Abstract

The dual eligibles are low-income older adults and younger persons with significant disabilities who are enrolled in both the Medicare and Medicaid programs. This population depends heavily on the structure of healthcare financing, eligibility determination, and both federal and state funding. Changes in access and eligibility, and the disparity among states, could profoundly affect quality metrics and consequently the health of the dual-eligible population.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Scope of the Problem

The dual eligibles constitute the population of low-income older adults and younger persons with significant disabilities. All dual eligibles qualify for full Medicare benefits , but they differ in the amount of Medicaid benefits for which they are eligible. Approximately 88% are “full duals,” who qualify for full benefits from both programs. The other 22% are “partial duals,” who do not meet the eligibility requirements for full Medicaid benefits but qualify to have Medicaid pay some of the costs they incur under Medicare. Some 60% of dual eligibles are 65 years and older. [1]. Currently 10.4 million Medicare beneficiaries are also enrolled in the Medicaid program [2].

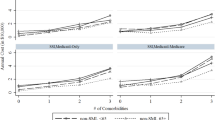

Of all the participants in Medicare and Medicaid, the dual-eligible population includes recipients who have the lowest incomes and highest chronic disease burden. Full duals as a group account for a disproportionate share of federal and state spending for Medicare and Medicaid . Full duals make up 13% of the combined population of Medicare enrollees and aged, blind, or disabled Medicaid enrollees (the categories of Medicaid participants who might also qualify for Medicare), but they account for 34% of the two programs’ total spending on those enrollees [4]. Additionally for Medicare, duals represent 18% of the Medicare population but 32% of Medicare expenditures. Some 58% report functional ability deficits. Average per capita Medicare spending on dual-eligible beneficiaries was twice that for non-dual-eligible beneficiaries in 2013 ($19,785 compared to $9035) and 9% of duals live in institutional settings compared to 4% of non-dual-eligible Medicare beneficiaries [2]. The dual-eligible population has a high proportion of high-cost chronic conditions compared to other populations (Fig. 9.1). The dual-eligible population is by any measure a high-risk, high-need population.

Mean number of chronic conditions among three groups of Massachusetts residents [3]

In practice, Medicare functions as the primary insurance for acute medical care, including hospital, physician, and diagnostic services. Medicaid helps fill in many of the gaps for dual-eligible beneficiaries for care not covered by Medicare. Medicaid covers out-of-pocket costs associated with Medicare such as monthly premiums and cost-sharing amounts. However, state Medicaid programs are not required to pay the full share of the Medicare cost-sharing amount. The largest gap that is filled by Medicaid is the coverage of long-term care services and supports, such as non-skilled nursing home care. These services are not covered by Medicare. Depending on their income and assets, dual-eligible beneficiaries may qualify for full or partial Medicaid coverage.

Medicaid is a state–federal partnership with policies driven at the state level through waivers and state plan amendments. To receive federal funding for Medicaid benefits, states must meet federal coverage standards, including covering designated populations like low-income older adults and providing a minimum set of covered benefits. The federal government provides matching funds to states for Medicaid funding. The matching rate ranges from 50% to about 75% across states depending on the state’s economic circumstances, with wealthier states receiving a lower federal matching rate. Currently federal funding to states is guaranteed and fluctuates depending on program needs.

Beyond meeting the minimum federal Medicaid coverage standards for receiving federal matching funds, states can also opt to provide additional Medicaid benefits, such as dental services, or to expand coverage to additional populations, such as older adults who require long-term care services and supports but whose income is too high to otherwise qualify for Medicaid. States can also vary in how they administer their Medicaid benefits, including the setting of provider payment rates and requiring beneficiaries to join Medicaid managed care plans.

Cost sharing and benefits are shifted between the two programs, impacting access to care and quality of care. For example, a dual-eligible beneficiary who lives in a nursing home may rely on Medicare to cover all acute medical costs, such as inpatient stays and rehabilitative services, but rely on Medicaid to cover the long-term residential costs of living in the nursing home. It is difficult to achieve an optimal level of care for this beneficiary unless each program coordinates these services. To improve the organization of care, federal and state governments, working with their local partners, need to coordinate and incentivize the provision of evidence-based social support services in conjunction with the delivery of medical services.

In recent years, participation in managed care plans has been increasing for dual-eligible beneficiaries. For their Medicare benefits , dual-eligible beneficiaries can elect to enroll in managed care plans that are offered through the Medicare Advantage Program. In 2014, 2.8 million dual-eligible beneficiaries belonged to Medicare managed care plans [4]. Indeed, Congress authorized a unique set of plans called Dual-Eligible Special Needs Plans in 2003 that can exclusively enroll dual-eligible beneficiaries. These plans may improve care delivery by providing enhanced benefits, including care coordination services. In contrast to traditional Medicare, though, managed care plans can also implement narrow or restricted provider networks and employ practices like prior authorization, which may limit their popularity with dual-eligible beneficiaries.

For the provision of Medicaid benefits , states can require their dual-eligible beneficiaries to enroll in managed care plans that administer Medicaid benefits, including long-term care services and supports. As of 2014, 17 states required that dual-eligible beneficiaries enroll in Medicaid managed care plans [4]. An additional 26 states gave dual-eligible beneficiaries the option of enrolling in a Medicaid managed care plan. As of 2013 there were some 272 Medicaid managed care organizations operating nationally [5].

Managed care plans have been viewed as a pathway for providing more integrated care delivery and for aligning financial incentives across Medicare and Medicaid to achieve better care coordination and quality of care. One such model is a voluntary integration approach where dual-eligible beneficiaries choose to enroll in a Medicaid managed care plan and a Medicare managed care plan operated by the same insurer. Although the beneficiary is enrolled in two separate plans, the insurer has a financial incentive to efficiently coordinate Medicaid and Medicare benefits. This minimizes regulatory duplication and differences between Medicare and Medicaid while streamlining processes such as enrollment and data reporting. A second approach, which is being tested by the federal government and select states, involves creating managed care plans that contract with Medicare and a state Medicaid program to provide Medicare and Medicaid benefits through a unified plan. These plans must achieve certain quality standards. Because these plans are paid on a capitated basis, they can financially benefit from any savings in providing improved quality and reduced cost for Medicare/Medicaid recipients [6].

Medicaid allows waivers for states to implement demonstration programs demonstrating value-based purchasing to improve service outcomes for duals. Many adults in the dual population have multiple illnesses that require intensive care coordination. Access to behavioral health remains limited in many communities however and functional limitations combined with limited transportation interfere with access producing challenges to obtaining quality care for many duals.

Low reimbursement rates may make it difficult to attract managed care organizations to participate in capitated dual-eligible demonstrations. A Federal Coordinated Healthcare Office (FCHCO) has been developed to assist duals in obtaining access to entitled services, to simplify enrollment processes for long-term care and social support services, and to encourage improved provider performance under the Medicare and Medicaid programs.

Provision of care to the dual-eligible population depends heavily on the structure of healthcare financing, determinations of eligibility, and both federal and state funding. Thus these programs are at risk depending on political considerations. Changes in access and eligibility and any resultant disparity among states could profoundly affect quality metrics and consequently the health of the dual-eligible population. Medicaid consumes a growing share of state budgets as the number of enrollees grows. As much as 70% of program resources are devoted to individuals with disabilities living in institutional settings. An interactive site displaying data for each state Medicaid program in summary fashion is available at the Kaiser Family Foundation website [7].

The cost of home services is low for individuals requiring basic care but as added services are imported into the home the cost could easily exceed the cost of nursing home care. Some states use a needs assessment tied to functional abilities and may restrict home- and community-based services, possibly forcing some individuals into long-term care facilities. For example, Tennessee’s Medicaid program requires functional disability equivalent to nursing home admission criteria, but limits care at home to less than the cost of nursing home care [8].

Medicaid has been an open-ended entitlement program extremely popular with beneficiaries and the general public [9]. Subject to program rules, states can receive matching funds on their Medicaid spending without limit. Changes in Medicaid funding including Medicaid block grants, whether capitated or fixed, could give states more flexibility, but also put them at risk for covering increasing healthcare costs. States could respond and severely limit Medicaid services. Less funding could be available for mental health services and home and community-based care. Block grants could also lock in historical differences between states increasing disparities and reducing reimbursement to providers including physicians, hospitals, and long-term care facilities, thus further reducing access for vulnerable populations.

There are calls to reform Medicaid to help improve enrollment and coordination [10] and to provide outcome-based core program metrics [11]. Outcome metrics could help guide Medicaid program quality and balance resource allocation decisions.

References

Congressional Budget Office. Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries of Medicare and Medicaid: Characteristics, Health Care Spending, and Evolving Policies. https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/113th-congress-2013-2014/reports/44308dualeligibles2.pdf. Accessed 17 Nov 2017.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Data book: Beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid —June 2017 MedPAC | MACPAC. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/data-book/jun17_databookentirereport_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed 17 Nov 2017.

National Academy of Medicine. Effective care for high need patients: opportunities for improving outcomes, value, and health. Ch 2. Key characteristics of high need patients. https://nam.edu/initiatives/clinician-resilience-and-well-being/effective-care-for-high-need-patients/. Accessed 17 Nov 2017.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS Program Statistics, 2014 Medicare enrollment section https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/CMSProgramStatistics/2014/2014_Enrollment.html. Accessed 17 Nov 2017.

Ndumeie CD, Schpero WL, Schlesinger MJ, Trivedi AN. Association between health plan exit from Medicaid managed care and quality of care, 2006–2014. JAMA. 2017;317:524–2531.

Warshaw G, DeGolia PA. Medicare and medicaid coordination: special case of the dual eligible beneficiaries. In: Powers JS, editor. Healthcare changes and the affordable care act. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2015. p. 117–32.

Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid state fact sheets http://kff.org/interactive/medicaid-state-fact-sheets/. Accessed 17 Nov 2017.

TennCare Choices program eligibility sheet. https://www.tn.gov/tenncare/article/to-qualify-for-choices. Accessed 17 Nov 2017.

Inglehart JK, Sommers BD. Medicaid at 50: from welfare program to nations largest health insurer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2152–9.

Branch E, Bella M. What is the focus of the integrated care initiatives aimed at Medicare-Medicaid beneficiaries? J Amer Soc Aging. 2013;37:6–12.

Slavitt A, Wilensky G. JAMA forum: reforming Medicaid. JAMA. 2017;318:601–2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Powers, J.S., Keohane, L.M. (2018). Dual Eligibles: Challenges for Medicare and Medicaid Coordination. In: Value Driven Healthcare and Geriatric Medicine. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77057-4_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77057-4_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-77056-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-77057-4

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)