Abstract

Searching for and dealing with health-related information on the Internet is a self-regulated process. Accordingly, how health-related information is selected, perceived, and produced by individuals in online informational environments may be affected by people’s motivation. In this chapter, we examine how motivated information processing influences how people deal with health-related information online. After a general introduction to the topic, the chapter deals with two aspects of the role of motivated processing of health-related information: On the one hand, people’s motivation is fueled by particular concepts that they hold about health in general, about health-related knowledge, and about specific health topics. Accordingly, we analyze in the first part of the chapter how people’s individual health concepts influence their information processing, discuss the impact of people’s health-related epistemological beliefs, and examine in what way their previous opinions of a health-related topic affect how they handle information. On the other hand, people’s motivations in information processing are related to their emotions. Thus, we discuss in the second part of the chapter how health-related information on the Internet can be a source of fear for laypeople and how patients who have received a medical diagnosis process information in order to cope with the threat they experience from their illness. In our presentation of research results we also analyze how people’s motivated information processing interacts with characteristics of the information they encounter in online environments. Finally, we sum up our findings and point out implications for future research and practical applications.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

The Internet provides users with a virtually unlimited selection of information from which they can acquire health information in a self-regulated manner. Users can decide without any professional guidance which link from a search engine result list they would like to follow, which comment in an online social support group they prefer to read, and at which point they want to leave one online platform and switch to another. The self-regulated nature of this information processing and acquisition in online informational environments suggests that motivation asserts a particularly strong impact on the informational outcomes of individuals’ online behavior. This is the case, since self-regulation in essence means that the guidelines for behavior and information selection come from the users themselves.

Researchers at the intersection of motivation and cognition have pointed out that motivational processes often have a major impact on people’s search for information, their evaluations of information, their memory and recall, as well as on their judgments and decision-making (Hart et al., 2009; Kruglanski, 1999; Kunda, 1999; Molden & Higgins, 2005; see also Kruglanski et al., 2012). Even though people’s information processing is sometimes driven by a requirement for accuracy, that is, by a need to come to a preferably correct assessment, accurate assessment is not always the end result. Striving for accuracy implies acquiring as much knowledge and understanding as possible about a particular topic. This approach may lead to largely unbiased information processing, but it requires assessable information along with people’s willingness and ability to engage in elaborate and unprejudiced handling of that information. Very often, however, information processing is influenced by people’s directed motivation, which is the endeavor to validate a certain idea or an existing judgment during information processing. This type of information processing is usually accompanied by the acquisition of information that confirms an individual’s own attitude, opinion, or impression, and that would presumably lead to achieving one’s own goals. Directed motivation thus leads to biased information processing, which we will refer to in this chapter as motivated information processing.

The self-regulated nature of dealing with information on the Internet suggests that online informational environments strongly promote motivated information processing. This is the case, in particular, when the domain that users deal with is personally relevant to them (Petty, Cacioppo, & Goldman, 1981). Personal relevance and, as a consequence, motivation are typically high when people search for and deal with health-related information. The Internet has developed into a huge and broad information source, above all in the health domain, as people increasingly use it for health-related concerns. Therefore, it is highly plausible that a person’s motivation has an impact on how he or she conducts health-related Internet searches and how they deal with the information they find online. At the same time, it is particularly important that laypeople are able to seek, understand, and use health information adequately (Jordan et al., 2013). In this chapter, we summarize research on the effects of motivated processing of health-related information. We address these processes in two separate sections. First, we present research on the motivated processing of health-related information that is influenced by the particular conceptions that individuals hold about health in general, about the nature and reliability of health-related knowledge, and about specific health-related topics, such as particular medical treatments. We thereby analyze how people’s individual health concepts influence their information processing, examine the role of their health-related epistemological beliefs, and describe how their previous opinions on a health-related topic influence the way they handle information. Second, we address the role of affect in motivated processing of health-related information. Here we analyze how searching for information on the Internet can cause fear in laypeople and how patients who have received a medical diagnosis handle online information due to the threat that results from their illness.

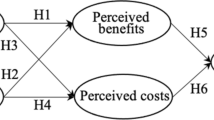

Throughout the entire presentation of research findings on motivated processing of health-related information, we also take into account and emphasize the particular characteristics of the information that Internet users encounter when searching for information in online environments. Our presentation makes clear that the processing of health-related information on the Internet is affected not only by the individual factors that people bring with them, but also by the characteristics of the presented information that frame the information as positive or negative, expressing a particular perspective toward the topic (see Fig. 4.1). In concluding, we provide an integrative discussion of the issues analyzed and address implications of the research findings presented in this chapter.

The Role of Individual Conceptions in Processing Health-Related Information

When individuals’ conceptions and understandings of the world come into play, their processing of information is not a purely rational process. Personal opinions and beliefs have a large influence on how information is dealt with. Information that corresponds to a person’s own opinions or beliefs are usually preferred over information that does not (Fischer, Greitemeyer, & Frey, 2008; Greitemeyer, 2014; Sassenberg, Landkammer, & Jacoby, 2014). Such non-conflicting information is more likely to be selected, considered to be more important, and more easily remembered than inconsistent information (Nickerson, 1998; Taber & Lodge, 2006). This phenomenon has been described explicitly for both laypeople and for medical experts (Bornstein & Emler, 2001; Hróbjartsson et al., 2012; Nickerson, 1998). Therefore, it is not surprising that the preference for information that is consistent with one’s own concepts also applies to how health-related information is handled on the Internet (for the role of cognitive conflicts in informational environments see also Buder, Buttliere, & Cress, 2017; Graesser, Lippert, & Hampton, 2017).

How people use the Internet to search for and further process health-related information is very often affected by their motivation to validate and maintain their beliefs, their knowledge, and their opinions. Such motivation has an impact on how individuals handle health-related information. In this context, the influence on information processing is mostly driven by a consistency principle (Greitemeyer, 2014; Nickerson, 1998). When individuals’ concepts are consistent with (online) information, individuals are more willing to process the information, evaluate the information better, and have a better attitude toward the information or the topic that the information deals with (Schweiger, Oeberst, & Cress, 2014). In this part of the chapter, we examine several factors that we have structured from general to more specific. First, these concepts include people’s general understanding of what they regard as “health” and what they think is important about health, that is, their individual health concepts (section “Individual Health Concepts in the Reception and Production of Information”). How individuals handle information also depends on their ideas about what health-related “knowledge” is. So information processing is influenced by people’s understanding of knowledge in the field of medicine and by their appraisal of the suitability of medical knowledge, that is, by their health-related epistemological beliefs (section “Epistemological Beliefs in Processing Health-Related Information”). Third, how people handle health-related information is influenced by their previous opinions on a particular health-related topic (section “Opinions in Processing Health-Related Information”).

Individual Health Concepts in the Reception and Production of Information

In the health domain, several actors (e.g., patients, physicians, or therapists) are involved who have to share information in different social contexts. A medical doctor, for instance, may talk to a patient to obtain information about the symptoms of a disease or to provide information about a medical intervention such as a particular surgery. To ensure a smooth process of diagnosis and therapeutic intervention, different health professionals have to combine their knowledge. This is very challenging, because different actors have diverse expertise, opinions, and beliefs. Even if they all have the same aim (i.e., maintaining and enhancing the health of a patient; Miles, 2005), this aim itself is open to interpretation. This is the case because different health concepts, that is, general concepts of health and how health is understood, coexist. Individual health concepts vary among different health professionals, between medical experts and patients as well as among different patients (Bensing, 2000; Domenech, Sánchez-Zuriaga, Segura-Ortí, Espejo-Tort, & Lisón, 2011; Larson, 1999; Patel, Arocha, & Kushniruk, 2002). Health concepts are influenced by the individual’s socialization and experience of illness and are assumed to be socially constructed (Makoul, 2011; Piko & Bak, 2006).

In the current Western health system, two different health concepts are prominent—the biomedical health concept and the biopsychosocial health concept. The biomedical health concept is a disease-oriented concept of health that is based on the International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (ICD; World Health Organization, 1992). The biopsychosocial health concept, in contrast, can be defined as an understanding of health in which the patient’s personal functioning and participation in daily life are central, a concept based on the International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF; World Health Organization, 2001). The classification systems that underlie these health concepts are both established in the health sector. Even though it is possible to use both classification systems equally (Simeonsson, Scarborough, & Hebbeler, 2006), the ICF is used primarily by health professionals who work in the field of rehabilitative medicine, like physiotherapists. Research has shown that the health concept can influence how patients and medical experts behave in health-related situations (Domenech et al., 2011).

In our own research, we investigated which of the two therapeutic health concepts physiotherapists have and how it develops over time (Bientzle, Cress, & Kimmerle, 2014a). We found that physiotherapists already had a strong biopsychosocial health concept in the early phases of vocational training, while a more pronounced biomedical concept only occurred in the course of their professional life. Moreover, we examined in several studies how the individual health concept influences the reception and production of health-related information. Regarding the reception of information, we found that information was rated as more relevant for the decision to participate in a medical intervention if the individual health concept and the health concept presented in the information were consistent with each other (Bientzle, Cress, & Kimmerle, 2015). Participants also acquired more knowledge when information corresponded to their individual health concept (Bientzle, Cress, & Kimmerle, 2013). These results are in line with research findings in the area of health communication that show that the reception of health-related information can be effectively supported by adapting information to the characteristics of the target group (Albada, Ausems, Bensing, & van Dulmen, 2009; Hawkins, Kreuter, Resnicow, Fishbein, & Dijkstra, 2008; Kreuter & Wray, 2003). Therefore, our research contributes to such health communication research by suggesting that patients and other laypeople are more willing to accept particular health-related information when their health concepts are taken into account in the presentation of this information.

For the production of information in online settings, we also found an important impact of people’s individual health concepts. Our research indicates that the individual health concept influences the way people communicate in online forums: Medical experts with a strongly pronounced biomedical health concept used more scientific words and fewer emotional words in their online communication than experts with a weak biomedical concept (Bientzle, Griewatz et al., 2015). When medical experts had the task of revising a text in a collaboratively developed wiki, which was either consistent or inconsistent with their own individual health concept, we found that they were more tolerant toward false conclusions in the text that was compatible with their own concept. In contrast, in the inconsistent wiki-text, medical experts tried to resolve false conclusions by revising scientific content more often (Bientzle, Cress, & Kimmerle, 2014b).

Epistemological Beliefs in Processing Health-Related Information

Assumptions regarding the structure and stability of knowledge also have an impact on the evaluation of information and the acquisition of knowledge (Hofer, 2001; Muis, 2004). These assumptions are called epistemological beliefs (EBs). EBs are defined as “the cognitions (i.e., understandings) individuals have on knowledge and knowing and determine how (new) knowledge is perceived and processed” (Roex & Degryse, 2007, p. 616). In that sense, EBs can be either more sophisticated or more simple. People with sophisticated EBs consider knowledge to be subjective and dynamic, whereas people with simple EBs regard knowledge as objective and static. Despite this seemingly clear dichotomy, EBs reflect a complex and multidimensional construct that is difficult to measure in its entirety.

The ability to handle information in a sophisticated and reflective way in the health domain is quite important, because the half-life of medical knowledge is steadily decreasing (Arbesman, 2012). Medical knowledge that is currently considered to be sound and valid can be tomorrow’s history, assessed as obsolete or even wrong. Thus, EBs play a major role in adequately handling information in the health context. Individuals with sophisticated health-related EBs are better able to process health-related information accurately than people with simple EBs. EBs are also dependent upon people’s educational level (Muis, Bendixen, & Haerle, 2006). In our own research we found that physiotherapy students and physiotherapy professionals have EBs of differing sophistication regarding knowledge in physiotherapy and regarding knowledge in medicine: Professionals assessed health-related knowledge as more subjective, constructed, and relative than did first-year students (Bientzle et al., 2014a).

EBs also play an important role in Internet search and the assessment of scientific and health-related information online (for an overview see Bråten, Britt, Strømsø, & Rouet, 2011). During an Internet search, various pieces of information from multiple sources with inconsistent or contradicting perspectives must be integrated and weighed against each other (Rouet, 2006). This may be particularly difficult for people with simple EBs. The necessity of grappling with contradictions might appear to be unreasonable for people who tend to underestimate the complexity of scientific knowledge. Research has shown that students with simple EBs were not able to process the information in a hypertext system as deeply as students with sophisticated EBs (Jacobson & Spiro, 1995). They also learned less and had poorer self-regulation abilities when they read hypertexts (Pieschl, Stahl, & Bromme, 2008). In our own research, we investigated how individuals deal with scientific medical information and found overall that individuals with sophisticated EBs recognized the tentativeness of medical information to a greater extent than people with simple EBs (Feinkohl, Flemming, Cress, & Kimmerle, 2016a). In particular, we illustrated that a lack of reliability in health-related information was more likely identified by participants with more sophisticated EBs than by participants with rather simple EBs (Kimmerle, Flemming, Feinkohl, & Cress, 2015). When Internet users deal with health-related information online, that is, when they read health news articles on the Internet and write user comments in online forums, people with sophisticated EBs address the tentativeness of medical information more often than Internet users with simple EBs (Feinkohl, Flemming, Cress, & Kimmerle, 2016b).

Furthermore, we could show that people with more sophisticated EBs were better in recalling health-related information (Feinkohl et al., 2016a). Overall, individuals with simple EBs were less critical in evaluating health-related information as presented in online media. These findings are in line with study results in other knowledge domains, which found that sophisticated EBs are also positively correlated with learning and academic performance (Hofer, 2001; Muis, 2004).

Health-related and medical knowledge and information are already in themselves unreliable constructs. When it comes to health-related information on the Internet, the reliability may even further decrease. This is the case when individuals (e.g., medical experts and laypersons) have to deal with knowledge from different sources and of different quality on the Internet. Moreover, alternative health communities on the Internet even have their own rules and quality standards to assess information (Kimmerle et al., 2013). Against this background, we might assume that sophisticated EBs may to some degree counteract people’s tendency to engage in motivated information processing. This becomes all the more important when people have to deal with health-related information on the Internet and need to evaluate the available information adequately.

Opinions in Processing Health-Related Information

When processing health-related information, individuals easily form an opinion about the topic they are dealing with (Burakgazi & Yildirim, 2014; Kimmerle & Cress, 2013). Newspaper articles or other media contributions dealing with health-related topics focus especially on the formation of opinion. Examples of such reports are media reports on new medical treatments such as deep brain stimulation (DBS). DBS involves a surgical procedure in which electrodes are implanted in the patient’s brain. It reduces tremors and other negative symptoms of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Researchers have also started to apply DBS as a treatment for drug addiction and other diseases, but its effectiveness is highly questionable and currently far from being entirely clear (Gilbert & Ovadia, 2011). Authors of media stories on DBS tend to over-simplify their reports in order to make them more easily understandable and free of conflicting information for readers without medical background knowledge (Kimmerle et al., 2015). As a consequence, these reports are often either framed overly positively, for example, by over-emphasizing the beneficial effects of DBS, or overly negatively through emphasis on risks or side effects (Gilbert & Ovadia, 2011; Racine, Waldman, Palmour, Risse, & Illes, 2007; see also Moynihan et al., 2000). This one-sided reporting is usually inadequate because health-related information, especially about novel medical findings, is often provisional, unreliable, inconsistent, contradictory, or controversial: That is to say, health-related research results are often “tentative” (Bromme & Goldman, 2014; Flemming, Feinkohl, Cress, & Kimmerle, 2015). This is a problem especially for laypeople, as they are often not aware of this tentativeness. Laypeople rather tend to perceive medical findings as clear, stable, reliable, or ever-lasting when they form their opinions about medical treatments from media content, which can lead to misconceptions and a false sense of clarity (Scharrer, Bromme, Britt, & Stadtler, 2012; Sinatra, Kienhues, & Hofer, 2014; van Deemter, 2010).

In our research, we investigated how prior opinions regarding DBS affected how individuals perceived the tentativeness of information on DBS. We found that, when participants had a negative opinion about DBS, they detected the tentativeness in a media report on DBS more often compared to those media consumers who read the report with a positive opinion about DBS (Kimmerle et al., 2015). Moreover, the amount of detected tentativeness declined if the information in the article was framed in a positive way. The two effects were independent of each other. In other words, participants with a negative opinion were more skeptical. They were less vulnerable to over-simplification and one-sided positive framing of health-related information than participants with a positive opinion. So, personal opinions have an influence on how information is processed when it comes to being critical toward health-related information as reported in the media. In particular, positive opinions seem to emphasize people’s bias of not recognizing the tentativeness of medical research findings.

We also found that prior opinions have an impact on how laypeople evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of medical interventions (Bientzle, Griewatz et al., 2015; Kimmerle, Bientzle, & Cress, 2017): Studies on the assessment of information about a mammography screening program showed that women who had a positive opinion of mammography screening in advance (and were thus willing to participate in the program anyway), also rated particular pieces of information representing the advantages of screening as more important than information that addressed disadvantages. Women who did not hold such a positive prior opinion on mammography screening did not differ in their assessment of advantages and disadvantages of mammography screening. So, the mere presentation of balanced information (both advantages and disadvantages) about a medical intervention does not guarantee that the information will be processed in a balanced way. Thus, health communicators, including medical professionals such as physicians as well as science journalists responsible for presenting health-related information, have to be highly aware of the role of people’s prior opinions in the processing of that information.

Our own findings address information processing of laypeople and (potential) patients, but experts are not immune to the influence of their own opinions either. For instance, Moreno and Johnston (2013) showed the occurrence of confirmation bias in the decision-making of healthcare providers. This is important, because opinion leaders within the healthcare system have an exceptional influence on the promotion of particular medical practices (Doumit, Gattellari, Grimshaw, & O’Brien, 2007). This is relevant, since the opinions of health professionals and those of patients may also interact in a complex way. In an online-consultation study, for instance, we found that after a consultation with a physician who provided information about risks and benefits of mammography screening, people had a more positive opinion about mammography if their needs had been made salient beforehand and when the physician used a need-oriented communication style (Fissler, Bientzle, Cress, & Kimmerle, 2015). If the physician used a purely fact-orientated communication style, in contrast, this led to an attitude change to a negative direction. It seems that not only the actual information itself but also the fit to a person’s opinions, needs, and expectations is of importance when laypeople process health-related information online (Bientzle, Griewatz et al., 2015). We have also shown that people adapt their opinion about a medical treatment more strongly to the opinion of the physician if the physician communicates in a patient-centered compared to a physician-centered way (Bientzle, Fissler, Cress, & Kimmerle, in press).

Summary

The research presented so far clearly indicates that people’s concepts and beliefs have a strong impact on how they process health-related information that they search for and find online. They prefer to process information that is consistent with their own concepts. This applies to their very general understanding of health (i.e., their individual health concepts), to their assumptions about the nature of health-related knowledge (i.e., their individual health-related EBs), and to their specific opinions toward particular health-related topics.

We have shown that the health concept is a factor that varies among patients and among different health professionals. In a series of studies, the fit between the individual health concept and the health concept in which information was presented was identified as a factor that influenced the reception and production of health-related information on the Internet. The results seem to be crucially relevant for inter-professional information exchange and health communication issues in the health system. Our studies indicate that it is very important to consider people’s health concepts very thoroughly, regardless of whether we are examining situations of mere information processing or, further, the production of information. Both processes are strongly influenced by what people regard as relevant when they talk about health. When patients and other medical laypeople search the Internet for health-related information, they should be aware of their own understanding of health and of their ultimate goal in this search process.

Individual EBs vary between students and health professionals and among different health domains. This influences the processing of health-related information, which is often tentative and ill-structured. A certain level of sophistication of EBs seems to counteract the motivated processing of health-related information. Moreover, dealing with information on the Internet entails further challenges, like the integration of inconsistent information sources and perspectives. Opinions also have a strong impact on how people handle health-related information. They tend to process information in a way that is consistent with their prior opinions. If individuals have a positive opinion about a specific health-related topic, they tend to underestimate the tentativeness of the pertinent medical knowledge on this topic. Our research shows that this distortion of the information processing may in part be compensated for in those Internet users who possess more sophisticated EBs concerning medical knowledge.

How individuals process health-related information is not only influenced by people’s concepts of the world; how people search for and perceive health-related information can also be influenced by their emotions and affective reactions. The following section addresses the role of affect in the motivated processing of health-related information on the Internet.

The Role of Affect in Processing Health-Related Information

Health-related Internet searches may have different implications for individuals with respect to their feelings. In this section, we address two different roles that emotions may play in processing health information in online environments. Due to a motivated processing of information, some individuals may feel worse than before finding the information, while other individuals may find the online information helpful and feel better. In two sub-sections, we present empirical evidence for both possibilities and describe under which conditions individuals feel worse or better when searching the Internet for health-related information. Feeling worse can result from a person’s focus on negative information during a health-related Internet search. This focus on negative information may arise from a sort of cyberchondria (section “Health-Related Internet Search and Cyberchondria”). Individuals who have been diagnosed with a particular disease, in contrast, are motivated to process information on this disease in a goal-oriented way and tend to focus on positive information that they deem helpful for their situation (section “Information Processing of Diagnosed Patients on the Internet”).

Health-Related Internet Search and Cyberchondria

Having access to health-related information online can sometimes evoke fear in laypeople. It seems to be very common that individuals conduct Internet searches when experiencing unfamiliar states of their bodies or when there is information in the media warning about a potential epidemic (e.g., Ginsberg et al., 2009). Such searches for information often lead to the fear that one is sick, and individuals find evidence on the Internet that the slightest symptoms are an indication of severe illness. Based on this anecdotal evidence, White and Horvitz (2009) coined the term cyberchondria to label the phenomenon that individuals frequently encounter negative information during health-related Internet searches—in particular when they are searching for the sources of physical symptoms. Even though the empirical research on the causes and antecedents of this phenomenon is still in its very early stages, (weak forms of) cyberchondria seem to occur quite frequently (Muse, McManus, Leung, Meghreblia, & Williams, 2012).

In our own research, we aimed to study whether the affective content of online information and how it is presented are facilitating factors in this fear of being sick. To be more precise, we wanted to gain insight into the characteristics of online information that contribute to fear and information processing of negative information among users. The results could help to understand and, ultimately, to prevent, biased information processing. We conducted experiments in which laypeople read reports about a specific, health-related treatment, namely DBS (see section “Opinions in Processing Health-Related Information”). DBS is applied to patients with disabling neurological symptoms, such as those of Parkinson’s disease. It does not cure them but, if applied successfully, it delivers substantial relief from major symptoms. In reports about DBS, the mere description of the surgery can elicit uneasy feelings in laypeople and supply them with information they experience negatively. In particular, that the brain surgery is partly undertaken when the patient is conscious, and that it may have the side effect of changing a patient’s personality, produce emotional responses in laypeople.

Besides the content of information sources on DBS, the way such reports on DBS are written can influence laypeople’s information processing as well. In particular, journalists reporting on DBS frequently use personalization as a technique to increase the attractiveness of their reports. They introduce a fictitious or a real protagonist at the beginning of the text to make the storyline more vivid and interesting. In the case of medical treatments, patients and doctors are prototypical protagonists. Most likely, reports with patients as protagonists are more personally dramatic to laypeople than reports of doctors applying DBS, as most laypeople have at some time experienced being a patient. As a consequence, reports with patients as protagonists dramatize the patient’s perspective for laypeople and cause them to identify with the patient protagonists, taking on their perspective (Batson & Shaw, 1991; Batson et al., 1988). Such patient reports often simultaneously convey negative information, for example, about the irksome procedure of the brain surgery. As a result, such negative information elicits negative emotions in laypeople. Given the fact that people preferentially process affect-congruent information (e.g., Blaney, 1986; Bower, 1981), feeling negative about a medical treatment would foster memory with a preference for negative information about this treatment.

Thus, we hypothesized that reports on DBS with patients as protagonists would elicit a stronger negative affect and, in turn, better memory of negative information, than reports with doctors as protagonists. Following this reasoning, reports with patients as protagonists reporting on more positive experiences with DBS should then certainly also elicit a more positive affect. However, given that this study focused on a treatment that can at best reduce—not cure—symptoms of a severe illness, we mainly expected effects with regard to negative emotions in recipients. This hypothesis was tested in a study (Sassenrath, Greving, & Sassenberg, 2017) in which participants first listened to an audio report about DBS. We applied this procedure because we had found in a previous study that an audio presentation increased the vividness of reports as well as the affective responses (Sassenrath, Greving, & Sassenberg, 2016b). These audio reports about DBS either involved a patient or a doctor as the protagonist. Afterwards, we assessed affect. Next, participants read additional information about DBS. After working for 5 min on a different, unrelated task, participants were unexpectedly asked to recall as much information about DBS as possible. In line with the prediction, participants who had heard reports with patients as protagonists demonstrated more negative and less positive affect than those who had heard reports with doctors as protagonists. Moreover, after listening to reports with patients as protagonists, the negative affect further led to a focus on negative information (i.e., more recall of negative information and less recall of positive information). In sum, these findings indicate that reports on medical treatments of severe illnesses using patients as protagonists elicit more negative affect and a preferential processing of negative information compared to reports using doctors as protagonists.

In another study (Sassenrath, Greving, & Sassenberg, 2017), we aimed to rule out the possibility that the effects reported above resulted from the fact that the text focused on one patient as a protagonist rather than on patients in general. To this end, we compared participants’ affective responses and memory after listening to a report with one patient as the protagonist (reporting from a first-person perspective), versus a report with the same content but using wording of patients’ experiences in general (reporting form a third-person perspective). Otherwise, the same paradigm was applied as in the study described above. Again, patients’ reports on their experiences with DBS from a first-person perspective elicited stronger emotions and—indirectly via negative affect—recall of more negative information about DBS than patients’ reports from a third-person perspective.

Taken together, these studies suggest that the personalization features of patients’ reports contribute to the development of negative affect and memory of negative information in laypeople. For Internet users searching for health-related information, these findings imply that reports using individuals as protagonists who are similar to users cause users to develop fear as a result of their preferential processing of negative information. In the same way, personal online reports (e.g., in online social support groups) are very likely to elicit the same kind of identification and, thus, similar fearful effects to news reports. More generally, the vividness of reports is more likely to evoke affective responses. In other words, patient protagonists and other features that increase identification and perspective taking, or vividness in news reports about diseases, are likely to fuel fear and vigilance toward negative information in Internet users, and should, thus, be applied with caution.

Information Processing of Diagnosed Patients on the Internet

Motivated information processing may also come into play for patients who have been diagnosed with a certain illness. An illness is an undesirable state, and individuals are usually highly motivated to overcome this state. Reduced resources as a result of the illness paired with high motivation to overcome the illness usually lead to threat appraisals (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1996). Threat is not necessarily understood in the sense of an existential threat, but in the sense of a threat to achieving goals, or simply a threat to being in a desirable state (i.e., to being healthy). Threatened individuals search for information that may help them to overcome the illness, because they feel they lack the resources to do so on their own. Threat may, therefore, lead to the preferential processing of positive information. According to the counter-regulation principle (Rothermund, 2011), individuals allocate their attention and their processing capacity to stimuli with a valence opposing their current motivational state: In a positive motivational state, negative information is preferably processed, whereas in a negative motivational state, positive information is preferably processed. Threat is a negative motivational state that individuals clearly aim to change. There is plenty of evidence for the counter-regulation principle. Individuals in a negative motivational state, such as threat, preferentially process positive information, and (less relevant in the current context) individuals in a positive motivational state preferentially process negative information. These effects occur for a range of different psychological processes, such as attention and complex judgments and decisions (e.g., Koranyi & Rothermund, 2012; Rothermund, Gast, & Wentura, 2011; Sassenberg, Sassenrath, & Fetterman, 2015; Schwager & Rothermund, 2014; for the role of emotion regulation in informational environments see also Azevedo et al., 2017).

Counter-regulation is, due to its unconscious nature, likely to apply to conditions characterized by allowing self-regulation that makes it possible for individuals to deal with information in a manner that suits their needs. This is especially the case for the unguided and iterative multi-step process of Internet searches (e.g., Brand-Gruwel, Wopereis, & Walraven, 2009). Therefore, it seems likely that an information search on the Internet would also be affected by threat. To be more precise, counter-regulation should affect all of the steps of an Internet search process, that is, (a) the generation of search terms, (b) the selection of links, (c) the time spent on webpages, (d) the encoded information, (e) the judgment about a topic made after the information search, and (f) the recall of information. Overall, we predicted a bias toward positive information in all these steps when individuals felt threatened, compared to when they did not. These predictions were tested in a series of five experiments (Greving & Sassenberg, 2015; Greving, Sassenberg, & Fetterman, 2015) using different manipulations of threat and different materials. For ethical reasons, we primarily manipulated the threat and only conducted one longitudinal field study with real patients (Sassenberg & Greving, 2016).

In a first study, we tested the prediction that threat would lead to the generation of more positive search terms (Greving & Sassenberg, 2015, Experiment 1). In order to induce threat, participants were first asked to think about a current demand in their life they had trouble coping with. In a control condition, they were asked to think about a typical situation in their life. Afterwards, participants were asked to generate search terms for an Internet search on living organ donation. In line with the prediction, more positive search terms were generated by individuals who had thought about a current threat than by participants in the control condition.

In a second study, we induced a health threat to test the impact of threat on the selection of links from a search engine result page (SERP; Greving et al., 2015, Experiment 2). To this end, a well-established manipulation by Ditto and Lopez (1992; Ditto, Scepansky, Munro, Apanovitch, & Lockhart, 1998) was applied. Participants took an ostensible saliva test for a newly discovered enzyme deficit. In the threat condition, they learnt that they had this deficit, whereas in the control condition participants were informed that the test had not worked out. Afterwards, participants received a SERP regarding the enzyme deficit. This SERP was presented in the format of a 4 × 4 table to avoid the possibility that participants would merely select the links at the top (because they assumed that they were more relevant as is the case with Google result pages). Participants had to choose 8 out of 16 links. As assumed, participants in the threat condition chose a higher proportion of positive links than participants in the control condition.

A third experiment studied the whole Internet search process (Greving et al., 2015, Experiment 1). After recalling a threatening or, in the control condition, an ordinary situation related to an upcoming examination, participants conducted a free Internet search for 10 min. The Internet search process was logged and the pages on the computer screens were recorded. Participants in the threat condition looked longer at positive pages and also recalled more positive information than participants in the control condition. This effect was also replicated in a controlled laboratory experiment in which a SERP was completely pre-programmed (Greving & Sassenberg, 2016).

A fourth follow-up study tested whether the recall of positive information was also more likely when the reading material was held constant across conditions (Greving et al., 2015, Experiment 3), which had not been the case in the previous study. Therefore, a threat (vs. control) was induced with a similar recall procedure as in the first search term generation study. Afterwards, individuals read a fixed set of texts taken from an Internet search on living organ donation that did not differ between conditions. Participants in the threat condition in fact recalled more positive information from these texts than participants in the control condition. This demonstrated that the impact of threat on the recall of positive information did not depend on the amount and valence of the material that the threatened individuals were assessing. In this study, participants also judged the risks and benefits associated with donating living organs. In line with our expectation that threat leads to a positive bias, participants in the threat condition also judged living organ donation to be more beneficial (but not less risky).

Finally, threat not only affects the search process that is mostly characterized by encoding information, but also the retrieval of information at the end of the search process. Therefore, a final experimental study (Greving & Sassenberg, 2015, Experiment 2) used the materials of the study summarized above, but reversed the order of the elements: Participants first read a text on living organ donation, then a threat was manipulated, and afterwards participants were asked to recall information from the text. This procedure allowed us to study the mere retrieval effects of a threat. Again, supporting the idea that threat leads to preferential processing of positive information, more positive information was in fact recalled from memory when a threat was induced after reading the text than when no threat was induced.

In sum, these studies provided evidence that threat creates a tendency toward positive bias in all of the steps of the multistep-process of information search on the Internet. Since it is desirable to complement study sets of internally valid experiments with externally valid field studies, we conducted a longitudinal field study on the outcomes of Internet search behavior resulting from how actual patients perceived their own health state (Sassenberg & Greving, 2016). Patients with chronic inflammatory bowel disease were recruited for a two-wave longitudinal study with a 7-month lag. At both points in time, the frequency of their health-related Internet search, the severity of the illness as an indicator of threat, and health-related optimism as a relevant outcome measure were assessed via self-reports. It was predicted that among patients using the Internet frequently to search for health-related information, the findings from the experimental studies would be replicated—more threat would lead to more health-related optimism. No such effect, in contrast, was expected for patients using the Internet rarely for this purpose. Indeed, the interaction of threat and frequency of health-related Internet use at the first measurement point predicted health-related optimism at the second measurement point after 7 months (controlling for optimism at the first measurement point). The pattern underlying the interaction effect fit the prediction. We were thus also able to show in a field setting that a health threat led to a stronger positivity bias (more health-related optimism) among individuals using the Internet frequently to acquire health information. Stated differently, among patients with a greater health threat, more frequent Internet searches regarding their health led to more optimism. In contrast, among patients with a smaller health threat, the opposite effect occurred, indicating that they were less optimistic about their health. Additional analyses provided no evidence for such an effect for other external sources of information.

We can conclude that patients searching for information regarding their (diagnosed) disease are likely to be subject to a positivity bias—in particular if the disease is threatening to them. On the one hand, the positivity bias is a means of emotionally coping with the negative psychological side effects of disease, because the sense of threat will most likely be held under control by focusing on positive information. It follows that patients experiencing a threat might be particularly prone to information or advertisements for products promising a cure, even if the promises are invalid or inaccurate.

Summary

The research described in this section has shown that a motivated processing of health-related information on the Internet may have negative effects, in particular regarding people’s emotions and their preferential processing of negative information. Already the term cyberchondria itself points to the fact that strong forms of health-related anxiety induced by an Internet search are categorized as a type of disorder (a specific type of obsessive-compulsive disorder; Norr, Oglesby et al., 2015). Thus, anxiety as an outcome of a health-related Internet search is a dysfunctional and undesirable response, whereas the positivity bias in counter-regulation demonstrated by the information processing of diagnosed patients may be a functional and healthy response to negative motivational states (Rothermund, 2011). We have shown that this positivity bias, however, only occurs when individuals are currently in a negative motivational state and have a strong desire to change their situation. This conclusion fits the results from the longitudinal study on patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Those with a serious illness and frequent episodes, who are likely to see their illness as a threat, showed a positive bias as an outcome of frequent Internet searches, whereas those with less sense of threat and infrequent episodes showed the opposite effect of Internet searches. To mention one implication of these processes, it could be that patients gleaning information from the Internet might confront doctors with their unrealistically positive views of their own situation. This is a possibility that requires attention and doctors need to be prepared. Otherwise, patients’ health might suffer because they might, as an example, stop a treatment too early (for a detailed discussion of the ethical implications of these findings see Sassenberg & Wiesing, 2016).

Conclusion

Online informational environments promote the impact of motivated information processing. This is particularly true when personal relevance is high, as is the case when people search for and deal with health-related information. The empirical studies presented in this chapter illustrate very clearly that how people handle health-related information on the Internet is strongly influenced by their particular motives. When people process health-related information in online situations, they often have the desire to validate their prior knowledge, opinions, and judgments. As a consequence, they deal with online information in a way that allows them to confirm their existing understanding of or attitude toward a health topic. We have presented much empirical evidence for how this may result in biased information processing. In addition, our presentation of research findings regarding cyberchondria and the behavior of diagnosed patients makes it clear that experiencing anxiety (as a consequence of an information search on the Internet) and threat (as a consequence of being sick) also frequently results in biased processing and representation of information.

All things considered, comprehending people’s processing of health-related information on the Internet is even more complicated, since it is not only influenced by their motivation but also by particular characteristics of the information (see Fig. 4.1). As our research has shown, these characteristics comprise several aspects. How people deal with health-related information also depends on the specific perspective on a health topic that is represented in the information in an online setting. For example, it makes a difference for information processing when people with a biomedical or a biopsychosocial individual health concept encounter information that also expresses a biomedical or a biopsychosocial view on health, which is either compatible with or contrary to their own point of view. People with a particular motivation also process information differently when it is framed in a positive way than when it is framed negatively. The same applies to health information on the Internet that either emphasizes the advantages or the disadvantages of a particular medical treatment. The particular focus of the health information interacts strongly with people’s prior opinions on the topic. Moreover, the way in which the information is presented is relevant. For example, it makes a difference whether health professionals in an online consultation take the personal needs of a patient into account or are merely focused on their medical issues.

In medical news reports, the presentation of the information is also essential for the processing of this information. For example, a report that explicitly addresses the tentativeness of medical research findings may support the readers in recognizing and understanding this tentativeness. This is particularly important for those readers who possess rather simple epistemological beliefs. Finally, it makes a difference to what extent a report uses the personalization of health information. A report may use either patients or doctors as protagonists in depicting a health story, or it may apply a first- or a third-person perspective to make the story more or less personal. How Internet users who search for health information will react to medical news depends on whether or not such reports aim to convey a vivid and dramatic picture of a health-related topic to draw more attention to it.

Due to this interplay between individual factors on the one hand and the characteristics of information on the other, future research should make an attempt to take both aspects into consideration at the same time. This chapter is a first step in providing an integrative view of both aspects. This interplay is an issue that should also be taken into account in applied situations. Health communicators, physicians, and health journalists should be aware of these interactions between individual factors and ways of communicating. Only then can laypeople be adequately supported in their self-regulated processing of health-related information in online environments.

References

Albada, A., Ausems, M. G., Bensing, J. M., & van Dulmen, S. (2009). Tailored information about cancer risk and screening: A systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling, 77, 155–171. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.005

Arbesman, S. (2012). The half-life of facts: Why everything we know has an expiration date. New York, NY: Penguin.

Azevedo, R., Millar, G. C., Taub, M., Mudrick, N. V., Bradbury, A. E., & Price, M. J. (2017). Using data visualizations to foster emotion regulation during self-regulated learning with advanced learning technologies. In J. Buder & F. W. Hesse (Eds.), Informational environments: Effects of use, effective designs (pp. 225–247). New York: Springer.

Batson, C. D., Dyck, J. L., Brandt, J. R., Batson, J. G., Powell, A. L., McMaster, M. R., & Griffitt, C. (1988). Five studies testing two new egoistic alternatives to the empathy-altruism hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55, 52–77. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.55.1.52

Batson, C. D., & Shaw, L. L. (1991). Evidence for altruism: Toward a pluralism of prosocial motives. Psychological Inquiry, 2, 107–122. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0202_1

Bensing, J. (2000). Bridging the gap: The separate worlds of evidence-based medicine and patient-centered medicine. Patient Education and Counseling, 39, 17–25. doi:10.1016/S0738-3991(99)00087-7

Bientzle, M., Cress, U., & Kimmerle, J. (2013). How students deal with inconsistencies in health knowledge. Medical Education, 47, 683–690. doi:10.1111/medu.12198

Bientzle, M., Cress, U., & Kimmerle, J. (2014a). Epistemological beliefs and therapeutic health concepts of physiotherapy students and professionals. BMC Medical Education, 14, 208. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-14-208

Bientzle, M., Cress, U., & Kimmerle, J. (2014b). The role of inconsistencies in collaborative knowledge construction. In Proceedings of the 11th international conference of the learning sciences (Vol. I, pp. 102–109). Boulder, CO: International Society of the Learning Sciences.

Bientzle, M., Cress, U., & Kimmerle, J. (2015). The role of tentative decisions and health concepts in assessing information about mammography screening. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 20, 670–679. doi:10.1080/13548506.2015.1005017

Bientzle, M., Fissler, T., Cress, U., & Kimmerle, J. (in press). The impact of physicians’ communication styles on evaluation of physicians and information processing: A randomized study with simulated video consultations on contraception with an intrauterine device. Health Expectations. It’s still in press. doi:10.1111/hex.12521

Bientzle, M., Griewatz, J., Kimmerle, J., Küppers, J., Cress, U., & Lammerding-Koeppel, M. (2015). Impact of scientific versus emotional wording of patient questions on doctor-patient communication in an Internet forum: A randomized controlled experiment with medical students. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17, e268. doi:10.2196/jmir.4597

Blaney, P. H. (1986). Affect and memory: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 99, 229–246. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.99.2.229

Blascovich, J., & Tomaka, J. (1996). The biopsychosocial model of arousal regulation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 28, 1–51.

Bornstein, B. H., & Emler, A. C. (2001). Rationality in medical decision making: A review of the literature on doctors’ decision-making biases. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 7, 97–107. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2753.2001.00284.x

Bower, G. H. (1981). Mood and memory. American Psychologist, 36, 129–148. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.36.2.129

Bråten, I., Britt, M. A., Strømsø, H. I., & Rouet, J. F. (2011). The role of epistemic beliefs in the comprehension of multiple expository texts: Toward an integrated model. Educational Psychologist, 46, 48–70. doi:10.1080/00461520.2011.538647

Brand-Gruwel, S., Wopereis, I., & Walraven, A. (2009). A descriptive model of information problem solving while using internet. Computers & Education, 53, 1207–1217. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2009.06.004

Bromme, R., & Goldman, S. R. (2014). The public’s bounded understanding of science. Educational Psychologist, 49, 59–69.

Buder, J., Buttliere, B., & Cress, U. (2017). The role of cognitive conflicts in informational environments: Conflicting evidence from the learning sciences and social psychology? In J. Buder & F. W. Hesse (Eds.), Informational environments: Effects of use, effective designs (pp. 53–74). New York: Springer.

Burakgazi, S. G., & Yildirim, A. (2014). Accessing science through media: Uses and gratifications among fourth and fifth graders for science learning. Science Communication, 36, 168–193.

Ditto, P. H., & Lopez, D. F. (1992). Motivated skepticism: Use of differential decision criteria for preferred and nonpreferred conclusions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 568–584. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.568

Ditto, P. H., Scepansky, J. A., Munro, G. D., Apanovitch, A. M., & Lockhart, L. K. (1998). Motivated sensitivity to preference-inconsistent information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 53–69. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.53

Domenech, J., Sánchez-Zuriaga, D., Segura-Ortí, E., Espejo-Tort, B., & Lisón, J. F. (2011). Impact of biomedical and biopsychosocial training sessions on the attitudes, beliefs, and recommendations of health care providers about low back pain: A randomised clinical trial. Pain, 152, 2557–2563. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.023

Doumit, G., Gattellari, M., Grimshaw, J., & O’Brien, M. (2007). Local opinion leaders: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database System Review, 1.

Feinkohl, I., Flemming, D., Cress, U., & Kimmerle, J. (2016a). The impact of epistemological beliefs and cognitive ability on recall and critical evaluation of scientific information. Cognitive Processing, 17, 213–223. doi:10.1007/s10339-015-0748-z

Feinkohl, I., Flemming, D., Cress, U., & Kimmerle, J. (2016b). The impact of personality factors and preceding user comments on the processing of research findings on deep brain stimulation: A randomized controlled experiment in a simulated online forum. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18, e59.

Fischer, P., Greitemeyer, T., & Frey, D. (2008). Self-regulation and selective exposure: The impact of depleted self-regulation resources on confirmatory information processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 382–395. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.3.382

Fissler, T., Bientzle, M., Cress, U., & Kimmerle, J. (2015). The impact of advice seekers’ need salience and doctors’ communication style on attitude and decision making: A web-based mammography consultation role play. JMIR Cancer, 1, e10. doi:10.2196/cancer.4279

Flemming, D., Feinkohl, I., Cress, U., & Kimmerle, J. (2015). Individual uncertainty and the uncertainty of science: The impact of perceived conflict and general self-efficacy on the perception of tentativeness and credibility of scientific information. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01859

Gilbert, F., & Ovadia, D. (2011). Deep brain stimulation in the media: Over-optimistic media portrayals call for a new strategy involving journalists and scientists in the ethical debate. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 5(16). doi:10.3389/fnint.2011.00016

Ginsberg, J., Mohebbi, M. H., Patel, R. S., Brammer, L., Smolinski, M. S., & Brilliant, L. (2009). Detecting influenza epidemics using search engine query data. Nature, 457, 1012–1014. doi:10.1038/nature07634

Graesser, A. C., Lippert, A., & Hampton, D. (2017). Successes and failures in building learning environments to promote deep learning: The value of conversational agents. In J. Buder & F. W. Hesse (Eds.), Informational environments: Effects of use, effective designs (pp. 273–298). New York: Springer.

Greitemeyer, T. (2014). I am right, you are wrong: How biased assimilation increases the perceived gap between believers and skeptics of violent video game effects. PLoS One, 9, e93440. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0093440

Greving, H., & Sassenberg, K. (2015). Counter-regulation online: Threat biases retrieval of information during Internet search. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 291–298.

Greving, H., & Sassenberg, K. (2016). When positive information is preferred: Counter-regulating threat during Internet search. Unpublished manuscript, Leibniz-Institut für Wissensmedien, Tübingen, Germany.

Greving, H., Sassenberg, K., & Fetterman, A. (2015). Counter-regulating on the internet: Threat elicits preferential processing of positive information. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 21, 287–299.

Hart, W., Albarracín, D., Eagly, A. H., Brechan, I., Lindberg, M. J., & Merrill, L. (2009). Feeling validated versus being correct: A meta-analysis of selective exposure to information. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 555–588.

Hawkins, R. P., Kreuter, M., Resnicow, K., Fishbein, M., & Dijkstra, A. (2008). Understanding tailoring in communicating about health. Health Education Research, 23, 454–466. doi:10.1093/her/cyn004

Hofer, B. K. (2001). Personal epistemology research: Implications for learning and teaching. Educational Psychology Review, 13, 353–383. doi:10.1023/A:1011965830686

Hróbjartsson, A., Thomsen, A. S. S., Emanuelsson, F., Tendal, B., Hilden, J., Boutron, I., … Brorson, S. (2012). Observer bias in randomised clinical trials with binary outcomes: Systematic review of trials with both blinded and non-blinded outcome assessors. British Medical Journal, 344, e1119. doi:10.1136/bmj.e1119

Jacobson, M. J., & Spiro, R. J. (1995). Hypertext learning environments, cognitive flexibility, and the transfer of complex knowledge: An empirical investigation. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 12, 301–333.

Jordan, J. E., Buchbinder, R., Briggs, A. M., Elsworth, G. R., Busija, L., Batterham, R., & Osborne, R. H. (2013). The health literacy management scale (HeLMS): A measure of an individual’s capacity to seek, understand, and use health information within the healthcare setting. Patient Education and Counseling, 91, 228–235.

Kimmerle, J., Bientzle, M., & Cress, U. (2017). “Scientific evidence is very important for me”: The impact of behavioral intention and the wording of user inquiries on replies and recommendations in a health-related online forum. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 320–327.

Kimmerle, J., & Cress, U. (2013). The effects of TV and film exposure on knowledge about and attitudes toward mental disorders. Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 931–943.

Kimmerle, J., Flemming, D., Feinkohl, I., & Cress, U. (2015). How laypeople understand the tentativeness of medical research news in the media: An experimental study on the perception of information about deep brain stimulation. Science Communication, 37, 173–189. doi:10.1177/1075547014556541

Kimmerle, J., Thiel, A., Gerbing, K. K., Bientzle, M., Halatchliyski, I., & Cress, U. (2013). Knowledge construction in an outsider community: Extending the communities of practice concept. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 1078–1090. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.09.010

Koranyi, N., & Rothermund, K. (2012). Automatic coping mechanisms in committed relationships: Increased interpersonal trust as a response to stress. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48, 180–185.

Kreuter, M. W., & Wray, R. J. (2003). Tailored and targeted health communication: Strategies for enhancing information relevance. American Journal of Health Behavior, 27, 227–232.

Kruglanski, A. W. (1999). Motivation, cognition, and reality: Three memos for the next generation of research. Psychological Inquiry, 10, 54–58.

Kruglanski, A. W., Bélanger, J. J., Chen, X., Köpetz, C., Pierro, A., & Mannetti, L. (2012). The energetics of motivated cognition: A force-field analysis. Psychological Review, 119, 1–20.

Kunda, Z. (1999). Social cognition: Making sense of people. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Larson, J. S. (1999). The conceptualization of health. Medical Care Research and Review, 56, 123–136. doi:10.1177/107755879905600201

Makoul, G. (2011). Physician understanding of patient health beliefs. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26, 574–574. doi:10.1007/s11606-011-1691-z

Miles, S. H. (2005). The Hippocratic oath and the ethics of medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Molden, D. C., & Higgins, E. T. (2005). Motivated thinking. In K. J. Holyoak & R. G. Morrison (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of thinking and reasoning (pp. 295–320). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Moreno, J. P., & Johnston, C. A. (2013). The role of confirmation bias in the treatment of diverse patients. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 7, 20–22.

Moynihan, R., Bero, L., Ross-Degnan, D., Henry, D., Lee, K., Watkins, J., … Soumerai, S. B. (2000). Coverage by the news media of the benefits and risks of medications. New England Journal of Medicine, 342, 1645–1650.

Muis, K. R. (2004). Personal epistemology and mathematics: A critical review and synthesis of research. Review of Educational Research, 74, 317–377. doi:10.3102/00346543074003317

Muis, K. R., Bendixen, L. D., & Haerle, F. C. (2006). Domain-generality and domain-specificity in personal epistemology research: Philosophical and empirical reflections in the development of a theoretical framework. Educational Psychology Review, 18, 3–54. doi:10.1007/s10648-006-9003-6

Muse, K., McManus, F., Leung, C., Meghreblia, B., & Williams, J. M. G. (2012). Cyberchondriasis: Fact or fiction? A preliminary examination of the relationship between health anxiety and searching for health information on the Internet. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26, 189–196.

Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, 2, 175–220. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175

Norr, A. M., Oglesby, M. E., Raines, A. M., Macatee, R. J., Allan, N. P., & Schmid, N. B. (2015). Relationships between cyberchondria and obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions. Psychiatry Research, 230, 441–446.

Patel, V. L., Arocha, J. F., & Kushniruk, A. W. (2002). Patients’ and physicians’ understanding of health and biomedical concepts: Relationship to the design of EMR systems. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 35, 8–16. doi:10.1016/S1532-0464(02)00002-3

Petty, R. E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Goldman, R. (1981). Personal involvement as a determinant of argument-based persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 847–855.

Pieschl, S., Stahl, E., & Bromme, R. (2008). Epistemological beliefs and self-regulated learning with hypertext. Metacognition and Learning, 3, 17–37.

Piko, B. F., & Bak, J. (2006). Children’s perceptions of health and illness: Images and lay concepts in preadolescence. Health Education Research, 21, 643–653. doi:10.1093/her/cyl034

Racine, E., Waldman, S., Palmour, N., Risse, D., & Illes, J. (2007). ‘Currents of hope’: Neurostimulation techniques in U.S. and U.K. print media. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 16, 312–316.

Roex, A., & Degryse, J. (2007). Introducing the concept of epistemological beliefs into medical education: The hot-air-balloon metaphor. Academic Medicine, 82, 616–620. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180556abd

Rothermund, K. (2011). Counter-regulation and control-dependency. Social Psychology, 42, 56–66.

Rothermund, K., Gast, A., & Wentura, D. (2011). Incongruency effects in affective processing: Automatic motivational counter-regulation or mismatch-induced salience? Cognition and Emotion, 25, 413–425.

Rouet, J. F. (2006). The skills of document use: From text comprehension to Web-based learning. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Sassenberg, K., & Greving, H. (2016). Internet searching about disease elicits a positive perception of own health when severity of illness is high: A longitudinal questionnaire study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(3), e56.

Sassenberg, K., Landkammer, F., & Jacoby, J. (2014). The influence of regulatory focus and group vs. individual goals on the evaluation bias in the context of group decision making. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 54, 153–164.

Sassenberg, K., Sassenrath, C., & Fetterman, A. K. (2015). Threat≠ prevention, challenge≠ promotion: The impact of threat, challenge and regulatory focus on attention to negative stimuli. Cognition and Emotion, 29, 188–195.

Sassenberg, K., & Wiesing, U. (2016). Internet-informierte Patienten–Empirische Evidenz für einseitige Informationsverarbeitung und ihre medizinethischen Implikationen. Zeitschrift für Medizinische Ethik, 62, 299–311.

Sassenrath, C., Greving, H., & Sassenberg, K. (2016a). Are you concerned? Using patients as protagonists in reports on medical treatments affects recipients’ affective experiences and memory performance stronger than using doctors as protagonists. Unpublished manuscript, Leibniz-Institut für Wissensmedien, Tübingen, Germany.

Sassenrath, C., Greving, H., & Sassenberg, K. (2016b). The impact of communication channel on affect and memory. Unpublished data, Leibniz-Institut für Wissensmedien, Tübingen, Germany.

Sassenrath, C., Sassenberg, K., & Greving, H. (2017). It has to be first-hand: The effect of first-person testimonials in medical communication on recipients’ emotions and memory. Cogent Medicine, 4(1), 1354492.

Bromme, R., & Goldman, S. R. (2014). The public’s bounded understanding of science. Educational Psychologist, 49, 59–69.

Schwager, S., & Rothermund, K. (2014). On the dynamics of implicit emotion regulation: Counter-regulation after remembering events of high but not of low emotional intensity. Cognition and Emotion, 28, 971–992.

Schweiger, S., Oeberst, A., & Cress, U. (2014). Confirmation bias in web-based search: A randomized online study on the effects of expert information and social tags on information search and evaluation. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16, e94. doi:10.2196/jmir.3044

Simeonsson, R. J., Scarborough, A. A., & Hebbeler, K. M. (2006). ICF and ICD codes provide a standard language of disability in young children. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 59, 365–373. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.09.009

Sinatra, G. M., Kienhues, D., & Hofer, B. K. (2014). Addressing challenges to public understanding of science: Epistemic cognition, motivated reasoning, and conceptual change. Educational Psychologist, 49, 123–138.

Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 50, 755–769. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00214.x

van Deemter, K. (2010). Not exactly: In praise of vagueness. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

White, R. W., & Horvitz, E. (2009). Cyberchondria: Studies of the escalation of medical concerns in web search. ACM Transactions on Information Systems, 27(4), 23.

World Health Organization. (1992). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, tenth revision (ICD-10). Geneva: World Health Organization.

World Health Organization. (2001). The international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). Geneva: World Health Organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kimmerle, J. et al. (2017). Motivated Processing of Health-Related Information in Online Environments. In: Buder, J., Hesse, F. (eds) Informational Environments . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64274-1_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64274-1_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-64273-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-64274-1

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)