Abstract

Bipolar disorder (BD) and borderline personality disorder (BPD) are two disabling psychiatric conditions that are associated with a high rate of comorbidity and mortality (approximately 10% of BPD patients suffer from BD I disorder and another 10% show a comorbid BD II disorder). Up to date, the relationship between BD and BPD is controversial, and the debate on whether or not BPD should be considered within a broader bipolar spectrum is still ongoing. According to the literature, the underestimation of comorbidity rates between these disorders could lead to a significant delay in diagnosis and planning of appropriate treatments. In addition, this would lead to an increased risk of exposure to improper medications, a poorer outcome and a higher risk of complications. In this chapter we present a clinical case of a patient who suffers from BD and BPD. The discussion of this case report draws attention to the challenges associated with the diagnosis and treatment of a wide population of psychiatric patients, whose symptoms and clinical history appear to be somehow overlapping between BD and BPD, considered as distinct disorders according to the current nosography.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

5.1 Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a disabling mood disorder with a chronic recurrent course, associated with a high rate of comorbidity and mortality [1]. It is characterized by unusual shifts in mood, energy, activity levels, and in the ability to carry out day-to-day tasks. According to DSM-5, the diagnosis of BD type I disorder requires criteria for a manic episode to be met, while for BD type II disorder, criteria for a hypomanic episode and a major depressive episode should be fulfilled.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD), with a lifetime prevalence of around 3% [2], is one of the most frequently diagnosed personality disorders, affecting up to 20% of all psychiatric inpatients and thus representing a relevant socioeconomic burden [3]. A personality disorder is characterized by an enduring and inflexible pattern of behavior, thoughts, and feelings that seriously affect the person’s psychosocial functioning. Regarding BPD, its DSM-5 diagnostic criteria include a “significant impairment in self (identity or self-direction) and interpersonal functioning (empathy or intimacy)” as well as pathological personality traits in the following domains: negative affectivity (emotional lability, anxiousness, separation insecurity, depressivity), disinhibition (impulsivity and risk taking), and antagonism (hostility).

To date, the relationship between BD and BPD is controversial. The debate on whether or not BPD should be inscribed within the bipolar spectrum (hypomania, cyclothymia, switching on antidepressants, atypical depression and mixed states) is still ongoing, drawing heterogeneous conclusions. In fact, some authors raise the question on whether BPD should be considered an affective disorder or a personality disorder [4, 5]. For instance, Akiskal and his group included BPD within the bipolar spectrum. If considered—on the contrary—as separate disorders, the differential diagnosis, especially in the case of BD II, may not be straightforward. Discriminating between BD and BPD is often complicated [6, 7], but becomes crucial, especially in order to evaluate the comorbidity rates between the two disorders [8], as their co-occurrence significantly affects patients’ outcome.

The growing interest in this topic may be explained by the high comorbidity rates of these two conditions. For instance, it has been estimated that approximately 10% of BPD patients also suffer from BD I disorder and another 10% show a comorbid BD II disorder. Nevertheless, in the vast majority of cases (80–90%), each disorder is diagnosed in the absence of the other. Among BP II patients, 20% received a diagnosis of BPD, whereas it is only 10% among BD I patients [8]. According to NESARC (National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions) data, the lifetime prevalence of BPD is 29% among BD I patients and 24% among BD II ones. A recent meta-analysis by Fornaro and colleagues pointed out a 21.6% prevalence rate of BPD among 5273 BD subjects [9]. They established that 18.5% of people with BPD have a comorbid BD diagnosis and, interestingly, they found higher rates of comorbid BPD in BD II participants (37.7%) and in North American studies (26.2%). They also documented that male gender and increasing age are predictors of a lower prevalence of comorbid BPD in BD patients. This is in line with previous data reporting higher rates of female patients and younger mean age at onset in comorbid BD and BPD cases vs. BD samples without comorbid BPD [10, 11].

Some clinical factors are relevant when considering the comorbidity between BPD and BD (see Box 5.1). First of all, it is worth noting that BD patients with BPD have an earlier age at BD onset [10, 12,13,14,15] and, consequently, a longer duration of bipolar illness. Furthermore, they show higher suicidality rates compared with BD alone [15,16,17,18,19,20]. Interestingly, among BPD criteria, only impulsivity and unstable relationships were found to independently predict a past history of attempted suicide [21]. The enhanced suicidal risk associated with BPD was reported to be due to features either shared (impulsivity) or not shared (intense/unstable interpersonal relationship) with severe mood disorders [21]. Increased suicide risk was found only among females and among subjects with a genetic risk for suicide [22, 23], being also associated with high-lethality suicidal behavior [24, 25]. McDermid and coworkers reported a more frequent history of childhood trauma in BD with BPD compared to those without BPD [10]. Moreover, BD with comorbid BPD shows a higher rate of other comorbid psychiatric disorders, in particular a greater prevalence of substance abuse [10, 14, 15, 19, 26,27,28]. Regarding the clinical course, DB with BPD is related to an increased number of mood episodes over time and more major depressive episodes [10].

Box 5.1 Characteristics of BD in Comorbidity with BPD

-

Earlier age of BD onset

-

Higher suicidality rates and high-lethality suicidal behavior

-

History of childhood trauma

-

Higher rates of other comorbid psychiatric disorders

-

Higher prevalence of substance abuse

-

Increased number of mood episodes

-

Increased number of major depressive episodes

The two disorders share some core symptoms, such as affective instability and impulsivity. Affective instability is defined by DSM-5 as “a marked reactivity of mood (e.g., intense episodic dysphoria, irritability or anxiety, usually lasting a few hours and only rarely more than a few days)”. It represents a DSM-5 criterion for BPD, but not for BD, although being commonly observed also among these patients [29]. This is especially true when considering currently depressed BD type II cases [30], soft bipolar atypical forms of depressions [31], “ultrarapid” [32] and “stably unstable” bipolar cases [33]. It has also been proposed to include within the bipolar spectrum most of the forms of affective instability [34]. Impulsivity is another central feature of BPD, closely linked to mood lability. It is often seen as sexual impulsivity in both BPD and BD, although it can also be physical, aggressive, financial [7], or binge eating-related [35, 36]. Nevertheless, impulsivity in DB patients is more episodic, while in BPD it is more pervasive [37] (see Table 5.1).

Taken all together, it is clear that the underestimation of BD comorbidity rates in BPD cases could lead to a significant delay in diagnosis and planning of an appropriate treatment. In addition, this would lead to an increased risk of exposure to improper medications, a poorer outcome, and a higher risk of complications.

5.2 Case Presentation

Mrs. C., a 29-year-old woman, first came to our clinical attention in 2015, when she was admitted to the Psychiatry Department for depressive symptoms in BPD, including depressed mood, anhedonia, anergy, sleep disturbance, suicidal thoughts, and hyporexia. These symptoms worsened in 3 weeks prior to the visit, being responsible for a significant functional impairment.

For instance, in the examination room, she reported that her mood was low, she no longer enjoyed social gatherings and spent most of the day lying in her bed, with a significant tiredness and hopelessness. When asked about suicidal thoughts, she first denied, but she then confessed to have been thinking about hurting herself, so that “people would understand her suffering.” She lost 3 kg in the previous 3 weeks from hyporexia.

From the physical point of view, she did not report any particular disease and she did not take any regular medication. In relation to past psychiatric history, she reported three past episodes similar to the present one, but affirmed that she usually feels “sad and empty”. She reported one previous hospitalization for depression. She confessed to having recurrent self-mutilating behaviors, consisting in superficial cutting of the forearms. When asked about manic or hypomanic symptoms, she could recognize two distinct periods, which lasted approximately 1 month, characterized by grandiosity, reduced need for sleep, increased goal-directed activities, and excessive involvement in dangerous situations. She tried many different antidepressants, with only partial benefits, as they made her irritable and interfered with her sleep.

Considering the abovementioned symptomatology and the high risk of self-injurious behaviors, she was then hospitalized in our Psychiatric Department. During hospitalization, in order to perform an appropriate differential diagnosis, blood (general routine and thyroid function) and urine (drug screening) exams were performed, showing no significant alterations. She underwent the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS), which did not show any significant alterations (see Table 5.2). A cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) were also collected and did not report any alteration (see Figs. 5.1 and 5.2).

Furthermore, she underwent a clinical assessment, based on the administration of structured diagnostic interviews (SCID-I and SCID-II) and psychometric scales. She fulfilled criteria for:

-

Bipolar disorder type II, current depressive episode

-

Borderline personality disorder

-

Episodic alcohol abuse

-

Anorexia nervosa, with purging behavior

Criteria for BD II and BPD are presented in Boxes 5.2 and 5.3, respectively.

Box 5.2 DSM-5 Criteria for BD II

-

Criteria have been met for at least one hypomanic episode and at least one major depressive episode.

-

There has never been a manic episode.

-

The occurrence of the hypomanic episode(s) and major depressive episode(s) is not better explained by schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder, or other specified or unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders.

-

The symptoms of depression or the unpredictability caused by frequent alteration between periods of depression and hypomania causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

Box 5.3 DSM-5 Criteria for BPD

A pervasive pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affects and marked impulsivity beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts, as indicated by >5 (five) of the following:

-

1.

Frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment.

-

2.

A pattern of unstable and intense interpersonal relationships characterized by alternating between extremes of idealization and devaluation.

-

3.

Identity disturbance: markedly and persistently unstable self-image or sense of self.

-

4.

Impulsivity in at least two areas that are potentially self-damaging (e.g., excessive spending, substances of abuse, sex, reckless driving, binge eating). Note: Do not include suicidal or self-mutilating behavior covered in Criterion 5.

-

5.

Recurrent suicidal behavior, gestures, or threats, or self-mutilating behavior.

-

6.

Affective instability due to a marked reactivity of mood (e.g., intense episodic dysphoria, irritability, or anxiety usually lasting a few hours and only rarely more than a few days).

-

7.

Chronic feelings of emptiness.

-

8.

Inappropriate, intense anger, or difficulty controlling anger (e.g., frequent displays of temper tantrums, constant anger, and recurring fights).

-

9.

Transient, stress-related paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms.

The patient was discharged after 3 weeks on a pharmacological treatment with aripiprazole, lamotrigine, vortioxetine, and quetiapine, and addressed to our day hospital service for clinical stabilization.

Clinical History

-

Family history for suicide (maternal grandfather) and generalized anxiety disorder (mother)

-

No history of complications of pregnancy or delivery

-

No history of neurodevelopmental disorders

-

Good scholar and social functioning

-

No other medical conditions

The patient reported that her symptoms first appeared at the age of 12. At that time, her parents got divorced, and she literally stopped eating, losing 10 kilos in a 6-month period and reaching a BMI of 15. In approximately 1 year’s time, she recovered without taking any specific treatment but continued having restricting eating behaviors during the following years, although not fulfilling the criteria for anorexia nervosa.

The BD onset is collocated at 17, when she experienced her first depressive episode. This was characterized by depressed mood, reduced interest in most of the usual activities, weight loss, feeling of worthlessness, and difficulties in concentrating. She did not seek any medical attention, and the episode remitted approximately within 1 month. She got her high school diploma and was then admitted to the university (economics course).

When she was 19, she experienced her second depressive episode and, at this point, she received her first pharmacological treatment with antidepressants. Such episode resolved over a 2-month period, making her able to return to her university studies. One year later, she interrupted the psychopharmacological treatment. At the age of 22, during a period of study abroad in Germany, the patient experienced her first hypomanic episode, characterized by a persistently elevated mood, grandiosity, decreased need for sleep, and increase in goal-directed and potentially dangerous activities. She did not seek any kind of help and the episode spontaneously remitted in few weeks.

She came back to Italy and, at 24 years old, she had her first hospitalization in a psychiatric ward for a third depressive episode, complicated with a suicide attempt (she cut her forearm). During the hospitalization, hypomanic symptoms were not recognized by the clinicians. Hence, she was dismissed with a diagnosis of recurrent major depressive disorder and an antidepressant therapy. She also fulfilled the criteria for borderline personality disorder. In fact, she showed a pervasive pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image and affects, and marked impulsivity. She often reported unstable and intense interpersonal relationships, characterized by alternating between extremes of idealization and devaluation; recurrent suicidal behavior, gestures, or threats and self-mutilating behavior; affective instability due to a marked reactivity of mood; and chronic feeling of emptiness and inappropriate and intense anger.

After the first hospitalization, the patient did not fulfill the criteria for either a depressive or a hypomanic phase. She experienced frequent mood swings, alterations in her eating behavior, episodic alcohol abuse, and recurrent self-mutilating behaviors, together with a pattern of instability concerning her interpersonal relationships. Nevertheless, she was able to complete her university studies and start working as a researcher in the university where she graduated.

At the age of 26, the second episode of hypomania occurred. This was similar to the first one she experienced and, also in this case, she did not seek any medical help.

In 2015, when she was 27, she went through four different mood episodes, responsible for four hospitalizations: two major depressive episodes and two major depressive episodes with mixed features. The mixed episodes were characterized by depressive symptoms (e.g., depressed mood, psychomotor agitation, diminished ability to concentrate, recurrent thoughts of death) and hypomanic ones (e.g., decreased need for sleep, increased goal directed, and potentially dangerous activities). The psychopharmacological treatment was changed from aripiprazole, lamotrigine, duloxetine, and quetiapine to carbolithium, aripiprazole, and quetiapine. She also started a CBT-oriented psychotherapy.

With this combination of treatments, she has been asymptomatic since 2015. She was able to find a job and a stable relationship.

In conclusion, within an 11-year period since the first episode occurred, the patient experienced nine episodes of illness: five major depressive episodes, two hypomanic episodes, and two major depressive episodes with mixed features (see Fig. 5.3). The BD onset was at the age of 17; the first appropriate treatment was introduced at 27, with a duration of untreated illness of 10 years.

5.3 Literature Review

The above-described case represents an example of coexisting BD and BPD, with the latter being the first diagnosis and BD being diagnosed later on during the course of illness. This aspect may be related to the overlapping symptomatology that frequently delays the time of an appropriate diagnosis.

By reviewing the existing literature on BD and BPD, Ghaemi and colleagues tried to identify similarities and differences between the two disorders in relation to some relevant nosological validators (Table 5.3). Although similar in terms of some variables such as mood lability and impulsivity, they seem to significantly differ with respect to others, including:

-

Past sexual abuse: higher prevalence in BPD vs. BD.

-

Parasuicidal self-harm: twofold increased relative risk in BPD vs. BD.

-

Genetics and neurobiology: BD almost completely genetic with several neurobiological abnormalities vs. BPD mostly environmental in causation with fewer neurobiological alterations. According to a recent genome-wide association study of BPD, a genetic overlap with BD, major depressive disorder, and schizophrenia emerged, suggesting the existence of an etiological overlap with the major psychoses [38].

-

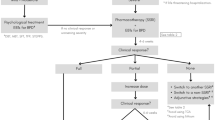

Treatment response: in BD the approach is based on an appropriate psychopharmacological treatment, with psychotherapies being adjunctive, whereas BPD requires psychotherapies as central to its management, with psychotropics being adjunctive [7] (Table 5.3).

Considering the frequent co-occurrence of BD and BPD, which, as shown in our case, may highly impact the course of illness and its outcome [39], the mainstay of the treatment approach in BPD is based on integrated psycho-/pharmacotherapy. Controlled treatment trials provide initial evidence on the efficacy of pharmacological interventions in the treatment of personality disorder signs and symptoms. A dimensional perspective is encouraged, in order to target symptoms’ domains: for instance, BPD patients with affective instability or transient depression may benefit from the use of SSRIs, mood stabilizers, and/or atypical antipsychotics, the latter being useful also in the case of psychotic-like symptoms. SSRIs and mood stabilizers may help also in cases of impulsivity or aggression, whereas antidepressants in general are indicated in patients with anxiety.

Moreover, it is worth considering that several studies showed a higher risk of new-onset BD in BPD patients compared to subjects with other personality disorders, in particular 1.1–16.9 times for BD I and 2.1–9.5 times for BD II [10, 40,41,42].

In addition, the clinical history of the patient including various suicide attempts leads to some considerations about the enhanced risk of suicide attempts in cases of comorbidity between BD and BPD. The suicide risk in BD is among the highest within the psychiatric conditions. In fact, approximately one-fourth of BD I patients and one-fifth of BD II subjects attempt suicide in their lifetime [43], with a pooled suicide rate of 164 per 100,000 persons-years and accounting for 3.4–14% of all suicide deaths. The prevalence of attempted suicide in BD II and I does not appear to be significantly different, although BD II patients seem to use significantly more violent and lethal methods than those with BD I [44]. Depressive onset in BD has been associated with a greater rate of lifetime suicide attempts, with a 2.4-fold risk [45].

Moreover, according to the APA, up to 10% of individuals meeting criteria for BPD eventually commit suicide. Tsanas and colleagues reported suicide rates in BPD ranging between 6 and 8% as well as non-suicidal self-injurious behaviors in up to 90% of patients [46].

This prevalence rate may be even higher considering patients showing the two comorbid conditions. For instance, the comorbidity with cluster B/borderline personality disorder is among the variables significantly associated with suicide attempts in BD.

The present clinical case also sheds light on the issue regarding the prescription of antidepressants in BD patients, as in this patient their use probably induced an acceleration of cycling.

Most of the international guidelines in the treatment of BD (APA, WFSBP, CANMAT, NICE) discourage the prescription of antidepressant monotherapy in depressed patients, especially BD I, because of the enhanced risk of relapses and recurrences as well as suicide attempts, with a significant impact on clinical outcome [47, 48].

Some evidence supports their use in combination with an antimanic agent and for a limited period of time, within the resolution of the acute phase. They should be avoided in case of rapid cycling, previous cycle acceleration, or switching to manic phases during an antidepressant treatment with a concomitant mood stabilizer [49, 50].

Nevertheless, the risk/benefit ratio often leans toward the prescription of antidepressants, apparently widely used in BD [51,52,53], also during hypomanic/manic phases. Their prevalence rate seems to be higher in European countries [54] compared with American ones [55,56,57,58,59].

The use of antidepressants may be due, on one hand, to the misdiagnosis of BD as unipolar depression, reported in approximately 40% of cases [60] and responsible for a significant extension of the untreated illness period.

On the other hand, when BD is properly diagnosed, the antidepressant prescription may be related to the fact that depressive symptoms tend to last longer compared with hypomanic/manic ones [61, 62]. The administration of antidepressants may also be explained by the frequent comorbidity with anxiety disorders, even considering that anxious symptoms seem to last more than those of any other phase [63].

In literature, some authors reported that euthymic patients with residual symptoms, comorbid psychiatric disorders, and unsatisfactory global functioning may present an insufficient response to lithium [64], thus potentially explaining the tendency to choose antidepressants.

In addition, given that BD patients (especially II) are frequently less aware of elevation mood and other activation symptoms—often mild and difficult to recognize—they don’t come to clinical attention and antidepressant treatment is continued beyond the necessary period.

5.4 Conclusions

The present case report draws attention to the challenges associated with the diagnosis and treatment of a wide population of psychiatric patients, whose symptoms and clinical history appear to be intermediate—or somehow overlapping—between BD and BPD, considered as distinct disorders according to the current nosography.

To date, evidence coming from the available literature does not allow us to resolve the debate regarding the nosological distinction between these two disorders. In particular, it’s still uncertain if, on one hand, they should be considered as separate disorders that may, in some cases, simultaneously occur, or, on the other hand, they may take place within a continuum, either from an etiological or symptomatological point of view.

In the latter case, some features may point to the clinical picture as being intermediate, rather than related to distinctive phases of illness and, hence, to different disorders. The absence of clear manic lifetime episodes in our patient may support such a perspective, as the prevalence of mixed symptoms over the course of illness made the clinical presentation closer to the typical BPD picture. Furthermore, in her history, some of the intrinsic BPD characteristics, such as self-cutting, binge eating, substance abuse, and explosive anger, occurred almost exclusively during depressive or mixed phases. For instance, when the patient achieved an adequate mood stabilization, no such pathological personality features—by definition stable in BPD—emerged.

In support of the continuity between the two disorders, it is worth further underlining that recent genetic studies documented a significant overlap between these two conditions in pathogenetic terms. In our case, the familial anamnesis could not help us in potential investigation of the different genetic pools involved in the two disorders.

Finally, the present case report underlines some relevant therapeutic implications: antidepressant use, although hypothetically explained by the prevalence of depressive episodes, may have raised the emotional component, thus leading more easily to impulsive behaviors, more rapid cycles, and higher suicidality risk. The introduction of lithium—following the antidepressants’ interruption—represented a decisive turning point in the clinical history of our patient. The achieved mood stability smoothed the pathological personality alterations, till they gradually disappeared. The psychotherapeutic intervention aimed to provide education about her everyday lifestyle, in particular to introduce changes in dietary and physical activity habits, to promote abstinence from substance and alcohol use, and to enhance the circadian rhythm integrity, during both depressive and hypomanic phases. This helped the patient to reduce her mood instability and related consequences on the behavioral levels. Among the other therapeutic focuses, the interpersonal relationships and self-esteem, which at first appeared to be significantly impaired, thus led to precipitate critical phases of illness, with repercussions on behavior and mood.

Key Points

-

BD and BPD have high comorbidity rates.

-

BD and BPD share some core symptoms, such as affective instability and impulsivity, and there is an ongoing debate on whether BPD should be considered within the bipolar spectrum.

-

When BD occurs with BPD, it has particular clinical features that are important to consider, such as earlier age of onset, higher suicidality rates, high-lethality suicidal behavior, and increased number of mood episodes.

-

The underestimation of comorbidity rates could lead to a significant delay in diagnosis and planning of appropriate treatments.

-

Antidepressant use may raise the emotional component of BPD patients, thus leading more easily to impulsive behaviors, more rapid cycles, and higher suicidality risk.

References

Grande I, Berk M, Birmaher B, Vieta E. Bipolar disorder. Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1561–72.

Tomko RL, Trull TJ, Wood PK, Sher KJ. Characteristics of borderline personality disorder in a community sample: comorbidity, treatment utilization, and general functioning. J Personal Disord. 2014;28:734–50.

Lieb K, Zanarini MC, Schmahl C, et al. Borderline personality disorder. Lancet. 2004;364:453–61.

Galione J, Zimmerman M. A comparison of depressed patients with and without borderline personality disorder: implications for interpreting studies of the validity of the bipolar spectrum. J Personal Disord. 2010;24:76372.

Parker G. Is borderline personality disorder a mood disorder? Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204:252–3.

Barroilhet S, Vohringer PA, Ghaemi SN. Borderline versus bipolar: differences matter. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;128:385–6.

Ghaemi SN, Dalley S, Catania C, Barroilhet S. Bipolar OR borderline: a clinical overview. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130(2):99–108.

Zimmerman M, Morgan TA. Problematic boundaries in the diagnosis of bipolar disorder: the interface with borderline personality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15:422.

Fornaro M, Orsolini L, Marini S, De Berardi D, et al. The prevalence and predictors of bipolar and borderline personality disorders comorbidity: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;195:105–18.

McDermid J, Sareen J, El-Gabalawy R, et al. Comorbidity of bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;58:18–28.

Sajatovic M, Blow FC, Ignacio RV. Psychiatric comorbidity in older adults with bipolar disorder. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:582–7.

Goldberg JF, Garno JL. Age at onset of bipolar disorder and risk for comorbid borderline personality disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11:205–8.

Moor S, Crowe M, Luty S, et al. Effects of comorbidity and early age of onset in young people with bipolar disorder on self-harming behavior and suicide attempts. J Affect Disord. 2012;2012(136):1212–5.

Neves FS, Malloy-Diniz LF, Correa H. Suicidal behavior in bipolar disorder: what is the influence of psychiatric comorbidities? J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:13–8.

Perugi G, Angst J, Azorin JM, BRIDGE Study Group, et al. The bipolar-borderline personality disorders connection in major depressive patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;128:376–83.

Carballo JJ, Harkavy-Friedman J, Burke AK, et al. Family history of suicidal behavior and early traumatic experiences: additive effect on suicidality and course of bipolar illness? J Affect Disord. 2008;109:57–63.

Carpiniello B, Lai L, Pirarba S, et al. Impulsivity and aggressiveness in bipolar disorder with co-morbid borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2011;188:40–4.

Garno JL, Goldberg JF, Ramirez PM, Ritzler BA. Bipolar disorder with comorbid cluster B personality disorder features: impact on suicidality. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:339–45.

Swann AC, Lijffijt M, Lane SD, Steinberg JL, Moeller FG. Antisocial personality disorder and borderline symptoms are differentially related to impulsivity and course of illness in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;148:384–90.

Yen S, Frazier E, Hower H, et al. Borderline personality disorder in transition age youth with bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;132(4):270–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12415

Zeng R, Cohen LJ, Tanis T, et al. Assessing the contribution of borderline personality disorder and features to suicide risk in psychiatric inpatients with bipolar disorder, major depression and schizoaffective disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2015;226:361–7.

Neves FS, Malloy-Diniz LF, Romano-Silva MA, et al. Is the serotonin transporter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) a potential marker for suicidal behavior in bipolar disorder patients? J Affect Disord. 2010;125:98–102.

Oquendo MA, Bongiovi-Garcia ME, Galfalvy H, et al. Sex differences in clinical predictors of suicidal acts after major depression: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:134–41.

Joyce PR, Light KJ, Rowe SL, Cloninger CR, Kennedy MA. Self-mutilation and suicide attempts: relationships to bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, temperament and character. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2010;44:250–7.

Wilson ST, Stanley B, Oquendo MA, et al. Comparing impulsiveness, hostility, and depression in borderline personality disorder and bipolar II disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1533–9.

Hidalgo-Mazzei D, Walsh E, Rosenstein L, Zimmerman M. Comorbid bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder and substance use disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203:54–7.

Perroud N, Cordera P, Zimmermann J, et al. Comorbidity between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and bipolar disorder in a specialized mood disorders outpatient clinic. J Affect Disord. 2014;168:161–6.

Preston GA, Marchant BK, Reimherr FW, et al. Borderline personality disorder in patients with bipolar disorder and response to lamotrigine. J Affect Disord. 2004;79:297–303.

Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-depressive illness: bipolar disorders and recurrent depression. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

Henry C, Mitropoulou V, New AS, et al. Affective instability and impulsivity in borderline personality and bipolar II disorders: similarities and differences. J Psychiatr Res. 2001;35:307–12.

Perugi G, Fornaro M, Akiskal HS. Are atypical depression, borderline personality disorder and bipolar II disorder overlapping manifestations of a common cyclothymic diathesis? World Psychiatry. 2011;10:45–51.

Mackinnon DF, Pies R. Affective instability as rapid cycling: theoretical and clinical implications for borderline personality and bipolar spectrum disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:1–14.

Akiskal HS. The temperamental borders of affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1994;379:32–7.

Angst J, Gamma A. A new bipolar spectrum concept: a brief review. Bipolar Disord. 2002;4:11–4.

Nagata T, Yamada H, Teo AR, et al. Using the mood disorder questionnaire and bipolar spectrum diagnostic scale to detect bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder among eating disorder patients. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:69.

Perugi G, Akiskal HS. The soft bipolar spectrum redefined: focus on the cyclothymic, anxious-sensitive, impulse-dyscontrol, and binge-eating connection in bipolar II and related conditions. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2002;25:713–37.

Koenigsberg H. Affective instability: toward an integration of neuroscience and psychological perspectives. J Personal Disord. 2010;24:60–82.

Witt SH, et al. Genome-wide association study of borderline personality disorder reveals genetic overlap with bipolar disorder, major depression and schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7(6):e1155.

Frias A, et al. Anxious adult attachment may mediate the relationship between childhood emotional abuse and borderline personality disorder. Personal Ment Health. 2016;10(4):274–84.

Grant BF, et al. Sociodemographic and psychopathologic predictors of first incidence of DSM-IV substance use, mood and anxiety disorders: results from the wave 2 national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:1051–66.

Gunderson JG, et al. Interactions of borderline personality disorder and mood disorders over 10 years. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;75:829–34.

Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Vujanovic AA, Hennen J, Reich DB, Silk KR. Axis II comorbidity of borderline personality disorder: description of a 6-year course and prediction to time-to-remission. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110:416–20.

Merikangas KR, et al. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(3):241–51.

Novick DM, et al. Suicide attempts in BD I and II disorder: a review and meta-analysis of the evidence. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(1):1–9.

Cremaschi L, et al. Onset polarity in BD: a strong association between first depressive episode and suicide attempts. J Affect Disord. 2017;209:182–7.

Tsanas A, Saunders KE, Bilderbeck AC, Palmius N, Osipov M, Clifford GD, et al. Daily longitudinal self-monitoring of mood variability in bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder. J Affect Disord. 2016;205:225–33.

Altamura AC, Percudani M. The use of antidepressants for long-term treatment of recurrent depression: rationale, current methodologies, and future directions. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54(Suppl):29–37. discussion 38; Review

Ghaemi SN, Hsu DJ, Soldani F, Goodwin FK. Antidepressants in bipolar disorder: the case for caution. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5(6):421–33.

Nivoli AM, Colom F, Murru A, Pacchiarotti I, Castro-Loli P, González-Pinto A, Fountoulakis KN, Vieta E. New treatment guidelines for acute bipolar depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2011;129(1–3):14–26.

Post RM. Bipolar depression dilemma: continue antidepressants after remission or not? Curr Psychiatr Ther. 2004;3(7):40–9.

Grande I, de Arce R, Jiménez-Arriero MÁ, Lorenzo FG, Valverde JI, Balanzá-Martínez V, Zaragoza S, Cobaleda S, Vieta E, SIN-DEPRES Group. Patterns of pharmacological maintenance treatment in a community mental health services bipolar disorder cohort study (SIN-DEPRES). Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16(3):513–23.

Kessing LV, Vradi E, Andersen PK. Nationwide and population-based prescription patterns in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2016;18(2):174–82.

Post RM, Leverich GS, Kupka R, Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Altshuler LL, Frye MA, Rowe M, Grunze H, Suppes T, Nolen WA. Clinical correlates of sustained response to individual drugs used in naturalistic treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2016;66:146–56.

Frangou S, Raymont V, Bettany D. The Maudsley bipolar disorder project. A survey of psychotropic prescribing patterns in bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2002;4(6):378–85.

Jarema M. Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of mood disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(1):23–29 [J Psychopharmacol 26(5):603–17].

Depp C, Ojeda VD, Mastin W, Unützer J, Gilmer TP. Trends in use of antipsychotics and mood stabilizers among Medicaid beneficiaries with bipolar disorder, 2001–2004. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(10):1169–74.

Ghaemi SN, Hsu DJ, Thase ME, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Miyahara S, Sachs G. Pharmacological treatment patterns at study entry for the first 500 STEP-BD participants. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(5):660–5.

Russo P, Smith MW, Dirani R, Namjoshi M, Tohen M. Pharmacotherapy patterns in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2002;4(6):366–77.

Baldessarini RJ, Leahy L, Arcona S, Gause D, Zhang W, Hennen J. Patterns of psychotropic drug prescription for U.S. patients with diagnoses of bipolar disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(1):85–91.

Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Chiou AM, Pandurangi AK, Goodwin K. Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? J Affect Disord. 1999;52(1–3):135–44.

Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ, Valentí M, Pacchiarotti I, Tondo L, Vázquez G, Vieta E. Bipolar depression: clinical correlates of receiving antidepressants. J Affect Disord. 2012;139(1):89–93.

Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, Vázquez G, Lepri B, Visioli C. Clinical responses to antidepressants among 1036 acutely depressed patients with bipolar or unipolar major affective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127(5):355–64.

McIntyre RS, Rosenbluth M, Ramasubbu R, Bond DJ, Taylor VH, Beaulieu S, Schaffer A, Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Task Force. Managing medical and psychiatric comorbidity in individuals with major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2012;24(2):163–9.

Bowden CL. Novel treatments for bipolar disorder. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2001;10(4):661–71.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Self-Assessment Questionnaire

Self-Assessment Questionnaire

-

1.

What is the estimated prevalence of BPD among BD subjects?

-

(A) 10% of BD II and 20% of BD I patients

-

(B) 20% of BD II and 10% of BD I patients

-

(C) 5% of BD II and I patients

-

(D) 0.1% of BD II and I patients

-

-

2.

Which of the following is a core symptom of both BD and BPD?

-

(A) Depressed mood

-

(B) Hypomanic symptoms

-

(C) Affective instability

-

(D) Anxiety

-

-

3.

Which condition could be a risk factor for rapid cycling?

-

(A) Alcohol abuse

-

(B) History of childhood trauma

-

(C) Antidepressant treatment

-

(D) History of suicide attempts

-

-

4.

Compared to BD without BPD, BD in comorbidity with BPD has a higher risk of:

-

(A) Heroin abuse

-

(B) PTSD

-

(C) Suicide attempts

-

(D) Agoraphobia

-

-

5.

What is the most efficacious treatment approach for BD?

-

(A) Antipsychotics

-

(B) Mood stabilizers

-

(C) Psychotherapy

-

(D) Antidepressants

-

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Fiorentini, A., Cremaschi, L., Prunas, C. (2019). Bipolar Disorder and Borderline Personality Disorder. In: Altamura, A., Brambilla, P. (eds) Clinical Cases in Psychiatry: Integrating Translational Neuroscience Approaches. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91557-9_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91557-9_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-91556-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-91557-9

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)