Abstract

This chapter presents benefits and drawbacks of using humor in learning/for teaching and training. We introduce two theories about humor and learning, namely the Instructional Humor Processing Theory and the Perceived Humor Hypotheses. Among the consequences of humor in instruction are cognitive, social, as well as motivational and affective ones: Humor may enhance learning if tied to the course content, humor may increase teachers’ immediacy and the presenters’ likability, and humor may foster positive affect and thus motivation. However, it may reduce the perceived credibility of the presenter and does not necessarily improve effectiveness or performance. Also, the use of humor interacts with personality. We present findings about the mode of presentation, that is, about the use of humor in textbooks, tests, and online instruction. Research in school/university settings serves as the basis and nearly the only setting of previous research; we discuss the limited research on instruction in work contexts. Future research avenues as well as recommendations for practical use close this chapter. For instance, techniques recommended for teaching students (e.g., smile, relate humor to important information) can be applied to trainings or instruction in the work context.

The original version of this chapter was revised: See the “Chapter Note” section at the end of this chapter for details. The erratum to this chapter is available at https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65691-5_9

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Learning

- Instructional Humor Processing Theory

- Memory

- Creativity

- Immediacy

- Credibility

- Motivation

- Affect

- Textbooks

- Online classrooms

6.1 Introduction

Research on the use of humor in workplace learning and training contexts is rare, even though formal or informal learning is an important activity in many workplaces. Thus, we provide a review of the use of humor in school or university teaching (adult settings). Several of these empirical findings may be applicable to the work context. Also, “teacher” and “college instructor” are professions and thus represent specific work contexts.

Several reviews on humor in school exist. Neuliep (1991) presented an extensive review of the findings through 1990. Also, in Martin’s book (2007), a chapter on the use of humor in the classroom provides a comprehensive summary. Recently, Banas, Dunbar, Rodriguez, and Liu (2011) reviewed the knowledge of four decades of research on the use of humor in instruction. We will summarize these reviews with regard to findings useful for the work context, and discuss the limited research that has been conducted in applied work contexts. Knowledge about humor in classroom instruction might be appropriately transferred to professional (work) contexts, as suggested by the title of Berk’s (1998) book about how to use humor in instruction: “Professors are from Mars, students are from Snickers: How to write and deliver humor in the classroom and in professional presentations.”

6.2 Content and Frequency of Humor in Instruction

Content Teachers have been found to use humor in the classroom in a variety of ways, a considerable proportion being tendentious (Gorham & Christophel, 1992; Neuliep, 1991). Among the contents of teachers’ humor in the classroom were personal/general anecdotes or stories, humor that was related or unrelated to the subject or topic, joke telling, brief humorous comments, self-disparaging humor, and unplanned humor (Neuliep, 1991; Wanzer, Frymier, Wojtaszczyk, & Smith, 2006) or offensive and other-disparaging types (Frymier, Wanzer, & Wojtaszczyk, 2008). Most often, funny stories, funny comments, jokes, and professional (positive) humor were used, as indicated by students as well as (three) professors (Torok, McMorris, & Lin, 2004). In a taxonomy of classroom humor, Neuliep (1991) came up with five categories, which are teacher-targeted humor (e.g., self-disclosure-related), student-targeted humor (e.g., error identification), untargeted humor (e.g., awkward comparison/incongruity), external source humor (e.g., historical incident), and nonverbal humor (e.g., affect display humor). These taxonomies differ in their level of abstraction, for instance, the content of humor or the person(s) it is directed at. Summing up, humor is as multifaceted in learning contexts as it is in other areas of life.

Frequency Banas et al. (2011) concluded that the frequency of humor was highly dependent on the measure (e.g., self-report vs. tape recordings). From analyzing responses of US high school teachers, Neuliep (1991) found an average frequency of two humorous attempts per session. In a study of US undergraduates, 60% reported that their professors always used humor and 70% indicated strong agreement that their professor was entertaining and witty (Torok et al., 2004). College instructors seem to use more humor than school teachers (Banas et al., 2011). However, most studies are outdated and conducted in single contexts. Given that most studies were conducted in the US, differences in humor frequency due to cultural norms are largely unknown.

6.3 Theories About Humor in Instruction

The three general theoretical approaches of humor, as introduced in Sect. 2.3, are also applicable to humor in learning and training contexts. Thus, humor in classrooms is based on incongruity and may lead to arousal in humor recipients. As far as learning takes place in a social context, superiority issues may be related to the use of humor. However, there are two approaches specifically referring to the learning and instruction context. Thus, in the following we introduce the Instructional Humor Processing Theory (IHPT) and the Perceived Humor Hypothesis. While the IHPT proposes a process model based on incongruity theory, the Perceived Humor Hypothesis states that the advantage of humorous material for memory is based on the perception of humor rather than incongruity.

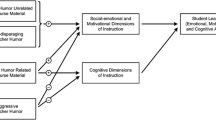

Instructional Humor Processing Theory Introduced by Wanzer, Frymier, and Irwin (2010), the IHPT combines incongruity-resolution theory, disposition theory, and the elaboration likelihood model (ELM) of persuasion. Wanzer et al. (2010) explained why the humor of certain types of instructors may result in increased student learning, whereas the humor of others does not. First, students have to recognize incongruity in an instructor’s message, and they must then resolve or interpret this incongruity. Otherwise, the message is non-humorous, confusing, or distracting. Given that the humor is perceived, its appropriateness is then judged. Appropriate humor (e.g., affiliative) results in positive affect, whereas inappropriate humor (e.g., disparaging) results in negative affect. ELM predicts that this positive affect motivates students to elaborate and process the humorous message, given that the humorous material enhances the ability to process (e.g., if it is related to course content), and thus learning and retention will be enhanced. Negative affect will more likely reduce motivation and the ability to process because it distracts students. In aiming to test the IHPT in a cross-sectional study including 292 US students, Goodboy, Booth-Butterfield, Bolkan, and Griffin (2015) reported that instructor humor was positively related to students’ cognitive learning, extra effort, participation, and out-of-class communication—even when controlling for students’ learning and grade orientations. However, Bolkan and Goodboy (2015) tested the IHPT against self-determination theory (SDT) with a sample of 300 US students. They found the indirect effect of humor on perceived cognitive learning through SDT higher than through IHPT. Thus, humor was effective through the fulfillment of the students’ basic psychological needs according to SDT (i.e., autonomy, competence, relatedness) and not so much through the (motivating) increase in positive affect the IHPT states.

The Perceived Humor Hypothesis Carlson (2011) dissents with the IHPT in that he states that the positive effect of humor for memory is based on the very perception of humor rather than semantic elaboration or incongruity resolution. Carlson (2011) compared the assumptions about (1) semantic elaboration, (2) incongruity resolution, and (3) humor perception with related findings: (1) Differential semantic processing is central to the context-dependent elaboration hypothesis, meaning that more stored semantic knowledge—or a greater memory search—is needed for humorous than non-humorous material, resulting in greater recall. So recall is not about humor per se. However, Schmidt and Williams (2001) reported that the effects of humor were not due to increased rehearsal (though humor showed effects in intentional and incidental memory situations), thus challenging the importance of semantic elaboration. (2) Semantic incongruity creates a memory advantage for humorous materials due to the (incongruity)-resolution found by a semantic search. However, Schmidt (1994) reported that the effects of humor could not be explained by contextual surprise (even if expected humor effects emerged). Thus, the importance of incongruity resolution for the positive effect of humor on memory is objected. (3) The final assumption states that perceiving humor increases recall; that is, the successful resolution of incongruity must be perceived as humorous in order to be recalled better. In fact, retrieval processes seem to be influenced by humor: items that are recalled earlier in free recall situations had higher humor ratings (Schmidt, 2002). Thus, Carlson (2011) concluded that the positive effect of humor for memory is exclusively based on the perception of humor. In line with his reasoning, Carlson’s (2011) own study involving Chilean students’ ratings of humor suggested that only perceived humor explained the advantage in recall offered by humor (in contrast to inspiration), but neither semantic elaboration nor incongruity resolution did. Thus, whether or not the latter two mechanisms are significant for the recall advantage deserves further investigation. However, the perception of humor seems to be crucial for the positive memory effects of humor.

6.4 The Consequences of Humor in Instruction

Humor is said to have cognitive, social, and psychological (i.e., emotional) benefits on learning in college classrooms from the instructors’ perspective (Lei, Cohen, & Russler, 2010). However, most propositions found mixed support in studies on university student samples, and very few studies were ever conducted in the work context. Moreover, some ways of using humor are associated with drawbacks. Thus, degrading remarks about students (especially if unrelated to the course), offensive humor (e.g., sexual, cynical), and excessive humor may be problematic in learning contexts (Lei et al., 2010).

In the following, we present empirical findings regarding cognitive, social, and psychological effects in learning. Most of the research was conducted in classrooms.

6.4.1 Cognitive Effects of Humor on Learning

Humor is used instrumentally to foster learning (Martin, 2007). The cognitive (i.e., educational) benefits consist of enhancing interest (including interest in boring subjects), increasing attention and motivation, elevating students’ self-competence, as well as facilitating comprehension, creativity, problem-solving, and risk-taking (Lei et al., 2010; Neuliep, 1991). Accordingly, in their seminal study, Bryant, Comisky, Crane, and Zillmann (1980) found that (male) teachers’ use of humor in tape-recorded class presentations was associated with students’ perceived general effectiveness of teaching, especially when the humor was spontaneous as compared to prepared humor.

On the other hand, excessive humor may make students feel self-conscious or bored or lose focus on the content of the course (Lei et al., 2010). Even more important, humor may lead to misunderstandings, which cause distorted recall. This might be especially relevant when intelligence is low and thus understanding is impaired (e.g., for irony) or when cultural backgrounds differ and the frame of reference leads to different perceptions and appraisals of humor.

Memory, Attention, and Learning Attention (e.g., Zillmann, Williams, Bryant, Boynton, & Wolf, 1980), learning, and memory are said to be better with humor, especially when humor is related to the course.

Studies with experimental designs found evidence for beneficial memory effects of humor. Students’ retention 6 weeks after viewing a lecture was superior for students in the topic-related humor condition than in the non- or unrelated humorous conditions (Kaplan & Pascoe, 1977). Also, Chilean students’ ratings of humor in photographs, keywords, and phrases predicted recall performance (Carlson, 2011). However, only the recognition but not the recall performance of 165 US students was better when videos were humorous and relevant to the lecture material (Suzuki & Heath, 2014). Also, Schmidt (1994) largely supported the link between humor and memory: Humorous sentences were remembered better than non-humorous sentences in a variety of conditions (Schmidt, 1994) because humor increased attention and rehearsal relative to or at the expense of non-humorous material. The subjectively perceived humor of the sentences affected memory (Schmidt, 1994).

In contrast to studies with experimental designs, self-reported learning found mixed support for beneficial memory effects of humor. That is, three cross-sectional studies report contradictory results about students’ self-assessed learning. Wanzer et al. (2010) found that course-related humor correlated with students’ learning, especially teachers’ self-disparaging humor. However, humor unrelated to the course and inappropriate forms of humor (i.e., offensive) were unrelated to learning, thus indicating the ambiguous (or context-dependent) role of this type of humor. Likewise, professors’ use of humor helped students learn better (40% said often, 40% always)—however, students’ perceptions of competence, effectiveness, and learning were unrelated to professors’ use of humor (Torok et al., 2004). Furthermore, humor was not significantly related to students’ affect toward the course and their cognitive learning in a study of 286 US students (Myers, Goodboy, & Members of COMM 600, 2014).

In conclusion, humor should be used for enhancing learning, but should be closely tied to the content of the course materials and rather be used infrequently in order to illustrate the most important content (Martin, 2007).

Performance and Creativity The supports for the effects of dispositional humor in instruction are sparse and inconsistent: Sense of humor was correlated with the intelligence, retention, and creativity of elementary school children (Hauck & Thomas, 1972). However, humor styles were not related to Belgian students’ school performance (Saroglou & Scariot, 2002).

More studies about humor and performance as well as creativity were conducted with regard to humor exposure. In an experiment in higher education, Ziv (1988) found that, in a 14-week statistics course, an intervention group with course-relevant humor exhibited superior learning, that is, higher scores on the final exam, over the control group without humor. A second experiment replicated these findings (Ziv, 1988). Two experiments with 124 Australian students showed that exposure to humor increased persistence in two tasks (via amusement), and the humor–persistence link was stronger for persons higher in self-enhancing humor (Cheng & Wang, 2014). This underlines the self-regulative function of humor and provides further explanations for the persistence path of the Dual Pathway to Creativity Model (Nijstad, De Dreu, Rietzschel, & Baas, 2010). This model proposes that creativity is a function of cognitive flexibility and cognitive persistence. Thus, creativity may be influenced by personality or situation features through effects on either flexibility or persistence, or both (Nijstad et al., 2010). In an experiment with 80 US students, jokes and simple sentences of high or low imagery were presented prior to participants’ attempts to solve tasks: Humor increased the speed of mental rotation (i.e., imaginal tasks) and slowed performance on analogies (i.e., verbal tasks) for men but not for women (Belanger, Kirkpatrick, & Derks, 1998). So, humor exposure may foster or hinder performance, but this might depend on gender.

Drawing on earlier research by Isen, Daubman, and Nowicki (1987) and Ziv (1976), Scheel, Bachmann, Gerdenitsch, and Korunka (2015) found that affect induction with four video conditions was more strongly related to mens’ verbal creativity than to womens’: In this experiment with 165 German/Austrian students, only the induction of positive affect with humor was associated with higher verbal creativity (fluency, appropriateness, flexibility, but not originality), but the inductions of neutral, negative, or positive non-humorous affect were not (Scheel et al., 2015). Filipowicz (2006) reported similar gender-dependent findings, with mens’ creative performance being enhanced by positive affect induction but not womens’. He explained that different arousal levels might account for this finding (i.e., only men had higher arousal through positive affect) and concluded that pleasantness and activation may be necessary for positive affect to foster creativity. The role of humor was further highlighted when surprise—the inherent characteristic of humor—was found to fully mediate the relation between positive affect induction and creativity (Filipowicz, 2006). While these findings underscore the impact of positive affect on (creative) performance, direct evidence for the beneficial effects of humor in instruction on creativity is largely missing. Again, humor may be more enjoyable and may thus enhance motivation or activation.

6.4.2 Social Effects of Humor

According to Lei et al. (2010), the social benefits (i.e., relationships with students) of humor use include improvements in student morale, the establishing of professional relationships with students, the building of a sense of trust, fear and tension reduction, approachableness of the instructor, and creating a relaxed and positive learning climate. It also serves other interpersonal, social communication functions (e.g., status maintenance, norm enforcement; Martin, 2007). However, hostile forms of humor are caveats (Martin, 2007; Torok et al., 2004). For instance, ridiculing a student may serve the short-term goal of enforcing norms and correcting students’ behavior (e.g., Bryant, Brown, Parks, & Zillmann, 1983) but has long-term detrimental effects on classroom climate (e.g., Janes & Olson, 2000).

Students appreciate a professors’ use of humor (Bryant et al., 1980; Torok et al., 2004). However, humor might threaten credibility perceptions. While an older study did not find a significant relation between humor ratings and competence perceptions (Bryant et al., 1980), two more recent studies report contradictory results. That is, advisors’ humor was positively related to advisee perceptions of advisor credibility (Wrench & Punyanunt-Carter, 2005). However, in an experiment with Canadian students, humorous individuals were seen as less intelligent and trustworthy (Bressler & Balshine, 2006). Also, excessive humor may jeopardize the credibility of the instructor (Lei et al., 2010; see also Bressler & Balshine, 2006; Bryant, Brown, Silberberg, & Elliott, 1981).

Among the most intensely discussed social consequences in the learning context are immediacy and empathy of the instructors; thus, we present findings regarding both constructs. Again, no studies in the work context exist.

Immediacy and Empathy Humor appears to belong to the broader set of teacher behaviors that contribute to a perception of immediacy in the classroom, which enhances students’ evaluations of teachers and courses and perceived learning (Wanzer & Frymier, 1999). Immediacy behavior reduces psychological distance and enhances closeness between students and their teachers (Neuliep, 1991). Thus, immediacy is said to ensure that classes remain semiformal (Neuliep, 1991).

Both amount and type of humor are important for classroom climate (Stuart & Rosenfeld, 1994). Thus, low overall teacher humor was seen as less supportive by students. Offensive and hostile teacher humor is perceived as inappropriate (Frymier et al., 2008), defensive, and less supportive (Stuart & Rosenfeld, 1994).

On the other hand, students perceived professors as more caring when professors used humor, and the majority of the students thought that humor promotes a sense of community (Torok et al., 2004). Also, teachers’ level of humor orientation, verbal aggressiveness, and nonverbal immediacy were related to students’ ratings of teacher humor (Frymier et al., 2008). These studies focused on teachers as the producers of humor (“sender”). Additionally, the higher the students’ own humor orientation and communication competence, the more appropriate they perceive the teacher humor (Frymier et al., 2008).

Though students’ empathy was positively related to students’ own positive, adaptive use of humor, and negatively to aggressive humor (but not to self-defeating humor, Hampes, 2010), there is no study about humor and empathy perceptions of teachers. Overall, the studies mentioned in this section relied on cross-sectional self-reports from US university students. Whereas benign humor (e.g., affiliative, self-enhancing) seems to be favorable for immediacy, other-disparaging humor (e.g., aggressive, offensive) tends to show the opposite effect.

6.4.3 Motivational and Affective Effects of Humor

Among the psychological benefits, Lei et al. (2010) and Neuliep (1991) saw enhancements of students’ well-being (including mental and physical health), self-image, and self-esteem; an increased ability to cope with stress; anxiety/tension reduction; and the reversion of negatively conditioned feelings. Also, humor may reduce apprehension around potentially uncomfortable topics (e.g., sex education, Allen, 2014). In the following, we present empirical findings on motivation, affect, and appraisal.

Motivation Motivation may play an important role in why humor may be related to learning; the impact of teachers’ (humorous) behavior seems relevant for motivation. Though they did not directly assess humor, two studies found a relation between teachers’ immediacy and students’ learning via motivation: Immediacy (e.g., verbal: uses humor in class; nonverbal: smiles at the class while talking) and students’ state motivation had a combined impact on learning (Christophel, 1990). Also, state motivation mediated, but only the relation between verbal immediacy and affective learning (Frymier, 1994). In the above-mentioned study by Myers et al. (2014), humor was significantly related to students’ affect toward the instructor, state motivation, and their communication satisfaction. That is, instructor humor seems to be relevant for learners’ motivation. On the contrary, motivation was perceived as a student-owned state, and lack of motivation was rated as a teacher-owned problem: Negative teacher behavior (e.g., no sense of humor, loses temper) was perceived as central to college students’ demotivation. And teachers’ positive behavior (e.g., sense of humor) was perceived as central to motivation (Gorham & Christophel, 1992). Additionally, Saroglou and Scariot (2002) reported that students’ negative humor styles (i.e., aggressive and self-defeating) were related to their low school motivation.

Affect and Appraisal Affect and cognitive appraisal are mechanisms that can potentially explain why humor is related to outcomes. Humor seems to attenuate affect. Advisors’ humor was positively related to advisee affect in a graduate context, whereas verbal aggression was negatively related to affect (Wrench & Punyanunt-Carter, 2005). In an early experiment with tape recordings (hostile, non-hostile, non-humorous) by Dworkin and Efran (1967) using a sample of 50 male US students, humor significantly reduced reported feelings of anger and anxiety; and angry participants appreciated hostile humor more than non-angry participants. Experimental research (in advertising) found a beneficial effect of humor for reducing vulnerability to shame, especially for persons with higher fear of negative evaluation (Yoon, 2015).

There is one study showing that humor relates to appraisal. In a study of 81 Canadian students, Kuiper, McKenzie, and Belanger (1995) found that cognitive appraisal for a drawing task was related to sense of humor as measured by the Situational Humor Response Questionnaire (SHRQ), Coping Humor Scale (CHS), and the Sense of Humor Questionnaire (SHQ, metamessage sensitivity/MS, personal liking of humor/LH, but not emotional expressiveness/EE); that is, more humorous people changed their perspective more often for stressful (vs. pleasant) events. Higher humor levels were associated with higher challenge/lower threat appraisals, higher levels of task motivation, and more positive affect.

In sum, humor seems to be related to motivation, affect, and appraisal in learning contexts. However, the nature of the relationships has mostly been examined in correlational studies and the lab experiments are rather outdated. Moreover, studies about humor and learning in the work context with regard to psychological effects are lacking.

6.5 Mode of Presentation

Whether humor effects vary if used for verbal instruction, tests, textbooks, or online instruction is largely unknown. However, there is initial research about humor use in these different modes, though almost exclusively from school and not work contexts.

6.5.1 Humor in Textbooks and Tests

Humor in textbooks Humor in textbooks may be more enjoyable but did little for learning, memory, and interest and was even worse for the credibility of the author (Bryant et al., 1981; Klein, Bryant, & Zillmann, 1982). In 2014, Piaw published a study of effects of humor cartoons in a book about research methods and statistics (five volumes) in Malaysia. The majority of 379 readers (students) assessed the cartoons as making reading and learning fun, enhancing understanding and meaning, but around 5 percent responded negatively as humor reduced formality. In an experiment with 66 Malaysian school assistant principles, the book with cartoons was superior over the book with text-only in reading comprehension and reading motivation. Though humor in textbooks may be used to enhance their appeal, evidence for enhanced learning is still missing.

Humor in Tests Humor in tests is meant to enhance students’ performance, their appreciation, and reduce anxiety.

Besides an experimental study by Berk and Nanda (2006), there is little evidence that students’ actual performance benefits from humorous tests and exams. Berk and Nanda (2006) found that humor in test instructions (but not items) was significantly related to increased test performance of US students on constructed-response problem-solving items (but not on multiple-choice tests).

However, students seem to respond favorably to humorous items in tests (e.g., Deffenbacher, Deitz, & Hazaleus, 1981). McMorris, Boothroyd, and Pietrangelo (1997) recommended the use of appropriate and constructive humor on exams or tests in order to enhance enjoyment for students.

The attenuating effects of the use of humor on trait anxiety (e.g., as stated by Field, 2009) have not been unequivocally supported as some studies have provided support but others have presented contrary findings. That is, highly test-anxious students performed significantly better (Smith, Ascough, Ettinger, & Nelson, 1971) or worse (Deffenbacher et al., 1981) in the humor condition than those in the non-humorous condition. However, Berk and Nanda (2006) did not find humor to be a moderator of anxiety effects, but attributed this finding to the very low levels of pre-anxiety.

6.5.2 Online Instruction

Online humor seems to be beneficial for activation, engagement, and motivation of students, but little is known about learning success. However, students’ perceptions of their skill development do not seem to differ between online and face-to-face courses (Fortune, Shifflett, & Sibley, 2006).

In a study of 43 students in an online class, those in the “humor-enhanced” condition were more active (e.g., posting) as compared with those in the non-humorous condition (Shatz & LoSchiavo, 2006). Likewise, in an experiment with 266 US students over an entire semester course, the students whose instructors’ used humor via a course-based social network had higher engagement in this network (if students spend a high amount of time there) as compared to the control group with non-humorous instructors (Imlawi, Gregg, & Karimi, 2015). Also, students’ network engagement was associated with higher students’ motivation to learn and satisfaction with learning.

On the one hand, online students (Generations X and Y) are tech-savvy and may expect more entertainment in classes. On the other hand, online instructors found that it takes extra planning and effort to make humor happen in online classes (Taylor, Zeng, Bell, & Eskey, 2010). Special caution is indicated as written jokes cannot be revoked, and thus offensive topics (e.g., religion, race, gender, age, or bodily functions) should be avoided (Krovitz, 2007; cf. Taylor et al., 2010). However, the avoidance of offensive topics is an important rule to follow in offline settings, too.

6.6 Humor in Learning/Instruction in Work Contexts

Up to this point, all studies that have been cited were conducted in non-work contexts (irrespective of the fact that schools are teachers’ workplaces). Though several aspects of humor in instruction may easily be transferred to work contexts (e.g., immediacy, attention, and creativity), empirical evidence is needed.

Two cross-sectional self-report studies in the work context of schools related humor to employees’ psychological and cognitive outcomes. Principals’ humor style was associated with teachers’ work motivation (Recepoğlu, Kilinç, & Çepni, 2011), and using humor in the learning content of nursing courses promoted learners’ critical thinking and emotional intelligence, according to qualitative interviews with teachers (Chabeli, 2008). However, both studies had methodological shortcomings and a very limited focus and thus deserve a more sophisticated replication.

A rather distal study related to the work context (though maybe to speeches by top management) was conducted by Greatbatch and Clark (2003): Gurus used verbal and nonverbal humor practices in their lectures to project clear message-completion points, to signal their humorous intent, to “invite” audience laughter, and to manipulate the relations between their use of humor and their core ideas and visions. That said, evidence for the effects of humor in learning and training or effects of humorous trainings in the work context is missing, thus being “unworked fields” in need of future research. Likewise, humor in work-related print products (e.g., brochures, guidelines) may enhance attention, but besides the higher appeal of (information/instructional) material, the beneficial function of humor for retention or even compliance needs to be tested.

6.7 Conclusions

The following statement has yet to find unequivocal support: “Humor appropriately used has the potential to humanize, illustrate, defuse, encourage, reduce anxiety, and keep people thinking” (Torok et al., 2004, p. 14). Also, with regard to Field’s (2009) conclusion that humor can make students love statistics and that it can reduce anxiety but should be topic related, only the topic-related part has been empirically supported.

Though the use of humor for learning and instruction in the work context seems promising, its mechanisms or effects have yet to be measured. The benefits seem to stem from the positive side of humor styles, and the drawbacks from the negative side, including offensive humor. Rather than presenting ultimate knowledge, the findings presented in this chapter serve as the basis for future research in the work context.

6.7.1 Future Research

There is little research on the use of humor in learning/teaching or training, it is dated, and it has not fully explored the influences of different forms of humor, the placement of humor, and how well humor should be aligned with the concepts being taught. Also, the impact of student-initiated joking and related students’ agency on classroom interactions (Davies, 2015) is an interesting field for future research in instruction and training contexts. The propositions on the beneficial functions of humor in instruction have found mixed support in studies that have primarily explored student samples as very few studies have been conducted in the work context. For instance, the role of humor in instructing employees with external or in-house trainers might be a worthwhile area of research. That said, virtually all aspects of the use of humor for training purposes are in urgent need of research applying sophisticated methods, including different sources and the work context. Additionally, methods from other disciplines may be transferred to psychological humor research (e.g., communications analyses, Reddington & Waring, 2015).

Accordingly, the following important research questions in this area are very broad and far from exhaustive:

-

1.

Which previous findings are replicable in learning and training in work contexts?

-

2.

What are the mechanisms for the effects of humor in learning and training in work contexts?

-

3.

What are the boundary conditions for the consequences of humor; that is, under what circumstances are certain forms of humor effective?

6.7.2 Recommendations for Practice

Generally, humor that is judged as always appropriate (e.g., affiliative, self-enhancing) or appropriate depending on the context (e.g., self-disparaging, unplanned humor, jokes) should be preferred over inappropriate types (e.g., aggressive, offensive humor) in the classroom (Banas et al., 2011). Also, sexual themes should be avoided (e.g., Field, 2009). Likewise, ridiculing coworkers or subordinates may serve the short-term goal of enforcing norms or correcting behavior (e.g., Bryant et al., 1983), but has negative long-term effects on climate (see Janes & Olson, 2000, for classrooms).

Based on students’ perception of appropriate humor in the classroom (Weaver & Cotrell, 2001), several techniques for developing appropriate humor for learning and instruction in the work context may be inferred but need to be tested (e.g., smile; use humorous stories; encourage a give-and-take climate). However, in order to avoid excessive humor, the techniques should be chosen adequately and sparsely. Similarly, Torok et al. (2004) adopted Provine’s (2000) recommendations for increasing humor in the classroom, that is, increase interpersonal contact through face-to-face contact, create a casual and safe atmosphere, adopt a laugh-ready attitude, provide humorous materials, and remove social inhibitions. Aside from the removal of social inhibitions, these aspects are well-aligned with work contexts. For instance, humor may enhance the appeal of safety instructions by fostering positive affect and attention. Also, humor may be used to maintain a safe space to communicate across differences by challenging ill-informed or intolerant statements (Rocke, 2015).

-

Recommendations for further reading:

Banas, J. A., Dunbar, N., Rodriguez, D., & Liu, S.-J. (2011). A review of humor in educational settings: Four decades of research. Communication Education, 60(1), 115–144. doi:10.1080/03634523.2010.496867.

Lei, S. A., Cohen, J. L., & Russler, K. M. (2010). Humor on learning in the college classroom: Evaluating benefits and drawbacks from instructors’ perspectives. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 37(4), 326–333.

Martin, R. A. (2007). The psychology of humor: An integrative approach. London: Elsevier Academic Press.

Neuliep, J. W. (1991). An examination of the content of high school teachers’ humor in the classroom and the development of an inductively derived taxonomy of classroom humor. Communication Education, 40, 343–355.

References

Allen, L. (2014). Don’t forget, thursday is test[icle] time! Sex Education, 14(4), 387–399. doi:10.1080/14681811.2014.918539.

Banas, J. A., Dunbar, N., Rodriguez, D., & Liu, S.-J. (2011). A review of humor in educational settings: Four decades of research. Communication Education, 60(1), 115–144. doi:10.1080/03634523.2010.496867.

Belanger, H. G., Kirkpatrick, L. A., & Derks, P. (1998). The effects of humor on verbal and imaginal problem solving. Humor - International Journal of Humor Research, 11(1), 21–31.

Berk, R. A. (1998). Professors are from Mars, students are from Snickers: How to write and deliver humor in the classroom and in professional presentations. Madison, WI: Magna Publications.

Berk, R. A., & Nanda, J. (2006). A randomized trial of humor effects on test anxiety and test performance. Humor—International Journal of Humor Research, 19(4), 425–454. doi:10.1515/HUMOR.2006.021.

Bolkan, S., & Goodboy, A. K. (2015). Exploratory theoretical tests of the instructor humor–student learning link. Communication Education, 64(1), 45–64. doi:10.1080/03634523.2014.978793.

Bressler, E. R., & Balshine, S. (2006). The influence of humor on desirability. Evolution and Human Behavior, 27(1), 29–39. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2005.06.002.

Bryant, J., Brown, D., Parks, S. L., & Zillmann, D. (1983). Children’s imitation of a ridiculed model. Human Communication Research, 10(2), 243–255. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1983.tb00013.x.

Bryant, J., Brown, D., Silberberg, A. R., & Elliott, S. M. (1981). Effects of humorous illustrations in college textbooks. Human Communication Research, 8(1), 43–57.

Bryant, J., Comisky, P. W., Crane, J. S., & Zillmann, D. (1980). Relationship between college teachers’ use of humor in the classroom and students’ evaluations of their teachers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 72(4), 511.

Carlson, K. A. (2011). The impact of humor on memory: Is the humor effect about humor? Humor - International Journal of Humor Research, 24(1). doi:10.1515/humr.2011.002.

Chabeli, M. (2008). Humor: A pedagogical tool to promote learning. Curationis, 31(3), 51–59.

Cheng, D., & Wang, L. (2014). Examining the energizing effects of humor: The influence of humor on persistence behavior. Journal of Business and Psychology. doi:10.1007/s10869-014-9396-z.

Christophel, D. M. (1990). The relationships among teacher immediacy behaviors, student motivation, and learning. Communication Education, 39, 323–340.

Davies, C. E. (2015). Humor in intercultural interaction as both content and process in the classroom. Humor - International Journal of Humor Research, 28(3), 375–395. doi:10.1515/humor-2015-0065.

Deffenbacher, J. L., Deitz, S. R., & Hazaleus, S. L. (1981). Effects of humor and test anxiety on performance, worry, and emotionality in naturally occurring exams. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 5(2), 225–228.

Dworkin, E. S., & Efran, J. S. (1967). The angered: Their susceptibility to varieties of humor. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 6(2), 233–236.

Field, A. (2009). Can humour make students love statistics? Humor and Statistics, 22(3), 210–213.

Filipowicz, A. (2006). From positive affect to creativity: The surprising role of suprise. Creativity Research Journal, 18(2), 141–152.

Fortune, M. F., Shifflett, B., & Sibley, R. E. (2006). A comparison of online (high tech) and traditional (high touch) learning in business communication courses in Silicon Valley. Journal of Education for Business, 81(4), 210–214. doi:10.3200/JOEB.81.4.210-214.

Frymier, A. B. (1994). A model of immediacy in the classroom. Communication Quarterly, 42(2), 133–144.

Frymier, A. B., Wanzer, M. B., & Wojtaszczyk, A. M. (2008). Assessing students’ perceptions of inappropriate and appropriate teacher humor. Communication Education, 57(2), 266–288. doi:10.1080/03634520701687183.

Goodboy, A. K., Booth-Butterfield, M., Bolkan, S., & Griffin, D. J. (2015). The role of instructor humor and students’ educational orientations in student learning, extra effort, participation, and out-of-class communication. Communication Quarterly, 63(1), 44–61. doi:10.1080/01463373.2014.965840.

Gorham, J., & Christophel, D. M. (1992). Students’ perceptions of teacher behaviors as motivating and demotivating factors in college classes. Communication Quarterly, 40(3), 239–252.

Greatbatch, D., & Clark, T. (2003). Displaying group cohesiveness: Humour and laughter in the public lectures of management gurus. Human Relations, 56(12), 1515–1544. doi:10.1177/00187267035612004.

Hampes, W. P. (2010). The relation between humor styles and empathy. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 6(3), 34–45.

Hauck, W. E., & Thomas, J. W. (1972). The relationship of humor to intelligence, creativity, and intentional and incidental learning. The Journal of Experimental Education, 40(4), 52–55.

Imlawi, J., Gregg, D., & Karimi, J. (2015). Student engagement in course-based social networks: The impact of instructor credibility and use of communication. Computers & Education, 88, 84–96. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2015.04.015.

Isen, A. M., Daubman, K. A., & Nowicki, G. P. (1987). Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(6), 1122.

Janes, L. M., & Olson, J. M. (2000). Jeer pressure: The behavioral effects of observing ridicule of others. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(4), 474–485. doi:10.1177/0146167200266006.

Kaplan, R. M., & Pascoe, G. C. (1977). Humorous lectures and humorous examples: Some effects upon comprehension and retention. Journal of Educational Psychology, 69(1), 61.

Klein, D. M., Bryant, J., & Zillmann, D. (1982). Relationship between humor in introductory textbooks and student’s evaluations of the texts’ appeal and effectiveness. Psychological Reports, 50(1), 235–241. doi:10.2466/pr0.1982.50.1.235.

Krovitz, G. (2007, May 9). Using humor in online classes. Educator’s Voice, 8(2), 1–2.

Kuiper, N. A., McKenzie, S. D., & Belanger, K. A. (1995). Cognitive appraisals and individual differences in sense of humor: Motivational and affective implications. Personality and Individual Differences, 19(3), 359–372.

Lei, S. A., Cohen, J. L., & Russler, K. M. (2010). Humor on learning in the college classroom: Evaluating benefits and drawbacks from instructors’ perspectives. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 37(4), 326–333.

Martin, R. A. (2007). The psychology of humor: An integrative approach. London: Elsevier Academic Press.

McMorris, R. F., Boothroyd, R. A., & Pietrangelo, D. J. (1997). Humor in educational testing: A review and discussion. Applied Measurement in Education, 10(3), 269–297. doi:10.1207/s15324818ame1003_5.

Myers, S. A., Goodboy, A. K., & Members of COMM 600. (2014). College student learning, motivation, and satisfaction as a function of effective instructor communication behaviors. Southern Communication Journal, 79(1), 14–26.

Neuliep, J. W. (1991). An examination of the content of high school teachers’ humor in the classroom and the development of an inductively derived taxonomy of classroom humor. Communication Education, 40, 343–355.

Nijstad, B. A., De Dreu, C. K. W., Rietzschel, E. F., & Baas, M. (2010). The dual pathway to creativity model: Creative ideation as a function of flexibility and persistence. European Review of Social Psychology, 21, 34–77. doi:10.1080/10463281003765323.

Piaw, C. Y. (2014). The effects of humor cartoons in a series of bestselling academic books. Humor - International Journal of Humor Research, 27(3), 499–520. doi:10.1515/humor-2014-0069.

Provine, R. (2000). Laughter: A scientific investigation. New York: Viking Adult.

Recepoğlu, E., Kilinç, A. Ç., & Çepni, O. (2011). Examining teachers’ motivation level according to school principals’ humor styles. Educational Research and Reviews, 6(17), 928–934.

Reddington, E., & Waring, H. Z. (2015). Understanding the sequential resources for doing humor in the language classroom. Humor - International Journal of Humor Research, 28(1), 1–23. doi:10.1515/humor-2014-0144.

Rocke, C. (2015). The use of humor to help bridge cultural divides: An exploration of a workplace cultural awareness workshop. Social Work with Groups, 38, 152–169. doi:10.1080/01609513.2014.968944.

Saroglou, V., & Scariot, C. (2002). Humor Styles Questionnaire: Personality and educational correlates in Belgian high school and college students. European Journal of Personality, 16(1), 43–54. doi:10.1002/per.430.

Scheel, T., Bachmann, S., Gerdenitsch, C., & Korunka, C. (2015). The humor-creativity pathway: Experimenting with affect. Poster presentation at the 17th European Congress on Work and Organizational Psychology [EAWOP] (Oslo/Norway, 20.–23.05.2015).

Schmidt, S. R. (1994). Effect of humor on sentence memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 20(4), 953–967.

Schmidt, S. R. (2002). The humour effect: Differential processing and privileged retrieval. Memory, 10(2), 127–138.

Schmidt, S. R., & Williams, A. R. (2001). Memory for humorous cartoons. Memory & Cognition, 29(2), 305–311.

Shatz, M. A., & LoSchiavo, F. M. (2006). Bringing life to online instruction with humor. Radical Pedagogy, 8(2). Retrieved from http://www.radicalpedagogy.org/radicalpedagogy/Bringing_Life_to_Online_Instruction_with_Humor.html.

Smith, R. E., Ascough, J. C., Ettinger, R. F., & Nelson, D. A. (1971). Humor, anxiety, and task performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 19(2), 243–246.

Stuart, W. D., & Rosenfeld, L. B. (1994). Student perception of teacher humor and classroom climate. Communication Research Reports, 11(1), 87–97.

Suzuki, H., & Heath, L. (2014). Impacts of humor and relevance on the remembering of lecture details. Humor—International Journal of Humor Research, 27(1), 87–101. doi:10.1515/humor-2013-0051.

Taylor, C., Zeng, H., Bell, S., & Eskey, M. (2010). Examining the do’s and don’ts of using humor in the online classroom. In TCC Worldwide Online Conference (Vol. 2010, pp. 31–46). Retrieved from http://www.editlib.org/p/43757/.

Torok, S. E., McMorris, R. F., & Lin, W.-C. (2004). Is humor an appreciated teaching tool? College Teaching, 52(1), 14–20.

Wanzer, M. B., & Frymier, A. B. (1999). The relationship between student perceptions of instructor humor and students’ reports of learning. Communication Education, 48, 48–62.

Wanzer, M. B., Frymier, A. B., & Irwin, J. (2010). An explanation of the relationship between instructor humor and student learning: Instructional humor processing theory. Communication Education, 59(1), 1–18. doi:10.1080/03634520903367238.

Wanzer, M. B., Frymier, A. B., Wojtaszczyk, A. M., & Smith, T. (2006). Appropriate and inappropriate uses of humor by teachers. Communication Education, 55(2), 178–196. doi:10.1080/03634520600566132.

Weaver, R. L., & Cotrell, H. W. (2001). Ten specific techniques for developing humor in the classroom. Education, 108(2), 167–179.

Wrench, J. S., & Punyanunt-Carter, N. M. (2005). Advisor–advisee communication two: The influence of verbal aggression and humor assessment on advisee perceptions of advisor credibility and affective learning. Communication Research Reports, 22(4), 303–313. doi:10.1080/000368105000317599.

Yoon, H. (2015). Humor effects in shame-inducing health issue advertising: The moderating effects of fear of negative evaluation. Journal of Advertising, 44(2), 126–139.

Zillmann, D., Williams, B. R., Bryant, J., Boynton, K. R., & Wolf, M. A. (1980). Acquisition of information from educational television programs as a function of differently paced humorous inserts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 72(2), 170–180.

Ziv, A. (1976). Faciliating effects of humor on creativity. Journal of Educational Psychology, 68(3), 318–322.

Ziv, A. (1988). Teaching and learning with humor: Experiment and replication. Journal of Experimental Education, 57(1), 5–11.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Scheel, T. (2017). Humor and Learning in the Workplace. In: Humor at Work in Teams, Leadership, Negotiations, Learning and Health. SpringerBriefs in Psychology. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65691-5_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65691-5_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-65689-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-65691-5

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)