Abstract

Lymphadenitis refers to any condition that results in an inflamed lymph node or group of lymph nodes. A careful medical history and physical examination are important when suspecting the diagnosis. Although infection is the most common cause of inflamed lymph nodes, noninfectious etiologies should also be considered. The history of the present illness, including the length of time the symptoms have been present, along with any associated systemic signs or symptoms can provide important clues about the underlying cause. A history of exposure to an infectious agent known to cause lymphadenitis and physical examination findings related to the anatomic location(s) of the affected lymph nodes can also be very useful in narrowing the broad differential diagnosis. By far, the most common causes of acute bacterial lymphadenitis are Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes. As a group, subacute and chronic lymphadenitis is less common than acute infection but carries a much broader differential diagnosis with nontuberculous mycobacteria and Bartonella henselae, the cause of cat scratch disease, becoming the primary considerations. While tuberculosis (TB) is generally considered an infection of the lungs, one of the well-described clinical presentations of extrapulmonary TB is chronic lymphadenitis. Less common microbiologic causes of lymphadenitis include other bacteria, a variety of viruses, several fungi, and at least one parasite. Acute lymphadenitis is often treated empirically with antimicrobial agents effective against S. aureus and S. pyogenes. When the illness is atypical, prolonged, or severe, a diagnostic evaluation that includes blood tests, imaging studies, and screening for TB should be performed. If the diagnosis remains enigmatic despite those efforts, fine needle aspiration, lymph node biopsy, or complete surgical excision of the inflamed lymph node may be necessary. Surgically obtained tissue should be sent for microbiologic studies and for histologic evaluation. Definitive medical treatment depends on the identified underlying cause.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Lymphadenitis

- Lymphadenopathy

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Streptococcus pyogenes

- Bartonella henselae

- Nontuberculous mycobacteria

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- Epstein-Barr virus

- Cytomegalovirus

- Human immunodeficiency virus

- Histoplasma capsulatum

- Francisella tularensis

- Yersinia pestis

- Toxoplasma gondii

-

To review important history and physical examination skills for the assessment of lymphadenitis.

-

To understand the diagnostic approach for lymphadenitis and develop a working differential diagnosis of possible etiologies.

-

To gain familiarity with the usual treatment regimens for lymphadenitis.

1 Introduction to the Problem with Definitions

The lymphatic system is an integral part of the immune system consisting of lymphatic organs, lymph nodes, lymphatic vessels, and lymphatic fluid. Lymph nodes are collections of lymphoid tissue interconnected by lymphatic vessels. In the presence of a nearby infection, lymphatic fluid entering a draining lymph node will carry inflammatory debris which may include the pathogen causing the distal infection. In the presence of this inflammatory milieu, the lymph node “reacts.” Reactive nodes become enlarged, in part because of the inflammatory process and in part because of intra-nodal lymphocyte proliferation, an important component of a healthy adaptive immune response to infection. A reactive lymph node is enlarged and swollen and may be mildly tender. Lymphatic vessels can also carry viable pathogens from the nearby infection into the lymph node. If pathogen replication exceeds the capacity of the protective host immune response, the lymph node itself becomes infected. When S. aureus or S. pyogenes are the invading pathogen, the enlarged, swollen lymph node becomes increasingly erythematous, tender, and warm to the touch. This acutely inflamed lymph node is seen clinically as a red, hot, swollen, painful mass referred to as acute bacterial lymphadenitis [► Call Out Box 3.1]. Acute bacterial lymphadenitis is common during childhood. The most common anatomic location for the infected lymph node is in the neck, where the anterior cervical lymph node chain receives lymphatic drainage from the mouth and oropharynx. Acute respiratory viral infections are frequently associated with “swollen glands ” in the neck as the draining lymph nodes become reactive in response to the infection. In such cases, the enlarged, tender lymph nodes are typically present on both sides and have minimal, if any, associated redness. In contrast, acute bacterial cervical lymphadenitis is unilateral, and the inflamed lymph node(s) is enlarged, tender, red, and warm or hot to the touch.

Cervical lymphadenitis is quite common, but infected lymph nodes can occur in proximity to any distal site that is infected or inoculated with a pathogen. Tracking of an infection along the lymphatic vessel toward the draining lymph node can manifest as acute lymphangitis, appearing as a red, tender linear streak that extends toward the draining lymph nodes. The presence of lymphadenitis, especially when the infection is seen in anatomic locations other than the neck, should trigger a careful history and physical examination for injuries, inoculation sites, or active infections along the anatomic area that is drained by the involved node.

Although often used interchangeably, lymphadenopathy and lymphadenitis describe different pathologies. Lymphadenopathy refers to enlarged lymph nodes. Conditions associated with the presence of “reactive” lymph nodes are therefore associated with lymphadenopathy. Lymphadenitis refers to inflamed lymph nodes. Acute or chronic infection of a lymph node itself elicits a local inflammatory response. As such, infection isolated to a lymph node results in lymphadenitis. Noninfectious triggers of inflammation can also cause lymphadenitis, but such pathology is comparatively uncommon.

2 Approach to the Medical History

The history of present illness should include the timing of the onset and the duration of the symptoms, the anatomic location affected, and the presence of any associated symptoms. It should be determined whether the patient has had any injuries, breaks in the skin, punctures, bites, or exposure to pets or wild animals. The past medical history should be reviewed to determine whether underlying host factors predispose the patient to infection with specific pathogens. Asking whether any close contacts have been ill may provide additional clues as to the underlying microbiologic cause. Obtaining a travel history helps to identify infections that should be added to the differential diagnosis that might not otherwise be considered.

Understanding the timing of the onset and the duration of the infection is important to differentiate between acute and chronic disease. Subacute lymphadenitis is defined as symptoms lasting between 2 and 6 weeks; chronic lymphadenitis is present when the problem has persisted for longer than 6 weeks. Acute lymphadenitis is typically caused by suppurative (pus-producing) bacteria, whereas chronic lymphadenitis can be caused by a wide range of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites [1] [► Call Out Box 3.2].

The anatomic location of infected lymph nodes may also provide clues as to the underlying etiology. Generalized reactive lymphadenopathy, a condition where enlarged, sometimes tender, lymph nodes are present in multiple anatomic locations, occurs during infectious mononucleosis caused by Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and as a finding during acute retroviral syndrome secondary to recent infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). At times, during each of these viral infections, one or more lymph node group will appear chronically inflamed. Subacute or chronic cervical lymphadenitis , associated with generalized lymphadenopathy, should raise the possibility that one of these viral infections has trigged the problem. The presence of lymphadenitis in a specific anatomic location other than the neck may alert the astute clinician of a more unusual microbiologic cause. For example, preauricular lymphadenitis is suggestive of adenovirus, B. henselae, or Francisella tularensis infection while post-auricular lymphadenitis is seen with bacterial or fungal infections of the scalp. At first look, this pattern seems completely random, but it is explained by the different anatomic regions drained by the lymph nodes stationed anteriorly and posteriorly to the ear.

Inoculation or infection of the conjunctivae, which may occur during adenovirus infection, exposure to B. henselae after direct contact with a kitten, or exposure to F. tularensis, results in lymphatic drainage to the preauricular lymph nodes. The term “Parinaud’s oculoglandular syndrome” is used to describe the physical examination findings of preauricular lymphadenitis in the presence of ipsilateral palpebral conjunctivitis. Similarly, the scalp lymphatic vessels drain to the posterior auricular lymph nodes, explaining why infections of the scalp, such as severe tinea capitis, can result in post-auricular lymphadenitis.

Obtaining a detailed exposure history is also important when considering potential causative agents of an infected lymph node. Scratches from a kitten (or less commonly from an adult cat) on the hand or forearm ipsilateral to a subacute or chronically infected epitrochlear (elbow) or axillary lymph node strongly implicate B. henselae. B. henselae is the primary agent of cat scratch disease. Epitrochlear lymph nodes drain the lymphatic vessels of the hand and ulnar aspect of the forearm, while the axillary lymph nodes drain the thoracic wall, breast, and arm. When lymphangitis appears abruptly on a limb proximal to a cat bite or scratch that occurred within the last 12–24 h, Pasteurella multocida is the likely cause, although S. pyogenes remains a consideration since both bacterial infections can be rapidly progressive. Cats can also be a source of human infection with Toxoplasma gondii, a parasitic cause of subacute and chronic lymphadenitis. Transmission of T. gondii results from inadvertent exposure to cat feces, typically during cleaning of the indoor litter box. Like cats, dogs are known to transmit P. multocida through bites or other contacts with saliva. P. multocida infections are usually abrupt, associated with fever, and progress rapidly with lymphangitic progression from the site of the bite or other exposures within 12–24 h. Patients typically seek medical care and receive antibiotic treatment before the draining lymph node develops the clinical appearance of an acute infection. Nontuberculous mycobacteria cause chronic lymphadenitis, a disease seen almost exclusively in preschool-aged children. Bacteria in this group are ubiquitous in soil. Direct exposure to chickens has also been suggested as a risk factor [2]. Living or working among cattle outside of the USA may result in an exposure to and infection with Brucella species, another uncommon cause of chronic lymphadenitis. Glandular tularemia refers to subacute or chronic lymphadenitis caused by Francisella tularensis . Exposure typically occurs when an individual is bitten by an infected tick. The bacteria enter the lymphatic vessels draining the area of the tick bite and are carried to the local lymph node(s). If innate host defenses fail to kill the pathogen, the lymph node becomes infected. Individuals who hunt and skin rabbits are at risk for glandular tularemia by directly inoculating F. tularensis into breaks in the skin during the handling of the dead animal. In contrast, the act of skinning a rabbit allows for aerosolization and inhalation of the pathogen. This route of exposure results in the development of life-threatening pneumonia with sepsis, rather than chronic lymphadenitis.

In the course of assessing a patient with lymphadenitis, troubling associated signs and symptoms may become evident. Recent unexpected and unexplained weight loss with an associated chronic cough, especially with intermittent hemoptysis, should be assumed to be tuberculosis until proven otherwise. Patients who present with generalized lymphadenopathy associated with weight loss, fatigue, or pallor should be evaluated for infection with EBV, CMV, and HIV, while other serious noninfectious causes are also entertained, such as hematologic malignancies and lymphoproliferative disorders.

3 Approach to the Physical Examination

Abnormal findings during a careful, comprehensive physical examination are often essential to uncovering a definitive diagnosis. Inspection of the lymph node(s) identified by the patient as part of their chief complaint is essential. The assessment should include an inspection of the overlying skin and the determination of number, size, shape, texture, mobility, and anatomic location(s) of the affected lymph nodes. The presence of a single inflamed lymph node suggests a localized bacterial infection. The presence of inflamed lymph nodes on both sides of a single anatomic location (e.g., bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy or, less commonly, lymphadenitis) suggests a viral infection. Generalized lymph node involvement indicates a systemic process and expands the differential diagnosis to include a variety of noninfectious possibilities. The size of the lymph node(s) is also important. Cervical lymph nodes are considered enlarged when exceeding 10 millimeters in diameter [1], while inguinal lymph nodes are considered enlarged when measuring more than 15 millimeters in diameter [3]. Normal, healthy lymph nodes are easy to find during a routine physical examination, especially in children. When encountered, they are small, nontender, rubbery in texture, and easily moved around under the skin surface during palpation. Reactive lymph nodes are larger, sometimes modestly tender, rubbery but with a denser texture than nonreactive, normal lymph nodes, and easily mobile under the surface of the skin. Lymph nodes that are acutely infected with S. aureus or S. pyogenes are enlarged, firm, exquisitely tender, and warm to the touch. The overlying skin may also be acutely inflamed with associated redness, warmth swelling, and tenderness. The characteristics of the involved lymph node(s) and surrounding tissue can change over time to become an inflamed fluctuant mass as an abscess is formed. Physical examination findings of chronic lymphadenitis lack the “angry” features of acute inflammation but are typically bothersome to the patient nonetheless. Redness or violaceous discoloration of the skin may be appreciated. The affected lymph node(s) are enlarged and may be modestly tender. In comparison, enlarged lymph nodes that are hard and fixed suggest the presence of a malignancy. The observed findings of the involved lymph nodes are very helpful in the development of the differential diagnosis but do not obviate the need to complete the physical examination. The presence of abnormal lymph nodes in one location demands a full body lymph node survey to ascertain whether the abnormal lymph node exists in isolation. Other physical examination finders should be noted, as they may indicate important clues about the patient’s diagnosis.

The location of lymphadenitis also provides a clue as to the underlying etiology of the infection based on the types of problems typically affecting the anatomical area draining lymph fluid to that lymph node. The scalp should be inspected carefully if posterior occipital or posterior auricular lymph nodes are inflamed. Cervical lymphadenitis is more common in children than in adults because of the higher rates of upper respiratory viral and bacterial infections in this age group. Chronic cervical lymphadenitis in a patient with poor dental hygiene or a history of recent dental surgery should heighten the suspicion for anaerobic bacterial infection, particularly from Actinomyces species. The lymphadenitis seen with chronic cervicofacial actinomycosis is also known as “lumpy jaw.” The infected lymph nodes can feel quite hard on palpation and are not typically freely mobile suggesting the possibility of a malignancy, such as lymphoma. Lymphatic actinomycosis can also occur in the abdomen following surgery or penetrating trauma.

The physical examination does not allow for direct visualization of deep thoracic or abdominal lymph nodes. Identification of other less specific abnormalities during the cardiopulmonary or abdominal exam may trigger a request for imaging studies that ultimately reveal pathologic mediastinal, intraperitoneal, mesenteric, or retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy or lymphadenitis [► Call Out Box 3.3]. Splenomegaly, with or without hepatomegaly, is a nonspecific finding on the abdominal examination since it can be present during many systemic infections. Lymphadenitis in association with splenomegaly most strongly suggests EBV, CMV, or acute HIV infection.

In addition to examining the skin overlying the infected lymph node, a survey should be performed in search of evidence of an entry site for the infection. Breaks in the skin or any healing evidence of any cuts, scrapes, puncture wounds, or bite marks should be noted. Pointing out their presence to the patient may trigger an important memory of a prior event that was responsible for the exposure that led to the infection.

4 Diagnostic Testing Used to Evaluate Inflamed Lymph Nodes

Laboratory testing is not always necessary during the evaluation of a patient with suspected lymphadenitis. The presence of history and physical examination findings that are consistent with mild to moderate acute bacterial lymphadenitis in an immunocompetent host with no history of an unusual exposure can be presumed to be infected with S. aureus or S. pyogenes. Empiric treatment can be prescribed with close follow-up to be sure the patient improves as expected. A throat culture for S. pyogenes should be collected prior to the first dose of antibiotics. Patients who fail to improve during empiric antibiotic therapy should be reassessed. While it’s tempting to assume that the failure to improve indicated a flawed empiric diagnosis, the usual explanation is that the infection has organized into an abscess in need of surgical drainage. Incision and drainage removes infected material that is under pressure thereby providing some immediate pain relief. The infected material (all of it, not just a swab) should be sent to the microbiology laboratory for testing. In the vast majority of cases, a Gram stain and bacterial culture of the infected material will provide the definitive diagnosis.

In contrast, more extensive diagnostic testing is typically performed during the evaluation of subacute and chronic lymphadenitis. To begin, nearly every evaluation includes a complete blood count (CBC) and one or more blood biomarkers, which are used to gauge the presence and intensity of acute inflammation (erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and/or procalcitonin). Additionally, necessary diagnostic tests are dictated by clues provided from the medical history or physical examination findings. A list of the most commonly performed tests is found in [► Call Out Box 3.4].

A tuberculin skin test, using purified protein derivative (PPD) , should be placed if tuberculosis is suspected. Positive results implicate M. tuberculosis infection, but the skin test can also be positive secondary to exposure to, or infection with, nontuberculous mycobacteria and in prior recipients of the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine. Diagnostic testing to evaluate for a patient for suspected tuberculosis can also be done using a blood bioassay. Here, the patient’s lymphocytes are exposed to antigens specific to M. tuberculosis. If the patient has had prior exposure to or infection with M. tuberculosis, the lymphocytes become activated and release interferon gamma. As such, interferon gamma release assays (IGRAs) are more specific than the tuberculin skin test for the diagnosis of M. tuberculosis exposure or infection. In most patients, skin testing using a PPD and blood testing using an IGRA are considered equally sensitive for detecting tuberculosis. An important exception is very young children, where the sensitivity of skin testing may be higher than an IGRA.

A chest radiograph is also indicated during the evaluation of subacute and chronic lymphadenitis to determine whether enlarged intrathoracic lymph nodes are also present and to evaluate for lung infiltrates and other findings suggestive of pulmonary tuberculosis or other types of pneumonia that can be associated with lymphadenitis or lymphadenopathy such as histoplasmosis.

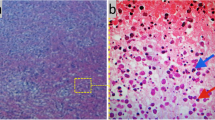

Findings from chest radiography, tuberculin skin testing, IGRAs , and pathogen-specific serologies all offer indirect and/or nonspecific etiologic evidence for the underlying cause of an inflamed lymph node. Direct evidence comes from the lymph node itself. Material obtained during needle aspiration [4, 5], incision and drainage, [6] or excisional biopsy [7] should be sent to both the microbiology and anatomic pathology laboratories. Surgically obtained samples should be evaluated in a comprehensive fashion when sufficient sample is available to avoid the need for a repeat procedure simply because a specific test was omitted during the first evaluation. Diagnostic studies typically requested from the microbiology and anatomic pathology laboratories are found in ► Call Out Box 3.5.

5 Diagnostic Imaging in the Evaluation of Lymphadenitis

Imaging studies are usually unnecessary for the initial evaluation of acute bacterial lymphadenitis. Ultrasonography can be helpful to determine whether an abscess has formed or to localize an abscessed fluid collection in preparation for needle aspiration or incision and drainage [8]. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging modalities are reserved for the evaluation of anatomy when inflamed lymph nodes are suspected to be compressing or obstructing surrounding structures or during a comprehensive diagnostic evaluation for systemic infectious and noninfectious diseases [1].

5.1 General Treatment Considerations

Acute respiratory infections quite often cause reactive cervical lymphadenopathy. Viral infections account for the vast majority of these infections, so treatment with antibiotics is usually unnecessary. Of the long list of respiratory viral infections associated with “swollen glands,” antiviral therapy is only available for influenza. A common bacterial infection to cause reactive cervical lymphadenopathy is group A streptococcal pharyngitis, or “strep throat.” The infection is caused by S. pyogenes and requires antibiotic treatment for the pharyngeal infection even in the absence of acute cervical lymphadenitis. Unlike patients who present with reactive lymphadenopathy, those who present with signs and symptoms of acute bacterial lymphadenitis should be treated with antibiotics. In circumstances where surgical intervention is considered, a brief delay in starting antibiotic therapy is appropriate so that cultures can be obtained prior to treatment unless the patient appears toxic. Patients with persistent or worsening symptoms during or following a course of empiric antibiotic therapy targeting S. aureus and S. pyogenes should be reevaluated as surgical intervention may be required to control the infection [9, 10]. Factors known to increase the need for surgical drainage include younger age, multiple prior visits for medical attention, and the presence of fluctuance at the site of the infected lymph node [11].

5.2 Specific Treatment Considerations

5.2.1 Acute Bacterial Lymphadenitis

Approximately 90% of acute bacterial lymphadenitis cases are caused by S. aureus and S. pyogenes [12]. Among neonates, Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococcus) is occasionally identified. A recent history consistent with an upper respiratory tract infection, impetigo, or acute otitis media is present in the majority of cases [13]. Empiric treatment with an antibiotic that targets S. aureus and S. pyogenes, such as cephalexin (first-generation cephalosporin), is appropriate unless there is a high suspicion for methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) [14]. In such cases, clindamycin is preferred, being mindful that a small percentage of both S. aureus and S. pyogenes are known to be resistant. Suspected MRSA lymphadenitis can also be targeted empirically with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) with the understanding that resistance is becoming more widespread. Moreover, TMP/SMX is not an effective treatment option for S. pyogenes. Lack of improvement despite antibiotic therapy indicates that a drainage procedure is needed to achieve resolution. When incision and drainage is performed after several days of antibiotic therapy, the infected fluid may not yield a positive culture, but the procedure is therapeutic nevertheless. Positive culture results help to guide further antibiotic treatment since antimicrobial susceptibility data will be available. On occasion an unexpected pathogen is identified in culture that requires a different therapeutic approach.

Acute bacterial lymphadenitis caused by Gram-negative bacilli, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Serratia species, is a very unusual finding and should immediately be recognized as such. As appropriate antibiotic therapy is started, testing for an underlying immunodeficiency should begin. Patients with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) , for example, are especially prone to both common and unusual bacterial and fungal infections because of a defect in their neutrophil oxidative burst activity. This immunodeficiency should come to mind in any patient found to have lymphadenitis caused by a Gram-negative bacillus or Aspergillus species. It’s important to note that patients with CGD are also prone to developing infections with S. aureus.

5.2.2 Cat Scratch Lymphadenitis

Cat scratch lymphadenitis is a subacute or chronic lymph node infection caused by Bartonella henselae . As a nickname, cat scratch disease is preferred over “cat scratch fever” since the majority of patients never develop fever. Infection can occur in draining lymph nodes proximal to any inoculation site, but the disease is the most common cause of axillary lymphadenitis and an almost unique cause of epitrochlear lymphadenitis. The presence of Parinaud’s oculoglandular syndrome with preauricular lymphadenitis and associated granulomatous conjunctivitis should always raise the possibility of B. henselae infection. Involved lymph nodes are enlarged and firm, typically with minimal discomfort on palpation [15, 16]. The classic, early presence of an inflamed papule at the site of cat scratches distal to the infected lymph node is easily overlooked by the patient and has usually disappeared by the time the inflamed lymph node appears. Cat scratch lymphadenitis is self-limited and does not require antibiotic therapy. Complete resolution may require 6 months or longer. Patients may opt for surgical excision of the enlarged lymph node(s) especially when their location and size result in discomfort. Excisional biopsy is also performed when the diagnosis is uncertain since the signs and symptoms overlap with noninfectious illnesses such as lymphoma. Systemic complications of cat scratch disease are uncommon but can include meningoencephalitis and hepatitis. Even with such dramatic manifestations, the benefit of antibiotic treatment is controversial [16]. Immunocompromised patients who develop B. henselae infections, including lymphadenitis, typically require prolonged parenteral antibiotic therapy [17]. Successful treatment using a single antimicrobial agent has been reported with azithromycin, clarithromycin, ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, doxycycline, and rifampin. The optimal choice and necessary duration of treatment are unknown.

5.2.3 Actinomycosis

Lymphadenitis secondary to infection with anaerobic bacteria from the genus Actinomyces is uncommon. A typical case presents as chronic cervicofacial lymphadenitis in a setting of poor dental hygiene or after dental trauma or oral surgery. Actinomyces species are part of the normal microbiome of the human oral cavity and colon [18]. Infected lymph nodes in the craniofacial and cervical regions are called “lumpy jaw” because of their typical woody texture. Since fever is usually low grade or absent [19], a malignancy such as lymphoma is often considered the most likely diagnosis, and a surgical referral for biopsy is made. The collection, transport, and processing of lymph node material destined for tests of malignancy, performed in the anatomic pathology laboratory, include placing the surgical sample in a fixative such as formalin. Tissue fixation is crucial to maintain cellular architecture during histologic evaluation and other tests for malignancy, but the process kills any bacteria that might be present. Since a surgical sample is ideally collected only once, it’s important that the surgical team considers sending a portion of the tissue to the laboratory unfixed so that cultures can be performed. Since the clinical findings for some infections and some malignancies overlap, a wise approach taken by many surgeons is to “culture all suspected tumors and biopsy all suspected infections” [► Call Out Box 3.6]. The most common anatomic sites for lymphatic actinomycosis include the submandibular and anterior cervical lymph nodes. As the infection begins, evidence of overlying cellulitis may appear. Abscess formation is not unusual. Draining sinus tracks may appear along sites of spontaneous drainage to the skin surface or at the anatomic sites of manipulation during needle aspiration or biopsy [17]. Local spread of the infection beyond the lymph node should be expected without treatment. The infection does not respect tissue planes and has a propensity to extend into the adjacent bone. Lymph node biopsy or fine needle aspiration is used to obtain samples for diagnosis. Microscopically, the surgical specimen will reveal long, Gram-positive, filamentous rods and the presence of sulfur granules [19]. The most common pathogenic Actinomyces species are strict anaerobes, so maintaining anaerobic conditions during the collection, processing, and culturing of lymph nodes suspected to harbor the organism is important if culture efforts are to be successful. Even when an excisional biopsy is performed, antibiotic treatment with penicillin or clindamycin is typically recommended for several months [17].

5.2.4 Mycobacterium tuberculosis as a Lymph Node Infection

The vast majority of individuals with tuberculosis (TB) have a pulmonary infection. The second most common manifestation of TB is chronic lymphadenitis, a condition also referred to as scrofula. The incidence of scrofula in the USA is low, but the diagnosis should be considered in patients with chronic lymphadenitis, especially those who are high risk because of a known exposure or the presence of an immunocompromising condition [20]. Anatomically, scrofula is most common along the lymph node chain along one side of the neck. Like other infectious causes of chronic lymphadenitis, TB-infected lymph nodes are firm but mobile and minimally tender. The overlying skin may become reddish brown or violaceous but lacks the warmth and bright red color change seen in acute lymphadenitis. As the infection progresses, the lymph nodes undergo caseous necrosis with abscess development with or without draining sinus tracts to the surface of the skin [17]. When the diagnosis is suspected because of the presence of known risk factors, or based on a level of suspicion because of findings on physical examination, several diagnostic tests should be considered. A tuberculin skin test should be placed, or an interferon gamma release assay requested. A chest radiograph should be done to evaluate the patient for the presence of pulmonary TB. Incision and drainage should be avoided because of the increased risk for the development of chronic draining sinus tracts. Any material obtained from the lymph node should be sent to the microbiology laboratory where an acid fast stain can be performed and appropriate cultures initiated. Direct polymerase chain reaction can be used to detect the presence of M. tuberculosis-specific DNA. Antibiotic resistance to one or more agents commonly used to treat TB infection is widespread, and while non-culture-based methods are starting to be used to identify isolates with resistance to some of the antibiotics, a cultured isolate is still needed to perform more comprehensive susceptibility testing. Initial treatment of TB lymphadenitis includes four medications. The most common initial regimen includes rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol (RIPE therapy). Results of antimicrobial susceptibility testing are used to guide the treatment plan. Definitive cure depends on strict adherence to the prescribed regimen of two or more medications for at least 6 months [20].

5.2.5 Nontuberculous Mycobacteria (NTM) Lymphadenitis

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) can infect both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients alike. Immunocompetent children, typically toddlers and preschoolers, who develop NTM lymphadenitis present with minimally symptomatic unilateral submandibular or cervical lymph node swelling, frequently affecting the region of the parotid gland [17, 21]. As the infection progresses, the overlying and surrounding skin may become reddish brown or violaceous in color. The involved lymph nodes develop a firm texture. Draining sinus tracts may develop as described for TB infection, especially if an incision and drainage procedure is performed. Clinically, NTM lymphadenitis is indistinguishable from TB lymphadenitis. Because of the presence of cross-reacting antigens in the tuberculin skin test purified protein derivative (PPD) , a NTM infection can yield a positive skin test result. Interferon gamma release assays have higher specificity for TB infection than the tuberculin skin test, but their sensitivity in very young children may be suboptimal. A definitive diagnosis of NTM lymphadenitis, therefore, depends on lymph node sampling for acid fast bacterial culture and/or PCR assays. The infection itself is often self-limited in immunocompetent children, but spontaneous resolution can take 6 months or longer. If the infected lymph node(s) are amenable to complete surgical excision, the procedure is curative. Antibiotics have little or no effect on the natural course of the infection, even when the NTM isolate undergoes susceptibility testing in an attempt to guide therapeutic decisions. Immunocompromised patients with NTM lymphadenitis benefit most from surgical removal of the infected material followed by susceptibility-directed antibiotic therapy using a combination of three or more medications. Antibiotic combinations commonly used for the treatment of TB are not effective for the treatment of NTM infections because most other mycobacterial species are resistant to them. Some of the medications and medication classes that have proven useful for in various combinations for the treatment of NTM lymphadenitis in immunocompromised patients include intravenous imipenem/cilastatin, intravenous amikacin, minocycline and other tetracycline derivatives, rifabutin and other rifamycin class antibiotics, levofloxacin and other fluoroquinolone class antibiotics, clarithromycin or azithromycin, and clofazimine [21, 22].

5.2.6 Nocardia Species Lymphadenitis

Lymphadenitis caused by Nocardia species is rare and, when it does occur, is almost always seen in immunocompromised patients. The clinical presentation is similar to that seen with other causes of chronic lymphadenitis. The diagnosis is made when the clinical microbiology laboratory recovers the organism from lymph node biopsy material that was submitted for culture [17]. Nocardia species infections are treated with antibiotics in combination with surgical removal when feasible. The necessary length of antibiotic therapy is measured in months and depends on the severity of the infection, the extent to which the infected material has been removed surgically, and the degree of immunocompromise of the patient. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole remains the drug of choice for most Nocardia species infections, although many isolates are also highly susceptible to penicillins, clindamycin, and linezolid.

5.3 Viral Causes of Generalized Lymphadenopathy

5.3.1 Infectious Mononucleosis: Epstein–Barr Virus and Cytomegalovirus

Infectious mononucleosis is an illness most commonly seen among adolescents and younger adults. Patients present with fever, exudative pharyngitis with tonsillar hypertrophy, splenomegaly, fatigue, and generalized lymphadenopathy. Enlarged lymph nodes are most evident in the neck, axillae, and groin. One or more of the enlarged lymph nodes may persist, and mild to moderate discomfort associated with their presence mirrors the signs and symptoms of chronic lymphadenitis. Epstein-Barr virus is the most common cause of infectious mononucleosis. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) accounts for most of the remaining cases. A complete blood count performed during the acute phase of the illness usually shows an elevated percentage of circulating atypical lymphocytes. The detection of serum heterophile antibodies (a positive “monospot” test) supports the clinical suspicion of EBV infection, but a definitive diagnosis requires serologic testing for the detection of immunoglobulin M (IgM) directed against EBV viral capsid antigen [23]. Acute CMV infection is diagnosed by detecting serum anti-CMV IgM. Treatment for infectious mononucleosis is supportive, with no role for the routine use of antiviral medications or systemic glucocorticoids [24].

5.3.2 Acute Infection with Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Recent infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is associated with an infectious mononucleosis-like illness referred to as acute retroviral syndrome. Between 2 and 4 weeks after HIV exposure, individuals who develop primary infection experience fever, fatigue, and generalized lymphadenopathy [25]. The systemic symptoms may last several weeks to months but eventually subside leaving long-term generalized or regional lymphadenopathy. Mild to moderate discomfort associated with the presence of the swollen lymph nodes mirrors the signs and symptoms of chronic lymphadenitis. HIV infection is diagnosed through the detection of circulating HIV-specific antibodies and/or HIV-specific antigen. Treatment relies on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) with a goal to completely suppress virus replication. Effective antiviral therapy can reduce any residual lymphadenopathy. In cases where HAART therapy is delayed and the patient has already developed a serious cellular immunodeficiency secondary to depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes, antiretroviral therapy can trigger an immune reconstitution syndrome with an associated generalized lymphadenopathy [26].

5.4 Fungal Causes of Lymphadenitis

► Call Out Box 3.2 includes several possible fungal causes of subacute or chronic lymphadenitis. Most are quite rare and will not be discussed further, but infections caused by Histoplasma capsulatum are seen regularly enough to warrant a brief description.

H. capsulatum is one of several dimorphic fungi that can cause chronic lymphadenitis. Infections are usually localized to the lungs, but lymph node infections do occur with or without a primary lung focus. In the USA, histoplasmosis is seen most commonly among individuals who live in or around the Mississippi, Ohio, and Missouri river valleys. Immunocompromised individuals, young children, and the elderly are at higher risk than others for developing infection. In the presence of risk factors, histoplasmosis can disseminate rapidly causing a life-threatening, systemic infection. Diagnosis requires either growth of the mold from the involved lymph node or other systemic sites, but even without positive cultures, serologic testing and/or urinary antigen testing can provide supportive evidence of infection. In immunocompromised patients, and in individuals suspected to have disease extending beyond a single group of lymph nodes, chest radiograph or computed tomography of the head, neck, and chest is useful. The presence of parenchymal lung disease with mediastinal adenopathy is not unexpected. Antifungal therapy is indicated for acute infection in those at high risk, but immunocompetent patients do not always require treatment since the illness is usually self-limited. When treatment is used for lymphadenitis, itraconazole is preferred unless severe systemic infection is also present. Under such circumstances, amphotericin B is administered until clinical improvement is evident, followed by a prolonged course of treatment with itraconazole [17].

5.5 Parasitic Causes of Lymphadenitis

5.5.1 Toxoplasma gondii

Infection with Toxoplasma gondii is referred to as toxoplasmosis. The disease is caused by an obligate intracellular protozoan. While most infections are asymptomatic, previously healthy patients who develop symptoms complain most commonly of swollen and tender cervical or occipital lymph nodes that persist for 4–6 weeks. Immunocompetent individuals have a benign illness that mirrors that described for infectious mononucleosis. The chronic lymphadenitis resolves without specific antibiotic treatment [27, 28]. Patients who are pregnant or immunocompromised can develop serious complications. During pregnancy, the parasite can be vertically transmitted to the fetus causing severe congenital defects. Immunocompromised individuals can develop systemic infection with multisystem disease. Whenever treatment is deemed necessary, pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine are used in combination with folinic acid.

6 Summary

Lymphadenitis is an inflammatory condition of lymph nodes, most often caused by an infection. It can be acute, subacute, or chronic in nature and can be caused by a wide variety of pathogens. A thorough history and physical examination is important as the findings provide hints as to the underlying cause of the infection. Lymphadenitis is more common in children than in adults. The anatomic sites most frequently affected are the lymph node chains in the neck. Diagnostic evaluation may require blood tests, skin testing for TB, imaging, and/or sampling of infected tissue for culture. Antimicrobial therapy is not always needed but, when used, should be directed toward the most likely cause of the infection while the diagnostic evaluation is being completed.

7 Exercises

Please refer to the supplementary information section for answers to these exercises.

-

1.

A previously healthy 3-year-old girl with a 3-day history of sore throat, fever, rhinorrhea, and congestion is found to have an enlarged lymph node in her neck. It is not red, tender, or fluctuant. Physical examination of her ears, nose, and throat is unremarkable. She appears well and is active and playful in the examination room. A point of care test on a throat swab is negative for group A streptococcus. Of the following, the most appropriate course of action is:

-

A.

Treat the girl with amoxicillin

-

B.

Provide supportive care

-

C.

Obtain blood work, including a complete blood count and C-reactive protein

-

D.

Obtain a computer tomography scan of her head and neck

-

A.

-

2.

Of the following, the most common cause of acute bacterial lymphadenitis is:

-

A.

Actinomyces species

-

B.

Bartonella henselae

-

C.

Staphylococcus aureus

-

D.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

-

A.

-

3.

A previously healthy 18-year-old female complains of generalized fatigue, fever, sore throat, and swollen, sore glands in her neck of 3 days’ duration. On abdominal examination she has mild left upper quadrant tenderness. The spleen is palpable at the costal margin. A throat swab for group A streptococcus, and a blood heterophile antibody test are both negative. Of the following tests, which is most likely to reveal the diagnosis?

-

A.

Tuberculin skin test

-

B.

Epstein-Barr-specific anti-IgM against viral capsid antigen

-

C.

Lymph node biopsy

-

D.

Polymerase chain reaction specific for human immunodeficiency virus

-

A.

-

4.

Of the following, the most common cause of subacute unilateral axillary lymphadenitis is:

-

A.

Bartonella henselae

-

B.

Francisella tularensis

-

C.

Staphylococcus aureus

-

D.

Streptococcus pyogenes

-

A.

-

5.

The four cardinal signs of acute inflammation are:

-

A.

Diarrhea, conjunctivitis, erythroderma, and headache

-

B.

Bleeding, warmth, pain, and rash

-

C.

Blisters, swelling, pain, and stiffness

-

D.

Redness, swelling, heat, and pain

-

A.

References

Gosche JR, Vick L. Acute, subacute, and chronic cervical lymphadenitis in children. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2006;15(2):99–106.

Garcia-Marcos PW, Plaza-Fornieles M, Menasalvas-Ruiz A, Ruiz-Pruneda R, Paredes-Reyes P, Miguelez SA. Risk factors of non-tuberculous mycobacterial lymphadenitis in children: a case-control study. Eur J Pediatr. 2017;176(5):607–13.

Belew Y, Levorson RE. Chapter 26. Cervical lymphadenitis. In: Shah SS, editor. Pediatric practice: infectious disease. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009. http://accesspediatrics.mhmedical.com.libproxy1.upstate.edu/content.aspx?bookid=453§ionid=40249691. Accessed 21 May 2017.

De Corti F, Cecchetto G, Vendraminelli R, Mognato G. Fine-needle aspiration cytology in children with superficial lymphadenopathy. Pediatr Med Chir. 2014;36(2):80–2.

Lee DH, Baek HJ, Kook H, Yoon TM, Lee JK, Lim SC. Clinical value of fine needle aspiration cytology in pediatric cervical lymphadenopathy patients under 12-years-of-age. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;78(1):79–81.

Kwon M, Seo JH, Cho KJ, Won SJ, Woo SH, Kim JP, Park JJ. Suggested protocol for managing acute suppurative cervical lymphadenitis in children to reduce unnecessary surgical interventions. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2016;125(12):953–8.

Naselli A, Losurdo G, Avanzini S, Tarantino V, Cristina E, Bondi E, et al. Management of nontuberculous mycobacterial lymphadenitis in a tertiary care children’s hospital: a 20 year experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2017;52(4):593–7.

Collins B, Stoner JA, Digoy GP. Benefits of ultrasound vs computer tomography in the diagnosis of pediatric lateral neck abscesses. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;78(3):423–6.

Reuss A, Drzymala S, Hauer B, von Kries R, Haas W. Treatment outcome in children with nontuberculous mycobacterial lymphadenitis: a retrospective follow-up study. Int J Mycobateriol. 2017;6(1):76–82.

Zimmermann P, Tebruegge M, Curtis N, Ritz N. The management of non-tuberculous cervicofacial lymphadenitis in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2015;71(1):9–18.

Sauer MW, Sharma S, Hirsh DA, Simon HK, Agha BS, Sturm JJ. Acute neck infections in children: who is likely to undergo surgical drainage. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(6):906–9.

Block S. Managing cervical lymphadenitis—a total pain in the neck! Pediatr Ann. 2014;43(10):390–6.

Kelly CS, Kelly Jr. R. Lymphadenopathy in Children. Pediatric surgery for the primary care pediatrician, Part I. Pediatric clinics of North America. 1998; 45(4):875–87. Newland J, Kearns G. Treatment strategies for methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in pediatrics. Pediatr Drugs. 2008;10(6):367–78.

Newland J, Kearns G. Treatment strategies for methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in pediatrics. Pediatr Drugs. 2008;10(6):367–78.

Klotz S, Ianas V, Elliott S. Cat-scratch disease. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(2):152–5.

Kelly CS, Kelly R Jr. Lymphadenopathy in children. Pediatric surgery for the primary care pediatrician, Part I. Pediatr Clin N Am. 1998;45(4):875–87.

Penn E, Goudy S. Pediatric inflammatory adenopathy. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 2015;48:137–51.

Thacker S, Healy CM. Pediatric cervicofacial actinomycosis: an unusual cause of head and neck masses. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2014;3(2):e15–9.

Park JK, Lee HK, Ha HK, Choi HY, Choi CG. Cervicofacial actinomycosis: CT and MR imaging findings in seven patients. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:331–5.

Cruz A, Hernandez JA. Tuberculosis cervical adenitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35(10):1154–6.

Tortoli E. Clinical manifestations of nontuberculous mycobacteria infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:906–10.

Reuss A, Dryzymala S, Hauer B, von Kries R, Haas W. Treatment outcome in children with nontuberculous mycobacterial lymphadenitis: a retrospective follow-up study. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2017;6(1):76–82.

Womack J, Jimenez M. Common questions about infectious mononucleosis. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(6):372–6.

De Paor M, O’Brien K, Fahey T, Smith SM. Antiviral agents for infectious mononucleosis (glandular fever). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(12):CD011487.

Penn E, Goudy S. Pediatric inflammatory adenopathy. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 2015;48:137–51. Das G, Baglioni P, Okosieme O. Primary HIV infection. BMJ. 2010;341:c4583.

Phillips P, Bonner S, Gataric N, Bai T, Wilcox P, Hogg R, O’Shaughnessy M, Montaner J. Nontuberculous mycobacterial immune reconstitution syndrome in HIV-infected patients: spectrum of disease and long-term follow-up. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1483–97.

Montoya JG, Liesenfeld O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet. 2004;363:1965–76.

Taila, et al. Toxoplasmosis in a patient who was immunocompetent: a case report J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:16.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Thabet, A., Philopena, R., Domachowske, J. (2019). Acute and Chronic Lymphadenitis. In: Domachowske, J. (eds) Introduction to Clinical Infectious Diseases. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91080-2_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91080-2_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-91079-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-91080-2

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)