Abstract

Albert Ellis pioneered the application of rational-emotive behavior therapy (REBT) to the treatment of children and adolescents in the mid 1950s, and it has a long-standing history of application in schools. As Ellis stated, “I have always believed in the potential of REBT to be used in schools as a form of mental health promotion and with young people experiencing developmental problems” (Ellis & Bernard, 2006, p. ix). Many years ago Ellis stressed the importance of a prevention curriculum designed to help young people “help themselves” by learning positive mental health concepts that will benefit them in the present as well as in the future (Ellis, 1972).

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Albert Ellis pioneered the application of rational-emotive behavior therapy (REBT) to the treatment of children and adolescents in the mid 1950s, and it has a long-standing history of application in schools. As Ellis stated, “I have always believed in the potential of REBT to be used in schools as a form of mental health promotion and with young people experiencing developmental problems” (Ellis & Bernard, 2006, p. ix). Many years ago Ellis stressed the importance of a prevention curriculum designed to help young people “help themselves” by learning positive mental health concepts that will benefit them in the present as well as in the future (Ellis, 1972).

The educational derivative of REBT, rational-emotive behavior education (REBE) can be applied with children and adolescents individually, in classrooms and small groups, and in consultation with parents, teachers, and other school personnel (Vernon, 2007, 2009). There are now a number of “best practice” school-based programs that address social-emotional development based on REBT, including rational emotive education (Knaus, 1974), the Thinking, Feeling, Behaving curricula (Vernon, 2006a, 2006b), and You Can Do It! Education (Bernard, 2006a, 2006b, 2007, 2018a, 2018b). These programs all support Bernard’s contention (Ellis & Bernard, 2006) that teaching children social and emotional competence is essential not only for their social and emotional well-being, but also for their academic achievement, success in life, self-management, and sense of social responsibility.

REBE’s distinctiveness as a prevention, promotion and intervention approach is focused on emotional and behavioral self-awareness, self-management and change. It teaches children and adolescents rational thinking including the strengthening of rational beliefs (e.g., self-acceptance, high frustration tolerance, other-acceptance, non-approval seeking, responsible risk taking), how to challenge and re-structure irrational beliefs employing a variety of cognitive, emotional and behavioral change methods. REBT and REBE has for many years been used with parents (e.g., Çekiç, Akbas, Turan, & Hamamcı, 2016; Joyce, 1995) and teachers in a consultative role (e.g., Forman & Forman, 1980), where the emphasis is on helping them deal with their own irrational beliefs and unhealthy negative emotions that negatively impact their ability to interact appropriately with children and prevent them from being effective role models. The premise is that by helping adults deal with their own problems they in turn will be more effective parents and teachers as well as model and teach rationality to their children.

In this chapter, a brief rationale for social-emotional education programs is addressed, with specific emphasis on REBT principles that enhance development. Examples of core concepts and implementation guidelines will be described, along with a specific lesson to illustrate the process. In addition, the You Can Do It! Education program will be reviewed, with supporting research, theory, and practice. Finally, we’ll briefly review the use of REBT and REBT as a form of stress management that is employed by school counselors and psychologists.

The Rationale for Social-Emotional Education Programs

We live in a complex, rapidly-changing world that poses multiple challenges for children and adolescents as they are faced with circumstances and decisions that are often beyond their developmental capacity to deal with. Years ago psychologist David Elkind (1988) contended that youth are growing up too fast, too soon, which is much more of a reality in this contemporary society where the Internet and the media, as well as day-to-day experiences, expose youth to adult issues that they may not be far beyond their capacity to fully comprehend. A compounding factor is that children and many adolescents have not achieved formal operational thinking, which has significant ramifications for how they perceive events and predisposes them to irrational thinking in the form of overgeneralizations, frustration intolerance, demanding, and self/other downing (Vernon, 2007, 2009).

For increasing numbers of young people, dealing with typical developmental issues is overshadowed by the more serious situational problems they face, such as being victims of bullying or cyber bullying, living with increasing anxiety due to the high prevalence of violence throughout the world, or dealing with varying forms of family dysfunction including abuse and neglect, separation and divorce, substance abuse, and various types of loss. Depression, anxiety, suicide or suicide ideation, eating disorders, and substance abuse result when young people are not unsuccessful in dealing with their problems (Henderson & Thompson, 2011; Vernon, 2009).

Unfortunately, many youth will not receive mental health services, which further exacerbates the problems. Even if there is treatment, it may be costly or ineffective. For these reasons, a proactive, preventive approach is imperative. If implemented systematically in schools, all children can learn in an environment that promotes social and emotional growth, giving them “tools” that equip them to better handle life’s challenges. These types of programs help children “grow up before they give up.”

The important role and effcts of social and emotional learning skills (SELs) in student learning and well-being has been well documented (Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schellinger, 2011). The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL), a leading international organization promoting theory, research, intervention, and policy-advocacy related to SEL, identifies SEL as encompassing the following five sets of competencies (“SEL Competencies,” n.d.).

-

Self-awareness: The ability to accurately recognize one’s emotions and thoughts and their influence on behavior. This includes accurately assessing one’s strengths and limitations and possessing a well-grounded sense of confidence and optimism.

-

Self-management: The ability to regulate one’s emotions, thoughts, and behaviors effectively in different situations. This includes managing stress, controlling impulses, motivating oneself, and setting and working toward achieving personal and academic goals.

-

Social awareness: The ability to take the perspective of and empathize with others from diverse backgrounds and cultures, to understand social and ethical norms for behavior, and to recognize family, school, and community resources and supports.

-

Relationship skills: The ability to establish and maintain healthy and rewarding relationships with diverse individuals and groups. This includes communicating clearly, listening actively, cooperating, resisting inappropriate social pressure, negotiating conflict constructively, and seeking and offering help when needed.

-

Responsible decision making: The ability to make constructive and respectful choices about personal behavior and social interactions based on consideration of ethical standards, safety concerns, social norms, the realistic evaluation of consequences of various actions, and the well-being of self and others.

CASEL further defines SEL as encompassing a set of interventions at all levels of a school, designed to promote the development of those skills in continuous and coordinated ways (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, 2013).

Today, throughout many states in the United States and in many countries (e.g., Singapore, Scotland, Australia), school-based programs that teach all students that learning and acting with SEL is the norm rather than the exception (“State Standards,” n.d.; http://enseceurope.org/).

REBE is one of the oldest social and emotional learning programs (e.g., Knaus, 1974) with extensive research attesting to its effectiveness and qualifying it as a best, evidence-based practice (e.g., Bernard, 2006a; Gonzalez et al., 2004; Hajzler & Bernard, 1991). Overall findings of this research were summarized by Trip, Vernon, and McMahon (2007) as follows:

REE has a powerful effect on lessening irrational beliefs and dysfunctional behaviors, plus a moderate effect concerning positive inference making and decreasing negative emotions. The efficiency of REE appeared to not be affected by the length of applied REE. Rather, the REE effect was strong when participants were concerned with their problems. Types of psychometric measure used for irrational beliefs evaluation affected the results. Effect sizes increased from medium to large when the subjects were children and adolescents compared to young adults.

More recent research supports the positive impact of REE on a variety of negative emotions, behaviors and irrational beliefs (e.g., Caruso et al., 2018; Lupu & Iftene, 2009; Mahfar, Aslan, Noah, Ahmad, & Jaafar, 2014).

Rational-Emotive Behavioral Education (REBE)

The basic premise of REBE is that a systematic, structured curriculum based on REBT principles can empower young people to take charge of their lives to the degree that this is possible, learning how to think, feel, and behave in self-enhancing rather than in self-defeating ways. REBT is uniquely suited for a prevention program because the principles can be easily transferred into specific developmentally-appropriate lessons, the concepts can be adapted to various age groups, ethnicities, and intelligence levels, and there are numerous cognitive-behavioral techniques that can employed in creative ways, making it much easier for them to comprehend what it being presented. This skills-oriented approach helps children deal more effectively with the problems of daily life in the present as well as in the future, and these “life lessons” better equip them to apply cognitive, emotive, and behavioral strategies to lessen the severity and intensity of problems that can impede their development and their success in life.

In addition, REBT reinforces goals compatible with educational goals: critical thinking skills, problem-solving and decision-making skills, practice and persistence, self-reliance and self-responsibility, and goal setting, all, which promote achievement. As will be discussed later in this chapter, achievement is what schools are all about. Implementing REBE in schools promotes achievement by reducing emotional upset which can interfere with learning, and by teaching children and adolescents specific skills such as persistence/frustration tolerance, goal setting, rational thinking, and self-acceptance which impact their achievement.

Core REBE Concepts

The basis on an REBE program emanates from REBT principles; namely, the interrelatedness of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Teaching young people that they can control their emotions and behaviors by changing the way they think is a powerful first step in helping them learn how to reduce emotional disturbance. As they learn that it is not the event itself that “makes” them feel or behave in unproductive ways, they also need to be taught how to change their thoughts by differentiating between facts and assumptions, identifying distorted cognitions and irrational beliefs, and learning how to dispute these faulty thinking patterns. The goal is to help them think more rationally, replace unhealthy negative emotions with healthy negative emotions, and reduce or eliminate self-defeating behaviors.

The following basic concepts can be developed into specific grade-level lessons as reflected in the Thinking, Feeling, Behaving curriculums (Vernon, 2006a, 2006b):

Self Acceptance

In REBE, we distinguish between self-esteem and self-acceptance. Self-esteem implies putting a value on oneself as a good or bad person, for example. In contract, self-acceptance implies accepting oneself as a worthwhile human being who has strengths as well as weaknesses. Clearly this idea should be promoted in schools, helping students understand that as they learn new things, they will make mistakes. This doesn’t mean that they are stupid; they can learn from their mistakes and set goals for self-improvement, but they should never equate their self-worth with their performance (Vernon, 2009)

Emotional and Behavioral Consequences

As mentioned, a fundamental aspect of REBT is the emotions and behaviors result not from the event itself, but from the way one thinks about the event. It is important, therefore, that children and adolescents learn to identify how they feel and how they behave in relation to the feeling, always reinforcing the notion that they can change the way they feel and behave by changing their thoughts. Young people will need specific help in developing a feeling vocabulary, but feelings can also be inferred by helping them identify how they behaved in relation to a specific situation (Vernon, 2009).

Beliefs

Children and adolescents need to learn how to differentiate between rational and irrational beliefs. Rational beliefs are consistent with reality and are flexible and self-enhancing. They help people achieve their goals and typically result in constructive behaviors and healthy negative emotions. Irrational beliefs are illogical, rigid, and result in unhealthy negative emotions and self-defeating behaviors. Irrational beliefs manifest themselves in the forms of demands (the absolute expectation that events or people must be the way an individual wants them to be), awfulizing (exaggerating the negative consequences of a situation), frustration intolerance (things should be easy, life should be comfortable), and global evaluation of human worth (individuals can be rated and some people are worthless) (DiGiuseppe, Doyle, Dryden, & Backx, 2014). Conveying these concepts to young people can be rather difficult, so it is essential to be creative and introduce these concepts in developmentally-appropriate ways as reflected in the Thinking, Feeling, Behaving curriculums (Vernon, 2006a, 2006b) and other social-emotional education programs.

Disputing Beliefs

Disputing is the cornerstone of REBT, where irrational beliefs are replaced with rational beliefs. There are many different kinds of disputes that can be employed with children and adolescents. In addition to functional, logical, and empirical disputes, practitioners are strongly encouraged to incorporate disputational techniques into different types of developmentally-appropriate methods and reinforcing the new rational beliefs in numerous ways. For example, suppose that in a previous lesson third graders learned that everyone has strengths as well as weaknesses and that it is important not to rate themselves as an “all good or all bad.” In a follow-up lesson on disputing, the facilitator might engage them in a puppet play, where one puppet is really down on himself because he missed two spelling words on his test. The other puppet will say things like: “just because you missed two doesn’t mean you are stupid. Maybe you just didn’t study enough, or maybe you do better in other subjects.” After modeling this type of dialogue, the facilitator can ask for volunteers who will role play a different problem and “dispute” the irrational beliefs. When done in a developmentally-appropriate way, even younger children can grasp the essence of the concept, which will then be reinforced throughout the curriculum.

Implementation Guidelines

REBE can be implemented in several ways within the school setting: through social-structured emotional education lessons, integration into the curriculum, the teachable moment, and integration into the total school environment. While each has its merits, the structured emotional education lesson sequence is the “gold standard” – the preferred method – because REBE concepts are specifically taught so that children learn the theory and how to put it into practice. The other three methods are excellent ways of reinforcing these principles. In order to deliver a comprehensive program of this nature, it is imperative that teachers and other school personnel clearly understand the REBE philosophy, so teacher in-service is essential.

Structured REBE Lessons

These lessons can be presented in classrooms or in small-group psycho-education counseling sessions. The lessons should be presented in a sequential manner so that the core concepts are introduced in grade 1 and then re-introduced and reinforced throughout elementary, middle school and high school, with the lessons reflecting developmentally-appropriate ways of presenting the ideas. These lessons should be engaging, creative, and experiential, with a great deal of student involvement and group interaction. This increases the likelihood that children will develop a good understanding of the concepts because they are presented and reinforced in various ways to appeal to auditory, visual, and kinesthetic learners.

Having a well-developed lesson is essential, and I (AV) recommend the following:

-

(a)

Develop 2–3 specific objectives, which are grade-level appropriate for each lesson.

-

(b)

Present a short stimulus activity to introduce the content and engage learners in the lesson. Examples of stimulus activities include games, art and music activities, writing and worksheets activities, drama, experiments, bibliotherapy, or role playing. The stimulus activity presents the content of the lesson that corresponds to the objectives identified for the lesson.

-

(c)

Process the stimulus activity by engaging students in a discussion based on two types of questions: content questions and personalization questions. Content questions refer to the concepts that were presented in the stimulus activity. For example, if the facilitator had read a book to elementary-age children about anxiety, What If It Never Stops Raining? (Carlson, 1992), the questions would reflect the content of the book: “What did the boy in the story worry about? Did all of things he worried about actually occur? And if they did, was it as bad as he thought it would be? What did the boy in the story learn about worrying so much?” Personalization questions help them apply the concepts to their own lives. For example, “Do you ever worry a lot like the character in this story? Do the things you worry about usually come true? If they come true, are they as bad as you thought they would be? What are some of the things you do or could do to help you deal with your worries?” The emphasis in on practical application of the concepts, so it is important to allow adequate time for discussion.

An example of a lesson for middle school students is described below to give readers a better idea of an emotional education lesson on the topic of irrational beliefs, entitled Rose Colored Glasses (adapted from Vernon, 2006a, pp. 241–244).

-

Objective: To identify the effects of rational versus irrational thinking.

-

Materials needed: Two pair of glasses, one with the lenses covered in black construction paper and the other pair in pink paper.

-

Procedure/Stimulus Activity:

-

1.

Review the concept of rational versus irrational thinking and explain that when we think irrationally, we often fail to differentiate facts from assumptions and we overgeneralize and awfulize, making things seem worse than they actually are. It is like “doom and gloom” thinking, where everything seems bad. Then contrast that with rational thinking characterized by looking at the facts and thinking logically and realistically, which can result in a positive as opposed to a negative perspective.

-

2.

Divide the students into two groups and give one group the rose colored glasses (and have a volunteer put them on) and do the same for the group with the dark glasses. Inform them that you will be describe an event and in their groups, they are to generate responses about how they might think, feel, and behave relative to that event, based on the glasses they are wearing.

-

3.

Read examples such as the following, but before moving to the next example, have each group share and compare their responses with regard to thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Examples include: your best friend doesn’t sit by you at lunch; your parents won’t let you invite a particular friend over to spend the night; you don’t get a good grade on an assignment; your sister refuses to do her share of chores and you get blamed for it.

-

4.

Discuss the content questions:

-

Do you see a difference between the way you think, feel and act when you have the dark glasses on as opposed to the rose-colored ones? What were some of the differences?

-

Which kind of thinking is more helpful? Why?

Discuss the personalization questions:

-

Which kind of thinking do you typically practice?

-

What have been your experiences with the effects of irrational thinking?

-

If you wanted to change the way you think, how would you go about doing it? What do you think would be the results? What did you learn from this activity?

-

-

1.

Integration into Subject Matter

This is another viable way to reinforce principles learned from the structured lessons. With this approach, teachers integrate rational concepts into subject matter curriculum. For example, topics for writing assignments could include what it is like to make a mistake, what they consider to be personal strengths and weaknesses, or an example of a time when they thought through consequences of their behavior versus a time they did not. Vocabulary and spelling lessons could include feeling-word vocabularies and definitions. Social studies lessons could focus on facts versus assumptions as they relate to political campaigns or to the concept of fairness as it relates to oppressed groups throughout history. Frustration tolerance can be addressed by reading about how soldiers struggled during wars or by discussing examples from current events. As noted, although this is a less direct approach, the integration of these concepts into the regular curriculum has numerous benefits.

The Teachable Moment

The assumption here is that teachers (and hopefully parents) will take advantage of teachable moments to introduce or reinforce rational concepts. This can be done with individuals, a small group, and an entire classroom. For example, when my son was playing his first football game in middle school, the team anticipated winning, but they lost. When I picked him up after the game he said that everyone felt terrible and that some boys were even crying because they thought it was their fault that the team lost. I asked what the coach did or said on the bus on the way back to the school, and he said that he didn’t say a word. This would have been an ideal teachable moment, asking the boys how they felt, helping them understand that this was a team effort and not the fault of one or two individuals, that it was their first game and so it was likely that they would make some mistakes but could learn from them, and that one loss didn’t mean that they were a horrible team. This might have taken all but 5 minutes but could have had a major impact on how they responded to the next loss!

The “teachable moment” approach can be used in many different ways. Suppose you are a teacher and you are giving your class a test. Just before the students put away their books and get ready to take the exam you ask for a show of hands as to how many are nervous about taking this test and then how many aren’t that anxious. Contrast the two positions by asking what the students who are anxious are thinking versus those who are not as anxious. Briefly explore these thoughts and help them see that if they don’t think catastrophically (I won’t pass, it will be terrible) or put themselves down if they do poorly (if I don’t pass it proves that I’m an idiot) they will be less anxious and can do a better job concentrating on the exam. Although this is a short intervention, it is very helpful. Or, suppose you are walking down the hall and you see two students arguing in the hallway. As you approach them you hear one student berate the other, calling her a loser and a liar. Suddenly this girl hauls off and hits the name caller, and she in turn starts hitting back, spewing out more unsavory names. You pull them aside and ask the girl who was called “loser and liar” how she felt about being called names. She said she was angry and that the other girl shouldn’t have called her a name. You agree with her, noting that it is a school rule, but asking her if people sometimes break rules? And even if she didn’t like being called names, is she really a loser and a liar? After processing this for awhile and diffusing the fight, you can also help the “victim” see that she even though she didn’t like being called names, she had a choice about how to think about it, helping her see how her thinking impacted her feelings and her behavior. You also work with the bully to help her examine her behavior – would she like it if others called her names? And what did she gain from doing it since she had to serve detention for breaking a rule? Short intervention such as these introduce and/or reinforce rational principles.

To use this approach, teachers have to have a good understanding of REBT concepts and rather lecture students, they engage them in a discussion which helps students learn to think more rationally, which in turn impacts their feelings and their behaviors and promotes more effective problem-solving.

Total School Environment

It is important that the key concepts previously described are reflected in the total school environment so that there is congruence between what is being presented in the social-emotional education curriculum and what is reinforced through school practices and procedures. For example, many schools give awards for best performance, but to be consistent with REBT, it is important to have a variety of awards, not only for good performance, but also for persistence and practice, most improved performance, and so forth. Another example would be to de-emphasize competition and the “winner/loser” notion in games, focusing instead on things each team did well and what they could do to improve, which reinforces the notion that everyone has strengths as well as weaknesses. An additional way to reinforce these concepts would be for teachers in each classroom to nominate a “student of the week,” someone who demonstrated good behavior management, anger management, or problem-solving skills. The nominated students could be acknowledged at a school-wide assembly each month and the 4 students per class could make rational posters and banners to present at the assembly with words or phrases describing what they did to deserve the nomination and what rational thoughts helped them demonstrate good behavior management and problem-solving skills.

REBT has always championed an educative, preventative focus, which is particularly relevant for use in schools. The importance of a social-emotional education curriculum cannot be stressed enough, and the research clearly connects healthy development to school achievement.

You Can Do It! Education

You Can Do It! Education is one of a number of social-emotional learning programs that derive in part from the theory and practice of rational emotive education. As can be see in Fig. 13.1, Bernard (e.g., 2013), the theory of You Can Do It! Education identifies 12 irrational beliefs referred to as Negative Habits of the Mind (Attitudes) that give rise to five social-emotional blockers (feeling very angry/misbehaving, not paying attention/disturbing others, procrastination, feeling very worried, feeling very down) and 12 rational beliefs called Positive Habits of the Mind (Attitudes) that are associated with five social-emotional skills (confidence, persistence, organization, getting along, resilience).

You Can Do It! Education’s social and emotional learning framework (Bernard, 2007)

There are a number of different ways that the 5 Social-Emotional Skills and the 12 Attitudes are taught in YCDI including: YCDI curricula programs, YCDI classroom and school-wide practices, and YCDI parent education. Of particular interest are the YCDI curriculum programs for students in pre-school and grades 1–12 that teach students depending on their developmental level the ABCs of REBT, how to distinguish, challenge and change irrational beliefs to rational beliefs as well as additional emotional and problem solving skills

YCDI Curricula Programs

There are four YCDI! Education social-emotional curricula that are used extensively in schools.

-

1.

The You Can Do It! Education Early Childhood Program (ages 4–7) (Bernard, 2018a) that is used in over 2500 kindergarten and year 1 classrooms.

-

2.

Program Achieve (ages 6–18) (Bernard, 2018b) is a curriculum series used in over 4000 primary and secondary schools.

-

3.

Bullying: The Power to Cope (ages 9–16) (Bernard, 2016b) is A four-part program designed to be taught by teachers and mental health practitioners to classroom groups of students between grades 4–9.

-

4.

The You Can Do It! Education Mentoring Program (Bernard, 2014) consists of activities that are designed to be presented to a student by a coach, mentor or teacher. The activities are designed to strengthen the student’s core social-emotional skills (confidence, persistence, organization, getting along and resilience).

YCDI Classroom- and School-Wide Practices

In addition to teachers presenting lessons and activities from YCDI’s curricula programs, over the years a number of different teaching practices have been identified that help develop students’ knowledge and use of the 5 Foundations and the 12 Habits of the Mind (see Bernard, 2006b). Some of these practices include:

-

Practice 1. Have Discussions with Students About Each of the 5 Foundations

-

It is important for teachers to have conversations about each of the 5 Foundations and how important each is to everyone’s success and well-being. Teachers should engage students in a discussion of the Foundations asking them for their views/definitions and making sure that at the end of the discussion, a definition is provided.

-

-

Practice 2. Describe to Students Examples of Behaviours to Be Practised that Reflect Each Foundation

-

After discussion, teachers should display on a poster a list of examples of behaviours of each of the 5 Foundations that students will need to practise in order to develop the Foundations (e.g. practicing times tables, spending time doing research in the library, practicing spelling, spending time reading). Teachers encourage students to practise these behaviours.

-

-

Practice 3a. Teach Students about the Important Role of Thinking/Self-Talk to Their Feelings and Behaviour

-

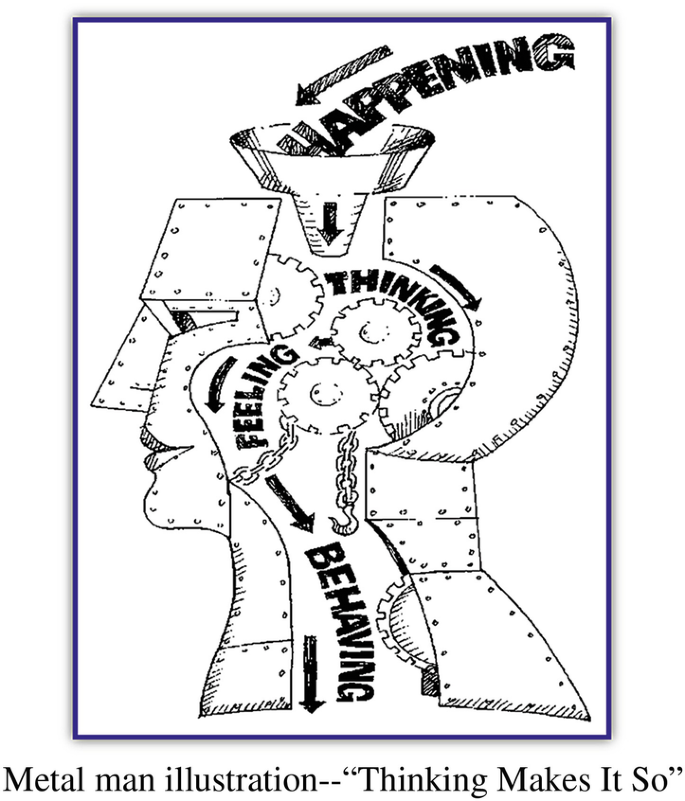

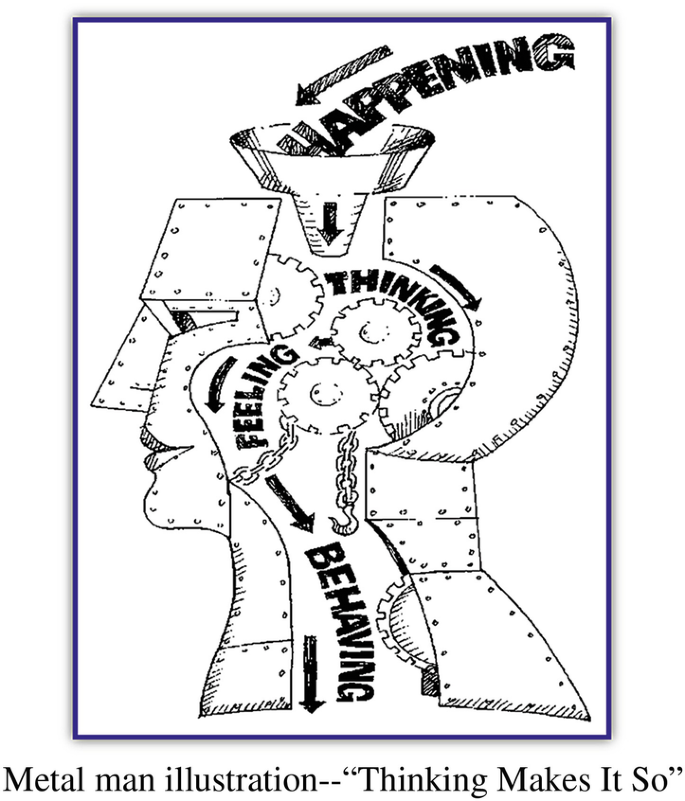

One of the important ideas to impart to students is that it is not what happens to them that determines how successful and happy they are. This idea has been around for some time. Epictetus, a Stoic-Roman philosopher, wrote in the second century A.D. that ‘People are not affected by events, but by their view of events.’ Shakespeare wrote that ‘Things are neither good nor bad, but thinking makes them so.’

-

-

-

Practice 3b. Discuss with Students the Positive Habits of the Mind that Support Each of the 5 Foundations

-

Teachers will want to provide students with opportunities to learn the meaning of 12 positive Habits of the Mind and how they support the 5 Foundations. Teachers will want to illustrate through discussion and role-play how a positive Habit of the Mind can help someone to practise positive behaviour.

-

-

Practice 4. Provide Students with Behaviour-Specific Feedback When They Display Examples of the Behaviours that Reflect the 5 Foundations

-

When teachers catch a student practicing a behaviour that reflects the Foundation they are teaching, teachers should acknowledge the student verbally, non-verbally, or in a written comment (e.g. ‘You were confident.’ ‘You tried hard and did not give up. That’s persistence.’ ‘Doesn’t it feel good to be organised?’ ‘You are getting along very well when working together.’ ‘You stayed calm in a difficult situation. That’s resilience.’).

-

-

Practice 5. Teach Students Not to Blow Things out of Proportion

-

This is a very popular teaching practice that helps develop students’ resilience. Teachers discuss with students how there are different degrees of ‘badness’. Some things are ‘a bit bad’, some things are ‘bad’, some things are ‘very bad’, and some things are ‘awful and terrible’. Teachers explain to students that when ‘bad’ things happen to them, they should use their thinking to mentally place the negative events in the correct category of ‘badness’ and not to blow the badness of the event out of proportion.

-

-

Practice 6. Integrate YCDI in the Academic Curriculum

-

The more teachers can incorporate the Foundations and the Habits of the Mind in other activities of their class or in one-to-one mentoring discussions, the more rapidly students will internalise them. A popular activity in Language Arts is for students to identify a character from a book they are reading or a movie they have seen and conduct a character analysis using key YCDI concepts.

-

-

Practice 7. Integrate YCDI in Art, Music and Drama

-

YCDI should be expressed in the artwork and music that is found in school. Art classes can design murals and posters that illustrate the 5 Foundations and which can then decorate the school. Students create their own songs and plays to bring the YCDI themes to life. There are a range of YCDI songs created by Kevin Hunt and myself that communicate different social-emotional skills and rational attitudes taught in YCDI (‘I’m feeling confident today’; ‘I’ll be persistent’) for elementary-age students and a series for young children (e.g. ‘I’m Connie Confidence’).

-

Here is a list of recommended actions that experience has shown will build the critical mass needed for YCDI to become an intrinsic part of school culture so that all students are influenced.

-

1.

Awards. Existing awards for student behaviour (classroom, school-wide) can be modified so that students are ‘caught’ and acknowledged by their teachers for displaying confidence, persistence, organisation, getting along and resilience.

-

2.

Assemblies. Assembly time can be used to invite speakers to talk to students about the importance of the 5 Foundations and 12 Habits of the Mind in their lives.

-

3.

Excursions. Adults who take students on excursions can prepare students for successful outings by reviewing in advance with students how the different YCDI Foundations can make their excursion a success.

-

4.

Celebration of Student ‘Success’ Stories. These stories should be shared on a regular basis at staff meetings.

-

5.

School/Classroom Signage. The five YCDI Foundations can be displayed in the library, reception area, corridors, and inside/outside walls and in select spots around the school grounds. These can be creative contributions made by school parents or teachers.

-

6.

Assessment. For students and staff to take YCDI seriously, it is good practice for students to be formally assessed by their teachers on the school’s report card in terms of their display of their social and emotional learning skills.

Summary of Research on You Can Do It! Education

Over two decades of published research studies show that You Can Do It! Education is a proven, “best-practice” set of programs for enhancing the achievement and well-being of young people.

-

When You Can Do It! Education was implemented throughout seven primary schools where positive attitudes and social-emotional skills were taught using a variety of classroom and whole-school practices including the Program Achieve social-emotional learning curriculum, the social-emotional well-being of students improved in comparison with students enrolled in similar schools where You Can Do It! Education was not implemented (Bernard & Walton, 2011).

-

Four evaluation studies (3 in primary schools; 1 in high school) that examined the effects of You Can Do It Education in a whole school, multiple classrooms, in tutorial groups and in an after-school coaching showed positive effects on the grades, effort and quality of homework and school attendance (Bernard, Ellis, & Terjesen, 2006).

-

When the You Can Do It! Education Early Childhood Program was taught to grade 1 students with a focus on strengthening confidence, persistence, organization, getting along and resilience, a positive impact was found on students’ well-being, social skills and reading comprehension (students in lower 50% of class) in comparison with students who were not taught the program (Ashdown & Bernard, 2012).

-

When You Can Do It! Education’s program, Bullying: The Power to Cope designed to teach positive attitudes and coping skills was taught to students in primary schools, the impact of bullying (cyber-, verbal, physical, isolation) on their emotions and thinking (cognitive) was much less severe in comparison with students who are not taught the program (Markopolous & Bernard, 2015).

-

When You Can Do It! Education’s curriculum, Program Achieve, was taught to students with achievement, behavioral, social and/or emotional challenges, these ‘at risk’ students show strengthened resilience in comparison to a group of ‘at risk’ who did not participate (Bernard, 2008).

-

When the You Can Do It! Education program, Attitudes and Behaviours for Learning (AB4L), was taught by teachers to students who are in the lower 50% of their class in reading, their reading achievement improved in comparison with the reading level of students not taught the program (Bernard, 2017b).

REBT and Teacher Stress

Since the 1980s (e.g., Bernard, Joyce, & Rosewarne, 1983), 1990s (Forman, 1994) and continuing to the present day (e.g., Bernard, 2017a; Warren & Hale, 2016). REBT has been deployed in professional development for teachers, in individual coaching programs and in pre-service teacher education programs (e.g., Nucci, 2002; Steins, Haep, & Wittrock, 2015) to help manage stress.

Bernard devised The Teacher Irrational Belief Scale (TIBS) (see Bora, Bernard, & Decsei-Radu, 2009) that revealed strong associations between irrationality and high amounts of teacher stress (Bernard, 2016a). Employing a sample of 850 primary and secondary teachers in Australia, Bernard, 2016a conducted an exploratory factor analysis of the TIBS that resulted in four distinct factors: Self-Downing, Authoritarianism, Demands for Justice, and Low Frustration Tolerance. In a second study, 140 teachers and 26 teachers retired from teaching because of stress completed the TIBS and a measure of teacher stress. Teachers retired from teaching due to stress scored higher on sub-scales of Self-Downing and Low Frustration Tolerance than teachers still teaching.

Professional development stress management programs that incorporate REBT teach the basic ABC including how to recognize, challenge and change irrational beliefs. What follows is an example of such a program offered by consultants (school psychologists, counselors) (from Warren & Hale, 2016):

-

Session 1 Topic: Introduction to Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy

-

Objectives: To gain an understanding of the history of REBT; to become aware of the efficacy of REBT; to build an awareness of the value of utilizing counseling theory in classroom; to learn principle basic principles of REBT and how they apply to classroom situations

-

Session 2 Topic: Rational-Emotive Philosophy and Theory

-

Objectives: To gain awareness of knowing verses thinking; to understand the values and goals of REBT; to learn and apply the concepts presented related to rational and irrational beliefs

-

Session 3 Topic: Rational-Emotive Behavior Therapy

-

Objectives: To become aware of the three major “musts” and their derivatives; to explore the belief-consequence connection; to learn the ABC Model of Emotional Disturbance; to apply the ABC Model to personal and professional situations

-

Session 4 Topic: The ABC Model Expanded

-

Objective: To learn the expanded version of the ABC Model; to learn the value of disputing irrational beliefs; to acquire cognitive techniques and strategies for challenging irrational beliefs; to implement and practice the strategies provided

-

Session 5 Topic: Disputing Irrational Beliefs

-

Objectives: To learn additional cognitive challenges for irrational beliefs; to learn emotional and behavioral disputes; to apply strategies and techniques for challenging irrational beliefs

-

Session 6 Topic: Classroom Applications of REBT

-

Objectives: To further learn how to apply REBT to classroom situations; to learn cognitive-behavioral strategies and techniques specific to classroom scenarios.

Conclusion

The theory and practice of rational emotive behavior therapy and its application in the form of rational emotive behavior education and consultation for stress management continues to benefit student and teacher outcomes. It can be seen from this chapter that rationality is a precious human commodity that when under-developed is associated with a myriad of social and emotional difficulties of students as well as stress in teachers. We hope that the evident benefits of strengthening rationality a well as the relatively straightforward methods for doing so will encourage educators and mental health practitioners who teach and consult in schools to promote rationality for all.

References

Ashdown, D. M., & Bernard, M. E. (2012). Can explicit instruction in social and emotional learning skills benefit the social-emotional development, well-being, and academic achievement of young children? Early Childhood Education Journal, 39, 397–405.

Bernard, M. E. (2006a). Providing all children with the foundations for achievement, well-being and positive relationship (3rd ed., p. 286). Oakleigh, VIC, Australia: Australian Scholarships Group; Priorslee, Telford (ENG): Time Marque.

Bernard, M. E. (2006b). It’s time we teach social-emotional competence as well as we teach academic competence. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 22, 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573560500242184

Bernard, M. E. (2007). Program achieve. A social and emotional learning curriculum (3rd ed.). (Primary Set, six vols.: Ready Set, You Can Do It!, Confidence, Persistence, Organisation, Getting Along, Resilience). Oakleigh, VIC, Australia: Australian Scholarships Group; Priorslee, Telford (ENG): Time Marque, pp. 1200.

Bernard, M. E. (2008). The effect of You Can Do It! Education on the emotional resilience of primary school students with social, emotional, behavioral and achievement challenges. Proceedings of the Australian Psychological Society Annual Conference, 43, 36–40.

Bernard, M. E. (2013). You Can Do It! Education: A social-emotional learning program for increasing the achievement and well-being of children and adolescents. In K. Yamasaki (Ed.), School-based prevention education for health and adjustment problems in the world. Tokyo, Japan: Kaneko Shobo.

Bernard, M. E. (2014). The You Can Do It! Education mentoring program (p. 180). Oakleigh, VIC, Australia: Australian Scholarships Group; Priorslee, Telford (ENG): Time Marque.

Bernard, M. E. (2016a). Beliefs and teacher stress. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 34, 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-016-0238-y

Bernard, M. E. (2016b). Bullying: The power to cope. Oakleigh, VIC, Australia: Australian Scholarships Group.

Bernard, M. E. (2017a). Stress management for teachers and school principals. Oakleigh, VIC, Australia: Australian Scholarships Group.

Bernard, M. E. (2017b). Impact of teaching attitudes and behaviors for learning on the reading achievement of students falling behind. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 16, 51–64.

Bernard, M. E. (2018a). Program achieve. A social emotional learning curriculum for young children. Melbourne, VIC, Australia: The Bernard Group.

Bernard, M. E. (2018b). The NEW program achieve. Attitudes and social-emotional skills for student achievement, behaviour and wellbeing. Melbourne, VIC, Australia: The Bernard Group.

Bernard, M. E., Ellis, A., & Terjesen, M. (2006). Rational-emotive behavioral approaches to childhood disorders: History, theory, practice, and research. In A. Ellis & M. E. Bernard (Eds.), Rational emotive behavioral approaches to childhood disorders: Theory, practice and research (pp. 3–84). New York, NY: Springer.

Bernard, M. E., Joyce, M. R., & Rosewarne, P. (1983). Helping teachers cope with stress. In A. Ellis & M. E. Bernard (Eds.), Rational-emotive approaches to the problems of childhood (pp. 415–466). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Bernard, M. E., & Walton, K. E. (2011). The effect of You Can Do It! Education in six schools on student perceptions of wellbeing, teaching-learning and relationships. Journal of Student Well-being, 5, 22–37.

Bora, C., Bernard, M. E., & Decsei-Radu, A. (2009). Teacher irrational belief scale – Preliminary norms for Romanian population. Journal of Cognitive and Behavioral Psychotherapies, 9, 211–220.

Carlson, N. (1992). What if it never stops raining? New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Caruso, C., Angelone, L., Abbata, E., Ionni, V., Biondi, C., Agostino, C. D., … Mezzaluna, C. (2018). Effects of a REBT based training on children and teachers in primary school. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 36, 1–14.

Çekiç, A., Akbas, T., Turan, A., & Hamamcı, Z. (2016). The effect of rational emotive parent education program on parents’ irrational beliefs and parenting stress. Journal of Human Sciences, 13, 1. https://doi.org/10.14687/ijhs.v13i1.3729

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. (2013). 2013 CASEL guide: Effective social and emotional learning programs: Preschool and elementary school edition. Chicago, IL: Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning.

DiGiuseppe, R., Doyle, K. A., Dryden, W., & Backx, W. (2014). A practitioner’s guide to rational emotive behavior therapy (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Durlak, J., Weissberg, R., Dymnicki, A., Taylor, R., & Schellinger, K. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta- analysis of school- based universal interventions. Child Development, 82, 474–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Elkind, D. (1988). The hurried child: Growing up too fast too soon. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Ellis, A. E. (1972). Emotional education in the classroom: The living school. Journal of Child Psychology, 1, 19–22.

Ellis, A. E., & Bernard, M. E. (2006). Rational emotive approaches to the problems of childhood (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer.

Forman, S. (1994). Teacher stress management: A rational-emotive therapy approach. In M. E. Bernard & R. D. DiGiuseppe (Eds.), Rational-emotive consultation in applied settings. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Forman, S. G., & Forman, B. D. (1980). Rational-emotive staff development. Psychology in the Schools, 17, 90–95.

Gonzalez, J. E., Nelson, J. R., Gutkin, T. B., Saunders, A., Galloway, A., & Shwery, C. S. (2004). Rational emotive therapy with children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 12, 222–235.

Hajzler, J. D., & Bernard, E. M. (1991). A review of rational-emotive education outcome studies. School Psychology Quarterly, 6, 27–49.

Henderson, D. A., & Thompson, C. L. (2011). Counseling children. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Joyce, M. R. (1995). Emotional relief for parents: Is rational-emotive parent education effective? Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 13, 55–75.

Knaus, W. J. (1974). Rational emotive education: A manual for elementary school teachers. New York, NY: Institute for Rational Living.

Lupu, V., & Iftene, F. (2009). The impact of rational emotive behaviour education on anxiety in teenagers. Journal of Cognitive and Behavioral Psychotherapies, 9, 95–105.

Mahfar, M., Aslan, A. S., Noah, S. M., Ahmad, J., & Jaafar, W. M. W. (2014). Effects of rational emotive education module on irrational beliefs and stress among fully residential school students in Malaysia. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 114, 239–243.

Markopolous, Z., & Bernard, M. E. (2015). Effect of the bullying: The power to cope program on children’s response to bullying. Journal of Relationships Research, 6, 1–11.

Nucci, C. (2002). The rational teacher: Rational-emotive behavior therapy in teacher education. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, 20, 15–32.

Steins, G., Haep, A., & Wittrock, K. (2015). Technology of the self and classroom management – A systematic approach for teacher students. Creative Education, 6, 2090–2104. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2015.619213

Trip, S., Vernon, A., & McMahon, J. (2007). Effectiveness of rational-emotive education: A quantitative meta-analytical study. Journal of Cognitive & Behavioral Psychotherapies, 7(1), 81–93.

Vernon, A. (2006a). Thinking, feeling, behaving: An emotional education curriculum for children (2nd ed.). Champaign, IL: Research Press.

Vernon, A. (2006b). Thinking, feeling, behaving: An emotional education curriculum for adolescents (2nd ed.). Champaign, IL: Research Press.

Vernon, A. (2007). Application of rational emotive behavior therapy to groups within classrooms and educational settings. In R. W. Christner, J. L. Steward, & A. Freeman (Eds.), Handbook of cognitive-behavior group therapy with children and adolescents: Specific settings and presenting problems (pp. 107–127). New York, NY: Routledge.

Vernon, A. (2009). More what works when with children and adolescents: A handbook of individual counseling techniques. Champaign, IL: Research Press.

Warren, R., & Hale, R. W. (2016). The influence of efficacy beliefs on teacher performance and student success: Implications for student support services. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 34, 187–208.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Vernon, A., Bernard, M.E. (2019). Rational Emotive Behavior Education in Schools. In: Bernard, M.E., Dryden, W. (eds) Advances in REBT. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93118-0_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93118-0_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-93117-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-93118-0

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)