Abstract

This chapter situates the concept of ESP within the Spanish university context, which is characterised by diversity. This means that ESP instructors must re-adapt the absolute and variable characteristics of ESP to the Spanish teaching and learning environment. A possible way to do this is to instruct learners in the use of free online dictionaries, which are information tools that are accessible through the Internet with or without paying a fee. These tools are especially adequate for gaining knowledge, such as the concepts and conceptual framework scaffolding a domain. Within this framework, this chapter illustrates a way to use using free online dictionaries for gaining knowledge. This consists of two stages: first, the use of a template that includes 10 characteristics for deciding on the adequacy of the dictionaries to be used and, second, the recommendation of two specific types of dictionaries for gaining knowledge. The implementation of both stages allowed me to propose the use of collaborative dictionaries, such as Wikipedia and/or specialised dictionaries, to assist ESP learners to gain knowledge of specific domains.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Diversity

- Adaptation

- Free online dictionaries

- Adequacy

- Two specific types of dictionaries

- Collaborative dictionaries

- Wikipedia

- Specialised dictionaries

- Business

- Economics

1 Introduction

Since its inception in the mid-1960s, the concept of English for specific purposes (ESP) has referred to the teaching and/or learning of the English language in ways that meet specified learners’ needs. Dudley-Evans and St. John (1998) enumerate the characteristics of ESP that are accepted in the majority of the ESP community:

- I.

Absolute Characteristics

ESP is defined to meet specific needs of the learner;

ESP makes use of the underlying methodology and activities of the discipline it serves;

ESP is centred on the language (grammar, lexis, register), skills, discourse and genres appropriate to these activities.

- II.

Variable Characteristics

ESP may be related to or designed for specific disciplines;

ESP may use, in specific teaching situations, a different methodology from that of general English;

ESP is likely to be designed for adult learners, either at a tertiary level institution or in a professional work situation. It could, however, be for learners at secondary school level;

ESP is generally designed for intermediate or advanced students;

Most ESP courses assume some basic knowledge of the language system, but it can be used with beginners. (pp. 4–5)

Within the above-mentioned general framework, researchers are currently concerned with several issues, three of which are relevant for this chapter: (a) the discursive construction of genres, for instance, Hafner’s (2013) description of a problematic situation involving the process of the transition novice professional writers experience when they move from school to professional practice; (b) the influence of cultural components, e.g., Zhang’s (2013) analysis of a study on the different reaction posed by international business practitioners receiving business letters and (c) the use of multimedia for teaching and learning specialised vocabularies, for example, Rusanganwa’s (2013) investigation of the integration of information and communication technologies in undergraduate physics students’ teaching of English technical vocabulary.

This chapter follows along these same lines and will focus on the use of online dictionaries for assisting ESP learners to upgrade their knowledge of a particular ESP domain, in this case, business and economics. This objective needs some clarification. The first is that the concept of dictionary is used to refer to any reference work that has been designed for punctual consultation. This means that dictionary is used in this chapter as an umbrella term that refers to glossaries, dictionaries, terminological knowledge bases, term banks, lexica etc. The second clarification is concerned with the concept of knowledge, which is different from skills. Knowledge refers to the concepts underlying a particular domain. Upgrading a learner’s knowledge is necessary for working with ESP texts, e.g., the technical texts used in different ESP courses.

ESP courses are usually one of three groups or types (Carver 1983, pp. 132–133): (a) English as a restricted language, for instance, the language of air traffic controllers; (b) English for academic and occupational purposes, broken down into two sub-types: English for academic purposes (EAP) and English for occupational purposes (EOP), respectively, for example, English for business and economics and (c) English with specific topics, e.g., English for attending conferences and symposia. To the best of my knowledge, only Type b courses are part of the normal teaching curriculum of colleges and universities: English with specific topics and English as a restricted language are situational language courses, in other words, types of vocational courses that are only offered once specific needs are identified. Gatehouse (2001) partly concurs with this view:

This type of ESP [Type c] is uniquely concerned with anticipated future English needs of, for example, scientists requiring English for postgraduate reading studies, attending conferences or working in foreign institutions. However, I argue that this is not a separate type of ESP. Rather it is an integral component of ESP courses or programs which focus on situational language. This situational language has been determined based on the interpretation of results from needs analysis of authentic language used in target workplace settings. (Heading: Types of ESP: Last paragraph)

Vocational courses are different from regular courses in many ways. For the purpose of this chapter, I will only mention that learners enrolled in these courses need different types of reference works. For instance, learners enrolled in Type a courses typically need dictionary data for recipients. This means that a reference work such as the Glossary for Pilots and Air Traffic Services Personnel (Transport Canada 2009) is excellent, as it contains only the data needed in the situations where it will be used, which are the only possible situations in which pilots are placed when the air controller contacts them (Fig. 1):

Dictionary entry in the Glossary for Pilots and Air Traffic Services Personnel (Transport Canada 2009)

Example 1 shows a brief definition of the term and its French equivalent (because of Canada’s language policy), as the pilot and the air traffic controller only need a clear and easy-to-understand description of the situation communicated, i.e., an exact meaning of the term describing the situation: They must limit the possibility of misunderstanding to a minimum. This is what they have in the above glossary, and therefore the glossary is excellent for performing the recipient function (Fuertes-Olivera and Tarp 2014; Tarp 2008, 2010a) (Fig. 1).

In English for academic and occupational courses, the use situation is different and more complex, as it is also concerned with producing, translating and upgrading (or acquiring) knowledge. This chapter will explain the teaching and learning situation in Spanish universities (Sect. 2) and then discuss two different theoretical frameworks for approaching the use of reference works in such situations (Sect. 3). Section 4 will apply one of the approaches discussed above to some free online dictionaries that could be used in the framework described in Sect. 2. A final conclusion summarises the main points discussed and offers ideas for future research.

2 EAP and EOP Teaching and Learning in Spanish Universities

English for academic and occupation purposes refers to the English language needed for immediate use in a study environment, i.e., English for academic purposes (EAP), or for use later in a job, i.e., English for occupational purposes (EOP). This distinction is based on the means used for achieving an end and not on the end itself (Gatehouse 2001). In other words, both sub-types are so closely related that it is easy to find ESP courses that contain skills that are needed in both EAP and EOP environments, e.g., reference skills are needed when a student is still in the university, e.g., for submitting assignments, and in many job environments, e.g., when preparing market research for launching a new product. I think that this is the situation that typically occurs in Spanish universities; therefore, I will not differentiate between the two sub-types in the following.

Recent research, (e.g., Fuertes-Olivera and Arribas-Baño 2008), has refined the category of semi-expert initially described in Bergenholtz and Kaufmann (1997), and has defended the concept of three subtypes of semi-experts in the teaching and learning environment associated with ESP courses taught and learnt in Spanish universities: (a) semi-experts from other related fields, (b) students from unrelated disciplines, and (c) translators and interpreters. For instance, business English courses in Spanish universities are usually open to students from different majors; therefore, some students have a broader knowledge of business and economics discourse than others. To sum up, the main characteristic of potential ESP learners in Spanish universities is that they are heterogeneous, which puts into doubt the adequacy of one absolute characteristic, i.e., that ESP aims to meet specific needs of learners, and two variable characteristics, i.e., that ESP is designed for specific disciplines and is used in specific teaching situations. In other words, the adjective specific merits a reinterpretation within the teaching/learning environment of Spanish universities.

In my view, the word specific in the ESP teaching/learning environments at Spanish universities has two implications. The first is that we need to re-evaluate the role that some internal and external factors play. This means a deep analysis of the following questions is needed:

-

1.

What is the role of instructors (i.e., teachers) inside and outside the classroom? For instance, is team-teaching (i.e., a course taught by an expert in the subject field and English teacher) possible and economically viable?

-

2.

Must instructors have a working knowledge of the domain they are teaching? Or how can instructors have a working knowledge of the different domains their students belong to?

-

3.

How should a needs analysis be carried out and which needs must be addressed primarily? Or do instructors perform the same needs analysis for students belonging to different domains?

-

4.

Which teaching materials must be used? Must they always be authentic material? If so, authentic for whom?

The second implication relates to some recent findings on basic characteristics of Spanish learners and on the nature of specialised vocabulary. Fuertes-Olivera and Gómez Martínez (2004) have found that thinking in L1 and reading are correlated. This means that the more students read in English, the less they think in Spanish. They have also found that although factors such as attendance and homework are judged positively by students, they tend to pay them little or no attention at all. These results are consistent with the Spanish university framework, where students do not regularly attend lectures and/or tutorials, and English instructors have to struggle with inappropriate conceptions of L2 within Spanish society. Finally, they have also found that the principles and practices associated with communicative methods are sometimes absent from Spanish teaching tradition. For example, in some nurseries children are taught written words and numbers (for instance, irregular verbs) instead of spoken functional expressions and formulae. These findings indicate that ESP instructors have to devote some time to be sure that their students correctly understand and accept the daily routines of communicative methodologies, which assumes that ESP learners have no special lexicographical training nor have been explained which dictionary type is more adequate for solving their specific needs. Among these daily routines of communicative methodologies, the use of pedagogically oriented online dictionaries is highlighted in this chapter.

Fuertes-Olivera and Piqué-Noguera (2013) and Fuertes-Olivera and Tarp (2014) have also found that around 70% of the word stock currently used in specialised domains, such as accounting, consists of multi-word terms, i.e., terms composed of three or more orthographic words. Table 1 shows English terms that include the word method, distributed by number of orthographic words.

To the best of my knowledge, the above finding has not merited much attention so far. Recent works on teaching specialised vocabulary, e.g., corpus studies such as Gavioli (2005) and Gajšt (2013), have focused on terms composed of one or two orthographic words. In other words, they have left out of their analysis around 70% of the word stock of many domains. What makes these multi-word terms really interesting is that they are coined for restricting meaning, i.e., both their language profile and conceptual meaning is specific and has to be learnt on an individual basis (Fuertes-Olivera and Tarp 2014).

Taken together, the above-mentioned two implications indicate that the word specific may have an idiosyncratic interpretation, i.e., a meaning that is acceptable within the Spanish university context. Within this context, I believe that specific must refer to courses prepared for teaching learners that have a stated and precise purpose, which is, firstly, to learn to communicate in English, and, secondly, to learn to differentiate the nuances of meaning that are associated with restricted situations, i.e., the specific meaning of multi-word terms. In practical terms, this means that the design of ESP curricula in Spanish universities must cater to general needs, i.e., needs that all possible ESP learners have, typically social English; partially special needs, i.e., needs that may be partially restricted, typically to learn to read faster or to learn the jargon of the trade; and all-purpose specific needs, i.e., needs that all learners will have sooner or later, e.g., to learn to deliver a talk. This means that I am proposing a syllabus that may need more teaching hours than the one usually accorded to ESP courses in Spanish universities (most courses have 6 ECTS (European credit transfer system)).

A possible solution to overcome time constraints is to understand (and apply) the impact of multimedia on learning. Mackey and Ho (2010, p. 387), for instance, cite research by Baruque and Melo (2004), Deubel (2003) and Mayer (2001) on the influence of behaviourist, constructionist and cognitive approaches that aim to understand the impact of multimedia on learning. Behaviourism explains that learning is a change in behaviour due to experience and the function of building associations between the stimulus event and the response event. Constructivism argues that learning ‘is constructed by the complex interaction among students’ existing knowledge, the social context, and the problem to be solved’. (Baruque and Melo 2004, p. 346) Finally, cognitivism asserts that learners gain a deeper level of understanding through the associations made between words and images in an integrated environment (Mayer 2001).

Below, I will defend the use of free online dictionaries in the Spanish environment described so far. In particular, I will focus on ways for using free online dictionaries with the aim of meeting one all-purpose specific need, which is that all learners enrolled in a specific ESP course must have a sound understanding of the facts, i.e., concepts, of a particular domain. This could be achieved assuming the following: (i) Reference works are tools, i.e., they are prepared to satisfy potential needs in potential use situations, as claimed by proponents of the function theory of lexicography (Sect. 3, below) and (ii) the Internet must be handled with care, as we must avoid the many dangers associated with the uncritical use of the Internet, e.g., the so-called Google effect, which is the suffocation effects users receive when they retrieve much more data than needed (Sect. 4).

3 Dictionaries as Tools

Fuertes-Olivera (2012) and Fuertes-Olivera and Tarp (2014) describe two basic orientations in the Kingdom of Lexicography. One of them is illustrated with postulates that basically stem from the eighteenth century, e.g., Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (1755). These postulates claim that making dictionaries is a craft or art (Landau 2001) without theoretical support (Atkins and Rundell 2008). This craft or art must be based on a proper understanding of the linguistic characteristics of language, i.e., lexicographers have to design and produce dictionaries under the tenets of linguistics, e.g., corpus linguistics (Sinclair 1991), or cognitive linguistics, e.g., frame-based semantics (Fillmore and Atkins 1992). Within this orientation, dictionaries are only concerned with describing the vocabulary stock of a language, using the tenets of linguistics for this endeavour. Within the realm of ESP, this orientation is very popular, for example, in the Cambridge Business English Dictionary:

The Cambridge Business English Dictionary is a brand new dictionary of over 35,000 business-related words, phrases and meanings used in business and the world of work.

Including the most up-to-date vocabulary from the rapidly evolving world of business and business English, the Cambridge Business English Dictionary is ideal for anyone studying business-related subjects and for anyone using English for their work.

The dictionary gives thousands of examples from real business texts, helpfully presented information about grammar, and there is a strong emphasis on collocation.

Informed by the unique Cambridge Business Corpus, the dictionary includes the very latest business-specific vocabulary.

Most of the words in the dictionary have a business subject label, such as Marketing, Finance, or Computing…. (Homepage. See at http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionaries/business-english/)

The second approach is furnished by the tenets of the function theory of lexicography, which is the academic construction originally initiated in the Centre for Lexicography at the University of Aarhus (Bergenholtz and Tarp 2002, 2003, 2004; Tarp 2008), which has since been subjected to continuous evolution. Fuertes-Olivera and Tarp (2014), for example, explain that lexicography is a millenarian cultural practice (almost 4000 years old) and an independent academic discipline with its own system of scientific theories. Being independent does not mean that it has been placed in a walled room away from the rest of the scientific disciplines into which human knowledge has been parcelled; instead, lexicography has relations with many other disciplines, e.g., specialised lexicography has relations with information science, linguistics, terminology and specific subject fields (Fuertes-Olivera 2018). This idea translates into the construction of dictionaries as tools and dictionaries that target specific needs in potential use situations. Regarding ESP, these needs arise in communicative situations, such as needs related to translating, reading or writing English texts, and/or cognitive situations, such as needs related to understanding concepts or the language characteristics of the subject field in question (see Fuertes-Olivera and Tarp 2014; for a discussion, see also Tarp 2010b, 2012).

The second approach defends the construction of dictionaries that are different from the above-mentioned Cambridge Business English Dictionary. For instance, we have constructed dictionaries that have dynamic dictionary articles with dynamic data, in other words, dictionaries that adjust the data displayed in the dictionary homepage to the requested usage situation. A case in point is the Diccionario Inglés-Español de Contabilidad, which displays data adjusted to four prototypical use situations. For instance, a Spanish translator of English accounting texts can search in the Diccionario Inglés-Español de Contabilidad: Traducción (Fuertes-Olivera et al. 2012c) or the Diccionario Inglés-Español de Contabilidad: Traducción de Frases y Expresiones (Fuertes-Olivera et al. 2012a). The first dictionary offers a Spanish and English definition of the English lemma, a Spanish equivalent with number and gender inflections, and several English collocations and examples that have been translated into Spanish. The same user can search in the second dictionary and retrieve all the phrases, i.e., collocations and examples (see Fuertes-Olivera et al. 2012b for a discussion of the concept of collocation in lexicography) in the dictionary article in which they are found, each described with definitions, examples, contextual clues etc. In other words, the first dictionary is typically used by novice translators whereas the second is much used by experienced translators.

To sum up, ESP learners have two main types of information tools at their disposal. One type follows a linguistics approach to dictionary making and is mostly concerned with dictionaries that target all-purpose specific needs rather than specific needs. The second type follows a lexicographic approach, which results in dictionaries that take into consideration the three key elements of any information tool: user needs, data types adjusted to meet user needs and access routes. In other words, this second approach is based on the main tenets of the function theory of lexicography, which posits that the core of lexicography is the design of utility tools that can be quickly and easily consulted with a view to meeting punctual information needs occurring for specific types of users in specific types of extra-lexicographic situations.

Most existing free online dictionaries are examples of linguistics-based dictionaries (Fuertes-Olivera 2012). Because they have not been designed and compiled for meeting specific needs, their users must perform a process of conversion in order to use them with confidence. Below I offer a template for making existing free online dictionaries adequate pedagogical tools in cognitive situations, such as for gaining business knowledge.

4 Free Online Dictionaries for Gaining Business Knowledge

Pedagogical dictionaries refer to dictionaries conceived in order to assist native and foreign language learning as well as knowledge learning (Fuertes-Olivera 2010; Fuertes-Olivera and Arribas-Baño 2008; Tarp 2005, 2008). Research on their use in a teaching/learning environment has produced surprising results. Al-Ajmi (2008), for example, has found that

the provision of examples along with definitions negatively affects students’ ability to understand unfamiliar English words. This finding clearly contradicts the common belief that examples are useful in both comprehension and production. It should, nevertheless, lead dictionary makers to think seriously about solutions to problems of constructing examples and definitions. (p. 22)

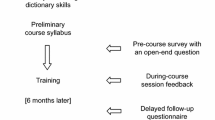

Al-Ajmi’s findings need confirmation, something that has not been achieved so far. A possible explanation for Al-Ajmi’s findings is that learners are not very skilful in using dictionaries. Lew and Galas (2008), for instance, have claimed that in spite of the various calls for including training in dictionary use in school and academic curricula, no large-scale teaching of dictionary skills has ensued, and current research into the effectiveness of training in dictionary use is lacking in convincing results. In my view, this training must have two stages.

The first stage is to explain to learners a theoretical model for analysing dictionaries. For instance, the functional approach to dictionary reviewing proposed by Fuertes-Olivera and Tarp (2014, pp. 130–134) can be an adequate initial step for evaluating dictionaries for ESP learners. This approach is a template of ten criteria, which are summarised below:

-

1.

Author’s view: Does the dictionary include outer texts that inform on relevant lexicographic characteristics, e.g., the targeted user(s), and expected use situations that the dictionary aims to cover? Similarly, have the compilers of the dictionary discussed the main characteristics of the dictionary in the lexicographic literature? With these questions, we emphasise how important the authors’ opinion is for building a theory of lexicography and its translation into real and working dictionaries.

-

2.

Function(s): Does an independent analysis of the dictionary match the information given in outer texts and lexicographic literature on the function(s) the dictionary aims to cover? In other words, do the data presented in the dictionary support the function(s) identified? The focus is on whether the data match the needs of the target group(s).

-

3.

Access routes: Does the dictionary contain access routes that favour the process of consultation? Focus is on whether the data are presented so that users can process them to get the information they need to solve their problems in a simple and easy way.

-

4.

Internet technologies: Is the dictionary using existing Internet technologies? If the answer is yes, is it using them adequately? The focus is on whether the dictionary offers options that favour consultation, for instance, dynamic articles with dynamic data.

-

5.

Lexicography: Does the dictionary make use of lexicographical theories and methodologies or is it based on other type of theories, e.g., cognitive linguistics as mentioned above?

-

6.

Production costs: Are lexicographers using time and money in a sensible way? For instance, why do some dictionaries, for example, many EU-funded projects, use so much funding when its results can be achieved with less funding?

-

7.

Information costs: Are lexicographers paying attention to the amount of time and effort users may need to look up, understand and interpret their findings? For instance, why do some dictionaries force users to search two or more times to retrieve data? In other words, are lexicographers paying attention to the distinction between comprehension- and search-related information costs discussed in the literature (Nielsen 2008)?

-

8.

Updating: Is the dictionary being updated regularly, which is a must in specialised lexicography?

-

9.

Experts: Are real experts in the field included in the production team of the dictionary? This is necessary in specialised lexicography to increase the quality of the data included, as we believe that other methods of extracting specialised knowledge, e.g., non-experts working with corpus data, cannot be used for compiling most dictionary articles.

-

10.

Data selection: Does the dictionary use reliable sources for selecting and treating the lexicographic data included in the dictionary article? This criterion aims to assess the reliabilism of both the raw material included and its lexicographical treatment. The focus is on considering whether or not the data included and its lexicographic treatment are the result of a process that is documented and knowledge based, i.e., that the data have been validated by experts. To sum up, investigating the reliability of the data selected and its lexicographic treatment is necessary and can be accomplished by, say, performing several random analyses of the data included and treated in the dictionaries reviewed.

This template will inform users about several needed issues. For instance, free online dictionaries such as the Glossary of Mortgage and Home Equity Terms (2012) are not recommended. They are basically promotional tools designed by organisations and/or companies—private or public, national or supranational etc.—with the aim of explaining the meaning of the terms they are using to refer to the basic characteristics of these organisations’ products and/or services. In other words, the genuine purpose of this Glossary is the description of the mortgage contracts of the company designing such a tool (Fig. 2).

In terms of the above functional framework, this dictionary does not describe its characteristics nor does it take into consideration lexicographical theories. It stands out because it signals a trend in today’s world, in which technology is no longer self-explanatory. Instead, technology

needs instructions, leaflets for describing the product, the installation procedures etc. In sum, modern terminology needs improving communication strategies. Communication between developer and user can only work if the text author and the text recipient share the same terminology, i.e., if a given term denotes exactly the same concept for author and reader. Language, and primarily written language, is the prerequisite for our modern technology. (Teubert 2005, p. 98)

The second stage is to explain to learners the specific characteristics of the free online dictionaries selected in the initial stage. In other words, this stage is mostly concerned with giving information about which dictionary articles they need in order to gain business knowledge such as facts and concepts that explain the conceptual characteristics of a domain. For instance, in the above-mentioned Spanish framework, gaining business knowledge is crucial, as many ESP courses are taught to students with different knowledge backgrounds. Having some knowledge of the subject field is necessary, for example, to write an ESP text.

At this stage, learners need dictionaries that provide information about key concepts and facts. There are three basic types of online dictionaries that users can consult to gain knowledge: (a) dictionary portals, (b) collaborative dictionaries and (c) well-conceived cognitive-oriented dictionaries.

Encyclopedia.com is a dictionary portal, i.e., ‘a data structure that is presented as a page or set of interlinked pages on a computer screen and provides access to a set of electronic dictionaries, and where these dictionaries can also be consulted as standalone products’ (Engelberg and Müller-Spitzer 2013, p. 1023). These authors also differentiate between several types of dictionary portals, with Encyclopedia.com being an example of a ‘dictionary search engine’, i.e., a system that provides outer and external access to dictionaries that do not exhibit interdictionary cross-referencing and whose search results are not presented uniformily. This system is not recommended, as it does not target learners; instead, it aggregates data and hence forces learners to disambiguate by themselves, which is problematic and difficult to achieve, as learners are not prepared to decide for themselves at this stage. In other words, dictionary search engines suffocate learners and will hamper their learning process. For instance, I searched the word motivation and retrieved several dictionary articles in several reference works, most of which contain around 6000 words, which is much more than ESP learners need and can easily understand.

Wikipedia is an example of a collaborative dictionary or collective free multiple-language Internet dictionary (Fuertes-Olivera 2009). Dictionaries such as Wikipedia can be used with confidence. Since the launch of Wikipedia in 2001, researchers have conducted several well-known comparisons of different encyclopaedias, typically Britannica and Wikipedia, with the stated goals of analyzing their degree of accuracy and deciding whether Wikipedia is a reliable source of information. This type of research starts by assuming that the Britannica should be regarded the most scholarly of the encyclopaedias, and therefore as a kind of yardstick against which new encyclopaedias have to be compared.

Research into Wikipedia as a reliable source of information offers mixed results. On the one hand, its editorial and authorship processes have been criticized. Santana and Wood (2009), for example, claim that in both systems there is a lack of transparency, and they argue that this ‘jeopardizes the validity of the information being produced by Wikipedia’ (p. 133). Criticism of Wikipedia has also reached the academic world. Gorman (2007) claims that Wikipedia is an ‘unethical resource unworthy of our respect’ (p. 274), and Lim and Kwon (2010, p. 213) indicate that some universities no not allow their students to cite Wikipedia in their assignments.

On the other hand, the few studies that have been conducted on the accuracy of Wikipedia paint a different story. For example, in 2005 the science journal Nature conducted a wide-ranging comparison of Wikipedia and Britannica’s level of accuracy in dealing with 50 scientific topics, concluding that the overall error ratio was 4:3 in Britannica’s favour; this less than overwhelming margin gained notoriety when Nature rejected the rebuttal sent by Britannica, describing Nature’s study as flawed and misleading. In a similar veil, Fuertes-Olivera (2013) has offered convincing results on his analysis of these two information tools. Fuertes-Olivera focused on the amount of conceptual data included in both reference works and found that they contained similar data, although organised in a different way, with Wikipedia using Internet technologies more consistently. For instance, the article for the word motivation contains a well-conceived table of contents and several hyperlinks that allow users to click on the required data, thus making Wikipedia adequate for gaining knowledge quickly and easily.

The Dictionary of Business and Management (Law 2012) is an example of a well-conceived specialised dictionary. This dictionary targets students and business professionals and offers them long and well-crafted definitions of business and management concepts. The definition of the word motivation (Fig. 3) is well suited for ESP learners, as this is what they really need when they are enrolled in an ESP course:

The entry for the word motivation in the Dictionary of Business and Management (Law 2012)

In terms of the above functional framework, the Dictionary of Business and Management seems to be based on lexicographical practices, makes use of experts, is updated, and assists any user who is in a cognitive situation and wishes to gain some quick knowledge about business and management. The data matches and supports the function identified and is adequate for the intended users and for the intended purpose of offering quick information about a specific subject field.

To sum up, this section has offered some clues on the use of online dictionaries for gaining business knowledge. I have been aiming to show what Gasparetti et al. (2009) have explained: that the principal advantages of web-based systems are to be seen in the opportunity to overcome restrictions such as a dearth of teaching resources, organise complex and tailored courses for single learners and evaluate their acquired knowledge levels more or less easily. Within the framework of Spanish universities, web-based systems such as free online dictionaries are adequate tools and merit use in the teaching and learning environment associated with ESP in Spain.

5 Conclusion

The concept of ESP, which was initially described in the 1960s, is being adapted to the conditions of the twenty-first century, especially with the coming of age of the Internet. This chapter has commented on some general characteristics of ESP courses in Spanish universities, which are characterised by the fact that Spanish ESP learners are very heterogeneous. This runs against the true nature of the concept of ESP, which has assumed that all ESP learners have similar language and conceptual levels. In other words, within the context of Spanish universities, ESP learners may be very different in two key aspects of ESP. The first is that the students enrolled in a particular ESP course may have very different conceptual backgrounds, e.g., we can have students from medicine and chemistry enrolled in a business English course. The second aspect is that students with very different English levels and teaching traditions can be enrolled in the same ESP course.

A possible way of dealing with the above teaching and learning environment is to focus on the pedagogical characteristics of specialised dictionaries, e.g., the dictionaries that can be used by Spanish students of business English. Following this idea, this chapter has posited that the Internet can offer ESP instructors and learners means for overcoming the difficulties posed by having learners with different conceptual backgrounds and English levels. Hence, this chapter has shown that we need some system for evaluating whether web-based systems can be adapted and used in a teaching and learning environment that is characterized by rapid changes and lack of focus.

Within this framework, this chapter has shown that the function theory of lexicography offers the theoretical foundation and practical application to evaluate the adequacy of free online dictionaries in meeting some of the needs observed in Spanish ESP learners. In particular, this chapter has presented a method involving two stages for ESP learners to overcome the difficulties they may have in acquiring (or upgrading) knowledge of the ESP they are studying: The first stage is the description of a template that contains ten features that can be used for guiding instructors and learners when they may need to upgrade their dictionary culture. The second stage enumerates a list of three types of dictionaries that could be used for gaining knowledge. The chapter elaborates how both collaborative and well-conceived free online dictionaries can be used for this task and that ESP learners must only spend their money acquiring well-conceived dictionaries, e.g., dictionaries that are updated regularly and result from the joint work of lexicographers, experts in the field and information science specialists.

References

Al-Ajmi, H. (2008). The effectiveness of dictionary examples in decoding: The case of Kuwaiti learners of English. Lexikos, 18, 15–26.

Atkins, B. T. S., & Rundell, M. (2008). The Oxford guide to practical lexicography. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baruque, L. B., & Melo, R. N. (2004). Learning theory and instructional design using learning objects. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 13(4), 343–370.

Bergenholtz, H., & Kaufmann, U. (1997). Terminography and lexicography. A critical survey of dictionaries from a single specialised field. Hermes, Journal of Linguistics, 18, 91–125.

Bergenholtz, H., & Tarp, S. (2002). Die moderne lexikographische Funktionslehre. Diskussionsbeitrag zu neuen und alten Paradigmen, die Wörterbücher als Gebrauchsgegenstände verstehen. Lexicographica, 18, 253–263.

Berngenholtz, H., & Tarp, S. (2003). Two opposing theories: On H.E. Wiegand’s recent discovery of lexicographic functions. Hermes. Journal of Linguistics, 31, 171–196.

Bergenholtz, H., & Tarp, S. (2004). The concept of dictionary usage. Nordic Journal of English Studies, 3, 23–36.

Cambridge Business English dictionary. http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/business-english/. Accessed 20 Jan 2017.

Carver, D. (1983). Some propositions about ESP. The ESP Journal, 2, 131–137.

Deubel, P. (2003). An investigation of behaviorist and cognitive approaches to instructional design. Journal of Education Multimedia and Hypermedia, 12(1), 63–90.

Dudley-Evans, T., & St. John, M. J. (1998). Developments in ESP: A multi-disciplinary approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Encyclopedia.com. http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/motivation.aspx. Accessed 20 Jan 2017.

Engelberg, S., & Müller-Spitzer, C. (2013). Dictionary portals. In R. H. Gows, H. Ulrich, W. Schweickard, & H. E. Wiegand (Eds.), Dictionaries. An international encyclopedia of lexicography. Supplementary volume: Recent developments with special focus on computational lexicography (pp. 1023–1035). Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Fillmore, C. J., & Atkins, B. T. S. (1992). Towards a frame-based organization of the lexicon: The semantics of RISK and its neighbours. In A. Lehrer & E. F. Kittay (Eds.), Frames, fields, and contrast: New essays in semantics and lexical organization (pp. 75–102). Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale.

Fuertes-Olivera, P. A. (2009). The function theory of lexicography and electronic dictionaries: Wiktionary as a prototype of collective multiple-language Internet dictionary. In H. Bergenholtz, S. Nielsen, & S. Tarp (Eds.), Lexicography at a crossroads: Dictionaries and encyclopedias today, lexicographical tools tomorrow (pp. 99–134). Bern: Peter Lang.

Fuertes-Olivera, P. A. (Ed.). (2010). Specialised dictionaries for learners. Berlin/New York: De Gruyter.

Fuertes-Olivera, P. A. (2012). On the usability of free Internet dictionaries for teaching and learning Business English. In S. Grander & M. Paquot (Eds.), Electronic lexicography (pp. 392–417). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fuertes-Olivera, P. A. (2013). Electronic encyclopedias. In R. H. Gows, H. Ulrich, W. Schweickard, & H. E. Wiegand (Eds.), Dictionaries. An International encyclopedia of lexicography. Supplementary volume: Recent developments with special focus on computational lexicography (pp. 57–68). Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Fuertes-Olivera, P. A. (Ed.). (2018). The Routledge handbook of lexicography. London: Routledge.

Fuertes-Olivera, P. A., & Arribas-Baño, A. (2008). Pedagogical specialised lexicography. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Fuertes-Olivera, P. A., & Martínez, S. G. (2004). Empirical assessment of some learning factors affecting Spanish students of business English. English for Specific Purposes, 23, 163–180.

Fuertes-Olivera, P. A., & Piqué-Noguera, C. (2013). The literal translation hypothesis in ESP teaching/learning environment. Scripta Manent, 8(1), 15–30.

Fuertes-Olivera, P. A., & Tarp, S. (2014). Theory and practice of specialised online dictionaries. Lexicography versus terminography. Berlin/New York: De Gruyter.

Fuertes-Olivera, P. A., Bergenholtz, H., Nielsen, S., & Amo, M. N. (2012a). Classification in lexicography: The concept of collocation in the Accounting Dictionaries. Lexicographica, 28, 291–305.

Fuertes-Olivera, P. A., Bergenholtz, H., Nielsen, S., Gómez, P. G., Mourier, L., Amo, M. N., Rodicio, Á. d. l. R., Ruano, Á. S., Tarp, S., & Sacristán, M. V. (2012b). Diccionario inglés-español de contabilidad: Traducción. In Base de Datos y Diseño: Richard Almind and Jesper Skovgård Nielsen. Hamburg: Lemma.com.

Fuertes-Olivera, P. A., Bergenholtz, H., Nielsen, S., Gómez, P. G., Mourier, L., Amo, M. N., Rodicio, Á. d. l. R., Ruano, Á. S., Tarp, S., & Sacristán, M. V. (2012c). Diccionario inglés-español de contabilidad: Traducción de frases y expresiones. In Base de Datos y Diseño: Richard Almind and Jesper Skovgård Nielsen. Hamburg: Lemma.com.

Gajšt, N. (2013). Technical terminology in standard terms and conditions of sale: A corpus-based study of high frequency nouns and their collocations. Scripta Manent, 7(2), 33–50.

Gasparetti, F., Micarelli, A., & Sciarrone, F. (2009). A web-based training system for business letter writing. Knowledge-Based Systems, 22, 287–291.

Gatehouse, Kristen. (2001). Key issues in English for specific purposes (ESP) curriculum development. The Internet TESL Journa,l 10. http://iteslj.org/Articles/Gatehouse-ESP. Accessed 20 Jan 2017.

Gavioli, L. (2005). Exploring corpora for ESP learning. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Glossary of Mortgage and Home Equity Terms. (2012). Retrieved on May 27, from https://www.wellsfargo.com/mortgage/tools/glossary/a

Gorman, G. E. (2007). A tale of information ethics and encyclopedias: Or is Wikipedia just another internet scam? Online Information Review, 31(3), 273–276.

Hafner, C. A. (2013). The discursive construction of professional expertise: Appeals to authority in barrister’s opinion. English for Specific Purposes, 32(3), 131–143.

Johnson, S. (1755). Dictionary of the English language. London: J. and P. Knapton.

Landau, S. (2001). Dictionaries: The art and craft of lexicography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Law, J. (2012). Dictionary of business and management (5th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lew, R., & Galas, K. (2008). Can dictionary skills be taught? The effectiveness of lexicographic training for primary school-level Polish learners of English. In E. Bernal & J. DeCesaris (Eds.), Proceedings of the XIII Euralex congress (pp. 1273–1385). Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

Lim, S., & Kwon, N. (2010). Gender differences in information behaviour concerning Wikipedia, an unorthodox information source? Library and Information Science Research, 32, 212–220.

Mackey, T. P., & Ho, J. (2010). Exploring the relationships between web usability and students’ perceived learning in web-based multimedia (WBMM) tutorials. Computers and Education, 50, 386–409.

Mayer, R. E. (2001). Multimedia learning. Santa Barbara: Cambridge University Press.

Nielsen, S. (2008). The effect of lexicographical information costs on dictionary making and use. Lexikos, 18, 170–189.

Rusanganwa, J. (2013). Multimedia as a means to enhance teaching technical vocabulary to physics undergraduates in Rwanda. English for Specific Purposes, 32(1), 36–44.

Santana, A., & Wood, D. J. (2009). Transparency and social responsibility for Wikipedia. Ethics for Technology, 11, 133–144.

Sinclair, J. (1991). Corpus, concordance, collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tarp, S. (2005). The pedagogical dimension of the well-conceived specialised dictionary. Ibérica, 10, 7–21.

Tarp, S. (2008). Lexicography in the borderland between knowledge and non-knowledge. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Tarp, S. (2010a). Functions of specialised learners’ dictionaries. In P. A. Fuertes-Olivera (Ed.), Specialised dictionaries for learners (pp. 39–53). Berlin/New York: De Gruyter.

Tarp, S. (2010b). Reflections on the academic status of lexicography. Lexikos, 20, 450–465.

Tarp, S. (2012). Do we need a (new) theory of lexicography? Lexikos, 22, 345–356.

Teubert, W. (2005). Language as an economic factor: The importance of terminology. In G. Barnbrook, P. Danielsson, & M. Mahlberg (Eds.), Meaningful texts. The extraction of semantic information from monolingual and multilingual corpora (pp. 96–106). London/New York: Continuum.

Transport Canada. (2009). Glossary for pilots and air traffic services personnel. Ottawa: Ministry of Transport. http://www.tc.gc.ca/publications/EN/TP1158/PDF%5CHR/TP1158E.pdf. Accessed 20 Jan 2017.

Zhang, Z. (2013). Business English students learning to write for international business: What do international business practitioners have to say about their texts? English for Specific Purposes, 32(3), 144–156.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, the Junta de Castilla y León for financial support (Grants FF12011-22885 and FFI2014-52462-P and VA 067A12-1, respectively) and also to Dr. Lidia Taillefer for inviting me to write this chapter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Fuertes-Olivera, P.A. (2018). ESP and Free Online Dictionaries. In: Muñoz-Luna, R., Taillefer, L. (eds) Integrating Information and Communication Technologies in English for Specific Purposes. English Language Education, vol 10. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68926-5_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68926-5_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-68925-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-68926-5

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)