Abstract

This chapter discusses the article “The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms” by Danny Miller (Manag Sci 29(7):770–791, 1983). This is considered a foundational article because of how deeply it has impacted the field of entrepreneurship. First, it is the inspiration for the concept of entrepreneurial orientation (EO). It provided the idea that the construct of innovativeness, proactiveness and risk-taking influence greatly how a firm acts in its context. Second, it afforded researchers with a scale to study entrepreneurship within larger and older organizations. Thus, it effectively shed some light on corporate entrepreneurship (CE). I discuss how it impacted the field in its early years and how it still does in the latter years. I integrate the current work in the field to suggest future researches.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Entrepreneurial

- Orientation

- Corporate

- Configurational

- Risk-taking

- Innovativeness

- Proactiveness

- Growth

- Performance

Introduction

As Danny Miller ironically mentioned , “when I attended a local conference in 2004, an article on EO was being presented. […] I asked, ‘What does EO stand for?’ The incredulous speaker responded, ‘You’re kidding, right?’ I was not. [I] never used the term EO [in the 1983 article]” (Miller 2011; p. 873). Although, incidentally, his 1983 article has impacted the field of entrepreneurship in quite an important manner as well as the very definition of entrepreneurial orientation (EO). Miller’s paper inspired the concept of EO, representing an important leap for research in entrepreneurship as previous work had mainly focused on the individual characteristics of the entrepreneur . Subsequent work on EO and new ventures thus put the emphasis on characteristics of the firm and what makes them entrepreneurial. In this regard, it shed some light on the behaviors and attitudes of a firm that would make it more or less entrepreneurial.

Amazingly, although the article has been cited over 4000 times, it had only 62 citations in the ten years following its publication. This can be attributed to the fact that the EO construct was not the main message within the article and that it does not immediately come to mind at first read. However, with the seminal works of Covin and Slevin (1989, 1991) and Lumpkin and Dess (1996), who formulated the construct of EO based on the dimensions proposed by Miller (1983), EO has consistently been in discussion as demonstrated by the number of citations over the years with more than 100 per year since 2005. This is a sign that, rather than slowing down, the notion of EO is instead picking up steam. As such this paper has recorded its highest number of citations in 2016 with 550 and both in 2013 and in 2015 with 427. Figure 4.1 shows the evolution of citations on a yearly basis. In a way, it demonstrates that this paper still exercises its influence even after 30 years. What has helped its relevance is the fact that so many scholars were interested in the phenomenon and it broached many different research topics related to entrepreneurship.

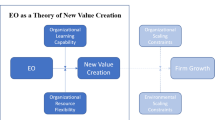

Two main outcomes from the article can be identified. First, as already mentioned, the construct of EO and its components, proactiveness , innovativeness and risk-taking have been widely investigated by entrepreneurship scholars. Second, and in a way related to EO, was how the study of corporate entrepreneurship (CE) was facilitated. With EO and scales measuring it, scholars were afforded with a means to measure the entrepreneurial capability of firms and to show how this affects their performance . As such, EO provides a perspective on the relation between organizations and new ventures, no matter their size or stage (Miller 2011).

The present chapter is organized as follows: first, we present a summary of the article. Second, we discuss how the concept of EO evolved from Miller (1983) in its early days. We look at the two topics of research in EO that were most interesting and prompted the most enquiries: firm performance and CE while also looking at an underexplored topic in the configurational approach . Third, in an interesting revisit of his 1983 article, Miller (2011) discusses the concept of EO, how it has evolved and where research was heading. It provides a perspective of how the author perceived the evolution of the construct. Fourth, we explore how the concept of EO has evolved 30 years after the introduction of its dimensions and the Miller (1983) article. An overview of the research field provides four topics related to EO that show potential: the evolution of the measurement of EO, firm growth , family firms and internationalization. Each of these topics extends the concept of EO. Finally, we conclude with a synthesis of how the Miller (1983) article has helped the entrepreneurial field and what effectively makes it a foundational article.

The Correlates of Entrepreneurship in Three Types of Firms

In this article, Miller (1983) discusses how different configurations of firms are associated with different ways of organizing and different types of behaviors. He proposes three types of firms inspired by Mintzberg (1973, 1979): Simple, Planning and Organic. The Simple firm is characterized by a smaller size, operating in a homogeneous environment, centralized structure and implicit reliance in the leaders. In this type of organization, how entrepreneurial the firm is would reflect the owner(s)/manager(s). The Planning firm is characterized by a larger size, in a stable environment, with centralized structure and reliance to control and planning systems. Efficiency is privileged in this type of firm. Entrepreneurship would be much related to the firm’s strategy and would follow a systematic process of innovation . The Organic firm is characterized by different organizational sizes, a complex environment, a decentralized structure with delegation of authority and reliance to a flexible and adaptive planning. The complexity and hostility of the environment could dictate how entrepreneurial the firm would be.

In considering these firms, he discusses three characteristics that relate to entrepreneurship: innovativeness , proactiveness and risk-taking. He describes an entrepreneurial firm as:

One that engages in product-market innovation , undertakes somewhat risky ventures, and is first to come up with “proactive” innovations , beating competitors to the punch. A nonentrepreneurial firm is one that innovates very little, is highly risk averse, and imitates the moves of competitors instead of leading the way. We can tentatively view entrepreneurship as a composite weighting of these three variables. (Miller 1983; p. 771)

This last sentence seems to lie at the foundation of what came to be known as EO. Although he never mentions the words “Entrepreneurial Orientation” in his article, the concept is described clearly.

Another major contribution to the field of entrepreneurship is the focus on the firm as the unit of analysis as opposed to the entrepreneur as an individual. As such, it has effectively opened the door to the study of entrepreneurial actions within larger organizations , CE. Taken together, EO and CE allow scholars to study how all firms, not just start-ups, are able to innovate and start new ventures. It is not just the creation of new firms but also innovative projects by a firm’s subunit.

By presenting three types of firms with very different characteristics and looking at how entrepreneurial they are, this article considers how different firm configurations might present distinct patterns of entrepreneurial actions. In a configurational approach, the setup of the firm, its environment, its context and its strategies are interrelated to dictate how entrepreneurial the firm would act.

Early Influence of Entrepreneurial Orientation Research

Considering the importance of EO within entrepreneurial research, it is a wonder why it took such a long time for the concept to pick up steam. Two articles helped bring EO to prominence: “Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments” by Covin and Slevin (1989) and “Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance” by Lumpkin and Dess (1996). Both are further discussed in other chapters so they are only summarily discussed in how they relate to Miller (1983). First, Covin and Slevin (1989) build on Miller (1983) to highlight how the environmental context might favor or harm different types of strategic management practices. They show that the structure and strategy adopted by firms affect how they can answer the specific demands of their industry. Meanwhile, Lumpkin and Dess (1996) extend the three dimensions of EO (proactiveness , innovativeness and risk-making) previously introduced by Miller (1983) with two additional dimensions (competitive aggressiveness and autonomy). They suggest that EO could act as an indicator of the entrepreneurship process by firms.

The early days of building up the concept of EO has played a significant role in the perception of how firms grow and survive. It provides a firm-level perspective that helped understand how organizations develop an entrepreneurial mindset and culture.

EO and Firm Performance

While Lumpkin and Dess (1996) were the first to discuss performance related to EO, research has subsequently picked up on how EO influences a firm performance. Wiklund and Shepherd (2005) highlight how performance can be measured through different ways such as growth , profit and cash flow. For their study, they use a measure of the perceived level of satisfaction for the access to financial capital. The respondents mostly self-reported on some subjective indicators such as “better or worse” than competitors. This indicates that EO really depicts how firms evolve and how it influences not only performance but how it is measured.

Rauch, Wiklund, Lumpkin and Frese (2009) published a meta-analysis on EO. They find a distinction between financial and nonfinancial measures. Sales and return on investments (ROIs) are the primary financial measures. Meanwhile, satisfaction and global success ratings are the primary nonfinancial measures. They also observe that most studies relied on performance self-assessment. They conclude that EO is related to performance.

In regard to performance, the influence of Miller (1983) can be easily detected. When discussing Simple, Planning and Organic forms of the firm, he concludes that the relation between the structure and the strategy of those firms provides them with a positioning toward entrepreneurial activities. In this instance, how each different type of firm chooses to pursue its activities plays a role directly on its performance.

Corporate Entrepreneurship

Miller (1983) was among the first papers to discuss entrepreneurship at a firm level rather than an individual level. EO provides a perspective of how different components of a firm would make it more or less entrepreneurial and how it plays a role in the firm’s continual survival and growth.

CE can be described in different ways. Covin and Miles (1999) provide three of the most common situations in which it takes effect:

(1) an “established” organization enters a new business; (2) an individual or individuals champion new product ideas within a corporate context; and (3) an “entrepreneurial” philosophy permeates an entire organization’s outlook and operations. These phenomena are not inherently alternative (i.e. mutually exclusive) constructs, but may co-exist as separate dimensions of entrepreneurial activity within a single organization. (p. 48)

Covin and Slevin (1991) highlighted the growing interest in CE. They discuss the development of the entrepreneurial process and how it evolved into including firm-level characteristics and how it can be measured through a firm’s performance . They pursue the idea put forth by Miller (1983) and Burgelman (1984) that entrepreneurship can be a firm-level phenomenon. They build on the idea that, depending on the structure of the firm, individual-level and organizational-level characteristics can overlap but would diverge as the size of the firm increases and its structure changes.

Zahra and Covin (1995) define their concept of CE from Miller’s (1983) perception of a firm’s commitment to innovation and how it links to EO. They equate CE to the components of EO. In that sense, they indicate that CE represents a firm’s willingness, “to engage in business ventures or strategies in which the outcome may be highly uncertain. Together, product innovation , proactiveness , and risk-taking capture the essence of CE” (Zahra and Covin 1995; p. 45). They also highlight how it relates to the firm’s financial performance . They suggest that CE would be a long-term commitment by the firm and is embedded in their organizational culture. It would be greatly influenced by their environment.

Barringer and Bluedorn (1999) define CE as behavioral phenomena. They argue that “all firms fall along a conceptual continuum that ranges from highly conservative to highly entrepreneurial. Entrepreneurial firms are risk-taking , innovative, and proactive” (p. 422). They suggest that entrepreneurial firms include extensive scanning, short-term planning and flexibility.

Covin and Miles (1999) studied CE and correlate it to the components of EO as introduced by Miller (1983): innovativeness , proactiveness and risk-taking . They argue that the study of EO should be related to firm performance or competitiveness. CE follows the same pattern with an emphasis on the increase of competitiveness. It seeks to observe the rejuvenation, reinvigoration and reinvention of firms. EO would influence directly how firms would enact their entrepreneurial spirit. As such, CE could be situated within a continuum of EO. It would span from organizational rejuvenation all the way to domain redefinition. EO would then be a marker of what firms might do in order to achieve competitive advantage and how it relates to the firm’s strength and its industry context.

The study of CE has implications for how firms can sustain growth over time and how they can maintain their advantage. Miller’s (1983) paper provided the impetus to develop CE. The components of EO, as introduced in the paper, play a role in CE. They influence how a firm acts and how it can position itself within its industry.

Configurational Approach

An important theme of Miller (1983) that has mostly been underappreciated is the configurational approach. By separating into Simple, Planning and Organic firms with different levels of innovativeness , risk-taking and proactiveness , there is an emphasis on how distinct configurations influence the way firms operate. The focus of the firm and its personality are important determinants of how entrepreneurial a firm is. The configuration also would dictate how the firm works with its environment and how the different correlates are influenced by it.

Wiklund and Shepherd (2005) describe how increased comprehension of firm-related phenomena like performance and growth can be attained by better understanding how firms share some commonalities. The further exploration of how certain attributes span across firms would identify why those firms share those attributes. Configurations display how certain aspects of a firm are complementary and would thus be present within different firms. Within a configurational logic, a firm’s structure, its different attributes and its interaction with its environment affect its performance and its positioning toward its competitors. As such, there could be an isomorphism of configurations as firms that adequately match their configurations to their structure would show better odds of surviving. Ultimately, there would be a congruence of configurations depending on the structure of a firm. Therefore, the study of EO would be most appropriate following a configurational approach.

Miller Revisited (2011)

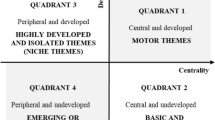

In an interesting evolution to his 1983 article, Miller (2011) wrote a paper to assess how the concept of EO has been studied by other scholars. With almost 30 years between the two articles, there were many opportunities to sit back and reflect on what had been achieved. In reviewing the different directions in which research has gone, he provides an overview of how EO has attracted scholars into a multitude of themes such as environmental and organizational factors, strategic context, organizational resources and performances.

Within the paper, Miller (2011) highlights the evolution of EO into a process. He also discusses how the different components of EO have been perceived by other researchers. As such, from the original components of proactiveness , innovativeness and risk-taking , some studies add competitive aggressiveness and autonomy. He also describes a broadening of the scope of study of the EO construct. This is represented by the interest in the antecedents of EO and its effect on firm performance . Finally, he points toward the sophistication of methodology and measurements related to EO.

An important part of this paper is Miller’s suggestions on how to improve on EO research and what scholars can focus on in the future. He highlights a few weaknesses of EO research and how to improve on them. He pleads for researchers to investigate EO on a deeper level and a more cumulative knowledge. He argues that there are too few quality qualitative studies and that the scales used in evaluating EO have been the same for most studies. It has led to a restraint in the operationalization of the EO construct. He also adds that longitudinal studies such as panel data research and event history studies would improve the knowledge of how EO emerges and evolves over time.

In order to further the knowledge on EO, Miller recommends a few directions for researchers to investigate. He suggests alternative operationalizations of the EO construct, most specifically different measures and instruments. He argues for a separation of the aspects of EO into attitudinal and behavioral ones. This could effectively provide a clear scheme of research for scholars. On the one hand, attitudinal aspects would be reflected through qualitative methodologies such as interviews and observations to better understand their conceptions of EO and how it impacts their vision of their organizations. On the other hand, behavioral aspects would be measured with quantitative methodologies such as secondary data like investments and sales to better understand how they act based on each component of EO.

He highlights how EO research might benefit from a clearer clarification of the different types of entrepreneurial initiatives. He discusses how a variety of new entries exists depending on the circumstances of the firm. He distinguishes how start-ups, high-tech venturing and intrapreneurship might be studied differently. By looking at new entries at both different levels of analysis and at different periods of organizations, it could effectively uncover new variables of EO. By attaining a higher degree of specificity customized to different types of firms, EO indicators might provide a better assessment of their entrepreneurial process. Miller additionally advocates for further precision by disaggregating the components of EO and studying them specifically within the particular context of organizations. He suggests that each component could potentially impact the organization differently at discrete instances in its lifecycle. It also brings to mind that each different component could impact organizational indicators such as performance or growth.

Miller argues for both more fine-grained research into the context of firms and linking EO to current theories. He highlights how the precise circumstances and environment of an organization affect how it operates. Thus, studies within specific industries, specific regions and following specific events would add to the knowledge on EO. In addition, he contends that theories such as agency theory, resource-based theory and the dynamic capabilities have contributed to better study the construct of EO but that further endeavors within organizational theories would enhance EO research in the future.

Finally, Miller advocates for the configurational approach. In what arguably is the core of this paper, he insists that it could be integral to the study of EO. Returning to Miller (1983) and incorporating some of the previous elements from the 2011 paper, he reiterates the importance of the context of organizations and how they compare to each other. As such, he argues that understanding theoretical typologies and empirical taxonomies gives a perspective to how EO is enacted. He goes further in reasoning that how theories are applied to study EO could be impacted by the type of industry, environment or context. His example is that institutional logics might dictate that EO would impede law firms while enhancing consultancy firms.

Miller provides a fair assessment of the status of research on EO and how it has evolved since the early years of the introduction of the construct. As such, while Miller (1983) acts as the catalyst in introducing EO to entrepreneurship scholars, Miller (2011) would serve as a guide to better understanding it and to expand its reach. First off, by reintroducing the different dimensions of EO and the configurational approach , he efficiently summarizes his 1983 paper. Second, his recommendations of following EO as a process and of diversifying the methods to study are given. This is particularly relevant as it could influence how future scholars can approach research on EO. A more qualitative methodology with in-depth studies and a process perspective effectively create a whole new dimension to research in EO. Finally, his suggestions of domains of enquiry serve as a bridge to other fields. This would effectively allow to broaden the scope of research of EO. As such, Miller (2011), as a complement to Miller (1983), plays a critical role in the EO literature since the two taken together help define the field.

Contemporary Research on the EO Construct

As Miller (2011) advocated, recent studies on EO have evolved and helped the construct progress. The EO construct has been maintaining the interest of scholars since the early 1990s but it has garnered additional attention since 2011. As such, more than three decades after it was published, Miller (1983) has been cited 437 times in 2013, 425 times in 2014, 437 times in 2015 and 550 times in 2016.

The topics presented in the following section include some contemporary researches that help the progression of the EO construct. They are influenced by Miller (1983) and build from the recommendations from Miller (2011) to broaden the research scope on EO.

EO Measurement

A topic that has been discussed since the Miller (1983) paper is how to measure EO. As mentioned earlier, the dependent variable usually hinges on performance , whether financial or nonfinancial. As Miller (2011) expressed, a more difficult task has been to measure the determinants of EO and their relation with performance . As such, scholars have tried to both expand and organize how the determinants of EO can be measured.

Covin and Wales (2012) discussed how these measures can be divided into two different types: formative and reflective. Formative measures are independent among themselves. In that regard, they recommend examining their external validity. Reflective measures are correlated between themselves and would lean toward the same direction. They recommend examining their correlation and internal consistency. They posit that EO can effectively be measured through both types of measures depending on the model selected for research. They present four different models that can be measured differently: the Miller/Covin and Slevin, an alternative first-order reflective EO scale, the Hughes and Morgan EO scale and a “Type II” second-order formative EO scale. They conclude that each model measures a different phenomenon of EO.

Anderson, Kreiser, Kuratko, Hornsby and Eshima (2015) proposed a different approach to EO and to its measurement. They suggest an EO model of entrepreneurial behaviors and managerial attitude toward risk. They took the three components from Miller (1983) and associated with the two dimensions. Proactiveness and innovativeness would be related to entrepreneurial behaviors and risk-taking would be related to managerial attitude toward risk. Within this approach, the components would require formative measures. Meanwhile, the two dimensions would be measured in a reflective way as they relate to EO. Their reconceptualization of EO opens the door to future research and to the broadening of the concept.

EO and Firm Growth

Miller (2011) argued that the determinants of EO would have different effects based on the configuration of firms. As such, growth might be related to the context, the structure and the environment of the firm. EO might be particularly salient to young firms as well as older firms that seek to avoid stalling. Scholars studying the EO-growth relationship examine how EO influences the growth of the firm based on different factors such as firm age, scarcity of resources and strategic posture.

Anderson and Eshima (2013) discuss how growth becomes more difficult for older firms. They argue that organizational routines can hinder the process of their growth. They can limit their adaptability, decrease their market responsiveness and provide them with outdated market knowledge. They posit that as firms age and accumulate intangible resources, EO has a lowered effect. However, they also find that those intangible resources, by themselves, are an important source of growth for new ventures. EO and intangible resources are correlated and interact to provide growth. As such, while EO plays a role in the growth of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), it becomes much more complicated for older firms. Since EO is a strategic posture that consumes large quantities of resources, it requires a commitment from the firm. Furthermore, with EO being associated with a renewal of the organization and its resources, a path dependency based on intangible resources could prevent effective growth within older organizations. And so, intangibles that are so important for young ventures could become limitations to older firms. EO thus needs to be studied differently for younger firms than it would be for older firms.

Eggers, Kraus, Hughes, Laraway and Snycerski (2013) discuss SME growth and the impact of EO and customer orientation (CO) on it. They argue that the scarcity of resources for SME might preclude them from following both postures. They determine that EO is a driver of growth because it puts a focus on innovation that will bring a renewal of the firm. On the other hand, CO focuses on the immediate and how to satisfy the current needs of customers. In the case of SME, scarcity of resources would lead them to concentrate on generating immediate revenues. They are thus posturing toward CO and the gathering of financial resources. However, they find that the highest growth rate among SMEs is achieved through a high EO coupled with a low CO. As such, they do not see EO as a continuous trait of growing and performing firms but that, rather, it is fluctuating between high EO/low CO and low EO/high CO to balance successful growth strategies.

Lechner and Gudmundsson (2014) discuss how EO relates to not only growth but also survival of the firm. They find that the different dimensions of EO have different impacts on survival. As such, innovativeness correlates positively while risk-taking and competitive aggressiveness correlate negatively. So, although EO can help firms grow, it can also become a hindrance to their survival if its dimensions such as risk-taking and competitive aggressiveness reach high levels. Also, they compare how different types of strategies relate to EO and how they influence growth. They find that EO has a positive association with differentiation and a negative one with cost leadership when it comes to firm growth. It is linked to characteristics that are related to both EO and differentiation such as speed and flexibility. On the other hand, cost leadership is related to routine and uniformity.

McKinley, Latham and Braun (2014) discuss how EO plays a role, both positively and negatively, in the decline and turnarounds of firms. They propose that EO can provide a turnaround when a declining organization stimulates innovation that helps to reverse their decline. This requires that those innovations be flexible. On the other hand, if the innovation produced is rigid, it could lead to further decline. As such, innovativeness can help the survival and growth of firms, even those that are going through a decline. However, other dimensions of EO would play a role in the effect of innovativeness on decline and turnarounds. Proactiveness would help firms to not be locked into a rigid innovation while risk-taking would be the impetus to use the innovation to turn around the decline. Eshima and Anderson (2016) discuss how adaptive capability relates to EO for the growth of the firm. They argue that fast-growing firms are faced with a changing market. As such, adaptability has to increase to cope with it. It affords the firm with increased resources and the possibilities of resource combinations. In this regard, since EO is a resource-consuming strategic posture, increased adaptive capabilities would be correlated with EO. Furthermore, adaptive capabilities might be related to uncertainties coming from exploiting opportunities. As they do so, they might be required to adapt quickly. In the same sense, opportunity uncertainties are better coped with by firms through EO.

The components of EO as originally introduced by Miller (1983) showed that firms grow differently based on the way they are configured. He discussed how the three types of firms studied operated differently. It displayed that they not only had a different orientation but also demanded a totally different setup. As such, the different concepts discussed such as intangible resources, CO and adaptive capabilities affect the growth of firms differently as they interact with the way their EO is enacted.

EO and Family Firms

A topic that has gained steam in EO research is its impact on family firms. They have characteristics that make their studies compelling from an EO perspective. Miller (2011) suggested that the configurational approach might be integral to EO research. As such, a family firm can be configured in many ways with their own internal factors that influence how EO would be enacted. Scholars studying EO within family business answer calls to investigate different contexts related to family firms, how each determinant of EO acts differently within family firms and how longitudinal studies of EO within transgenerational firms could provide deeper knowledge.

Kellermanns, Eddleston, Sarathy and Murphy (2012) discuss how innovativeness is enacted in family firms. They highlight three characteristics of the family influence: how the family gets involved in the management, how dispersed the generational ownership is and the reciprocity of the family members. The way a family firm behaves can be explained in great part by how much the family is involved in the firm management. Furthermore, the maintenance of the family control over generations is a main feature of family firms.

In an EO fashion, the development of long-term goals and strategies by family members could lead to high performance by family firms. In opposition to non-family firms, family firms add a level of complexity as the firm grows. They have a generational layer that has a potential for discord. Relationships are not managed in the same manner either. Family firms generally start with more goodwill and altruism but these characteristics might erode over time. As more family members get involved and generations overlap, family ties and commitment to the firm might loosen. Another characteristic of family firms is the desire of their members to put aside their interests for that of the business. As such, they are more willing to assist each other and share responsibilities. This plays a role into how these firms can renew themselves and how they innovate.

Family members greatly influence the EO of family firms. In that regard, there is some complexity in how it is enacted, since family firms serve two different interests: that of the business and of the family. When these interests converge, then EO-related posturing can be achieved in the same manner as in non-family firms. However, when these interests diverge, the way EO is performed could be complicated. In such an instance, innovativeness and its perceived value to the firm could be the result of internal strife and would thus evolve in the same manner as family-member involvement increases. Therefore, family firms would likely experience stagnancy and slowly lose market shares. However, for families that embrace an EO posture, it would seem that their firms benefited from it than non-family firms. As opposed to generational decline, a clear entrepreneurial strategic positioning and organizational culture would effectively turn current family members and incoming generations into assets to the firm. With a clear and united vision, family members can work together to help with the identification of the opportunities and threats of the firm.

While EO has an impact on the continual growth of organizations, it might play an even bigger role in family firms. Because of the unique features of the family firm, a clearly defined entrepreneurial posture will enhance the relationship among family members and provide a direction for incoming generations.

T. Zellweger and Sieger (2012) discuss EO within family firms. They evaluate how each of its dimensions interacts differently as opposed to non-family firms. They argue that the dimensions of autonomy, proactiveness and innovativeness are related to their long-term performance . However, the perspective on performance and the dimensions of EO for family firms might be based on different points of reference. To protect the interests of the family, family firms might make decisions that would go against their performance . Autonomy is a driver of entrepreneurial activity because it empowers members of the firm. They find that it decreases as the firm grows. Each new generation would reduce the control in the hands of families. The latter generations would become less involved. And thus, the professionalization and involvement of managers outside the family reduce the internal autonomy of the family firm. They find that proactiveness is enacted in a particular manner within family firms. It exhibits a pattern that fluctuates over time. There would be low proactiveness most of the time with specific periods of high proactiveness . As such, the general attitude would be one of lying low until the right moment at which they would take carefully planned initiatives. However, they find that the structure of family firms might be a hindrance to proactiveness.

One particularity of family firms is the possibility of non-active family members owning parts of the firm. Since they are not involved in firm operations, they adopt a safer posture to protect their assets. As for innovativeness , there is also a particularity associated with family firms. There seems to be a preference for internal innovations as opposed to external innovations . This is explained by members of the family looking to build for the future. They aim to develop organizational system or structure rather than look for new products. As such, they focus on building internal capabilities before moving on to product innovation and inventions. The impact of EO on family firms, particularly as it pertains to crossing generations, might be of a dynamic nature. It might not be beneficial for them to try to attain the maximum level on all levels of EO. Rather, it would seem that it needs to be constantly adjusted to the situation of the firm. Also, it might seem that EO would be impacted strongly by changes in generation.

T.M. Zellweger, Nason and Nordqvist (2012) discuss how the particularities of family firms provide them with certain specificities in terms of EO. They compare it to a family orientation with the following dimensions: loyalty, security, stability and tradition. They also examine transgenerational entrepreneurship which is defined as the entrepreneurial mindset to renew the firms through generations. They highlight how those firms are confronted with a paradox of continuity for the family and change for the business. They suggest a concept called family entrepreneurial orientation (FEO) that they define as the family’s attitudes toward entrepreneurship. A unique specificity of family firms is their divestment and rearrangement in their business portfolio between generations. This is reflected in FEO where the EO of the firm is not seen uniquely in terms of its own growth but also the growth of the family’s wealth. In this instance, the dimensions of EO related to firm performance would need to be balanced with the dimensions of family orientation . These dimensions would take into account the interest of the family while covering entrepreneurial attitudes. They suggest that FEO focuses on value creation through generations by accommodating both the family and the business.

Eddleston, Kellermanns, Floyd, Crittenden and Crittenden (2013) discuss how generational differences affect the growth of family firms and how dimensions of EO would play a role in it. They find that strategic planning and succession planning help family firms grow but at different stages of their lifecycle depending on the generation in charge. Strategic and succession planning are a reflection of the firm’s engagement to its growth and how well it is communicated to members of the family as well as non-family members of the organization. It is required in order to keep family firms entrepreneurial. This is brought on by the fact that changes in generation bring different types of posture to the firm. First-generation members are the ones finding and exploiting an opportunity. The founder’s traits are embedded within the firm and its orientation is usually directed by them. EO is not usually overly present within the second generation because of its dynamics. It is created by conflicts among siblings. As such, decisions about firm development are more difficult to make because of a lack of consensus. With the third generation, an increase on EO might occur. This could be because of an increase in professionalization. With less strife and more non-family managers, there is more opportunity to make decisions about growth opportunities. However, with an increase of passive shareholders composed of family members, they might have a short-term perspective and seek dividends over long-term planning. As such, there are elements playing against EO and the growth of firms at each different generation. First generation might have some blindness related to their beliefs in themselves and in what they perceived as a successful strategy. Second generation might be slowed down by conflicts among siblings. Finally, third generation and later generations have a more fragmented ownership and passive family members. This slows decision-making and puts up barriers to growth . EO would be enacted differently with each generation of the firm because of their idiosyncratic nature. The study of EO within family firms would be required to take that into account.

Boling, Pieper and Covin (2015) discuss how the tenure of CEOs in family firms plays a role in their EO. They address how short-tenure and long-tenure CEOs have a negative effect on EO. They find, however, that this inverse u-shaped relationship is tampered in family firms. Because of the nature of family firms, CEOs that are family members do not have as much pressure to perform and have the freedom to follow an EO posture.

Miller (1983) showed the importance of the configurational approach because it shows how each type of firm acts differently. In doing so, it put forward EO and its dimensions . Family firms add a layer of component within the configurational approach with their different characteristics. Furthermore, EO has a distinct impact on family firms and is enacted in a separate manner. Because of generational disparities, EO and its dimensions are represented differently at discrete stages in their life.

EO Internationalization

Miller (2011) argues that the location of firms would have an influence on EO research. The internationalization of firms would serve as a proper field of study for EO scholars. The different dimensions of EO would interact in a divergent manner with firms that are in the process of internationalization or that are already in multiple countries.

Brouthers, Nakos and Dimitratos (2015) discuss how firm internationalization is facilitated by higher EO. They argue that it is provided through alliances with foreign market partners. As such, high EO firms gain more from these alliances because they possess the necessary capabilities and mindset to exploit resources from these external sources. They highlight innovations in marketing and technology as the two primary benefits of international alliances. This is mainly because of their willingness to innovate, their proactiveness in doing so and their ease with the risk that comes from changes to their currently used technology or their marketing process. While there is a higher cost associated with adapting to their targeted foreign market, it can provide them more legitimacy within that market. By matching with the demands of the consumers’ base, these firms enhance their probability of success in the new market. Finally, they find that higher EO provides firms with a better posture in the identification and pursuit of opportunities in foreign markets.

Covin and Miller (2014) review international entrepreneurial orientation (IEO). They suggest that it has been both discussed within the construct of EO and within the construct of international entrepreneurship (IE). They cite McDougall and Oviatt (2000) in defining IE: “a combination of innovative, proactive and risk-seeking behavior that crosses national borders and is intended to create value in organizations” (p. 903). It can thus be perceived as being quite close to EO. This would include a global orientation to the dimensions of EO. As such, the mindset of global organizations would both be entrepreneurial and international. They discuss how international performance is related to IEO. Most studies reviewed indicate that there is a positive impact of IEO on those international ventures. Proactiveness has been highlighted as being the better indicator for how firms perform in the international arena. One way through which it is achieved is by positively affecting the speed of internalization. It would be achieved through the amount of foreign market knowledge they can acquire. A factor that could play a significant role in how performance is achieved through IEO is the IT capability of the firm. They suggest that IEO might not only be at the juncture of EO and IE but that there might exist some dimensions that are not recognized or discussed. It makes IEO an interesting domain of research.

IEO is an interesting construct at the juncture or EO and IEO. It might as well possess its own characteristics and dimensions. Following Miller (1983), it becomes an extension of the three dimensions presented of proactiveness , innovativeness and risk-taking . As such, they play an important role in how firms internationalize but there is an addition related to the types and configuration of firms. Firms that are seeking to internationalize are entrepreneurial in nature but they also have an additional dimension related to culture. As such, IEO could be a significant research stream in future.

Conclusion

The article presented in this chapter is an example of how some of the work carried out in the 1980s has been invaluable to the development of the research in entrepreneurship. Its influence on entrepreneurship research has been twofold. First, the introduction of the EO concept has provided ample opportunities for scholars to develop research projects that enhanced knowledge on a variety of themes in entrepreneurship. It has broached into research domains such as international entrepreneurship, family business, knowledge transfer, market orientation , CO, learning orientation and top management team (TMT). It highlights how EO is deeply embedded within the domain of entrepreneurship. In allowing future research on such a variety of topics, this article has influenced the shape of the field in the past 30 years. Second, this article has provided an opportunity for scholars to explore the phenomenon of CE . While there were prior studies on how firms innovate, this article has offered a link to the behaviors and attitude of a firm with how entrepreneurial they are. The study of different types of firms and of different configurations allowed to observe a difference in how those firms acted and their characteristics in their specific context. In doing so, it afforded future researchers with the perspectives that the study of entrepreneurship and new ventures can be achieved in larger organizations as well as in SMEs.

The fact that this article has been consistently cited over time and that it has received more yearly references as time passes on shows it is still much in discussion now. As a foundational article in the field of entrepreneurship research, its evolution in a way reflects that of the field. The number of citations showed an increase in the 2000s while it effectively exploded in the 2010s. It displays how the field has truly come into its own and how interest has built over time to really emerge as an important research domain in the last few years.

As shown by the few examples presented in this chapter as well as with recommendations from Miller (2011), there are many future research opportunities originating from this article and the phenomena of EO and CE . An amazing feature of this article is that its main message has been mostly underexploited. As explained by Miller (2011), the purpose of the article was to discuss how distinct configurations in different contexts can result in divergent firm behaviors. The configurational perspective has not been overly discussed in the entrepreneurship literature (Wiklund and Shepherd 2005). It has the potential to become an important research stream in entrepreneurship.

Table 4.1 summarizes what Miller accomplished with his 1983 paper and his 2011 paper. It displays the importance of some of the elements introduced in those papers and how they are represented by the author through some quotes. EO, CE and the configurational approach would be the most important concepts put forward in Miller (1983). Meanwhile, a process perspective and alternative operationalizations of EO can be taken from Miller (2011). Finally, based on recommendations from Miller (2011), some work can be further done in order to improve the EO field.

The research in the early years has served to strengthen the concept of EO. It effectively provided a perspective of how firms can adopt an entrepreneurial posture. In recent years, EO has expended its research scope to different topics. Research has evolved into different streams. Each of them explores a different way of pushing the limits of knowledge on the working of EO. We are a long way from the original work of Miller (1983) but he initiated a stream of research that has developed into a major domain of entrepreneurship. It has still much to be developed and, furthermore, it has the potential to spread to even more streams of research.

References

Anderson, B. S., & Eshima, Y. (2013). The influence of firm age and intangible resources on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm growth among Japanese SMEs. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(3), 413–429.

Anderson, B. S., Kreiser, P. M., Kuratko, D. F., Hornsby, J. S., & Eshima, Y. (2015). Reconceptualizing entrepreneurial orientation. Strategic Management Journal, 36(10), 1579–1596.

Barringer, B. R., & Bluedorn, A. C. (1999). The relationship between corporate entrepreneurship and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 20(5), 421–444.

Boling, J. R., Pieper, T. M., & Covin, J. G. (2016). CEO tenure and entrepreneurial orientation within family and nonfamily firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(4), 891–913.

Brouthers, K. D., Nakos, G., & Dimitratos, P. (2015). SME entrepreneurial orientation, international performance, and the moderating role of strategic alliances. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(5), 1161–1187.

Burgelman, R. A. (1984). Designs for corporate entrepreneurship in established firms. California Management Review, 26(3), 154–166.

Covin, J. G., & Miles, M. P. (1999). Corporate entrepreneurship and the pursuit of competitive advantage. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 23(3), 47–47.

Covin, J. G., & Miller, D. (2014). International entrepreneurial orientation: Conceptual considerations, research themes, measurement issues, and future research directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(1), 11–44.

Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1989). Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strategic Management Journal, 10(1), 75–87.

Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1991). A conceptual model of entrepreneurship as firm behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(1), 7–25.

Covin, J. G., & Wales, W. J. (2012). The measurement of entrepreneurial orientation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(4), 677–702.

Eddleston, K. A., Kellermanns, F. W., Floyd, S. W., Crittenden, V. L., & Crittenden, W. F. (2013). Planning for growth: Life stage differences in family firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(5), 1177–1202.

Eggers, F., Kraus, S., Hughes, M., Laraway, S., & Snycerski, S. (2013). Implications of customer and entrepreneurial orientations for SME growth. Management Decision, 51(3), 524–546.

Eshima, Y., & Anderson, B. S. (2017). Firm growth, adaptive capability, and entrepreneurial orientation. Strategic Management Journal, 38(3), 770–779.

Kellermanns, F. W., Eddleston, K. A., Sarathy, R., & Murphy, F. (2012). Innovativeness in family firms: A family influence perspective. Small Business Economics, 38(1), 85–101.

Lechner, C., & Gudmundsson, S. V. (2014). Entrepreneurial orientation, firm strategy and small firm performance. International Small Business Journal, 32(1), 36–60.

Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 135–172.

McDougall, P. P., & Oviatt, B. M. (2000). International entrepreneurship: The intersection of two research paths. Academy of Management Journal, 43(5), 902–906.

McKinley, W., Latham, S., & Braun, M. (2014). Organizational decline and innovation: Turnarounds and downward spirals. Academy of Management Review, 39(1), 88–110.

Miller, D. (1983). The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Management Science, 29(7), 770–791.

Miller, D. (2011). Miller (1983) revisited: A reflection on EO research and some suggestions for the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(5), 873–894.

Mintzberg, H. (1973). Strategy-making in three modes. California Management Review, 16(2), 44–53.

Mintzberg, H. (1979). The structuring of organizations (Vol. 203). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Rauch, A., Wiklund, J., Lumpkin, G. T., & Frese, M. (2009). Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 761–787.

Wiklund, J., & Shepherd, D. (2005). Entrepreneurial orientation and small business performance: A configurational approach. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(1), 71–91.

Zahra, S. A., & Covin, J. G. (1995). Contextual influences on the corporate entrepreneurship-performance relationship: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 10(1), 43–58.

Zellweger, T., & Sieger, P. (2012). Entrepreneurial orientation in long-lived family firms. Small Business Economics, 38(1), 67–84.

Zellweger, T. M., Nason, R. S., & Nordqvist, M. (2012). From longevity of firms to transgenerational entrepreneurship of families introducing family entrepreneurial orientation. Family Business Review, 25(2), 136–155.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Dao, B.A.K. (2018). Danny Miller (1983) and the Emergence of the Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO) Construct. In: Javadian, G., Gupta, V., Dutta, D., Guo, G., Osorio, A., Ozkazanc-Pan, B. (eds) Foundational Research in Entrepreneurship Studies. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73528-3_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73528-3_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-73527-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-73528-3

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)