Abstract

Even though it has been theorized that initiatives on sustainable development should pursue an equilibrium among social, environmental and economic dimensions, several studies have pointed that an unbalance exists regarding the consideration of the three dimensions. However, there is little evidence to support such unbalance. Thus, in this article, we propose a tool to determinate sustainable dimensions balance by representing sustainable efforts according to their orientation. To test our tool, we reviewed about ten years of literature from top tier journals dealing with Sustainable Supply Chain issues to establish the sustainable efforts undertaken. Our results visually unveil unbalance on research in this field and show that most research is oriented to environmental and economic aspects, leaving social issues aside.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The introduction of sustainable development (SD) inside an organization is transversal because its adoption affects almost all business areas. In this connection, the logistics and supply chain activities are primarily concerned not only for traditional association with environmental pollution but also because of their potential to propose solutions in terms of sustainability [1,2,3]. Thus, this interaction between SD and logistics activities originated a new application area named sustainable logistics or, in a more complex and larger view, sustainable supply chain (SSC).

The scientific community has nearly followed the growth of the newcomer discipline. However, as an emerging research area, the study of SSC has not yet a consensus framework and even the implications of this notion are neither stable nor clear [4, 5]. From a theoretical perspective, a SSC “performs well on both traditional measures of profit and loss as well as on an expanded conceptualization of performance that includes social and natural dimensions” [6]. This definition, which is inspired by the principles of Elkington’s triple bottom line [7], establishes a new perspective of the traditional economic-only view of performance in supply chains and puts in evidence the needs of balance between the three dimensions of SD – i.e. environmental, social and economic. Nonetheless, several academics have pointed that an unbalance exists regarding the consideration of the three dimensions [4, 5, 8]. Even when this unbalance has been suggested, no evidence has been offered to support this claim. Thus, in this article, we propose a tool for representing sustainable efforts according to their orientation. The aim of this tool is to determinate if there are sustainable dimensions that are more privileged than others. To test the tool, we reviewed about ten years of literature from top tier journals in the fields of Supply Chain Management and Operations to establish the sustainable efforts undertaken.

In this article, first, we present the different trends used in literature to study the integration of SD issues in logistics and supply chain activities. Then, we present a description of the developed tool for representing sustainable efforts in the three dimensions of SD. The results of the evaluation of the tool are presented in Sect. 4, and discussed in Sect. 5. Finally, conclusions are presented.

2 From a Partial to a “Truly” Sustainable Supply Chain Perspective

As mentioned earlier, there is not consensus about the integration of SD in the domain of supply chain management. This integration has been discussed in the literature through three trends, which differ from one another by focusing on different dimensions of SD (Fig. 1). The main considerations of these approaches are detailed below.

2.1 Green Supply Chain Management

Most extended efforts to introduce the sustainability issues in supply chain management considerations have been oriented “to green the supply chain”. In this regard, environmental management and supply chain management were coupled together to originate the notion of Green Supply Chain ManagementFootnote 1 (GSCM) [3] as a confirmation that a global view of the supply chain is more adequate to address environmental factors than local optimizations [9]. An important aspect of GSCM thinking is that activities that are oriented to reduce the ecological impact are, at the same time, intended to become a source of economic profit [10, 11]. In this context, environmental and economic dimensions of sustainability are directly concerned.

2.2 Logistics Social Responsibility

The GSCM approach is centered in environmental and economic issues but fails to consider the social dimension of SD. In this regard, some research has been conducted to propose a more complete approach that also considers social. Those works fall in the group of what is known as Logistics Social Responsibility (LSR)Footnote 2.

As their name signals, LSR approaches are based on the precepts of Corporate Social Responsibility. Thus, LSR focuses in five dimensions: environment, safety, human rights, diversity and philanthropy [12]. Nonetheless, until the last few years, the dominant tendency was to study those aspects as standalone [13]. The above definitions represent an effort to position social and environmental issues at the center of the debate. In addition, even when Murphy and Poist [14] explicitly include economic importance, authors seem to forget this dimension in their empirical investigation [4]. Nowadays, however, research works that deal with LSR concerns are not numerous.

2.3 Sustainable Supply Chain Management

As we presented, research on LSR does not include explicitly economic aspects. This omission could suppose a no desirable situation as some authors considers that any social or environmental initiative cannot be everlasting without economic success [15, 16]. This consideration resulted on the notion of Sustainable Supply Chain Management (SSCM), which refers to “the management of material, information and capital flows as well as cooperation among companies along the supply chain while taking goals from all three dimensions of SD into account which are derived from customer and stakeholder requirements” [2].

Carter and Rogers [4] proposed a framework for SSCM based on Elkington’s Tripple-Botton Line [7]. In this framework, all social and environmental activities that can harm or not help the economic dimension must be placed outside of the zone where the economic dimension overlaps the other two. The “best” area, the intersection of three dimensions, is the “truly sustainable” area, where activities balance performance in environmental, social and economic aspects. It is presumed that organizations seeking success in integrating SD on their supply chain activities should pace their efforts on initiatives falling inside the intersection of the three dimensions of SD.

3 Proposing a Tool to Represent Sustainable Efforts by Their SD Orientation

3.1 Representation Principle

We developed a tool to represent visually the efforts undertaken to integrate SD according to the dimension to which each effort belongs (social, economic or environmental), but also if they belong to any intersection of two or all three dimensions. To develop our tool, we took the Elkington’s sustainability representation [7] as a basis (Fig. 2).

The triple bottom line for representing SD [7]

We propose to represent quantitatively the initiatives on sustainability as a circle area or an intersection circle area. This circle areas represent values corresponding to financial investments or any kind of countable items – e.g. articles, protects, words. Accordingly, initiatives on SD must be classified previously based on their orientation. For instance, if some initiatives involve only environmental issues, these initiatives must be classified as “only environmental”. Otherwise, if the initiatives involve two or three SD dimensions (e.g. environmental and social), these initiatives must be classified as “environmental and social”.

3.2 Tool Implementation

In this research, we followed a design science approach [19]. The fundamental principle of design science research is that both knowledge and understanding of a design problem, as well as the solution of the problem itself, are acquired through the construction of an artifact [20]. In our case, the resulting artifact corresponds to a tool for representing sustainable efforts according to their orientation. The implemented tool considers three circles, each one of them representing the Economic, Social and Environmental dimensions, with an area proportional to the number of components identified for each category. The implementation is based on a Monte Carlo approach to calculate the area of a surface, which can be a whole circle or the shared area between two or more circles.

As depicted in the Fig. 3, the process starts with a random generation of points which can be used to determine surface areas and to change the position of the circles on the screen. In the next step, we determine the appropriate distance between the Economic and Social circles, based on their number of components and therefore their total and shared areas. Then, we start a series of iterations where we assign a random position to the Environmental circle and we calculate the error as the difference between the shared areas between the three circles and the expected value for those areas. The next step in the process consists in determining the position for the Environmental circle, based on the lowest error achieved in the previous set of iterations. Finally, we draw the three circles on the screen with a different set of color for each one of them and their shared areas.

4 Evaluating the SSC Research Orientation

The purpose of this evaluation is to use the tool to identify if there are sustainable dimensions that are more privileged than others by reviewing about ten years (2002–2012) of literature from top tier journals in the fields of Supply Chain Management and Operations. These fields were chosen because they have been traditionally associated with the research in supply chain management, logistics, and transport. we reviewed from top tier journals dealing with Sustainable Supply Chain. We truncated the period of our review due to contractual embargo periods on our databases subscriptions.

To identify the top-tier journals in the selected fields, we conducted a review in several journal rankings, retaining the journals that were ranked at one the two higher level on at least one ranking. Since our research was confined to articles published before 2012, we consulted the standing rankings at that time. Thus, the rankings used for this evaluation are listed below:

-

The journal ranking of the Center for Advanced Studies in Management and Economics (CEFAGE) from the University of Évora. 2nd Edition 2009–2011.

-

The journal ranking of the National Centre for Scientific Research. Classification of journals in economics and management 2011.

-

The Erasmus Research Institute of Management (ERIM) journal list 2011–2015 from the Erasmus University of Rotterdam.

-

The Association of Business Schools (ABS) Academic Journal Quality Guide version 4 published in 2010.

-

The ranking of journals VHB-JOURQUAL 2.1 published in 2011 by the German Academic Association for Business Research.

-

The Australian Business Deans Council Journal Ratings List 2010.

-

The Excellence in Research for Australia (ERA) 2010 Ranked Journal List from the Australian Research Council and the 2011 adjusted ERA Rankings List from the University of Queensland Business School (UQBS).

-

The 2011 review of journal rankings for transport, logistics and supply chain management from the Institute of Transport and Logistics of the University of Sidney.

-

The 2011 ranking of scientific management journals of the National Foundation for Companies Management Academic Education (FNEGE).

For testing the pertinence and validity of our journal selection approach, we reviewed the quartile indicator of each journal on the SCImago (and SCOPUS) Journal Rank (SJR). We validated the journals that were classed on the quartiles Q1 and Q2 in 2012. Accordingly, we retained six Production and Operations journals and seven Supply Chain and Logistics journalsFootnote 3:

Production and Operations Journals

-

International Journal of Operations and Production Management

-

International Journal of Production Economics

-

International Journal of Production Research

-

Journal of Operations Management

-

Production and Operations Management

-

Production Planning and Control

Supply Chain and Logistics Journals

-

International Journal of Logistics Management

-

International Journal of Logistics: Research and Applications

-

International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management

-

Journal of Business Logistics

-

Journal of Supply Chain Management

-

Supply Chain Management: An International Journal

-

Transportation Research Part E

Then, we collected the articles of these journals for our review. We systematically applied the following filters on the databases where the selected journal was present. We conducted these queries in the title, keywords and abstract fields:

-

Sustainable AND supply chain

-

Sustainable AND logistics

-

Green AND supply chain

-

Green AND logistics

-

Sustainability AND supply chain

-

Sustainability AND logistics

-

Social AND sustainable AND supply chain

-

Social AND sustainable AND logistics

-

Social AND sustainability AND supply chain

-

Social AND sustainability AND logistics

-

Social AND responsibility AND supply chain

-

Social AND responsibility AND logistics

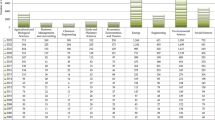

Using these research parameters, we retained 193 articlesFootnote 4. To analyze the orientation of each article in terms of the three dimensions of sustainability – i.e. environmental, social and economic. Each article was carefully read and coded according to the main orientation of their problematic. For coding, we use the coding scheme presented in Appendix. Since some articles deal with quite a few problems at the same time, an article could be coded in one or more dimensions. The results of the coding are presented in Table 1.

To represent unbalance graphically, we used the results from coding as inputs to the tool we developed. With a total of 1,000,000 points to calculate the area of each circle, and 100,000 random positions for the Environmental circle, the minimum error achieved was 1.9118, and the resulting graphical representation is depicted in the figure on the right side of the Fig. 4.

Figure 4 shows graphically this imbalance between the three dimensions of sustainability in supply management research. In the left side of the figure, the traditional representation of SD is presented. In this representation, “truly” sustainability is reached in the intersection area of three dimensions. In the right part of the figure, the representation obtained, in this research, visually let us evidence the dimensional reduction presumption in SSC research. First, most of research is oriented to the intersection of environmental and economic aspects. Second, social issues are the less studied from the three aspects. Finally, even when the sustainability area – the intersection of three dimensions – looks interestingly important, less than half of articles in this area (8 of 20) is empirical in nature, the others are theoretical contributions.

5 Discussion and Conclusions

In this article, we proposed a tool for representing sustainable efforts according to their orientation. The aim was to determinate if there are sustainable dimensions that are more privileged than others. Our results suggest that academic research on SSC are mainly concerned with a GSC view (environmental and economic concerns) rather than with a “truly” SSC perspective, which also integrates social concerns. Even though theoretical contributions on the subject have called for balancing social, economic and environmental concerns [4, 6, 16], our results report that social is, by far, the dimension of SD that has received less attention in comparison to the other two.

Besides our results, originated from the academic world, some questions emerge about how SD issues are understood in practice by organizations: Is there a balance in practice? Is it important to pursuit a “truly” SSC? And what are the drivers and barriers for balancing SSC efforts? These questions should be at the origin of further research conducted within a private context. Since the tool can represent not only coding units, such articles or words, but monetary values, it can become a useful mechanism to represent and analyze investments in SD. These studies could also evaluate their robustness and utility of the tool in practice when organizations use it to evaluate their efforts on SD.

Even though our results are limited only to a small spectrum of SD concerns, those of logistics and transports, further research could be interested to expand these results on context others than SSC. Our study was also limited by access to databases. Another study can also be addressed to analyze the evolution of the research orientation in the last five years. Finally, further research could be interested to improve the algorithms used in this study. Another venue lies on the use of text mining techniques to analyze textual corpus without laborious and time consuming human intervention. In this sense, methods to find frequencies or topic analysis could become new input to feed the proposed tool in this research.

Notes

- 1.

Some authors, as Handfield et al. [17], use the term Environmental Supply Chain Management instead of GSCM. All the same, both terms are equivalents.

- 2.

- 3.

The full results can be provided by request.

- 4.

The full list can be provided by request.

References

Carter, C.R., Easton, P.L.: Sustainable supply chain management: evolution and future directions. Int. J. Phys. Distr. Log. 41(1), 46–62 (2011)

Seuring, S., Müller, M.: Core issues in sustainable supply chain management - a Delphi study. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 17(8), 455–466 (2008)

Srivastava, S.K.: Green supply-chain management: a state-of-the-art literature review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 9(1), 53–80 (2007)

Carter, C.R., Rogers, D.S.: A framework of sustainable supply chain management: moving toward new theory. Int. J. Phys. Distr. Log. 38(5), 360–387 (2008)

Pagell, M., Shevchenko, A.: Why research in sustainable supply chain management should have no future. J. Supply Chain Manag. 50(1), 44–55 (2014)

Pagell, M., Wu, Z.: Building a more complete theory of sustainable supply chain management using case studies of 10 exemplars. J. Supply Chain Manag. 45(2), 37–56 (2009)

Elkington, J.: Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business. New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island (1998)

Yawar, S.A., Seuring, S.: Management of social issues in supply chains: a literature review exploring social issues, actions and performance outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 141(3), 621–643 (2017)

Koh, S.C.L., Gunasekaran, A., Tseng, C.S.: Cross-tier ripple and indirect effects of directives WEEE and RoHS on greening a supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 140(1), 305–317 (2012)

Constantini, V., Crespi, F., Marin, G., Paglialung, E.: Eco-innovation, sustainable supply chains and environmental performance in European industries. J. Clean. Prod. 155(2), 141–154 (2017)

Rao, P., Holt, D.: Do green supply chains lead to competitiveness and economic performance? Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 25(9), 898–916 (2005)

Carter, C.R., Jennings, M.M.: Logistics social responsibility: an integrative framework. J. Bus. Logist. 23(1), 145–180 (2002)

Carter, C.R., Jennings, M.M.: Social responsibility and supply chain relationships. Transp. Res. E-Log. 38(1), 37–52 (2002)

Murphy, P.R., Poist, R.F.: Socially responsible logistics: an exploratory study. Transp. J. 41(4), 23–35 (2002)

Frota Neto, J.Q., Bloemhof-Ruwaard, J.M., Van Nunen, J.A.E.E., Van Heck, E.: Designing and evaluating sustainable logistics networks. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 111(2), 195–208 (2008)

Seuring, S., Müller, M.: From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 16(15), 1699–1710 (2008)

Handfield, R., Sroufe, R., Walton, S.: Integrating environmental management and supply chain strategies. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 14(1), 1–19 (2005)

Ciliberti, F., Pontrandolfo, P., Scozzi, B.: Logistics social responsibility: standard adoption and practices in Italian companies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 113, 88–106 (2008)

March, S.T., Smith, G.F.: Design and natural science research on information technology. Decis. Support Syst. 15, 251–266 (1995)

Hevner, A.R., March, S.T., Park, J., Ram, S.: Design science in information systems research. MIS Quart. 28(1), 75–105 (2004)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix: Coding Scheme

Appendix: Coding Scheme

See Table 2.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Loza-Aguirre, E., Morales, M.S., Roa, H.N., Armas, C.M. (2018). Unveiling Unbalance on Sustainable Supply Chain Research: Did We Forget Something?. In: Rocha, Á., Guarda, T. (eds) Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Technology & Systems (ICITS 2018). ICITS 2018. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol 721. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73450-7_26

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73450-7_26

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-73449-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-73450-7

eBook Packages: EngineeringEngineering (R0)