Abstract

Emotional processes are of key importance for the understanding of narcissism, in both its grandiose and its vulnerable forms. The current chapter provides an overview on the links between narcissism and emotionality. The two forms of narcissism differ distinctly in their hedonic tone, with vulnerable narcissism being characterized by negative emotionality and low well-being and grandiose narcissism being linked to positive emotionality and high well-being. Both forms are related to strong mood variability that is thought to stem from contingent self-esteem. Both forms are related to hubristic pride, but only vulnerable narcissism is linked to shame-proneness, envy, and schadenfreude. Both forms are characterized by outbursts of anger, but the underlying causes and the expression of anger differ between the two forms. Specifically, vulnerable narcissism is linked to uncontrollable narcissistic rage that stems from a fragile sense of self and results in disproportionate and dysfunctional aggression. Grandiose narcissism, in contrast, goes along with instrumental aggression that serves the purpose of asserting one’s dominance in the face of strong direct status threats. Vulnerable narcissism is related to deficits in emotion regulation, yet research has just begun to shed light on the regulation processes of grandiose narcissists. The chapter concludes with reflections on how recent theoretical and methodological developments might be employed to gain a fuller understanding of narcissists’ emotional lives.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Narcissism

- Emotions

- Subjective well-being

- Hubristic and authentic pride

- Shame

- Envy

- Schadenfreude

- Narcissistic rage

- Emotion regulation

- Emotion contagion

The central theme of narcissism is self-importance, and its most essential features are a preoccupation with the self and an inflated sense of one’s own importance and deservingness (Krizan & Herlache, 2018). Depending on whether narcissism takes on a grandiose or vulnerable form (Miller et al., 2011; Pincus et al., 2009; Wink, 1991), it can be associated with emotional experiences of different valence, strength, dynamic, and expression. In this chapter, we describe the common and universal as well as the more diverse aspects of emotional life specific to grandiose and vulnerable narcissism.

General Emotionality and Subjective Well-Being

One likely determinant of narcissists’ general emotionality is their orientation toward approach versus avoidance behavior. Approach orientation typically goes along with positive emotionality, and avoidance motivation is accompanied by negative emotionality (Elliot & Thrash, 2002). Research has shown that grandiose narcissists are approach oriented and sensitive to rewards, whereas vulnerable narcissists are avoidance oriented and sensitive to threats (Campbell & Foster, 2007; Foster & Trimm, 2008; Krizan & Herlache, 2018; Pincus et al., 2009). Accordingly, the two forms have remarkably diverse affective correlates. Grandiose narcissists tend to be in an energetic, upbeat, and optimistic mood (Sedikides, Rudich, Gregg, Kumashiro, & Rusbult, 2004), whereas vulnerable narcissists tend to experience negative affect and anxiety (Tracy, Cheng, Martens, & Robins, 2011).

In a meta-analysis, Dufner, Gebauer, Sedikides, and Denissen (in press) found a low but positive average correlation (r = 0.13) between grandiose narcissism and a personal adjustment composite score consisiting of high subjective well-being and low depression. Other research has reported negative correlations between grandiose narcissism and specific indicators of negative emotionality, such as sadness, depression, loneliness, anxiety, and neuroticism (e.g., Dufner et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2011; Rose, 2002; Sedikides et al., 2004). Thus, grandiose narcissists are typically happy and have been described as “successful narcissists” (Back & Morf, 2018). Sedikides et al. (2004) showed that high self-esteem mediated the link between grandiose narcissism and well-being, which indicates that grandiose narcissists are high in well-being mainly due to their high self-esteem. This implies, however, that any factor that lowers narcissists’ self-esteem is also likely to reduce their well-being. Zajenkowski and Czarna (2015) showed that grandiose narcissists’ well-being might depend on their self-evaluation in an agentic domain. Specifically, when grandiose narcissists have low intellectual self-esteem, their well-being was lower than among people low in grandiose narcissism. Thus, grandiose narcissists are happy as long as they manage to maintain high agentic self-esteem.

Vulnerable narcissism , in contrast, is inversely associated with subjective well-being (Rose, 2002). It predicts a number of variables related to negative emotionality, such as anxiety, depression, and hostility (Miller et al., 2011), earning vulnerably narcissistic individuals the name “struggling narcissists” or even “failed narcissists” (Back & Morf, 2018; Campbell, Foster, & Brunell, 2004). Recently, Miller et al. (2017) have shown that vulnerable narcissism is almost entirely reducible to neuroticism (the rest being antagonism and hostility) which is a strong and negative predictor of subjective well-being (Diener & Lucas, 1999). All these findings suggest that vulnerable narcissism is associated with low psychological well-being.

Even though grandiose and vulerable narcissism differ in their overall relations to well-being, they are both characterized by strong mood variability, which is thought to be due to their contingent self-esteem and sensitivity to social comparisons (Bogart, Benotsch, & Pavlovic, 2004; Geukes et al., 2017; Krizan & Bushman, 2011; Rhodewalt, Madrian, & Cheney, 1998; Rhodewalt & Morf, 1998). Grandiose narcissists’ state self-esteem decreases substantially on days with more negative achievement events, leading to rapidly changing emotions (Zeigler-Hill, Myers, & Clark, 2010). Similarly, when confronted with shameful interpersonal experiences, such as relational rejections, vulnerable narcissists react in comparable ways (Besser & Priel, 2010; Sommer, Kirkland, Newman, Estrella, & Andreassi, 2009; Thomaes, Bushman, Stegge, & Olthof, 2008). Hence, even though grandiose and vulnerable narcissists might be particularly sensitive to different types of self-esteem threats, they both react to these threats with strong mood variability.

Pride and Shame

The “authentic versus hubristic” model of pride by Tracy and Robins (2004, 2007a) emphasizes the role of emotional processes underlying narcissistic self-esteem. Narcissism, in both its grandiose and vulnerable versions, is characterized by a constant interplay of excessive pride and shame, two self-conscious emotions (Tracy et al., 2011). In the model proposed by Tracy, Cheng, Robins, and Trzesniewski (2009); Tracy et al. (2011), shame is a core affect in narcissism, and it is typically followed by a response of self-aggrandizement and pride, a mask of self-confidence covering an embarrassed face. However, many recent data question the central role of shame in narcissism, at least in its grandiose form. Therefore, below, we first present the original model described by Tracy et al. (2009, 2011), and further we point to some of its limitations.

Tracy and Robins (2004, 2007a) argued that pride has different facets, and only one of them is associated with narcissism, namely, hubristic pride. Tracy and Robins (2007b) suggested that authentic pride is based on real achievements and leads to the development of genuine self-esteem . Conversely, hubristic pride stems not from actual accomplishments, but from generalized, distorted positive views of the self. Narcissism, both in the grandiose and vulnerable version, is typically linked with hubristic pride (Tracy et al., 2009, 2011; Tracy & Robins, 2004, 2007a). Hubristic pride in narcissism is an emotional experience fueled by self-enhancement and an inauthentic sense of self. According to Tracy et al. (2009, 2011), positive views of the self are too essential for the narcissist to leave them to the whim of actual accomplishments, for these views are what prevents the individual from succumbing to the excessive and global shame. It has been suggested that narcissistic self-aggrandizement is a result of an internal conflict developed in early childhood when parents place unrealistic demands on a child and reject him/her when perfection is not achieved (Tracy et al., 2009). A child may then develop a dissociation between positive (explicit) and negative (implicit) self-representations (Kohut, 1971). This process creates a ground for an interplay between shame and pride. Specifically, failures lead to overwhelming shame because they feed into the negative implicit self-representations. As a defense against excessive shame, narcissists harbor their positive explicit self-representations and idealize the explicit self, which manifests in stable, global attributions following success (“I did it because I am always great”). Thus, the positive, explicit self becomes an object of pride. To travesty William Blake’s words: “Pride is shame’s cloak.”

Narcissists regulate self-esteem by decreasing the likelihood of shame experience and, simultaneously, by increasing the likelihood of hubristic pride experience. They also try to maintain high self-esteem through external indicators of their self-worth (e.g., other people’s admiration, work success, etc.). All these processes and emotions serve regulatory functions in narcissism and lead to the development of contingent self-esteem (Tracy et al., 2009). Although the concept of hubristic pride as a response to chronic excessive shame assumes that these emotions are characteristic for both types of narcissism, recent studies cast doubt on this assumption. Evidence supporting the structural split in the self-representational system – an unstable situation of implicit feelings of shame and inadequacy coexisting with explicit feelings of grandiosity – has so far been mixed (Bosson, this volume; Horvath & Morf, 2009), at least in the case of grandiose narcissisism. Krizan and Johar’s (2015) studies indicate that it is vulnerable, rather than grandiose, narcissism that is strongly associated with shame-proneness, again suggesting that grandiose narcissists are more “successful” in their self-regulatory efforts than their vulnerable counterparts (Campbell et al., 2004).

Envy and Anger

Envy is one of the most important emotions in the lives of vulnerable narcissists – they resent higher status peers and revel in the misfortune of others (Krizan & Johar, 2012; Nicholls & Stukas, 2011). Grandiose narcissism has a more complicated association and is thus less predictive of envy and schadenfreude (Krizan & Johar, 2012; Lange, Crusius, & Hagemeyer, 2016; Neufeld & Johnson, 2016; Porter, Bhanwer, Woodworth, & Black, 2014). Its leadership/authority component protects grandiose narcissists from dispositional envy (Neufeld & Johnson, 2016), while entitlement and antagonism, common to both grandiose and vulnerable forms of narcissism, predict malicious envy (Lange et al., 2016; Neufeld & Johnson, 2016; Porter et al., 2014). Considering that envy, just like shame, is a painful emotion that individuals try to avoid, grandiose narcissists again appear to more successfully navigate their emotional landscapes.

Anger, rage, and aggression have been the crux of many theoretical models of narcissism, starting from early psychoanalytic to contemporary ones from social-personality psychology (e.g., Alexander, 1938; Freud, 1932; Jacobson, 1964; Krizan & Johar, 2015; Saul, 1947). However, the routes that lead vulnerable and grandiose narcissists to aggression might not be the same, as envisioned in different theories. According to the “authentic versus hubristic” model of pride (Tracy & Robins, 2004, 2006), externalizing blame and experiencing anger might be a viable strategy for coping with chronic shame. Aggression is an appealing behavioral alternative to shamed individuals because it serves an ego-protective function and provides immediate relief from the pain of shame (Tangney & Dearing, 2002). Aggressive responses in both grandiose and vulnerable narcissists might therefore represent a “shame-rage” spiral (Lewis, 1971; Scheff, 1987; Tracy et al., 2011).

However, some researchers believe that this particular dynamic only refers to vulnerable narcissists as their grandiose counterparts do not typically hold negative self-opinions of any sort, including implicit or unconscious, and hence are not prone to shame (Campbell et al., 2004). Recent theoretical and empirical work on narcissistic rage suggests that it is indeed narcissistic vulnerability rather than grandiosity that is a key source of narcissistic rage, as its necessary conditions include vulnerable sense of self, an explosive mixture of shame, hostility, and extreme anger (Krizan & Johar, 2015). The resultant outburst of aggression is disproportionate, dysfunctional, and often misdirected.

Among grandiose narcissists, in contrast, aggression might rather be understood as an instrumental response to a threat to their position of dominance; it serves to directly defend and assert it and does not include the intermediary of shame (Campbell et al., 2004). Grandiose narcissists are prone to aggression when faced with strong direct threats to the self (such as public impeachments of one’s ability, intelligence, or social status), and their aggressive responses might rather be maneuvers aimed at restoring their superiority rather than outbursts of unrestrained, uncontrollable rage fuelled by shame and chronic anger (Barry et al., 2007; Fossati, Borroni, Eisenberg, & Maffei, 2010). This view is known as the threatened egotism model , and it assumes that acts of grandiose narcissists are motivated by inflated self-esteem and self-entitlement (Bushman & Baumeister, 1998; Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001; Stucke & Sporer, 2002). Narcissistically grandiose aggression might have a sadistic flavor. Altogether, grandiose narcissists’ aggressive responses to ego-threats are deliberate means of asserting superiority and dominance, rather than uncontrolled acts of rage characteristic of vulnerable narcissists (Krizan & Johar, 2015).

Emotion Regulation

As mentioned above, narcissistic self-esteem contingency and sensitivity to social comparison result in high affect volatility. There are both intra- and interpersonal causes of such volatility. Grandiose narcissists use other people to regulate their self-esteem, producing a typical dynamic of initial excitement, “seduction,” and later disappointment (Back et al., 2013; Campbell & Campbell, 2009; Czarna, Leifeld, Śmieja, Dufner, & Salovey, 2016; Leckelt, Küfner, Nestler, & Back, 2015; Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001; Paulhus, 1998). In vulnerable narcissism, hypersensitivity and disappointment stemming from unmet entitled expectations lead to social withdrawal and avoidance in a futile attempt to manage self-esteem. This brings about shame, depression, anger, and hostility and often culminates in outbursts of narcissistic rage (Dickinson & Pincus, 2003; Krizan & Johar, 2015). Altogether, narcissism, in both its forms, and with its self-esteem (dys) regulation, generates significant emotional instability (and interpersonal turmoil).

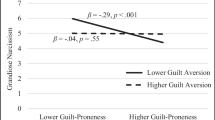

Difficulties in emotion regulation are more evident in vulnerable narcissism than in grandiose narcissism. For instance, Zhang, Wang, You, Lu, and Luo (2015) found that grandiose narcissism was negatively correlated with difficulties in emotion regulation, whereas vulnerable narcissism was substantially positively correlated with multiple indices of maladaptive emotion regulation, such as nonacceptance of one’s own emotional responses, impulse control difficulties, limited access to emotion regulation strategies, and a lack of emotional clarity. Another study indicated different gender-specific mediating paths via deficits within components of emotional intelligence that underlie the relationship between vulnerable narcissism and hostility (Zajenkowski, Czarna, Szymaniak, & Maciantowicz, in preparation). Specifically, it was found that emotion management mediates the relationship between vulnerable narcissism and hostility among men, whereas for women emotion facilitation acts as a mediator of the narcissism – hostility association.

Grandiose narcissism entails both costs and benefits in terms of emotion regulation. Even though in many studies grandiose narcissists have displayed substantial volatility in response to failure (e.g., Rhodewalt & Morf, 1998), there is evidence that they are also capable of high task persistence when no alternative paths to self-enhancement are available. In comparison to people low in grandiose narcissism, they report more positive emotions and resiliency in the face of failure (when no comparative feedback with competitors is provided; Wallace, Ready, & Weitenhagen, 2009). The fact that grandiose narcissists can maintain confidence and tolerate setbacks in pursuit of a goal but may quickly withdraw from challenging tasks if given an easier path to success actually suggests good self-regulation. Their resilience to stress might, nevertheless, be illusory. Multiple studies indicate that even if narcissistic individuals deny that they are influenced by stress, grandiose narcissism comes with certain physiological cost, namely, increased reactivity to emotional distress, manifested in elevated output of stress-related biomarkers, and this seems particularly true for men. These physiological costs are detectable on hormonal, cardiovascular, and neurological levels (Cheng, Tracy, & Miller, 2013; Edelstein, Yim, & Quas, 2010; Kelsey, Ornduff, McCann, & Reiff, 2001; Reinhard, Konrath, Lopez, & Cameron, 2012; Sommer et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2015).

Some recent studies aimed to discover specific mechanisms underlying emotion regulation and emotion processing in narcissism. One of the studies focused on fading affect bias (FAB, the effect of differential affective fading associated with autobiographical memories such that positive affect fades slower than negative affect). The results showed that grandiose narcissists evince a FAB when they recall achievement-themed (agentic) autobiographical events and that they tend to show a reversed FAB (their positive affect fades faster than their negative affect) when they recall communal-themed events (Ritchie, Walker, Marsh, Hart, & Skowronski, 2015). Since FAB is an adaptive phenomenon representing effective emotion regulation, these findings reveal a disruption of emotion regulation in high grandiose narcissists. While grandiose narcissists excessively retain the positive affect associated with individual achievement and other agency-themed events, they also tend to deflect positive communal, cooperative experiences and memories and retain negative affect of life events involving interactions with other individuals. This mechanism might reinforce narcissists’ grandiose agentic self-construal.

Czarna, Wróbel, Dufner, and Zeigler-Hill (2015) examined grandiose narcissists’ susceptibility to emotional contagion , that is, the transfer of emotional states from one person to another. Given that narcissists have a strong self-focus and a tendency toward self-absorption (Campbell & Miller, 2011), it seemed likely that they would pay less attention to the emotional states of other people. Two studies with experimentally induced affect showed that grandiose narcissists were less prone to emotional contagion than individuals low in grandiose narcissism (Czarna et al., 2015). Hence, grandiose narcissists were less likely to “catch the emotions” of others, a result corroborating their generally low empathy.

These results raise the question of what exactly underlies the effects. Are narcissists incapable or unwilling to engage in other people’s emotional states? Or perhaps both? So far, there is consistent evidence suggesting an important role of lacking motivation among grandiose narcissists for understanding others’ emotional states and needs (e.g., Aradhye & Vonk, 2014; Czarna, Czerniak, & Szmajke, 2014; Hepper, Hart, & Sedikides, 2014; Italiano, 2017). There is also mixed evidence regarding grandiose narcissists’ ability to accurately recognize and process emotion-related information. Some studies report deficits and biases (lower emotion recognition accuracy with response bias in patients with narcissistic personality disorder, Marissen, Deen, & Franken, 2012, and in high trait grandiose narcissism, Tardif, Fiset, & Blais, 2014, and discordant emotional reactions to expressions of emotions in high grandiose narcissism, Wai & Tiliopoulos, 2012), while others report intact or even superior abilities (Konrath, Corneille, Bushman, & Luminet, 2014; Ritter et al., 2011). Research concerning the corresponding abilities and motivation in trait vulnerable narcissism has been scarce with some evidence indicating lower perspective taking skills among vulnerable narcissists (Aradhye & Vonk, 2014).

In conclusion, while vulnerable narcissists undoubtedly have multiple deficits in emotion regulation, it has been unclear whether this is also true for grandiose narcissists . So far a number of “specificities” (or perhaps “anomalies”) have been discovered in emotion regulation of the latter. That is, grandiose narcissists seem more impermeable to other people’s emotions than people lower in narcissism, and their affect related to autobiographical memories shows different dynamics depending on the content of the memories that is typical for low narcissists. Grandiose narcissists have little motivation to capture and understand other people’s emotions, but whether they also lack skills to do it or not remains an open question. There is some physiological evidence indicating that they respond strongly to emotional distress, even though they deny such responsiveness when explicitly asked.

Future Directions

Owing to the important contributions from clinical and social-personality researchers, knowledge has accumulated about the emotional life of narcissists. We have shown that the emotional lives differ quite remarkable for grandiose versus vulnerable narcissists, with grandiose narcissists appearing, on the whole, more like “successful narcissists” and vulnerable narcissists appearing more like “failed narcissists” (Back & Morf, 2018; Campbell et al., 2004).

Yet, it might be necessary to make even more fine-grained distinctions. Theoretical developments such as emergence of new models (e.g., the narcissistic admiration and rivalry concept – NARC, Back et al., 2013; the narcissism spectrum model, Krizan & Herlache, 2018) enable more detailed analyses. Research on NARC has shown that the admiration component of grandiose narcissism (which is indicating of assertative self-enhancement) is linked to positive emotionality, whereas the rivalry component of narcissism (which is indicative of antagonistic self-protection) is linked to negative emotionality (Back et al., 2013). Future research should take a more differentiated view at the emotions that are linked to the subcomponents of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. This way, a better understanding will be gained of the similarity and the differences between the two forms of narcissism.

Furthermore, more research should be dedicated to the question of whether deficient abilities or motivation accounts for narcissists’ low empathy. For instance, do narcissists show higher empathy or emotional contagion if it suits their ultimate goal to garner narcissistic supply (admiration, adoration)? Is their low sensitivity to other people’s emotional states a result of low motivation to attend to other people’s internal states or perhaps a high motivation to maintain and secure own positive mood through “impermeability” to others’ emotions? Do narcissists show deficits or biases in the ability to recognize emotions that could affect their reactions to others? Existing theories (e.g., Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001) provide a general conceptual outline of self-regulatory processes in narcissists, but a detailed coherent map of particular cognitive, perceptual, and emotional mechanisms underlying these processes is still to be drafted. More research on narcissists’ emotion regulation is warranted.

When studying narcissists’ emotionality, an important step forward would be to go beyond self-report measures. There is a wide variety of measurement methods, including physiological measures such as electromyography, and a wide range of stimuli of different complexity, starting from pictures and still photos and ending with dynamic stimuli that allow for exact timing and testing thresholds of emotion recognition, available to researchers. Also, virtual reality could be used in studies, enhancing participants’ immersion in experimental situations.

Finally, once accumulating evidence allows for a fuller understanding of how different aspects and mechanisms of narcissists’ self-regulatory systems function to produce the intra- or interpersonally problematic emotional expressions, we will hopefully be ready to propose effective interventions that will bring relief to narcissists themselves and their relationship partners.

References

Alexander, F. (1938). Remarks about the relation of inferiority feelings to guilt feelings. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 19, 41–49.

Aradhye, C., & Vonk, J. (2014). Theory of mind in grandiose and vulnerable facets of narcissism. In A. Besser (Ed.), Handbook of the psychology of narcissism: Diverse perspectives (pp. 347–363). New York: Nova Publishers.

Back, M., & Morf, C. C. (2018). Narcissism. In V. Zeigler-Hill, & T. K. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8 (ISBN: 978-3-319-28099-8 [Print] 978-3-319-28099-8 [Online]).

Back, M. D., Küfner, A. C., Dufner, M., Gerlach, T. M., Rauthmann, J. F., & Denissen, J. J. (2013). Narcissistic admiration and rivalry: Disentangling the bright and dark sides of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105, 1013–1037.

Barry, T. D., Thompson, A., Barry, C. T., Lochman, J. E., Adler, K., & Hill, K. (2007). The importance of narcissism in predicting proactive and reactive aggression in moderately to highly aggressive children. Aggressive Behavior, 33, 185–197.

Besser, A., & Priel, B. (2010). Grandiose narcissism versus vulnerable narcissism in threatening situations: Emotional reactions to achievement failure and interpersonal rejection. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29, 874–902.

Bogart, L. M., Benotsch, E. G., & Pavlovic, J. D. P. (2004). Feeling superior but threatened: The relation of narcissism to social comparison. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 26, 35–44.

Bushman, B. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (1998). Threatened egotism, narcissism, self-esteem, and direct and displaced aggression: Does self-love or self-hate lead to violence? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 219–229.

Campbell, K. W., & Foster, J. D. (2007). The narcissistic self: Background, an extended agency model, and ongoing controversies. In C. Sedikides & S. Spencer (Eds.), Frontiers in social psychology: The self (pp. 115–138). Philadelphia: Psychology Press.

Campbell, W. K., & Campbell, S. M. (2009). On the self-regulatory dynamics created by the peculiar benefits and costs of narcissism: A contextual reinforcement model and examination of leadership. Self and Identity, 8, 214–232.

Campbell, W. K., Foster, J. D., & Brunell, A. B. (2004). Running from shame or reveling in pride? Narcissism and the regulation of self-conscious emotions. Psychological Inquiry, 15, 150–153.

Campbell, W. K., & Miller, J. D. (2011). The handbook of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Cheng, J. T., Tracy, J. L., & Miller, G. E. (2013). Are narcissists hardy or vulnerable? The role of narcissism in the production of stress-related biomarkers in response to emotional distress. Emotion, 13, 1004–1011.

Czarna, A. Z., Czerniak, A., & Szmajke, A. (2014). Does communal context bring the worst in narcissists? Polish Psychological Bulletin, 45, 464–468.

Czarna, A. Z., Leifeld, P., Śmieja, M., Dufner, M., & Salovey, P. (2016). Do narcissism and emotional intelligence win us friends? Modeling dynamics of peer popularity using inferential network analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42, 1588–1599.

Czarna, A. Z., Wróbel, M., Dufner, M., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2015). Narcissism and emotional contagion do narcissists “catch” the emotions of others? Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6, 318–324.

Dickinson, K. A., & Pincus, A. L. (2003). Interpersonal analysis of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. Journal of Personality Disorders, 17, 188–207.

Diener, E., & Lucas, R. (1999). Personality and subjective well-being. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Dufner, M., Denissen, J. J. A., van Zalk, M., Matthes, B., Meeus, W. H. J., van Aken, M. A. G., et al. (2012). Positive intelligence illusions: On the relation between intellectual self-enhancement and psychological adjustment. Journal of Personality, 80, 537–571.

Dufner, M., Gebauer, J. E., Sedikides, C., & Denissen, J. J. A. (in press). Self-enhancement and psychological adjustment: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868318756467

Edelstein, R. S., Yim, I. S., & Quas, J. A. (2010). Narcissism predicts heightened cortisol reactivity to a psychosocial stressor in men. Journal of Research in Personality, 44, 565–572.

Elliot, A. J., & Thrash, T. M. (2002). Approach-avoidance motivation in personality: Approach and avoidance temperaments and goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 804–818.

Fossati, A., Borroni, S., Eisenberg, N., & Maffei, C. (2010). Relations of proactive and reactive dimensions of aggression to overt and covert narcissism in nonclinical adolescents. Aggressive Behavior, 36, 21–27.

Foster, J. D., & Trimm, R. F., IV. (2008). On being eager and uninhibited: Narcissism and approach-avoidance motivation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 1004–1017.

Freud, S. (1932). Libidinal types. The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 1, 3–6.

Geukes, K., Nestler, S., Hutteman, R., Dufner, M., Küfner, A. C., Egloff, B., et al. (2017). Puffed-up but shaky selves: State self-esteem level and variability in narcissists. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112, 769–786.

Hepper, E. G., Hart, C. M., & Sedikides, C. (2014). Moving Narcissus: Can narcissists be empathic? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40, 1079–1091.

Horvath, S., & Morf, C. C. (2009). Narcissistic defensiveness: Hypervigilance and avoidance of worthlessness. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 1252–1258.

Italiano, A. (2017). What’s in it for me? Why narcissists help others. Unpublished honors thesis, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA.

Jacobson, E. (1964). The self and the object world. New York: International University Press.

Kelsey, R. M., Ornduff, S. R., McCann, C. M., & Reiff, S. (2001). Psychophysiological characteristics of narcissism during active and passive coping. Psychophysiology, 38, 292–303.

Kohut, H. (1971). The analysis of self. New York: International Universities Press.

Konrath, S., Corneille, O., Bushman, B. J., & Luminet, O. (2014). The relationship between narcissistic exploitativeness, dispositional empathy, and emotion recognition abilities. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 38, 129–143.

Krizan, Z., & Bushman, B. J. (2011). Better than my loved ones: Social comparison tendencies among narcissists. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 212–216.

Krizan, Z., & Herlache, A. D. (2018). The narcissism spectrum model: A synthetic view of narcissistic personality. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 22(1), 3–31

Krizan, Z., & Johar, O. (2012). Envy divides the two faces of narcissism. Journal of Personality, 80, 1415–1451.

Krizan, Z., & Johar, O. (2015). Narcissistic rage revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108, 784–801.

Lange, J., Crusius, J., & Hagemeyer, B. (2016). The evil queen’s dilemma: Linking narcissistic admiration and rivalry to benign and malicious envy. European Journal of Personality, 30, 168–188.

Leckelt, M., Küfner, A. C., Nestler, S., & Back, M. D. (2015). Behavioral processes underlying the decline of narcissists’ popularity over time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109, 856–871.

Lewis, H. B. (1971). Shame and guilt in neurosis. New York: International University Press.

Marissen, M. A., Deen, M. L., & Franken, I. H. (2012). Disturbed emotion recognition in patients with narcissistic personality disorder. Psychiatry Research, 198, 269–273.

Miller, J. D., Hoffman, B. J., Gaughan, E. T., Gentile, B., Maples, J., & Campbell, W. K. (2011). Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: A nomological network analysis. Journal of Personality, 79, 1013–1042.

Miller, J. D., Lynam, D. R., Vize, C., Crowe, M., Sleep, C., Maples-Keller, J. L., et al. (2017). Vulnerable narcissism is (mostly) a disorder of neuroticism. Journal of Personality, 86, 1467–1494.

Morf, C. C., & Rhodewalt, F. (2001). Unraveling the paradoxes of narcissism: A dynamic self-regulatory processing model. Psychological Inquiry, 12, 177–196.

Neufeld, D. C., & Johnson, E. A. (2016). Burning with envy? Dispositional and situational influences on envy in grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. Journal of Personality, 84, 685–696.

Nicholls, E., & Stukas, A. A. (2011). Narcissism and the self-evaluation maintenance model: Effects of social comparison threats on relationship closeness. The Journal of Social Psychology, 151, 201–212.

Paulhus, D. L. (1998). Interpersonal and intrapsychic adaptiveness of trait self-enhancement: A mixed blessing? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1197–1208.

Pincus, A. L., Ansell, E. B., Pimentel, C. A., Cain, N. M., Wright, A. G., & Levy, K. N. (2009). Initial construction and validation of the pathological narcissism inventory. Psychological Assessment, 21, 365–379.

Porter, S., Bhanwer, A., Woodworth, M., & Black, P. J. (2014). Soldiers of misfortune: An examination of the dark triad and the experience of schadenfreude. Personality and Individual Differences, 67, 64–68.

Reinhard, D. A., Konrath, S. H., Lopez, W. D., & Cameron, H. G. (2012). Expensive egos: Narcissistic males have higher cortisol. PLoS One, 7, e30858.

Rhodewalt, F., Madrian, J. C., & Cheney, S. (1998). Narcissism, self-knowledge organization, and emotional reactivity: The effect of daily experiences on self-esteem and affect. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24, 75–87.

Rhodewalt, F., & Morf, C. C. (1998). On self-aggrandizement and anger: A temporal analysis of narcissism and affective reactions to success and failure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 672–685.

Ritchie, T. D., Walker, W. R., Marsh, S., Hart, C., & Skowronski, J. J. (2015). Narcissism distorts the fading affect bias in autobiographical memory. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 29, 104–114.

Ritter, K., Dziobek, I., Preißler, S., Rüter, A., Vater, A., Fydrich, T., et al. (2011). Lack of empathy in patients with narcissistic personality disorder. Psychiatry Research, 187, 241–247.

Rose, P. (2002). The happy and unhappy faces of narcissism. Personality and Individual Differences, 33, 379–391.

Saul, L. (1947). Emotional maturity. Philadelphia: Lippincott.

Scheff, T. J. (1987). The shame-rage spiral: A case study of an interminable quarrel. In H. B. Lewis (Ed.), The role of shame in symptom formation (pp. 109–149). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Sedikides, C., Rudich, E. A., Gregg, A. P., Kumashiro, M., & Rusbult, C. (2004). Are normal narcissists psychologically healthy?: Self-esteem matters. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 400–416.

Sommer, K. L., Kirkland, K. L., Newman, S. R., Estrella, P., & Andreassi, J. L. (2009). Narcissism and cardiovascular reactivity to rejection imagery. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39, 1083–1115.

Stucke, T. S., & Sporer, S. L. (2002). When a grandiose self-image is threatened: Narcissism and self-concept clarity as predictors of negative emotions and aggression following ego-threat. Journal of Personality, 70, 509–532.

Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. L. (2002). Shame and guilt. New York: Guilford.

Tardif, J., Fiset, D., & Blais, C. (2014). Narcissistic personality differences in facial emotional expression categorization. Journal of Vision, 14, 1444.

Thomaes, S., Bushman, B. J., Stegge, H., & Olthof, T. (2008). Trumping shame by blasts of noise: Narcissism, self-esteem, shame, and aggression in young adolescents. Child Development, 79, 1792–1801.

Tracy, J. L., Cheng, J., Robins, R. W., & Trzesniewski, K. (2009). Authentic and hubristic pride: The affective core of self-esteem and narcissism. Self and Identity, 8, 196–213.

Tracy, J. L., Cheng, J. T., Martens, J. P., & Robins, R. W. (2011). The affective core of narcissism: Inflated by pride, deflated by shame. In W. K. Campbell & J. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder: Theoretical approaches, empirical findings, and treatments (pp. 330–343). New York: Wiley.

Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2004). Putting the self into self-conscious emotions: A theoretical model. Psychological Inquiry, 15, 103–125.

Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2006). Appraisal antecedents of shame and guilt: Support for a theoretical model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 1339–1351.

Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2007a). The nature of pride. In J. L. Tracy, R. W. Robins, & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research. New York: Guilford.

Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2007b). The psychological structure of pride: A tale of two facets. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 506–525.

Wai, M., & Tiliopoulos, N. (2012). The affective and cognitive empathic nature of the dark triad of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 794–799.

Wallace, H. M., Ready, C. B., & Weitenhagen, E. (2009). Narcissism and task persistence. Self and Identity, 8, 78–93.

Wink, P. (1991). Two faces of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 590–597.

Zajenkowski, M., & Czarna, A. Z. (2015). What makes narcissists unhappy? Subjectively assessed intelligence moderates the relationship between narcissism and psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 77, 50–54.

Zajenkowski, M., Czarna, A.Z., Szymaniak, K., Maciantowicz, O. (under review). Narcissism and the regulation of anger and hostility. Intermediary role of emotional intelligence. PloS One.

Zeigler-Hill, V., Myers, E. M., & Clark, C. B. (2010). Narcissism and self-esteem reactivity: The role of negative achievement events. Journal of Research in Personality, 44, 285–292.

Zhang, H., Wang, W., You, X., Lu, W., & Luo, Y. (2015). Associations between narcissism and emotion regulation difficulties: Respiratory sinus arrhythmia reactivity as a moderator. Biological Psychology, 110, 1–11.

Acknowledgments

The present work was supported by grant no. 2015/19/B/HS6/02214 from the National Science Center, Poland, awarded to the first author and by grant no. 2016/23/B/HS6/00312 from the National Science Center, Poland, to the second author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Czarna, A.Z., Zajenkowski, M., Dufner, M. (2018). How Does It Feel to Be a Narcissist? Narcissism and Emotions. In: Hermann, A., Brunell, A., Foster, J. (eds) Handbook of Trait Narcissism. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92171-6_27

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92171-6_27

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-92170-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-92171-6

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)