Abstract

In the conclusion chapter, we summarize the book and present a practical guide for implementing customer engagement marketing, where the firm attempts to motivate, empower, and measure customer contribution to marketing functions beyond financial patronage. The chapter discusses how to use engagement tools and design engagement platforms to facilitate customer engagement, how to incentivize customer engagement, and how to capture value from customer engagement behaviors and the corresponding data generated from these behaviors. It examines both the targeting and timing decisions for deploying engagement marketing initiatives to maximize effectiveness over the entire customer journey. Throughout the chapter, we discuss potentially fruitful areas of future research that emerge from the perspectives presented in the book.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Over the past ten years, there has been a transformation in marketing theory and practice that we cannot begin to understand without acknowledging the changing role of the customer. Often at lower costs and greater effectiveness, customers are increasingly serving as pseudo-marketers, actively and voluntarily contributing to marketing functions, such as customer acquisition , expansion, and retention ; product innovation; and marketing communication. The chapters collected in this book present various perspectives on customer engagement and represent a compilation of current thought leadership in this domain. Importantly, each perspective contributes to our understanding of how to effectively execute customer engagement marketing initiatives in which the firm deliberately motivates, empowers, and measures customer contribution to marketing functions beyond their financial patronage (Harmeling et al. 2017a). In this final chapter, we summarize these perspectives to provide a practical guide for implementing customer engagement marketing as well as offer potentially fruitful areas of future research.

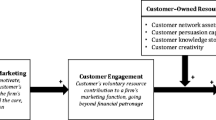

Customer engagement marketing actively enlists customers as pseudo-marketers for the firm. It is distinct from marketing strategies such as promotion marketing, which uses a special offer to raise a customer’s interest in and influence over focal product purchases versus competitor product purchases, and relationship marketing, which captures “marketing activities directed towards establishing, developing, and maintaining successful relational exchange” (Morgan and Hunt 1994, p. 22). The objective of engagement marketing is to encourage active customer contribution to the firm’s marketing functions, which differs from promotion marketing’s focus on inducing a single transaction with the focal firm and relationship marketing’s focus on motivating future repeat transactions with the customer. In addition, in promotion marketing the customer is merely a receiver of value through marketing actions and in relationship marketing the customer negotiates value received in that particular customer—firm relationship directly with the firm. However, with engagement marketing, the customer can exercise a high level of control over value creation and can affect outcomes that move beyond their particular customer-firm relationship to the broader customer population.

Probably the most essential point of differentiation from other marketing strategies, however, is the engagement marketing view of the customer. Both promotion and relationship marketing take more of an economic perspective, focusing on the customer’s current and future financial contributions. Engagement marketing, however, views the customer as possessing resources beyond their financial contribution that are desirable and otherwise unattainable to the firm. Accordingly, Harmeling et al. (2017a) identify four key customer-owned resources. First, customer network assets represent the number and diversity of a customer’s interpersonal ties within his or her social network, which benefit the firm by increasing the reach of marketing initiatives and providing access to otherwise inaccessible or particularly influential customer groups. Second, customer persuasion capital represents the “trust, goodwill, and influence a customer has with other existing or potential customers” (Harmeling et al. 2017a, p. 316–17) and can improve the authenticity and diagnosticity of customer engagement (e.g. word of mouth ) over other firm driven marketing actions. Third, customer knowledge stores capture a “customer’s accumulation of knowledge about the product, brand, firm, or other customers” (Harmeling et al. 2017a, p. 317) and can improve the quality and relevance of marketing initiatives, enhance product developments, and improve customer-to-customer interactions. Fourth, customer creativity captures the customer’s “production, conceptualization, or development of novel, useful ideas, processes, or solutions to problems” (Kozinets et al. 2008, p. 341) and provides unique insights beyond those available within the firm. Therefore, customer engagement marketing differs from other marketing strategies in its objective, creation of value, and, importantly, view of the customer.

Designing Customer Engagement Marketing Initiatives

The aspects of customer engagement marketing that make it distinct from promotion and relationship marketing suggest tactics that are effective in these other domains may not be effective for engaging customers, thereby requiring a new perspective. Several of the chapters in this book focused on antecedents of customer engagement and can inform the design of customer engagement marketing strategies. In Table 14.1, we summarize the implications to marketing practice as well as research directions emerging from this new perspective.

Facilitating Customer Engagement

Engagement marketing requires designing customer interactions outside of the core economic transaction in which customers will be both motivated and empowered to contribute to the firm beyond their financial patronage. Many engagement initiatives take the form of shared interactive experiences that are meant to stimulate voluntary customer contributions to marketing functions (Harmeling et al. 2017a). Vivek, Beatty, and Hazod (Chap. 2) suggest that providing an optimal balance between the customer’s ability and the challenge of the experience can improve the effectiveness of these initiatives. Yet, calibrating the engagement event may require dynamically adapting based on customer learning, which suggests personalization is also relevant in delivering the engagement initiative (Bleier, De Keyser, and Verleye, Chap. 4). Calder, Hollebeek, and Malthouse (Chap. 10) suggest that experiential initiatives may provide a means for brands to connect with customers in their attainment of higher life goals . Therefore, personalizing the initiative to the target customer’s current abilities as well as their broader life goals could potentially enhance the effectiveness of experiential engagement initiatives.

Part of the appeal of experiential engagement initiatives is that they offer unique, often one-time, experiences. However, because of this high perishability, Calder, Hollebeek, and Malthouse (Chap. 10) suggest poorly delivered initiatives can induce not only dissatisfaction and disappointment, but also a sense of lost opportunities and regret. Thus, calibrating the availability window such that it is brief enough to create a sense of novelty but extended enough to provide accessibility is key (Arnould and Price 1993; Vivek, Beatty, and Morgan 2012). Future research is needed in this domain.

Although the design of the engagement initiative is critical for motivating customers, just as critical is the firm’s ability to empower contribution in ways that make it impactful. Therefore, effective customer engagement requires investment in engagement tools that facilitate both customer-to-customer and customer-to-firm interactions. Harmeling et al. (2017a) identify four types of tools. First, amplification tools diffuse engagement behaviors among the participating customers’ existing network structures (e.g. share buttons). Second, connective tools link the participating customer to other customers, the firm, or the engagement initiative (e.g. tagging, following buttons). Third, feedback tools enable the customer to react to a particular action by the firm or other customers (e.g. comment boxes, likes). Fourth, creative tools facilitate the creation, development, and contribution of unique ideas (e.g. filtering and editing tools). Determining when and how to use these tools warrants future research.

Engagement tools are rarely used in isolation but rather contribute to the design of an overall platform (e.g. My Starbucks Ideas) or environment (e.g. brand communities) that enables customer-to-customer and customer-to-firm interactions (Schau et al. 2009). In taking this more holistic view, culture and norms become relevant to facilitating the self-disclosures that are inherent in customer engagement. Vivek, Beatty, and Hazod (Chap. 2) suggest that the customer’s perception of the authenticity of interactions and feelings of psychological safety are key to designing an effective environment for customer engagement. They further suggest that authenticity can be achieved through the acceptance of conflicting viewpoints (e.g. positive and negative reviews), whereas psychological safety develops when people believe others will not think less of them if they make a mistake, ask silly questions, or ask for help, information, or feedback. Future research should investigate the role of engagement tools in both enhancing customer engagement independently and holistically, to create effective engagement platforms (Kozinets et al. 2008; Nambisan 2002).

Incentivizing Customer Engagement

If engagement marketing shifts the role of the customer to that of a pseudo-marketer (i.e. pseudo-employee), then the firm must assume the role of pseudo-employer. From this perspective, motivating, recognizing, and rewarding customer work and productivity are essential for effective engagement marketing initiatives. In Chap. 6, Bijmolt and colleagues examine the possibility of augmenting traditional programmatic incentive structures (e.g. multi-tier loyalty programs) to motivate engagement behaviors. They suggest that effective incentivizing requires a balance between instrumental benefits, or those that enhance economic utility (e.g. money, prizes), symbolic benefits (e.g. status ), and emotional benefits (e.g. customer company identification). In addition, Vivek, Beatty, and Hazod (Chap. 2) suggest “people find an activity worthwhile when they feel they can make a difference and are not being taken for granted”. Thus, nontraditional incentives such as amplified voice, or the “amplification of a customer’s engagement efforts through the firm’s paid, earned, or owned channels”, may also be effective (Harmeling et al. 2017a, p. 331). Providing feedback on how customer contributions are used could be an additional incentive for customer engagement. It is possible, however, that the effectiveness of an incentive may depend on the nature of the requested engagement behavior. If the requested behavior requires a high degree of self-disclosure (e.g. product ideas, product uses), incentives that increase its visibility (e.g. amplified voice) may appear intrusive and potentially erode effectiveness. Future research is needed to examine optimal incentive structures to motivate each unique form of customer engagement (Ryu and Feick 2007). In addition, research on incentivized word of mouth suggests that knowledge of an instrumental reward can erode the perceived authenticity of the resulting recommendation (Verlegh et al. 2013). Research into how each of the benefits of the incentive affects other customers’ perceptions of the resulting customer engagement could be investigated.

Beyond the direct incentives, a person’s membership in a multi-tier incentive program (e.g. Starbuck’s Gold Member) can create feelings of being part of an exclusive group (Bijmolt et al. Chap. 6). Because group members often share similar experiences (e.g. earning and experiencing rewards ), this membership can enhance in-group feelings in which the customer may take actions to support and protect that group, therefore, perpetuating further customer engagement (Harmeling et al. 2017b). Future research should investigate the group aspects of certain engagement incentives (Schau et al. 2009). Building on this, a potentially fruitful area of research is to investigate the differences in future customer engagement between “earned group membership” and “given group membership”.

As a final note on incentivizing customer engagement, Bijmolt and colleagues (Chap. 6) present an interesting dynamic in which encouraging customer engagement (e.g. word of mouth ) about the incentive itself (especial symbolic rewards ) can enhance the incentive’s effects. However, caution must be employed when deploying this strategy in that symbolic rewards require a small, exclusive, elite group to be effective, which can trigger negative bystander effects among customers that are not part of that group if not carefully managed. Thus, visibility of the reward is a double-edged sword that could produce status effects for one customer but could also produce perceptions of unfairness or jealousy for others (Steinhoff and Palmatier 2014). Therefore, a key area of research is in calibrating effective rewards and incentives and how engagement (e.g. word of mouth ) about the reward or incentive can (positively or negatively) affect its effectiveness.

Capturing Value from Customer Engagement

Customer engagement behaviors (e.g. word of mouth , customer feedback) can directly benefit the firm by contributing to customer acquisition , product innovation, marketing communication, and other marketing functions. Yet several of the chapters in this book touch on indirect sources of value through data benefits that can enhance the product offering and improve strategic decision-making. Customer engagement inherently involves a degree of customization where the customer voluntarily discloses self-relevant information to actively adapt the marketing initiative to fit his or her preferences. Bleier, De Keyser, and Verleye (Chap. 4) suggest that customization and self-disclosure not only provide visibility to customer behaviors outside the core economic transaction but also create a more complete description of the customer’s preferences. The resulting “mass engagement data” then increases the breadth and speed of data collection, which facilitates learning (e.g. Nest Thermostat and Apple autocorrect) and aggregation of feedback to the customer that can improve the firm’s offering, both of which were previously not possible (e.g. “25 people liked you since you last checked Tinder”). Thus, engagement data provides the necessary resources for the firm to monitor, adapt, and personalize product offerings and general interactions with customers over the entire customer journey .

One of the major benefits of a customer engagement marketing strategy is the increased visibility of customer behaviors outside the core economic transaction, which can be particularly informative in assessing customer value (Kumar et al. 2010). Venkatesan, Petersen, and Gussoni (Chap. 3) suggest that assessing customers based on this additional engagement data can often provide a more accurate view of the value of a particular customer to the firm such that customers with low purchase frequencies or amounts may possess valuable resources such as extraordinary reach and influence to particularly valuable potential customers previously unaccounted for in traditional measures of customer value . This more holistic view can influence strategic decisions such as who to target or how to structure key account teams. With a traditional customer lifetime value perspective, teams are typically dedicated to the most profitable customers, but it may be more effective to allocate teams to the most vocal customer or most informative customers (Chap. 3). These structural and indirect benefits warrant future research.

Extracting the value from engagement data requires three major processes (data collection, data analysis, and strategic adaptation). As a first step, customer data must be collected and matched to customer profiles. This requirement reinforces the value of investments in engagement tools that capture behaviors outside the core economic transaction and loyalty programs that provide a means of linking those behaviors to the customers, which together creates the conditions necessary to extract value from these data. Once collected, however, the magnitude of potential data can create challenges in which data filtering becomes necessary before engagement data can be analyzed and incorporated into strategic decision-making (Smith 2014). Learning algorithms and systems that interactively audition and incorporate new data to adapt marketing mix elements in real time may be potentially useful (Chung et al. 2016), yet requires future research. Bleier, De Keyser, and Verleye (Chap. 4), however, caution that learning “too quickly” could be seen as invasive and potentially trigger defensive responses. Finally, the firm should provide transparency and control to customers on their data management policies to reap benefits from customer engagement data and not cause future feelings of violation (Martin et al. 2017). Future research should investigate effective strategies for collecting, filtering, and analyzing engagement data as well as consumer responses to such processes and potential privacy issues (Aguirre et al. 2016).

Deploying Customer Engagement Marketing Initiatives

Beyond designing the engagement initiative, marketers must determine who to target for engagement initiatives and when it is best to target them. When considering these two strategic decisions from a traditional perspective (e.g. promotion or relationship marketing), decision-making criteria is typically narrowly focused on economic factors (e.g. share of wallet or customer lifetime value ). The more holistic view of the customer embraced in engagement marketing suggests enhancements to these criteria.

Targeting Customers for Engagement Initiatives

The first key decision in deploying engagement initiatives involves targeting customers. The chapters in this book identify two perspectives on determining which customers are the most effective targets of customer engagement initiatives, customer value , and success likelihood. In engagement marketing, valuations go beyond the traditional economic-focused assessments to acknowledge and capture valuable customer-owned resources. Venkatesan, Petersen, and Gussoni (Chap. 3) present and evaluate three enhanced measures of customer value ; customer influence value , customer referral value , and customer knowledge value. For example, customer influencer value measures the size of the customer’s social network and therefore captures the customer’s network assets. Although these valuation criteria provide new insights, the authors suggest that, because of the rules of sameness, the traditional measure of customer lifetime value may still be a useful proxy for assessing the economic value of a customer’s network assets as an indicator of “rich friends”. Thus, a combination of or triangulation across measures may be more effective. Reinartz and Berkmann (Chap. 11) suggest using lead users as a proxy for identifying customers with high knowledge stores, whose needs will become general in the marketplace sometime in the future. Although a significant amount of work has been done in this area, determining which assessments of customer value are effective for different engagement objectives is a fruitful area of future research. For example, valuations based on customer knowledge stores may be more effective for enhancing product innovations, whereas valuations of customer network assets more beneficial for marketing communication.

As an alternative perspective, several chapters provide insights into a success rate perspective in which customers are chosen on their likelihood to engage rather than their potential resource value. Liu et al.’s (Chap. 12) work suggests that customers who are predisposed to incorporate brands into their self or process information from a brand perspective may be effective targets for an engagement initiative. Vivek, Beatty, Hazod (Chap. 2) suggest customers high in experience-, cognition-, sensation-, and novelty-seeking are likely candidates for customer engagement. In addition, a customer’s perceived psychological availability, or his or her level of physical, emotional, and cognitive resources available for the engagement marketing initiative, will influence his or her level of engagement. Finally, they suggest role readiness, or the customer’s willingness and ability to contribute, is a key predictor of engagement and can potentially be enhanced through encouragement, support, socialization, and training (e.g. how to engage videos). Venkatesan, Petersen, and Gussoni (Chap. 3) suggest a customer’s response rate to other marketing campaigns or their previous engagement behaviors (e.g. referral performance, number of previous suggestions, or comments) may also be significant predictors of future engagement behavior. Ultimately, a combination of value to firm and likelihood to engage may be the best means of identifying potential customers, which warrants future research.

Beyond targeting customers with engagement initiatives, Venkatesen, Petersen, and Gussoni (Chap. 3) suggest future research should assess the effectiveness of targeting customers with high persuasion capital and network assets (e.g. influencers) with cross-sell promotions on products that are not necessarily effective at stimulating purchases but rather more effective at generating customers engagement behaviors (e.g. word of mouth ) about the products. Similarly, different customer resources may be more or less appealing based on the product type. For example, complex products may benefit more from customer knowledge stores than other customer resources. In addition, the authors suggest that future research should investigate how targeting may differ when focusing on customer groups (e.g. sports teams, clubs) rather than individuals.

While the majority of research focuses on engaging consumers, Reinartz and Berkmann (Chap. 11) suggest more research is needed on how to effectively engage business customers. The multi-person buying process, need for customization , and narrowly rather than generally focused customer knowledge may make engagement among business customers challenging and potentially less valuable. In addition, high degrees of dependence and resource integration between firms will likely alter the effectiveness of engagement. The authors also acknowledge the distinction between individual (referrals) and organizational level engagement (co-development), which can have implications for the design and management of engagement initiatives. Future research should investigate these areas of differentiation as well as the unique influence of trust, commitment, and dependence in the B2B domain to assess how consumer-based engagement strategies might need to be adapted.

Beckers et al. (Chap. 7) offer an additional concern for engaging business customers such that there is a fundamental disconnect between the users of engagement platforms and decision-makers that has implications on both the participation and value of engagement efforts. For example, employee contribution to the engagement initiative (e.g. posts, responses to other participant posts, etc.) may not be valued by the employer and may actually simulate punishment if viewed as distracting to the employees core purpose to the employer. Thus, motivation, norms, and engagement processes in the B2B domain warrant future research.

Determining Timing of Engagement Initiatives and Exposure to Customer Engagement

The second key decision in deploying engagement initiatives is determining the timing of deployment. The contributing chapters examine this from both a functional perspective, in which engagement helps to inform other customers throughout the purchase decision process, and a relational perspective, in which engagement contributes to and is affected by the relational aspects of exchange (e.g. trust and commitment). Minnema et al. (Chap. 5) examine this question by investigating the role of engagement across the purchase cycle and how it impacts product returns. They suggest that exposure to customer engagement from other customers (i.e. product reviews) in the prepurchase stage can influence the effects of imperfect information on product returns and that this is especially true of online purchases. If there is not enough customer engagement, it could spark returns because of poor fit, but too much (or too positive of reviews) could increase expectations and also spark returns. Thus, this requires careful consideration of stimulating the appropriate amount of customer engagement among postpurchase customers. As Hochstein and Bolander (Chap. 9) recognize, exposure to customer engagement early in the buying process can alter the effectiveness of traditional elements of the selling process, suggesting that there has been a shift that requires salespeople to take on more of a knowledge broker role. Thus, research on properly calibrating when to expose customers to other customers’ engagement behaviors, when to stimulate customer engagement through direct requests, and how to respond to increased customer engagement throughout the purchase cycle is needed.

Participation in an engagement initiative requires a degree of self-disclosure that, if managed improperly, can spark negative responses among consumers. Consequently, Bleier, De Keyser, and Verleye (Chap. 4) suggest adapting engagement requests over the customer lifetime with more restrictive and less invasive requests early on, but, more general, autonomous requests later on as familiarity, knowledge, trust, and emotional attachment build. Research that investigates the influence of dynamic relational expectations on the effectiveness of customer engagement initiatives could provide insights into the strategic deployment of engagement initiatives (Harmeling et al. 2015). On the other hand, for B2B customers, Beckers et al. (Chap. 7) suggest customer engagement should be managed over the stages of value chain rather than the customer life cycle. The adaptations necessary in B2B exchanges and taking dynamic perspective are interesting avenues for future research.

Potential Dangers of Customer Engagement Marketing

Engagement marketing is intended to improve firm performance by either providing access to customer resources that were previously unattainable to the firm or shifting value generation from internal to external entities. Works by both Vivek, Beatty, Hazod (Chap. 2) and Bleier, De Keyser, and Verleye (Chap. 4) suggest, however, that engagement initiatives often require complex customization . Because of this, they need high levels of technical support and large investments of human capital. Firms should carefully assess the potential management and implementation costs of customer engagement initiatives versus the potential benefits. For instance, Minnema et al. (Chap. 5) suggest that high levels of engagement can increase customer’s overall expectations, often leading to increased dissatisfaction and potentially to product returns .

For engagement marketing to be successful, firms must empower customers; however, this relinquishing of control can create potential risks (Van Doorn et al. 2010). Engagement marketing initiatives are designed to extract value from customers and require investment in tools and platforms that amplify the consumer voice and impact on other current and potential consumers. This creates conditions where the value producer can become a value destroyer (Roehm and Brady 2007). For example, customers have turned engagement initiatives such as the McDonald’s hashtag #McDstories into “bashtags”, thus turning a firm supported channel into an avenue for brand terrorism and negative word of mouth . Future research should investigate both proactive and reactive means of managing these potential vulnerabilities.

The data collection aspect of customer engagement can create improved visibility of customer behaviors outside the core economic transaction. This increased visibility comes with increased responsibility for the firm. Customers are now more cognizant than ever before of data privacy issues. Thus, future research could explore how engagement data is captured, stored, used, and protected as well as what implications this has from a data privacy standpoint (Martinet al. 2017).

In summary, the radically transformed marketing environment in which customers can exert greater influence over marketing functions than ever before has offered a new avenue for strategic advantage over competitors (Kumar and Pansari 2016). There is now a need for engagement marketing research to understand the most effective ways for firms to motivate, empower, and measure customer contributions to marketing functions. The work presented in this edited book provides a foundation for examining this new perspective, yet much work remains to be done. Research areas include investigating the elements of the engagement initiative as well as engagement platforms that most effectively stimulate customer engagement, incentivizing customer engagement, targeting customers for participation in engagement initiatives, deploying customer engagement initiatives across the entire customer journey , and assessing the potential dark side of customer engagement marketing. This book and the collection of chapters within it should serve as a guide for academics advancing research in this domain and practitioners designing and implementing engagement marketing strategies.

References

Aguirre, E., Roggeveen, A. L., Grewal, D., & Wetzels, M. (2016). The Personalization–Privacy Paradox: Implications for New Media. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 33(2), 98–110.

Arnould, E. J., & Price, L. L. (1993). River Magic: Extraordinary Experience and the Extended Service Encounter. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(1), 24–45.

Bleier, A., & Eisenbeiss, M. (2015a). Personalized Online Advertising Effectiveness: The Interplay of What, When, and Where. Marketing Science, 34(5), 669–688.

Bleier, A., & Eisenbeiss, M. (2015b). The Importance of Trust for Personalized Online Advertising. Journal of Retailing, 91(3), 390–409.

Chung, T. S., Wedel, M., & Rust, R. T. (2016). Adaptive Personalization Using Social Networks. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44(1), 66–87.

Dholakia, U. M., Bagozzi, R. P., & Pearo, L. K. (2004). A Social Influence Model of Consumer Participation in Network-and Small-Group-Based Virtual Communities. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 21(3), 241–263.

Fuchs, C., Prandelli, E., & Schreier, M. (2010). The Psychological Effects of Empowerment Strategies on Consumers’ Product Demand. Journal of Marketing, 74(1), 65–79.

Harmeling, C. M., Palmatier, R. W., Houston, M. B., Arnold, M. J., & Samaha, S. A. (2015). Transformational Relationship Events. Journal of Marketing, 79(September), 39–62.

Harmeling, C. M., Moffett, J. W., Arnold, M. J., & Carlson, B. D. (2017a). Toward a Theory of Customer Engagement Marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(3), 312–335.

Harmeling, C. M., Palmatier, R. W., Fang, E., & Wang, D. (2017b). Group Marketing: Theory, Mechanisms, and Dynamics. Journal of Marketing, 81(July), 1–24.

Henderson, C. M., Beck, J. T., & Palmatier, R. W. (2011). Review of the Theoretical Underpinnings of Loyalty Programs. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 21(3), 256–276.

Henderson, C. M., Steinhoff, L., & Palmatier, R. W. (2014). Consequences of Customer Engagement: How Customer Engagement Alters the Effects of Habit-, Dependence-, and Relationship-Based Intrinsic Loyalty (Marketing Science Institute Working Papers Series).

Kozinets, R. V., Hemetsberger, A., & Schau, H. J. (2008). The Wisdom of Consumer Crowds: Collective Innovation in the Age of Networked Marketing. Journal of Macromarketing, 28(4), 339–354.

Kozinets, R. V., De Valck, K., Wojnicki, A. C., & Wilner, S. J. S. (2010). Networked Narratives: Understanding Word-of-Mouth Marketing in Online Communities. Journal of Marketing, 74(2), 71–89.

Kumar, V., & Pansari, A. (2016). Competitive Advantage Through Engagement. Journal of Marketing Research, 53(4), 497–514.

Kumar, V., George, M., & Pancras, J. (2008). Cross-Buying in Retailing: Drivers and Consequences. Journal of Retailing, 84(1), 15–27.

Kumar, V., Aksoy, L., Donkers, B., Venkatesan, R., Wiesel, T., & Tillmanns, S. (2010a). Undervalued or Overvalued Customers: Capturing Total Customer Engagement Value. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 297–310.

Kumar, V., Petersen, J. A., & Leone, R. P. (2010b). Driving Profitability by Encouraging Customer Referrals: Who, When, and How. Journal of Marketing, 74(5), 1–17.

Martin, K. D., & Murphy, P. E. (2017). The Role of Data Privacy in Marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(2), 135–155.

Martin, K. D., Borah, A., & Palmatier, R. W. (2017). Data Privacy: Effects on Customer and Firm Performance. Journal of Marketing, 81(1), 36–58.

Menguc, B., Auh, S., Yeniaras, V., & Katsikeas, C. S. (2017). The Role of Climate: Implications for Service Employee Engagement and Customer Service Performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(3), 428–451.

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38.

Nambisan, S. (2002). Designing Virtual Customer Environments for New Product Development: Toward a Theory. Academy of Management Review, 27(3), 392–413.

Pansari, A., & Kumar, V. (2017). Customer Engagement: The Construct, Antecedents, and Consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(3), 294–311.

Roehm, M. L., & Brady, M. K. (2007). Consumer Responses to Performance Failures by High-Equity Brands. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(4), 537–545.

Ryu, G., & Feick, L. (2007). A Penny for Your Thoughts: Referral Reward Programs and Referral Likelihood. Journal of Marketing, 71(1), 84–94.

Schau, H. J., Muñiz, A. M., Jr., & Arnould, E. J. (2009). How Brand Community Practices Create Value. Journal of Marketing, 73(5), 30–51.

Schmitt, P., Skiera, B., & Van den Bulte, C. (2011). Referral Programs and Customer Value. Journal of Marketing, 75(1), 46–59.

Smith, D. (2014). Tuning In and Turning On: Leveraging Customer Engagment Data for Maximum Return. Loyalty Management.

Steinhoff, L., & Palmatier, R. W. (2014). Understanding Loyalty Program Effectiveness: Managing Target and Bystander Effects. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44(1), 1–20.

Trusov, M., Bucklin, R. E., & Pauwels, K. (2009). Effects of Word-of-Mouth Versus Traditional Marketing: Findings from an Internet Social Networking Site. Journal of Marketing, 73(5), 90–102.

Van Doorn, J., Lemon, K. N., Mittal, V., Nass, S., Pick, D., Pirner, P., & Verhoef, P. C. (2010). Customer Engagement Behavior: Theoretical Foundations and Research Directions. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 253–266.

Verlegh, P. W. J., Ryu, G., Tuk, M. A., & Feick, L. (2013). Receiver Responses to Rewarded Referrals: The Motive Inferences Framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41(6), 669–682.

Vivek, S., Beatty, S., & Morgan, R. (2012). Customer Engagement: Exploring Customer Relationships Beyond Purchase. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 20(2), 122–146.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Harmeling, C.M., Moffett, J.W., Palmatier, R.W. (2018). Conclusion: Informing Customer Engagement Marketing and Future Research. In: Palmatier, R., Kumar, V., Harmeling, C. (eds) Customer Engagement Marketing. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61985-9_14

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61985-9_14

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-61984-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-61985-9

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)