Abstract

Rohit K. Dasgupta builds on the complexity of negotiating identity in public spaces by refocusing attention on the subversive potential of digital queer spaces in India. Academic discourses on queer sexuality in contemporary India have so far concentrated on textual, cinematic, and sociological representations, with little scholarship on the digital landscape and the various ways in which it shapes the construct of the queer male identity in India. Dasgupta examines how Internet and digital technologies, the media industry, and sociohistorical contexts provide a subversive space within which queer male identity is negotiated. Also offering an overview of media development in India, Dasgupta discusses queer representations in mass media and digital queer spaces in India, which are a consequence of the shifting political and social landscapes of urban and suburban India. Finally, Dasgupta reviews key debates in digital culture and queer studies, situating the Indian queer digital space within the intersection of globalization and postcolonial praxis.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

In June 2008, queer organizations in three major Indian cities—New Delhi, Mumbai, and Chennai—held simultaneous Gay Pride protest marches, with a total turnout of approximately 1000 persons, a very significant number at that time. While queer groups in Kolkata have sporadically organized such annual marches since 1999, this was the first time that it occurred on a national scale protesting against Section 377 of the Indian penal code . Instituted in 1860, Section 377 was driven by a Victorian purity campaign to regulate sexuality in the colonies. The law reads:

Whoever voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal, shall be punished with imprisonment for life, or with imprisonment of either description for a term, which may extend to ten years, and shall be liable to fine.

Explanation: Penetration is sufficient to constitute the carnal intercourse necessary to the offence described in this section. (Narrain and Eldridge 9)

On July 2, 2009, the Delhi High Court ruled that Section 377 of the Indian penal code which criminalized “carnal intercourse against the order of nature” violated the country’s constitution guaranteeing dignity, equality, and freedom to its citizens (Narrain and Eldridge 9). The judges read down (limiting the meaning of the words in the legislation) Section 377, decriminalizing consensual sex between adults of the same sex in private. This landmark judgment overturned a 150-year-old law that for years had denied queer citizens the right to be open about their sexuality.

Scholars have argued how queer identities dismantle the “purity” of an Indian nationhood by disorienting the idea of commonality which ties all citizens together within this mythic national citizenship (Bose and Bhattacharya x). As Judith Butler and Gayatri Spivak note, “If the state is what binds, it is also clearly what can and does unbind. And if the state binds in the name of the nation, conjuring a certain version of the nation forcibly, if not powerfully, then it also unbinds, releases, expels, banishes” (4–5). It is therefore important to complicate and understand queerness in India through the prism of the state and the idea of belonging.

I begin this chapter by examining India’s media history. India’s media history runs parallel to its social history and plays a significant role in understanding and interpreting India’s changing social landscape. I trace this to the post-liberalized phase of India’s media history which started in 1991. I also explain the role of mass media in the development of a universal Indian subject which itself was authored and created along colonial subjectivity. It is imperative to critique this notion of a universal nationalism which is based on a presumptive commonality. As I argue elsewhere (Dasgupta and Gokulsing 6), the history of queer sexuality in India is complicated, and modern homophobia is a remnant of the complex postcolonial modernity of the country. Thus, negotiating Indian-ness with queer-ness becomes a complex discourse on politics of nationalism. India’s global power stems from its digital development; therefore, this chapter goes on to acknowledge the development of this new media and finally examining how the queer male community in India have used these online opportunities to test their identities, connect and construct communities, and mobilize political change through a critique of nationalism and the hegemony of national identities. This chapter addresses the politics of queer male sexualities in contemporary India by exploring its manifestation in digital spaces. I shall demonstrate how such spaces have been used by the queer male community to test their identities, connect and construct communities, and mobilize political change through a critique of nationalism and the hegemony of national identities.

Media Liberalization and Queer Media, 1991–2012

Colonialism and nationalism have a very intrinsic relationship with mass media. During British colonialism, the establishment of media institutions like the All India Radio were specifically created to carry out the propaganda of the British government against the Indian National Congress and the axis powers (Athique 25). With the end of colonial rule, the anti-colonial movement set about to create their version of a “nation state” with the backing of a state-owned media.

The development of modern media was in direct contravention to Gandhi’s ideals of austerity and simplicity. His ideal of a traditional preindustrial society as a model for modern India did not reconcile with the urban medium of media (in this case, cinema). However, Nehruvian politics differed vastly from Gandhi’s ideals and was in favor of advancing India’s scientific and technological objectives (Athique 18–21). India’s national rhetoric which was based on tradition and the rewriting of a precolonial past was underpinned by historicist notions which ranged against neocolonial advent of modernity which Western media and technology represented. The legitimacy of media was only included within the political discourse in 1959, when television made its appearance in India through a gift from Philips supplemented by a UNESCO grant. This led to the establishment of “tele-clubs” in middle- and lower-middle-class localities of Delhi followed by a roll-out rural program. The first regular daily service was started in 1965, and by 1967, the most popular daily service was Krishi Darshan, a program on agricultural development (Gokulsing 8). K. Moti Gokulsing argues that whilst media development in India was intended to provide a platform for dialogue between the government and the people, by the 1970s, it became the political voice of the government, which they used less for dialogue and more for “talking to” the people in India (14–15). Adrian Athique points out that a liberalization period in Indian media started in 1991, which marked the transition “from an era of statist monopoly … to an era of popular entertainment, cosmopolitan internationalism” (69). This then became a time for “individualism and for the expression of a list of desires that were long suppressed in the name of national integration” (Athique 69).

The first phase of this liberalization was the deregulation of Indian television which followed the rapid growth of private entertainment-based television stations against the state-owned Doordarshan in 1991 followed by the growth of regional television and print media. But as Gokulsing and Wimal Dissanayake remind us the presence of regulatory bodies under the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, of the Government of India, still have the power to rate and review audio visual materials meant for public consumption (159). This is exercised very stringently by the Central Board of Film Classification (CBFC) which was constituted by the Cinematograph Act of 1952 and the Cinematograph Certification Rules, 1983, for Indian films (Gokulsing and Dissanayake 160). The guidelines governing this body is so wide that the “State can, if it desires, restrain any film from public viewing on grounds of security or morality or some other issue” (160). The CBFC has a strong record of denying certification to films with queer storylines. Gokulsing and Dissanayake as a case in point refer to Sridhar Rangayan’s 2003 film, Gulabi Aina (The Pink Mirror) which is about transsexuals. The film was denied certification on the grounds that it had vulgar and offensive content. The filmmaker appealed twice but failed to obtain a censor certificate without which films cannot be distributed or screened for commercial purposes. However, in the last five years, a few films with queer storylines and queer characters (Dunno Y Na Jane Kyun, My Brother Nikhil, I Am) have received censor certification and been screened for adult audiences.

Queer media in India can be found in various mediums and in various languages. In this section, I have chosen to look at both the print and visual medium. I recognize trying to document the entire media coverage related to queer issues since 1991 would be too vast for the purposes of this chapter and thesis, I have therefore chosen to provide some representative examples from three areas—the English language print media, Indian cinema, and television. These in turn will lead to an entry point to look at digital queer spaces .

Mainstream press coverage related to queer-related issues in India can be traced back to the early 1990s. Parmesh Shahani provides a few interesting examples of the tone these articles take. He argues “some of these articles were positive and almost evangelical in their tone,” on the other hand, there were also articles which were “uninformed, replete with negative stereotypes about homosexuality and gay men; and downright silly” (175). Sandip Roy notes that the English language media in India started as a “Gay 101 story” which featured an interview with a psychiatrist, quotes from queer people with changed names, and finally an activist intervention. However, publications such as Times of India (Gupta), The Telegraph (Basu), and Society (Roy and Sen) have in recent years published several opinion pieces arguing for acceptance of queer people within the Indian society. The Society piece, for example, interviews parents of LGBT children and their concerns about their children’s sexuality. Many have written about their struggle with society and acceptance of their children. Of course, not all coverage has been positive. There is also an element of sensationalism which drives coverage of queer-related issues. Examples of this include the 2006 media coverage of police-aided harassment of the queer community in Lucknow, when the papers offered variations on what the Hindustan Times reported as “Cops Bust Gay Racket.” The sensational coverage revealed names and addresses of all those who were involved in the “racket” which included “chatting with gay members at an Internet site” and “meet for physical intimacy.” However, running parallel to this form of homophobic media was also the establishment of queer publications such as Bombay Dost by Ashok Row Kavi, in 1990, which ushered queer revolution in queer media, followed quickly by other magazines and ezines such as Gaylaxy, Pink Pages India, and gaysifamily, to name a few.Footnote 1

Indian television has also played a huge role in the public perception of queer people in India. Chat shows such as Kuch Dil Se (From the Heart), telecast in 2004, Zindagi Live (Life), and We the People in the last two years have time and again invited queer-identified people on their panels as guests and have been sympathetic toward queer-related issues. In fact, Barkha Dutt, host of We the People, proudly declares that it was one of first television shows that has tirelessly advocated for the decriminalization of homosexuality in India.Footnote 2 Reality television shows such as Big Boss (Season 1, 2006) which featured the openly gay actor Bobby Darling further tried to push queer consciousness within the domestic space of India; however, his departure within the first week is a testimony to the passive homophobia of both contestants and viewers who decided to vote him off over the other participants. A recent Hindi soap, Maryada: Lekin Kab Tak (Honour: But for How Long? 2010) is credited for being the first national prime time soap to feature a gay storyline. This was a watershed moment as previous soaps such as Jassi Jaisi Koi Nahin (No One Like Jassi, 2003, an Indian version of Ugly Betty) and Pyaar Ki Ek Kahaani (This Is a Story About Love, 2010) featured queer characters as a stereotype to provide humor or a subplot to the main story. Similar changes can also be noticed within regional television; Kaushik Ganguly’s Bengali television film Ushnatar Jonnyo (For Her Warmth, 2002), a homoerotic story about two female friends, signals this magnitude of transformation that Indian television has been witnessing in the last decade. However, incidents such as the sting attack carried out by the Hyderabad television channel TV9 last year exposing gay men on social networking sites have drawn widespread criticism from both queer activists and mainstream media.

It is, however, the film medium in India which has been the most significant influence in establishing the public consciousness about queer identities and issues. Deepa Mehta’s film Fire (1996), which drew the ire of the Hindu right wing for portraying a lesbian love story, also opened up lively debates around female sexuality and queer identities in India. Naisargi Dave argues how a new social world of lesbian activists emerged in India around the text of a sign reading “Indian and Lesbian” which was used during the counter protest demonstrations for the film (1). Gokulsing and Dissanayake writing about Indian popular cinema argue that “the discourse of Indian Popular Cinema has been evolving steadily over a century in response to newer social developments and historical conjunctures” (17). Cinema in India participates in the continual reconstruction of the social imaginary. In addition to being a “dominant form of entertainment,” Indian cinema also represents the interplay of the global and local (Gokulsing and Dissanayake 15). While popular Indian cinema has a long history of featuring cross-dressing male stars in comic or song sequences, films in the 1990s and the 2000s, such as Mast Kalandar (Intoxicated, 1991), Raja Hindustani (Indian King, 1996), Dulhan Hum Le Jayenge (We Will Take the Bride, 2000), Mumbai Matinee (2003), Rules Pyar Ka Superhit Formula (Rules: The Superhit Formula for Love, 2003), and Page Three (2004), saw a shift from the stereotypical effeminate gay characters in the earlier films to more complicated layered gay characters in the later ones. This was followed by Onir’s path-breaking film My Brother Nikhil (2005), which for the first time featured a HIV-positive gay character in the main role. In addition, two other films, Kal Ho Na Ho (If Tomorrow Never Comes, 2003) and Dostana (Friendship, 2008), using the trope of “mistaken identity” and “misreading,” represents and stages homoerotic play and queer performativity . Rajinder Kumar Dudrah questions whether these films simply offer cheap thrills and comedy, or if they engage meaningfully with queer representations and possibilities. Recognizing the “secret politics of gender and [queer] sexuality in Bollywood,” Dudrah writes that “These codes and their associated politics are attempted to be spoken, seen and heard cinematically that little bit more loudly; not yet as radical and instant queer political transformation, but as implicit and suggestive queer possibilities that are waiting to be developed further” (45, 61). In addition to these and numerous other mainstream Bollywood films, there are also significant queer films being made in regional film industries such as Bengali, including Memories in March (2010), Arekti Premer Golpo (Not Another Love Story, 2010), and Chitrangada (2012), to name a few. There is also a very strong non-commercial film sector in India spearheaded by queer filmmakers such as the late Riyad Wadia, Nishit Saran, Sridhar Rangayan,Footnote 3 and others. The establishment of several queer film festivals across India are a testimony to the growing number of such films being made each year.

On Online Queer Spaces

As the above sections demonstrate, media representations of queer people in India have not had a linear development; it has changed over time due to societal and political change. While some sections of the media have been sympathetic to queer people, other sections of the media, fueled by jingoistic nationalism, have castigated and portrayed queer people in a very negative light. These have been major factors and a driving force behind the emergence of an alternative social space offered by the Internet. Identities as we are aware are contextualized within the various scapes (Appadurai 5) within which we inhabit. These range from home, nation, and community to gender and sexual preferences. My discussions in this section will turn and overturn these space terrains. Benedict Anderson in his famous narrative analysis of nationhood, Imagined Communities contends that a nation exists because people believe in them. Membership to this community is governed through a collective common origin, characteristics, and interests. The space of home, community, and nation has at its foundation a shared commonality. Stuart Hall contends that there are “people who belong to more than one world, speak more than one language and inhabit more than one identity, have more than one home” (206). Hall’s insightful writing dislocates the notion of homogeneity, replacing it with heterogeneous identities in a new global world. Thus, the idea of home is in constant flux. The idea of home becomes more problematic when dissonant identities, in this case queer identities, conflict with the heterogeneity of a national identity.

The emergence of the Internet has had a profound impact on human life. By destabilizing the boundaries between the private and public, new spaces have opened for social interaction and community formation. Thomas Swiss and Andrew Hermann examine the Internet as a unique cultural technology, where several complex processes come together: “The technology of the World Wide Web, perhaps the cultural technology of our time, is invested with plenty of utopian and dystopian mythic narratives, from those that project a future of a revitalized, Web based public sphere and civil society to those that imagine the catastrophic implosion of the social into the simulated virtuality of the Web” (2). The idea of a utopian world being created through the Internet envisages cyberspace as a safe and accommodating sphere, where communities can interact and grow. The concept of an online community was first advocated by Howard Rheingold in 1993 when he coined the term “Virtual Community.” Taking on Anderson’s idea of an “imagined community,” Rheingold writes, “virtual communities require an act of imagination to use … and what must be imagined is the idea of the community itself” (54). Radhika Gajjala and Rahul Mitra suggest that cyberspace is not a place, it is a locus around which modes of social interaction, commercial interests, and other discursive and imaginative practices coalesce. The emergence of the Internet in the context of community has resulted in several scholars arguing about the differences between real life and the virtual world. However, writers like Shahani see them as integral to one another: “I do not find this virtual versus real debate useful or productive. People do not build silos around their online and offline experiences—these seep into each other seamlessly” (64). Concurring with Sharif Mowlabocus , who also sees “the gay male subculture as being something that is both physical and virtual” (2), I suggest queer male digital culture in India be seen within the larger context of the social history of the country. The need for safe space is probably the single most important factor that underlies the formation of digital queer spaces . The engagement of queer people using the Internet and other digital spaces reveal one of the many forms of “expression of the personal self within the public sphere” (Pullen 1).

In his study of the relationship between sexual identity and space, Randal Woodland shows how spaces shape identity, and identities shape space. He writes that “the kinds of queer spaces that have evolved to present queer discourse can be taken as measure of what queer identity is in the 1990s” (Woodland 427). In his study of four distinct queer cyberspaces which include private bulletin boards, mainstream web spaces, bulletin board systems (BBS), and a text-based virtual reality system, shows that all these spaces deploy a specific cartography to structure their queer content. However, “one factor that links these spaces with their historical and real life counterparts is the need to provide safe(r) spaces for queer folk to gather” (Woodland 427). The need for safe space is probably the single most important factor that underlies the formation of digital queer spaces , and this will lead toward understanding the queer cyberculture better. Mowlabocus points out that this relationship between the online world created by new media technologies and the offline world of an existing gay male sub-culture complicates the questions concerning the character of online communities and identities. He argues that “the digital is not separate from other spheres of gay life, but in fact grows out of while remaining rooted in, local, national and international gay male subculture” (Mowlabocus 7).

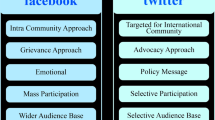

Mowlabocus’s statement about the digital being rooted in the local gay male sub-culture is important in understanding queer cyberspace. I shall argue that while anti-discrimination laws exist on a national level in the UK, some countries in Europe, and parts of the USA, sodomy laws still exist in most parts of the world, and until as recently as 2009, homosexuality was criminalized in India.Footnote 4 It is within this hostile space that I situate queer men using the Internet. Mowlabocus’s study of Gaydar , a popular British gay cruising site, also points to the similarity of multiple queer digital spaces. He goes on to say that “Many of these websites may in fact be peddling the same types of bodies and the same ideological messages as each other” (Mowlabocus 84). However, queer space does not exist solely on queer-identified sites (e.g., Gaydar , Guys4Men , and PlanetRomeo —PR); rather, queer individuals’ encountering one another via mainstream websites, such as Facebook , MySpace, Twitter , and Orkut, have added another dimension to discussions on queer identity and its representations on the Internet.

The Foucauldian idea of space and its subversive potential can be harnessed in the context of the queer cyberspace, which can be read as a Foucauldian heterotopia—a place of difference. Michel Foucault describes it as “something like counter-sites, a kind of effectively enacted utopia, in which the real sites, all the other real sites that can be found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested and inverted” (24). The alternative queer cyberspace can be considered heterotopic, where the utopic place is not only reflected but reconfigured and revealed. Affrica Taylor writes that the “other” spaces of the gays and lesbians destabilize their own territories and meaning just as much as they destabilize the territories of heterosexuality.

At this point, I would like to examine the issue of identity within a postcolonial digital space. The postcolonial approach suggests that subjects position themselves within the narratives of the past and see themselves in relation to it. Treading a similar trajectory, online queer identities are articulated as a position against the hegemony of a singular imagined past. While the queer identity is a point of entry into mainstream politics around restriction and discrimination, it also makes distinctions between identities shaped by culture and geography (the West and the East), social conditions (class structures), and personal identities—ones that we construct on our own. The important point being that identity is constantly reshaping. Jeffrey Weeks calls identities “necessary fictions” that need to be created “especially in the gay world” (98). If we concur with Weeks, then identity can be seen as sites of multiplicity, where identities are performed and contested and constantly reshaped. Identity is at the core of digital queer studies , as Nina Wakeford, in her landmark essay “Cyberqueer ” (1997), also notes, “The construction of identity is the key thematic which unites almost all cyberqueer studies . The importance of a new space is viewed not as an end in itself, but rather as a contextual feature for the creation of new versions of the self” (31). While I recognize that our social and cultural lives are determined by a universal heteronormative code that validates heterosexual signifiers, the cyberqueer identity recognizes multiple sites (in cyberspace) and discourses that give rise to alternative readings of identity and allows one to read the multiplicities and complexities within individual profiles.

Mowlabocus asserts that “If gay male digital culture remediates the body and does so through a pornographic lens, then it also provides the means for watching that body, in multiple ways and with multiple consequences” (81). The Internet does not just allow the browser to be a passive participant but an active one. The participation can be in variety of ways. There are websites which feature coming out stories, which invite the reader to add their own. There are websites such as PR , Guys4Men , and Gaydar which are cruising/dating sites, and finally there are websites which have a more political and health-related output. The subject of online identity is a complex and shifting one. Like every other element of cyberculture, identity is centrally bound to the use of language, from the choice of a name to the representation of the physical self.

What we see here are certain unsettling gestures. Working from a marginalized position and beyond the bounds of that marginality, cyberspace challenges the existing boundaries with which identity is contained, yet presuppositions such as the individual wanting to be “the center of the social universe” are also harnessed. In this sense, while it acts as an erasure of differences by putting all the profiles (and by extension the identities) on the same plane, it also rearticulates the difference and otherness. Virtual communities offer the opportunity for identity testing, preparation for coming out, if one chooses to do so, and a support system throughout the entire process. The Internet thus provides the queer youth with tools to create and refine their queer identities from dating and sexual bonding to politics and activism.

The Internet is entering a phase remarkably linked to the concept of identification. With the proliferation of sites such as Facebook and Twitter , the garb of anonymity which dominated the Internet in the first decade is slowly lifting, when users were translated as stock information which was hidden by a username and information that is endorsed through their registration.

In the discourse of the cyberqueer community, the virtual space, community, identity, and voice of the individuals are all inextricably linked. Woodland points out that “community is the key link between spatial metaphors and issues of identity. By helping to determine appropriate tone and content … community identity also informs the voice and ethos appropriate to members of that community” (Woodland 430).

While early work by scholars see the utopic possibilities of the Internet offering new spaces for political and ideological formations through debates about power, identity, and autonomy and heralding the beginning of a new democracy which is not impinged by race, color, and socioeconomic status, later scholars, such as Tsang, dismiss such utopic declarations. He writes, “Given the mainstream definition of beauty in this society, Asians, gay or straight are constantly reminded that we cannot hope to meet such standards” (Tsang 436). As an example, he states the case of a college student from Taiwan who after changing his ethnicity to white “received many more queries and invitations to chat” (435). Gajjala, Natalia Rybas, and Melissa Altman, writing about race and online identities, critically note, “Race, gender, sexuality, and other indicators of difference are made up of ongoing processes of meaning-making, performance, and enactment. For instance, racialization in a technologically mediated global context is nuanced by how class, gender, geography, caste, colonization, and globalization intersect” (1111). The primary reason for setting up virtual queer communities might have been to create a “safe” space, where people could freely express their identity, “over time such spaces also became sites where identities are shaped, tested, and transformed” (Woodland 430).

Queering the Cyberspace in India

Following the discussions above, it is not surprising that the queer community in India has turned to the Internet and other digital forms of communication to “create a sense of community and solidarity” that are “unbounded by geography.” Gayatri Gopinath articulates how sexual minorities of Indian origin, citing the case of South Asian Lesbian and Gay Association (SALGA), were denied representation at the Annual India Day parade in New York City in 1995 claiming that the group represented “anti-nationalist” sentiments (5). Thus, it would be safe to assume that the brand of Indian nationalism currently espoused by the State of India systematically denies and has been denying queer citizens representation and voice. Arvind Narrain and Gautam Bhan, in their landmark anthology Because I Have a Voice, point out: “It is not just Section 377 that affects queer people—laws against obscenity, pornography, public nuisance and trafficking are also invoked in the policing of sexuality by the state and police. One also has to pay heed to the civil law regime where queer people are deprived of basic rights such as the right to marry or nominate one’s partner” (8–9). In this section, I turn to the creation of online queer spaces in India (and the diaspora) which engage with a new form of queer geography. These spaces act both as a point of resistance to the hegemony of patriarchal heterosexual Indian values and at the same time as a response to “the desire for community” (Alexander 102).

The early 1990s marked the beginning of the information age characterized by economic liberalization and computer technologies. Manuel Castells, one of the leading theorists of globalization marks this as a new social order driven by the rise of informational technology and political processes.Footnote 5 This new form of networked society is driven by the exchange of knowledge. Given the ambitious aim of Nehruvian politics of advancing India’s technological and scientific objectives, it is not surprising that India’s postcolonial elite made their way to Silicon Valley and other “nodes” of information and technological revolution. However, before being accused of creating an elitist and utopic digital world for India, I should clarify that India has also remained a country of deep divides and contrast. The growth of Internet usage in India has been in depth and not in spread. This is to be expected in a highly stratified society like India, the penetration of Internet among urban Indians being around 9 percent and among all Indians about 2 percent. Athique gives three reasons for the low penetration of the Internet in India, that is, the slow growth of computer ownership, capacity shortage in telecommunications, and lastly the content of the Internet being delivered in English (103). However, there has been a huge surge of mobile phones in developing countries around the world, especially in places like India, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh. For 2013–2014, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) reported an overall mobile density of 75.23 percent of the total Indian population (4). These figures are very encouraging, though poor network connectivity and 3G intake means that it will be some time until Internet access is available to most mobile phone users.

South Asian presence has not been very visible on the Internet in the last two decades. The Internet remains a domain of privilege to which most South Asians have little access. Linda Leung, in her research on online geographies of Asia, remarks that “one of the main limitations of the study of Asian online identity and activity is that it has been confined to a narrow socioeconomic demographic” (7). While the Internet is not as white as it once was, it remains restricted to those who have the socioeconomic means to access it. Leung further points out that “Access to cyberspace requires the use, if not the ownership, of a computer, a modem, a telephone service and an Internet provider. These resources are surely not equally distributed amongst the diverse groups of lesbians, gay men, transgendered and queer folk” (Leung 22).

It is, therefore, not surprising that those who have been part of the South Asian diaspora, and more specifically the Indian diaspora, were among the first to inhabit cyberspace, because of their economic standing, in contrast to their counterparts back home. Radhika Gajjala and Venkataramana Gajjala argue that some of the earliest roles played by the Internet for the Indian diaspora were in relation to the establishment of call centers, the proliferation of Bollywood and Indian cinema, and finally helping to arrange marriages.

The Internet began in India in 1995, while online queer presence of South Asians can be traced back to the establishment of the Khush List Footnote 6 which was founded in 1992, and which is one of the “oldest and most established discussion spaces for LGBT-identified South Asians” (Shahani 85). With the establishment of the Khush List , other similar lists, such as SAGrrls and desidykes (a women-only group), emerged in quick succession. Roy, editor and, later, Trikone Magazine board member, writes that Trikone was the first ever queer South Asian website hosted online, in 1995.Footnote 7 One respondent explains:

I am glad the internet is there, without it I would have been lost. My entire self-discovery (of being gay) has been possible because of the internet and sites likes Planetromeo . At home my brother is very homophobic, he always makes very bad remarks about homos. I am always scared to talk to anyone there and don’t feel safe. The same for school, but having Planetromeo has opened up the world for me. I can sit in my chair and talk to other gay boys all the time and they understand me more.

The emergence of the Internet in the context of community has resulted in several scholars arguing about the differences between real life and the virtual world. However, writers such as Shahani see them as integral to one other: “I do not find this virtual versus real debate useful or productive. People do not build silos around their online and offline experiences—these seep into each other seamlessly” (64).

The need for safe space is probably the single most important factor that underlies the formation of digital queer spaces . As my respondents have demonstrated, their public lives be it within the confines of home or school and work are in constant conflict with their queer identities, and it is within the space of PR that they try to create and recreate spaces of relative safety, identity formation, and belonging. These are men who are not only marginalized because of the oppressive impact of homophobia but whose opportunities for self and community formation are constrained because of the lack of social acceptance.

Online sites such as PR represents a space where personal opinions with political overtones and consequences are articulated and shared—a space that is outside the purview of the state. Gajjala and Mitra argue that the connection between voice and space becomes particularly critical when such a space is denied in the real life through marginalizing forces, and a new space needs to be carved out. Spaces such as PR constructs a new Indian public sphere suggesting media activism and alternatives to state responses by gathering together non-recognized actors and giving them a voice. At the same time, it also allows a variety of queer desires to be recognized and acted upon. As one of my respondents, Jasjit, puts it:

I am not an activist. I don’t use Planetromeo to andolanbaazi [for activism]. I’m more interested in having sex and that is primarily what I use it for. It takes care of having to speculate who is gay or not and then the whole dating process. This is faster and instantaneous. In a click I have everything I need to know about him—his likes, dislikes, if he likes to party, his body stats as well as sexual fetishes.

Roy states that the Internet was invaluable for those growing up in small towns that did not have an active queer community. The anonymity offered by the Internet, and the possibility of meeting people from other parts of India and even the world, provided impetus for those queer men using the Internet in these small towns. Gajjala and Mitra writing about Indian queer men living in the rural and small towns of India critically point out that “Even gay men in the smallest, least industrialised, most rural towns of Indian heartland scout for tricks online…. Email and guys4men.com is a great way to make their presence felt in their tiny district (and even though they probably never imagined) in cyberspace” (416). From this homogenizing perspective, cyberspace can be seen as a force that erases the difference of queerness by setting up a dialectic between Indian and queerness , and challenging the assumption of anti-queer nationalism. The cyberspace thus not only allows for alternative communities to form and social interactions to take place but also offers discussion boards for political and social changes relevant to the queer community. While online new media might seem to offer a democratic scope for queer men to engage with issues around subjectivity and identity, we must also remember that this is fragmented and disconnected. The online space cannot just be viewed as an emancipator or all encompassing; rather, issues such as class, gender, and the socioeconomic background of the users play a vital role in the voices that are heard and those that are not. The birth of the cyberqueer in India has opened a vital space for dialogue, activism, and self-exploration .

Notes

- 1.

These are available at http://www.gaylaxymag.com, http://www.pink-pages.co.in, and http://www.gaysifamily.com, respectively.

- 2.

See http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x5_1aXfyw74&feature=share&list=SPE77B5BBB6220A28F, November 4, 2012.

- 3.

Bomgay (1993), A Mermaid Called Aida (1996), Summer in My Veins (1999), Pink Mirror (2006), Yours Emotionally (2007), 68 Pages (2007), and others.

- 4.

In South Asia, homosexuality is currently illegal in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. It was legalized in Nepal in 2007 and India in 2009 (pending Supreme Court decision). Seven countries—Iran, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Nigeria, Mauritania, Sudan, and Yemen—punish homosexuality with the death penalty.

- 5.

See, for example, Networks of Outrage and Hope (2012).

- 6.

Khush List is a bulletin board (http://dir.groups.yahoo.com/group/khush-list). At the time of writing this chapter, the last activity/message posted on the Khush List was February 9, 2012.

- 7.

Trikone and Trikone Magazine (started in 1986) are based in San Francisco. Trikone is one of the earliest South Asian LGBT support groups.

Works Cited

Alexander, Jonathan. 2002. Homo Pages and Queer Sites: Studying the Construction and Representation of Queer Identities on the World Wide Web. International Journal of Sexuality and Gender Studies 7 (2): 85–106. Print.

Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso. Print.

Appadurai, Arjun. 1996. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalisation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Print.

Athique, Adrian. 2012. Indian Media. London: Polity. Print.

Basu, Arundhati. 2008. Breaking Free: Indian Gays Are Getting Organised and Boldly Coming Out. The Telegraph, August 31, 2008. Web. 4 Nov 2012.

Bose, Brinda, and Subhabrata Bhattacharya. 2007. The Phobic and the Erotic: The Politics of Sexualities in Contemporary India. Kolkata: Seagull. Print.

Butler, Judith, and Gayatri Spivak. 2010. Who Sings the Nation State? Kolkata/London: Seagull. Print.

Castells, Manuel. 2012. Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age. Cambridge/Malden: Polity Press. Print.

Cops Bust Gay Racket, Nab SAT Official, 3 Others. 2006. Hindustan Times, January 5, 2006. Web. 4 Nov 2012.

Dasgupta, Rohit K., and K. Moti Gokulsing. 2014. Masculinity and Its Challenges in India: Essays on Changing Perceptions. Jefferson: McFarland. Print.

Dave, Naisargi. 2011. Abundance and Loss: Queer Intimacies in South Asia. Feminist Studies 37 (1): 1–15. Print.

Dudrah, Rajinder Kumar. 2012. Bollywood Travels: Culture, Diaspora and Border Crossings in Popular Hindi Cinema. London: Routledge. Print.

Foucault, Michel. 1986. Of Other Spaces. Diacritics 16: 22–27. Print.

Gajjala, Radhika, and Venkataramana Gajjala, eds. 2008. South Asian Technospaces. New York: Lang. Print.

Gajjala, Radhika, and Venkatrama Gajjala. Introduction. In South Asian Technospaces, ed. R. Gajjala and V. Gajjala, 7–24. New York: Peter Lang. Print.

Gajjala, Radhika, and Rahul Mitra. 2008. Queer Blogging in Indian Digital Diasporas: A Dialogic Encounter. Journal of Communication Inquiry 32 (4): 400–423. Print.

Gajjala, Radhika, Rahul Mitra, Natalia Rybas, and Melissa Altman. 2008. Racing and Queering the Interface: Producing Global/Local Cyberselves. Qualitative Inquiry 14 (7): 1110–1133. Print.

Gokulsing, K. Moti. 2004. Soft-Soaping India: The World of Indian Televised Soap Operas. Staffordshire: Trentham. Print.

Gokulsing, K. 2012. Moti and Wimal Dissanayake. From Aan to Lagaan and Beyond: A Guide to the Study of Indian Cinema. Staffordshire: Trentham. Print.

Gopinath, Gayatri. 2005. Impossible Desires: Queer Diasporas and South Asian Public Cultures. Durham: Duke University Press. Print.

Gupta, Poonam. 2011. Do Desi Parents Accept Their Gay Children? Times of India, July 11, 2011. Web. 4 Nov 2012.

Hall, Stuart. 1995. New Cultures for Old. In A Place in the World? Places, Cultures and Globalization, ed. Doreen B. Massey and Pat Jess, 75–213. New York: Oxford University Press. Print.

Leung, Linda. From ‘Victims of the Digital Divide’ to ‘Techno-Elites’: Gender, Class and Contested ‘Asianness’ in Online and Offline Geographies. In South Asian Technospaces, ed. R. Gajjala and V. Gajjala, 7–24. New York: Peter Lang. Print.

Medhurst, Andy, and Sally Munt, eds. 1997. Lesbian and Gay Studies: A Critical Introduction. London: Cassell. Print.

Mowlabocus, Sharif. 2010. Gaydar Culture: Gay Men, Technology and Embodiment in the Digital Age. Farnham/Burlington: Ashgate. Print.

Narrain, Arvind, and Gautam Bhan. 2005. Because I Have a Voice: Queer Politics in India. New Delhi: Yoda Press. Print.

Narrain, A., and M. Eldridge. 2009. The Right That Dares to Speak Its Name: Naz Foundation vs. Union of India and Others. Bangalore: Alternative Law Forum. Print.

Pullen, Christopher. 2010. Introduction. In LGBT Identity and Online New Media, ed. Christopher Pullen and Margaret Cooper, 1–13. London: Routledge. Print.

Rheingold, Howard. 1993. The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Print.

Roy, Sandip. 2003. From Khush List to Gay Bombay: Virtual Webs of Real People. In Mobile Cultures: New Media in Queer Asia, ed. Chris Berry, Fran Martin, and Audrey Yue, 180–200. Durham/London: Duke University Press. Print.

Roy, Piyush, and Mamta Sen. 2002. I Want to Break Free. Society, October 2002. Web. 4 Nov 2012.

Shahani, Parmesh. 2008. GayBombay: Globalisation, Love and Belonging in Contemporary India. New Delhi: Sage. Print.

Swiss, Thomas, and Andrew Hermann. 2000. The World Wide Web as Magic, Metaphor and Power. In The World Wide Web and Contemporary Cultural Theory, ed. Andrew Hermann and Thomas Swiss, 1–4. London: Routledge. Print.

Taylor, Affrica. 1997. A Queer Geography. In A Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader, ed. A. Medhurst and S. Munt, 3–19. London: Cassell. Print.

Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI). 2015. Annual Report 2013–14. Web. 22 Jan 2016.

Wakeford, Nina. 1997. Cyberqueer. In A Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader, ed. A. Medhurst and S. Munt, 343–359. London: Cassell. Print.

Weeks, Jeffrey. 2011. The Languages of Sexuality. New York/Abingdon: Routledge. Print.

Woodland, Randal. 2000. Queer Spaces, Modem Boys and Pagan Statues: Gay/Lesbian Identity and the Construction of Cyberspace. In The Cybercultures Reader, ed. David Bell and Barbara M. Kennedy, 417–431. London: Routledge. Print.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Dasgupta, R.K. (2018). Online Romeos and Gay-dia: Exploring Queer Spaces in Digital India. In: McNeil, E., Wermers, J., Lunn, J. (eds) Mapping Queer Space(s) of Praxis and Pedagogy. Queer Studies and Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64623-7_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64623-7_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-64622-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-64623-7

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)