Abstract

This chapter draws upon the empirical literature to delineate the distinguishing characteristics of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder (NPD). We find that these constructs can be well described using models of general personality such as the five-factor model (FFM) and, in particular, three primary traits including (low) agreeableness (or antagonism, entitlement, and self-involvement), agentic extraversion (or boldness, behavioral approach orientation), and neuroticism (or reactivity, behavioral avoidance orientation). Our review led to three primary conclusions. First, the FFM trait correlates of NPD and grandiose narcissism overlap quite substantially. Second, the two differ to some degree with regard to the role of extraversion, with stronger relations found for grandiose narcissism than NPD. Third, extant data suggest that vulnerable narcissism represents a construct that is largely divergent from NPD and grandiose narcissism, composed of the tendency to experience a wide array of negative emotions such as depression, self-consciousness, stress, anxiety, and urgency. Nevertheless, vulnerable narcissism shares a common core of interpersonal antagonism, though the traits associated with grandiose and vulnerable narcissism are not identical. Finally, our chapter concludes with recommendations for aligning the alternative model of personality disorders (PDs) in Section III of DSM-5 with the substantial and long-standing empirical research literature that documents the improved validity of dimensional, trait-based models of PDs.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Grandiose narcissism

- Vulnerable narcissism

- Personality

- Five-factor model

- NPD

- NPD impairment

- FFNI

- Five-factor narcissism inventory

There is increasing recognition that there are at least two different dimensions or forms of narcissism (i.e., grandiose vs. vulnerable) that have been discussed using a variety of titles (e.g., Dickinson & Pincus, 2003; Miller & Campbell, 2008; Wink, 1991). Cain, Pincus, and Ansell (2008) provided a comprehensive list of the terms that have been associated with grandiose (e.g., manipulative, phallic, overt, egotistical, oblivious, exhibitionistic, psychopathic) and vulnerable narcissism (e.g., craving, contact-shunning, thin-skinned, hypervigilant, shy). In general, grandiose narcissism is associated with traits such as immodesty, interpersonal dominance, self-absorption, callousness, and manipulativeness; grandiose narcissism also tends to be positively related to self-esteem and negatively related to psychological distress. Alternatively, vulnerable narcissism is associated with increased rates of psychological distress and negative emotions (e.g., anxiety, shame), low self-esteem and feelings of inferiority, as well as egocentric and hostile interpersonal behaviors. Both, however, are thought to contain a core of antagonism (e.g., Miller, Lynam, Hyatt, & Campbell, 2017), although this is weaker in vulnerable narcissism than grandiose, at least according to how they are currently operationalized.

There remain questions as to how these grandiose and vulnerable narcissism dimensions fit into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5; APA, 2013)/DSM-IV (APA, 1994)-based construct of NPD. Factor analyses of NPD symptoms indicate that the DSM-IV NPD criteria set is either primarily (i.e., six of nine symptoms; Fossati et al., 2005) or entirely (Miller, Hoffman, Campbell, & Pilkonis, 2008) consistent with grandiose narcissism, although self-report measures can inadvertently vary in the dimension captured (e.g., Miller et al., 2014). Nonetheless, the DSM-IV/5 text associated with NPD includes content indicative of vulnerability and fragility, such as the following:

Vulnerability in self-esteem makes individuals with narcissistic personality disorder very sensitive to “injury” from criticism or defeat. Although they may not show it outwardly, criticism may haunt these individuals and may leave them feeling humiliated, degraded, hollow, and empty. (APA, 2000, p. 715)

Although the DSM-IV categorical model was retained in the DSM-5 as the primary diagnostic system, an alternative model of PDs was included in Section III in order to encourage further study. The alternative DSM-5 model of NPD similarly involves primarily grandiose elements (Criterion B trait facets: grandiosity, attention seeking), although the personality dysfunction required in Criterion A includes vulnerability (e.g., “excessive reference to others for self-definition and self-esteem regulation; exaggerated self-appraisal inflated or deflated, or vacillating between extremes; emotional regulation mirrors fluctuations in self-esteem”) (APA, 2013, p. 767).

The purpose of this chapter is to draw upon the theoretical and empirical literature to delineate the distinguishing characteristics of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, as well as NPD. To do so, we use the framework of the most prominent general and pathological personality trait model – the five-factor model (FFM; e.g., Costa & McCrea, 1992). Finally, we discuss the diagnostic model of NPD used in Section III of the DSM-5 in view of the empirical literature.

Trait-Based Understanding of Narcissism

Some of the most constructive tools for identifying distinguishing characteristics of vulnerable narcissism, grandiose narcissism, and NPD have been various structural models of “normal” or “general” personality such as the FFM, which are now instantiated in the DSM-5 to represent more pathological variants of these traits. Multiple studies have demonstrated that personality disorders can be conceptualized and assessed using models of general personality like the FFM (Lynam & Widiger, 2001; Miller, Lynam, Widiger, & Leukefeld, 2001; Miller, Reynolds, & Pilkonis, 2004). With respect to narcissism, we review previous expert ratings and meta-analyses in order to delineate the relations between these three narcissism dimensions and general models of personality as assessed by the FFM. The FFM is particularly well suited to this task as it provides a more comprehensive representation of traits related to straightforwardness/sincerity and modesty than other similar models of personality (i.e., Big Five; John, Donahue, & Kentle, 1991), which may meaningfully underestimate the relation between grandiose narcissism and an antagonistic interpersonal style (Miller & Maples, 2011; Miller et al., 2011).

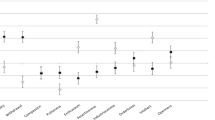

We have included tables of relevant relations between the FFM and narcissism dimensions to guide the reader (i.e., Tables 1.1 and 1.2). Tables include results from meta-analyses as well as expert, clinician, and lay ratings of relations between NPD, grandiose, and vulnerable narcissism. The relations between the FFM and NPD were based on meta-analytic reviews by Saulsman and Page (2004; FFM domains only) and Samuel and Widiger (2008; FFM domains and facets). The relations between the FFM and grandiose narcissism were based on the most recent, comprehensive meta-analysis from O’Boyle, Forsyth, Banks, Story, and White (2015; FFM domains and facets), while relations between the FFM and vulnerable narcissism were based on results from Campbell and Miller (2013). We also included academic ratings of NPD (Lynam & Widiger, 2001) and grandiose/vulnerable narcissism (Thomas, Wright, Lukowitsky, Donnellan, & Hopwood, 2012), clinician ratings of NPD (Samuel & Widiger, 2004), and lay ratings of prototypical cases of narcissism (i.e., subjects were asked to provide ratings of typical individuals “high in narcissism”; Miller, Lynam, Siedor, Crowe, & Campbell, 2018).

NPD

Expert raters – both academicians and clinicians – describe the prototypical individual with NPD as scoring very low on the FFM domain of agreeableness (antagonism; e.g., straightforwardness, modesty, altruism) and high on the agentic traits of extraversion (e.g., assertiveness, excitement seeking, activity) (Lynam & Widiger, 2001; Samuel & Widiger, 2004; see Table 1.1). Interestingly, lay rating of prototypical cases of narcissism (Miller et al., 2018) shows a very similar pattern suggesting that DSM-based conceptualizations are consistent with those held by the public more broadly in emphasizing traits related to antagonism and extraversion (Paulhus, 2001). Empirical examinations of the relations between FFM and NPD from meta-analytic reviews demonstrate a similar pattern of findings (FFM domains only, Saulsman & Page, 2004; FFM domains and facets, Samuel & Widiger, 2008). At the domain level, the largest effect size was for agreeableness (mean r = −0.34); none of the other domain-level effect sizes were larger than |0.15| (see Table 1.1). Nevertheless, while (low) agreeableness primarily underlies NPD, a facet-level analysis reveals heterogeneity in relations between NPD and the extraversion domain. Two meaningful contributions to NPD come from facets (i.e., assertiveness [r = 0.19] and excitement seeking [r = 0.16]) that reflect the agentic dimension of extraversion, while facets reflecting the communal dimension of extraversion (e.g., positive emotions, warmth) are less central to NPD.

Grandiose Narcissism

As noted above, lay raters have described the prototypical individual with narcissism as scoring low on the FFM domain of agreeableness and its facets of straightforwardness, altruism, compliance, modesty, tender-mindedness, and self-consciousness and high on the FFM facet of assertiveness (Miller et al., 2018; see Table 1.1). Thomas and colleagues also collected expert ratings of how FFM dimensions should correlate with grandiose narcissism; these raters predicted the largest effect sizes for agreeableness (negative) and extraversion (positive). The empirical relations between the FFM and grandiose narcissism have been meta-analytically synthesized by O’Boyle and colleagues (2015; see also Muris, Merckelbach, Otgaar, & Meijer, 2017; Vize et al., 2017). Grandiose narcissism manifested significant effect sizes with the domains of extraversion (mean r = 0.40) and agreeableness (mean r = −0.29), followed by a negative relation with neuroticism (mean r = −0.16) and a positive relation with openness (mean r = 0.20; see Table 1.1).Footnote 1

Vulnerable Narcissism

Expert ratings of the expected Big Five/FFM correlates of vulnerable narcissism collected by Thomas et al. (2012) highlighted the role of neuroticism (positive correlations), as well as extraversion and agreeableness (negative correlations). Campbell and Miller (2013) presented a meta-analytic review of the FFM correlates of vulnerable narcissism. At the domain level, vulnerable narcissism was strongly positively related to neuroticism (0.58) and negatively related to agreeableness (−0.35), extraversion (−0.27), and conscientiousness (−0.16; see Table 1.1).

Similarity of FFM Facet Level Correlations Across the Three Variants

We next examined the similarity of the FFM facet-level characterizations including both the expert/non-expert ratings and meta-analytic profiles. Because of the use of different metrics, we report simple correlations across the columns reported in Table 1.2 (rather than using an absolute similarity index like rICC that requires values to be on the same metric). The similarity scores for the three sets of faceted ratings demonstrate substantial consistency in how grandiose narcissism and NPD are conceptualized, irrespective of whether they were made by researchers, clinicians, or lay raters (rs ranged from 0.93 to 0.95). Importantly, these prototypicality ratings converge with the empirical trait profiles for DSM NPD and grandiose narcissism (rs ranged from 0.79 to 0.87). Vulnerable narcissism stands out as an outlier, however, as its empirical profile matches neither expert/lay ratings of NPD/narcissism nor the empirical profiles, although modest match was found for the match with the empirical profile for NPD (r = 0.41). Although not quantified due to the small number of correlates (5), it is clear, however, that the empirical profile for vulnerable narcissism maps closely on to the expert ratings provided by Thomas et al. (2012). Although measures of vulnerable narcissism yield empirical profiles that are substantially different than grandiose narcissism and NPD, they appear to capture the construct as currently operationalized by experts.

Comparing Grandiose Narcissism, Vulnerable Narcissism, and NPD: A Summary

A review of the strongest trait correlates of each narcissism construct leads to three primary conclusions. First, the trait correlates of NPD and grandiose narcissism overlap quite substantially. Both narcissism constructs are composed of traits related to a strongly antagonistic interpersonal style characterized by grandiosity, manipulativeness, deception, uncooperativeness, and anger. Second, the two differ to some degree, however, with regard to the role of extraversion with stronger relations found for grandiose narcissism than NPD. It is important to note that research suggests that extraversion might actually be parsed further into two components: agentic and communal positive emotionality/extraversion. Church (1994) described agentic positive emotionality as measuring “generalized social and work effectance,” whereas communal positive emotionality “emphasizes interpersonal connectedness” (p. 899). FFM facets that appeared to be commonly elevated in narcissism are those that are more closely associated with agentic positive emotionality (i.e., assertiveness, excitement seeking). Third, although research on the personality correlates of vulnerable narcissism has just begun, the extant data suggest that it represents a construct that is largely divergent from NPD and grandiose narcissism. From an FFM perspective, vulnerable narcissism is primarily composed of the tendency to experience a wide array of negative emotions such as depression, self-consciousness, stress, anxiety, and urgency, consistent with evidence that FFM neuroticism accounts for 65% of the variance in vulnerable narcissism scores (Miller et al., 2017). Furthermore, vulnerable individuals exhibit explicit low self-esteem , while grandiose individuals exhibit high explicit self-esteem most likely due to grandiose narcissism and self-esteem manifesting similar relations with extraversion and (low) neuroticism (Miller & Campbell, 2008; Miller et al., 2010; Pincus et al., 2009). However, although abundant empirical evidence indicates that neuroticism does not significantly underlie grandiose narcissism, one element of neuroticism may. Both grandiose and vulnerable share meaningful relations with FFM angry-hostility (r = 0.25 and 0.45, respectively). These relations are consistent with recent findings suggesting that even the most prototypically grandiose individuals exhibit anger for significant periods of time in response to ego threat (Hyatt et al., 2017). Longitudinal research is needed to elucidate the proximal and distal causes of anger that may differ across grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. For instance, research suggests that individuals with NPD symptoms respond to perceived dominance from others with increased quarrelsomeness (Wright et al., 2017).

As noted previously, the common core of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism appears to be interpersonal antagonism or (low) agreeableness from an FFM perspective Miller et al., 2018). However, even within this interpersonal domain, the traits associated with grandiose and vulnerable narcissism are not identical. Vulnerable individuals tend to be particularly low in interpersonal trust, even relative to grandiose individuals (see Table 1.1). Miller et al. (2010) have suggested that individuals high on vulnerable narcissism may manifest a hostile attribution bias such that they read malevolent intent in the actions of others and that these attributions may lead to more overtly problematic interpersonal behavior. In contrast, grandiosely narcissistic individuals tend to be particularly high in immodesty even relative to vulnerable individuals (see Table 1.1). Therefore, although individuals high on either narcissism dimension behave antagonistically, the motivation behind these behaviors may be quite different. For instance, the antagonism found among individuals elevated on vulnerable narcissism may be motivated by hostile attribution bias, whereas it may be motivated by needs for self-enhancement, status, and superiority among more grandiose individuals.

These opposing motives may also explain observed differential relations between grandiose/vulnerable narcissism and aggressive behavior. Grandiose and vulnerable individuals tend to both exhibit higher rates of reactive aggression, but grandiose individuals may uniquely exhibit proactive aggression, a more instrumental form of aggression that could be employed in the service of self-enhancement motives (Vize et al., 2017). Notably, however, at least one study suggests that vulnerable individuals, despite indicating higher levels of self-reported reactive aggression, do not exhibit higher levels of behavioral aggression or increased testosterone production in a laboratory-based behavioral aggression paradigm, while grandiose individuals do (Lobbestael, Baumeister, Fiebig, & Eckel, 2014). Thus, more research, especially that using behavioral paradigms, is needed to understand how grandiose and vulnerable narcissism similarly and differently relate to aggression.

In general, the trait profile associated with vulnerable narcissism appears to be more consistent with Borderline PD than NPD or grandiose narcissism. Miller et al. (2010) demonstrated that a vulnerable narcissism composite score manifested a nearly identical pattern of correlations (r = 0.93) with general personality traits (FFM), etiological variables (e.g., abuse, perceptions of parenting), and criterion variables (e.g., psychopathology, affect, externalizing behaviors) as did a Borderline PD composite. Consistent with this, the FFM facet profile of vulnerable narcissism is also more strongly correlated with the Lynam and Widiger (2001) expert profile for Borderline PD (r = 0.71) than with NPD (r = 0.06). Ultimately, vulnerable narcissism appears to share relatively little with the other two narcissism dimensions with the exception of an antagonistic interpersonal style and appears to have more in common with other pathological personality disorders such as Borderline PD.

State-Based Understanding of Narcissism

Some researchers posit that a purely trait-based conceptualization of narcissism leaves out important definitional features of narcissism (Pincus & Roche, 2011) and does not recognize intraindividual oscillation between vulnerable and grandiose personality states. Although vulnerable and grandiose dimensions of narcissism may be well differentiated in terms of stable traits, both are conceptualized by some researchers and clinical experts as stemming from a common etiology, namely, “intensely felt needs for validation and admiration,” which motivate the seeking out of self-enhancement experiences (grandiose) as well as “self-, emotion-, and behavioral dysregulation (vulnerable) when these needs go unfulfilled or ego threats arise” (p. 32; Kernberg, 2009; Pincus & Roche, 2011; Ronningstam, 2009). These researchers have argued that a purely trait-based conceptualization of narcissism, involving between-person typologies (e.g., grandiose vs. vulnerable), may understate the degree to which narcissism involves fluctuating patterns of personality states that oscillate within each individual (e.g., Pincus & Roche 2011).

Unfortunately, much more empirical research is needed to test these ideas as there are few data available that speak to this issue. In fact, existing data suggest that narcissism-related traits are relatively stable (Giacomin & Jordan, 2016). In fact, Wright and Simms (2016) found that core traits of narcissism like grandiosity were as stable across numerous assessments as many other pathological traits for which instability is not considered prototypic such as anxiousness and depressivity. Recent studies have suggested that grandiosely narcissistic individuals may experience some vulnerability, particularly the experience of anger following ego threat (Gore & Widiger, 2016; Hyatt et al., 2017), although there is little evidence to suggest that vulnerably narcissistic individuals experience periods of grandiosity. It is important to note, however, that both of these studies relied on prototypicality ratings of narcissism rather than longitudinal or ecological momentary assessment-based approaches (i.e., involving repeated measurement of participants’ current behaviors in real time) which are necessary for testing dynamic, oscillation-based hypotheses.

Narcissism and DSM-5

The inclusion of an alternative model for the conceptualization and diagnosis of personality disorders in Section III of DSM-5 (i.e., alternative DSM-5 model for personality disorders) marks an opportunity for aligning the diagnosis of PDs with the substantial and long-standing empirical research literature that documents the improved validity of dimensional, trait-based models of PDs. Although we believe this change represents an important and much-needed move toward the use of an empirically informed taxonomy, we believe there are a number of areas that can benefit from further attempts at refinement, particularly with regard to NPD. First, the use of only two traits to assess NPD as part of Criterion B (i.e., grandiosity, attention seeking) may provide inadequate coverage of the NPD construct. NPD is assessed with 50% fewer traits than the PD measured with the next fewest (4 – obsessive-compulsive, schizotypal) and less than 30% of some other PDs (e.g., 7, antisocial). Whether the limited number of traits articulated for NPD was due to its last-minute inclusion (NPD was slated for deletion until being reinstated; Miller, Widiger, & Campbell, 2010b) or concerns with discriminant validity with PDs such as antisocial, it is likely that additional traits would be helpful in capturing this construct. In fact, experts believe there are several other traits from the DSM-5 alternative PD trait model that are relevant to NPD including manipulativeness, callousness, risk taking, and hostility (Samuel & Widiger, 2008; Samuel, Lynam, Widiger, & Ball, 2012). If the latter is the case, we believe that the overall construct validity of NPD’s diagnosis must be prioritized over discriminant validity-related concerns and that NPD should be conceptualized in a rigorous and content-valid manner, even if the inclusion of these additional traits increases its overlap with near-neighbor disorders like antisocial PD (Miller et al., 2017). Such overlap is to be expected when one works from the perspective that all PDs represent configurations of some limited number of general/pathological traits (Lynam & Widiger, 2001).

Second, the alternative model of NPD as currently presented fails to adequately reflect a growing body of research that supports the addition of traits reflecting vulnerably narcissistic features (e.g., Miller & Campbell, 2008). Descriptions of these features have been found in numerous clinical accounts of the disorder (Cain et al., 2008) with increased empirical attention growing rapidly in the last 10–15 years (e.g., Miller et al., 2010b, 2011; Pincus et al., 2009). While there remains substantial ongoing debate as to the role of these vulnerable features in NPD (e.g., do all narcissistic individuals experience both grandiosity and vulnerability via a pattern of oscillation vs. many individuals fitting predominantly into a singular dimension (i.e., grandiose narcissism only; vulnerable narcissism only)), it is clear that the DSM-5 model should include some representation of vulnerability for cases where it is relevant.

Research to date demonstrates that while the two traits articulated in Criterion B do a fairly good job of accounting for variance in measures of grandiose narcissism (i.e., R2 = 63%), the same is not true for vulnerable narcissism (i.e., R2 = 19%; Miller, Gentile, Wilson, & Campbell, 2013). It is our contention that the core of narcissism/NPD are traits related to interpersonal antagonism and that traits from this domain should form the bedrock of its assessment in DSM. We believe the traits used should be expanded to include other relevant traits beyond grandiosity and attention seeking, particularly those emphasized by other expert-based characterizations (e.g., manipulativeness, callousness, entitlement; Ackerman, Hands, Donnellan, Hopwood, & Witt, 2016; Lynam & Widiger, 2001; Samuel et al., 2012) and indicated by FFM-NPD relations (e.g., manipulativeness, hostility, deceitfulness, callousness; Samuel & Widiger, 2008) and by recent work demonstrating that certain emotionally reactive personality traits are found in prototypically grandiose individuals (e.g., hostility; Gore & Widiger, 2016; Hyatt et al., 2017).

Next, we would include specifiers that would allow for the delineation of more grandiose (e.g., attention seeking, domineering) and vulnerable forms of narcissism (e.g., depressivity, anxiousness, separation anxiety). The flexibility of this trait-based approach is ideal for allowing many different representations of narcissism, beyond the two that have been the focus of substantial discussion and study in the literature. For instance, it is easy to imagine the clinical relevance of cases where narcissistic traits (e.g., grandiosity, callousness) are paired with traits from the domain of psychoticism (e.g., unusual beliefs, eccentricity).

Third, the alternative model’s assessment of impairment can be improved upon in at least two ways. Growing evidence suggests that impairment, as currently operationalized, may not contribute further information beyond traits (Bastiaansen et al., 2016; Few et al., 2013; Sleep, Wygant, & Miller, 2017), suggesting that greater incremental validity and clinical utility might be had by replacing Criterion A with a set of criteria that overlaps less substantially with the underlying traits. We believe these criteria should be more directly tied to functioning in specific domains (e.g., work and love) but also be widened in its purview to include impairment caused to others, which is particularly relevant to constructs like NPD (Miller, Campbell, & Pilkonis, 2007; Pilkonis, Hallquist, Morse, & Stepp, 2011). In addition, we believe the ordering which the Criteria A (impairment) and B (pathological traits) are assessed should be reversed, such that impairment is assessed only after one has determined whether there is the presence of pathological traits (e.g., Widiger, Costa, & McCrae, 2002). This ordering is both more logically coherent and should increase efficiency.

Future Directions

The time has come to clarify and consolidate a myriad of varied yet overlapping conceptualizations/models of narcissism, especially since many of the conceptualizations of narcissism converge in important ways. Regardless of whether one is describing NPD, grandiose, or vulnerable dimensions of narcissism, a comprehensive empirical literature demonstrates that narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder are well described by models of general personality and, in particular, three primary traits including (low) agreeableness (or antagonism, entitlement, and self-involvement), agentic extraversion (or boldness, behavioral approach-orientation), and neuroticism (or reactivity, behavioral avoidance-orientation). Such a three-factor model is already instantiated in the five-factor narcissism inventory (FFNI; Glover, Miller et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2016) and has been proposed recently as a necessary evolution in the field’s conceptualization of narcissism (e.g., unified trait model, Miller et al., 2017; narcissism spectrum model (NSM), Krizan & Herlache, 2018). This three-factor model is better able to account for the many different presentations of narcissism that go beyond the grandiose vs. vulnerable distinction that has been the focus of research for the past decade. For instance, research has generally shown a bifurcation in how grandiose (positively) and vulnerable narcissism (negatively) relate to self-esteem. However, a three-factor model shows that further differentiation is necessary and helpful such that the core of narcissism – antagonism – is unrelated to self-esteem, while the extraverted/agentic component is positively related and the vulnerable/neurotic component is negatively related. This three-factor model, which has close ties to three of the five major domains of personality, provides a framework for examining the mechanisms that underlie narcissism’s relations with both maladaptive and adaptive functioning. Ultimately, we believe that the field is now well situated to unify scholarly perspectives on narcissism into a singular integrative model.

Notes

- 1.

Important to note that Big Five-based assessments tend to manifest smaller relations between narcissism and agreeableness due to the exclusion of content related to honesty-humility, which is found to a much greater degree in FFM-based measures (e.g., NEO PI-R).

References

Ackerman, R. A., Hands, A. J., Donnellan, M. B., Hopwood, C. J., & Witt, E. A. (2016). Experts’ views regarding the conceptualization of narcissism. Journal of Personality Disorders, 31, 1–16.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text revision). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Bastiaansen, L., Hopwood, C. J., Van den Broeck, J., Rossi, G., Schotte, C., & De Fruyt, F. (2016). The twofold diagnosis of personality disorder: How do personality dysfunction and pathological traits increment each other at successive levels of the trait hierarchy? Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 7, 280–292.

Cain, N. M., Pincus, A. L., & Ansell, E. B. (2008). Narcissism at the crossroads: Phenotypic description of pathological narcissism across clinical theory, social/personality psychology, and psychiatric diagnosis. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 638–656.

Campbell, W. K., & Miller, J. D. (2013). Narcissistic personality disorder and the five-factor model: Delineating narcissistic personality disorder, grandiose narcissism, and vulnerable narcissism. In T. A. Widiger, P. J. Costa, T. A. Widiger, P. J. Costa (Eds.), Personality disorders and the five-factor model of personality (pp. 133–145). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.

Church, A. T. (1994). Relating the Tellegen and five-factor models of personality structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 898–909.

Costa, P. T., & McCrea, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO personality inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO five-factor inventory (NEO-FFI professional manual). Lutz, FL: PAR.

Dickinson, K. A., & Pincus, A. L. (2003). Interpersonal analysis of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. Journal of Personality Disorders, 17, 188–207.

Few, L. R., Miller, J. D., Rothbaum, A. O., Meller, S., Maples, J., Terry, D. P., et al. (2013). Examination of the section III DSM-5 diagnostic system for personality disorders in an outpatient clinical sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122, 1057–1069.

Fossati, A., Beauchaine, T. P., Grazioli, F., Carretta, I., Cortinovis, F., & Maffei, C. (2005). A latent structure analysis of diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, narcissistic personality disorder criteria. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 46, 361–367.

Giacomin, M., & Jordan, C. H. (2016). Self-focused and feeling fine: Assessing state narcissism and its relation to well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 63, 12–21.

Glover, N., Miller, J. D., Lynam, D. R., Crego, C., & Widiger, T. A. (2012). The Five-Factor Narcissism Inventory: A five-factor measure of narcissistic personality traits. Journal of Personality Assessment, 94, 500–512.

Gore, W. L., & Widiger, T. A. (2016). Fluctuation between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 7, 363–371.

Hyatt, C. S., Sleep, C. E., Lynam, D. R., Widiger, T. A., Campbell, W. K., Miller, J. D. (2017). Ratings of affective and interpersonal tendencies differ for grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: A replication and extension of Gore & Widiger. Journal of Personality. 86, 422–434.

John, O. P., Donahue, E. M., & Kentle, R. L. (1991). The big five inventory—versions 4a and 54. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research.

Kernberg, O. F. (2009). Narcissistic personality disorders: Part 1. Psychiatric Annals, 39, 105–166.

Krizan, Z., & Herlache, A. D. (2018). The narcissism spectrum model: A synthetic view of narcissistic personality. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 22, 3–31.

Lobbestael, J., Baumeister, R. F., Fiebig, T., & Eckel, L. A. (2014). The role of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism in self-reported and laboratory aggression and testosterone reactivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 69, 22–27.

Lynam, D. R., & Widiger, T. A. (2001). Using the five-factor model to represent the DSM-IV personality disorders: An expert consensus approach. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 401.

Miller, J. D., & Campbell, W. K. (2008). Comparing clinical and social-personality conceptualizations of narcissism. Journal of Personality, 76, 449–476.

Miller, J. D., Campbell, W. K., & Pilkonis, P. A. (2007). Narcissistic personality disorder: Relations with distress and functional impairment. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 48, 170–177.

Miller, J. D., Dir, A., Gentile, B., Wilson, L., Pryor, L. R., & Campbell, W. K. (2010). Searching for a vulnerable dark triad: Comparing factor 2 psychopathy, vulnerable narcissism, and borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality, 78, 1529–1564.

Miller, J. D., Gentile, B., Wilson, L., & Campbell, W. K. (2013). Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism and the DSM–5 pathological personality trait model. Journal of Personality Assessment, 95, 284–290.

Miller, J. D., Hoffman, B. J., Campbell, W. K., & Pilkonis, P. A. (2008). An examination of the factor structure of diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, narcissistic personality disorder criteria: One or two factors? Comprehensive Psychiatry, 49, 141–145.

Miller, J. D., Hoffman, B. J., Gaughan, E. T., Gentile, B., Maples, J., & Campbell, W. K. (2011). Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: A nomological network analysis. Journal of Personality, 79, 1013–1042.

Miller, J. D., Lynam, D. R., Hyatt, C. S., & Campbell, W. K. (2017). Controversies in narcissism. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13, 1–25.

Miller, J. D., Lynam, D. R., McCain, J. L., Few, L. R., Crego, C., Widiger, T. A., et al. (2016). Thinking structurally about narcissism: An examination of the five-factor narcissism inventory and its components. Journal of Personality Disorders, 30, 1–18.

Miller, J. D., Lynam, D. R., Siedor, L., Crowe, M., Campbell, W. K. (2018). Consensual lay profiles of narcissism and their connection to the five-factor narcissism inventory. Psychological Assessment 30, 10–18.

Miller, J. D., Lynam, D. R., Vize, C., Crowe, M., Sleep, C., Maples-Keller, J. L., et al. (2017). Vulnerable narcissism is (mostly) a disorder of neuroticism. Journal of Personality. 86, 186–199.

Miller, J. D., Lynam, D. R., Widiger, T. A., & Leukefeld, C. (2001). Personality disorders as extreme variants of common personality dimensions: Can the five factor model adequately represent psychopathy? Journal of Personality, 69, 253–276.

Miller, J. D., & Maples, J. (2011). Trait personality models of narcissistic personality disorder, grandiose narcissism, and vulnerable narcissism. In W. K. Campbell & J. D. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder: Theoretical approaches, empirical findings, and treatments (pp. 71–88). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Miller, J. D., McCain, J., Lynam, D. R., Few, L. R., Gentile, B., MacKillop, J., & Campbell, W. K. (2014). A comparison of the criterion validity of popular measures of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder via the use of expert ratings. Psychological Assessment, 26, 958–969.

Miller, J. D., Reynolds, S. K., & Pilkonis, P. A. (2004). The validity of the five-factor model prototypes for personality disorders in two clinical samples. Psychological Assessment, 16, 310–322.

Miller, J. D., Widiger, T. A., & Campbell, W. K. (2010b). Narcissistic personality disorder and the DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119, 640.

Muris, P., Merckelbach, H., Otgaar, H., & Meijer, E. (2017). The malevolent side of human nature: A meta-analysis and critical review of the literature on the dark triad (narcissism, machiavellianism, and psychopathy). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12, 183–204.

O’Boyle, E. H., Forsyth, D. R., Banks, G. C., Story, P. A., & White, C. D. (2015). A meta-analytic test of redundancy and relative importance of the dark triad and five-factor model of personality. Journal of Personality, 83, 644–664.

Paulhus, D. L. (2001). Normal narcissism: Two minimalist views. Psychological Inquiry, 12, 228–230.

Pilkonis, P. A., Hallquist, M. N., Morse, J. Q., & Stepp, S. D. (2011). Striking the (im)proper balance between scientific advances and clinical utility: Commentary on the DSM–5 proposal for personality disorders. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 2, 68–82.

Pincus, A. L., Ansell, E. B., Pimentel, C. A., Cain, N. M., Wright, A. G., & Levy, K. N. (2009). Initial construction and validation of the pathological narcissism inventory. Psychological Assessment, 21, 365–379.

Pincus, A. L., & Roche, M. J. (2011). Narcissistic grandiosity and narcissistic vulnerability. In W. K. Campbell & J. D. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder: Theoretical approaches, empirical findings, and treatments (pp. 31–40). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Ronningstam, E. (2009). Facing DSM-V. Psychiatric Annals, 39, 111–121.

Samuel, D. B., Lynam, D. R., Widiger, T. A., & Ball, S. A. (2012). An expert consensus approach to relating the proposed DSM-5 types and traits. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 3, 1–16.

Samuel, D. B., & Widiger, T. A. (2004). Clinicians’ personality descriptions of prototypic personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 18, 286–308.

Samuel, D. B., & Widiger, T. A. (2008). A meta-analytic review of the relationships between the five-factor model and DSM-IV-TR personality disorders: A facet level analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 1326–1342.

Saulsman, L. M., & Page, A. C. (2004). The five-factor model and personality disorder empirical literature: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 23, 1055–1085.

Sleep, C. E., Wygant, D. B., & Miller, J. D. (2017). Examining the incremental utility of DSM-5 section III traits and impairment in relation to traditional personality disorder scores in a female correctional sample. Journal of Personality Disorders 1–15.

Thomas, K. M., Wright, A. G., Lukowitsky, M. R., Donnellan, M. B., & Hopwood, C. J. (2012). Evidence for the criterion validity and clinical utility of the pathological narcissism inventory. Assessment, 19, 135–145.

Vize, C. E., Collison, K. L., Crowe, M. L., Campbell, W. K., Miller, J. D., Lynam, D. R. (2017). Using dominance analysis to decompose narcissism and its relation to aggression and externalizing outcomes. Assessment. 1–11.

Widiger, T. A., Costa, P. J., & McCrae, R. R. (2002). A proposal for Axis II: Diagnosing personality disorders using the five-factor model. In P. J. Costa, T. A. Widiger, P. J. Costa, T. A. Widiger (Eds.), Personality disorders and the five-factor model of personality (pp. 431–456). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.

Wink, P. (1991). Two faces of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 590–597.

Wright, A. G., & Simms, L. J. (2016). Stability and fluctuation of personality disorder features in daily life. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125, 641–656.

Wright, A. G. C., Stepp, S. D., Scott, L., Hallquist, M., Beeney, J. E., Lazarus, S. A., Pilkonis, P. A. (2017). The effect of pathological narcissism on interpersonal and affective processes in social interactions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 126, 898–910.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Weiss, B., Miller, J.D. (2018). Distinguishing Between Grandiose Narcissism, Vulnerable Narcissism, and Narcissistic Personality Disorder. In: Hermann, A., Brunell, A., Foster, J. (eds) Handbook of Trait Narcissism. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92171-6_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92171-6_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-92170-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-92171-6

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)