Abstract

This chapter documents recent trends in international financial flows, based on a newly assembled dataset covering 40 advanced and emerging countries. Specifically, we compare the period since 2012 with the pre-crisis period and highlight three key stylized facts. First, the “Great Retrenchment” that took place during the crisis has proved very persistent, and world financial flows are now down to half their pre-crisis levels. Second, this fall can be related predominantly to advanced economies, especially those in Western Europe, while emerging markets, except Eastern European countries, have been less severely affected until recently. Third, not all types of flows have shown the same degree of resilience, resulting in a profound change in the composition of international financial flows: while banking flows, which used to account for the largest share of the total before 2008, have collapsed, foreign direct investment flows have been barely affected and now represent about half of global flows. Portfolio flows stand between these two extremes, and within them equity flows have proved more robust than debt flows. This should help to strengthen resilience and deliver genuine cross-border risk-sharing. Having highlighted these stylized facts, this chapter turns to possible explanations for and likely implications of these changes, regarding international financial stability issues.

The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Banque de France or the Eurosystem. We are very grateful to Valérie Ghiringhelli, Muriel Metais and Valérie Vogel for outstanding research assistance, and to Jonas Heipertz for additional help. We would like to thank Olivier Blanchard, John Bluedorn, Claudia Buch, Bruno Cabrillac, Menzie Chinn, Aitor Erce, Ludovic Gauvin, Jean-Baptiste Gossé, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, Galina Hale, Romain Lafarguette, Arnaud Mehl, Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, François Mouriaux, Damien Puy, Julio Ramos-Tallada, Romain Rancière, Cédric Tille, Miklos Vari and Frank Warnock for helpful comments and discussions.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

International financial flows play a central role in the international monetary system, not just because they represent the necessary counterpart to trade flows. In good times, they channel savings to the countries and regions of the world where they are most productive. In crisis times, they have the potential to disrupt the domestic financial systems of the most vulnerable countries and therefore constitute a key factor affecting global financial stability. Together with trade flows, international capital flows act as a powerful channel through which domestic shocks are transmitted across borders. International financial flows also represent one of the corner stones of the contemporary “dilemmas” and “trilemmas” that link monetary policy, exchange rates and the capital account (Rey 2013, or Aizenman et al. 2016). Finally, the composition of international capital flows underlines the concept of “global liquidity”, which plays a central role in the international monetary system (CGFS 2011). For all these reasons, close monitoring of international financial flows is essential to assess the state of the global economic environment.

In recent years, international capital flows have registered profound changes, not only in terms of their magnitude but also their geographical patterns and composition by types of flows: foreign direct investment (FDI), portfolio (debt and equity) flows and other investment flows (which represent primarily bank flows; see Box 1 in Sect. 3 for more details). At this stage, the explanatory factors and implications of these changing patterns are not clear; they will likely trigger a debate in academic and policy circles alike. This chapter aims to contribute to this debate by presenting key stylized facts on international financial flows. We focus on gross rather than net flows, which tend to be more commonly analyzed. We outline likely explanatory factors for these developments and sketch out their implications, based on existing research.

The objective here is primarily to get the facts right, but this proves somewhat challenging, as international financial flows are reported for each country, but not for regional aggregates such as advanced and emerging economies or total world flows. Data gaps are a further challenge. The bulk of the analysis relies on the IMF Balance of Payments Statistics, which reports data at a quarterly frequency. We narrow down the analysis to 40 countries,Footnote 1 which represent more than 90% of world gross domestic product (GDP). Our focus is on recent evolutions (2012Q1–2016Q4) which we compare to the pre-crisis period.Footnote 2 The Global Financial Crisis and its immediate aftermath have already been analyzed extensively elsewhere (in particular by Milesi-Ferretti and Tille 2011). In the present chapter, we develop a “retrenchment indicator” which is computed for all countries and for all available sectors (FDI, portfolio equity, portfolio debt, and other investment). We also use long-run statistics for aggregate data to get a historical perspective, and we comment on short-run dynamics when they are particularly interesting.

Overall, three key stylized facts emerge from the exercise. First, gross international capital flows appear to be historically weak and have not recovered from the “Great Retrenchment” (Milesi-Ferretti and Tille 2011) observed in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis. This is true in absolute value (when flows are measured in US dollars) but also when expressed as a percentage of global GDP. The weakness of international capital flows, therefore, not only reflects the sluggishness of the world economy; it goes beyond this, mirroring the recent “global trade slowdown” (Hoekman 2015, or ECB 2016).Footnote 3 Though some might worry that such an evolution is alarming as it could mean, if it persists, that the global economy is becoming more fragmented than it used to be, another interpretation is possible: Given the large pre-crisis expansion in international capital flows, the “low” level observed in recent years could simply constitute a return to normal which is why we term the observed pattern the “New Normal”.

The second stylized fact is that the weakness of international financial flows seems to affect all economic regions, albeit to a different extent. We provide in this chapter a battery of indicators that help monitor the evolution of international flows. Our “retrenchment indicator” is calculated as the difference between the value of these flows in the pre-crisis period (2005Q1–2007Q2) and the post-crisis period (2012Q1–2016Q4), scaled by GDP. The data show that the fall is very broad-based across countries, but it is more pronounced for advanced than for emerging market countries. Among advanced economies, the current level of inflows is back to the level that was registered in the mid-1990s. Among emerging economies, the fall is comparatively smaller, partly because the rise recorded in the decade preceding the Global Financial Crisis was smaller (which in turn could be related to the crises that affected emerging economies in the 1990s, to the lower level of financial development, overall, and to less open financial accounts). Euro area countries, especially those in the so-called periphery, recorded significantly lower flows as a percentage of GDP. This is consistent with the fact that the recovery was slower in these economies. A sectoral decomposition reveals that the fall in financial flows to and from Europe was particularly substantial for bank flows, which can be related to the fact that the European sovereign debt crisis markedly affected the banking sector.

Third, while all types of flows have been affected by the slowdown, some have been significantly more resilient than others, resulting in a marked change in the composition of financial flows. Specifically, FDI flows have fallen relatively less than other types of flows, while other investment flows have plummeted (even turning negativeFootnote 4). We will show below that other investment flows mainly consist of bank flows (and to a certain extent of flows by non-bank financial institutions). Portfolio flows are in the middle, and within this category, debt instruments have fallen much more than equities. As a result of these changes, the composition of international financial flows is now drastically different. Whereas the other investment category used to account for more than 40% of total flows before the crisis, these flows now constitute a small share of the total (14%). By contrast, the share of FDI has roughly doubled, from 24 to 48%. Within the portfolio category, we also see considerable reallocation: before the crisis, portfolio debt used to amount to more than twice the size of equity flows, whereas they are now of roughly equal magnitudes.

Building on existing research, several factors can be put forward regarding the likely causes of these evolutions. Bank flows may have been more strongly affected than other types of flows because of the problems that plagued the banking sector in advanced economies and led them to undertake a deleveraging process. As is well documented by now, the interbank market froze in the wake of the financial crisis, which affected cross-border lending by banks to other financial institutions. The changing composition of international financial flows may, therefore, reflect the disintermediation process that characterizes the global economy. Importantly, local lending by foreign bank affiliates may now substitute cross-border lending (IMF 2015). The role of European banks might be particularly important in explaining the slowdown: on the one hand, one observes a reversal of the so-called “banking glut” (Shin 2012), i.e. funding by European banks on US wholesale funding markets; on the other hand, cross-border intra-European financial intermediation has decreased substantially due to the reversal of flows from core to periphery countries. Another potential explanation that cannot be excluded is that regulatory (and political) pressure forced banks to concentrate on their core business and retrench from foreign markets.

These trends also have implications for financial stability issues. In particular, a stream of the literature has highlighted that the different types of flows typically exhibit different volatilities and do not show the same level of resilience during crises.Footnote 5 One can note that these differences in the volatility of financial flows have been reflected in their respective evolutions since the crisis: noticeably, FDI flows proved more resilient than portfolio and especially banking flows. However, it is still an open question whether the volatility patterns observed previously will prevail in the “New Normal”.

This chapter relates to existing studies that explored the recent evolution of international financial flows. Milesi-Ferretti and Tille (2011) provided an early analysis of the “Great Retrenchment” in international capital flows. They noted, in particular, that bank flows were hit the hardest, and that the retrenchment was shorter-lived for emerging economies. This chapter shows that this retrenchment continued and was even amplified beyond the early stage of the crisis. Bluedorn et al. (2013) have assembled a large database covering 147 countries since 1980 at an annual frequency and 58 countries at a quarterly frequency. They document and highlight the high volatility of international capital flows, with FDI flows being comparatively less volatile than bank and portfolio flows (but these last two types of flows are not fundamentally different in terms of volatility). While they do not find significant differences across country groups—advanced economies versus emerging economies—regarding the volatility of gross flows, they note that advanced economies “experience greater substitutability across the various types of net flows and greater complementarity of gross inflows and outflows”. This chapter also relates to a large strand of the literature that sought to identify the determinants of international capital flows, including Broner et al. (2013), Forbes and Warnock (2012), Fratzscher (2011), Ghosh et al. (2014), Puy (2015), Erce and Riera-Crichton (2015)Footnote 6 and especially the papers that focus on the determinants of bank flows (see e.g. Buch and Goldberg 2015, and the literature reviewed therein). By focusing on gross and not net flows, we also contribute to the analysis put forward by Obstfeld (2012), who emphasizes the role of gross flows. Importantly, however, we focus here predominantly on international capital flows and not stocks (i.e. the international investment position). This is not to say that stocks do not matter, as clearly they do, but flows provide an early evaluation of where stocks are going and catch substantial attention in themselves. This chapter also echoes the analysis of Borio and Disyatat (2015), who emphasize the importance of financing in the analysis of the external sector. We complement recent contributions that focus on the vulnerability of emerging economies to sudden stops of capital flows. Among others, this literature analyzes the role of gross flows separately, aiming to distinguish the impact of inflows from that of outflows (see e.g. Alberola et al. 2016, and the references therein). Finally, while we do not aim to evaluate the impact of capital flows on growth, this chapter relates to the strand of the literature that looks at the short- and long-run effects of capital flows on growth (see, for instance, Blanchard et al. 2015; Reinhart and Reinhart 2009 and the references cited in these papers). We hope that the stylized facts presented here will feed into this debate.Footnote 7

The rest of this chapter is organized as follows. Section 2 focuses on total gross flows (lumping together portfolio, FDI and other investment) for the world as a whole and for the world’s largest countries and regions. Section 3 turns to the composition of financial flows. It outlines some of the possible factors that may explain why some components have been more resilient than others, and suggests the likely implications, for the global economy, of the new composition of financial flows.

2 Global Financial Flows: Dwindling to a Trickle

2.1 The Rise and Fall of Global Financial Flows

The decade preceding the crisis has been one of financial globalization. The ramping-up of international capital flows and the accumulation of external assets and liabilities in the decades preceding the Global Financial Crisis were perhaps even more dramatic than the already impressive acceleration of trade flows and the development of current account imbalances that took place over this period. This can be related to greater capital account openness. Overall, the magnitude of gross inflows in advanced and emerging countries rose markedly up to the 2008–09 Global Financial Crisis, especially for the former (Fig. 1). Comparing the current period with the period immediately before the Global Financial Crisis may be biased, as capital flows were historically high, especially for advanced economies (for emerging economies the rise was less pronounced and the level was lower, partly because of the crises that plagued emerging economies in the 1990s and early 2000s). If one takes a longer perspective, capital flows appear to be back to their mid-1990s level.

When financial globalization matured before the onset of the Global Financial Crisis, orders of magnitude had changed relative to a decade earlier (Milesi-Ferretti and Tille 2011) along various lines:

-

Foreign assets constituted a significantly bigger share of portfolios; the value of those assets also rose relative to GDP generally.

-

Financial globalization had been more pronounced in advanced than in emerging economies, the former receiving more gross inflows than the latter (Fig. 1).

-

The size of current account imbalances and of creditor/debtor positions had become more dispersed (Bracke et al. 2008).

-

The banking sector in advanced economies had been one of the key drivers of financial globalization. Banks extended their international activities during this process, either through cross-border lending or via foreign affiliates, which played an important role in the subsequent period (see Cetorelli and Goldberg 2011, 2012, and the references therein).

With this pre-2008 snapshot in mind, this section offers a bird’s eye review of major stylized facts that emerged since 2008. We document international financial interdependencies by focusing on gross quarterly capital flows—outflows and inflows—since 2005. We deliberately choose to remain mainly at an aggregate level of description in this section, allowing only for a geographical split between advanced economies and emerging economies. Section 3 will dig deeper into sectoral categories of capital flows, breaking down aggregates into foreign direct investment (FDI), portfolio investment and other investment. Based on Balance of Payments data as of the last quarter of 2016, three key stylized facts emerge.

Stylized fact no. 1: The “Great Retrenchment” that took place during the crisis has proved very persistent and international capital flows are now at a lower level than the one observed prior to the crisis.

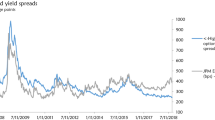

In the years preceding 2008, gross international financial flows were very substantial, hovering around a quarterly aggregate of around 10–15% of global GDP. That was equivalent, back then, to about USD 2,000 bn. The onset of the financial crisis in the summer of 2007 put a “sudden stop” to that flourishing regime: in the first quarter of 2008, these flows were suddenly reduced to nil (Fig. 2).Footnote 8 Aggregate gross flows massively retrenched in the third quarter of 2008, as visible in Fig. 2, when Lehman Brothers collapsed. In that quarter alone, their reversal was equivalent to −10% of global GDP.

Since 2010, gross cross-border financial flows have not returned to the buoyancy of the pre-crisis period. Instead, as of the end of 2016, they seemed to have settled at a “new average” that looks to be below 5% of GDP (Fig. 2). This muted revival raises questions about whether the pre-crisis intensification of global financial linkages, summarized above, was too exuberant.

2.2 The Geographical Pattern of Global Financial Flows: Stylized Facts

Stylized fact no. 2: Advanced economies have been the most affected by the retrenchment in international financial flows.

The retrenchment of global financial flows after the 2008 sudden stop turns out to be predominantly an advanced economy story. In fact, a sharp contrast between advanced and emerging economies emerged after the sudden stop in 2008. Since then, flows to and from advanced countries seemed to have stabilized around an average that was significantly lower than what prevailed before 2008 (Fig. 3).

In emerging markets, gross capital flows were significantly more resilient than in advanced economies already in the early phase of the crisis (Fig. 3). After 2008, capital inflows into emerging economies recovered quickly and even outpaced pre-crisis levels, although the most recent numbers show a downward trend. This is likely related to the underlying drivers of these inflows, namely monetary policy in industrialized countries, in particular the US. While liquidity abundance in advanced economies pushed investors towards emerging economies, this trend has dwindled lately as signals of monetary policy normalization became more apparent.

While emerging economies fared much better than advanced economies after the Global Financial Crisis, the latter account for a much larger share of total flows than emerging markets (the ratio is about 1:10).Footnote 9 As a result, the fall recorded by the former could not be offset by the recovery of the latter, and global flows are now smaller than they were before the crisis.

Looking at capital outflows more closely (left-hand side panel of Fig. 3) suggests that capital outflows from emerging countries have been more resilient than those originating from advanced economies. Within the block of emerging countries, this resilience in international exposure of investors holds less true in Eastern Europe, as shown in the regional breakdown of flows (Fig. 4). The most plausible explanation of the fact that Eastern Europe remains the hardest-hit when it comes to emerging economies is its close relationship with Western Europe, in particular through the banking sector. In contrast to Eastern Europe, Asia and Latin-America generally recorded a rise in both their outflows and inflows (Fig. 4).

We now look beyond aggregate facts and investigate country-level developments. To that purpose, we developed a simple metric, which we call a “retrenchment indicator”. This indicator compares the level at which capital flows settled after the 2008 sudden stop (since the first quarter of 2012 until the last quarter of 2016) with their pre-crisis average over the period 2005Q1 to 2007Q2. We scale this difference by GDP. In particular, we calculate:

The top and bottom 10 countries are presented in Table 1. First, capital flows indeed intensified in many emerging economies and in some “safe havens” such as Luxembourg. As a matter of fact, the intensification of inflows to Luxembourg suggests that “financial centers” have continued to cater to the redistribution of flows across countries. Second, by contrast, the retrenchment of capital flows turns out to be the most severe in Western European countries, including the UK, peripheral Euro area countries and France. Euro area periphery countries such as Spain, Portugal and Ireland were among those economies that received a large amount of inflows prior to the crisis and were therefore subject to a large degree of retrenchment (see also Hale and Obstfeld 2014). Another pattern that seems to emerge is that a large number of countries that were subject to retrenchment are the ones that have large banking systems. We will investigate this issue further in Sect. 3.2 by disaggregating international capital flows by the type of flow to investigate the particular role played by banks.

3 When the Composition of Capital Flows Matters

3.1 Different Components, Different Degrees of Resilience

Stylized fact no. 3: The composition of international capital flows has shifted away from other investment flows (which comprise bank flows) towards more FDI. Portfolio flows have also retrenched; this is mainly due to a contraction in debt flows.

While the previous section focused on aggregate flows, we now turn to the decomposition by the main types of flows. This exercise reveals that the collapse of international financial flows has been very uneven (Fig. 5).Footnote 10 Strikingly, FDI has been very resilient (flows in the post-crisis period are just one notch below their pre-crisis level), whereas flows in the “other investment” category—which comprises bank flows (see Box 1)—have been almost completely wiped out.

Source IMF Balance of Payments Statistics (BoPS) and authors’ calculations. Note Periods: Pre-crisis: 2005Q1–2007Q2, Post-crisis: 2012Q1–2016Q4

Comparison of capital flows before and after the crisis, by financial instrument (% GDP). a Breakdown between portfolio, FDI and other investment (full sample). b Breakdown of the portfolio investment category between debt and equity (restricted sample of the countries reporting the debt and equity categories separately since 2005). This figure shows two sets of figures corresponding to different sample composition. The upper panel reports data for the full sample for the broad categories FDI, portfolio and other investment. The lower panel reports the composition of debt and equity within the portfolio category, for the restricted sample of countries reporting this split since 2005.

Box 1: Other investment in the financial account

In the text, we refer broadly to the other investment category as bank flows as it is generally assumed that they constitute the bulk of this category. This box briefly explains this association by highlighting the differences between banking flows and other subcategories of other investment.

Other investment comprises the following types of financial flows: (1) Other equity, (2) Loans, (3) Currency and deposits, (4) Trade credit and advances and (5) Other accounts receivable/payable. The last four components are categorized as debt instruments. It is not only possible to disaggregate these instruments by the type of flow, but also by the counterparty, notably: (1) Central bank, (2) Deposit-taking corporations, except the central bank (“banks”), (3) General government and (4) Other sectors.

For typical industrialized economies, banks constitute the most important counterparty. Looking at stocks (rather than flows) which are by definition non-negative, International Investment Position (IIP) data show that assets held by banks make up for example 71% in the United Kingdom or 69% in France (data for 2013). However, in economies such as Ireland, United States or Luxemburg, they make up respectively 30%, 41% and 43%. In these cases, the sub-category Other sectors also constitutes a large part. Other sectors can be disaggregated into (1) financial (non-bank) corporations as well as (2) nonfinancial corporations and households. In most industrialized countries, the former outnumbers the latter to a large extent. Thus, while bank flows do constitute a large fraction of other investment, the importance of non-bank financial flows can be quite substantial in some economies and therefore explains the smaller share of banks in these cases.

Portfolio flows come somewhat between these two extremes, but even there, significant heterogeneity prevails: portfolio equity flows have been much more resilient than debt flows, which have halved between the pre- and the post-crisis periods. The resilience of equity flows bodes well for the ability of the economy to withstand forthcoming shocks as it has better risk-sharing properties than debt (Albuquerque 2003). One should underline, nonetheless, that there has not been a substitution between types of flows: all flows have fallen, but in different proportions.

As a result of these different evolutions, the composition of world flows is now fundamentally different from what it used to be before the crisis (Fig. 6). In the pre-crisis period, the other investment category used to constitute the bulk of global flows, with a share of 44%, whereas this share is now about 14%. By contrast, whereas FDI used to represent less than a fourth of the total, in the post-crisis period FDI amounts to 48% of total flows. Finally, the share of portfolio investment has slightly increased, from 32 to 38%. Within the portfolio category, the share of debt has fallen, from two-thirds to about half, compared to the share of equity, which has risen correspondingly (as shown in the lower panel of Fig. 6).

Source IMF Balance of Payments Statistics (BoPS) and authors’ calculations. Note Periods: Pre-crisis: 2005Q1–2007Q2, Post-crisis: 2012Q1–2016Q4

Composition of global financial flows by categories before and after the crisis. As in the previous figure, this figure shows two sets of figures corresponding to different sample composition. The upper panel reports data for the full sample for the broad categories FDI, portfolio and other investment. The lower panel reports the composition of debt and equity within the portfolio category, for the restricted sample of countries reporting this split since 2005.

Before turning to possible explanations for this dramatic change in the composition of global financial flows and its likely implications for the global economy, it is worth exploring the geographical breakdown of the flows. To that aim, we once again use our “retrenchment indicator” which reflects the change in in- and outflows in percentage of GDP. To recall, it is expressed as the difference between the value of these flows in the pre-crisis period (2005Q1–2007Q2) and the post-crisis period (2012Q1–2016Q4), scaled by GDP in the pre-crisis period. Table 2 reports the difference of the post-crisis flows with the pre-crisis flows for the main regions of the world for both inflows and outflows.

Several key findings stand out:

-

First, the collapse of the other investment category can be predominantly attributed to advanced economies: the fall is particularly pronounced for Western Europe. For this region, the flows have been negative in the post-crisis period. This is consistent with the fact that the European crisis affected the banking sector, and led to substantial deleveraging and disintermediation thereafter.

-

For other regions, the evolution of this other investment category has been very different. In particular in Asia, flows in both directions have increased between the two periods. For Eastern European countries, the other investment category has been characterized by retrenchment in both outflows and inflows, with the latter being more pronounced. Overall, the collapse in other investment flows originating from and going to advanced countries (North America and especially Western Europe) was less than compensated by the rise recorded in other regions because the size of these regions in the pre-crisis flows was overwhelming for advanced countries (international financial flows are much larger for advanced economies than for emerging economies).

-

Turning to the other types of flows, one can note that FDI flows have been fairly resilient for most regions of the world; they even show an increase for all regions except Europe. Overall, FDI has retrenched in advanced economies and this is entirely due to the retrenchment in Western Europe.

-

Finally, concerning the portfolio category, we need to distinguish between debt and equity (the former has fallen much more than the latter at the global level). Portfolio debt flows have fallen substantially for Western Europe. By contrast, equity flows have fallen to a smaller extent.

Figure 7 shows the composition of gross flows for outflows and inflows for advanced and for emerging market economies over time. In advanced economies, overall swings into positive or negative territory are mainly driven by the other investment category. A similar pattern can also be observed for inflows into emerging economies. FDI and portfolio flows remain rather stable over time. Whenever one observes large increases or decreases of total flows, this can often be traced back to movements in other investment flows. As this category plays a particular role for total flows, we discuss its behavior in more detail in the next section.

3.2 Changing Composition of International Financial Flows: Explanatory Factors and Implications

The changing composition of international financial flows documented above is a striking feature of the global economic environment. One may wonder what could have triggered this change and what are the likely implications for the world economy. While it is usual to list separately the causes and the consequences for expositional purposes, several factors can be seen both as a cause and a consequence. One obvious factor to underline in this respect is the fact that economic activity has been weak since the Global Financial Crisis; the recovery has regularly disappointed, and international organizations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have repeatedly revised their global growth forecasts downwards (see Chap. 1). Weak economic activity is both an explanatory factor for weak financial flows, and, since negative shocks are transmitted through financial linkages, a consequence. In this respect, the European crisis has played an important role.

Another key factor to underline is that some types of international financial flows seem to be inherently more volatile than others. In this respect, bank flows and portfolio flows are often described as “hot money” (see, for instance, Bluedorn et al. 2013). By contrast, FDI flows are typically more stable over time, which is why they are generally considered as a safer form of financing (in addition to other benefits they carry, such as technological transfers). Also, within portfolio flows, equity flows have been more resilient than debt flows. Yet, overall, the behavior of international financial flows after the Global Financial Crisis reflects the traditional wisdom: the flows that are considered to be the most volatile are precisely those that saw the largest decline.

The different components of financial flows have therefore been faithful to their reputation: “hot money” (with the exception of equity flows) has evaporated quickly, whereas FDI has been more robust. Looking forward, this may suggest more stable flows as the resulting composition is composed mainly of FDI flows. However, other elements need to be considered as well to get a full assessment. Table 3, which presents key statistics on the volatility of the main categories of financial flows during the main subperiods considered here (and for the whole sample), confirm these established stylized facts (bearing in mind of course that both sub-periods are short, thus enabling few observations to calculate these statistics). For instance, FDI, which was less volatile than other investment before the crisis, was also less volatile after the crisis.

The factors behind the collapse in cross-border banking flows have been analyzed in CGFS (2011), which investigates the question of global liquidity and focuses on bank flows as the prime measure of global liquidity. Among the possible explanatory factors, the paper by CGFS (2011) highlights the role of risk aversion for the retrenchment observed in the years following the crisis. High levels of uncertainty have likely contributed to the observed patterns in recent years (see for example Converse 2017, on this topic).

To some extent, the fall in bank flows could be interpreted as a correction from the “global banking glut” that prevailed in the pre-crisis period (Shin 2012), through which European banks helped to enhance intermediation capacities in the US. These considerations represent a convincing argument as to why it is important to look at gross and not just net international financial flows. Meanwhile, recently, McQuade and Schmitz (2017) have looked into the cross-country heterogeneity of gross capital flows. They found, in particular, that gross inflows in the post-crisis period (which is defined slightly differently from ours) were higher for the countries with smaller external and internal imbalances in the pre-crisis period.

The fact that international banking flows have fallen dramatically could also reflect the disintermediation process that intensified in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis. In turn, this process could result from different factors. Several prominent observers have pointed out the effect of tighter financial regulation, which could explain why the banking sector seems to be losing ground, compared to financial markets (see, for instance, Tarullo 2012, 2014; CGFS 2010; Gambacorta and Van Rixtel 2013, etc.). Several studies have also pointed out that the exceptional measures put in place after the crisis have a substantial domestic bias, which could have played a role in the global retrenchment process (see e.g. Beck et al. 2015; Forbes et al. 2015b). Moreover, it is also possible that local lending by affiliates has (partly) replaced cross-border lending. In this respect, the shift from cross-border banking to more activities by foreign affiliates might have a positive impact on financial stability (IMF 2015). Another potential explanatory factor could lie in the recent weakness of international trade flows (as documented, for instance, by Hoekman 2015). Indeed, trade credits are included in the other investment category, such that the weakness of international trade would mechanically affect this type of flow. Indeed, trade credit issues have been highlighted as one of the potential causes of weak trade (see, for instance, Amity and Weinstein, 2011, or Chor and Manova 2012). This notwithstanding, trade credits amount to fairly low levels and cannot account for the fall in investment flows.

4 Conclusion

This chapter has presented three main stylized facts on international financial flows in recent times, focusing on the comparison with the pre-crisis period. (i) Overall, international capital flows have dried up, now averaging at barely half of their pre-crisis level in percentage of world GDP. (ii) In terms of geographical distribution, this fall has mainly affected advanced countries, especially Western Europe, while for emerging market economies flows have actually increased. (iii) The composition of international capital flows has changed dramatically, due to the heterogeneous change in their sectoral composition: bank flows have been very markedly affected, whereas FDI has remained roughly unchanged at the global level. Within portfolio investments, debt flows have fallen much more than equity flows (Western Europe being again the region of the world where debt flows have fallen most).

Several factors can be put forward to explain these changes. They range from general factors, such as the weakness in the global recovery and the associated degree of uncertainty, to more specific factors, affecting certain regions and sectors more than others. Among the latter, the European crisis in 2011–13 seems to have played a key role, as it is really flows to and from Western Europe that decreased the most. Regarding the sectoral composition, several explanations can be put forward for the collapse in bank flows. The need to repair bank balance sheets and the substitution of cross-border flows by local lending by affiliates have been documented extensively. In addition, regulation may have played an important role (see IMF 2015, for instance).

The consequences of these changes for financial stability are not clear at this stage. The changes that have taken place since the Global Financial Crisis may correspond to a simple normalization, as suggested for instance by Coeuré (2015), after rather “exuberant” times in the pre-crisis period. The fact that the share of “hot money” has gone down while that of FDI has increased may lead to a more stable international monetary system, but the concept of “hot money” remains somewhat elusive (bearing in mind that many operations under the other investment flows contribute to the liquidity of markets) and it is hard to gauge if the pre-crisis properties and specificities of the various types of flows that we focused on will prevail in the “New Normal”.

Notes

- 1.

These countries are: Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, United Kingdom and the United States. The aggregate flows reported in Sects. 2 and 3 below are based on individual Euro area countries, thus taking into account intra-Euro area flows.

- 2.

We define the pre-crisis period as 2005Q1–2007Q2 (2005 is the first year of the IMF BPM6 database). Taking this period as benchmark should not be interpreted in a normative way, especially given that this period was likely characterized by exceptional buoyancy of capital flows.

- 3.

International trade flows appear very weak compared to pre-crisis levels, which in itself is not very surprising given that economic activity is also less robust. More strikingly, global trade, which used to increase at twice the pace of global GDP, is now growing at roughly the same pace, suggesting that the relation between trade and GDP has changed, owing to a combination of cyclical and structural factors, as outlined in Hoekman (2015).

- 4.

We consider here gross outflows (i.e. net purchases of foreign assets by domestic residents), and gross inflows (i.e. net purchases of domestic assets by foreign residents). As a result, gross flows may become negative. For instance, if foreign residents sell domestic assets massively, this will result in negative gross inflows.

- 5.

Conventional wisdom states that FDI flows represent a more stable source of external financing compared to portfolio and bank flows (in addition to other benefits, including the technology transfers they may entail); see e.g. Levchenko and Mauro (2007) or Albuquerque (2003). However, the extent to which they are indeed more stable is debated; see, for instance, Brukoff and Rother (2007), Bluedorn et al. (2013) and the references cited therein. The relative stability of different types of capital flows has crucial implications for capital account openness and in particular its sequencing (see e.g. Kaminsky and Schmukler 2003, or Bussière and Fratzscher 2008).

- 6.

These papers take mostly an empirical approach; see Tille and Van Wincoop (2010) for a theoretical view.

- 7.

- 8.

In this section and in the rest of the paper (except where otherwise indicated), we use quarterly data from the IMF BoP Statistics, which start in 2005.

- 9.

The difference partly reflects the fact that several advanced economies, like the UK and Luxembourg, are financial hubs, such that flows to and from these centers are hard to attribute to specific countries. In addition, advanced economies comprise the Euro area where cross-border financial integration is particularly high.

- 10.

In this section we focus on international capital outflows. In principle, the data should match the data series for inflows at the world level. However, due to statistical errors and since our database does not include all countries in the world, global outflows and inflows do not match exactly. In spite of these discrepancies, the data for global inflows lead to the same conclusions, in terms of which flows have been the most resilient. Another challenge is that not all countries report the split between debt and equity in the “portfolio” category, or at least not since 2005. To provide a meaningful comparison, we have therefore split Figs. 5 and 6 in two, showing first the broad “portfolio” category for the whole sample, and then the debt/equity split for the restricted sample of countries, losing in the process Argentina, China, India, Mexico and Turkey. We also omitted Saudi Arabia for data availability reasons related to other investment flows.

References

Aizenman J, Chinn MD, Hiro I (2016) Monetary policy spillovers and the trilemma in the new normal: Periphery country sensitivity to core country conditions. J Int Money Finance 68(C):298–330

Albuquerque R (2003) The composition of international capital flows: risk sharing through foreign direct investment. J Int Econ 61(2):353–383

Alberola E, Erce A, María Serena J (2016) International reserves and gross capital flows dynamics. J Int Money Finance 60(C):151–171

Amiti M, Weinstein D (2011) Exports and financial shocks. Q J Econ 126(4):1841–1877

Beck R, Beirne J, Paternò F, Peeters J, Ramos-Tallada J, Rebillard C, Reinhardt D, Weissenseel L and Wörz J (2015) The side effects of national financial sector policies: framing the debate on financial protectionism, Occasional Paper Series, No 166, September 2015

Blanchard OJ, Chamon M, Ghosh AR, Ostry JD (2015) Are capital inflows expansionary or contractionary? Theory, policy implications, and some evidence. Centre for Economic Policy Research Discussion Papers, DP10909

Bluedorn JC, Duttagupta R, Guajardo J, Topalova P (2013) Capital flows are fickle: anytime, anywhere. International Monetary Fund, working papers 13/183

Borio C, Disyatat P (2015) Capital flows and the current account: taking financing (more) seriously. Bank for International Settlements, working paper No. 525

Bracke T, Bussière M, Fidora M, Straub R (2008) A framework for assessing global imbalances. European Central Bank, occasional paper series 78

Broner F, Didier T, Erce A, Schmukler SL (2013) Gross capital flows: dynamics and crises. J Monetary Econ Elsevier 60(1):113–133

Brukoff P, Rother B (2007) FDI may not be as stable as governments think. Magazine. International Monetary Fund Survey. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/survey/so/2007/RES051A.htm

Buch CM, Goldberg LS (2015) International banking and liquidity risk transmission: lessons from across countries. Int Monetary Fund Econ Rev 63(3)

Bussière M, Fratzscher M (2008) Financial openness and growth: short-run gain, long-run pain? Rev Int Econ 16(1):69–95

Cetorelli N, Goldberg L (2011) Global banks and international shock transmission: evidence from the crisis. Int Monetary Fund Econ Rev 9(1):41–76

Cetorelli N, Goldberg L (2012) Liquidity management of U.S. Global Banks: internal capital markets in the great recession. J Int Econ 88(2):299–311

Chor D, Manova K (2012) Off the cliff and back? Credit conditions and international trade during the global financial crisis. J Int Econ 87:117–133

Coeuré B (2015) Paradigm lost: rethinking international adjustments. Egon and Joan von Kashnitz Lecture, Clausen Center for International Business and Policy, Berkeley

Committee on the Global Financial System (CGFS) (2010) Funding patterns and liquidity management of internationally active banks. Committee on the Global Financial System Papers No 39

Committee on the Global Financial System (CGFS) (2011) Global liquidity—concept, measurement and policy implications. Committee on the Global Financial System Papers, 45

Converse N (2017) Uncertainty, capital flows and maturity mismatch. J Int Money Finance (forthcoming)

European Central Bank (ECB) (2016) Understanding the weakness in global trade—what is the new normal? European Central Bank, Occasional Paper Series 178

Erce A, Riera-Crichton D (2015) Catalytic IMF? A gross flows approach. European stability mechanism, working paper 9

Forbes K, Fratzscher M, Straub R (2015a) Capital-flow management measures: what are they good for? J Int Econ 96(S1):S76–S97

Forbes KJ, Reinhardt D, Wiedalek T (2015b) The spillovers, interactions, and (un)intended consequences of monetary and regulatory policies. In: 16th Jacques Polak annual research conference

Forbes KJ, Warnock FE (2012) Capital flow waves: surges, stops, flight, and retrenchment. J Int Econ 88(2):235–251

Fratzscher M (2011) Capital flows, push versus pull factors and the global financial crisis. J Int Econ 88(2):341–356

Gambacorta L, Van Rixtel A (2013) Structural bank regulation initiatives: approaches and implications. Bank for International Settlements, working papers No 412

Ghosh AR, Qureshi MS, Kim JI, Zalduendo J (2014) Surges. J Int Econ 92(2):266–285

Hale G, Obstfeld M (2014) The Euro and the geography of international debt flows. National bureau of economic research, working papers 20033

Hoekman B (2015) The global trade slowdown: a new normal? Centre for Economic Policy Research eBook. http://www.voxeu.org/content/global-trade-slowdown-new-normal. Accessed 24 June 2015

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2012) The liberalization and management of capital flows: an institutional view. http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2012/111412.pdf

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2015) Global financial stability report—navigating monetary policy challenges and managing risks. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC

Kaminsky G, Schmukler S (2003) Short-run pain, long-run gain: the effects of financial liberalization. National Bureau of Economic Research, working papers 9787

Levchenko AA, Mauro P (2007) Do some forms of financial flows help protect against ‘sudden stops’? World Bank Econ Rev 21(3):389–411

McQuade P, Schmitz M (2017) The great moderation in international capital flows: a global phenomenon? J Int Money Finance 73(A):188–212

Milesi-Ferretti GM, Tille C (2011) The great retrenchment: international capital flows during the global financial crisis. Econ Policy 66:28–346

Obstfeld M (2012) Does the current account still matter? Am Econ Rev 102(3):1–23

Ostry JD, Ghosh AR, Chamon M, Qureshi MS (2011) Capital controls: when and why? Int Monetary Fund Econ Rev 59:562–580

Ostry JD, Ghosh AR, Chamon M, Qureshi MS (2012) Tools for managing financial-stability risks from capital inflows. J Int Econ 88(2):407–421

Pasricha G, Falagiarda M, Bijsterbosch M, Aizenman J (2015) Domestic and multilateral effects of capital controls in emerging markets. Working Paper 2015-37

Puy D (2015) Mutual funds flows and the geography of contagion. J Int Money Finance 60(C):73–93

Reinhart C, Reinhart V (2009) Capital flow bonanzas: an encompassing view of the past and present. National Bureau of Economic Research Chapters, National Bureau of Economic Research International Seminar on Macroeconomics 2008, 9-62

Rey H (2013) Dilemma not trilemma: the global financial cycle and monetary policy independence. Jackson Hole Paper August 2013

Shin HS (2012) Global banking glut and loan risk premium. Int Monetary Fund Econ Rev 60(2):155–192

Tarullo D (2012) Regulation of foreign banking organizations. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Speech at the Yale School of Management Leaders Forum

Tarullo D (2014) Enhanced prudential standards for bank holding companies and foreign banking organizations. Opening Statement by Gov. Daniel K. Tarullo

Tille C, Van Wincoop E (2010) International capital flows. J Int Econ 80:157–175

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bussière, M., Schmidt, J., Valla, N. (2018). International Financial Flows in the New Normal: Key Patterns (and Why We Should Care). In: Ferrara, L., Hernando, I., Marconi, D. (eds) International Macroeconomics in the Wake of the Global Financial Crisis. Financial and Monetary Policy Studies, vol 46. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-79075-6_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-79075-6_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-79074-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-79075-6

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)