in Table 4. Other measures of household wealth also discourage internal, but not international, migration.

Geographically, those in the landlocked Central Highlands are much less likely to choose international migration. People from urban areas are less likely to migrate internally than those from rural areas. However, there is no difference between urban and rural areas in the probability to move internationally.

6.3 Recent Migrants for Work Purposes

The analysis of the preceding section refers to all migrants who moved in the decade from 2002 to 2012. In this section, we focus only on the extensive margin of recent migrants aged 15–59 for work, using the panel component of the combined 2010 and 2012 VHLSSs. Decisions made by these migrants can be expected to reflect the most recent information available about labour market conditions and opportunities, which evolve along with the Vietnamese economy.

We use logit regression to evaluate work-related migration decisions for the full sample, and for rural residents as a distinct subgroup. In the full sample there are no commune variables, since in the VHLSS these are recorded only for rural areas. Among the commune variables we add a count of the number of years (of the previous three) in which the commune was reported as having experienced drought conditions. Other weather variables (shown in Table 8) were previously included but were dropped for lack of significance. The data differ in one other way: unlike VHLSS2012, the 2010 data indicate whether or not an individual is single (never married). As might be expected, this is a powerful predictor of migration choices.

Table 6 reports marginal effect estimates for these regressions. It also reports MNL estimates of the destination choices of migrants. In the latter regressions, the reference category (not reported) is non-migration.

The estimation results for recent migrants are very similar to those for migrants over the 2002–2012 period. Among the recent migrant group males, Kinh/Hoa and single people are more likely to migrate for work than females, ethnic minorities and those who are married (including separated, divorced, widowed). Residents of urban areas are also less likely to move. The relation between age and migration is an inverse-U. As age increases, the probability of migration increases. However, after the peak age, estimated at around 19, the probability of migration decreases.

In contrast with the previous results, migration among recent movers is consistently and for the most part significantly positively selected on education (the results for migrants whose education ends with middle school (lower secondary) narrowly miss conventional significance levels, with p < 0.136). Positive selection is consistent with findings from many other empirical studies in the developing world. However, recent work on schooling and wage work suggests that in Vietnam, as in other labour-abundant industrialising economies, a job applicant’s formal schooling qualifications may matter less to potential employers than other more directly observable characteristics (Coxhead and Shrestha 2017).

Household conditions matter to recent migration decisions. Migration is more likely from large households, although other demographic characteristics of the household are unimportant. Household wealth (land and housing quality) are associated with lower propensity to migrate as before, but nonfarm and unearned incomes have no effect.

Network effects are clearly seen to be important among recent migrants. Individuals are significantly more likely to move from households with previous migrants and (in rural areas) from communes with great outmigration rates. Other commune characteristics are insignificant, except that migration out of mountainous areas is more likely.Footnote 12

The results from the 2010–12 panel are more consistent with expectations than those from the 2012 sample alone. However, even after controlling for household and commune-level heterogeneity, the association between ethnic minority status and migration for work remains significantly negative. Members of Vietnam’s ethnic minority groups clearly face barriers to mobility that are not accounted for by our explanatory variables. Whether these are supply side (the pull of localised cultural and kinship ties, for example) or demand side (discrimination on the part of potential employers), or a mix of the two, remains to be discovered.

While an exact comparison is infeasible because of variation in data sources and methods, it is nevertheless instructive to compare our results with those from earlier studies. In the 2000s, economic reasons for migration have dominated (this was not the case in the 1990s, when Vietnam was still in the early stages of its transition from a command to a market economy; see Nguyen et al. 2008). The movement of workers to major urban centres has intensified, and urban–rural discrepancies that underlie differences in labour productivity appear not to have narrowed. Importantly, many of the implied policy conclusions from earlier studies remain true a decade or more later, as we discuss in the next section.

7 Conclusions and Policy Discussion

We have investigated factors influencing internal migration decisions by individuals in households surveyed in the VHLSS, a nationally representative household sample. At individual, household, and community levels, the results, for the most part, confirm prior findings with respect to determinants of migration decisions. Compared with results from the VHLSS2012 migration module, which asked about all migrants over a 10-year recall period, our results are stronger and more consistent with priors when we limit ourselves to examining the decisions of migrants who left within a short and recent window, between the 2010 and 2012 VHLSSs.

Households treat migration as part of their investment and diversification strategy. Migration is often associated with better human capital at both individual and household levels, and with better access to migration networks. Age is also very important for both work and non-work migration. Younger people are more likely to migrate. In Vietnam’s largely patrilocal culture, women move at a higher rate than men for non-work reasons, but there is no appreciable gender differentiation in migration for work. Members of ethnic minority groups migrate at far lower rates, other things being equal, than do their Kinh/Hoa counterparts.

Several ‘push’ factors could be considered important, too. Households with fewer assets and smaller agricultural land endowments are more likely to send out migrants. Agricultural land fragmentation is a major problem in rural Vietnam (Pham et al. 2007). Fragmentation is promoted by aspects of Vietnam’s system of land laws, which inhibit land sales or use of land as collateral (Kompas et al. 2012). Our results support the notion that for rural households with very small farms, labour productivity can be significantly improved through outmigration. To some, this finding may suggest that encouraging nonfarm economic activities in rural areas will have significant (negative) impacts on rural–urban migration. However, Vietnam has a long history of programs intended to subsidise rural development and agricultural productivity growth. It may be time to re-evaluate the returns to programs of this kind, which the government itself has acknowledged have had little direct impact (MOLISA 2009). The opportunity cost of spending on rural development is greater investment in well-functioning modern cities; it may well be the case that the marginal social value of spending on improved urban infrastructure, services and amenities exceeds that of continued efforts to persuade rural populations to remain in place.

Our estimates for the most recent migrant cohort confirm that outmigration from rural areas is positively selected on education. Supposing that education is correlated with important capabilities, including entrepreneurial spirit and the potential for innovation, migration may thus reduce the capacity of the sending household or community to produce, be technologically dynamic, and take advantage of entrepreneurial opportunities. This loss of human capital is offset by remittance receipts. If these are used for productive investments, they might generate substitutes for the lost labour and skills (Phan 2012). But increased spending on consumption could exacerbate losses due to outmigration, even as overall household welfare (as conventionally measured) rises.

For poor rural communities, there may well be externalities to outmigration by the best and brightest young people. While remittance receipts could produce increased demand for employment in construction, personal services and the like, there is probably lower potential for dynamic growth of the local economy through entrepreneurship. The biggest losers, at a community level, would be those households who have not sent out migrants (and so receive no direct remittance flows) and remain dependent on employment growth in the rural economy. In Vietnam, ethnic minority groups are notable for far lower migration rates than the majority Kinh or Hoa groups. Minority groups live mainly in geographically remote and economically deprived areas and are therefore far less well prepared on almost all counts to participate in the gains from expansion of Vietnam’s rapidly growing industrial and urban economies. Poverty among ethnic minorities remains stubbornly high and widespread, even as it has diminished at quite an extraordinary rate among the population as a whole (Kozel 2014). However, our statistical findings confirm the persistence of a large and negative ethnic minority bias in migration rates even after controlling for location and other variables commonly associated with ‘geographical poverty traps’. This bias persists in spite of many years of government programs directed at bringing minority groups into the mainstream of economic life. These programs, we conclude, are either succeeding very slowly or not at all.

Finally, a topic for further research concerns continuing barriers to migration due to the ho khau system. In Vietnam, the impacts of the ho khau remain poorly understood. This is in large part because the main sources of data, including the VHLSS, do not collect information on households that are not registered where they actually reside. A very large fraction of recent arrivals to cities are unregistered. In fact, the number of unregistered people in Hanoi and HCMC is even larger than the number who reported living elsewhere 5 years previously. In the 2009 Census, approximately 350,000 people in Hanoi and one million in HCMC reported living in a different province 5 years previously. Government-provided services for health, schooling, and social protection are tied to the registration system, which restricts or privileges access to those permanently registered. Prior research also found that unregistered migrants paid more for water and electricity in urban areas (Dang and Nguyen 2006).

Unregistered migrants are less likely to seek professional care when ill and less likely to have health insurance (Haughton 2010). Likewise, there is evidence that lack of registration prevents many poor children from attending school. Although unregistered individuals are concentrated in working ages, the number of unregistered children is not insignificant. Qualitative studies have found that urban schools, which are often overcrowded, give priority to children of residents. Unregistered children and those with temporary residence are sometimes required to pay higher fees to attend public schools, must pay to attend private schools, or do not attend school at all (Oxfam and ActionAid 2012). Therefore, an important subject for future research is to learn more about the welfare implications of migration among two specific migrant groups: adults or families accompanied by dependent children, and teenaged youth, especially those who truncate their education at home to join the urban industrial labour force.

Notes

- 1.

The Census identifies an individual as a migrant if he/she was at least 5 years of age at the time of the Census and had changed place of residence within the past 5 years.

- 2.

Imported from China, this system was implemented from 1955 in urban areas and nationwide from 1960. Each household is given a registration booklet that records the name, sex, date of birth, marital status, occupation, and relationship to the household head of all household members. In principle, no one can have his or her name listed in more than one household registration booklet. The ho khau is intended to be tied to the place of residence and to provide access to social services such as housing, schooling and health care in that location. As in China, in Vietnam, changing one’s registered location is a difficult and time-consuming process.

- 3.

Of course, any fully articulated model of household decision-making must also come to terms with intra-household bargaining and distribution, whether by assuming it to take a specific structure or by modelling it directly.

- 4.

There are 63 provinces and cities in Vietnam. The average area of a province or city is 5000 sq. km. As a result, workers do not need to migrate if they are working within a province or a city.

- 5.

There are no data on expenditure for the 37,000 ‘large sample’ households, but other information is as collected in the small sample.

- 6.

The Ho Chi Minh metropolitan region includes the provinces of Bình Dương, Bình Phước, Tây Ninh, Long An, Đồng Nai, Bà Rịa-Vũng Tàu, Tiền Giang and Ho Chi Minh City (eight provinces).

- 7.

The Hanoi metropolitan region includes the provinces of Phú Thọ, Vĩnh Phúc, Thái Nguyên, Bắc Giang, Bắc Ninh, Hưng Yên, Hải Dương, Hà Nam, Hòa Bình and Hanoi (10 provinces).

- 8.

Skilled occupations include leaders/managers from sectors and organisations, high-level experts, and average-level experts. Semi-skilled occupations include office staff, service and sales staff, skilled labourers in agriculture, forestry, and fisheries, manual labourers and related occupations, machine assembling and operating workers. Other workers are defined as unskilled.

- 9.

Many studies using MNL models report tests for the independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA). We conducted Hausmann and Small–Hsiao tests, and both rejected the null hypothesis that IIA holds. However, Monte Carlo studies indicate that these tests are biased towards rejection (Cheng and Long 2007). Ex ante, the choices faced in our model seem ‘plausibly … distinct and weighed independently in the eyes of each decision-maker’ (McFadden 1974). Ex post, estimates using logit models applied separately to each choice yield marginal effects that are very similar to those obtained in the MNL model (results available on request).

- 10.

A quadratic term in age was included in earlier versions, but it was insignificant and subsequently dropped.

- 11.

In other runs, we included variables recording frequency of floods, storms and droughts in the commune; however, these were insignificant in the cross-section estimates and were dropped.

- 12.

In other specifications, recent drought (in the past 3 years) was also found to be a significant stimulus to outmigration for work.

References

Ackah, C., & Medvedev, D. (2012). Internal migration in Ghana: Determinants and welfare impacts. International Journal of Social Economics, 39(10), 764–784.

Acosta, P., Calderon, C., Fajnzylber, P., & Lopez, H. (2007). What is the impact of international remittances on poverty and inequality in Latin America? World Development, 36(1), 89–114.

Adams, J. R., & Page, J. (2005). Do international migration and remittances reduce poverty in developing countries? World Development, 33, 1645–1669.

Borjas, G. J. (2005). Labor economics (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw Hill/Irwin.

Cheng, S., & Long, J. S. (2007). Testing for IIA in the multinomial logit model. Sociological Methods & Research, 35(4), 583–600.

Coxhead, I., & Shrestha, R. (2017). Globalization and school–work choices in an emerging economy: Vietnam. Asian Economic Papers, 16(2), 28–45.

Cu, C. L. (2005). Rural to urban migration in Vietnam. In H. H. Thanh & S. Sakata (Eds.), Impact of socio-economic changes on the livelihoods of people living in poverty in Vietnam. Tokyo: Institute of Developing Economies, Japan External Trade Organization.

Dahl, M. S., & Sorenson, O. (2010). The social attachment to place. Social Forces, 89(2), 633–658.

Dang, N. A. (1999). Market reforms and internal labor migration in Vietnam. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 8(3), 381–409.

Dang, N. A. (2001a). Migration in Vietnam: Theoretical approaches and evidence from a survey. Hanoi: Transport Communication Publishing House.

Dang, N. A. (2001b). Rural labor out-migration in Vietnam: A multi-level analysis. In Migration in Vietnam: Theoretical approaches and evidence from a survey. Hanoi: Transport Communication Publishing House.

Dang, N. A., & Nguyen, T. L. (2006). Vietnam migration survey 2004 internal migration and related life course events. Mimeo. Hanoi: VASS.

Dang, A., Goldstein, S., & McNally, J. W. (1997). Internal migration and development in Vietnam. International Migration Review, 31(2), 312–337.

Dang, N. A., Tackle, C., & Hoang, X. T. (2003). Migration in Vietnam: A review of information on current trends and patterns, and their policy implications. Paper presented at the Regional Conference on Migration, Development and Pro-Poor Policy Choices in Asia, 22–24 June 2003, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Davies, P. S., Greenwood, M. J., & Li, H. (2001). A conditional logit approach to US state-to-state migration. Journal of Regional Science, 41, 337–360.

Deb, P., & Seck, P. (2009). Internal migration, selection bias and human development: Evidence from Indonesia and Mexico. MPRA Paper No. 19214. http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/19214/

Djamba, Y., Goldstein, S., & Goldstein, A. (1999). Permanent and temporary migration in Vietnam during a period of economic change. Asia-Pacific Migration Journal, 14(3), 25–28.

Etzo, I. (2010). Determinants of inter-regional migration flows in Italy: A panel data analysis. MPRA Paper No. 26245.

Feng, S., Oppenheimer, M., & Schlenker, W. (2012). Climate change, crop yields and internal migration in the United States. NBER Working Paper No. 17734.

Fukase, E. (2013). Foreign job opportunities and internal migration in Vietnam. Policy Research Working Paper Series No. 6420, The World Bank.

General Statistics Office (GSO), & United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). (2005). Vietnam migration survey 2004: Major findings. Hanoi: Statistical Publishing House.

Guest, P. (1998). The dynamics of internal migration in Vietnam. UNDP Discussion Paper 1, Hanoi.

Harris, J. R., & Todaro, M. P. (1970). Migration, unemployment and development: A two-sector analysis. American Economic Review, 60(1), 126–142.

Haughton, J. (2010). Urban poverty assessment in Ha Noi and Ho Chi Minh City. Hanoi: United Nations Development Program. http://dl.is.vnu.edu.vn/handle/123456789/94

Huynh, T. H., & Walter, N. (2012). Push and pull forces and migration in Vietnam. MPRA Paper 39559, University Library of Munich, Germany.

Kim, K., & Cohen, J. E. (2010). Determinants of international migration flows to and from industrialized countries: A panel data approach beyond gravity. International Migration Review, 44(4), 899–932.

Kompas, T., Che, T. N., Nguyen, H. Q., & Nguyen, H. T. M. (2012). Productivity, net returns and efficiency: Land and market reform in Vietnamese rice production. Land Economics, 88(3), 478–495.

Kozel, V. (Ed.). (2014). Well begun but not yet done: Progress and emerging challenges for poverty reduction in Vietnam. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

Labor Newspaper. (2008). Exporting labor. Labor Union of Ho Chi Minh City, 11 November 2008 (in Vietnamese).

Marx, V., & Fleischer, K. (2010). Internal migration: Opportunities and challenges for socio-economic development in Vietnam. Hanoi: UNDP.

Mayda, A. (2007). International migration: A panel data analysis of the determinants of bilateral flows. CReAM Discussion Paper No. 07/07. London: Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration, Department of Economics, University College London.

McCaig, B., & Pavcnik, N. (2013). Moving out of agriculture: Structural change in Vietnam. NBER Working Paper No. 19616.

McFadden, D. (1974). Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In P. Zarembka (Ed.), Frontiers of econometrics. New York: Academic Press.

McKenzie, D., & Sasin, M. J. (2007). Migration, remittances, poverty, and human capital: Conceptual and empirical challenges. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4272. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs (MOLISA). (2009). Dê án he thông an sinh xã hoi v_i dân c nông thôn giai đoan 2011–2020. Draft report. Hanoi: Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs.

Molloy, R., Smith, C. L., & Wozniak, A. (2011). Internal migration in the United States. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(3), 173–196.

Nguyen, H. L., & Mont, D. (2010). Vietnam’s regulatory, institutional and governance structure for cross-border labor migration. Working Paper.

Nguyen, T. P., Tran, N. T. M. T., Nguyen, T. N., & Oostendorp, R. (2008). Determinants and impacts of migration in Vietnam. Depocen Working Paper Series No. 2008/01, Hanoi.

Nguyen, V. C., Van den Berg, M., & Lensink, R. (2011). The impact of work and non-work migration on household welfare, poverty and inequality. The Economics of Transition, 19(4), 771–799.

Nguyen, L., Raabe, K., & Grote, U. (2015). Rural–Urban migration, household vulnerability, and welfare in Vietnam. World Development, 71, 79–93.

Nguyen-Hoang, P., & McPeak, J. G. (2010). Leaving or staying: Inter-provincial migration in Vietnam. Asia and Pacific Migration Journal, 19(4), 473–500.

Niimi, Y., Pham, T., & Rilly, B. (2009). Determinants of remittances: Recent evidence using data on internal migrants in Vietnam. Asian Economic Journal, 23(1), 19–39.

Oxfam and ActionAid. (2012). Participatory monitoring of urban poverty in Viet Nam: Five-year synthesis report (2008–2012). Hanoi: Oxfam and ActionAid.

Pham, H. V., MacAulay, G., & Marsh, S. (2007). The economics of land fragmentation in the north of Vietnam. Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 51(2), 195–211.

Phan, D. (2012). Migration and credit constraints: Theory and evidence from Vietnam. Review of Development Economics, 16(1), 31–44.

Phan, D., & Coxhead, I. (2010). Interprovincial migration and inequality during Vietnam’s transition. Journal of Development Economics, 91(1), 100–112.

Sjaastad, L. A. (1962). The costs and returns of human migration. Journal of Political Economy, 70(5), 80–93.

Stark, O. (1991). The migration of labour. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Stark, O., & Bloom, D. (1985). The new economics of labor migration. American Economic Review, 75, 173–178.

Stark, O., & Taylor, J. (1991). Migration incentives, migration types: The role of relative deprivation. The Economic Journal, 101, 1163–1178.

Tu, T. A., Thang, D. N., & Trung, H. X. (2008). Migration to competing destinations and off-farm employment in rural Vietnam: A conditional logit analysis. Working Paper 22. Vietnam: Development and Policies Research Center (DEPOCEN).

Valencia, J. (2008). Migration and its determinants: A study of two communities in Colombia. Atlantic Economic Journal, 36(2), 247–260.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank John Giles and Hai-Anh Dang (World Bank), and Amy Liu and Xin Meng (Australian National University) for helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper. We are also grateful to participants in a seminar in the IPAG Business School, Paris, France, and participants in the conference ‘Study of Rural–Urban Migration in Vietnam with Insights from China and Indonesia’ (Hanoi, Vietnam, January 2015) for helpful comments on earlier drafts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Coxhead, I., Nguyen, V.C., Vu, H.L. (2019). Internal Migration in Vietnam, 2002–2012. In: Liu, A., Meng, X. (eds) Rural-Urban Migration in Vietnam. Population Economics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94574-3_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94574-3_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-94573-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-94574-3

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)