Abstract

Menopause is a phenomenon experienced by women as they approach middle age, marking the end of menstruation and reproduction. Throughout history, menopause has been classified in negative terms as a malady and decay of femininity necessitating a cure, which led to the controversial development of hormone replacement therapy. Feminists and activists challenged existing stereotypes and emphasized menopause as a natural transition. There is still little consensus on universal menopause symptoms since wide variations are reported across geographic regions and cultures. These differences can be better examined via individual menopausal experiences, which are unique and shaped by attitudes and expectations. Macro-level structures often place psychosocial constraints on individual women imposing roles after menopause or creating expectations of common symptoms. This chapter applies three theoretical frameworks to the menopausal experience. The biomedical model portrays menopause as a result of biological pathways with clear diagnoses of menopausal stages and is widely used by physicians. The life course perspective views menopause as a lifelong process that is shaped by the current time period with early life advantages or disadvantages that affect women as they enter their menopausal years. The biopsychosocial model integrates women's experiences of menopause into a hierarchy of structures. Each woman is shaped by microlevel factors like genetics and body functions while also influenced by macro-level structures within her family or society. As the number of women experiencing menopause rises with emerging demographic shifts, special consideration to individual and global experiences of menopause should be integrated to advance well-being.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

As women advance through the life course, they enter into the climacteric period defined as the post-reproductive phase (International Menopause Society, 2016). This period is defined by menopause , a natural phenomenon signaling the decline of ovarian function and onset of the last menstrual period (National Institute on Aging, 2013). Menopause is generally diagnosed in retrospect since the onset is defined as a 12-month cessation of menstrual periods (Barnabei, 2007). The climacteric transition may last a few months or several years typically beginning as a woman reaches her mid-40s to mid-50s with 51.3 years reported as the average age (Brinton, Gore, Schmidt, & Morrison, 2009). Clinical definitions and common symptoms of menopause can be accessed in Tables 22.1 and 22.2.

Although entry into menopause is universal for aging women, the experience is far from uniform. There has been little consensus on menopausal symptoms with wide variations across geographic regions and cultures. Similarly, treatment has been problematic with differing philosophies between natural and medical interventions. The understanding of femininity and purpose has also been questioned during the menopausal years. Once considered a malady, menopause definitions have changed throughout medical and societal history. The myriad of macro- and micro-level factors affecting a woman’s menopause experience is explored in this chapter.

We begin by introducing the historical context surrounding the treatment and perceptions of menopause evolution over time. There are significant implications globally for menopause in the emerging demographic shifts in older adult populations. Both individual-level psychological factors and sociocultural considerations frame the landscape of the menopausal experience. We then compare different theories and frameworks on menopause. We examine the biomedical approach as the most prevalent method of clinical understanding of the climacteric period. Next, we discuss how the life course perspective intersects history, time, and a woman’s life trajectory in the entry into menopause. Finally, we introduce the biopsychosocial model, which examines the influence of hierarchical systems operating on the individual woman in her experience of menopause.

Menopause History

Throughout time, menopause has been associated with mostly negative connotations. In 1892, Regis de Bordeaux, a French physician, injected an ovarian abstract into a patient to treat her menopausal “insanity” (McCrea, 1983). Similarly in the psychology sector, prominent psychologist Sigmund Freud described menopause as an “anxiety neurosis” and physical illness in the early twentieth century (as cited in Spira & Berger, 1999, p. 2). In 1945, psychologist Helen Deutsch likened menopause to puberty and described menopause as “woman’s last traumatic experience as a sexual being” (as cited in Spira & Berger, 1999, p. 2). In one more positive depiction, Colombat de L’Isere in 1845 stated that in menopause, “women now cease to exist for the species, and henceforward live only for themselves” (as cited in Utian, 1997, p. 75).

Well into the twentieth century, menopause remained a condition of deficiency and loss of womanhood (Spira & Berger, 1999). In the 1960s, gynecologist Robert A. Wilson established estrogen replacement therapy to treat lack of hormones,which he believed would enhance youth, maintain femininity, and mitigate aging (Huss, 1966; Voda & Ashton, 2006; Wilson, 1968). Wilson also published a widely distributed book, Feminine Forever , claiming menopause to be a decay and a threat to feminine essence (McCrea, 1983; Wilson, 1968). In 1969, physician David Reuben’s bestseller, Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex , described menopause as “estrogen is shut off, a woman becomes as close as she can to being a man … having outlived their ovaries, they have outlived their usefulness as human beings” (as cited in Foxcroft, 2010, p. 4). Rueben also touted estrogen replacement as a way to “turn back the clock (as cited in McCrea, 1983). During this period and the next decade, sales of estrogen therapy were at an all-time high with 51% of women using estrogens over a median duration (McCrea, 1983).

The estrogen therapy popularity began to burst in late 1975, as links were made between estrogen use and uterine cancer in the scientific literature (McCrea, 1983; Utian, 1997). By 1979, the US National Institute on Aging established an estrogen and postmenopausal consensus finding that estrogens increased risk of endometrial cancer but were the only treatment of hot flashes and vaginal atrophy; this concluded in a recommendation of low-dose treatment and informed decision making (McCrea, 1983).

In a counter movement, the backlash from these claims led to women’s groups and feminists to challenge the menopause narrative and disease label. Therese Benedek (1973) pointed towards cultural expectations of women in sexual and reproductive roles and thus how menopause brings upon fear and loss. She also connected the decline in hormones and sexualization towards a positive middle age of exploration (Benedek, 1973). The acceptance of menopause as a normal process and realization that myths of inadequacy foster sexism began to emerge (McCrea, 1983). Betty Friedan, an American writer and feminist, emphasized successful aging and rebelling from Western expectations in her 1993 book, The Fountain of Age (Foxcroft, 2010).

The feminist leaders not only challenged societal norms but also fought against estrogen hormonal therapy through advocacy and publications in the late 1970s (McCrea, 1983). These efforts later led to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to require patient package inserts warning of cancer and risks of estrogen and progesterone. The emergence of major menopause societies like International Menopause Society (IMS) and the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) was also cofounded during similar time periods to establish best clinical and research practices in menopause (Utian, 1997).

The Women’s Health Initiative began two decades later in 1993 through the US National Institutes of Health as a result of hormone replacement therapy concerns and ongoing advocacy. This initiative consisted of a major randomized clinical trial evaluating the effects of hormonal therapy on heart disease, stroke, and breast cancer (Voda & Ashton, 2006). Results reported that estrogen and progesterone combined therapy increased risk of stroke, heart disease, and breast cancer but estrogen-only therapy increased stroke risk but had no effect on heart disease or breast cancer risks. These findings led to a tumultuous shift in menopause management with the reemergence of hormonal therapy (Voda & Ashton, 2006). Hormone replacement therapy was subsequently integrated into the NAMS (North American Menopause Society) recommendations. The current landscape of menopause is a mixture of historical influences that are still prevalent in the medical field and management of menopause still including the option of hormonal replacement therapy with health caveats.

Global Demographic Transitions

As we move from historical perspectives, we must consider the important demographic shifts. A growing population distribution of aging adults will be witnessed throughout the world. An estimated two billion people over the age of 60 will be alive in 2050 (WHO, 2015). Since women tend to have higher life expectancies than men in most countries, preparing globally for the incoming cohorts of women experiencing menopause and related transitions is salient. In fact, there are nearly 879 million women today within the typical menopausal age range between 40 and 60 years (Brinton, Yao, Yin, Mack, & Cadenas, 2015; U.S. Census Bureau, 2016). With overall life expectancies increasing globally, the menopause experience and postmenopause years will be a significant and lengthy life stage for women.

Physiologic symptoms during menopause are also subjective based upon geography. After a study of literature on menopausal symptoms across 100 research studies in different countries, patterns of symptoms were found but there were no clear universal symptoms (Obermeyer, 2000). For example, the United States and Canada had the highest prevalence of hot flashes while Japan had the lowest (ibid). In Ghana, the most commonly reported menopause symptoms were fatigue, insomnia, palpitations, and weight gain (Kwawukume, Ghosh, & Wilson, 1993). In Nigeria, women most commonly reported symptoms of joint and muscular discomfort, physical or mental exhaustion, sexual problems, and hot flashes (OlaOlorun & Lawoyin, 2009). Research exploring sexual function after menopause and difficult or painful sexual intercourse found that women in Asian countries reported lower frequencies compared to US or European populations, where nearly one in three women reported sexual difficulties (Obermeyer, 2000). These studies suggest that symptoms fluctuate in frequency reports depending on the subpopulation and context (Obermeyer, 2000).

When exploring intra-country differences in menopause symptom experiences, variation is also observed across subcultures. The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) is a US-based multiracial and ethnic investigation of menopausal symptoms from Caucasian, African-American, Chinese, Japanese, and Hispanic women (Avis et al., 2001). The study found that Chinese and Japanese groups reported the fewest symptoms while Caucasian women reported more psychosomatic symptoms and African-American women reported more vasomotor symptoms (Avis et al., 2001). The SWAN investigation did not uncover a single menopause syndrome experienced by all women across the country. Another US study supported these findings and found that African-American women were more likely to experience hot flashes compared to Caucasian women (Grisso, Freeman, Maurin, Garcia-Espana, & Berlin, 1999).

As we discuss the history and treatment of menopause beyond straightforward clinical diagnoses, we want to explore the menopause experience as more than biological processes but rather as partial social constructions. Institutionalized sexism and influence of physicians have shaped the menopause dialogue. Social structures have also led to the variation observed in the roles of women after menopause and their varying symptoms during menopause. When we apply these broader external considerations to the individual woman, we can better understand how these structures impact menopause.

Psychosocial Factors

The historical and demographic importance of menopause helps us to understand the temporal knowledge of aging and significant implications for this generation. As the understanding of menopause expands, factors related to a woman’s transition also shift from a pure clinical diagnosis. Menopause interlinks biological, social, and cultural components in a woman’s life (Spira & Berger, 1999). We specifically explore broad psychological and sociocultural factors and later detail some of these experiences from theoretical frameworks.

Psychological Factors

Women’s attitudes towards menopause have a significant role in the experience of symptoms. In one systematic review, women with more negative attitudes towards menopause reported more symptoms (Ayers, Forshaw, & Hunter, 2010). In another review of diverse cultural groups, most of the negative attitudes towards menopause arose from women that had surgical menopause, women that highly prioritize fertility , and women who reach menopause before achieving the number of desired children (Jones, Jurgenson, Katzenellenbogen, & Thompson, 2012).

In a qualitative study conducted in Iran, middle-aged women expressed psychological concerns and preoccupations with the past, future, personal health, family, and finances which were persistent themes (Sharifi, Anoosheh, Foroughan, & Kazemnejad, 2014). Women felt an increased burden due to their roles of parent caretaking and spousal responsibilities. Several psychological tensions felt by the studied women were undesirable physical changes, declining health, menopausal symptoms, decreased mood and mental function, increased tensions, and dissatisfaction with aging (Sharifi et al., 2014).

In a study conducted in Nigeria, mental health was emphasized as a way to advocate for positive attitude tools for women entering into menopause (Osarenren, Ubangha, Nwadinigwe, & Ogunleye, 2009). Participants agreed most frequently with statements about (1) concerns towards how their husband will feel, (2) necessity to see a doctor, (3) menopause as a significant life change, (4) menopause is unpleasant, and (5) feeling freer to do things for themselves after menopause. In an effort to understand the perceptions and concerns of menopausal Nigerian women, targeted medical and psychological interventions can be developed (Osarenren et al., 2009).

The individual expectations and attitudes of women as they enter menopause are related to their overall agency of their transition. An abrupt and early end to their reproductive functions signals a negative outlook while menopause in the middle ages follows expectations in role changes and aging. As symptom management is emphasized in the clinical and pharmaceutical arenas, expansion to psychological health should also be part of menopause care.

Sociocultural Factors

The sociocultural context of women in specific geographical locations affects the meaning and experience of menopause. In the Western world, menopause is treated as if it were a disease necessitating medical intervention rather than a natural phenomenon (Jones et al., 2012). In the Arab world, the rough translation of the word consistent to menopause and midlife means “desperate age ,” signifying a negative cultural perception towards menopause (Jones et al., 2012). Kaufert (1996) pointed out that much of the research on menopause in Asia, Africa, and South America is based on the same questions and study designs elicited in North American and European populations, which may omit unique cultural considerations (Kaufert, 1996).

The menopausal experiences of women have diverse implications across geographic and cultural borders. In Latin American countries, some aging woman may be abandoned by both her husband and children or expected to take care of grandchildren (Kaufert, 1996). Working women in a rural Indian village felt liberated from the bothers of menstruation and liberated to work on their businesses postmenopause (George, 1996). Urban Korean women felt lifted from oppression and transformed from being a wife and mother into transformed women after menopause (Lee, 1997).

The role of sexuality in menopause also merits unique considerations across populations. Some women embrace the ability to engage in sex without pregnancy while other women experience libido decline (Laan & Lunsen, 2009; Leiblum, Koochaki, Rodenberg, Barton, & Rosen, 2006). External factors like family support and societal expectations during menopause shape the experiences of women across regions.

Social and cultural factors may determine the extent that socioeconomic status, nutrition, and chronic diseases may impact the menopausal experience (Meleis, Sawyer, Im, Hilfinger Messias, & Schumacher, 2000). For example, women with poor nutrition had lower bone density and economically deprived women had limitations in workforce transition or menopausal therapy (Kaufert, 1996; Meleis et al., 2000). Additional considerations exist with socioeconomic status since women with lower educational and occupational levels had higher associations with earlier age at natural menopause (Schoenaker, Jackson, Rowlands, & Mishra, 2014).

Sociocultural influences are associated with the types of menopausal symptoms commonly reported. The commonly reported menopause symptoms , such as hot flashes and night sweats in North America, may also bolster expectations among women of similar symptoms while disregarding uncommon symptoms as they transition into menopause (Boulet, Oddens, Lehertb, Vemer, & Visser, 1994; Kaufert, 1996). Some research has suggested that the medical field and physicians have dictated the symptom experiences in conjunction with cultural expectations (Townsend & Carbone, 1980). Specific considerations must be made for middle-aged and menopausal women in changing occupational roles, disease risk, familial expectations, and societal norms (Kaufert, 1996).

As we extend our understanding of menopause in both individual and institutional contexts, biological and clinical knowledge must be integrated with understanding of psychological and sociocultural factors. The menopausal experience for individual women is unique and partly shaped by her expectations and outlook. A woman’s personal experiences are also operating under large macro-forces , which dictate the societal view of menopause under social conditions and cultural outlooks.

Biomedical Model

The biomedical approach conventionally treats health conditions as purely biological events explained by specific pathways (Hyde, Nee, Howlett, Drennan, & Butler, 2010). Research on women, in particular, has been omitted and is sometimes assumed to be replicas of biological research on men (O’Donnell, Condell, & Begley, 2004). In fact, O’Donnell et al. (2004) found that having a menstrual cycle served as a confounding variable in medical research. Much of the menopausal research conducted from a biomedical perspective has treated menopause as a deficiency condition needing intervention (Hyde et al., 2010). These definitions were not only transmitted from research perspectives but also influenced masses of women and physicians.

In a deeper examination behind the biomedical construction of menopause, Niland and Lyons (2011) examined medical school textbooks from New Zealand and the United States for meanings and social indications (Niland & Lyons, 2011). The authors discovered that the selected textbooks portrayed menopause as a failure or disease, suggesting a continuation of negative connotations (ibid). These textbooks perpetuated menopause as a failure of hormone production, necessitating hormonal therapies in overt and covert language (Niland & Lyons, 2011). In an analysis of self-help brochures for women in midlife, most texts described menopause as a deficiency disease in need of management (Lyons & Griffin, 2003). These depictions made by clinicians for postmenopausal women reinforce the discourse of menopause as a problem.

Biomedical approaches segment the menopausal experience into three stages: premenopause, perimenopause, and postmenopause. Premenopause is the time period after menarche with normal fertility function, which ends with the last menstrual cycle. The perimenopause phase occurs as the last menstrual periods are approaching and may bring symptoms like irregular menstrual cycles and hormonal fluctuations (Brinton et al., 2015; Harlow et al., 2012). Finally, postmenopause is confirmed when a woman reaches the 12-month mark after her last menstrual cycle (Hoffman et al., 2016). These stages have unique implications for each woman and are not as clearly defined as medical textbooks might suggest.

Perhaps one of the most problematic consequences of the biomedical approach is the acceptance of “fixing menopause” and the subsequent medicalization of menopause (Bell, 1987; Dillaway & Burton, 2011). Menopause management, along with the management of other chronic conditions, contributed to the expansion of the pharmaceutical industry, soaring prescription drug prices, and increased drug dispensing in high-income countries (Busfield, 2010). The emergence of hormone replacement therapy is the result of a desire to remain youthful, feminine, and asymptomatic of menopause (McCrea, 1983). While the clinical distinction may be clear to physicians for diagnosis, women may not understand their current menopausal stage.

As feminists and activists normalized menopause as a natural experience not requiring biomedical intervention, new perspectives have emerged. The biomedical model limits the menopausal transition to the physical body and undermines the potentially positive experiences of individual women. An opposing view of menopause would be a continuous, lifelong perspective. In a qualitative study using in-depth interviews, Dillaway and Burton (2011) found that middle-aged women respected the biomedical definitions as a “master narrative” (Dillaway & Burton, 2011, p. 72) but usually turned to less ambiguous experiences of their mothers or female relatives. The description of menopausal symptoms is associated with negativity and inconvenience. Women found that reproductive aging was indefinite and a continuing process, not singularly defined by the final menstrual period (Dillaway & Burton, 2011). Moving beyond menopause as a deficiency, hormone therapy capitalization, and rigid definitions, the lived experiences and lives of menopausal women should be integrated with the current biomedical model .

Life Course Perspective

The life course perspective describes how individuals undergo constant development throughout their life trajectories (Elder & Rockwell, 1979). The life course perspective identifies people within their respective historical time to examine social structures and the influences on individual lives. Recent applications of the life course perspective include studies of racism, nutrition, work stress, and caregiving (Eifert, Adams, Morrison, & Strack, 2016; Gee, Walsemann, & Brondolo, 2012; Herman et al., 2014; Wahrendorf & Chandola, 2016). This theory is used to understand phenomena that impact a person throughout life, not just a singular event with little lasting significance. The life course perspective views the individual as constrained by macro social structures and influences that shift a person’s path.

As a person ages, they transition through stages such as childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and older adulthood. The life course perspective consists of five major principles : historical time and place, timing, linked lives, agency, and life span (Elder, 1998). These central constructs apply to the study of menopause over the life course of women. While the biomedical approach to menopause centered on the final menstrual period as the defining event, the life course perspective argues that menopausal transition and quality of life are results of lifelong factors and influences.

In the theory’s first principle, historical time and place, the existing societal structures within a specific time period play a major role in a woman’s experience (Elder & Rockwell, 1979). When we apply historical time and place to menopause, we consider the historical evolution of menopause management. A woman entering into her menopausal years in the 1970s will have a different experience with physician-recommended hormonal therapy as contrasted to a woman entering her menopausal years in the 1990s, when hormonal therapy was feared (McCrea, 1983). The prevalent attitudes towards menopause at a given time will greatly influence the care or lack thereof a woman may receive. The timing of menopause, the second life course principle, is defined as the life stage of menopause occurrence (Elder & Rockwell, 1979). The typical timing of menopause is in middle age and may coincide with career changes, grandparenthood, or other roles. If, however, menopause onset was unexpectedly early in a woman’s mid-30s due to natural or surgical causes, this may disrupt a woman’s reproductive plans and suddenly bring upon the premature transition into menopause. Menopause represents a turning point for women but can have very different implications on the life and trajectories of a woman set against her current stage in life .

The third life course principle is linked lives , which explains that individual experiences and historical events are interdependent and linked to the lives of shared relationships (Elder, 1998). The linked lives concept applies to menopause when a woman’s experiences are interdependent on the menopausal experiences of her mother, grandmother, friends, and community (Dillaway & Burton, 2011). A woman entering the menopausal years affects and is also affected by her interpersonal relationships. For example, if a woman living in a rural village enters menopause, her husband may be supportive and embrace sex without contraception or he may be unsupportive and even leave their marriage in extreme cases. The fourth principle of agency recognizes that individuals act and decide on their own accord within the constraints and opportunities of their circumstances (Elder, 1998). While a menopausal woman cannot control societal expectations or the reactions of her family, she has some individual agency to make decisions. A woman in the rural areas may enter a new path focusing on her business or retire to the home of her children (George, 1996). Individual women also have agency in medical therapy by deciding to take or not to take hormonal therapy in order to manage menopausal symptoms.

Finally, the life course principle of life span applies to menopause as a process that spans the entire life of the woman. This may be most clearly understood through the concept of cumulative advantage and disadvantage, when early life events shape the disparities or opportunities a person may have access to in their lifetime (Elder & Rockwell, 1979). Kaufert (1996) points out lifelong factors like malnourishment leading to anemia and obesity or lack of reproductive health care leading to cervical cancer as women age (Kaufert, 1996). Women that were disadvantaged from youth may experience deprivation throughout their lives, which may accumulate into multiple morbidities by the time they reach menopause. Cumulative disadvantage can be observed between socioeconomic status groups where women living in low- and middle-income countries tend to enter menopause at an earlier age and have less resources to mitigate menopausal symptoms as compared to women from higher income countries (Gold et al., 2001; Huddleston, Cedars, Sohn, Giudice, & Fujimoto, 2009).

Menopause is considered a significant transition for women, but under the life course perspective , menopause is a lifelong process that is not simply defined by the last menstrual period. Throughout a woman’s life, she is preparing for menopause through learned interactions from other female relatives, and health and risk factors, and entering into new life trajectories as she ages. Her experiences are also set in a historical context since culture and medical recommendations of the given time period will impact menopausal treatment. Additionally, societal expectations in peri- and postmenopause dictate physical and psychological role transitions (Kaufert, 1996). Quality of life experienced by menopausal women begins far before their last menstrual cycle but is rather associated with socioeconomic status, access to resources, and other advantages (Meleis et al., 2000). In order for the menopausal experience to be fully understood, the exploration of external environments in a woman’s trajectory must be considered.

Biopsychosocial Model

The biopsychosocial model has gained popularity in recent years within the sociology and medical fields with diverse applications in diseases, treatments, and health experiences. The prevailing version of the model was developed by Engel (1977, 1989) to expand the prevailing biomedical model and recognize that social, behavioral, and psychological factors add dimensions to health conditions (Engel, 1977; Engel, 1989). Multiple iterations of the biopsychosocial model have resulted in both reinforcing the biomedical model and developing a more holistic view of health (Pilgrim, 2015). Recent applications of the biopsychosocial model include topics as diverse as arthritis, migraines, and emotional health (Ayers, Franklin, & Ring, 2013; Renjith, Pai, Castalino, George, & Pai, 2016; Sumner & Nicassio, 2016). The similarities shared by applying the biopsychosocial model to health involve taking “the patient and his attributes as a person, a human being” (Engel, 1980, p. 2).

The biopsychosocial model integrates the individual person into a hierarchy of ongoing behavioral, psychological, and social structures (Engel, 1980). This model can be applied to menopause, simultaneously considering both the individual woman experiencing menopause and the broader systems that operate. The biomedical model focuses on the clinical manifestations of menopause while the life course perspective focuses on a woman’s experience in the context of time and her life course. The biopsychosocial model introduces a complementary viewpoint, which details the layers of menopause embedded from a micro to macro hierarchy.

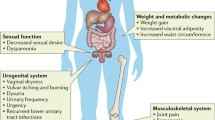

A systems approach to menopause, as posited in the biopsychosocial model, creates an ordering of the natural environment. Each level of the natural environment leads to a broader level. For example, the cells and reproductive organs comprise a full body and that individual body also comprises a family, community, and society. When applied to menopause, a woman’s hormonal fluctuations and cessation of menstruation encompass the experience of menopause. The same woman comprises a community of women also undergoing menopausal transition and she is part of the larger societal structure. In Fig. 22.1, a biopsychosocial system is represented with an individual woman undergoing menopause at the core level.

Biopsychosocial system surrounding a woman in menopause transition. Adapted from Engel (1980). The Clinical Application of the Biopsychosocial Model. American Journal of Psychiatry 137(5): 535–544

At the micro-level of the individual woman, her physical body undergoes biological processes to bring the onset of the last menstrual period from reproductive organs down to the cellular and genetic determinants. These micro factors can determine the age a woman enters menopause, level of hormonal fluctuation, and chronic disease development. While some of these factors are within the agency of the woman’s control (e.g., exposures and diet), many of the factors are predetermined (e.g., genetics and cell structure) or influenced by even larger determinants (e.g., socioeconomic status and norms). This micro hierarchy is most emphasized in the biomedical model through its focus on biochemical processes and solution with targeted therapies such as hormonal replacement.

In contrast, the macro-levels above the individual woman can range from her immediate family to broad global systems. The woman’s menopausal experiences shape her macro-level structures and vice versa. As previously discussed, cultural and social norms can dictate the woman’s changing role and symptom experience in menopause. However, the individual woman may influence her family by sharing her individual experiences with her daughter or relatives, forming a narrative within a community, and possibly influencing the larger social structure. Within the macro levels, health disparities are apparent. If an economic or a racial inequality existed at the societal level, this would negatively impact access to both overall and menopausal health care (Huddleston et al., 2009). Similarly, a woman’s beliefs for menopausal treatment, shaped by her community, will affect her decisions in seeking symptom care and types of treatments (Bell, 1990).

A complex interplay of proximal and distal factors surrounding the menopausal woman depicts the social, behavioral, and psychological underpinnings. More than one factor can be active at the same time. For example, a woman’s psychological outlook on menopause is determined by both her physiologic body experiences and the perceptions of her family and societal culture. Overall, the biopsychosocial model considers the entire system (Engel, 1989). In contrast to the biomedical model, it connects larger macrostructures. In comparison to the life course perspective, the biopsychosocial model nuances the hierarchy of these systems. The biopsychosocial model has limitations notably missing historical changes and tendency to capture defined systems while missing exploratory phenomena (Pilgrim, 2015).

Summary

For much of history, menopause was classified in negative terms as a neuroses, decline, and illness signaling a decay of purpose and life. Even in the mid-twentieth century, prominent physicians published widely read books and articles on menopause as a loss of femininity and youth. As populations of women internalized the negative discourse, a cure for menopause was sought and temporarily answered in the advent of hormone replacement therapy. The alarming health consequences that emerged from suspected hormones gave rise to a new wave of menopausal conception. Feminists and women’s health advocates began examining menopause as a natural process devoid of a medical solution. Women began to understand menopause as a positive life transition and freedom from previous expectations like childbearing.

The rise in the number of women entering into menopause and living for decades postmenopause will define clinical care and social norms in this next generation. The majority of menopause research has centered upon Caucasian women in the Western world, which limits the heterogeneity of experiences like role transitions and symptoms across countries and even within countries. Menopause has also been overwhelmingly described in biological terms, where the final menstrual period and following 12 months marks the end of menopause. Other factors that are less examined include psychological outlooks of individual women and the impact on menopause experience as well as sociocultural factors shaping the subjective norms within a woman’s society.

In theoretical applications of social constructions of menopause, we examine the biomedical model, life course perspective, and biopsychosocial model. In the biomedical model, menopause is seen as a series of biological mechanisms within the body that progress linearly and can be clearly diagnosed. This model has been widely adopted in the medical field but limits the contextualized experiences of women and institutionalized structures. The life course perspective views menopause as a lifelong process, constantly changing a woman’s individual trajectory and set against historical understandings. Disadvantages that a woman may face in her early life will not only impact her progression throughout life but also the quality of her menopause experience. The biopsychosocial model places a woman within a hierarchical system which includes both biomedical considerations at the microlevel and social structures at the macro-levels.

As the worldwide prevalence of menopause increases, health care professionals must consider a facet of individual and institutional factors when managing menopause. The experience of menopause is unique to each society, community, family, and individual woman. Menopause is associated with both negative and positive perceptions, which change with history and social norms. Further research and information capturing diverse experiences of menopause at the global level is needed to improve our knowledge of the experience. As our collective knowledge of menopause changes, the integration of lived experiences and evolving social structures must also accompany the menopausal dialogue.

Discussion Questions

-

1.

Given the complex history of menopause, what types of structures allow prominent physicians and activists to influence entire societies and individual women?

-

2.

As the number of women entering menopause and living longer in postmenopause increases globally, what factors do you think have been thus far overlooked?

-

3.

When thinking about the life course perspective and menopause as a lifelong process, what types of psychological and sociocultural factors influence a woman throughout her youth and into her menopause years?

-

4.

How does the life course perspective and biopsychosocial model differ from the biomedical model? What similarities still exist?

-

5.

Would you prefer applying the life course perspective or the biopsychosocial model to menopause? What is your reasoning?

References

Avis, N. E., Stellato, R., Crawford, S., Bromberger, J., Ganz, P., Cain, V., & Kagawa-Singer, M. (2001). Is there a menopausal syndrome? Menopausal status and symptoms across racial/ethnic groups. Social Science & Medicine, 52(3), 345–356. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00147-7.

Avis, N. E., Brockwell, S., Randolph, J. F., Shen, S., Cain, V. S., Ory, M., & Greendale, G. A. (2009). Longitudinal changes in sexual functioning as women transition through menopause: Results from the study of women’s health across the nation (SWAN). Menopause, 16(3), 442–452. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e3181948dd0.

Ayers, B., Forshaw, M., & Hunter, M. S. (2010). The impact of attitudes towards the menopause on women’s symptom experience: A systematic review. Maturitas, 65(1), 28–36. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.10.016.

Ayers, D. C., Franklin, P. D., & Ring, D. C. (2013). The role of emotional health in functional outcomes after orthopaedic surgery: Extending the biopsychosocial model to orthopaedics: AOA critical issues. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume, 95(21), e165. doi:10.2106/jbjs.l.00799.

Bani, S., Hasanpour, S., Farzad Rik, L., Hasankhani, H., & Sharami, S. H. (2013). The effect of folic acid on menopausal hot flashes: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Caring Sciences, 2(2), 131–140. doi:10.5681/jcs.2013.016.

Barnabei, V. M. (2007). Making the diagnosis. In R. Wang-Cheng, J. M. Neuner, & V. M. Barnabei (Eds.), Menopause (p. 212). Philadelphia, PA: The American College of Physicians.

Bell, S. E. (1987). Changing ideas: The medicalization of menopause. Social Science & Medicine, 24(6), 535–542.

Bell, S. E. (1990). Sociological perspectives on the medicalization of menopause. Annals of Human Biology, 592, 173–178.

Benedek, T. (1973). Psychoanalytic investigations: selected papers. New York: Quandrangle [i.e. Quadrangle.

Boulet, M. J., Oddens, B. J., Lehertb, P., Vemer, H. M., & Visser, A. (1994). Climacteric and menopuase in seven south-east Asian countries. Maturitas Journal of the Climacteric & Postmenopause, 19, 157–176.

Brinton, R. D., Gore, A. C., Schmidt, P. J., & Morrison, J. H. (2009). 68—reproductive aging of females: Neural systems A2—Pfaff, Donald W. In A. P. Arnold, A. M. Etgen, S. E. Fahrbach, & R. T. Rubin (Eds.), Hormones, brain and behavior (2nd ed., pp. 2199–2224). San Diego: Academic Press.

Brinton, R. D., Yao, J., Yin, F., Mack, W. J., & Cadenas, E. (2015). Perimenopause as a neurological transition state. Nature Reviews. Endocrinology, 11(7), 393–405. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2015.82.

Busfield, J. (2010). ‘A pill for every ill’: Explaining the expansion in medicine use. Social Science & Medicine, 70(6), 934–941. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.068.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2016). World population by age and sex. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/population/international/data/worldpop/tool_population.php.

Dalal, P. K., & Agarwal, M. (2015). Postmenopausal syndrome. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 57(Suppl 2), S222–S232. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.161483.

Dennerstein, L., Dudley, E., & Burger, H. (2001). Are changes in sexual functioning during midlife due to aging or menopause? Fertility and Sterility, 76(3), 456–460.

Dillaway, H. E., & Burton, J. (2011). “Not done yet?!” Women discuss the “end” of menopause. Women’s Studies, 40(2), 149–176.

Eifert, E. K., Adams, R., Morrison, S., & Strack, R. (2016). Emerging trends in family caregiving using the life course perspective: Preparing health educators for an aging society. American Journal of Health Education, 47(3), 176–197. doi:10.1080/19325037.2016.1158674.

Elder, G. H., Jr. (1998). The life course as developmental theory. Child Development, 69(1), 1–12.

Elder, G. H., Jr., & Rockwell, R. C. (1979). The life-course and human development: An ecological perspective. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 2, 1–21.

Engel, G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129–136.

Engel, G. L. (1980). The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 137(5), 535–544.

Engel, G. L. (1989). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Holistic Medicine, 4(1), 37–53.

Foxcroft, L. (2010). Hot flushes, cold science: A history of the modern menopause. London: Granta.

Gee, G. C., Walsemann, K. M., & Brondolo, E. (2012). A life course perspective on how racism may be related to health inequities. American Journal of Public Health, 102(5), 967–974. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300666.

George, T. (1996). Women in a south Indian fishing village: Role identity, continuity, and the experience of menopause. Health Care for Women International, 17(4), 271–279. doi:10.1080/07399339609516244.

Gold, E. B., Bromberger, J., Crawford, S., Samuels, S., Greendale, G. A., Harlow, S. D., & Skurnick, J. (2001). Factors associated with age at natural menopause in a multiethnic sample of midlife women. American Journal of Epidemiology, 153(9), 865–874.

Grisso, J. A., Freeman, E. W., Maurin, E., Garcia-Espana, B., & Berlin, J. A. (1999). Racial differences in menopause information and the experience of hot flashes. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 14(2), 98–103.

Harlow, S. D., Gass, M., Hall, J. E., Lobo, R., Maki, P., Rebar, R. W., … de Villiers, T. J. (2012). Executive summary of the stages of reproductive aging workshop + 10: Addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. Menopause, 19(4), 387–395. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e31824d8f40.

Herman, D. R., Taylor Baer, M., Adams, E., Cunningham-Sabo, L., Duran, N., Johnson, D. B., & Yakes, E. (2014). Life course perspective: Evidence for the role of nutrition. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 18(2), 450–461. doi:10.1007/s10995-013-1280-3.

Hickey, M., Ambekar, M., & Hammond, I. (2010). Should the ovaries be removed or retained at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease? Human Reproduction Update, 16(2), 131–141. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmp037.

Hoffman, B. L., Schorge, J. O., Bradshaw, K. D., Halvorson, L. M., Schaffer, J. I., & Corton, M. M. (2016). Williams gynecology (3rd ed., pp. 471–491). New York: McGraw-Hill Education/Medical.

Huddleston, H. G., Cedars, M. I., Sohn, S. H., Giudice, L. C., & Fujimoto, V. Y. (2009). Racial and ethnic disparities in reproductive endocrinology and infertility. Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility, 2010, 413–419.

Huss, K. S. (1966). Feminine forever. JAMA, 197(2), 156.

Hyde, A., Nee, J., Howlett, E., Drennan, J., & Butler, M. (2010). Menopause narratives: The interplay of women’s embodied experiences with biomedical discourses. Qualitative Health Research, 20(6), 805–815. doi:10.1177/1049732310363126.

International Menopause Society. (2016). Menopause terminology. Retrieved November 4, 2016, from http://www.imsociety.org/menopause_terminology.php.

Joffe, H., Guthrie, K. A., LaCroix, A. Z., Reed, S. D., Ensrud, K. E., Manson, J. E., … Cohen, L. (2014). Randomized controlled trial of low-dose estradiol and the SNRI venlafaxine for vasomotor symptoms. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(7), 1058–1066. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1891.

Jones, E. K., Jurgenson, J. R., Katzenellenbogen, J. M., & Thompson, S. C. (2012). Menopause and the influence of culture: Another gap for Indigenous Australian women? BMC Womens Health, 12, 43. doi:10.1186/1472-6874-12-43.

Kaufert, P. A. (1996). The social and cultural context of menopause. Maturitas Journal of the Climacteric & Postmenopause, 23, 169–180.

Kwawukume, E. Y., Ghosh, T. S., & Wilson, J. B. (1993). Menopausal age of Ghanaian women. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 40(2), 151–155.

Laan, E., & Lunsen, R. H. W. V. (2009). Hormones and sexuality in postmenopausal women: A psychophysiological study. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology, 188(2), 126–133.

Lee, K. H. (1997). Korean urban women’s experience of menopause: New life. Heatlh Care for Women International, 18, 139–148.

Leiblum, S. R., Koochaki, P. E., Rodenberg, C. A., Barton, I. P., & Rosen, R. C. (2006). Hypoactive sexual desire disorder in postmenopausal women: US results from the women’s international study of health and sexuality (WISHeS). Menopause: The Journal of the North American Menopause Society, 13(1), 46–56.

Lonnèe-Hoffmann, R. A. M., Dennerstein, L., Lehert, P., & Szoeke, C. (2014). Sexual function in the late postmenopause: A decade of follow-up in a population-based cohort of Australian women. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 11(8), 2029–2038. doi:10.1111/jsm.12590.

Lyons, A. C., & Griffin, C. (2003). Managing menopause: A qualitative analysis of self-help literature for women at midlife. Social Science & Medicine, 56(8), 1629–1642.

McCrea, F. B. (1983). The politics of menopause: The “discovery” of a deficiency disease. Social Problems, 31(1), 111–123. doi:10.2307/800413.

Meleis, A. I., Sawyer, L. M., Im, E.-O., Hilfinger Messias, D. K., & Schumacher, K. (2000). Experiencing transitions: An emerging middle-range theory. Advances in Nursing Sciencee, 23(1), 12–28.

National Institute on Aging. (2013). Menopause. https://www.nia.nih.gov/sites/default/files/menopause_2.pdf.

Niland, P., & Lyons, A. C. (2011). Uncertainty in medicine: Meanings of menopause and hormone replacement therapy in medical textbooks. Social Science & Medicine, 73(8), 1238–1245. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.07.024.

O’Donnell, S., Condell, S., & Begley, C. M. (2004). ‘Add women & stir’—The biomedical approach to cardiac research! European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 3(2), 119–127. doi:10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2004.01.003.

Obermeyer, C. M. (2000). Menopause across cultures: A review of the evidence. Menopause, 7(3), 184–192.

OlaOlorun, F. M., & Lawoyin, T. O. (2009). Experience of menopausal symptoms by women in an urban community in Ibadan, Nigeria. Menopause, 16(4), 822–830.

Osarenren, N., Ubangha, M. B., Nwadinigwe, I. P., & Ogunleye, T. (2009). Attitudes of women to menopause: Implications for counselling. Edo Journal of Counseling, 2(2), 155–164.

Pilgrim, D. (2015). The biopsychosocial model in health research: Its strengths and limitations for critical realists. Journal of Critical Realism, 14(2), 164–180.

Rahn, D. D., Ward, R. M., Sanses, T. V., Carberry, C., Mamik, M. M., Meriwether, K. V., … Murphy, M. (2015). Vaginal estrogen use in postmenopausal women with pelvic floor disorders: Systematic review and practice guidelines. International Urogynecology Journal, 26(1), 3–13. doi:10.1007/s00192-014-2554-z.

Renjith, V., Pai, M. S., Castalino, F., George, A., & Pai, A. (2016). Engel’s model as a conceptual framework in nursing research: Well-being and disability of patients with migraine. Holistic Nursing Practice, 30(2), 96–101. doi:10.1097/hnp.0000000000000136.

Ringa, V. (2000). Menopause and treatments. Quality of Life Research, 9(1), 695–707. doi:10.1023/a:1008913605129.

Saag, K. G., & Geusens, P. (2009). Progress in osteoporosis and fracture prevention: Focus on postmenopausal women. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 11(5), 251–251. doi:10.1186/ar2815.

Schoenaker, D. A., Jackson, C. A., Rowlands, J. V., & Mishra, G. D. (2014). Socioeconomic position, lifestyle factors and age at natural menopause: A systematic review and meta-analyses of studies across six continents. International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(5), 1542–1562. doi:10.1093/ije/dyu094.

Sharifi, K., Anoosheh, M., Foroughan, M., & Kazemnejad, A. (2014). Barriers to middle-aged women’s mental health: A qualitative study. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 16(6), e18882. doi:10.5812/ircmj.18882.

Shifren, J. L., & Gass, M. L. (2014). The North American Menopause Society recommendations for clinical care of midlife women. Menopause, 21(10), 1038–1062. doi:10.1097/gme.0000000000000319.

Spira, M., & Berger, B. (1999). The evolution of understanding menopause in clinical treatment. Clinical Social Work Journal, 27(3), 259–273. doi:10.1023/a:1022890219316.

Sumner, L. A., & Nicassio, P. M. (2016). The importance of the biopsychosocial model for understanding the adjustment to arthritis. In P. M. Nicassio (Ed.), Psychosocial factors in arthritis: Perspectives on adjustment and management (pp. 3–20). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Townsend, J. M., & Carbone, C. L. (1980). Menopausal syndrome: Illness or social role - a transcultural analysis. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 4, 229–248.

Utian, W. H. (1997). Menopause—A modern perspective from a controversial history. Maturitas, 26(2), 73–82. doi:10.1016/S0378-5122(96)01092-4.

Voda, A. M., & Ashton, C. A. (2006). Fallout from the women’s health study: A short-lived vindication for feminists and the resurrection of hormone therapies. Sex Roles, 54(5), 401–411. doi:10.1007/s11199-006-9010-6.

Wahrendorf, M., & Chandola, T. (2016). A life course perspective on work stress and health. In J. Siegrist & M. Wahrendorf (Eds.), Work stress and health in a globalized economy: The model of effort-reward imbalance (pp. 43–66). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

WHO. (2015). World report on ageing and health. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

Wilson, R. A. (1968). Feminine forever (1st ed.). New York: Pocket Books.

Suggested Reading

Dillaway, H. E., & Burton, J. (2011). “Not done yet?!” Women discuss the “end” of menopause. Women's Studies, 40(2), 149–176.

Foxcroft, L. (2010). Hot flushes, cold science: A history of the modern menopause. London, UK: Granta.

Niland, P., & Lyons, A. C. (2011). Uncertainty in medicine: Meanings of menopause and hormone replacement therapy in medical textbooks. Social Science & Medicine, 73(8), 1238–1245.

Schoenaker, D. A., Jackson, C. A., Rowlands, J. V., & Mishra, G. D. (2014). Socioeconomic position, lifestyle factors and age at natural menopause: a systematic review and meta-analyses of studies across six continents. International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(5), 1542–1562.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Yisma, E., Ly, S. (2018). Menopause: A Contextualized Experience Across Social Structures. In: Choudhury, S., Erausquin, J., Withers, M. (eds) Global Perspectives on Women's Sexual and Reproductive Health Across the Lifecourse. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60417-6_22

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60417-6_22

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-60416-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-60417-6

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)