Abstract

To make the case that gender inclusivity is a fundamental yet ignored aspect of the strategic leadership paradigm (SLP), I make four lines of argument. First, I outline the theoretical boundaries of the strategic leadership theory and demonstrate how inclusivity can significantly advance the boundaries of SLP. Second, I discuss the notion of gendered strategic leadership in which a gender orientation is incorporated into the underpinning theoretical architecture of inclusive SLP. This approach demonstrates how and why embedding gender inclusivity in SLP represents a meaningful way to advance our understanding of how leaders do strategy in today’s diverse world. Third, I discuss the merits of gender inclusive SLP and briefly explain pitfalls of studying strategic leadership not using this paradigm. Finally, I elaborate on the implications of the study, illuminate several research directions in this paradigm and argue the importance of having an open mind toward research methods when a gender inclusive paradigm is adopted.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

How do business leaders 1 matter? Early studies showed that leaders matter because they make decisions which determine the fate of their firms (Miller et al. 1982; Child 1972; Prahalad and Bettis 1986; Hamel and Prahalad 1992). Recent advances transcend these limited strategic foci by suggesting that leaders matter because they are stewards of the entire enterprise, its structure , culture and identity (Hambrick and Quigley 2013; Montgomery 2008; Quigley and Hambrick 2015). Advocates of the latter school believe that fundamental function of a leader is to design the organization and define what it is and how it adjusts itself to achieve its goals (Finkelstein et al. 2009; Montgomery 2008; Simsek et al. 2015).

Not only is the current workforce becoming more diverse but also the global business landscape is going through an unprecedented metamorphosis driven by global openness, rapid blending of cultures and recent socio-cultural changes (Deloitte 2012; Hollander 2012; Nembhard and Edmondson 2006; Wuffli 2016). These circumstances require leaders to be inclusive, to include skills, opinions and values of employees regardless of their gender and backgrounds (Carmeli et al. 2010; Hirak et al. 2012; Mitchell et al. 2015; Sugiyama et al. 2016; Wuffli 2016). There is a pressing need to explicitly incorporate the notion of inclusivity into the underlying theoretical foundation of leadership (Carmeli et al. 2010; Sugiyama et al. 2016). As Wuffli (2016, p. 3) argues:

an inclusive leadership approach is called for where both the what (knowing what are “the right things”) and the how (doing the “things right”), as well as a high degree of agility to constantly adjust to changing environments, are instrumental for achieving success.

Considering this trend, one may ask the following question: to what extent does the current paradigm of strategic leadership address inclusivity? The answer is dismal. An overview of the literature on strategic leadership reveals a vexing lack of attention to the concept of inclusivity and leaders’ inclusiveness . This void is surprising because although the notion of diversity in leadership has long been discussed (Knight et al. 1999; Li et al. 2016; Qin et al. 2013; Rogelberg and Rumery 1996; Simons et al. 1999), inclusivity as a closely related notion has received very little attention from the strategic leadership scholars. This gap prompts us to revisit the current paradigm of strategic leadership from an inclusive view.

The objective of this chapter is to bring inclusivity to the forefront of strategic leadership. This focus portrays diversity as an asset rather than a liability and uses inclusivity as a strategic way to capitalize on this asset. To this end, first an overview of the concept of inclusivity and a leader’s inclusiveness is offered. Then I augment the literature on inclusive leadership and strategic leadership and outline an inclusive paradigm for strategic leadership. Inclusivity covers all aspects of diversity from gender to age , ethnicity and nationality (Hambrick 2007; Hambrick and Mason 1984). For the sake of brevity, I narrow the focus on gender and point to some of the theoretical, practical and educational implications of a gendered approach to inclusive strategic leadership. The chapter concludes with a set of directions for future research on gender inclusiveness in strategic leadership.

Inclusivity, Inclusive Leadership and Leader’s Inclusiveness

Inclusivity and Inclusiveness

The Oxford Dictionary defines “inclusivity” as “an intention or policy of including people who might otherwise be excluded or marginalized , such as those who are handicapped or learning-disabled, or racial and sexual minorities .” It is an intentional act which expresses “the need to proactively ensure the participation of poor, underprivileged people in development processes.” Inclusivity means something that “covers or includes everything” or “is not limited to certain people” (Wuffli 2016, p. 2). Building on this understanding, business scholars have conceptualized inclusivity as an organizational characteristic in which employees from different backgrounds, those who are usually overlooked or marginalized, are included in organizational activities, decision-making and goal-setting processes.

Two points are noteworthy here. First, when an organization practices inclusivity, its employees regardless of their backgrounds feel accepted and treated as insiders (Shore et al. 2010). This enables an organization to benefit from a wider spectrum of skills and knowledge blended together in a coherent way. Second, since each employee brings a unique set of knowledge and skills to the organization, shaped and formed by their life trajectories , the practice of inclusivity enables an organization to help employees realize their unique potential and contribution to the organization.

Shore et al. (2010) used the optimal distinctiveness theory of Brewer (1991) to explain and integrate these two in a unified model of organizational inclusivity . According to Brewer (1991; p. 477), individuals’ collective identity is shaped by a tension between two needs: the need for “validation and similarity to others (on the one hand) and a countervailing need for uniqueness and individuation (on the other).” To be inclusive, an organization’s culture needs to satisfy employees’ needs for belongingness and uniqueness . Because these two “work together to create feelings of inclusion ” (Shore et al. 2010, p. 1266), organizational inclusivity is essentially different from diversity. It is a fundamental aspect of an organization’s culture in which employees’ needs for belongingness and uniqueness are cultivated and nurtured. An organization’s culture is a cornerstone of its strategy which is designed and reinforced by its strategic leaders. An organization’s inclusiveness is a function of its leaders’ inclusiveness.

Inclusive Leadership and a Leader’s Degree of Inclusiveness

Inclusive leadership is an elusive and multifaceted concept forged at the intersection of leadership and inclusivity as a diversity management approach in order to meet the challenges of increasing diversity in today’s work environments (Rayner 2009). It has been defined as “words and deeds exhibited by leaders that invite and appreciate others’ contributions” (Nembhard and Edmondson 2006, p. 941) and argued to be essentially about relationships aimed at accomplishing things for mutual benefit by “doing things with people, rather than to people,” which is the essence of inclusion (Hollander 2012, p. 3).

Followers can be included or excluded by the ways in which they are given access to goods, rights and responsibilities (Hollander 2012; Ryan 2014). In this sense, an inclusive approach to leadership overturns traditional leader-centered conceptions of leadership in which followers’ race, class, gender, and relationships can keep them from reaching their full potential (Ryan 2014) and encourages a more follower-centric style of leadership in which “leaders usually do have greater initiative, but followers are vital to success, and they too can become leaders” (Hollander 2012, p. 3). The bottom line here as stressed by Ryan (2014, p. 364) is that “leadership can never be truly inclusive unless the ends for which it is organized are also inclusive.” Followers, or employees in the case of organizational leadership, feel they are included when they experience both belongingness and value in the uniqueness of their identities (Shore et al. 2011).

To cultivate an environment where followers’ needs for belongingness and uniqueness are satisfied, organizations should reduce hierarchies associated with bureaucracy , conformity and power and position-seeking motives (Deloitte 2012; Wuffli 2016). An inclusive leadership fosters “equitable , hierarchical , (i.e. flattened) and horizontal relationships that transcend race, class, and gender divisions and hierarchies” (Ryan 2014, p. 364) of followers (employees) promoted in traditional organizational structures associated with exclusive, charismatic and power-seeking leaders (Sugiyama et al. 2016). To create horizontal and mutually beneficial relationships, leaders must develop informal networks with individuals by making themselves visible, accessible and available. With regard to inclusive leaders in educational organizations, Ryan (2014, p. 367) suggests leaders “have to present themselves in ways that will prompt others to want to engage in dialogue with them and to get others to trust, respect, appreciate, and like them.” These features imply an inclusive approach to leadership that is not only dynamic and bridge-building across different levels of organization (i.e. heterarchichal and unranked instead of hierarchical and ranked) but is explicitly normative in terms of encouraging leaders to reflect on, and take positions related to, their underlying ethics and virtues (Wuffli 2016). Nembhard and Edmondson (2006) argue that such a normative approach helps a wide variety of organizations overcome the inhibiting effects of status differences and improve cohesiveness and effectiveness of their teams and divisions. Taken together, I define inclusive leadership as follows:

A normative follower-centric approach to organizational leadership which places the main emphasis on the heterarchichal (i.e. unranked) relationships between leaders and their followers and availability and accessibility of leaders in order to enable followers to satisfy their needs to belongingness and uniqueness.

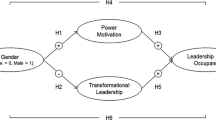

Informed by this definition, I argue that inclusiveness is a continuum. At one end, inclusive leaders who are follower-centric, available, accessible and capable of promoting heterarchies where followers can more easily satisfy their needs for belongingness and uniqueness are placed (Nembhard and Edmondson 2006; Wuffli 2016) and, at the other end, we have exclusive leaders who are power-seeking and self-centered (Ryan 2014). These leaders promote hierarchies, distance themselves from employees (i.e. become inaccessible) and cause employees to feel marginalized, isolated and fail to satisfy their needs for belongings and uniqueness (Fig. 9.1).

Equipped with this understanding, we can conceptualize an inclusive model of strategic leadership. The first step in this direction is to explore the extent to which the existing view of strategic leadership has incorporated the notion of a leader’s inclusiveness into its underlying logic.

Strategic Leadership: Exclusive or Inclusive

From Strategy to Leadership

According to Nag et al. (2007, p. 942), strategy “deals with the major intended and emergent initiatives taken by general managers on behalf of owners, involving utilization of resources, to enhance the performance of firms in their external environments.” This definition implies strategy is the responsibility of top managers in the organization (Hambrick and Fredrickson 2001). More precisely, strategy “rests on the assumption that the thoughts, feelings, and social relations of general managers influence the activities and performance of firms” (Powell 2011, p. 1485). Not every general manager is a strategic leader. A common distinction between managers and leaders is that “managers are people who do things right, while leaders are people who do the right thing” (Wuffli 2016, p. 3). Based on this thinking, leaders sit at the top of an organization and know what the “right things ” are, whereas the managers below need not worry and challenge these things but rather should just focus on “doing them right .” This is an example of heroic leadership , which should be critiqued because of its hierarchical and exclusive propensities . Strategy literature takes a very similar position and defines the boundaries of strategic leadership as “focussing on the people who have overall responsibility for an organization – the characteristics of those people, what they do, and how they do it.” (Hambrick 1989, p. 6).

Given this background, it is useful to think of strategic leadership as a scientific field of inquiry which fuses the theory and practice of leadership with the theory and practice of strategy to create a coherent body of knowledge about how organizations can be led strategically.

Strategic Leadership: A Paradigmatic View

At the outset, the field of strategic leadership advances our understanding of leadership in the strategic context (Hambrick 2007; Simsek et al. 2015). Because a theory is a set of statements which advance our understanding of a phenomenon (Christensen and Carlile 2009, p. 240), strategic leadership, in its broadest sense, can be portrayed as a grand theory (Hambrick 2007; Hambrick and Mason 1984).

Although logically correct, visualizing strategic leadership as a theory is incomplete and misleading because strategic leadership has a more important function than just advancing our understanding of leaders in the strategic context. It explains who strategic leaders are and what they do. Strategic leadership, in this respect, shapes our view of leadership and informs our understanding of how and when leaders can make strategic difference. In the language of Kuhn (1962, p. 175), it can be viewed as a paradigm. A paradigm is a cognitive framework composed of “an entire constellation of beliefs, values, and techniques and so on, shared by a given [scientific] community.” Paradigms perform two fundamental functions. First, they are informative like theories. Second, they are generative because they “create.....models from which spring particular coherent traditions of scientific research.” (Kuhn 1962, p. 10). Now, let us have a look at the field of strategic leadership through a paradigmatic lens and see if it has informed our understanding of inclusive strategic leaders.

Origins and Evolution of Strategic Leadership as an Exclusive Paradigm

The field of strategic leadership was developed by Hambrick and Mason (1984) based on the works of Cyert and March (1963) and Cyert et al. (1959). The main motivation behind this attempt was the absence of a clear role for leaders in the strategy literature. In fact, prior to the work of Hambrick and Mason (1984) strategy was determined by the environment based on imperfect assumptions of neo-classical economics in which leaders had minimal role to affect their organizations and their strategies (Cyert and Williams 1993). Following changes in the theory of the firm (Cyert and March 1963) and revisiting the nature of strategy as a managerial job (Child 1972), Hambrick and Mason (1984) proposed the model of strategic leadership suggesting that an organization’s behavior (i.e. being and becoming) is the reflection of the behavior of its leaders.

Strategic leadership makes three fundamental propositions: (1) strategic leaders have the power and authority to shape and affect the strategic posture of their organizations; (2) leaders’ demographics including age, personality, gender, education level, nationality, experience and cognitive skills determine how they perceive their business environment, attend to strategic issues and make choices which affect the being and becoming of their organizations; and (3) leaders work in teams. Hence, team-based behaviors, interactions and team composition (i.e. diversity) affect leaders’ decision-making processes and their organizations’ behaviors (Hambrick 2007; Hambrick and Mason 1984). Strategic leadership satisfies the criteria of a paradigm as identified by Kuhn (1962). It shapes our view and perception of the role of top managers and generates fruitful research streams along at least three directions:

-

1.

Types of diversity in top teams and their organizational performance . This includes gender diversity (Baixauli-Soler et al. 2015; Perryman et al. 2016); nationality diversity (Nielsen and Nielsen 2012; Ruigrok et al. 2007); and education, age, as well as functional and general experience (Knight et al. 1999; S. Nielsen 2010; Talke et al. 2010).

-

2.

Psychology, cognition, personality and makeup of executives in top teams. This includes diverse factors such as hubris (Tang et al. 2015), ideology (Briscoe et al. 2014) and personality types (Peterson et al. 2003).

-

3.

Drivers as well as consequences of various team mechanisms inside top management teams such as team behavioral integration (Lubatkin et al. 2006), cohesion and conflict management (Mello and Delise 2015), advice seeking mechanisms (Alexiev et al. 2010), and relational decision-making (Goll and Rasheed 2005).

In the next section, I outline the boundaries of an inclusive paradigm for strategic leadership. My primary motivation is to make visible how the strategic leadership paradigm (SLP) fails to provide an explicit account of how strategic leaders, alone and in teams, make themselves available and accessible to employees, nurture inclusive heterarchichal relationships with employees, and cultivate an organizational atmosphere conducive to helping employees satisfy their needs for belongingness and uniqueness.

Moving Toward an Inclusive Paradigm for Strategic Leadership

As noted, strategic leadership informs our understanding of leadership in the strategic context and offers a unique window to study being and becoming of organizations from the perspective of their leaders. However, this traditional view is not inclusive. To address this deficiency , we need to change the way diversity is incorporated into the theoretical body of strategic leadership.

An inclusive view to the strategic leadership differs from the traditional view in its underlying assumptions about: (1) the general view of strategic leadership, (2) focus on inter- and intra-team differences, (3) unit of study, (4) view of diversity, (5) implications of diversity, (6) management of diversity and (7) scope of diversity. Table 9.1 compares these assumptions in the traditional and an inclusive view of strategic leadership.

In this way, inclusive strategic leadership replaces the notion of diversity with inclusiveness, aspires to predict how inclusive leaders differ from exclusive ones and redefines the domain of traditional strategic leadership by showing that strategic leadership is, in fact, about leaders’ inclusiveness and creating inclusive organizations where all employees feel included in key strategic actions and decisions. Figure 9.2 offers a schematic illustration of the change in the domain of strategic leadership from the traditional to the inclusive one.

As noted, the most fundamental change is pertinent to the general approach to leadership. In the traditional view of strategic leadership, executives and top management team are the central focus of attention. Their power, political skills, demographic attributes and key characteristics define how organizations behave. Thus, followers or employees are marginalized and ignored. An inclusive approach to strategic leadership changes this assumption. It suggests that strategic leaders matter if they adopt a follower-centric approach to their leadership. After all, there is no leader without a follower and any follower needs a leader. Therefore, a follower-centric approach to strategic leadership not only enables employers as followers to become more involved in organizational actions but also helps leaders tap into a wider set of skills and knowledge when making and implementing strategic choices .

In addition, an inclusive approach to strategic leadership shifts the focus from diversity to inclusion in top management and other organization teams across levels and departments. An inclusive approach to managing inter- and intra-team differences has proved very efficient in enhancing team management and improving various team processes (Hirak et al. 2012; Mitchell et al. 2015; Nembhard and Edmondson 2006), suggesting that teams’ inclusiveness rather than diversity could be a better unit of study. Furthermore, inclusive teams are diverse but view their diversity as an asset rather than a liability (Mitchell et al. 2015). Benefits emerging from belongingness and uniqueness such as psychological safety , engagement in quality improvement processes and learning (Hirak et al. 2012) make inclusive teams more effective than team which are simply diverse but with an exclusive mentality.

Finally, an exclusive approach to diversity where diversity is a complex liability leads to increased tension, conflict and other negative outcomes if not properly managed (Mitchell et al. 2015). However, an inclusive view of strategic leadership implies that negative outcomes of diversity can be mitigated via positive relationships which reinforce uniqueness and belongingness and value differences among members (Nembhard and Edmondson 2006). This creates a two-way operation of leadership and followership across all teams at different levels which generates respect, recognition, responsiveness and responsibility (Hollander 2012). Such an atmosphere promotes fairness of input and output to all and nurtures both competition and cooperation in an organization (Hollander 2012). It broadens the scope of diversity from top management teams to the entire organization covering top teams, boards of directors and all other teams across divisions , departments and the entire organization.

Taken together, if we consider early views of leadership in strategy as industry-centric focusing on the similarity of leaders followed by the emergence of strategy leadership as a leader-centric approach where attributes of leaders started to surface, then an inclusive approach to strategic leadership can be regarded as the third phase in the evolution of the SLP in which leadership is inclusive and follower-centric. Figure 9.3 illustrates these phases.

Having defined the importance of an inclusive approach to strategic leadership and its position in the evolution of SLP, I narrow the focus of discussion on gender inclusiveness as one of the most active fronts of research on diversity in the SLP.

Advancing an Inclusive View of SLP: The Importance of Gender Inclusivity

As noted, inclusivity is about managing people in such a way that differences among individuals become sources of untapped skills, knowledge and expertise, and traditionally marginalized individuals find a way to more easily and quickly satisfy their needs for belongingness and uniqueness. Employees’ gender is the most important source of difference among individuals and has been a topic of ongoing debate in the literature on organizational diversity (Bernardi et al. 2002; Campbell and Mínguez-Vera 2008; Cumming et al. 2016; Dwyer et al. 2003; Rogelberg and Rumery 1996; Sila et al. 2016). Despite the magnitude of research on the gender diversity in the mainstream research on organizational demographics, strategic leadership has only recently begun to explicitly address the issue of gender diversity at strategy levels. Yet research in this domain seems to be more active than in other aspects of diversity such as nationality and ethnicity (Nielsen and Nielsen 2013). Inspired by this trend, gender diversity can be regarded as an empirical front end for advancing theory and research in inclusive strategic leadership.

The research on the relationship between gender and leadership has been recently boosted by the realization that worldwide women are underrepresented in leadership roles and strategic leadership has been traditionally about men and their masculine features yet there is no conclusive evidence suggesting that women can’t lead as effectively and efficiently as men. In fact, Rosener (1990, p. 119) argues that, “women managers are succeeding today, but they are not adopting the command-and-control style of leadership traditionally practiced by men. Instead, they are drawing on the skills and attitudes they have developed from their experience as women.” A recent meta-analysis of research on women leadership by Hoobler et al. (2016) suggests that

commonly used methods of testing the business case for women leaders may limit our ability as scholars to understand the value that women bring to leadership positions

This observation aligns with the key point of this research that the traditional view of gender diversity in strategic leadership in which inclusivity is ignored may be misleading and offers an incomplete picture of the facets of gender diversity in strategy literature. An overview of recent research on gender diversity in strategic leadership (Table 9.2) further substantiates this observation.

The summary of this literature points to two key themes. First, even though the number of women in middle management has grown rapidly in the last two decades, the number of female CEOs in large corporations remains extremely low (Quintana-García and Benavides-Velasco 2016). According to Oakley (2000), this disproportionate diversity has been caused by (1) lack of line experience, (2) inadequate career opportunities, (3) gender differences in linguistic styles and socialization , (4) gender-based stereotypes , the old boy network at the top, and tokenism , (5) differences between female leadership styles and the type of masculine leadership style expected at the top of organizations and (6) the possibility that the most talented women in business often avoid corporate life in favor of entrepreneurial careers .

Thus, even though various studies point to positive impacts of having more women on TMTs on firms’ performance, creativity and even security and public perception, business organizations cannot hold on to their best and brightest women and still fail to fully capitalize on the benefits of having women in strategic leadership positions. Secondly, the strategic leadership literature still lacks a general understanding of the benefits of gender inclusivity and fails to offer a clear explanation for how gender inclusivity can be achieved.

Adopting a gender inclusive view of strategic leadership seems beneficial and timely. There is still a long way ahead to achieve a satisfactory level of understanding on how large and small companies can maximize their gains from a gender-inclusive approach to their leadership. It is obvious many obstacles still exist before true gender equity is achieved and inclusivity is a potential way toward this end. There is a chasm between gender diversity and gender inclusiveness. Bridging this chasm requires firms to adopt an inclusive approach to their strategic leadership. Such an approach could: (1) help the employees from different genders with managerial and leadership potentials in a follower-centric culture to realize their full potential, (2) reduce hierarchical obstacles faced by women who have the potential to rise to top managerial positions, (3) create an environment where women can satisfy their needs for belonging and uniqueness and (4) make leaders more accessible and available to employees who may feel isolated, marginalized and excluded. Hence, helping them share their skills, knowledge, opinions and expertise in a more open, mutually beneficial fashion and respectful manner.

Proposing a Research Agenda for Inclusiveness (Gender) in Strategic Leadership

As noted, an inclusive approach to strategic leadership represents a new paradigmatic phase. Hence, it is expected to generate multiple research streams. In this section, I propose few of these streams to stimulate systematic research in this domain.

First, as field of inquiry inclusivity in strategic leadership is in its formative phase. According to Edmondson and Mcmanus (2007), when a scientific field is in its formative stage, an open-ended inquiry about a phenomenon of interest using qualitative data that need to be interpreted for meaning from an exploratory view provides the best methodological fit. In keeping with this, research on inclusivity in strategic literature benefits immensely from qualitative exploratory case studies (Eisenhardt 1989; Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007) which are designed and conducted to generate context-specific and empirically rich insights into multiple facets of inclusivity by answering important yet unanswered questions such as (1) How do inclusive leaders nurture a follower-centric approach to leadership? (2) How do leaders generate cultures conducive to belongingness and uniqueness? (3) How do inclusive leaders make themselves available and accessible to employees and (4) How inclusive leaders remove positional and hierarchical barriers faced by traditionally marginalized employees such as women and ethnic minorities?

Another fruitful direction for research on an inclusive approach to strategic leadership pertains to the extensions which can be done to the existing strategic leadership literature. As noted, leaders’ level of inclusiveness has been found to be a powerful predictor of various team level factors such as team’s effectiveness, improvement efforts, members’ psychological safety (Nembhard and Edmondson 2006), team’s perception of identity and perceived status (Mitchell et al. 2015), as well as learning from failures (Hirak et al. 2012). Building on these findings, researchers interested in an inclusive approach to strategic leadership can examine how CEO’s level of inclusiveness affect various team’s mechanisms such as behavioral integration (Evans and Butler 2011), decision-making processes (Olie et al. 2012), conflict management (Olson et al. 2007) and advise seeking behavior (Alexiev et al. 2010). Furthermore, future research can examine how diversity in the inclusiveness of members of top management teams affects their teams and organizations. The scale proposed by Nembhard and Edmondson (2006) to measure leader’s inclusiveness helps researchers design generalizable large scale studied in these directions. In the same vein, CEOs’ inclusiveness can be studied in the context of gender diversity to assess and investigate how gender inclusive teams differ from other teams and what implications gender inclusivity not simple diversity has on leadership teams and firms.

Finally, it is to be noted that directions proposed here are only suggestive and by no means exhaustive. In fact, as Rayner (2009) argues, an inclusive approach to traditionally exclusive subjects such as strategic leadership is by nature emancipatory which enables researchers to use multiple methods, approaches and techniques in the design and conduct of their research. I encourage researchers to adopt an open mind and use creative imaginations and various methods from different angles to enrich the body of knowledge on inclusivity in strategic leadership in general and gender inclusiveness in strategic leadership in particular.

Implications

It is well understood that “understanding of effective leadership is itself in flux” (Sugiyama et al. 2016, p. 254). In line with this realization, the discussion presented in this chapter has an important implication for theoretical research on the SLP. The traditional view of strategic leadership is an incomplete theoretical field because despite the centrality of diversity in its underlying theoretical logic, it overlooks the importance of inclusiveness as a fundamental approach to promote and manage diversity in both top management teams and the entire organization. This echoes the point raised by Deloitte’s (2012) which suggests that global trends “point to inclusion as the new paradigm, and the inclusive leader as someone who seeks out diverse perspectives to ensure that insights are profound and decisions robust” (p. 1). By emphasizing inclusivity as a fundamental facet of strategic leadership, this chapter advances the understanding of strategic leadership by revisiting the traditional and exclusive view of strategic leadership. An inclusive SLP can address more questions and illuminate more sides of how, why and when strategic leaders matter in building and nurturing competitive organizations by capitalizing on the power of everyone, regardless of their backgrounds (Rosener 1990).

Concluding Remarks

In this chapter, I endeavored to develop an extended view of strategic leadership which brings inclusivity in general and gender equality in particular, to the forefront of strategy research. I argued that the traditional model of strategic leadership represents a paradigm that overlooks the significance of inclusivity and inclusiveness. Hence, some adjustments to this paradigm seem timely and required to fill this void. The outcome of this approach was a revisited paradigm for strategic leadership that directs scholarly understanding, actions and research toward a more inclusive direction in which executives consciously embrace and capitalize on the power of inclusivity both inside their teams and their organizations. This chapter is not a definitive agenda neither should it be considered a comprehensive guideline for studying inclusive strategic leadership. I believe, though, it makes an early contribution to this line of research by being among the first studies which explicitly point to the need for a more advanced view of how and why strategic leaders matter in building inclusive organizations and societies. I hope that I have set the stage for an ambitious research agenda for reframing the role of inclusivity thinking in the SLP. Hence, I would encourage future researchers and practitioners to critique and expand arguments offered in this chapter in order to unlock the mysteries of an increasingly important, but complex, set of relationships between leaders, the composition of top teams and makeup of organizations.

Notes

-

1.

Business leaders are loosely defined here as top managers, executives or strategic leaders who are in charge of the business

References

Alexiev, A. S., Jansen, J. J. P., Van den Bosch, F. A. J., & Volberda, H. W. (2010). Top management team advice seeking and exploratory innovation: The moderating role of TMT heterogeneity. Journal of Management Studies, 47(7), 1343–1364.

Baixauli-Soler, J. S., Belda-Ruiz, M., & Sanchez-Marin, G. (2015). Executive stock options, gender diversity in the top management team, and firm risk taking. Journal of Business Research, 68(2), 451–463. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.06.003.

Bernardi, R. A., Bean, D. F., & Weippert, K. M. (2002). Signaling gender diversity through annual report pictures: A research note on image management. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 15(4), 609–616.

Brewer, M. B. (1991). The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17, 475–482.

Briscoe, F., Chin, M. K., & Hambrick, D. C. (2014). CEO ideology as an element of the corporate opportunity structure for social activists. Academy of Management Journal, 57(6), 1786–1809.

Campbell, K., & Mínguez-Vera, A. (2008). Gender diversity in the boardroom and firm financial performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 83(3), 435–451.

Carmeli, A., Roni, R.-P., & Ziv, E. (2010). Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in creative tasks in the workplace: The mediating role of psychological safety. University of Nebraska, Psychology Faculty Publications. Paper # 43. http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/psychfacpub/43

Child, J. (1972). Organizational structure, environment and performance: The role of strategic choice. Sociology, 6(1), 1–22.

Christensen, C. M., & Carlile, P. R. (2009). Course research: Using the case method to build and teach management theory. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 8(2), 240–251.

Cumming, D., Leung, T. Y., & Rui, O. (2016). Gender diversity and securities fraud. Academy of Management Journal, 58(5), 1572–1593.

Cyert, R. M., & March, J. G. (1963). A behavioral theory of the firm. Englewood: Prentice-Hall.

Cyert, R. M., & Williams, J. R. (1993). Organizations, decision making and strategy: Overview and comment. Strategic Management Journal, 14(1), 5–10.

Cyert, R. M., Feigenbaum, E. A., & March, J. G. (1959). Models in a behavioral theory of the firm. Behavioral Science, 4(2), 81–95.

Deloitte. (2012). Inclusive leadership: Will a hug do? Sydney: Deloitte Australia.

Dwyer, S., Richard, O. C., & Chadwick, K. (2003). Gender diversity in management and firm performance: The influence of growth orientation and organizational culture. Journal of Business Research, 56(12), 1009–1019.

Edmondson, A. C., & Mcmanus, S. E. (2007). Methodological fit in management field research. Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1155–1179.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25.

Evans, R. W., & Butler, F. C. (2011). An upper echelons view of “Good to Great”: Principles for behavioral integration in the top management team. Journal of Leadership Studies, 5(2), 89–97.

Finkelstein, S., Hambrick, D. C., & Cannella, A. A. (2009). Strategic leadership: Theory and research on executives, top management teams, and boards. New York: Oxford University Press.

Francoeur, C., Labelle, R., & Sinclair-Desgagné, B. (2008). Gender diversity in corporate governance and top management. Journal of Business Ethics, 81(1), 83–95.

Goll, I., & Rasheed, A. A. (2005). The relationships between top management demographic characteristics, rational decision making, environmental munificence, and firm performance. Organization Studies, 26(7), 999–1023.

Hambrick, D. C. (1989). Guest editor’s introduction: Putting top managers back in the strategy picture. Strategic Management Journal, 10(1), 5–15.

Hambrick, D. C. (2007). Upper echelons theory: An update. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 334–343.

Hambrick, D. C., & Fredrickson, J. W. (2001). Are you sure you have a strategy? The Academy of Management Executive, 15(4), 48–59.

Hambrick, D. C., & Mason, P. A. (1984). Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. The Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 193–206.

Hambrick, D. C., & Quigley, T. J. (2013). Toward more accurate contextualization of the CEO effect on firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 35(4), 473–491.

Hamel, G., & Prahalad, C. K. (1992). Strategy as stretch and leverage. Harvard Business Review, 71(2), 75–84.

Hirak, R., Peng, A. C., Carmeli, A., & Schaubroeck, J. M. (2012). Linking leader inclusiveness to work unit performance: The importance of psychological safety and learning from failures. The Leadership Quarterly, 23, 107–117.

Hollander, E. (2012). Inclusive leadership: The essential leader-follower relationship. New York: Routledge.

Hoobler, J. M., Masterson, C. R., Nkomo, S. M., & Michel, E. J. (2016). The business case for women leaders: Meta-analysis, research critique, and path forward. Journal of Management. doi:10.5703/1288284316077.

Knight, D., Pearce, C. L., Smith, K. G., Olian, J. D., Sims, H. P., Smith, K. A., & Flood, P. (1999). Top management team diversity, group process, and strategic consensus. Strategic Management Journal, 20(5), 445–465.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions (1st ed.). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Li, J., Zhao, F., Chen, S., Jiang, W., Liu, T., & Shi, S. (2016). Gender diversity on boards and firms’ environmental policy. Business Strategy and the Environment, 26(3), 306–315.

Lubatkin, M. H., Simsek, Z., Ling, Y., & Veiga, J. F. (2006). Ambidexterity and performance in small- to medium-sized firms: The pivotal role of top management team behavioural integration. Journal of Management, 32(5), 646–672.

Mello, A. L., & Delise, L. A. (2015). Cognitive diversity to team outcomes: The roles of cohesion and conflict management. Small Group Research, 46(2), 204–226.

Miller, D., Kets De Vries, M. F. R., & Toulouse, J.-M. (1982). Top executive locus of control and its relationship to strategy-making, structure, and environment. Academy of Management Journal, 25(2), 237–253.

Mitchell, R., Boyle, B., Parker, V., Giles, M., Chiang, V., & Joyce, P. (2015). Managing inclusiveness and diversity in teams: How leader inclusiveness affects performance through status and team identity. Human Resource Management, 54(2), 217–239.

Montgomery, C. A. (2008). Putting leadership back into strategy. Harvard Business Review, 86(1), 54–60.

Nag, R., Hambrick, D. C., & Chen, M. J. (2007). What is strategic management, really? Inductive derivation of a consensus definition of the field. Strategic Management Journal, 28(9), 935–955.

Nembhard, I. M., & Edmondson, A. C. (2006). Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(7), 941–966.

Nielsen, S. (2010). Top management team diversity: A review of theories and methodologies. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(3), 301–316.

Nielsen, B. B., & Nielsen, S. (2012). Top management team nationality diversity and firm performance: A multilevel study. Strategic Management Journal, 34(3), 373–382.

Nielsen, B. B., & Nielsen, S. (2013). Top management team nationality diversity and firm performance: A multilevel study. Strategic Management Journal, 34(3), 373–382.

Oakley, J. G. (2000). Gender-based barriers to senior management positions: Understanding the scarcity of female CEOs. Journal of Business Ethics, 27(4), 321–334.

Olie, R., van Iterson, A., & Simsek, Z. (2012). When do CEOs versus top management teams matter in explaining strategic decision-making processes? International Studies of Management and Organization, 42(4), 86–105.

Olson, B. J., Parayitam, S., & Yongjian, B. (2007). Strategic decision making: The effects of cognitive diversity, conflict, and trust on decision outcomes. Journal of Management, 33(2), 196–222.

Parola, H. R., Ellis, K. M., & Golden, P. (2015). Performance effects of top management team gender diversity during the merger and acquisition process. Management Decision, 53(1), 57–74.

Perryman, A. A., Fernando, G. D., & Tripathy, A. (2016). Do gender differences persist? An examination of gender diversity on firm performance, risk, and executive compensation. Journal of Business Research, 69(2), 579–586.

Peterson, R. S., Martorana, P. V., Smith, D. B., & Owens, P. D. (2003). The impact of chief executive officer personality on top management team dynamics: One mechanism by which leadership affects organizational performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 795–808.

Powell, T. C. (2011). Neurostrategy. Strategic Management Journal, 32(13), 1484–1499.

Prahalad, C. K., & Bettis, R. A. (1986). The dominant logic: A new linkage between diversity and performance. Strategic Management Journal, 7(6), 485–501.

Qin, J., Muenjohn, N., & Chhetri, P. (2013). A review of diversity conceptualizations: Variety, trends, and a framework. Human Resource Development Review, 13(2), 133–157.

Quigley, T. J., & Hambrick, D. C. (2015). Has the “CEO effect” increased in recent decades? A new explanation for the great rise in America’s attention to corporate leaders. Strategic Management Journal, 36(6), 821–830.

Quintana-García, C., & Benavides-Velasco, C. A. (2016). Gender diversity in top management teams and innovation capabilities: The initial public offerings of biotechnology firms. Long Range Planning, 49(4), 507–518.

Ragins, B. R., Townsend, B., & Mattis, M. (1998). Gender gap in the executive suite: CEOs and female executives report on breaking the glass ceiling. The Academy of Management Executive, 12(1), 28–42.

Rayner, S. (2009). Educational diversity and learning leadership: A proposition, some principles and a model of inclusive leadership? Educational Review, 61(4), 433–447.

Rogelberg, S. G., & Rumery, S. M. (1996). Gender diversity, team decision quality, time on task, and interpersonal cohesion. Small Group Research, 27(1), 79–90.

Rosener, J. (1990). How women lead. Harvard Business Review, 68(6), 119–125.

Ruigrok, W., Peck, S., & Tacheva, S. (2007). Nationality and gender diversity on Swiss corporate boards. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 15(4), 546–557.

Ruiz-Jiménez, J. M., del Mar Fuentes-Fuentes, M., & Ruiz-Arroyo, M. (2016). Knowledge combination capability and innovation: The effects of gender diversity on top management teams in technology-based firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 135(3), 503–515.

Ryan, J. (2014). Promoting inclusive leadership in diverse schools. In I. Bogotch & C. M. Shields (Eds.), International handbook of educational leadership and social (in)justice (Vol. 29, pp. 359–380). Heidelberg: Springer.

Shore, L. M., Randel, A. E., Chung, B. G., Dean, M. A., Holcombe Ehrhart, K., & Singh, G. (2010). Inclusion and diversity in work groups: A review and model for future research. Journal of Management, 37(4), 1262–1289.

Shore, L. M., Randel, A. E., Chung, B. G., Dean, M. A., Holcombe Ehrhart, K., & Singh, G. (2011). Inclusion and diversity in work groups: A review and model for future research. Journal of Management, 37(4), 1262–1289.

Sila, V., Gonzalez, A., & Hagendorff, J. (2016). Women on board: Does boardroom gender diversity affect firm risk? Journal of Corporate Finance, 36, 26–53.

Simons, T., Pelled, L. H., & Smith, K. A. (1999). Making use of difference: Diversity, debate, and decision comprehensiveness in top management teams. Academy of Management Journal, 42(6), 662–673.

Simsek, Z., Jansen, J. J. P., Minichilli, A., & Escriba-Esteve, A. (2015). Strategic leadership and leaders in entrepreneurial contexts: A nexus for innovation and impact missed? Journal of Management Studies, 52(4), 463–478. doi:10.1111/joms.12134.

Sugiyama, K., Cavanagh, K. V., van Esch, C., Bilimoria, D., & Brown, C. (2016). Inclusive leadership development: Drawing from pedagogies of women’s and general leadership development programs. Journal of Management Education, 40(3), 253–292.

Talke, K., Salomo, S., & Rost, K. (2010). How top management team diversity affects innovativeness and performance via the strategic choice to focus on innovation fields. Research Policy, 39(7), 907–918.

Tang, Y., Li, J., & Yang, H. (2015). What I see, what I do: How executive hubris affects firm innovation. Journal of Management, 41(6), 1698–1723.

Welbourne, T. M., Cycyota, C. S., & Ferrante, C. J. (2007). Wall street reaction to women in Ipos an examination of gender diversity in top management teams. Group & Organization Management, 32(5), 524–547.

Wuffli, P. A. (2016). Inclusive leadership: A framework for the global era. Cham: Springer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Najmaei, A. (2018). Revisiting the Strategic Leadership Paradigm: A Gender Inclusive Perspective. In: Adapa, S., Sheridan, A. (eds) Inclusive Leadership. Palgrave Studies in Leadership and Followership. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60666-8_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60666-8_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-60665-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-60666-8

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)