Abstract

There has been a major shift in research on second language motivation in the last fifteen years, with researchers becoming more and more interested in how this attribute changes over time rather than merely establishing the reasons for learning and seeking relationships between levels of motivation and attainment (cf. Dörnyei, 2005; Dörnyei & Ryan, 2015; Ushioda & Dörnyei, 2005; Dörnyei & Ryan, 2012). As a result, there are more and more studies which seek to determine how learners’ motives and the intensity of their engagement change over longer periods of time but also such which are aimed to track fluctuations in motivation in the course of tasks, lessons or sequences of such lessons, also attempting to pinpoint contextual and individual factors responsible for such changes. The chapter reports the results of a study, which constitutes part of a larger-scale empirical investigation using retrodictive qualitative modeling (RQM) (Dörnyei, 2014a) and falls within the former category by tracing the motivational trajectories of two English majors. This is done with a view to gaining insights into the dynamic nature of their motivation, identifying the factors that affected their motivational processes at different educational levels, seeking explanations of their successes and failures, and trying to identify distinctive profiles of these students. The results show that RQM is indeed capable of providing insights into motivational dynamics, although the procedure also suffers from some limitations.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- L2 motivation

- Motivational dynamics

- Retrodictive qualitative modeling

- L2 motivational self system

- Ideal L2 self

1 Introduction

The last two decades or so have witnessed a major shift in research on second language (L2) motivation from studies approaching it as a relatively stable attribute of learners to empirical investigations of its dynamic nature, both in relation to the reasons for undertaking the challenge of learning a second or foreign language and the intensity of the motivated learning behavior (e.g., Dörnyei, 2005, 2014b; Dörnyei & Ryan, 2015; Dörnyei & Ushioda, 2011; Dörnyei, MacIntyre, & Henry, 2015). One manifestation of this shift is the process-oriented period in the study of L2 motivation, initiated, by theoretical models proposed, among others, by Williams and Burden (1997), and Dörnyei and Ottó (1998), which, while differing with respect to specific stages, make a clear-cut distinction between the emergence of motivation (i.e., choices, decisions or goals) and engagement in the process of learning as such (i.e., feelings, behaviors, reactions). This approach has been taken even further in studies representing the socio-dynamic period in the study of L2 motivation which, in the words of Ushioda and Dörnyei (2012, p. 398), is “(…) characterized by a focus on the situated complexity of the L2 motivation process and its organic development in interaction with a multiplicity of internal, social, and contextual factors (…) [and] a concern to theorize L2 motivation in ways that take account of the broader complexities of language learning and language use in the modern globalized world”. Such a view of motivation in second or foreign language learning is reflective of two theoretical stances that have dominated research on this individual difference variable in recent years. One of them is complex dynamic systems (CDS) theory (e.g., Larsen-Freeman, 2015; Larsen-Freeman & Cameron, 2008), which allows viewing L2 motivation as a prime example of such a system, based on the assumption that it involves “(…) motivational conglomerates of motivational, cognitive, and emotional variables that form coherent patterns or amalgams that act as wholes” (Dörnyei, 2014b, p. 520). The other is the theory L2 motivation self system (Dörnyei, 2005, 2009, 2014c), comprising three components, that is ideal L2 self (i.e., representing aspirations concerning mastery of a given L2), ought-to self (i.e., reflective of expectations of others and the desire to ward off adverse consequences), and L2 learning experience (i.e., amalgams of internal and external influences on engagement in L2 learning), all of which are in a constant state of flux (Henry, 2015). This said, it has to be emphasized that research on motivational dynamics need not or perhaps even should not be grounded in a single theoretical position (cf. Pawlak, 2015), but, rather, it should involve different methodological approaches and employ a variety of data collection tools to allow as multifaceted and differentiated insights into this phenomenon as possible. The chapter contributes to this current line of inquiry by reporting on a study which, employing the research template known as retrodictive qualitative modeling (RQM), investigated the motivational trajectories of two Polish university students majoring in English.

2 Overview of Previous Research on Motivational Dynamics

Research on the temporal dimension of motivation can have as its aim exploring changes in this respect over longer periods of time, such as months, years or even decades, but it can also aspire to trace fluctuations in L2 motivation on much shorter timescales, such as days, minutes or even seconds, as the case might be with sequences of foreign language classes, single classes or the performance of specific language tasks. When it comes to the former line of inquiry, relevant studies are representative of the process-oriented period and they can be undertaken to provide insights into the changes in both the motives underlying the decision to initiate or persist in the process of language learning, or issues tied to what Dörnyei and Ottó (1998) refer to as choice motivation, and the level of engagement in that process along with the factors shaping this level, or what Dörnyei and Ottó (1998) term executive motivation. Irrespective of whether a particular study is intended to look into the former, the latter, or both aspects, its design differs considerably from that of traditional cross-sectional research into motivation which typically provides just a snapshot of reasons for learning or the intensity of motivated learning behavior at a given time. This is because the need to capture changes in these areas necessitates obtaining at least two, but preferably more, sets of data from the same participants at different points, such as the beginning and end of an academic year, the induction into and termination of a language program, or the onset of language learning and many years on completion of formal education in this respect, a task that may pose a formidable challenge due to inevitable attrition of the participants. In this kind of research, data can be collected by means of questionnaires, such as the Attitude/Motivation Test Battery (Gardner, 2004) or surveys tapping different facets of L2 motivational self system (e.g., Ryan, 2009; Taguchi, Magid, & Papi, 2009), which can represent very different views of motivation, interviews, diaries, other types of narratives as well as various combinations of such tools, with triangulation possibly constituting the best option. As regards research focusing on motivational dynamics over shorter periods of time, such as language lessons or learning tasks, it is typically, but by no means exclusively, conducted within the framework of CDS theory and represents the socio-dynamic period in the study of motivation. Since, with rare exceptions (e.g., falling in love at first sight with a foreigner or being offered a job of our dreams in a foreign land), the motives for learning a foreign language do not change dramatically from one day to the next, empirical investigations of this kind focus on the ups and downs in motivational intensity, often operationalized as interest, engagement or involvement, as well as the factors responsible for such fluctuations (Pawlak, 2017). While access to participants is less of a problem here, research of this kind is confronted with its own share of challenges which are related in the main to collecting the requisite data, particularly if it is conducted during naturally occurring classroom interaction or the performance of tasks that are an integral part of a lesson. Such data can be gathered, for example, by means of learners’ self-ratings at predetermined time intervals in response to some auditory signal, a solution often employed by the present authors in their empirical investigations of motivation and one of its facets, willingness to communicate (e.g., Mystkowska-Wiertelak, 2016; Mystkowska-Wiertelak & Pawlak, 2017; Pawlak, 2012; Pawlak & Mystkowska-Wiertelak, 2015; Pawlak, Mystkowska-Wiertelak, & Bielak, 2014, 2016). This can be combined with post-class interviews, stimulated recall based on video recordings, questionnaires or immediate reports related to what transpired in a given class, or teacher-generated narratives concerning learners’ motivation. Difficulties related to data collection can be ameliorated to some extent in laboratory studies, such as those using idiodynamic software which allows second-by-second measurement of attributes under investigation (e.g., MacIntyre & Legatto, 2011; MacIntyre & Serroul, 2015). This research, however, suffers from the obvious lack of ecological validity because it would be imprudent to assume that, however motivation is operationalized, patterns observed in performing tasks in artificial situations would in all cases hold for similar tasks in language classes, where a complex interplay of internal and external factors comes into play. In the present section, an attempt is made to provide a necessarily brief and selective overview of previous studies of the dynamic nature of motivation in learning foreign and second languages. Such empirical evidence will be presented, first, with respect to research examining long-term changes in motives and motivational intensity, second, in relation to empirical investigations of moment-by-moment fluctuation in engagement, and, third, with regard to studies taking advantage of retrodictive qualitative modeling, an approach that was embraced in the present study and can be seen as to some extent reconciling different timescales in exploring the temporal dimension of motivation.

In one of the first studies focusing on motivational dynamics, Koizumi and Matsuo (1993) examined changes in the attitudes and motivations of 296 seventh-grade students learning English as a foreign langue over the period of one school year, finding a decrease in this respect until the third or seventh month, followed by a period of relative stabilization. They also uncovered that, with the passage of time, participants became more realistic about their goals, those with initially high ability in English language were more likely to retain positive attitudes and motivation over time, and girls consistently outperformed boys on most attitudinal and motivational variables. A gradual drop in the levels of motivation in the course of time was later reported in a number of studies undertaken in different educational contexts. For example, Tachibana, Matsukawa and Zhong (1996) showed that both Chinese and Japanese students tended to lose interest in learning English as they moved from junior to high school, whereas Inbar, Donitsa-Schmidt and Shohamy (2001) provided evidence for a slight drop on all motivational dimensions for learners of Arabic in Israel. In another study, Williams, Burden and Lanvers (2004) demonstrated on the basis of data collected by means of questionnaires and interviews from 228 students in Great Britain that L2 motivation tended to decline from Grade 7 to Grade 9, with the caveat that, again, girls were more motivated than boys and all the participants were more eager to study German than French. Somewhat more nuanced results were reported by Gardner, Masgoret, Tennat, and Mihic (2004), who examined the integrative motivation of Canadian university students in an intermediate-level French course over the period of one academic year. While the findings were similar to those of previous research in that the attitudes and motivation deteriorated from the fall to the spring, they also observed that such changes were twice as marked in the case of situation-specific motives than general motives, with the patterns of change being mediated by achievement. There are also studies that have mainly focused on changes in the quality of L2 motivation in terms of learners’ motives, goals, decisions and intentions rather than the magnitude of engagement. Ushioda (2001) conducted two interviews with 20 adult Irish learners of French, spaced 16 months apart, finding that during that period the participants were able to develop clearer goals with respect to the target language. Other researchers have explored the evolution of the nature of L2 motivation over much longer periods of time, going into two or more decades. Lim (2004), a Korean learner of English, for example, adopted an autobiographical approach in investigating his motivation over a twenty-year period, providing evidence for changes from the integrative to the instrumental orientation, and interaction with the learning environments. Shoaib and Dörnyei (2005) used interviews with 25 language learners to examine factors shaping motivational change as well as temporal patterns emerging from such change over twenty years, identifying six recurring themes (e.g., maturation and a gradual increase in interest in L2 learning, a period when no progress was being made, a move into a new phase of life). More recently, Hsieh (2009) found in his study of two Taiwanese learners pursuing an M.A. in the US that a six-month study abroad experience led to changes in their self systems with respect to goals, attitudes and L2 self-images in response to the contextual challenges they encountered. The study by Nitta and Asano (2010), in turn, reported fluctuations in choice and executive motivation of Japanese students over one year, which could be attributed to an interplay of social and interpersonal variables (e.g., teaching style, group dynamics). Finally, also worth mentioning is the quantitative investigation by Piniel and Csizér (2015), who showed little fluctuation in motivation during a 14-week writing course taught to 21 Hungarian students majoring in English, with the ideal L2 self and motivated learning behavior tending to be more stable than the ought-to self and learning experience.

Empirical evidence concerning changes in L2 motivation in the course of lessons or tasks is much more tenuous, which is perhaps the corollary of the difficulties involved in collecting the requisite data in real-time. In what is perhaps the first classroom-based study of this kind, Pawlak (2012) explored fluctuations in 28 Polish senior high school students’ motivation, operationalized as interest, involvement and persistence in the course of four regularly-scheduled lessons with the help of motivation grids which allowed self-assessment of involvement at five-minute intervals, questionnaires for teachers and learners, interviews with selected participants and detailed lesson plans. While no meaningful changes in motivational intensity were revealed between the classes, he reported some fluctuations in this respect within a lesson, which were tentatively attributed to “(…) not only the overall topic, the stage of the lesson or the task being performed, but also the place of this task in the overall lesson plan, the amount of novelty it involves, the phase of its execution, group dynamics, learner characteristics, as well as the priorities pursued by a group as a whole or individual students, with all of these internal and external variables constantly interacting (…)” (p. 273). Similar methodology was subsequently used in two research projects which were also conducted in the Polish context and involved senior high school students, but in both cases changes in motivational intensity from one lesson to the next and within single lessons were much more pronounced. Pawlak et al. (2014) investigated motivational change in 38 students in three intact groups during four naturally-occurring English classes and while they linked the observed fluctuations to the focus of the lesson, the nature of tasks and their length, transitions between different lesson stages, the opportunity to cooperate with others, and the relevance of what was being done to final examinations, they conceded that other factors must have been at play, such as, for example, individual difference variables, group dynamics, or rapport with the teacher. Kruk (2016), in turn, collected data during a total of 121 lessons in four intact groups over one semester, thereby considerably extending the longitudinal nature of this kind of research. He reported changes in motivation within and between lessons, but also periods of stability, which, however, were preceded or followed by abrupt decreases or increases in learner involvement, with the detected patterns being ascribed to a set of interrelated factors, including the lesson (e.g., topic, task, coursebook), the learners (e.g., age, ability, fatigue), and the school (e.g., the schedule). Motivational dynamics in the classroom was also the focus of the study carried out by Waninge, Dörnyei, and de Bot (2014), which involved 4 Dutch secondary school learners in six sections of German and Spanish lessons over the period of two weeks and in which the data were collected by means of classroom observations, questionnaires and the so-called motometers that enabled learners to indicate their level of motivation on a scale from 0 to 100 at five-minute intervals. As was the case with the studies mentioned above, the analysis provided evidence for “(…) considerable ups and downs and shifts within the learners’ motivational state within single classroom sessions” (p. 719), but these alternated with periods of relative stability in the case of some of the participants, trends that were ascribed to a constellation of individual and contextual factors. Of interest here is also the laboratory study by MacIntyre and Serroul (2015), who applied idiodynamic software (see above) with the purpose of tracing changes in approach and avoidance motivation of 12 undergraduate Canadian university-level learners of French in the performance of eight tasks. They found that variation in motivational ratings was a function of task difficulty but was mediated by a combination of cognitive and affective reactions (i.e., approach and avoidance motivation, perceived competence, anxiety and willingness to communicate).

As regards studies drawing on retrodictive qualitative modeling (see a description below), these are still few and far between, for the simple reason that the methodology is relatively novel to the field of SLA and it is only beginning to be harnessed by researchers. While RQM can be applied in the investigation of various individual differences variables, such as learners’ strategy use (Oxford, 2017) or teacher immunity (Hiver, 2016), it has first been employed in research on motivation. Chan et al. (2015) used RQM to investigate the motivational system’s signature dynamics in the case of secondary school students in Hong Kong and, with the help of six English teachers, identified seven learner archetypes, that is: a highly competitive and motivated student with some negative emotions, an unmotivated student with lower-than-average English proficiency, a happy-go-lucky student with low English proficiency, a mediocre student with little L2 motivation, a motivated distressed student with low English proficiency, a “perfect” English learner, and an unmotivated student with poor English proficiency. While the procedure allowed valuable insights into motivational processes, the researchers emphasized some methodological challenges, connected, among other things, with difficulty in finding students exactly fitting the archetypes, the need to include other data collection tools apart from interviews or problems involved in determining the nature of signature dynamics. In a more recent study, Kikuchi (2017) employed RQM to trace the motivational trajectories of 20 Japanese university freshmen over a ten-month period with a view to investigating the role of various motivators and demotivators inside and outside the classroom. Five distinct types were identified, with each of them following a different motivational pattern, viewing different factors as motivating and demotivating, and responding differently to contextual influences. Given the paucity of research on L2 motivation that would rely on RQM as well as its limited scope in terms of geographical location, educational level and program type, the study reported below aimed to make a contribution to this fledgling line of inquiry by identifying learner archetypes in Polish university students majoring in English and examining the development of motivational processes over time in the case of two of them representing quite diverse motivational systems.

3 The Study

Before the aims, design and findings of the study are presented, three important caveats are in order. First, the study is part of a larger-scale research project and even though, out of necessity, it makes references to its overall results with respect to the established archetypes, it focuses on motivational processes of only two English majors. Second, while RQM guided the collection and analysis of the data and this methodology was devised as a way of investigating complex dynamic systems, the research project is not grounded in CDS theory and does not attempt to interpret the findings within this framework, which is in line with the conviction that researching motivational dynamics should by no means be confined to a single theoretical position. Third, the main point of reference in the analysis of the data was the theory of L2 motivational self system and the key concepts it comprises, similarly to previous studies of L2 motivation conducted by one of the authors (Pawlak, 2016a, b).

3.1 Aims and Research Questions

The study was aimed to identify typical patterns among Polish university students majoring in English with respect to their motivation systems, to examine the motivational trajectories in the learning histories of selected students that led to the emergence of these patterns, and to uncover factors responsible for such motivational dynamics. Importantly, it investigated changes in the participants’ motivation both in terms of the motives driving them to study the target language, or choice motivation, the intensity of their motivated learning behaviors, which can be equated with executive motivation, and, to some extent, their reflections on and evaluation of previous learning, or motivational retrospection (Dörnyei & Ottó, 1998). More precisely, the following research questions were addressed:

-

1.

What archetypes can be identified among English majors with respect to motivational structure?

-

2.

What are the patterns for the development of these motivational systems in the learning histories of two students?

-

3.

What factors are responsible for the dynamic character of these motivational processes?

3.2 Participants

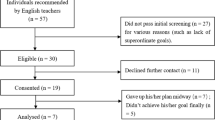

There were two groups of participants in the study, that is the teachers who identified archetypes among the students they taught in practical English classes and seven prototypical learners with whom interviews were conducted. When it comes to the former, most of them were experienced lecturers in the Faculty of Philology in a local Polish university, holding M.A. and Ph.D. degrees in English, who ran different components of an intensive course in English in a three-year B.A. program in English (e.g., grammar, speaking, writing). As regards the latter, they were enrolled in year 2 and 3 of the B.A. program which included the English course mentioned above, classes in linguistics, applied linguistics, foreign language pedagogy, history, literature and culture, and a number of electives, such as diploma seminars, most of which were taught through the target language.

As mentioned above, only two students are the focus of the analysis presented below and therefore more information is in order about these individuals, with the caveat that their real names are not revealed and pseudonyms are used instead. Anna, the first of the two participants, was 22 years old, she was interested in literature, film and culture, she had been learning English for 15 years at the time of the study and also reported learning or having learnt German, Russian and French, the last of these on her own. The other student, Mark, was 23 years of age, he was interested in English, music, movies and basketball, he had been learning English for 18 years and German for 10 years. It should be noted that he was truly fascinated with American culture and way of life and it was his dream to live in the US, with Scotland and the Scottish accent being other sources of fascination.

3.3 Procedures, Data Collection and Analysis

As elucidated above, the study employed the research procedure known as retrodictive qualitative modeling, which is only beginning to be applied to research on individual differences in language learning. Although a detailed discussion of this research template falls beyond the scope of this chapter and can be found in other publications (Chan et al., 2015; Dörnyei, 2014a), the idea is grounded in CDS theory and is aimed to pinpoint and analyze typical dynamic outcome patterns in learner motivation, understood as a complex dynamic system. According to Dörnyei (2014a, p. 90), “[t]his template aims to offer a systematic method of describing how the salient components within a dynamic system interact with each other to create unique development paths—or ‘signature dynamics’—that lead to system-specific outcomes as opposed to other possible outcomes”. This shares the assumptions underlying the empirical investigations reported earlier, namely that motivational processes occur on different timescales, different motives and goals can get the upper hand at different stages in language learning (e.g., integrative vs. instrumental, long-term or short-term), such changes are closely intertwined with fluctuations in motivational intensity, and both the choices made and the level of engagement hinge on amalgams of internal and external influences. However, it turns the traditional way of conducting research on its head by, first, examining the outcomes, or identifying learner archetypes in a given class or instructional setting, and, only at a later stage, examining the motivational trajectories that have led to the emergence of such outcomes. The application of RQM involves a three-step procedure as follows: (1) identification of salient student types in a particular group with the help of quantitative or qualitative procedures, such as cluster analysis, Q methodology (Irie, 2014), or social categorization, (2) identification of specific students who best fit in with the established archetypes and can thus be viewed as prototypical; such critical case sampling (Dörnyei, 2007) is followed by one or more semi-structured interviews, and (3) identification of the significant components of the motivational structure and the developmental patterns responsible for its emergence through qualitative analysis of the interview data. What should be underscored is that although the sequence of stages is rigid, the specific procedures employed at each of them are bound to vary from one study to another, depending on the number of participants, instructional contexts as well as researchers’ preferences.

In line with this template, the research project of which the present study is part consisted of three distinct phases. First, six teachers formed a focus group with the aim of establishing the archetypes within the entire student population attending the B.A. program in the Faculty of Philology. This involved a number of discussions in the whole group as well as in pairs, both in face-to-face meetings and e-mail exchanges, which, following the procedure adopted by Chan et al. (2015), focused on cognitive, affective, motivational and behavioral aspects of the students’ profiles. This resulted in the identification of seven student archetypes with respect to motivational systems, described by means of adjectives and nouns, as well as initial selection of 2-4 prototypical students that were representative of each archetype. In the second phase, critical case sampling took place as the teachers finally agreed on individuals that constituted the best fit for one of the archetypes, the selected students were requested to produce graphical representations of their self-perceived motivation to learn English over their learning histories, and they took part in semi-structured interviews which lasted from 35–70 min, depending on the extent to which a student was willing to share his or her experience. The interviews were conducted by four researchers, they were held in Polish to ascertain that the participants could precisely express their thoughts and feelings, and all of them were audio-recorded. In each case, the key point of reference was the motivation graph drawn by each participant, and, yet again, the themes revolved around cognitive, emotional, motivational and behavioral issues. When it comes to specific questions, at the outset they concerned general matters (e.g., interests) but also touched on critical episodes in the development of L2 motivation, which was followed by queries regarding clear-cut trends evident in the graphs, and, in the concluding part, motivating and demotivating factors as well as visions of themselves the students had as users of English in the future. In the final stage, the interviews were transcribed and subjected to qualitative content analysis, which was aimed to pinpoint the main components of the motivational systems and chart the developmental patterns which accounted for current motivational processes. As clarified above, in what follows such analysis will be presented for only two participants who, in the view of the researchers, could be assumed to differ quite considerably in regard to their motivational systems and trajectories that could be credited with generating them.

3.4 Findings

For the sake of clarity, the results of the study will be presented in two subsections: first, with respect to the seven archetypes identified by the focus group teachers, and, second, with regard to the two learner types selected for detailed analysis in this study, the cases of Anna and Mark. In the presentation of the two cases, the motivational profiles will be described at the outset, which will be followed by the discussion of the motivational trajectories and the factors shaping them.

3.4.1 Student Archetypes

The discussions conducted by the six focus group teachers, which, as was elucidated earlier, revolved around a combination of cognitive, affective, motivational and behavioral issues, led, after much deliberation, to the identification of seven archetypes in the population of English majors enrolled in the B.A. program. These archetypes were as follows:

-

A 1: A motivated, eager and positive student with relatively low proficiency in English.

-

A 2: A motivated student with considerable anxiety and low proficiency in English.

-

A 3: A motivated, conscientious and diligent student with high proficiency in English.

-

A 4: A poorly motivated and unambitious student with knowledge gaps, displaying traits of high self-confidence/esteem.

-

A 5: A student with little motivation and a natural ability to communicate.

-

A 6: A motivated and proficient student with some negative behavior.

-

A 7: An unmotivated, withdrawn student with relatively low English proficiency.

Since detailed discussion of all the seven motivational profiles together with the processes that led to their emergence would far exceed the confines of this chapter, a decision was made to undertake such analysis in relation to two archetypes. These are A3, standing for an English major that is highly motivated, diligent and possesses high proficiency in the target language, and A5, representing a student whose motivation is limited but who is at the same time endowed with a knack for communication in a foreign language. The decision to focus on these two types of students stemmed from the fact that they to some extent represented two opposing ends of the continuum with respect to their motivational systems, that is high versus low motivation and diligence versus natural ability, with the proficiency level being more or less comparable, at least with respect to communicative skills. In what follows, the motivational trajectories of Anna and Mark, students viewed as prototypical for the two archetypes, will be analyzed.

3.4.2 Motivational Profiles and Trajectories of the Two Prototypical Students

As regards aspects of Anna’s motivational profile that emerged from the discussions among the focus group teachers and resulted in nominating her as a prototypical manifestation of A3, the most important of them was that she was perceived as a motivated individual, strongly focused on attaining the goals that she set for herself. In cognitive terms, she was seen as a conscientious, diligent student, who was always willing to excel in class and worked hard at home, qualities that were in all likelihood responsible for her high proficiency in English. She exhibited high self-esteem, was self-confident, serious, calm and relaxed, and at the same time curious about things which were covered in class, well-organized and willing to cooperate with others. As she admitted in the interview, she made all the decisions concerning learning English on her own, she never had the opportunity to get the benefit of private tutoring and her parents were not involved in the process. All of this indicates that it is her ideal self rather than different aspects of her ought-to self that account for her desire to master the target language. She has a clear vision of herself as a proficient speaker of English, someone working as a teacher as she enjoys it a lot and perhaps doing a Ph.D. in English.

As illustrated in Fig. 1, which depicts Anna’s motivational trajectory from elementary school, when her adventure with English began, to the last year in the B.A. program, when the study was conducted, her motivation to learn English fluctuated to some extent over that time although a consistent upward trend is visible on graduation from junior high school. The first thing that can be observed from the graph is that her motivation at the beginning of elementary school was relatively low but then began two increase gradually, a change that can be attributed to the substitution of the teacher. As she commented, the teacher in the first grade was a “bad teacher”,Footnote 1 both in terms of the kind of instruction provided and personal traits, which engendered fear in everyone, and only when she was replaced in grade 2 did “real learning begin” and the motivation start to grow, although the focus remained on learning rules and the development of explicit knowledge. Apart from the change of the teacher, an important stimulus for learning at that time was a presentation that she attended on innovative ways of learning, in particular with respect to vocabulary, as this was the time when she recognized the utility of word cards, a strategy that she has been using ever since. As she emphasized, even in elementary school she was capable of self-assessment and was proud of the fact that she could excel in vocabulary learning in her class and, on the whole, she could feel that she was making more progress. This spike in motivation, however, began to gradually wear off as she entered junior high school, a situation which was, once again, attributable to the attitude of her teacher. More specifically, that teacher was young and inexperienced, treating the students as her peers and dedicated most of the class to gossiping about irrelevant matters rather than actual teaching. As a result, Anna was becoming increasingly bored and acutely aware of the lack of progress, which impelled her to do exercises on her own while others were wasting their time or simply waiting for the lesson to end. Still, she felt disappointed and more and more discouraged since she did not have an “authority” to fall back on, because homework assignments were not checked and tests were not administered. She was not convinced by the teacher’s assurances that her English was improving by the day as she had a feeling that she was wasting her time attending school classes and a fail would have been more motivating than giving up on the students.

The situation started to change once again with the transition from junior to senior high school, which can perhaps be attributed to the fact that, thanks to her own hard work and doing numerous tests, she passed the final exam with flying colors. In fact, her results were not only so superior that was she placed in the most advanced group but also served as a benchmark for assigning other students to different levels in terms of their proficiency in English. Enthralled as she was, the very first class in senior high came as a shock because the teacher spoke English all the time and she had the feeling that she was the only one that could not follow because of the low level of English instruction in junior high school. However, she was not ready to give up and decided to “clench her teeth”, carefully examining the materials used in class, searching for other sources on things that she could not understand, using the Internet to get in touch with people from other countries, as well as getting more and more cognizant of her errors because of regular use of a dictionary. At the same time she was fully aware of the progress that she was making because of the expertise and attitude of her teacher who was competent and demanding, spoke English all the time, was always prepared and made sure that the lessons were varied and interesting. A tangible sign of her growing mastery of English was the fact that she could talk to people from abroad and make herself understood, something that was confirmed when she went with her family to Prague, successfully ordering food or asking directions, achievements that made her proud of herself.

Despite these successes and shows of confidence, she intended to study Polish rather than English philology on completion of senior high school, a dream that she could not achieve for economic reasons, a situation which led to disappointment, frustration and a conviction that she was missing something important. In the end, however, she did not regret her decision to study English philology because as a result she was able to meet passionate and dedicated teachers, individuals that motivated and inspired her, which resulted in satisfaction and the belief that she was constantly developing both linguistically and intellectually. All of this happened despite a major setback that she suffered in the first year when she attended a plenary at an international conference organized by her institution, could not understand much of what the native speaker was saying and burst into tears. However, this event had a motivating rather than a demotivating effect and resulted in her considerably greater involvement in the process of learning English, which translated not only into her hard work in the courses she attended but also into her efforts to seek out opportunities for using English outside the classroom, participate in extra-curricular activities and be among students who volunteered to help out with the organization of future conferences.

As can be seen from the analysis of Anna’s motivational trajectory, a constellation of factors resulted in the emergence of her motivational profile that she manifested as a student in the last year of a B.A. program in English. On the one hand, it was her personal qualities, such as diligence, determination and perseverance, that resulted in her positive approach to the goals that she set for herself, and, on the other, it was the environment, both with respect to teachers and everyday life circumstances that guided the choices she made and had an impact on her involvement and engagement. What is important, however, these external influences, even when negative, not only did not dissuade her for pursuing her goals, but caused her to grin and bear it, and, in fact, in the long run, fueled her motivation to learn English and to diminish the distance between her current abilities and skills, and her vision of herself in the future, or her ideal L2 self.

Moving on to Mark as a prototypical student representing archetype A5 (little motivation but a natural ability to communicate), the focus group teachers saw him as unmotivated mainly because he was usually unprepared for classes and was uninvolved in them. This was evident on both affective and behavioral planes, as he openly displayed boredom and lack of interest in what was going on and refused to cooperate with the teacher and other students in his group, in some cases manifesting a rather unfriendly attitude. At the same time, the teachers regarded him as intelligent and they admitted that he was quite proficient in English, which they attributed to the fact that he relied on the knowledge and skills gained in senior high school and these were sufficient to successfully meet the demands of the course. While Mark, similarly to Anna, seems to have formed a clear vision of himself as a user of English in the future, not only is this vision different but the sources of motivation are dissimilar as well since he places store on what others think about him rather than what he thinks about himself. In other words, while his ideal L2 self seems to be critical in driving his efforts, the fuel for its realization is external and seems to reside in the extent to which other people admire him and are ready to follow his example.

As can be seen from Mark’s motivational trajectory, graphically represented in Fig. 2, he started learning English in kindergarten but it was just one hour a week and instruction took the form of game activities, with the effect that he was not even aware that he was learning and it is not really possible to talk about motivation at that time. The situation began to change with transition to elementary school because he soon noticed that he was top of his class in English, the teacher kept heaping praise on him, singled him out as a role model and encouraged him to take part in competitions. Mark loved the recognition he received and enjoyed being rewarded to the point of becoming somewhat conceited, with his motivation being resultative in nature, and being bred by his accomplishments and a constant desire to excel. When he went to junior high school, however, he was in for a rather unpleasant surprise as it turned out that other kids easily outperformed him, his grades dropped considerably and he realized that he may not have learnt as much in elementary school as he thought. A crucial episode which dramatically changed his opinion about his ability in English was a grammar test at the beginning of the first year which he failed, an event that surprised and stunned him because it was the first fail grade he had ever received. As a result he developed a negative attitude towards the teacher who was, in his view, very strict, mainly focused on grammar and paid little attention to whether or not someone had rich vocabulary or was good in communication. Entire lessons were devoted to doing grammar exercises in Xerox copies brought by the teacher and evaluation was predominantly grammar-based, with 90% of the grades resulting from grammar tests. In the words of Mark, “she tortured us with grammar. It was a nightmare”. He could not resist the feeling that his mastery of English was being blatantly underestimated and that the merely satisfactory (3 on a scale from 1 to 6) grade that he was awarded at the end of the school year did not do justice to his true abilities. He commented: “I had the impression that she was convinced I didn’t know English and I didn’t know grammar, and that was it. All the time I tried to prove, show I could communicate but it was pointless”. Still he wished he had learned more in elementary school as this could have allowed him to avoid the problems he faced. Although he admitted that he did learn a lot at the time, he was not involved in classroom activities and he did not seek opportunities for out-of-class communication, because he had to cram a lot for other subjects and, by his own admission, he is not “very hard-working by nature”. He did not get much support from his parents during this period because they did not seem to be concerned about him and attributed his lower grades to age problems. Looking back on learning English in junior high school, Mark insisted that he was still highly motivated to learn English and pinned the blame for the setbacks on the teacher. As he said during the interview, “the teacher was such that I could not do anything”.

His lack of involvement and reliance on what he had learned previously continued into senior high school where his L2 motivation was stable and moderate, and he, once again, “rested on his laurels”. There was a crucial difference in comparison with junior high school, however, since, although he felt that he could have invested more effort and his grades could have been better, as was the case in elementary school, Mark was again given as an example to his peers and earned their admiration, which served as a powerful motivator. When problems appeared, they were one more time related to insufficient knowledge of grammar which apparently was his Achilles’ heel. Once again, he was not very happy with his teacher who apparently did not pay attention to students and did not care much about them, but, much more importantly, failed to ensure ample opportunities for communicative practice, mainly focusing on various aspects of the linguistic system. In his view, teachers, including his English teacher, generated a lot of anxiety and stress in connection with the school-leaving examination, which may have been excessive given the challenge that this exam posed in reality, but had a very motivating effect on everyone. In contrast to junior high school, the parents were much more supportive at this stage, especially the father, and, to quote Mark, “(…) they liked that I was good in English and it was motivating”. Still, as he pointed out, had he a chance to go back to senior high school, he would have done much more to excel and stand out as this would have provided fuel for his motivation. Most importantly perhaps, it was at that time that he was beginning to form a vivid and concrete vision of himself in the future as someone going to the USA where he had a family, preferably Miami and Syracuse, and using English on an daily basis to communicate with native speakers. Although Mark did not comment on it in his interview, it was probably this vision that propelled him to take up English studies, a decision that was encouraged by his father.

Marks’ comments concerning his motivation at the university and the factors influencing it were much more extensive than those of Anna’s. First and foremost, he emphasized a major rise in motivation as he enrolled in the program, which he credited to the new context in which he had to function, enthusiastic teachers, the support of the parents, but also a tangible ideal self in the target language as someone having a job requiring regular use of English. This did not mean that he was still the best, as was the case in elementary and senior high school, as he had to repeat the second year and in general was not satisfied with his performance. While he was critical of some courses, such as British literature, where “there was too much information, problems were beginning to accumulate and in the end I got lost”, he experienced a major shock because other students were much less competitive than in junior and senior high school, they did not compare their grades with each other and they were focused on their own progress. In the course of his studies Mark became much more cognizant of the fact that learning a foreign language requires commitment, regular hard work and perseverance, things that were hard to come by, though, considering the fact that he was living in the dorm with all of its distractions. It is also interesting to point out that while he still cherished his senior high school vision of going to the USA, doubts started to appear, triggered by a growing realization that a diploma in English did not constitute guarantee of employment, whether in Poland or abroad. At the same time, he was full of admiration for those who had the courage to turn over a new leaf, leave everything behind and start a new life in a foreign land, which to some extent indicates that his vision of a user of English in the USA was still valid. What should be stressed is the fact that he was of the opinion that, although he did not have many opportunities to shine, his motivation was the highest at the university, and he was in fact ashamed when thinking of the opportunities that he may have wasted at previous educational levels.

Looking at Mark’s motivational trajectory, its seems clear that, in comparison to Anna, instead of deriving his strength from within himself, he was in obvious need of acceptance and admiration from others, which might testify to his extraverted personality. Even though it is still clearly possible to talk about the impact of an ideal rather than ought-to self, the vision was conditioned by the opinions of others that he more or less wittingly held in high esteem, mainly his teachers. However, this was only one source of his motivation because he also had a clear vision of what he wanted to do in the future, that is going to the US and communicating with native speakers, a goal that seemed to be distinct from the positive or negative evaluation that he may have received from his instructors. What should also be noted is the fact that his own assessment of L2 motivation was drastically disparate from that of the six focus group teachers, because he was apparently very motivated to learn English and quite cognizant of the mistakes he may have made, even if this did not show during the classes he attended.

4 Discussion

As shown in the analysis provided above, the application of RMQ yielded valuable insights into the L2 motivational self systems and processes of English majors and in-depth interviews with two of them offered evidence for temporal variation in L2 motivation and shed valuable light on factors that brought about such fluctuations. When it comes to the first research question, the procedure allowed for the identification of seven archetypes, characterized by quite distinct motivational patterns, which only to some extent overlapped those established in other studies using RMQ (e.g., Chan et al., 2015; Kikuchi, 2017), which should not come as a surprise given the differences in culture, age, educational level, type of program and overall proficiency. What should be emphasized, however, is that reaching a consensus on student types turned out to pose a formidable challenge, and, similarly to Chan et al. (2015), it was even more difficult to pinpoint students that would have constituted a perfect match for each of them. In fact, several candidates were identified in each case and the participating teachers were not unanimous about the final choices, which may indicate that the discussions should have been augmented with observations, learner narratives or interviews with more potential candidates.

Moving on to the second research question, the interview data together with the graphs produced by the students, provided unambiguous evidence for changes in their L2 motivational systems, both with respect to motives guiding them, levels of engagement, reflection on various aspects of the process of learning as well as visions of themselves as users of English in the future, or their ideal L2 selves. It should be stressed that although Anna and Mark represented two disparate archetypes, their motivational paths did not deviate from each other as much as could have been expected. In both cases, there was a visible spike in motivation in elementary school, followed by a dip in junior high school, which, incidentally, may indicate that there are problems with foreign language instruction at this level, and then yet another increase which has continued into the B.A. program. The only difference is connected with the fact that while Anna’s motivation began to climb steadily since she entered senior high school and this tendency has been maintained to the present day, in the case of Mark it remained stable for a longer period of time and only towards the end of senior high school could an upward trend be observed. Due to the nature of the data, it is not possible to compare the actual levels of engagement of the two students but it is clear that they have created vivid, if quite different, visions as users of English in the future and they are determined to move towards these ideal L2 selves, a fact that is understandable but by no means can be taken for granted in the case of English majors. What should alert teachers and researchers alike are the pitfalls of developing unfounded or downright false notions about the motivation of learners or research participants. This is because, unless we assume that he wished to paint a positive picture of himself in the interview, Mark was quite highly motivated, which stood in stark contrast to the archetype to which he was assigned, and his apparent lack of engagement in class may have stemmed from his disapproval of the instructional practices applied rather than his reluctance to study English. This goes to show how deceiving appearances can be and provides an additional argument for basing decisions about archetypes and prototypical learners representing them on more solid grounds than just the impressions or preconceived judgments of teachers.

With respect to the last research question, the factors that triggered changes in motivation were not dramatically different for the two students, being both internal and external in nature, although the consequences they produced were surely not the same. One such crucial influence was the teacher as a key element of learning experience, both in regard to his or her attitude, personality, involvement and the nature of instruction provided, which speaks to the fact that while school classes in and of themselves are insufficient to ensure mastery of a foreign language, they play an immense role in motivating or demotivating learners. As the two motivational trajectories demonstrate, they have the power to drastically alter learners’ involvement in the process of language learning, towards more positive and enthusiastic, as was the case with Anna when her first teacher in elementary school was substituted, or more negative and indifferent, as when Mark’s communicative skills were ignored after he started attending junior high school. Two other important factors, admittedly much more so in the case of Mark than Anna, are peers and parents, as the former can become a kind of an audience in front of which one’s language abilities can be displayed and the latter can provide the necessary support or, alternatively, fail to do so. Yet another pivotal influence on L2 motivation turned out to be critical moments in the learning histories of both learners, not as much the positive ones as those unpleasant that constituted a rude awakening, such as difficulty in understanding the teacher, a failed grammar test or inability to follow a plenary at a conference. What matters, though, was the response to these influences which was heavily dependent on the two students’ personality, a variable that in some cases trumped the impact of other factors. While Anna was introverted, had an internal locus of control and internal attributions, which allowed her to persevere despite all the setbacks she may have experienced, Mark was visibly extraverted, exhibited an external locus of control and external attributions, craving admiration and praise as well as easily doubting his abilities in the face of adversity (see Ehrman, Leaver, & Oxford, 2003, for discussion of these concepts). Although they appear to have made the right choice in studying English philology and can envisage a well-defined path ahead of them, their personalities still play a critical role, which is evident, for example, in the fact that Mark has more misgivings about his future than Anna. What also shaped the motivational trajectories of the students was motivational retrospection, which appeared to have positive consequences for Anna, but less so for Mark, who, instead of looking to the future, ruminated excessively on what he could have done differently in the past.

5 Conclusion

The present chapter has presented partial results of what is, to the best knowledge of the authors, the first attempt to apply retrodictive qualitative modeling to the study of L2 motivation in the Polish educational context. Although the focus has been on the motivational trajectories of only two English majors representing two different archetypes with respect to motivational systems, the study constitutes an important contribution to the scant existing literature on the application of RQM to research on motivation and focuses on contexts, proficiency levels and programs that have not yet been examined with the help of this procedure. Obviously, for the picture to become more complete, the analysis of the motivational trajectories of the remaining students is necessary. However, even at this early stage it appears warranted to assume that the process of identifying archetypes and selecting students that fit them best should draw on more reliable data sources than outcomes of discussions among teachers that are somewhat inevitably tinted by their impressions about learners, founded on one-off occurrences or erroneous judgments and thus failing to do justice to reality. For this reason, as postulated by Chan et al. (2015), future research should employ additional data collection tools, such as observations, interviews with past teachers or analyses of available documentation, but also ensure that interviews are conducted with a greater number of candidates for a given archetype so that the best possible fit can be achieved. A separate issue is the extent to which findings of such research can inform everyday classroom pedagogy, in this case the manner in which the intensive course in English is planned and taught in the B.A. program. While suggestions of this kind can only be tentative at this juncture, it would appear that awareness of motivational profiles would enable teachers to better cater to the needs of individual students and, to refer to another novel line of inquiry in motivational research, to be better able to generate in them what has come to be known as directed motivational currents, or periods of intense involvement that can support long-term motivation to learn a foreign language (Dörnyei, Henry, & Muir, 2016). Given this potential, there is surely a need for more research utilizing RQM, with the important caveat that such empirical investigations do not have to be confined to the theoretical perspective from which this set of empirical procedures has originated.

Notes

- 1.

All the translations of the excerpts from the interview included in this chapter were made by the researchers.

References

Chan, L., Dörnyei, Z., & Henry, A. (2015). Learner archetypes and signature dynamics in the language classroom: A retrodictive qualitative approach to studying L2 motivation. In Z. Dörnyei, P. D. MacIntyre, & A. Henry (Eds.), Motivational dynamics in language learning (pp. 238–259). Bristol, Buffalo and Toronto: Multilingual Matters.

Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in second language acquisition. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 motivational self system. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the self (pp. 9–42). Bristol, Buffalo and Toronto: Multilingual Matters.

Dörnyei, Z. (2014a). Researching complex dynamic systems: ‘Retrodictive qualitative modelling’ in the language classroom. Language Teaching, 47, 80–91.

Dörnyei, Z. (2014b). Future self-guides and vision. In K. Csizér & M. Magid (Eds.), The impact of self-concept on language learning (pp. 7–18). Bristol, Buffalo and Toronto: Multilingual Matters.

Dörnyei, Z. (2014c). Motivation in second language learning. In M. Celce-Murcia, D. M. Brinton, & M. A. Snow (Eds.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (4th ed., pp. 518–531). Boston, MA: National Geographic Learning/Cengage Learning.

Dörnyei, Z., Henry, A., & Muir, C. (2016). Motivational currents in language learning: Frameworks for focused interventions. New York: Routledge.

Dörnyei, Z., MacIntyre, P., & Henry, A. (2015). Motivational dynamics in language learning. Bristol, Buffalo and Toronto: Multilingual Matters.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ottó, I. (1998). Motivation in action: A process model of motivation. Working Papers in Applied Linguistics, 4, 43–69.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ryan, S. (2015). The psychology of the language learner revisited. New York and London: Routledge.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2011). Teaching and researching motivation (2nd ed.). Harlow: Pearson Education.

Ehrman, M. E., Leaver, B. L., & Oxford, R. (2003). A brief overview of individual differences in second language learning. System, 31(3), 313–330.

Gardner, R. C. (2004). Attitude/motivation test battery: International AMTB research project. Canada: The University of Western Ontario.

Gardner, R. C., Masgoret, A.-M., Tennant, J., & Mihic, L. (2004). Integrative motivation: Changes during a year-long intermediate-level language course. Language Learning, 81, 344–362.

Henry, A. (2015). The dynamics of possible selves. In Z. Dörnyei, P. D. MacIntyre, & A. Henry (Eds.), 2015. Motivational dynamics in language learning (pp. 83–94). Bristol, Buffalo and Toronto: Multilingual Matters.

Hiver, P. V. (2016) Tracing the signature dynamics of language teacher immunity. Ph.D. thesis, University of Nottingham.

Hsieh, Ch-N. (2009). L2 learners’ self-appraisal of motivational changes over time. Issues in Applied Linguistics, 17, 3–26.

Inbar, O., Donitsa-Schmidt, S., & Shohamy, E. (2001). Students’ motivation as a function of language learning: The teaching of Arabic in Israel. In Z. Dörnyei & R. Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and second language acquisition (pp. 297–311). Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press.

Irie, K. (2014). Q methodology for post-social-turn research in SLA. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 4, 13–32.

Kikuchi, K. (2017). Reexamining demotivators and motivators: A longitudinal study of Japanese freshmen’s dynamic system in an EFL context. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 11, 124–145.

Koizumi, R., & Matsuo, K. (1993). A longitudinal study of attitudes and motivation in learning English among Japanese seventh grade students. Japanese Psychological Research, 35, 1–11.

Kruk, M. (2016). Temporal fluctuations in foreign language motivation: Results of a longitudinal study. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 4, 1–17.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2015). Ten ‘lessons’ from Complex Dynamic Systems Theory: What is on offer? In Z. Dörnyei, P. D. MacIntyre, & A. Henry (Eds.), Motivational dynamics in language learning (pp. 11–19). Bristol, Buffalo and Toronto: Multilingual Matters.

Larsen-Freeman, D., & Cameron, L. (2008). Complex systems and applied linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lim, H. Y. (2004). The interaction of motivation, perception, and environment: One EFL learner’s experience. Hong Kong Journal of Applied Linguistics, 7(2), 91–106.

MacIntyre, P. D., & Legatto, J. J. (2011). A dynamic system approach to willingness to communicate: Developing an idiodynamic method to capture rapidly changing affect. Applied Linguistics, 32, 149–171.

MacIntyre, P. D., & Serroul, A. (2015). Motivation on a per-second timescale. Examining approach-avoidance motivation during L2 task performance. In Z. Dörnyei, P. D. MacIntyre, & A. Henry (Eds.), Motivational dynamics in language learning (pp. 109–138). Bristol, Buffalo and Toronto: Multilingual Matters.

Mystkowska-Wiertelak, A. (2016). Dynamics of classroom WTC: Results of a semester study. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 6, 651–676.

Mystkowska-Wiertelak, A., & Pawlak, M. (2017). Willingness to communicate in instructed second language acquisition: Combining a micro- and macro-perspective. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Nitta, R., & Asano, R. (2010). Understanding motivational changes in EFL classrooms. In A. M. Stoke (Ed.), JALT 2009 Conference Proceedings (pp. 186–196). Tokyo: JALT.

Oxford, R. L. (2017). Teaching and researching language learning strategies: Self-regulation in context. London and New York: Routledge.

Pawlak, M. (2012). The dynamic nature of motivation in language learning: A classroom perspective. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 2, 249–278.

Pawlak, M. (2015). Review of Zoltán Dörnyei, Peter D. MacIntyre, and Alastair Henry’s Motivational dynamics in language learning. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 5, 707–713.

Pawlak, M. (2016a). Investigating language learning motivation from an ideal language-self perspective: The case of English majors in Poland. In D. Gałajda, P. Zakrajewski, & M. Pawlak (Eds.), Researching second language acquisition from a psycholinguistic perspective. Studies in honor of Danuta Gabryś-Barker (pp. 63–59). Heidelberg and New York: Springer.

Pawlak, M. (2016b). Another look at the L2 motivational self system of Polish students majoring in English: Insights from diary data. Theory and Practice of Second Language Acquisition, 2(2), 9–26.

Pawlak, M. (2017). Dynamiczny charakter motywacji w nauce języka obcego. Perspektywy badawcze [The dynamic nature of motivation in learning a foreign language: Research directions]. In A. Stolarczyk-Gembiak & M. Woźnicka (Eds.), Zbliżenia: Językoznawstwo – translatologia [Encounters: Linguistics – translatology] (pp. 115–128). Konin: Wydawnictwo PWSZ w Koninie.

Pawlak, M., & Mystkowska-Wiertelak, A. (2015). Investigating the dynamic nature of L2 willingness to communicate. System, 50, 1–9.

Pawlak, M., Mystkowska-Wiertelak, A., & Bielak, J. (2014). Another look at temporal variation in language learning motivation: Results of a study. In M. Pawlak & L. Aronin (Eds.), Essential topics in applied linguistics and multilingualism. Studies in honor of David Singleton (pp. 89–109). Heidelberg and New York: Springer.

Pawlak, M., Mystkowska-Wiertelak, A., & Bielak, J. (2016). Investigating the nature of classroom WTC: A micro-perspective. Language Teaching Research, 20(5), 654–671. doi:10.1177/1362168815609615.

Piniel, K., & Csizér, K. (2015). Changes in motivation, anxiety and self-efficacy during the course of an academic writing seminar. In Z. Dörnyei, P. D. MacIntyre, & A. Henry (Eds.), Motivational dynamics in language learning (pp. 164–194). Bristol, Buffalo and Toronto: Multilingual Matters.

Ryan, S. (2009). Self and identity in L2 motivation in Japan: The ideal L2 self and Japanese learners of English. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 98–119). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Shoaib, A., & Dörnyei, Z. (2005). Affect in life-long learning: Exploring L2 motivation as a dynamic process. In P. Benson & D. Nunan (Eds.), Learners’ stories: Difference and diversity in language learning (pp. 22–41). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tachibana, Y., Matskukawa, R., & Zhong, Q. X. (1996). Attitudes and motivation for learning English: A cross-national comparison of Japanese and Chinese high school students. Psychological Reports, 79, 691–700.

Taguchi, T., Magid, M., & Papi, M. (2009). The L2 motivational self system among Japanese, Chinese and Iranian learners of English: A comparative study. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 120–143). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Ushioda, E. (2001). Motivation as a socially mediated process. In Z. Dörnyei & R. Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and second language acquisition (pp. 91–124). Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press.

Ushioda, E., & Dörnyei, Z. (2012). Motivation. In S. M. Gass & A. Mackey (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 396–409). London and New York: Routledge.

Waninge, F., Dörnyei, Z., & de Bot, K. (2014). Motivational dynamics in language learning: Change, stability, and context. Modern Language Journal, 89, 704–723.

Williams, M., & Burden, R. (1997). Psychology for language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Williams, M., Burden, R., & Lanvers, U. (2002). ‘French is the language of love and stuff’: Student perceptions of issues related to motivation in learning a foreign language. British Educational Research Journal, 28, 503–528.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to take this opportunity to thank the focus group teachers and the students who participated in the study, but in particular our friends and colleagues from State University of Applied Sciences in Konin, Poland, who were involved in the research project that yielded data for the study described in this chapter: Dr. Jakub Bielak, Dr. Marek Derenowski, Dr. Katarzyna Papaja and Dr. Bartosz Wolski.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Pawlak, M., Mystkowska-Wiertelak, A. (2018). Tracing the Motivational Trajectories in Learning English as a Foreign Language. The Case of Two English Majors. In: Pawlak, M., Mystkowska-Wiertelak, A. (eds) Challenges of Second and Foreign Language Education in a Globalized World. Second Language Learning and Teaching. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66975-5_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66975-5_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-66974-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-66975-5

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)