Abstract

In this chapter, I will consider the role of brief interventions in Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy. With its initial emphasis on problem assessment rather than on case formulation, REBT lends itself quite well to brief work. In this chapter by ‘brief’, I mean between 1 and 11 sessions and I will focus on REBT that is brief by design rather than by default. Although often when clients end therapy quickly, and the end is not planned, it should not be necessarily assumed that they have terminated the process ‘prematurely’ as their decision is often ‘mature’ and they are pleased with what they have achieved (Talmon, 1990). In this chapter, I focus on three different formats when discussing brief interventions in REBT (see below).

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

In this chapter, I will consider the role of brief interventions in Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy. With its initial emphasis on problem assessment rather than on case formulation, REBT lends itself quite well to brief work. In this chapter by ‘brief’, I mean between 1 and 11 sessions and I will focus on REBT that is brief by design rather than by default. Although often when clients end therapy quickly, and the end is not planned, it should not be necessarily assumed that they have terminated the process ‘prematurely’ as their decision is often ‘mature’ and they are pleased with what they have achieved (Talmon, 1990). In this chapter, I focus on three different formats when discussing brief interventions in REBT (see below).

What Are Brief Interventions in REBT?

While at first glance, the term ‘brief’ when describing therapy, in general and REBT, in particular, is straightforward, i.e. it refers to therapeutic help that does not last a long time, the reality is far more complex. For example, REBT is described on the Albert Ellis Institute website as ‘short-term therapy, long-term results’. If we take such an approach then it is meaningless to consider brief interventions in REBT as a special topic because, by definition, REBT is intrinsically brief. However, as any REBT practitioner will tell you for a number of clients, therapy involves long-term work. This may be due to the fact that the client has several problems that are difficult to deal and, additionally, they may encounter several obstacles when dealing with these problems. Alternatively, a client may seek longer-term REBT because they first want to address their emotional problems and then want to work towards greater self-development which Mahrer (1967) argued, a number of years ago, were the two major goals of psychotherapy.

There is also the issue of time versus number of sessions. Thus, if a client has a small number of sessions (e.g. 5), but these are spread over a long period of time, (e.g. a year) then should we refer to this as ‘brief’ therapy? Alternatively, if a person has a large number of sessions (e.g. 30) over a short period of time (e.g. 6 weeks) would this be considered ‘brief’? Intensive, surely, but ‘brief’?

As you can see there is no consensus in the field concerning what constitutes ‘brief’ therapy and thus, in this chapter, I will make it quite clear that I will be taking a ‘session number’ focus, not a ‘time’ focus. Thus, for me, brief therapy is 11 sessions or less and I will discuss an 11-session protocol for brief REBT that I have published (Dryden, 1995). I refer to this approach as ‘brief REBT’ as it contains, as will be seen, the major components of REBT, albeit in truncated form. I contrast this with the other two formats which I will refer to as ‘single session therapy using REBT principles and practice’ (Dryden, 2017) and ‘very brief therapeutic conversations using REBT principles and practice’ (Huber & Backlund, 1991). Such conversations, for example, occur at the Albert Ellis Institute’s ‘Friday Night Live’Footnote 1 evenings where two volunteers discuss their problems of living with an REB therapist in front of an audience (Ellis & Joffe, 2002).

Brief REBT: An 11 Session Protocol

I developed a protocol for brief REBT that lasts 11 sessions. I selected this number of sessions after trialing ten, eleven and twelve sessions and found that eleven sessions gave me and other REB therapists sufficient time to cover what needed to be covered.

Suitability Criteria

The following are good indicators for brief REBT:

-

1.

The person is able and willing to present their problems in specific form and set goals that are concrete and achievable

-

2.

The person’s problems can be addressed within brief REBT. In my experience, these problems tend to be:

-

Acute rather than chronic

-

Disruptive to the person’s life in one or two particular life areas but not to the person’s entire life

-

Distressing to the person, but the person’s distress lies within a mild to moderate range of distress. If the person’s level of distress is severe the problem may still be amenable to brief REBT as long as the other criteria listed here are met.

-

In addition, the person is not defensive with respect to the problem(s) and is open to address and change the problem(s)

-

-

3.

The person is able and willing to target, at the most, two problems that they particularly want to work on during therapy.

-

4.

The person has understood the ‘Situational ABCDEFG’ framework used in REBT (Dryden, 2018) - or salient parts of that framework- and has indicated that this way of conceptualising and dealing with their problems makes sense and is potentially helpful to them.

-

5.

The person has understood the therapist’s tasks and their own tasks in brief REBT, has indicated that these seem potentially useful to them and is willing to carry out their tasks.

-

6.

The person’s level of functioning in their everyday life is sufficiently high to enable them to carry out their tasks both inside and outside therapy sessions.

-

7.

There is evidence that a good working bond can be quickly developed between the therapist and the person seeking help.

Getting Brief REBT Off on the Right Foot

It is very important that the brief REB therapist gets therapy off to a good start and they do this by completing the following tasks. The therapist:

-

1.

Begins by suggesting an agenda for the session. This should outline the following items and incorporate what the person wants to put on the agenda.

-

2.

Encourages the person to talk about their problem(s) in their own way, but briefly. In doing so, the therapist shows the person empathic understanding of their problem(s). but does so without reinforcing the client’s idea that ‘A’ causes ‘C’.

-

3.

Helps the person to specify their problems and suggests that they work with two of these problems for brief REBT, if they specify more than two. If two are selected, the therapist asks the person to nominate one of these problems that they would like to focus on first. This becomes the person’s ‘target’ problem.

-

4.

Helps the person to set a goal in line with the target problem as it has been specified. As the person does so, the therapist ensures that this goal are within the person’s control, stated positively, observable (or have a referent that is observable), achievable and health promoting.Footnote 2

-

5.

Teaches the person the ‘Situational ABCDEFG’ model of REBT (Dryden, 2018) either using one of the person’s problems as content or a generalised problem example.

-

6.

Explains their tasks as a brief REB therapist and suggests what the person’s tasks would be if they become a client in brief REBT.

-

7.

Decides with the person whether or not they are a good candidate for brief REBT. If so, the two contract for brief REBT and the person becomes a ‘brief REBT’ client. If not, the two may contract for longer term REBT or the therapist may refer the person to a practitioner of a therapeutic approach better suited to what the person is looking for.

-

8.

Negotiate the first homework assignment with the client with the target problem in mind.

Assessment and Goal Setting

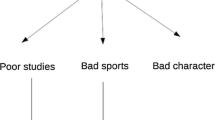

The next task that the therapist has in brief REBT is to help themself and the client understand the target problem using the ‘Situational ABC’ part of the ‘Situational ABCDEFG’ framework used in REBT. At the same time, the therapist also helps the client to learn how to assess their problems themself, if they are interested in doing so. In doing this, they may use one of a number of REBT self-help forms that are freely available in the professional domain (e.g. Dryden & David, 2009). As is typical in REBT, the therapist encourages the client to select a specific example of the target problem to facilitate assessment. Assessment involves the therapist first identifying the client’s unhealthy negative response, unconstructive behavioural response and highly and negatively distorted thinking response (at ‘C’) to the adversity (at ‘A’). Then and most importantly, the therapist helps the client to identify the irrational beliefs that they hold (at ‘B’) about the adversity that accounts for these problematic responses. Once the client has seen this, they can be said to understand the ‘irrational belief-disturbed C’ connection.

An important part of assessment is to determine whether the client has a meta-emotional problem (an emotional problem about their target problem). If so, the therapist and client need to deal with this first, if the client agrees and if its presence interferes (a) with the two of them working on the target problem in the therapy room and (b) with the client working on the target problem outside the therapy room.

Once assessment has been completed the therapist helps the client to set a goal in line with the problem as assessed (‘G’ in the ‘Situational ABCDEFG’ framework). What is important here is that the client’s goal represents a healthy response to the adversity identified at assessment. In particular, the client is helped to nominate a healthy negative emotional response, a constructive behavioural response and a realistic and balanced cognitive response to the adversity and to identify the rational beliefs that they would need to hold about the adversity that would enable them to experience these healthy responses. Once they have seen this they can be said to understand the ‘rational belief-healthy C’ connection.

Disputing and Understanding

Once the client’s target problem has been assessed and they have understood the role that their irrational and rational alternative beliefs play in their problem and in achieving their goal, the therapist can help them to stand back and dispute these beliefs (at ‘D’) and to commit themself to developing their rational beliefs. Disputing involves the therapist encouraging the client to examine their irrational and rational beliefs from an empirical standpoint, a logical standpoint and a pragmatic standpoint. The goal of disputing is to help the client understand (at ‘E’) that their irrational beliefs are false, illogical and lead to predominantly unhealthy results and that their alternative rational beliefs are true, logical and lead to predominantly healthy results. Where appropriate, the client is also taught how to question their irrational and rational beliefs for themself and the therapist suggests appropriate self-help material to facilitate the client doing this (Dryden, 2001).

The client is helped to see that this understanding is likely to be ‘intellectual’ rather than ‘emotional’ in nature. Ellis (1963) distinguished between intellectual insight and emotional insight. He argued that intellectual insight involves a cognitive understanding of why an irrational belief is irrational and why the alternative rational belief is rational without this impacting on the person’s feelings and behaviour. By contrast, he argued that emotional insight involves a deeper felt conviction into the same point which does impact on the person’s feelings and behaviour. While a minority of clients do experience an immediate change in feelings, behavior and related thinking once they have recognised and changed their irrational belief to a rational belief for such change to last, all clients need to internalise their rational beliefs which is the subject of the next section.

Engaging Emotions in the Disputing Process

As I will discuss below, perhaps the best way of promoting belief change outside the session is for the client to act repeatedly in ways that support their developing rational beliefs while facing the adversity at ‘A’. However, the best way of promoting such change inside the session is for the client to be helped to argue in favour of these beliefs in a forceful manner while their healthy emotions are engaged. This is particularly important in brief therapy where time is at a premium. REBT has a number of techniques that can be grouped under this heading. The following techniques are a few examples of those that can be used in brief therapy to encourage belief cahnge in this respect.

Rational-emotive imagery

Here, the client is asked to imagine disturbing themself in response to the adversity at ‘A’ and then to develop a healthy emotional response to the same ‘A’ with the therapist ensuring that this was achieved by a belief change from irrational to rational.

Forceful recorded disputing

Here the client is encouraged to record themself disputing beliefs and to ensure that the rational part of themself is more forceful and more persuasive than the irrational part.

Chairwork (Kellogg, 2015)

The use of chairs in REBT where the client can play both their rational belief and their irrational belief having a dialogue is a particularly vivid and emotional way of engaging the client in the belief change process. The therapist searches for ways of encouraging the client in the rational belief chair to respond persuasively to their irrational belief in the other chair. This method is also useful in helping both therapist and client to discover irrational arguments to which the client struggles to respond. This can then be discussed outside of chairwork before it is resumed once the client has developed a persuasive argument to their irrational voice. A variety of emotive techniques can be negotiated for use as homework assignments to ensure that the client retains their focus on belief change between sessions.

Repeated Integrated Action and Thinking to Promote Change

In REBT, in general, it is thought that the best way for the client to facilitate change (at ‘F’) is for them to (i) face adversity while rehearsing their developing rational beliefs and (ii) act and think in ways that are consistent with these beliefs and that will support their development and (iii) do such practice repeatedly. I refer to this practice as ‘integrated action and thinking’ because it brings together, in integrated form, rational beliefs, constructive behavior and realistic thinking. In brief REBT, in particular, the client is called upon to do more of this practice to benefit from its limited number of sessions than in ongoing REBT. Consequently, it is important that the client commits sufficient time to do this practice. Negotiating and reviewing homework tasks are key for both therapist and client here. Emotional change is deemed to occur as a result of this repeated, integrated action and thinking.

While change is best promoted between sessions, brief REB therapist often use techniques within sessions which also aid this change process and which can be taught to the client for their later use (Dryden, 1995). Common techniques which are designed to do this include those which (i) encourage the client to develop and use persuasive arguments in support of their rational beliefs; (ii) promote a variety of rational and irrational dialogues where the client accesses both rational and irrational beliefs and engages in a debate designed to help them to develop conviction in the former and to let go of the latter; (iii) enable the person to use imagery to rehearse the integration of rational beliefs with constructive action and realistic thinking while imagining facing adversity. This is often done before the client faces adversity in reality.

Dealing with Obstacles to Change

Obstacles to change probably occur in all types of psychotherapy and REBT is no exception. In brief REBT, the more such obstacles can be anticipated and dealt with in advance the better. However, if such obstacles are encountered in reality, these often take the form of (a) adversities unrelated to the target problem or (b) discomfort-related adversities. The therapist and client use the ‘Situational ABCDEFG’ framework with the therapist encouraging the client to take the lead to deal effectively with these adversities. Obstacles to change may also take the form of one or more doubts, reservations and objections (DROs) to some aspect of brief REBT. Here, the therapist helps the client to identify the misconception that usually is at the heart of the DRO and to correct it.

Most of the time, the therapist can help the client deal with such obstacles within the paradigm of brief REBT. When this is not the case then the therapeutic contract needs to be renegotiated.

Generalization and Ending

When the client has achieved their goal with respect to their first target problem, then the therapist encourages them to generalize their learning to deal with their second target problem (when they have selected such a problem). Here, the client is invited to take the lead and use the REBT emotional problem-solving process that they learned in dealing with their first target problem with the therapist prompting the client when needed. In addition, the therapist encourages the client to generate rational beliefs and to use specific variants of these general beliefs in other problem areas beyond the two problems targeted for change in brief REBT.

It is at the generalization stage that therapist and client are likely to agree to increase the interval between therapy sessions and while brief REBT formally ends at the 11th session, a follow-up session can be carried-out at a suitable future date to enable both to evaluate the client’s progress.

Single Session Therapy Using REBT Principles and Practice

Single session therapy (SST) has been defined as “one face-to-face meeting between therapist and a patient with no previous or subsequent sessions within one year” (Talmon, 1990: xv). In my view, the main feature of REBT-inspired SST is to offer the client one thing that the person can take away from the experience that would make a difference to their problem and which they can maintain after SST has been concluded. This, ideally, should be a rational belief with which the client resonates and which the person can implement in a relevant part of their life (Keller & Papasan, 2012).

In the REBT-inspired approach to SST that I have developed (Dryden, 2017) there are four points of contact: (i) When the person contacts the therapist for the very first time; (ii) the pre-session telephone contact; (iii) the face-to-face session; (iv) the follow-up telephone session after 3 months. As you can see, as only one of these four points of contact takes place face-to-face within the 1 year period stipulated by Talmon, my approach is an example of single session therapy. Before I discuss each point of contact in more depth, let me say a little about the indications and contra-indications of REBT-inspired SST.

Indications and Contra-Indications for REBT-Inspired SST

I will first outline some of the indications for this approach to SST.

Indications

In my experience, the following are indications for REBT-inspired SST;

-

A person who experiences an everyday, non-clinical emotional problem of living (anxiety, non-clinical depression, guilt, shame, anger, hurt, jealousy and envy)

-

A person who has a relationship issue at home and at work or who is seeking advice and help with dealing with others

-

A person who experiences an everyday problem of self-discipline

-

A client who is in ongoing therapy but who wants brief help with a problem with which their therapist can’t or won’t help them. It is important that the other therapist agrees to you seeing them for SST

-

A therapy trainee who wants to find out what it is like to have therapy from a different perspective

-

A person who is ready to ‘take care of business now’ and whose problem is ‘non-clinical’, but amenable to a single session approach. This problem may become ‘clinical’ if not dealt with

-

A person who is ready to take care of business now and whose problem is ‘clinical’, but amenable to a single session approach (e.g. simple phobias – Davis, Ollendick, & Öst, 2012 and panic disorder – Reinecke, Waldenmaier, Cooper, & Harmer, 2013).

-

A person who is stuck and needs some help to get unstuck and move on

-

A person who views therapy as providing intermittent help across the life cycle

-

A person who has a self-development or coaching goal

-

A person with a clinical problem, but who is ready to tackle a ‘non-clinical’ problem

-

A person who is open to therapy, but wants to try it first before committing themself

-

A person who wants some prophylactic assistance

-

A person who has a meta-emotional problem

-

A person who requires prompt and focused crisis management

-

A person who has a life dilemma

-

A person who is required to make an important, imminent decision

-

A person who is finding it difficult to adjust to life in some way

-

A person who is seeking advice on how REBT would tackle their problem

Contra-indications

The following are some contra-indications for REBT-inspired SST

-

A person who does not want REBT or CBT of any description

-

A person who requests ongoing therapy

-

A person who needs ongoing therapy

-

A client who has many vague complaints and can’t be specific

-

A client who is likely to feel abandoned by the therapist at the end of the process

The Process of REBT-Inspired SST

As I mentioned above there are four points of contact in REBT-inspired SST. In outlining these I will refer to my own experience as a single session therapist using REBT principles and practice (Dryden, 2017).

Point of contact 1: The very first contact. When a person first contacts an REB therapist they are either making an enquiry about the therapist’s services or applying for that person’s help. At that contact, I outline my services including single session therapy. If they show an interest in SST, I then have a brief conversation with them to determine whether they are suitable for and may benefit from SST and agree with its practicalities (format, timing and fees). If the signs are promising, then I schedule a 30-min telephone schedule to confirm the person’s suitability for SST and to help them get the most out of the process. This telephone call should be arranged as soon as possible to create a momentum.

Point of contact 2: The pre-session telephone contact. The tasks of the SS therapist in this contact are to:

Confirm that the person is suitable for SST. If the person is suitable then they have a clear and realistic idea what they want to gain from the process and are ready to take immediate steps to achieve their goal.

Elicit the client’s view of the therapist’s role in helping them to achieve their goal.

Here, the client often says that the therapist’s role is to “help me to put things into a different perspective” or “help me to approach the problem differently”. The therapist uses such statements to show that they are consistent with REBT-inspired SST.

Ask the client to outline what they already have they done to address the problem. In doing so, the therapist discovers what has been helpful and unhelpful about doing so. The therapist aims to build on the latter and distance their approach from the latter.

Discover the client’s strengths and resources. The purpose of SST is to build on the client’s pre-existing strengths and help them draw upon extant resources rather than to start from scratch in each area. One discovered, the therapist’s role is to remind the client to use these strengths and resources in the face-to-face session.

Encourage the client to do any relevant homework task before the face-to-face session. Depending upon what emerges in the pre-session telephone contact, the therapist will want to suggest something that the client can do before the face-to-face session to initiate the process. Once again this session should be arranged as soon as possible after the phone call.

Point of contact 3: The face-to-face session. The face-to-face session usually lasts for approximately 50 min (unless there is good reason to extend it as in a single extended session when working with simple phobias, Davis et al., 2012).

Build a bridge between the phone-call and the session. The first thing that the therapist should do is to pick up on any preparatory work that the client has done between the end of the phone contact and this session. In addition, the therapist should enquire about any changes that the client may have noticed since they had the phone call and build on any such changes.

Create a focus. The therapist’s next task is to help the client to create a focus for the session and then to identify the person’s target problem (i.e. the problem they want to be helped with) and the goal with respect to that problem. Problem and goal assessment follow, based on a selected example of the problem. There is some value in the client selecting an anticipated example of the problem to help the person apply their learning in the session to that situation.

Identify the central mechanism. By the central mechanism I mean the major irrational belief (s) and associated behavior and thinking that are responsible for the existence and maintenance of the problem.

Dispute the irrational belief(s). The next stage is for the therapist to help the client to examine at least the one major irrational belief that is deemed largely responsible for the problem and to modify this and plan on acting on the new rational belief. Throughout this process the therapist looks for ways to help the client to generalize learning.

Rehearse the rational belief in the session. It is very useful if the therapist can find a way to make an emotional impact on the client which may encourage learning and later application. This is best done when the therapist gives the client an opportunity to rehearse their new belief in the session. Some variant of two chair work (see Kellogg, 2015) or rational-emotive imagery (Dryden, 2001) are often useful in this context.

Implementation. After such rehearsal, the therapist should initiate discussion concerning how the client is going to implement their learning in their everyday life as soon as possible after the session. Any potential obstacle should be identified and addressed. At the end of the session a final summary should be made preferably by the client and augmented by the therapist and any loose ends tied up. A definite appointment should be made for the follow-up session 2–3 months in the future.

One of the features of my approach to REBT-inspired SST (Dryden, 2017) is that I record the session and offer my client the digital voice recording (DVR) of the session and/or a typed transcript of the session. I find that doing so aids client reflection and gives the client something to review after the final session and provides a useful bridge between the face-to-face session and the follow-up session.

Point of contact 4: The follow-up session. Some clients say that knowing that they were going to have further contact with the therapist is a motivation to help them maintain the gains that they made from the session. Others welcome the chance to reflect on the process and it also serves as a reminder of what was achieved since the face-to face session and what can yet be achieved.

Follow-up also enables the therapist to discover what was helpful and not so helpful about their contribution to the process and thus, it aids their development as an REBT-inspired SS therapist. Finally, if the therapist works in a service that collects data on intervention effectiveness, follow-up is crucial in finding out just how effective REBT-inspired SST is with certain groups and populations. It also yields data on differential effectiveness among therapists.

Very Brief Therapeutic Conversations (VBTCs) Using REBT Principles and Practice

The final brief intervention in REBT that I will discuss in this chapter is what I refer to as ‘very brief therapeutic conversations using REBT principles and practice’. This form of brief intervention was developed initially by Albert Ellis in his ‘Friday Night Workshops’ in 1965. At these workshops, Ellis publicly interviewed two volunteers from the audience on so-called ‘problems of living’ which were normally emotional and/or behavioral in nature, These sessions lasted for about 30 min and were followed by a question and answer session involving audience members. Research has shown that such short interviews are frequently rated as ‘helpful’ or ‘very helpful’ by the volunteers themselves and seem also to benefit audience members (Ellis & Joffe, 2002). After Ellis’s death in 2007, the Albert Ellis Institute has continued this tradition of ‘very brief therapeutic conversations’ at its ‘Friday Night Live’ event. In Britain, I have done over 300 of such public demonstration sessions of REBT which are generally 20–30 min in length and sometimes considerably less (see the session transcript below). Before the sessions, I usually give a lecture on a particular theme (e.g. shame) and invite volunteers who wish to be helped with their particular problem of the evening’s focused theme. The purpose of these demonstrations are twofold. First, they have a therapeutic purpose: to provide the volunteers with some help for their problems. Second, they have an educational purpose: to give people an idea of REBT in action.

When calling for volunteers, it is important that the therapist asks that the person volunteering brings a genuine, current problem or issue for which they are sincerely seeking help. Role-played problems are neither helpful to the person playing the role, to the therapist providing the ‘help’ and showing how REBT works, nor to the watching audience who may want to learn more about the practice of REBT or may want to apply what they see to their own, similar problems.

One of the features of VBTCs that take place in a public setting is that the therapist knows nothing about the clientFootnote 3 or about the issue they are going to raise. Consequently, there are no indications or contra-indications for this type of help other than the aforementioned point about the importance of the client seeking help for a genuine problem or issue.

Let me outline some of the features of ‘VBTCs using REBT principles and practice’ as I see them. These principles apply mainly where the conversation takes place in a public setting, but also apply whn it is taking place in private.

‘Primum non nocere’

The principle of ‘first, do no harm’ is enshrined in the helping professions, but is particularly important in public VBTCs where the therapist knows nothing about the person that they are meeting for the first time, but knows that the time that they have together is very limited. While the therapist may wish to show REBT in action to those present, their first duty is the client’s welfare and when the two clash, the latter is prioritized. Having said that, in the 300 public VBTCs that I have conducted, I have never felt that the client’s well-being was being compromised. Even when the client felt and displayed distress, they never opted to stop the interview when asked if they wanted to do so. Nevertheless, the therapist does need to be prepared to offer extra help if needed and I am happy to do so directly after the event finishes or soon after,

Therapeutic Style

In public VBTCs, the most effective REB therapists display a therapeutic style comprising the following three elements.

Creating and maintaining a focus

REBT is a form of active-directive therapy (Ellis, 1994). This is certainly true of REBT-inspired VBTCs. Perhaps what is even more important is the ability of the therapist to create and maintain a focus throughout the conversation.

Demonstrating empathy

It is important that the client experiences the therapist as empathic, but it is also important that the therapist does not reinforce a causal ‘A-C’ connection while doing so even if the client makes this connection themself.

Using appropriate humor

I pointed out above that VBTCs have therapeutic and educational value. While the entertainment value of VBTCs should always be secondary to its other values, it should be noted that humor, which is an important feature of VBTCs, is both entertaining, therapeutic and educational. Indeed, therapist humor often helps the client to keep an open mind about the therapist’s message, particularly where this may be otherwise unpalatable. Ellis (1977) has written on the role of humor in REBT, but cautioned against the use of humor that can be construed as ‘ad hominem’ (directed at the person) rather than ‘ad opinionem’ (directed at the person’s belief).

Just One Thing

The therapist’s goal in a VBTC is to provide the client with one meaningful point that they can take away with them that will make a difference to the way they deal with their problem or issue (Keller & Papasan, 2012). While the REB therapist may hope that this point may refer to the therapeutic value of a rational belief, this may not necessarily be the case (unlike in REBT-inspired SST where it is more likely to be the case). The important factor is that this one thing is meaningful to the client and can potentially lead to some kind of therapeutic change.

One Problem/Issue

Due to the very limited time available in the VBTC, it is important that the therapist ensures that they work with only one client problem or issue. When the client brings up more than one at the outset, then the therapist urges them to select the one problem which they would like to focus on. This may be the problem that the person thinks can be most easily solved or it may be one about which they are most troubled. The most important point here is that once a particular problem has been selected then both therapist and client keep to this problem unless there is a good reason not to do so.

One Example

While therapist and client can deal with a problem or issue in general terms, it is preferable for them to work with a specific example of the problem or issue as selected by the client, if this is at all possible. Indeed, I usually suggest to the client that they choose a specific example of their problem/issue that is imminent. I do so to facilitate them putting into practice whenever they learn from the VBTC. This is a more direct way of proceeding than using a past example of their target problem, working that through and then applying learning to a nominated future example. A specific example of the target problem should be located in a specific setting, with specific people present and occurring a specific time. A specific example may be actual or imaginal.

Accurate Assessment Is Important and Worth Spending Time Over

In my experience conducting VBTCs, it is important to devote sufficient time to assessing accurately the specific example of the client’s target problem using the ABC assessment framework of REBT. In particular, pinpointing the ‘A’, with accuracy, is perhaps the most important part of the assessment. In addition, when identifying the client’s irrational beliefs, it is useful to help them to identify their rational alternative beliefs at the same time. Helping the client to understand the ‘irrational belief-disturbed C’ connection and the related ‘rational belief-healthy C connection’ both within the context of the adversity at ‘A’ is particularly important.

Goal Setting

Helping the client to select a goal can be done at any point in the VBTC process, but in my view, it is best done just after the assessment and where the client indicates that they understand the relationship between their beliefs and their responses to the adversity, both disturbed and healthy. Such understanding encourages the client to set a healthy response to the adversity at ‘A’ before the work proceeds.

Disputing and Choice

The reason that I recommend that the therapist helps the client to identify both irrational and rational beliefs at the same time during the assessment process, is to help them to dispute these beliefs at the same time during the disputing process. In doing so I recommend that the therapist helps the client to see clearly that they can either choose to hold an irrational belief or choose to hold a rational belief about the same adversity and that the consequences are very different. It can also be useful during the disputing process to ask the client that they have a choice of teaching the same irrational or rational belief to their children or other relevant group and to enquire what they would choose to teach and why.

Practice rB in the Session If Possible

Once the client has been helped to formulate a rational belief, then if possible, the therapist suggests that the client gains some practice at holding this rational belief during the session. This may be done within and imagery context or with some kind of rational-irrational dialogue e.g. rational role reversal (Dryden, 1995) or two chair dialogue (see Kellogg, 2015). If possible, this in-session practice should have an emotional impact on the client.

Practice rB outside the Session

While in-session rehearsal of a rational belief is desirable, what is more important is that the client commits themself to practising their rational belief in a context where they are likely to encounter their adversity at ‘A’. In doing so, they should be encouraged to act in ways that strengthen their rational belief. This context may have already been selected if the therapist was able to encourage the client to use an anticipated example of their problem. The therapist should suggest that the client rehearses this in their mind’s eye before they carry it out in reality and if there is time they should give the client an opportunity to do such rehearsal in the session. Unlike in ongoing therapy, the therapist will not get to learn the outcome of the work that they have done with the client, unless they invite the client to report back.

Generalization, If Relevant

While the REB therapist has the time in brief REBT to help the client to generalize the learning to other problems and they may have some time to do this in REBT-inspired SST, there is little if any time to do this kind of work in REBT inspired the VBTC. However, when I can I make a few closing remarks referring to generalization and suggest that the client consults these remarks either in the recording of the session or in the transcript that I routinely provide for my VBTC clients (see Dryden, 2017).

A Transcript of a VBCT Session

In what follows, I provide a verbatim transcript of an REBT-inspired VBTC held at a meeting of the United Kingdom CBT Meetup group. The conversation lasted for 10 min. I present this transcript with the full written consent of the client whose name has been changed. It gives an idea of what can be achieved in a very brief period of time.

- Windy: :

-

OK, Tony, what problem can I help you with this evening?

- Tony: :

-

I think that I suffer from chronic shame.

- Windy: :

-

Chronic shame, OK. Can you tell us a little bit about that in more detail, please?

- Tony: :

-

Sure. I was born in the mid-50s when gay activity between men was illegal. I came out to myself at the age of 12, just as the law was changing, and really kept that very much to myself as much as I could, right the way through until I was 28. So I didn’t come out until I was 28, properly. In the meantime, at university, I had a crisis, so severe depression, and was referred, initially, to the psychiatrist, who tried to convert me, unsuccessfully.

- Windy: :

-

To convert you?

- Tony: :

-

To convert me to heterosexuality.

- Windy: :

-

Right. He’d be struck off today.

- Tony: :

-

Yeah, indeed. Then a hypnotherapist had a go, and that didn’t work either. I can still remember the opening line of every hypnotherapy session was, ‘Hey Tony, are you still a homo?’ which was very affirming.

- Windy: :

-

Happy days!

- Tony: :

-

Indeed. So I seemed to achieve more equilibrium over time, but I wasn’t really noticing the amount of alcohol I was consuming. I hit rock bottom in 2000, so 17 years ago, and really was in a situation there of total crisis, and it was when I decided that sobriety was the only way forward for me, that I also realised that the only circumstances under which I could countenance a physical relationship was under the influence of alcohol.

- Windy: :

-

Which blocked what out?

- Tony: :

-

Disinhibition, really. I mean there are sexual acts – I will spare everybody’s blushes – that would make me feel uncomfortable, for example. So that disinhibiting effect, the alcohol did the trick, up to a point. Of course, it was a very negative way of coping. So the dilemma I’ve faced since then is really whether or not I’m going to come to terms, at the age of 62 now, with living my life on my own and work on my own resilience, or whether I…

- Windy: :

-

Resilience for being on your own?

- Tony: :

-

For being on my own, yes; for solitude. I don’t mean isolation, but I mean solitude in terms of a relationship that’s romantic or sexual. Or whether, in fact, this is something I should still work on. So that’s the dilemma. I’ve tried various ways, which have been partly helpful, to disinhibit myself, such as regular mindfulness practice, and so on.

- Windy: :

-

And that disinhibits you by what?

- Tony: :

-

It doesn’t disinhibit to the point where I’m actually having any sexual relationships, and I still find the whole concept, actually, quite scary. So, in some ways, I feel as if I’m 62 intellectually, but, probably, emotionally, about 15, and that’s difficult to come to terms…

- Windy: :

-

And, if we were successful this evening, what would we have achieved?

- Tony: :

-

I would feel, whatever decision I made, whether it was to work towards being more resilient in a solitary life or whether it was better to be in a relationship, I feel that I was making a free choice. At the moment, I don’t think I have the freedom to make that choice.

- Windy: :

-

Because your choice is being influenced by what?

- Tony: :

-

I think my fears are too great for me to accept the second option at the moment.

- Windy: :

-

And the chronic shame, how does that fit in?

- Tony: :

-

It’s kind of paradoxical because I do a lot of active work within and beyond the LGBT community for gay rights and so forth, and equality, and, on the one hand, I’m able to give a lot of other people, I think, a lot of support around this, but, paradoxically, I find it very hard to turn the same trick on myself, if you like.

- Windy: :

-

So is the chronic shame pushing you in the direction of one fork in the road?

- Tony: :

-

Yes.

- Windy: :

-

And which road is it?

- Tony: :

-

That’s the solitary one.

- Windy: :

-

That’s the solitary one. So the solitary fork is being driven by fear and chronic shame.

- Tony: :

-

It is, plus the fact there’s familiarity there, because now, having spent more than a quarter of my life in a solitary existence and survived so far, I know I could. I’m pretty sure I could.

- Windy: :

-

Could what?

- Tony: :

-

I could survive down that path. I’m not sure what the risks are, for example, of relapse if I go down the other route.

- Windy: :

-

Right, OK. So, if I helped you with your chronic shame, that would help you how?

- Tony: :

-

Well, I think it would unlock a lot of the processes that are going on in my mind at the moment of running against brick walls.

- Windy: :

-

So what do you feel most shamed about?

- Tony: :

-

I’m not shamed about my identity as a gay man and I feel quite comfortable to come into an environment like this, which is mixed, and share my sexual orientation. So it’s not that. I do feel shame around sexual activity, and that was also true when I had a one-off relationship with a girl; I also felt guilty about that.

- Windy: :

-

OK. So I’m going to invite you to be as honest and free as you can, and they can take care of their own blushes, alright?

- Tony: :

-

OK.

- Windy: :

-

So what sexual acts do you feel most ashamed about, if I could help you deal with the shame, that might be something you could really take forward?

- Tony: :

-

OK, well, for me, I’ve never been a receptive partner in anal sex, for example. I’ve been the active partner, again with a large amount of alcohol inside me. I wouldn’t say it was something I was totally thrilled about. I think, even with the level of inebriation, I was still conscious that it didn’t feel right. So I think there are issues around that. In terms of, if you like, activities that are probably more common to heterosexual and homosexual people, such as oral sex and other…

- Windy: :

-

OK, so what do you want to focus on: the anal or oral?

- Tony: :

-

Let’s go for anal.

- Windy: :

-

So let’s suppose that you are going to try anal sex as the penetrator. What, for you, is shameful about doing that?

- Tony: :

-

I suppose it’s a very basic notion of what the organs of the body are designed for and the notion that the anus is not designed, primarily, as a sex organ. So unnatural, I suppose, the idea of unnatural.

- Windy: :

-

Alright, so let’s suppose the act is unnatural. So you would be engaging in an unnatural act, let’s suppose. Then what do you think you’d have to tell yourself about you, Tony, to create shame about engaging in that unnatural act?

- Tony: :

-

Well, bluntly, ‘You must not commit an unnatural act.’

- Windy: :

-

Because, if you do, what kind of person are you?

- Tony: :

-

I’m not particularly religious, but sinful, I suppose, is the word I’d use.

- Windy: :

-

OK, so that’s guilt.

- Tony: :

-

Guilt, yeah.

- Windy: :

-

Let’s suppose it is a sin, it’s unnatural and sinful to act in that way, how does that make you a sinful person?

- Tony: :

-

In a global sense?

- Windy: :

-

Yeah, because that’s where guilt comes from.

- Tony: :

-

Yeah, I don’t think it does affect me in a global way.

- Windy: :

-

So why don’t you practise that, try it and see how you go in reality, because you might like it, you might not, but, if you really practise that from saying, ‘I am not a sinful person, even though some people think this is sinful and some people think it’s unnatural.’ Presumably other people don’t, right?

- Tony: :

-

Sure.

- Windy: :

-

So why couldn’t you do that, without alcohol?

- Tony: :

-

I think the way you unpicked it actually made it seem far smaller an obstacle, because you’ve kind of fragmented it: it’s not something like this, it’s now a series of…

- Windy: :

-

Because I’m saying to you and asking you to invite yourself to see that the act doesn’t identify you; you incorporate the act. How many other acts do you have to incorporate in this complex, fallible, very human organism called Tony? How many other acts do we have to include?

- Tony: :

-

Well, quite a range, if you’re talking about sexual activity, for example.

- Windy: :

-

Yeah. So, you can practise anal sex, it doesn’t define you unless you choose to allow it to define you.

- Tony: :

-

So it’s my choice?

- Windy: :

-

Yeah.

- Tony: :

-

I take your point.

- Windy: :

-

A choice that’s been…

- Tony: :

-

It’s been heavily conditioned by external factors.

- Windy: :

-

But, you see, you, as a human being, can recondition yourself. You don’t have to be a slave to that conditioning, even though you still might like it, you might not.

- Tony: :

-

But it puts me in a position of choice then, as well, doesn’t it?

- Windy: :

-

That’s right.

- Tony: :

-

So that’s a question of more freedom. That makes total sense, actually. That’s very helpful.

- Windy: :

-

So when can you put this into practice?

- Tony: :

-

I can’t give you a precise date.

- Windy: :

-

In REBT, we want specific times and dates.

- Tony: :

-

It doesn’t just involve me.

- Windy: :

-

Do you have somebody in mind?

- Tony: :

-

Not at this moment, but I think, if I work on the concept and I think, also, if I bring some of this into my mindfulness practice, that would actually be a useful thing to do.

- Windy: :

-

Yeah. How would you do that?

- Tony: :

-

Well, particularly focusing during a body scan, for example. During a full body scan you include the anus and you include the genitals, and so forth. I think, maybe, in my head, having more of a connection between the genitals and the anus would be a way of breaking down my own, if you like, internalised prejudice.

- Windy: :

-

Yeah, and to recognise that the totality of you, Tony, is not marked by your sexual activity.

- Tony: :

-

Yeah, sure.

REBT lends itself to brief therapy and in this chapter, I have outlined three different ways that REBT can be practiced when time is at a premium. With the development of online and social media platforms together with the increasing use of smartphone applications for therapeutic purposes, in my view the future is bright with respect to how REBT therapists can bring the power of REBT to increasing numbers of people – briefly!

Notes

- 1.

When Albert Ellis was alive and running these sessions, they were called ‘Friday Night Workshops’. I run a similar event in England at monthly UKCBT Meetup groups where I give a lecture on a theme and then interview two volunteers who have problems with that theme and are seeking help.

- 2.

The therapist helps the client set a goal in line with their second problem at the appropriate time later in the process.

- 3.

I refer to the volunteer as a ‘client’ throughout this section.

References

Davis, T. E., III, Ollendick, T. H., & Öst, L.-G. (Eds.). (2012). Intensive one-session treatment of specific phobias. New York, NY: Springer.

Dryden, W. (1995). Brief rational emotive behaviour therapy. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Dryden, W. (2001). Reason to change: A rational emotive behaviour therapy (REBT) workbook. Hove, UK: Brunner-Routledge.

Dryden, W., & David, D. (2009). REBT self-help form. New York: Albert Ellis Institute.

Dryden, W. (2017). Single-session integrated CBT (SSI-CBT): Distinctive features. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Dryden, W. (2018). Cognitive-emotive-behavioral coaching: A flexible and pluralistic approach. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Ellis, A. (1963). Toward a more precise definition of ‘emotional’ and ‘intellectual’ insight. Psychological Reports, 23, 538–540.

Ellis, A. (1977). Fun as psychotherapy. Rational Living, 12(1), 2–6.

Ellis, A. (1994) Reason and emotion in psychotherapy. Revised and updated edition. New York: Birch Lane Press.

Ellis, A., & Joffe, D. (2002). A study of volunteer clients who experienced live sessions of rational emotive behavior therapy in front of a public audience. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 20, 151–158.

Huber, C. H., & Backlund, B. A. (1991). The twenty minute counselor: Transforming brief conversations into effective helping experiences. New York, NY: Continuum.

Keller, G., & Papasan, J. (2012). The one thing: The surprisingly simple truth behind extraordinary results. Austin, TX: Bard Press.

Kellogg, S. (2015). Transformational chairwork: Using psychotherapeutic dialogues in clinical practice. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Mahrer, A. (Ed.). (1967). The goals of psychotherapy. New York, NY: Appleton-Century.

Reinecke, A., Waldenmaier, L., Cooper, M. J., & Harmer, C. J. (2013). Changes in automatic threat processing precede and predict clinical changes with exposure-based cognitive-behavior therapy for panic disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 73, 1064–1070.

Talmon, M. (1990). Single session therapy: Maximising the effect of the first (and often only) therapeutic encounter. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Dryden, W. (2019). Brief Interventions in Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy. In: Bernard, M.E., Dryden, W. (eds) Advances in REBT. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93118-0_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93118-0_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-93117-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-93118-0

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)