Abstract

People can experience intense dysphoria when they fail to meet standards important to them, or important to others of consequence. Whether it is moral, competence, or conventional in nature, failure to meet important standards can lead to the emotional experiences of shame or guilt. Academic psychology tends to portray guilt as a constructive dysphoria associated with self-forgiveness, self-improvement, and making amends, whereas shame is portrayed as a debilitating self-castigation associated with avoidance of failure and its consequences. Recent theory and research, however, has bolstered a consistent, if iconoclastic, criticism that shame and guilt are not polar opposite forms of dysphoria that move people in opposite directions. Instead, guilt and shame may be better thought of close, sibling emotions that differ by degree. Even more importantly, recent theory and research suggests that guilt and shame’s links to self-forgiveness are best understood when analysts specify the exact nature of one’s emotional experience (e.g., feelings of inferiority, rejection, self-reproach) as well as whether one’s failing is more or less likely to be improved with effort.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Understanding Shame and Guilt

People can experience intense dysphoria when they fail to meet standards important to them or important to others of consequence, like family, bosses, coworkers, neighbors, or authority figures (Lazarus, 1991) . Whether it is moral, competence , or conventional in nature, failure to meet important standards can lead to unpleasant, self-critical emotions like shame or guilt. For at least the last several decades, guilt has been viewed as the more useful emotion because it is thought to motivate people to respond constructively to failure (for reviews, see Gilbert & Andrews, 1998; Tangney & Fischer, 1995; Tracy, Robins, & Tangney, 2007) . In fact, guilt is widely thought to include many of the elements considered essential to the process of self-forgiveness, such as acknowledgement of wrongdoing, acceptance of responsibility, and the desire to improve oneself or one’s relationship with others (see Fisher & Exline, 2010; Hall & Fincham, 2005; Woodyatt & Wenzel, 2014) .

Partly because guilt is conceptualized and assessed in such different ways, however, the empirical evidence for guilt’s presumed positive link to self-forgiveness is not consistent across measures or across studies (Carpenter, Tignor, Tsang, & Willett, 2016; Griffin et al., 2016; Woodyatt & Wenzel, 2014) . For instance, Carpenter et al. (2016) found that guilt conceptualized and measured as chronic self-criticism of one’s behavior had a near zero correlation with a general tendency toward self-forgiveness. This is a broader problem in research on guilt (Cohen, Wolf, Panter, & Insko, 2011; Gausel & Leach, 2011) . For example, the correlation between guilt and depression increases with the degree to which guilt is conceptualized and measured as a chronic, generalized self-criticism of one’s behavior (Kim, Thibodeau, & Jorgensen, 2011) .

In contrast to guilt, shame has long been viewed as a more aversive state of self-criticism that is less constructive than guilt (for reviews, see Gilbert & Andrews, 1998; Tangney & Fischer, 1995; Tracy et al., 2007) . As shame is said to be a profound self-criticism of the global self, it is thought to be a devastating blow to self-worth that hamstrings people leaving them barely strong enough to crawl away and hide from their fundamental inadequacy (see Lewis, 1971; Tangney & Dearing, 2002) . The only other escape from shame is thought to be an “externalization ” of the felt inadequacy in the form of angry hostility toward those aware of one’s failure or otherwise vulnerable to one’s wrath (for discussions, see Gausel & Leach, 2011; Tangney & Dearing, 2002) . This so-called humiliated fury, or shame-rage spiral, is an emotion-specific form of Freud’s notion of displacement and is quite similar to the classic explanation of violence dubbed the frustration-aggression hypothesis.

Given the prevailing view of shame, it is not surprising that researchers of self-forgiveness generally expect shame to lead to less self-forgiveness and therefore to lead to less constructive responses to failure, moral or otherwise (see Fisher & Exline, 2010; Hall & Fincham, 2008) . But, here too the evidence is mixed, apparently because of the variety of ways in which shame is conceptualized and measured (e.g., Griffin et al., 2016; Woodyatt & Wenzel, 2014) . For instance, Carpenter et al. (2016) found shame conceptualized and measured as chronic negative self-evaluation to be only weakly correlated to a general tendency toward less self-forgiveness (r = −0.10, −0.19).

In sum, guilt is widely considered a constructive dysphoria about failure whereas shame is considered a dysfunctional and potentially disordered dysphoria (for a review, see Gausel & Leach, 2011) . As such, guilt is thought to lead to self-forgiveness, self-improvement, and making amends, whereas shame is thought to lead to debilitating self-castigation, avoidance of failure and its consequences, and sometimes also the hostile externalization of felt inadequacy. As with all classifications of concepts, such as the DSM or ICD systems of distinguishing between psychological disorders, it is useful to theory, research, and practice to highlight the distinctions between the two dysphoric, self-critical states of shame and guilt. The prevailing view of shame and guilt appears to be especially useful because shame and guilt are thought to be so qualitatively different that they are conceptualized as very much like opposites. As useful as this may be to conceptualizing how shame and guilt should be linked to self-forgiveness, contemporary emotion theory and research offer little support for viewing shame and guilt as opposites. In fact, shame and guilt are more alike than different (for a review, see Gausel & Leach, 2011; Lazarus, 1991) . Both shame and guilt are dysphoric states based in self-criticism for moral or other failure that focus attention on the self (for reviews, see Gilbert & Andrews, 1998; Tangney & Fischer, 1995; Tracy et al., 2007) . And, consistent with this, contemporary emotion research shows there to be small quantitative differences between shame and guilt , rather than the dramatic qualitative differences suggested by conceptualizing them as opposites (for a review, see Gausel & Leach, 2011) .

Thus, as I will explain in some detail, there is little reason to think of shame and guilt as opposite ways of experiencing failure that motivate people to act in opposite ways. To understand how these two emotions can facilitate or inhibit the constructive self-criticism and desire to improve that defines self-forgiveness, we must delve more deeply into the concepts of shame and guilt, to understand more precisely how these emotions are experienced and how the failure that precipitates them, and the context in which they occur, determine their implications for the self and for social relations.

Shame, Guilt, and Debilitation

There are few emotional states thought to be as wholly and as deeply debilitating as shame (for reviews, see Gilbert & Andrews, 1998; Tangney & Dearing, 2002; Tracy et al., 2007) . In a good deal of clinical psychology research, shame is linked with both the “internalized” problems of depression , anxiety , and low self-worth and the “externalized” problems of hostility, aggression, and anti-sociality (for reviews, see Gilbert & Andrews, 1998; Tangney & Dearing, 2002) . And, clinically relevant shame is said to emerge from many, equally horrific, bases—body shame, trauma shame, parental shaming, punitive shaming, the shame of humiliation , or the experience of stigma , all of which can lead to shame and its internalized and externalized problems. Whatever its basis, shame is typically thought to be a debilitating dysphoria that manifests itself across people’s cognitive, affective, and behavioral systems. Shame is seen in negative thinking, pessimism , and cognitive distortion; in the negative affect of internalized states of fear, sadness , and hopelessness ; in externalized states of anger and hostility; and in passive, avoidant, withdrawn distancing from the self and from others (see Ferguson, 2005) .

Although the traditional view of shame as psychologically debilitating and socially disruptive is widely accepted, there is a long-standing view among a minority of academic psychologists that the available quantitative evidence for the traditional view is relatively weak and inconsistent (for reviews, see de Hooge, 2014; Deonna, Rodogno, & Teroni, 2012; Dost & Yagmurlu, 2008; Ferguson, 2005; Ferguson & Stegge, 1995; Gausel & Leach, 2011) . The dramatic qualitative differences expected between shame and guilt are not consistent with the generally small quantitative differences observed in most academic research. Indeed, as relatively self-focused states of sadness in response to self-criticism for perceived failure, most general theories of emotion expect shame and guilt to be more similar than different (Dost & Yagmurlu, 2008; Gausel & Leach, 2011) . Proposals of dramatic qualitative differences, such as that shame is focused on the global self, whereas guilt is focused only on the self’s behavior, take this likely small relative difference between shame and guilt and exaggerate them to suggest that the two emotions are more different in character than is theoretically or empirically possible.

In one recent line of research aimed at clarifying the nature and degree of similarities and differences between shame and guilt , Cohen et al. (2011) isolated the strong criticism of the self in shame from the criticism of the self’s behavior in guilt. Thus, they developed highly specific self-report measures of individuals’ propensity to experience these elements along with measures of the desire to repair or withdraw from failure. When assessed narrowly as strong criticism of the self (e.g., “a despicable human being,” “feel like a bad person”), shame had small links to greater emotional distress, negative affectivity, lower self-esteem , and the desire to avoid one’s failure or those witness to it. This is consistent with the view that shame is a somewhat more profound and intense form of self-criticism than is guilt. However, counter to the traditional view of shame as debilitating psychologically and socially, Cohen et al. found shame and guilt to be more similar than different. In large student and national samples, shame and guilt were both linked to a less anti-social orientation to others. More specifically, shame and guilt both had small to moderate links to less reported aggression (physical and verbal), dishonesty and deceit, unethical decisions, and delinquency at work and in general.

Tangney, Stuewig, and Martinez (2014) recently published an intriguing study that followed an ethnically diverse sample of 482 convicted felons for a year after their release from jail to examine the traditional view of productive guilt and counterproductive shame. Participants’ personal proneness to react to moral and other failures with shame and guilt was assessed while incarcerated. These scores were used to predict self-reported crime and actual arrest a year after release. Contrary to the traditional view, neither guilt nor shame proneness predicted actual arrest (r = −0.08), although guilt did predict less self-reported crime (r = −0.14).

Although there is a long-standing assumption that shame and guilt are highly distinct emotions that represent opposite ways of experiencing failure, there is in fact little theoretical or empirical reason to assume this. Shame and guilt are more alike than different; the small differences between them are a matter of degree. Thus, if we are to properly understand how dysphoria about failure is likely to be linked to self-forgiveness we need to dig deeper into the specific ways in which moral or other failure is experienced rather being satisfied with the fairly vague terms (conceptually and linguistically) of shame and guilt (Gausel & Leach, 2011) . Indeed, the feeling of global inferiority in an important aspect of the self that is seen as difficult to improve is a more precise characterization than is “shame” of the emotional state that is likely to prove an obstacle to self-forgiveness.

The Role of Global Inferiority

The contemporary view of shame in psychological research owes a great deal to psychoanalyst Helen Block Lewis’s (1971) pioneering analyses of her therapy sessions with clients and the translation of these ideas to personality and social psychology by June Price Tangney , mainly in the 1990s (for a review, see Tangney & Dearing, 2002) . According to this view, shame is a debilitating and counterproductive experience of failure because shame is, at its heart, an extremely brutal castigation of the whole self by the self. It is the inference that one’s failure to be honest, or kind, or competent reveals a fundamental and thus difficult to improve flaw in one’s character. Despite this fairly clear conceptualization of shame as debilitating because it is a sense of global inferiority, research on shame rarely isolates this presumably important element of shame to better understand the emotion and its effects.

It is uncontroversial that a sense of global inadequacy is devastating to the self-concept and can undermine basic self-worth in a way that paralyzes people. Indeed, felt inferiority and debilitating paralysis are central to the cognitive distortions, negative thinking, and behavioral inhibition widely viewed as defining symptoms of depression (see Gilbert & Andrews, 1998; Kim et al., 2011; Tangney & Dearing, 2002) . The question, however, is whether shame necessarily involves such profound and unchanging inadequacy. If a sense of global inferiority is what explains why the experience of shame is sometimes debilitating, then it makes sense, conceptually and empirically, to examine the sense of global inferiority directly rather than to examine it indirectly through the concept of shame, which may or may not imply global inferiority (Gausel & Leach, 2011) .

The developmental psychologist Tamara Ferguson has argued for over two decades that the development of shame and guilt in children suggests against the idea that shame is routinely experienced as the self-castigation of the whole self for being profoundly and unalterably inadequate (for reviews, see Ferguson, 2005; Ferguson & Stegge, 1995) . As such, she eschews the traditional view that portrays these two emotions as highly distinct or even opposite. She suggests that what distinguishes shame from guilt is more subtle. According to Ferguson, shame can be more aversive than guilt because in shame people believe that their failure reflects an important shortcoming in who they are as a person. Guilt is relatively more focused on one’s behavior rather than on one’s identity . Thus, according to Ferguson, shame can be debilitating if one views one’s whole person as fundamentally flawed, but it need not be so severe if the view of oneself is not so severe.

Ferguson’s view suggests that psychological and social dysfunction should be linked to shame that is based in a sense of global inadequacy (for a review, see Gausel & Leach, 2011) . And, there is a wide variety of quantitative evidence consistent with this idea. For instance, Kim et al. (2011) performed an empirical synthesis of 108 different studies that examined the strength of the links between reported depression symptoms and reported shame and guilt. They found that chronic shame and shame that was generalized to the self as whole rather than tied to specific circumstances and experiences were moderately linked to depression symptoms. Importantly, chronic and generalized experiences of guilt were about as strongly linked to depression across studies. As chronic and generalized self-criticism of the global self is a key aspect of depression, it is this aspect of dysphoria that should be most logically linked to depression whether people label their experience as “shame,” “guilt,” or something else entirely. Research that includes a sense of inadequacy in its assessment of shame, or assesses shame as necessarily chronic or generalized, is therefore likely to observe that shame is linked to depression and other indicators of psychological debilitation. The same is likely true for assessments of shame that assume that it is a personality-based proneness to make chronic or generalized self-criticism of the self as a whole (see Tangney & Dearing, 2002) .

In several recent studies, Gausel , Leach , and colleagues have examined the idea that global inferiority can explain why shame is debilitating and counterproductive by focusing more finely on the language that people use to describe their experiences of shame about failure. In studies of English and Norwegian speakers, they isolated the feeling of inferiority from the feeling of shame in general and from the feeling of rejection and isolation that can often accompany feelings of inferiority or shame. For instance, Gausel, Leach, Vignoles, and Brown (2012) conducted two studies of about 400 everyday Norwegians’ responses to evidence of their society’s recent genocidal practices against an ethnic minority. They found that a sense that this wrongdoing suggested a specific defect in Norwegians’ character was associated with highly distinct feelings of inferiority and shame. And, the more that individual Norwegians saw themselves as typical of the group, the more shame and especially the more inferiority they felt. When empirically isolated from the distinct feeling of shame about this moral failure, only the feeling of inferiority was linked to withdrawal and other self-defensive motivation. Gausel, Vignoles, and Leach (2016) used similar assessments of the multifaceted experience of shame about either a personal wrong against a loved one or an imagined betrayal of a friend. Here, too a sense that the moral failure revealed a specific defect in the self was linked to the distinct feelings of inferiority and shame. And, in Study 1, the feeling of shame appeared to predict the self-defensive motivation to avoid the failure and those aware of it only before shame was empirically distinguished from the feeling of inferiority and other feelings and interpretations of the failure.

This is an admittedly brief, and incomplete, review of quantitative research on the traditional view of shame as necessarily debilitating psychologically and counterproductive socially. Nevertheless, there is consistent and convincing evidence that the traditional view is in need of amendment. Shame is not necessarily linked to low self-worth, negative thinking, avoidance , withdrawal, or the internalized and externalized problems long thought to be associated with it. Instead, it seems that it is the experience of shame based in, or expressed in, a sense of global inferiority that is debilitating psychologically and that orients people to self-defensive and anti-social responses such as hostile lashing out. As Ferguson has argued, this particular form of inferiority-based shame is not common in healthy children and adults. This fact does not diminish its importance as a psychological and social phenomenon. Rather, understanding the particular potency of inferiority-based shame enables researchers and practitioners alike to better understand people’s experiences. Of course, more finely conceptualizing and studying shame that is based in a sense of global inferiority also allows us to better examine and understand the other forms in which shame may come (see Gausel & Leach, 2011; Leach & Cidam, 2015) . These other forms are likely to be decidedly less debilitating and destructive than the inferiority-based shame that has garnered so much attention and come to stand in for shame in general.

Shame Can Be Constructive

Viewing shame as coming in different forms that are more precisely characterized by distinct cognitive appraisals of failure and feelings about it enables us to consider why and when shame might be a productive form of self-criticism that motivates constructive effort at the improvement of the self and of the social relations affected by one’s failure. In fact, even a conceptual openness to the possibility that shame may be sometimes productive enables reassessment of past quantitative evidence free of the assumption that shame is necessarily debilitating and destructive. In 2011, Gausel and Leach reviewed a good deal of the most prominent quantitative research on shame and guilt to show that numerous studies purported to demonstrate the qualitatively different natures of shame and guilt actually showed the two emotions to be more similar than different (see also Ferguson, 2005) . Thus, in many instances, shame and guilt were about equally linked to many of the ways of thinking and feeling that define the constructive self-criticism of self-forgiveness. For example, many studies over the last 20 years have found that shame and guilt have about equal moderately positive associations with empathizing with others and taking their perspective (Gausel & Leach, 2011) .

In addition, a recent wave of studies shows that recalled or present episodes of shame lead to greater desire for self-improvement (e.g., de Hooge, Zeelenberg, & Bruegelmans, 2010; Lickel, Kushlev, Savalei, Matta, & Schmader, 2014) , cooperative behavior (de Hooge, Bruegelmans, & Zeelenberg, 2008), and pro-social orientation toward those affected by one’s moral failure (Gausel et al., 2016). For example, the aforementioned studies of Gausel et al. (2012) found Norwegians’ reported feelings of shame about their country’s genocidal practices to be moderately linked to a contrite orientation whereby individuals wanted to express their sense of responsibility and remorse to members of the victimized group. And, Gausel et al. (2016) found shame about personal moral failures to predict contrition in addition to the desire to compensate the victim and repair the psychological and material damage done. Also, in the above discussed student and national samples of Cohen et al. (2011) , shame and guilt were both linked to a more pro-social orientation to others. More specifically, guilt, and to a somewhat lesser degree shame, had small to moderate associations with more self-reported empathy, moral values and concerns, honesty, altruism , and a desire to repair the consequences of one’s failures.

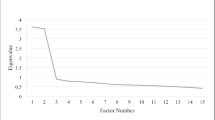

Perhaps because it directly counters the prevailing view of shame as maladaptive and guilt as adaptive, theory and research on the constructive potential of shame and on the subtle distinctions between shame and guilt does not appear to have penetrated the mainstream of academic or clinical understanding. Despite the long-standing arguments of researchers like Ferguson , and the spate of recent research in the last decade showing shame to be less debilitating and destructive than is widely presumed, the traditional view appears to still be the prevailing view. Paradigms of understanding may persevere in the face of disconfirming evidence partly because individual disconfirmations can be seen as anomalous and because no more general paradigm has been offered to integrate the traditional view with the new view. To address these concerns, Leach and Cidam (2015) recently offered an integrative model of when shame evokes constructive motivation after failure and when it elicits the opposite. To avoid the dismissal of evidence for constructive shame as anomalous, Leach and Cidam performed a meta-analysis to quantitatively synthesize published research rather than conducting their own studies.

Concerned that the effects of shame cannot be properly understood without attention to the nature of the failure about which it is experienced, Leach and Cidam (2015) reasoned that shame is most likely to be positively linked to the motivation to constructively approach failure and its consequences when the person or the context leads to the interpretation of the failure as likely to improve with effort. Thus, a belief that the self is alterable in ways that allow for personal betterment or a belief that the damage done to others can be repaired (perhaps by apology or restitution) should change the quality of the shame experience in a way that makes the serious self-criticism of a specific defect in the self more manageable and thus more motivating of change. In contrast, when the person or the context leads to the interpretation of the failure as unlikely to improve with effort, shame will probably be experienced as debilitating. Indeed, an unalterable defect in the self will probably be experienced as the profound sense of inferiority that is well known for its debilitating and destructive effects.

In a meta-analysis of 90 samples totaling more than 12,000 participants, Leach and Cidam (2015) examined each study to ascertain whether the method or measurement implied that the failure in question was more or less likely to be improvable with effort. Some studies gave participants an explicit message that their failure was improvable by instructing them that they would have another chance at a task or that they could take some time to learn how to perform better. Other studies implied that a failure was very difficult to improve by offering only high stakes tasks that were difficult to succeed at or to improve upon. Across these two types of studies, Leach and Cidam found both shame and guilt to be equally linked to pro-sociality and self-improvement when the context suggested that failure was more reparable. However, when the context suggested that failure was less reparable, shame was negatively linked to constructive approach motivation and behavior, whereas guilt’s link remained positive. This suggests that the key to self-forgiveness, and to other constructive responses to failure, is the possibility of repair and improvement that color the experience of shame and guilt in ways that make these emotions more constructive. As with other efforts to more precisely characterize how shame and guilt are experienced about failure, Leach and Cidam’s (2015) effort to contextualize shame and guilt by taking into account the nature of the failure aims to more finely distinguish why shame and guilt motivate people to either constructively approach or defensively avoid their failure and its consequences. This sort of precision in theory and measurement is important to the production and interpretation of research that can improve our understanding of shame and guilt, and their roles in the process of constructive responses to failure, such as self-forgiveness. Of course, this sort of precision can aid those who aim to understand people’s experience of shame and guilt in a way that allows them to encourage and facilitate the therapeutic process of self-forgiveness.

Shame, Guilt, and Social Image

Up to this point, I have focused on shame and guilt as personal emotions based in a concern for the ways in which a moral, competence , or other failure calls one’s self-image into question. However, in the more social end of psychology, and in numerous social sciences, shame is conceptualized and studied as based in a concern for the way in which a failure may call into question one’s reputation or social image in the eyes of others (for reviews, see de Hooge, 2014; Gausel & Leach, 2011) . In the aforementioned studies by Gausel, Leach , and colleagues, concern for the way that a moral failure might damage one’s social image was also examined as an alternative basis of “shame.” For instance, Gausel et al. (2012) found Norwegians’ concerns that other countries would condemn them for their genocidal practices to be the central explanation of their motivation to hide their failure and to avoid its consequences. This concern for condemnation operated mainly through a feeling of rejection and isolation, which was strongly tied to a feeling of inferiority. Indeed, a great deal of prior research shows that feared condemnation from others and the feelings of rejection and isolation that often follow from it are an important basis of felt inferiority . Being devalued by others is at least as strong a basis of felt inferiority than self-criticism .

In the studies of Gausel et al. (2016) , we experimentally manipulated this concern for condemnation by, for example, leading participants to believe that others in the study would hear about the mistreatment of a family member that the participant reported anonymously. Although the others would not necessarily know who the perpetrator was, participants had reason to be concerned that their act would be condemned and that they might somehow be found out. As a result, participants expressed strong concern that their social image would be damaged and that they would feel rejected and isolated as a result. In other words, participants worried that their failure would lead to damage to their social image that was unlikely to be improved through effort. Of course, one’s social image is not always so difficult to improve. As Gausel and Leach (2011) discussed, work on appeasement, the maintenance of social bonds, and reintegrative shaming, among other work, all suggest that people may act pro-socially toward others in an effort to repair their social image after a failure that is known by important or consequential others. In the meta-analysis discussed above, Leach and Cidam (2015) assessed the combined evidence from seven studies, mainly by de Hooge and colleagues, which gave participants an opportunity to act pro-socially toward people who had witnessed participants’ moral or achievement failure. In these studies, where their social image was clearly improvable, participants’ shame had a moderately positive link to constructive approach motivation or behavior (e.g., to help others).

Distinguishing shame about a more or less reparable social image called into question by failure helps to further specify the different forms that shame can take. Indeed, Woodyatt and Wenzel (2014) recently relied on the social image oriented form of shame to argue against the prevalent view that shame undermines self-forgiveness. They argued that when based in a concern for one’s moral standing in a community , shame should motivate efforts to improve one’s social image by demonstrating to others that one is of sufficient moral character to recognize, acknowledge, and repair one’s moral or other failures (see also Gausel & Leach, 2011) .

Conclusion

The productive self-criticism of self-forgiveness appears to be crucial to personal improvement after moral or other failure. It seems obvious that the acknowledgement of, and specific self-criticism for, failure are necessary first steps to identifying what specific aspects of the self need improvement after failure. Feeling bad about this aspect of the self seems to be part and parcel of working through one’s failure. For what are likely a variety of reasons, researchers of self-forgiveness and of shame and guilt have focused on this dysphoria and expected it to be so painful and damaging to self-worth that it would undermine productive self-criticism by leading people to do whatever they could to avoid the failure that precipitated the pain. In other words, shame was thought to be so aversive to people that experiencing self-criticism in this way was presumed to lead to self-defense rather than honest self-assessment and humble effort at self-improvement.

To be sure, there is ample theory and research in support of the view that shame about failure can be debilitating and lead people in directions opposite to the productive self-criticism that appears to facilitate individuals’ efforts to constructively approach their failure in order to arrive at self-forgiveness. However, rather than thinking of this highly aversive state as shame in general, it is more precise to think of this as a specific form of shame defined by a felt inferiority about a whole self or important part of the self that is believed to be beyond redemption. People who experience this sense of inferiority are likely to suffer from the internalized (e.g., self-loathing , pessimism, depression , self-destructive behavior) and externalized (e.g., distrust and dishonesty, hostility, lashing out) problems that have been traditionally associated with shame. Theorists, researchers, and clinicians may better understand and better help those struggling with inferiority -based shame by seeing it for what it is. Conflating inferiority-based shame with shame in general, or with a shame based in a belief that one’s social image is irreparably damaged by a failure, muddies the potentially important distinctions between these social psychological states.

Giving inferiority-based shame its due in the process of self-criticism also enables a finer view of the other forms that shame can take. Most notably, it enables the conceptualization, examination, and intervention in the more potentially productive state of shame that is based in a view of the failed self as improvable. As a dysphoric state of self-criticism, the emotional experience of shame and the attendant cascade of cognitive, neurological, physiological, and bodily processes can serve as a signal that some aspect of ourselves requires serious attention and effort. If we believe, or are led to believe, that this aspect of our self is improvable, a focus on what is wrong can heighten our attention and concentrate our effort. Feeling bad about a failure is probably not necessary to productive self-criticism for it, but the dysphoria in shame is a powerful phenomenological sign that we should take our failure seriously (see Lazarus, 1991) . Of course, the outward manifestation of our shame—lowered head, frowning face, constricted body posture, withdrawal, and other behavioral inhibition—can also signal to important others that we are taking our failure seriously and are aware of its potential to damage our self-image and our social image (for discussions, see de Hooge, 2014; Gausel & Leach, 2011) . This serious, sad, but sensible response can be a key part of the productive self-criticism referred to as self-forgiveness, inside and out.

Although pioneering shame theorist Lewis (1971) saw shame about less reparable social image as a particularly immature dependence on others, this likely underestimates the importance of our social image to our psychological and social well-being . People do sometimes fail in ways that make it near impossible for others to see them as anything other than a failure deserving of condemnation. This is a potent basis of devastating feelings of rejection and isolation as well as a profound sense of inadequacy. It is not at all surprising that those who experience a failure as inviting condemnation from important others tend to be motivated to do what they can to run away, hide, lash out, or otherwise defend their self-image and their social image against such a serious threat. As such, it should be no surprise that people are motivated to work to improve their social image after failure by improving themselves and/or improving their social image directly. As social creatures, we want to appear at least minimally successful to those on whom we depend for psychological (like respect) and material (like food) resources. In many ways, the notion of self-forgiveness seems to suggest that efforts at self-improvement are most important in the process of productive self-criticism even if such effort also improves one’s social image (see Woodyatt & Wenzel, 2014) . However, avoiding condemnation from important others is a potent motivator of moral and other effort that should not be underestimated in comparison to the motivator of improving one’s self-image in one’s own eyes. Future work on shame and guilt in self-forgiveness would be wise to integrate processes of self-forgiveness with those of receiving other’s forgiveness to better integrate forms of shame more concerned with self-image with those concerned with social image. The plasticity of shame as an emotional experience is one advantage to using it as a way to characterize the dysphoria about failure that seems so important to understanding who, when, and why people respond constructively to failure in important domains of their lives that question their character.

References

Carpenter, T. P., Tignor, S. M., Tsang, J. A., & Willett, A. (2016). Dispositional self-forgiveness, guilt- and shame-proneness, and the roles of motivational tendencies. Personality and Individual Differences, 98, 53–61.

Cohen, T. R., Wolf, S. T., Panter, A. T., & Insko, C. A. (2011). Introducing the GASP scale: A new measure of guilt and shame proneness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 947–966.

de Hooge, I. E. (2014). The general sociometer shame: Positive interpersonal consequences of an ugly emotion. In K. G. Lockhart (Ed.), Psychology of shame: New research (pp. 95–110). New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers.

de Hooge, I. E., Bruegelmans, S. M., & Zeelenberg, M. (2008). Not so ugly after all: When shame acts as a commitment device. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 933–943.

de Hooge, I. E., Zeelenberg, M., & Bruegelmans, S. M. (2010). Restore and protect motivations following shame. Cognition and Emotion, 24, 111–127.

Deonna, J. A., Rodogno, R., & Teroni, F. (2012). In defense of shame: The faces of an emotion. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Dost, A., & Yagmurlu, B. (2008). Are constructiveness and destructiveness essential features of guilt and shame feelings respectively? Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 38, 109–129.

Ferguson, T. J. (2005). Mapping shame and its functions in relationships. Child Maltreatment, 10, 377–386.

Ferguson, T. J., & Stegge, H. (1995). Emotional states and traits in children: The case of guilt and shame. In J. P. Tangney & K. W. Fischer (Eds.), Self-conscious emotions: Shame, guilt, embarrassment, and pride (pp. 174–197). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Fisher, M. L., & Exline, J. J. (2010). Moving toward self-forgiveness: Removing barriers related to shame, guilt, and regret. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4, 548–558.

Gausel, N., & Leach, C. W. (2011). Concern for self-image and social-image in the management of moral failure: Rethinking shame. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 468–478.

Gausel, N., Leach, C. W., Vignoles, V. L., & Brown, R. J. (2012). Defend or repair? Explaining responses to in-group moral failure by disentangling feelings of shame, rejection, and inferiority. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 941–960.

Gausel, N., Vignoles, V. L., & Leach, C. W. (2016). Resolving the paradox of shame: Feelings about moral failure and risk to social image explain pro-social and self-defensive motivation. Motivation and Emotion, 40, 118–139. doi:10.1007/s11031-015-9513-y.

Gilbert, P., & Andrews, B. (1998). Shame: Interpersonal behavior, psychopathology, and culture. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Griffin, B. J., Moloney, J. M., Green, J. D., Worthington, E. L., Jr., Cork, B., Tangney, J. P., … Hook, J. N. (2016). Perpetrators’ reactions to perceived interpersonal wrongdoing: The associations of guilt and shame with forgiving, punishing, and excusing oneself. Self and Identity, 15, 650–661.

Hall, J. H., & Fincham, F. D. (2005). Self-forgiveness: The stepchild of forgiveness research. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24, 621–637.

Hall, J. H., & Fincham, F. D. (2008). The temporal course of self-forgiveness. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27, 174–202.

Kim, S., Thibodeau, R., & Jorgensen, R. S. (2011). Shame, guilt, and depressive symptoms: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 68–96.

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaption. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Leach, C. W., & Cidam, A. (2015). When is shame linked to constructive approach orientation? A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109, 983–1002.

Lewis, H. B. (1971). Shame and guilt in neurosis. New York, NY: International Universities Press.

Lickel, B., Kushlev, K., Savalei, V., Matta, S., & Schmader, T. (2014). Self-conscious emotions and motivation to change the self. Emotion, 14, 1049–1061.

Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. L. (2002). Shame and guilt. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Tangney, J. P., & Fischer, K. W. (1995). Self-conscious emotions: Shame, guilt, embarrassment, and pride (pp. 174–197). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Martinez, A. G. (2014). Two faces of shame: The roles of shame and guilt in predicting recidivism. Psychological Science, 25, 799–805.

Tracy, J. L., Robins, R. W., & Tangney, J. P. (2007). The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Woodyatt, L., & Wenzel, M. (2014). A needs-based perspective on self-forgiveness: Addressing threat to moral identity as a means of encouraging interpersonal and intrapersonal restoration. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 50, 125–135.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Leach, C.W. (2017). Understanding Shame and Guilt. In: Woodyatt, L., Worthington, Jr., E., Wenzel, M., Griffin, B. (eds) Handbook of the Psychology of Self-Forgiveness. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60573-9_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60573-9_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-60572-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-60573-9

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)