Abstract

In the Iranian film industry, movies have been traditionally distributed for many years through a physical market in the form of CDs or DVDs after they satisfied their theatrical exhibition. Virtual space however has provided rival companies with an opportunity to gain a share in the movie distribution market. A notable rival here is Saba Idea Company. As a small media entrepreneur, the company has launched a film distribution website, dubbed ‘Filimo’, in a bid to fetch a portion of the distribution market. Having enjoyed the assistance of two cell phone companies and a major ADSL service provider in Iran, Filimo has already presented a major rivalry to the physical movie distribution system. This paper follows Kranenburg and Ziggers’ innovation-centered business model to discuss a set of capabilities that might have helped the small media entrepreneur in I.R.Iran to develop a strategy that is promising for its competition in the film distribution market. In the meantime, I discuss the business environment of film distribution in Iran with a focus on challenges facing the traditional models of distribution following the emergence of the Internet.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Most opportunities in the field of media can be traced back to their roots in technological invention and/or innovation (Hang 2016: 20). But, it remains a major hurdle for media firms ‘to choose a particular organizational mode for the development of new business opportunities’ (Emami and Khajeheian Forthcoming: x). In Hang’s view, venture capital investment helps ‘incubate’ more opportunities and create or discover future opportunities with a view to ‘spread risks from the company’s existing product lines’ (2016: 20). The venturing process, on the other hand, would serve as a challenge to economic bases and sustainability of established media (ibid).

There are several organizational modes for engaging in such venturing investment; a new business creation may occur either within a hierarchical framework or through market modes. In the former, the new entities start and develop within an existing corporate body, either by establishing the new business inside or by acquiring another business to merge with the firm’s own operation. In the latter, venturing may be conducted by setting up new business entities outside the company’s boundary or making strategic alliances in a cooperative base (Venkataraman 1997: 131). The choice of mode may depend on several factors, including cost (transaction cost and agency costs), speed and market power (strategic behavior) and/or appropriability (resources and capabilities view of the firm) (ibid, 132).

Either way, the venturing process is led by technological advances that help attend to customers’ demands, and in order to maintain the capability for innovativeness, the key is to acquire information about changes in consumer patterns as well as technological changes and possibilities (Achtenhagen Forthcoming: x). These technologies are ‘disruptive’ (Funk 2005: 98) in that they improve some aspects of the product performance while sacrificing others, thus making the new technologies appropriate for a new set of customers. As Funk states (97), lead users of the old technology are largely the initial users of the new technology. Funk also notes that incumbents in the new technological market are often the winners since they can use their existing processes and business models to introduce products that are based on the new technology.

Internet has emerged as a major case of the new technological advances that lead the new media business. Feldmann and Zerdick argue that a central feature of the Internet is its nature as a network, ‘which fosters the emergence and development of positive externalities’ (2005: 19). They consider these positive externalities as ‘the rapid attainment of a critical mass as a first mover’ and ‘the opportunity it presents for expanding essential basic functions of communication’ (21).

In Feldmann and Zerdick’s argument, the film business serves as a major branch of the media industry that is subject to major changes on account of the Internet, with small, independent companies having the capacity of using the Internet for marketing and distribution purposes (25). And, as Kehoe and Mateer put it, the Internet has helped transform the conventional rules of film distribution (2015: 94). An example of the transformation may be seen in a shift from physical distribution of films to virtual distribution through the Internet as is the case in the Islamic Republic of Iran.

This transformation of distribution rules however has never been free from the challenges involved in a stiff competition between traditional distribution companies and the emerging ones on the Internet. Such challenges, among others, arise from how media companies organize the new business activities that seize the opportunities and how to develop ‘new competences’ through these opportunities and, ultimately, generate profits (Hang 2016: 20–21).

Taking the account of such challenges, some argue for an ‘adequate adaptation’ to the changing environment that involves a strategy meant to ‘to obtain, integrate and reconfigure resources and capabilities’ (Kranenburg and Ziggers 2013: 239). Media firms, under the strategy, are supposed to ‘simply build capacity to manage a customer responsive network’ (ibid). The strategy is treated as part of a business model called innovation-centered business model.

Kranenburg and Ziggers note that digital technology has eroded the benefits of scale to media companies. They approve Oh’s argument (1996) that the existing resources and capabilities available to traditional media companies are no longer sufficient to deal with the new demands and requirements in the changing market (ibid). They argue that media firms would no longer need to make the ‘three-pronged investment’ that involves manufacturing, marketing and management as Chandler once offered in 1990; instead, they may simply build capacity to manage a customer responsive network (ibid).

Kranenburg and Ziggers argue for the formation of capacity-building ‘network firms’ and note ‘flexible specialization and contracting may today yield greater advantages than economies of scale and scope generated internally’ (240). Accordingly, media firms have to rethink their traditional manner of revenue generation, the structure of their organization, their core competencies and the way of creating value through new opportunities; actually, they have to redesign their business model by which to create, deliver and capture value (ibid). This may, among others, be accomplished through new forms of collaboration.

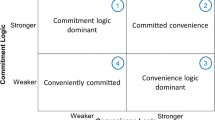

Media firms, as Kranenburg and Ziggers put it, must actively work to disrupt their own advantages as well as the advantages of their competitors by continuously challenging the existing capabilities. To that effect, they argue for a strategy of both exploiting the existing businesses and exploring new ones, calling it ‘a strategy of ambidexterity’ (ibid, 244).

According to the researchers, a set of ‘dynamic capabilities’ are required to become an ambidextrous organization, run an innovation-centered business model and obtain a sustainable competitive advantage (245). These dynamic capabilities are meant to help the company to create, adjust and keep relevant stock of capabilities.

Kranenburg and Ziggers define a ‘dynamic capability’ as a deeply embedded set of skills and knowledge exercised through a process, enabling a company to stay synchronized with market changes and to stay ahead of competitors. It entails the capabilities that enable organizational fitness and help shape the environment advantageously.

They consider two main functions for dynamic capabilities: (1) sensing environmental changes that could be threats or opportunities, by scanning, searching and exploring across markets and technologies (‘market sensing capabilities’); (2) responding to the changes by combining and transforming available resources through partnerships or acquisition (‘relational capabilities’). These dynamic capabilities would help the media companies to select the business model reconfiguration for delivering value and capturing revenues (ibid).

The present paper applies the innovation-centered business model and the concept of ‘dynamic capabilities’ to discuss and explain a set of capabilities that might have helped an online film distribution company in Iran to design an environmentally-advantageous business model for successfully competing with traditional, physical distributers. It studies the case of the newly-launched Iranian film distribution website ‘Filimo’ as well as a corporate venture (or collaboration) between several digital media companies that underpin its development and competition.

First, the business environment of film distribution in Iran is discussed with a focus on challenges facing the traditional models of distribution following the emergence of the Internet. In the meantime, the author discusses how a digital company reconfigured a business model based on the Internet and innovated a virtual solution for the distribution of films. A discussion of the business model of the digital company follows with a focus on the capabilities that might have helped it to advance the innovation. The data were gathered through a combination of observations and study of related website.

1 Building on Advantages of Digitalization

In the Iranian film market, movies are usually placed in a physical home distribution network after they satisfy their theatrical sales. Every week, average two domestic movies and five foreign ones hit the distribution chain, according to latest figures at hand (Rezvani and Marhamat 2012: 186). These movies are available at video clubs, supermarkets, and many retail shops nationwide.

The distribution business has growingly become promising as customers, especially those who have failed to cover the theatrical sales, show an increasing tendency for watching their favorite movies at home (ibid). At the same time, the value of patents for home-produced movies has grown strongly over the past few years and even outperformed those of the theatrical sales, further making the movie distribution business profitable (ibid). The situation has prompted media entrepreneurs and particularly movie producers to pay attention to the distribution network as a major source of profit to the extent that some producers primarily focus on the network as their target market.

Movies have been traditionally purchased by certain institutes in charge of the physical distribution network before being distributed nationwide in the form of CDs or DVDs. Figures released by the IRI Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance show that nearly 35 million copies of domestic or foreign movies are distributed through the network nationwide every year (ibid, 187). Movies are mass copied and distributed at 200–500 thousand copies and some are even mass copied at double the number. The mass-copying figures may logically stand for the extent of those customers who prefer to watch movies outside the theatrical sales cycle.

The emergence of the Internet proved a source of motivation for the Iranian entrepreneurs in film distribution business. They had for a while kept an eye on the profitable business and at the same time, were aware about the advantages of digitalization, including in film distribution. The Internet left its impact on the market with customers growingly showing an appeal for the advantages of virtual space. In the course of several years, the physical distribution network suffered a blow with one third of the copies never sold in 2012, only to be returned to warehouses (Rezvani and Marhamat 2012: 187).

Numerous large and small digital media companies started to operate over the Internet with an eye on the advantages of digitalization including Saba Idea Company. Founded in 2005, the small media company started work as a media industry entrepreneur in the virtual space with a stated goal of ‘value creation in the Internet-based business,’ according to its website at www.sabaidea.com. The company developed and launched several Iranian portals that absorbed high levels of hits. These included a free of charge video sharing website dubbed ‘Aparat’.

Billed as the Iranian version of Youtube, the video sharing service quickly grew popular among the Iranian customers and was even welcomed by the Farsi-speaking populations in the neighboring countries of Afghanistan and Tajikistan. It was appreciated as the top video sharing digital service in the Internet in the I.R.Iran with over four million hits a day, back in 2014.

Aparat as an Internet-based digital video sharing service enjoyed several advantages that actually mend for disadvantages of the physical distribution market. These are discussed below.

The Internet removed the need for the customers to go to shops or video clubs to buy their favorite movies in the form of CDs or DVDs. It also facilitated access to a wide range of movies at a single time while the physical market’s possibilities were much more limited.

Customers had to operate special devices to play the CDs or DVDs while they easily watch movies on the Internet through auto-run applications. Also, they may watch movies online in private on their smart phones while it is much of a group work to watch CDs or DVDs at home. They may also save their favorite movies in their smart phones and retrieve it whenever wished unlike the constraints facing the home devices. It is notable that the advantage was actually a co-advantage of personal data storing devices and the Internet.

One more co-advantage of the combination of Internet and storing devices was that the customers could decide to watch specific points of the movies they wish more conveniently and share them with larger groups of friends or colleagues. The co-advantage was especially interesting in that it helped satisfy the demand of customers to quickly retrieve a specific point of the films for relevant use in social communication.

Additionally, customers holding smart phones may enjoy the entire already discussed advantages anytime anywhere as they have got free from the constraint of plug and socket. This is also a co-advantage of the Internet and portable, tiny power storage devices.

Add to these the low cost and minimal wear and tear in film materials in the form of compressed files that are available through the Internet and stored in smart phones unlike the relatively higher costs of CDs and DVDs and extensive wear and tear in the hard material.

There are two more key advantages of film sharing through the Internet that are related to media economics. For one thing, the Internet thank to media convergence has enabled the customers to watch films while being able to pause to check their SMSs or do other media-related jobs unlike traditional film play devices. And, it has enabled the customers to share their movies with one another without losing access to their own material. As public goods (Reca 2006: 183), films on CDs or DVDs may be shared with others but holders would have no access to their material as long as they are used by others. Storage of films on smart phones or desktops through the Internet however enabled the customers to share them with others without losing access to their material.

Building on these technology-driven advantages, the Aparat video sharing service gained a growing share of the film distributing market over time. Customers were actually developing a habit for using the virtual space for watching their favorite movies at the expense of the physical distribution market. They were further motivated due to the fact that the Aparat content was free of charge, though advertisement accompanied its content.

The habitual evolution intensified amid an expansion of the Internet and mobile phone services nationwide. The Aparat video sharing service had helped the Saba Idea company to appropriate a growing portion of the critical mass of film watchers available in the physical distribution market.

As said earlier, the video sharing service was acclaimed as the top service of the kind on the Internet in I.R.Iran, having received over four million hits a day back in 2014. The media company appeared to have gained a critical mass to create a capacity for capturing value in the market. This led to the creation of the Filimo innovation in February 2015 by which to offer the customers a platform for watching Iranian and foreign movies online.

While having combined the digitalization-driven advantages of Aparat, the Filimo had its own advantages as well. For example, the digital distribution service was offered through an application compatible with the speed of the Internet in Iran. The service started to run in 2015 under the motto of ‘watch films without a break.’ The motto alluded to an intermittent break in the Internet services offered by some service providers in Iran. By the motto, Saba Idea Company actually promised its customers to provide them with an unbreakable service. The motto also alluded to the access of a small portion of Iranians to high speed internet. An official report says only four percent of Iranian users had access to high speed internet back in 2013 (Itna, URL). Much more Iranians at present have access to high speed internet however the internet services nationwide are largely low-speed and face intermittent break.

Adding to its own advantages, the digital service could be accessed via smart phones and smart TVs through a special application that allows the customers to adjust the quality and resolution of their favorite movies or download them.

Moreover, Saba Idea Company premiered the film distribution service with a debut series titled ‘Dandoun Tala’ (the golden toothed) that was directed by the acclaimed Iranian director Davoud Mirbagheri. Interestingly enough, the series were simultaneously distributed through the physical distribution market nearly at an equal cost.

Filimo was launched in 2015 but only came in vogue a few months ago when the Saba Idea Company received a joint venture by three large media companies, including two cellar phone companies (namely Hamrah-e Avval and Irancell) and an ADSL service company, called Asiatech. These companies hold internet services in Iran in large part. The appeal of the video sharing service among film watchers had served as a motivation for the companies to join the venture investment.

As of February 2017, the two mobile service providers offered free of charge traffic data to any customer who wished to receive video content from the Filimo website (Isna, URL). Subscribers to the mobile service providers may log on a digital shop titled ‘Filimo home cinema audio and video products’ and receive access to the entire available content at the shop with free of charge traffic. Irancell however demands its subscribers to pay 3000 rials (nearly 10 cents) a day for the service.

The free of charge traffic service is slated to run until September 2017 with likely extensions. It has already been extended once.

Irancell also sends its subscribers promotional items on the Filimo content. For example, when a client applies for charging his or her Simcard, Irancell sends him/her a notification message that ends up in a promotional content, encouraging the subscriber to use the Filimo content free of charge.

For its part, Asiatech, as the largest internet service provider in Iran, has offered a range of discounts to its subscribers for the use of the Filimo content. The Filimo portal at www.filimo.com opens with an ad that promotes Asiatech’s discounts for those subscribers that visit the film distribution website. Asiatech only charges its subscribers 10,000 rials (nearly 30 cents) a month for the service.

Asiatech’s portal too has a series of promotional items on the Filimo content. When a subscriber enters the website at www.asiatech.ir to check his or her status or apply for related services, s/he would be treated with a large-size looping gif that promotes the Filimo content. Also, subscribers to Asiatech may find a VoD icon at the bottom of the portal that is linked to a separate page on video-on-demand services. Six VoD services are promoted there, including the Filimo content.

2 A Business Model Focused on a Platform Shift

As said earlier, movies in the physical distribution market in Iran have been mass copied and distributed at 200–500 thousand copies and some are even mass copied at double the number. The author also took the figures as a logical parameter for estimating the extent of those customers who prefer to watch movies outside the theatrical sales cycle.

The author would like to argue that a critical mass for creating a new market was already available at the physical distribution market in Iran before the Internet services were focused on as a source of market capabilities. It follows that the Internet only helped to move this critical mass to another market sector by convincing the customers to choose for the virtual platform for watching their favorite films. Therefore, besides the situations where the Internet helps the rapid attainment of a critical mass, as Feldmann and Zerdick argue (2005: 21), we might consider cases where the Internet helps the appropriation of this critical mass by moving it from one market sector to another; actually, the critical mass already exists before it is appropriated (rather than attained) by a competitor. In the case of the present paper, Aparat was actually gradually appropriating a critical mass that was already attained by the physical distribution market.

It follows that Aparat innovation helped the holder company to appropriate (or attain, anyway) the critical mass because it was a ‘first mover’ in the digital movie sharing market, to use Feldmann and Zerdick’s concept (2005: 21).

Also, Aparat was actually used as a capacity ‘to disrupt the advantages’ (Kranenburg and Ziggers 2013: 244) of competitors in the physical distribution market. This capacity, as discussed above, was created thank to new advantages offered by the Internet for film distribution. This disrupting initiative took a boost from the fact that the Aparat content was free of charge, though advertisements accompanied the content on the company’s portal as a strategy of attention economy (see Napoli 2001).

Furthermore, having been an ‘incumbent’ (Funk 2005: 98) in the video sharing services online, Saba Idea Company enjoyed the capability to start to create and capture value in the digital film distribution market on the Internet.

Also, as a small media company, it achieved the capacity to create value in the digital distribution market through forming a capacity-building ‘network firm’ (Kranenburg and Ziggers 2013: 240) that involved three large media companies as well.

These large media companies joined a venture investment with Saba Idea based on the mode of ‘making strategic alliances in a cooperative base’ (Venkataraman 1997: 132). Under the venture investment, the small media company made for an inadequacy in its organizational capabilities while the large companies advanced the innovation in the digital film distribution market in a bid to disrupt the physical market and create a profitable business on the Internet.

Taking the account of the Aaparat service launch, Saba Idea Company appears to be among the first media firms to sense the environmental changes that followed the emergence of the Internet (‘market sensing capabilities’) and was, apparently, the first to respond to the changes by combining and transforming its available resources through partnerships with several large media companies (‘relational capabilities’) before the Filimo launch.

The Company’s available resources included ‘digital application compatibility’ and ‘easy access via smart devices’ that were combined with the capabilities of ‘reach to massive customers’ and ‘promotional discounts’ of the large media companies under collaboration. These dynamic capabilities helped the small media company to select a business model reconfiguration for delivering value and capturing revenues. The Company responded to the environmental change by developing an innovation and joining collaboration in a bid to create a capacity in response to the customers’ demands amid the emergence of digitalization.

With a critical mass already at hand in the physical distribution market, the Company might only have to run an innovation-centered business model that would help it appropriate the critical mass. So, it apparently run a business model that focused on a strategy of motivating the customers in the physical distribution market to shift to a new, digital platform on Internet for watching their favorite movies. Filimo innovation was intended to do the job. Movie customers however needed first to change their attitude concerning the physical distribution market. This mission of attitudinal change was carried out through the Aparat video sharing service several years before the Filimo was launched.

The Company capitalized on the advantages of digitalization in its bid to change the attitude of the customers towards watching films online. Aparat’s free of charge services were also instrumental in having the customers to change their attitude towards digital film services on the Internet. And, it only took a few years to accomplish the mission; as said earlier, in the course of several years, the physical distribution network suffered a blow with one third of the copies never sold in 2012, only to be returned to warehouses (Rezvani and Marhamat 2012: 187).

But, to have the customers to pay for watching movies online through Filimo, the Company has had to obtain more capabilities. For one thing, it has to attain access to and encourage a massive range of potential customers who might be willing to pay for online watching. The access and encouragement were provided by the large media companies which offered the digital services at major discounts to their massive clientele. Furthermore, it has had to facilitate the film watching possibilities to the customers and the mission was to be accomplished through a digital application that was compatible with the technical features of the Internet nationwide and its easy accessibility on smart devices.

Content-wise, the Company premiered Filimo with a debut series (Dandoun Tala) that was directed by a famous Iranian director in an apparent bid to further motivate the customers to pay for watching films online. In doing so, the Company sought to apply ‘brand leverage strategy’ (Reca 2006: 194) in the competition for film distribution. The simultaneous distribution of the series through the physical distribution market would have provided the Company’s managers and other market experts, including those with the large media companies that started collaboration with the Company, to weigh the levels of motivation among customers for watching films online.

Whether or not the Filimo innovation may win the rivalry against the physical distribution market remains to be seen, however, a promising Filimo innovation would absolutely serve as a strong source of motivation for the large media companies to start a new business on their own accord in terms of a ‘strategic acquisition’ (Eliasson and Eliasson 2005).

The large media companies enjoy resource and operational competitive advantage while the small entrepreneurial company enjoys ‘the strength of its innovation and new idea’ (Khajeheian 2013: 128) in the digital film distribution market. The large media companies may concentrate on the Filimo idea and consider a strategic acquisition once it proves to be a lucrative deal.

Of note is that the large media companies have actually filled a gap of ‘financial and technical facilitators’ that are supposed to ‘invest or lend for commercialization of new innovations,’ ‘evaluate and filter best innovations offered by media entrepreneurs,’ and ‘introduce them to larger media companies’ for purchase, acquisition or joint venture (ibid, 129).

The large media companies seem to have been launching a temporary, low-risk joint venture with the Filimo holder company in a bid to appraise its potential competitive advantage; I’d like to call the process a hitchhiking effect as they are giving the holder company a free lift intended to gain an appraisal about its potential competitive strength.

3 Conclusion

To conclude, the author would like to discuss the probable future trends ahead of the small, entrepreneurial company behind the Filimo innovation.

In terms of dynamic capabilities, the company’s available resources, including ‘digital application compatibility’ and ‘easy access via smart devices’ combined with ‘reach to massive customers’ (attained through larger media companies) may easily be threatened by new entrants in the digital distribution market. Actually, these resources and capabilities seem not to be ‘intensive’ (Khajeheian 2013: 134) enough to help it stay the course and endure the competition.

On the other hand, new entrants may help the company to advance the strategic goal of platform shift in the distribution market as part of a ‘collaboration to increase selling power’ (see Johnson et al. 2005: 262). Accordingly, the company may join its dynamic capabilities with those of new entrants in a collaborative venture aimed at advancing a shift of platform from the physical distribution market to the digital one.

In terms of strategic options, the competency-orientation theory (Eliasson 1996, 1998) appears relevant for it discusses the situations where small firms are supposed either to grow aggressively on their own or being acquired strategically. Accordingly, the small media company may either sell the innovation and start a new one, or cede entirely and work as part of larger media companies, or ‘aggressively continue to act as an independent firm which aims to grow’(Khajeheian 2013: 128). Nevertheless, should the company decide to stay the competition as an independent firm, it would logically face a heavy challenge arising from new entrants in the Iranian digital market as mentioned earlier. These new entrants are expected to arrive in at high numbers due to the existing low levels of barriers in terms of costs, regulations and market opportunities.

A growing number of entrants, on the other hand, would lead to an aggregation of entrepreneurial companies in the digital space, followed by an accumulation of digital innovations. Though risky for the Filimo holder company, the likely situation would prove instrumental for the development of ‘exit markets’ as an essential part of a viable media market. Exit markets serve as a bed for strategic acquisitions, offering a supply of radically new innovations embodied in ‘small new firms’, with these innovations having been moved beyond the entrepreneurial stage by venture maker, which in turn supply the exit market with strategic investment opportunities (Eliasson and Eliasson 2005: 102). Exit markets prove essential for an efficient media market and their absence may force media entrepreneurs to carry the process of commercialization of an innovation from A to Z, which is practically inefficient and results in heavy pressure (Khajeheian 2013: 130).

An aggregation of entrepreneurial companies in the digital distribution market, as discussed, may also provide a ground for the emergence of technical and financial facilitators, as a major determinant of the media market’s efficiency. These facilitators may ‘evaluate and filter best innovations offered by media entrepreneurs and introduce them to larger media companies’ (ibid, 129). Facilitators serve as a key element in the development of entrepreneurship as they ‘bridge between the innovation advantage of small companies and operational advantages of large companies’ (Khajeheian and Tadayoni 2016: 128).

The very emergence of the Filimo as a digital platform for film distribution offers evidence of an emerging exuberant media market in Iran full of potentials for media entrepreneurs. Further researches might offer more insights into the dynamics of the market as a developing media market.

References

Achtenhagen, L. (Forthcoming). Entrepreneurial orientation—an overlooked theoretical concept for studying media firms. Global Media Journal—Canadian Edition, 10(1), xx–xx.

Eliasson, G. (1996). The firm, its objectives, its controls and its organization. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Eliasson, G. (1998). The nature of economic change and management in the knowledge-based information economy. KTH, TRITA IEO-R, 1998, 19.

Eliasson, G., & Eliasson, A. (2005). The theory of the firm and the markets for strategic acquisitions. In Cantner et al. (Eds.), Entrepreneurships, the New Economy and Public Policy (pp. 91–115). Berlin: Springer.

Emami, A., & Khajeheian, D. (Forthcoming). Revisiting effectuation through design view: A conceptual model of value creation in media venturing. Global Media Journal—Canadian Edition, 10(1), xx–xx.

Feldmann, V., & Zerdick, A. (2005). E-merging media: The future of communication. In E-merging media: Communication and the media economy of the future (pp. 15–29). Berlin: Springer.

Funk, J. (2005). New technologies, new customers and the disruptive nature of the mobile Internet: Evidence from the Japanese Market. In E-merging media: Communication and the media economy of the future (pp. 97–115). Berlin, Germany: Springer.

Hang, M. (2016). Media corporate entrepreneurship: Theories and cases. Berlin, Germany: Springer.

Isna. (2017). Irancell subscribers allowed download films for free at Filimo. Available at http://www.isna.ir/news/95110906004. Accessed in July 19, 2017

Itna. (2013). Only 4 percent of Iranians have access to high-speed Internet. Available at http://itna.ir/fa/doc/news/27979. Accessed in July 19, 2017

Johnson, G., et al. (2005). Exploring corporate strategy. Essex: Pearson Education Limited.

Kehoe, K., & Mateer, J. (2015). The impact of digital technology on the distribution value chain model of independent feature films in the UK. The International Journal on Media Management, 17, 93–108.

Khajeheian, D. (2013). New venture creation in social media platform; Towards a framework for media entrepreneurship. In Handbook of social media management: Value chain and business models in changing media markets (pp. 125–142). London: Springer.

Khajeheian, D., & Tadayoni, R. (2016). User innovation in public service broadcasts: Creating public value by media entrepreneurship. International Journal of Technology Transfer and Commercialization, 14(2), 117–131.

Napoli, P. (2001). The audience product and the new media environment: Implications for the economics of media industries. Journal of Media Management, 3(2), 66–73.

Reca, A. A. (2006). Issues in media product management. In Handbook of media management and economics (pp. 181–201).

Rezvani, M., & Marhamat, L. F. (2012). Improvement of distribution system in home show network using XTRIZ approach. Entrepreneurship Development, 5(3), 185–203.

van Kranenburg, H., & Ziggers, G. W. (2013). How media companies should create value: Innovation generated business models and dynamic capabilities. In M. Friedrichsen & W. Muhl-Benninghaus (Eds.), Handbook of social media management. London: Springer.

Venkataraman, S. (1997). The distinctive domain of entrepreneurship research. In J. Katz & R. Brockhaus (Eds.), Advances in entrepreneurship, firm emergence and growth (Vol. 3, pp. 119–138). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hajmohammadi, A. (2018). Competitive Capabilities in Film Distribution Market: The Case of Filimo. In: Khajeheian, D., Friedrichsen, M., Mödinger, W. (eds) Competitiveness in Emerging Markets. Contributions to Management Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71722-7_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71722-7_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-71721-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-71722-7

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)