Abstract

The aim of this paper is to analyze and classify research that has been conducted on manufacturing reshoring, i.e., the decision to bring back to the home country production activities earlier offshored, independently of the governance mode (insourcing vs. outsourcing). Literature reviews proposed until now usually paid almost exclusive attention to motivations driving this phenomenon. This paper offers a broader and more comprehensive examination of the extant knowledge of manufactiring reshoring and identifies the main unresolved issues and knowledge gaps, which future research should investigate. Moreover, the purpose of the paper is to provide avenues for future research and highlight the distinct value of studying manufacturing reshoring either per se or in combination with other constructs of the international business tradition. A set of 49 carefully selected articles on manufacturing reshoring published in international journals or books indexed on Scopus in the last 10 years is systematically analyzed based on the “5 Ws and 1H” (Who-What-Where-When-Why and How) set of questions. Our work shows a certain convergence among authors regarding what reshoring is, what its key features and motivations are. In contrast, other related aspects, such as the decision making and implementation processes, are comparatively less understood.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

In the last few years, both large multinational companies and small enterprises operating in different industries have decided to (at least partially) reverse their previous manufacturing offshoring decisions and have brought their production activities back home. This phenomenon has often been referred to as manufacturing reshoring, although other terms have been used as well (e.g., backshoring, back-sourcing). In this paper, we prefer to use the term manufacturing reshoring since it is the most diffused among scholars and practitioners. However, we note that this term is often adopted to indicate different concepts.Footnote 1

Interest in manufacturing reshoring rose initially among practitioners; more recently it has gained momentum among scholars (Fratocchi et al. 2015, 2016; Stentoft et al. 2016b) and policy makers (De Backer et al. 2016; European Parliament Resolution 2014; Guenther 2012; Livesey 2012; The White House 2012). In light of the rapidly increasing amount of publications on the topic, literature reviews have been recently conducted, though they have only been taking into account the motivations driving the phenomenon (Foerstl et al. 2016; Stentoft et al. 2016b). A broader and more “comprehensive” examination of the extant knowledge of reshoring is currently missing. Accordingly, this paper offers a structured literature review of the manufacturing reshoring phenomenon. It provides a state-of-the-art of what reshoring is, how it is characterized in terms of firms’ elements (e.g., size, industry), countries (host/home), industries and time-related elements, and why and how it is planned and implemented. From that, the paper aims to identify the main unresolved issues and knowledge gaps, which future research should investigate.

Similar to previous literature reviews (e.g., Mugurusi and de Boer 2013, on offshoring), we structure our work around the issues of the what-who-why-where-when and how of reshoring (i.e., “The 5 W and 1H” of reshoring). In so doing, we take a firm-level outlook with specific attention given to the reshoring of manufacturing activities. Therefore, we exclude reshoring decisions implemented by service companies, since the two phenomena need a different approach (Albertoni et al. 2017). Within manufacturing companies, we focus only on production activities, excluding the relocation of other value chain activities (e.g., R&D). In that, we follow Benito et al. (2009) suggestion to choose specific value chain activities (rather than the whole chain) as the unit of analysis. Finally, we consider both insourced and outsourced manufacturing activities as being location decisions separate from the governance mode ones (Gray et al. 2013).

Our work shows a certain convergence among authors regarding what reshoring is and what its key features are. It brings evidence that reshoring can be characterized as either a reaction to (internal and external) changes, or a correction of previous managerial mistakes. Interestingly, our analysis suggests that other related aspects, such as decision making and the implementation processes of reshoring, are comparatively less understood.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the methodology adopted to implement the literature review. Section 3 reviews the extant literature adopting the what-who-why-where-when and how approach. Section 4 discusses unresolved issues and ideas for future research.

2 Methodology

The main aim and contribution of this paper is to synthesize and systematize the extant literature on manufacturing reshoring. A structured literature review is “a systematic, explicit, and reproducible design for identifying, evaluating, and interpreting the existing body of recorded documents” (Fink 2005, p. 6). We adopted the Seuring and Gold (2012) process model for content analysis based on four main steps. The first step is “material collection”; in this regard, we focused our attention on indexed articles published in academic journals and chapters in scientific books. Documents were identified by searching in the “Elsevier Scopus” database, which is recognized as one of the top business and management databases (Greenwood 2011). All documents published until 2016 December 31 were considered. The search terms “reshoring”, “re-shoring”, “backshoring”, “back-shoring”, “back-reshoring” and “back-sourcing” were checked in title, abstract and keywords. We found a total of 70 documents (including duplications) whose abstracts were read by two of the co-authors. After this, the following exclusion criteria were implemented: (a) duplications; (b) papers written in languages other than English; (c) papers focusing on the reshoring of firm’s activities differently from manufacturing ones (for instance, call centers). The final list of documents included in the systematic literature review consisted of 49 documents (45 journal articles and four book chapters) published from 2007 to 2016 (Fig. 1).

The second step of the Seuring and Gold (2012) process model concerns descriptive analysis, which is an assessment of the formal characteristics of the chosen documents. In this regard, the data summarized in Fig. 1 show that the interest of scholars has considerably increased since 2013. As for the journals, among the 45 peer-reviewed articles, we found almost half of articles to belong to operation management or supply chain management, and surprisingly, IB and business strategy journals were much less represented (Table 1).

The third step of our analysis was category selection, i.e., to define analytical categories to classify documents’ contents. To critically review the selected literature, we adopt six questions considered useful to describe phenomena, namely what-who-when-where-why and how. More specifically the questions examine the following issues:

-

(a)

What: This question stems from Gray et al. advice to define “what [reshoring] is and what it is not” (2013, p. 29), i.e., to define the phenomenon and to characterize it in terms of its essential features. Therefore, we verify the (eventual) convergence among scholars with regard to proposed reshoring concepts.

-

(b)

Who: This question focuses on the characteristics of the firms implementing reshoring strategies. It aims to provide a more meaningful picture of the phenomenon by investigating whether firms’ propensity to reshore depends on factors such as their size and industry.

-

(c)

Why: This question refers to the motivations that induce companies to reshore production in their home countries.

-

(d)

How: This question essentially relates to the decision-making and implementation phases of reshoring strategies, i.e., how managers make decisions to repatriate offshored activities and how they put these decisions into practice.

-

(e)

Where: This question is related to the geographical aspect and is evaluated at both the home and host country levels.

-

(f)

When: This question is mainly focused on the duration of the offshore experience and the (possible) impact of the occurrence of contingent factors, such as the global economic crisis.

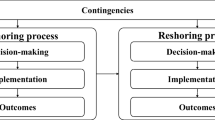

Figure 2 summarizes topics addressed in each article showing the “How” question is comparably less analyzed.

With respect to the Where question, breakdown by home country shows data at worldwide level are scarce (Table 2).

The final step of Seuring and Gold’s (2012) process model for content analysis is regarding material evaluation. This activity was performed by reading, analyzing and coding all selected documents with the 5Ws and 1H questions in focus. The process reliability was improved by discussion within the research team (researcher triangulation) and by ensuring process documentation (Denyer and Tranfield 2009).

3 The Extant Literature

3.1 The “What” of Reshoring

A certain number of definitions of “What” reshoring can be found in the literature (Table 3). We see also how authors sometimes use the same term (for instance, reshoring) to indicate different concepts. Generally, dissimilarities among the various definitions of reshoring can be mainly found regarding the following aspects.

-

(a)

Country in which earlier offshored manufacturing activities are reshored: some authors (Arlbjørn and Lüthje 2012; Ashby 2016; Bals et al. 2016; Ellram et al. 2013) referred to production activities being moved to both the home country and those “near the home country”. To avoid such a possible confusion, some authors suggested distinguishing between back-(re)shoring (Bals et al. 2016; Foerstl et al. 2016; Fratocchi et al. 2014a, b), which is when the production transfer is directed toward the home country, and near-(re)shoring (Bals et al. 2016; Foerstl et al. 2016; Fratocchi et al. 2014a, b), if it is oriented toward countries close to the home country.

-

(b)

Types of relocated activities: while the majority of analyzed papers are focused on production activities, some of them broadly refer to Porter’s value chain activities (Bals et al. 2016; Zhai et al. 2016), “activities or functions” (Gylling et al. 2015) and “firms’ foreign activities” (Stentoft et al. 2016a).

-

(c)

Governance structure adopted in the manufacturing offshoring and reshoring phases: some authors maintained that reshoring strategies imply contextual insourcing decisions (see, among others: Ellram et al. 2013; Lam and Khare 2016; Uluskan et al. 2016). Arlbjørn and Mikkelsen (2014) acknowledged that decisions about governance mode are conceptually independent of locational decisions, but they can be practically combined with the reshoring decision. More recently, Bals et al. (2016) state that reshoring and insourcing are “interconnected” decisions.

Some scholars suggest that while reshoring is essentially a manufacturing location decision, it can actually take different forms. Accordingly, they propose classifications to specialize the characteristics of different reshoring forms. For instance, Gray et al. (2013) identified four alternate typologies of reshoring based on a combination of location decision (home vs. host country) and governance mode (insourcing vs. outsourcing). More recently, Bals et al. (2016) and Foerstl et al. (2016) enlarged this classification to include the cooperation alternative (e.g., joint ventures, strategic partnerships and long-term contracts) among the governance modes, thus identifying six alternatives, including the four proposed by Gray et al. (2013).

Zhai et al. (2016) propose differentiating reshoring decisions according the target markets for products manufactured offshore; more specifically, they consider the following alternatives: home market, host market and regions around the home market. Based on such a classification, the authors show that manufacturing reshoring decisions implemented by US companies are addressed almost exclusively to goods to be sold in the home market.

Finally, Joubioux and Vanpoucke (2016), based on Bellego (2014), propose to differentiate the reshoring phenomenon according the strategic aims of such firm’s decisions identifying the following alternatives: (a) “home re-shoring”, in case of failure of earlier offshoring decision; (b) “tactical reshoring”, for short term decisions based on availability of resource and capabilities; (c) “development reshoring”, if the firm’s aims is to upgrade the proposed products.

3.2 The “Who” of Reshoring

The “Who” question inquires whether differences in manufacturing reshoring patterns are observed among different types of firms features, like size and industry.

When it comes to size, the findings differ among different studies. While Kinkel (2014), and Kinkel and Maloca (2009) stated that manufacturing reshoring hardly occurs among small and medium enterprises (SMEs, having fewer than 250 employees), Canham and Hamilton (2013) found a higher propensity to production repatriation of such firms with respect to large ones. Both these studies are focused on a single home country, therefore the findings may be influenced by the characteristics of these economies. Fratocchi et al. (2016), whose dataset spans multiple home countries, in fact showed that reshoring is only slightly more diffused among large firms. They also noted differences according to the home country location for SMEs; specifically, while SMEs headquartered in North America constituted the majority of sampled firms, Western European SMEs represented only one third of the total amount. Overall, preliminary evidence seems to suggest that reshoring happens for both large and small companies; however, Ancarani et al. (2015) found that SMEs generally repatriated their production activities earlier compared to large ones.

With regard to the industry, the extant literature has clearly shown that reshoring strategies were implemented in a broad set of manufacturing sectors (Table 4): as such, potentially reshoring is of interest to a very large number of companies. The scarcity of quantitative research prevents any conclusive outcome regarding how industry-specific characteristics may impact the firm’s propensity to reshore. However, Kinkel (2014) found that German machinery and equipment manufacturers were generally more active in reshoring, compared to firms in other industries. Based on this finding, the author speculated that high complexity, extreme product customization and small batch sizes led to a (comparatively) greater propensity to reshore, as was the case for machinery and equipment producers.

At a more general level, Fratocchi et al. (2015) did not observe any difference in the reshoring frequency between labor—and capital-intensive industries.

3.3 The “Why” of Reshoring

The “Why” of reshoring concerns the motivations that induce companies to reshore their production activities that were earlier offshored. Therefore, it is not surprising that identification and analysis of the reasons “Why” firms decide to repatriate manufacturing activities are also among the most common topics in reshoring studies, and a vast and varied array of motivations have been identified by scholars (for up-to-date literature reviews, see Bals et al. 2016; Fratocchi et al. 2016; Stentoft et al. 2016b).

While the vast array of motivations identified in the literature suggest that reshoring decisions can originate for several reasons, some authors (e.g., Bals et al. 2016) have argued they can be ultimately intended as either a deliberate strategy or a reaction to offshoring failure. This “dual view” of reshoring combines two different interpretations of reshoring proposed in the extant literature, i.e., either a mere correction of a prior misjudged decision (Gray et al. 2013; Kinkel and Maloca 2009) or a deliberate response to exogenous or endogenous changes (Fratocchi et al. 2015; Gylling et al. 2015; Martínez-Mora and Merino 2014; Mugurusi and de Boer 2013). Among the latter group, Grandinetti and Tabacco (2015) specifically referred to changes in a firm’s business strategy consistent with the idea that reshoring is “more than just a geographical shift of operations. It is also a reconfiguration of systems” (Mugurusi and de Boer 2014, p. 275). In this respect, it must be noted that while manufacturing offshoring decisions are often motivated by cost elements (especially the labor ones) (Schmeisser 2013), reshoring strategies seem to be undertaken also on the base of strategic elements, such as “made in effect”, vicinity among R&D, engineering and production, responsiveness to customer demand.

Based on the earlier discussion, it seems useful to propose a classification of the large amount of manufacturing reshoring motivations found in the sampled literature. More specifically, we suggest categorizing drivers according to a three-step approach:

-

(a)

following the suggestion by Bals et al. (2016), we separate motivations belonging to the conceptualization of reshoring as a “managerial mistake” from those related to a strategic decision;

-

(b)

the latter category (strategic decision) was further divided according to the internal and external environment, following the suggestion of Fratocchi et al. (2016);

-

(c)

since the amount of internal and external motivations is still considerable, we further divided the two arrays according to motivations homogeneity, taking into account the categories proposed by Stentoft et al. (2016b), and Fratocchi et al. (2015).

The five drivers belonging to the “managerial mistake” category (Table 5) were found in ten (out of 49 analyzed) articles. Among them, the most relevant was “Miscalculation of actual cost and/or Adoption of new cost accounting methods”, such as Total Cost of Ownership. Once more, this finding is interesting since offshoring decisions were often based on efficiency claims (Schmeisser 2013).

Drivers belonging to the “external environment” category were intensively discussed in the extant literature; therefore, they were found in 31 (out of 49) articles or book chapters (Table 6). The 32 motivations were classified into seven homogeneous categories, of which “Costs” was the most relevant in terms of both number of drivers and total citations. The three most cited single motivations were “Poor level quality of offshored manufactured products” (belonging to the “Customer related issues”), “Production and delivery time impact” (“Supply chain management” category) and “Reduction of labor cost gap between the host and home country” (Costs category). This seems to confirm the idea that manufacturing reshoring strategies have a complex nature and are not based only on efficiency issues.

Finally, the 18 reshoring drivers belonging to the “internal environment” category were addressed by 35 authors (out of 49) (Table 7). Among them, a specific attention should be paid to the strategic motivations (“Change in firm’s business strategy (e.g., new business area, vertical integration)” and sustainability issues (“Firm’s aims in terms of environmental and social sustainability”).

To sum up, reasons driving reshoring decisions are now reasonably well known, although the paucity of large-scale empirical investigations prevents any definitive conclusions being drawn about their actual and relative magnitude, as well as their relevance for companies.

3.4 The “How” of Reshoring

Although the decision-making and implementation process of reshoring (i.e., “How” firms decide to reshore and “How” they put that into practice) is a key aspect for a comprehensive study of the phenomenon, to date the topic has been covered only by a limited number of contributions (Table 4).

In order to manage the decision making process phase, both Mugurusi and De Boer (2014), and Bals et al. (2016) propose models articulated in a set of actions. More specifically, Mugurusi and De Boer (2014) suggest adopting a Viable System Model (VSM) approach (Beer 1972), which conceptualizes the firm as “a dynamic adaptive system in search of ways to cope effectively with external forces that undermine its viability” (Mugurusi and de Boer 2014, p. 275), i.e., the firm’s ability to exist independently (Beer 1984). In other words, reshoring “serves to increase the stability of the system” (Mugurusi and de Boer 2014, p. 289), giving it a new configuration. To reach such an objective, the firm has to follow a four-step process, the first of which is to design the ex-ante VSM firm’s map, which is the description of the five systems that form the company and interconnections among them. Afterwards, reshoring motivations should be identified and analyzed and the ex post (i.e., after reshoring decision implementation) VSM firm’s map designed. On the basis of such activities, managers may eventually take the decision to reshore and implement it. After this, they should carefully monitor the performance of the reshored manufacturing activities.

Bals et al. (2016) observe that despite the question of how to reconfigure supply chains is quite a relevant issue for both scholars and managers to understand, the decision making and implementation of reshoring and insourcing remain largely unexplored. They build on established sourcing decision making processes (Handley 2012; McIvor 2010) and offshoring implementation processes (Jensen et al. 2013) to provide a conceptual framework for how reshoring (and/or insourcing) decisions should be taken and implemented. Specifically, the decision making framework consists of five steps—spanning from the characterization of the current firm’s boundary, capabilities, and performance, to the collection of alternatives, data analysis and solution development, and eventually to the shoring decision. As for the following implementation framework, it includes the three phases of disintegration at the former location, relocation to the new location, and reintegration to connect with other value-creation activities. Beyond the specification of the framework structure, Bals et al. (2016) highlight the key aspects and issues that must be properly understood to make each phase effective. Among them, the assessment of organizational readiness—i.e., the firm’s ability to handle the outcomes of their decision—is crucial to the identification of alternatives, and their effective analysis. As for the implementation phase, the authors suggest the importance of organizational learning from previous reshoring experience; likewise for offshoring decisions, “successful past implementation of such decisions provides a feedback loop into future decision making process” (Bals et al. 2016, p. 11).

3.5 The “Where” of Reshoring

The “Where” question refers to the key geographical characteristics of manufacturing reshoring, i.e., the home and host countries. Both elements have been investigated on the basis of surveys focused on only a very few geographical areas.

To the best of our knowledge, the most complete analysis conducted to date is the “Innovation on Production” survey of German companies (Kinkel 2012, 2014; Kinkel and Maloca 2009). Because this study is performed every two years, it offers longitudinal trends in the reshoring behavior of German companies belonging to different sectors. Kinkel (2014), commenting on the results of the 15-year research on German reshoring practices, indicated that manufacturing reshoring is a relevant phenomenon. More specifically, approximately 400–700 German companies have implemented such decisions, although the share of companies relocating back to Germany earlier after having offshored production has been decreasing since the beginning of the new century.

Tate et al. (2014) used a survey-based approach to investigate the perceptions of US managers on the past and projected trends of factors influencing (re)location decisions. More recently, Zhai et al. (2016) observed that the reshoring strategies of US companies have not been heavily investigated.

Canham and Hamilton conducted a survey regarding New Zealand SMEs operating in consumer and industrial goods. They found reshoring “occurs when lower labour costs become offset by impaired capabilities in flexibility/delivery; quality; and the value of the Made in New Zealand brand” (2013, p. 277). They also found that such motivations were similar to those cited by companies who had decided never to offshore their production activities.

Finally, data regarding several countries at the worldwide level (Ancarani et al. 2015; Fratocchi et al. 2014b, 2015, 2016) reveal that reshoring decisions are implemented mainly from China and other Asian countries.

3.6 The “When” of Reshoring

The “When” question refers to the time-related aspects of reshoring. Up to now, only two studies have dealt with this issue by analyzing: (a) the duration of offshore manufacturing experience prior to reshoring (Ancarani et al. 2015); and (b) the occurrence of reshoring after the global financial crisis in 2008–2009 (Kinkel 2012, 2014).

With regard to the duration aspect, Ancarani et al. (2015), by adopting a survival analysis approach, were able to investigate the determinants of time span in a sample of companies belonging to several countries, mainly in the EU and US. Their findings revealed that the duration seemed to be influenced by several of the elements that we analyzed in the previous sections, such as firm size, industry, reshoring mode relative to governance structure, motivations, and host country.

Regarding the eventual impact of the global financial crisis on the reshoring phenomenon, Kinkel (2012) found that, while offshoring decisions implemented by German companies decreased over the course of the global economic crisis, the companies that did relocate were generally stable. In contrast, Fratocchi et al. (2015) reported that reshoring has grown significantly in the last few years, boosted by the return of North American firms.

4 Concluding Remarks: Where Reshoring Research Stands Now and Where It Might Go

It is our belief that the main contribution of the structured literature review we conducted is to provide the reader with a meaningful picture of the state-of-the-art of reshoring. Particularly, our work integrates and expands previous overviews of this rising phenomenon (e.g., Foerstl et al. 2016; Stentoft et al. 2016b) by undertaking a far broader perspective of the investigation. In addition, the outcome of a research approach such as the one we adopted—i.e., conducted through the lens of the six questions (5Ws & 1H)—offers a basically thorough rigorous starting point for future research efforts which could either explore any of them more in depth, or combine the different research questions for more elaborated investigations. Consistent with this idea, we make a first attempt to highlight possible avenues of research to enhance the understanding of reshoring.

With regard to the “What” question, a certain consensus has apparently been reached regarding many of its distinctive features—although as noted, a few of them remain debated. Further research is needed to characterize better the “object” of reshoring in terms of the characteristics of the manufacturing activities that are brought back (e.g., task complexity, degree of knowledge codifiability and types of required skills). However, the most relevant unresolved issues are regarding the relationship between offshoring and reshoring phenomena. In this respect, we share the idea of Joubioux and Vanpoucke (2016) that two such firms’ decisions are strictly interconnected. Therefore, future studies should carefully analyze the similarities and differences between the two phenomena, especially in terms of motivation and decision-making processes. In this way, it will be possible to characterize and better explain how companies may optimize their global manufacturing footprints (Stentoft et al. 2016b).

The “Why” of reshoring is definitely one the most investigated questions in the literature. However, some technical/technological aspects—such as the roles of disruptive manufacturing technologies (see for instance, Foster 2016), automation (Arlbjørn and Mikkelsen 2014; Baldwin and Venables 2013; Stentoft et al. 2016b) and additive manufacturing—seem still to be scarcely investigated. At the same time, as reshoring decisions are a complex entanglement of motivations, specific attention should be paid to (eventual) interdependences among motivations (i.e., in terms of time, proximity, consumer response, risks, innovation). Finally, motivations and their (eventual interdependencies) should be investigated by coupling them with the governance mode alternatives (insourcing and outsourcing).

The “How” question is clearly an under-investigated topic, perhaps because of the novelty of the phenomenon, which reduces the possibility of implementing longitudinal studies (Fratocchi et al. 2015) that are still scarce (Ashby 2016; Gylling et al. 2015; Robinson and Hsieh 2016). Future research should focus on how organizations should support reshoring strategies, for instance in terms of organizational readiness and willingness (Bals et al. 2016), access to competence (Stentoft et al. 2016b), learning and dynamic capabilities (Arlbjørn and Lüthje 2012; Bals et al. 2016; Kinkel 2014) and decision-making processes (Bals et al. 2016; Gylling et al. 2015; Joubioux and Vanpoucke 2016; Stentoft et al. 2016b).

Regarding the “When” question, the duration aspect seems particularly useful. Especially if combined with performance measurement, duration could be quite informative with regard to key aspects, such as firms’ reactiveness to changes, speed of learning, and behavioral aspects, such as persistence in fighting against emerging problems.

Finally, while interesting research opportunities could also arise from studying the remaining questions individually (Who? Where?), their stronger contribution is likely to lie in their combination, as well as in their coupling with the former “Why?” and “How?” questions. In fact, it seems plausible that the motivations and behaviors of reshoring firms could depend on firms’ and (home and host) countries’ characteristics. Thus, inclusion of these questions in the future research agenda will prove useful to providing a more compelling and exhaustive characterization and comprehension of the reshoring phenomenon.

A final remark can be made regarding research proposals involving actors in the reshoring phenomenon outside firms, namely policy makers and customers. The role of government was investigated by Bailey and De Propris (2014a, b); however, we suggest further investigation with regard to the effectiveness of specific incentives (e.g., financial aid, investments in infrastructure and/or in human capital development). Regarding customers, Grappi et al. (2015) offered interesting starting points for further investigations; among them, we suggest focusing on the impact of the “made in” effect (Bertoli and Resciniti 2012) on consumers’ choices when production is reshored.

While the present literature review is primarily academic, its content could be of interest to managers. In particular, in summarizing the outcomes of past research on the location-governance type of issue, our work informs managers of the distinct, yet intimately related, nature of these two decisions. Managers should consider that, while reshoring can happen without any changes in the governance form, in practice its feasibility and effectiveness can be seriously influenced by the decisions on governance. At the same time, by summarizing the extant knowledge on reshoring motivations we offer a meaningful list of potential drivers that managers can keep in mind, should they have to reconsider their location decision. It will then be their task to examine the relevance of the various drivers in the specific context of their own activities.

It is our belief that researching manufacturing reshoring decision is timely and relevant. There is value in studying the reshoring phenomenon per se, because the relocation decision comes after the firm has acquired some type of (direct) experience in operating abroad, and it can have several different company-wide implications. While past studies have argued that the learning derived from (international) experience would permit firms to overcome their unfamiliarity with new business environments (e.g., Camuffo et al. 2007; Johanson and Vahlne 1990) reshoring might show that this outcome is not necessarily certain. Rather, firms might not be able to overcome obstacles due to internationalization (Kinkel 2012), or they might realize that attempting to do so is not desirable, e.g., due to excessive risk (Figueira-de-Lemos et al. 2011; Gray et al. 2013) or changes in the firm’s strategic priorities (Grandinetti and Tabacco 2015).

Secondly, it is relevant to study reshoring as part of a firm’s internationalization path. Reshoring supports the viewpoint that this path does not necessarily follow a pure expansion pattern but rather a non-linear trajectory, in which steps of increased commitment can alternate with others of reduced commitment (Fratocchi et al. 2015). At the same time, specific attention should be paid to understand why manufacturing reshoring is (or is not) preferred to other alternative decisions, such as near-reshoring and further offshoring (Joubioux and Vanpoucke 2016; Murat 2013).

While we believe we have conducted a rigorous and useful piece of research, we also acknowledge that it has limitations. First—mostly due to the actual state of research on reshoring—our work is explorative and descriptive in nature, and as the literature is still developing could not be conclusive on certain issues; further research is required to enhance the characterization and comprehension of the phenomenon. A second limitation is that we decided to focus on a database that is mostly focused on academic sources. While this choice helped to access literature that is more appropriate for the rigorous characterization of reshoring we wanted to pursue, it is likely that we overlooked anecdotal evidence, managerial debates and other types of documents that could however prove to have some usefulness to such a characterization.

In conclusion, we perceive reshoring to be a critical element of the ongoing debate regarding how internationalization can be appropriately explained in the rapidly changing global environment, as well as the key capabilities that a firm must possess to succeed in this (Contractor et al. 2010; Mugurusi and de Boer 2014).

Notes

- 1.

See Sect. 2.

References

(*The article is included in the literature review)

Abassi H (2016) It is not offshoring or reshoring but right shoring that matters. J Text Apparel Technol Manag 10(2)*

Albertoni F, Elia S, Massini S, Piscitello L (2017) The reshoring of business services: reaction to failure or persistent strategy?. J World Bus, Vol. In Press, Corrected Proof

Ancarani A, Di Mauro C, Fratocchi L, Orzes G, Sartor M (2015) Prior to reshoring: a duration analysis of foreign manufacturing ventures. Int J Prod Econ 169:141–155*

Arlbjørn JS, Lüthje T (2012) Global operations and their interaction with supply chain performance. Ind Manag Data Sys 112(7):1044–1064

Arlbjørn JS, Mikkelsen OS (2014) Backshoring manufacturing: notes on an important but under-researched theme. J Purchasing Supply Manag 20(1):60–62*

Ashby A (2016) From global to local: reshoring for sustainability. Oper Manag Res 9(3):75–88*

Bailey D, De Propris L (2014a) Manufacturing reshoring and its limits: the UK automotive case. Camb J Reg Econ Soc 20(1):66–68*

Bailey D, De Propris L (2014b) Reshoring: opportunities and limits for manufacturing in the UK—the case of the auto sector. Revue d’économie industrielle 1(145):45–61*

Baldwin R, Venables AJ (2013) Spiders and snakes: offshoring and agglomeration in the global economy. J Int Econ 90(2):245–254*

Bals L, Kirchoff JF, Foerstl K (2016) Exploring the reshoring and insourcing decision making process: toward an agenda for future research. Oper Manag Res 9(3):102–116*

Beer S (1972) Brain of the firm: the managerial cybernetics of organization. Allen Lane, London, UK

Beer S (1984) The viable system model: its provenance, development, methodology and pathology. J the Oper Res Soc 35(1):7–25

Bertoli G, Resciniti R (eds) (2012) International marketing and the country of origin effect: the global impact of “Made in Italy”. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK

Bellego C (2014) Reshoring: a multifaceted decision involving much more than just labour costs. Les 4 Pages de la direction géneral de la competitivitè, de l’industrie et des services (30):1–4

Belussi F (2015) The international resilience of Italian industrial districts/clusters (ID/C) between knowledge re-shoring and manufacturing off (near)-shoring. Investigaciones Regionales—J Reg Res 32:89–113

Benito GR, Petersen B, Welch LS (2009) Towards more realistic conceptualisations of foreign operation modes. J Int Bus Stud 40(9):1455–1470

Camuffo A, Furlan A, Romano P, Vinelli A (2007) Routes towards supplier and production network internationalisation. Int J Oper Prod Manag 27(4):371–387

Canham S, Hamilton RT (2013) SME internationalisation: offshoring, “backshoring”, or staying at home in New Zealand. Strateg Outsourcing: An Int J 6(3):277–291*

Contractor FJ, Kumar V, Kundu SK, Pedersen T (2010) Reconceptualizing the firm in a world of outsourcing and offshoring: the organizational and geographical relocation of high-value company functions. J Manage Stud 47(8):1417–1433

Cowell M, Provo J (2015) Reshoring and the “manufacturing moment”. In: Bryson JR, Clark J, Vanchan V (eds) Handbook of Manufacturing Industries in the World Economy. Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd., Cheltenham, UK, pp 71–83*

De Backer K, Menon C, Desnoyers-James I, Moussiegt L (2016) Reshoring: Myth or Reality? OECD Publishing, Paris, France. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jm56frbm38s-en. Accessed 14 Mar 2016

Denning S (2013) Boeing’s offshoring woes: seven lessons every CEO must learn. Strategy Leadersh 41(3):29–35*

Denyer D, Tranfield D (2009) Producing a systematic review, In: Buchanan DA, Bryman A (eds) The Sage handbook of organizational research methods. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp 671–689

Ellram LM (2013) Offshoring, reshoring and the manufacturing location decision. J Supply Chain Manag 49(2):3–5

Ellram LM, Tate WL, Petersen KJ (2013) Offshoring and reshoring: an update on the manufacturing location decision. J Supply Chain Manag 49(2):14–22*

European Parliament Resolution (2014) Reindustrializing Europe to promote competitiveness and sustainability, Strasbourg. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+REPORT+A7-2013-0464+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN. Accessed 15 Jan 2016

Figueira-de-Lemos F, Johanson J, Vahlne J-E (2011) Risk management in the internationalization process of the firm: a note on the Uppsala model. J World Bus 46(2):143–153

Fink A (2005) Conducting research literature reviews: from the internet to paper. Sage Publications, London, UK

Foerstl K, Kirchoff JF, Bals L (2016) Reshoring and insourcing: drivers and future research directions. Int J Phys Distrib Logistics Manag 46(5):492–515*

Foster K (2016) A prediction of U.S. Knit apparel demand: making the case for reshoring manufacturing investments in new technology. J Text Apparel Technol Manag 10(2)*

Fox S (2015) Moveable factories: how to enable sustainable widespread manufacturing by local people in regions without manufacturing skills and infrastructure. Technol Soc 42(August)*

Fratocchi L, Ancarani A, Barbieri P, Di Mauro C, Nassimbeni G, Sartor M, Vignoli M, Zanoni A (2015) Manufacturing back-reshoring as a nonlinear internationalization process. In: van Tulder R, Verbeke A, Drogendijk R (eds) The future of global organizing, Progress in International Business Research (PIBR). Emerald, pp 367–405*

Fratocchi L, Ancarani A, Barbieri P, Di Mauro C, Nassimbeni G, Sartor M, Vignoli M, Zanoni A (2016) Motivations of manufacturing reshoring: an interpretative framework. Int J Phys Distrib Logistics Manag 46(2):98–127*

Fratocchi L, Di Mauro C, Barbieri P, Nassimbeni G, Zanoni A (2014a) When manufacturing moves back: concepts and questions. J Purchasing Supply Manag 20(1):54–59*

Fratocchi L, Iapadre L, Ancarani A, Di Mauro C, Zanoni A, Barbieri P (2014b) Manufacturing reshoring: threat and opportunity for East Central Europe and Baltic Countries. In: Zhuplev A (ed) Geo-regional competitiveness in Central and Eastern Europe, The Baltic Countries, and Russia, IGI Global, 83–118*

Grandinetti R, Tabacco R (2015) A return to spatial proximity: combining global suppliers with local subcontractors. Int J Globalisation Small Bus 7(2):139–161*

Grappi S, Romani S, Bagozzi RP (2015) Consumer stakeholder responses to reshoring strategies. J Acad Mark Sci 43(4):453–471*

Gray JV, Skowronski K, Esenduran G, Johnny Rungtusanatham M (2013) The reshoring phenomenon: what supply chain academics ought to know and should do. J Supply Chain Manag 49(2):27–33*

Greenwood M (2011) Which business and management journal database is best? [Online], available at: https://bizlib247.wordpress.com/2011/06/19/which-business-and-management-journal-database-is-best/. Accessed 23 Aug 2013

Guenther G (2012) Federal tax benefits for manufacturing: current law, legislative proposals, and issues for the 112th Congress

Gylling M, Heikkilä J, Jussila K, Saarinen M (2015) Making decisions on offshore outsourcing and backshoring: a case study in the bicycle industry. Int J Prod Econ 162:92–100*

Handley SM (2012) The perilous effects of capability loss on outsourcing management and performance. J Oper Manag 30(1–2):152–165

Hogg D (2011) Lean in a changed world. Manufacturing Engineering, September, pp 102–113*

Huq F, Pawar KS, Rogers H (2016) Supply chain configuration conundrum: how does the pharmaceutical industry mitigate disturbance factors? Prod Plann Control 27(14):1206–1220*

Jensen PDØ, Larsen MM, Pedersen T (2013) The organizational design of offshoring: taking stock and moving forward. J Int Manag 19(4):315–323

Johanson J, Vahlne J-E (1990) The mechanism of internationalisation. Int Mark Rev 7(4):11–23

Joubioux C, Vanpoucke E (2016) Towards right-shoring: a framework for off-and re-shoring decision making. Oper Manag Res 9(3):117–132*

Kinkel S (2012) Trends in production relocation and backshoring activities: changing patterns in the course of the global economic crisis. Int J Oper Prod Manag 32(6):696–720*

Kinkel S (2014) Future and impact of backshoring—some conclusions from 15 years of research on German practices. J Purchasing Supply Manag 20(1):63–65*

Kinkel S, Lay G, Maloca S (2007) Development, motives and employment effects of manufacturing offshoring of German SMEs. Int J Entrepreneurship Small Bus 4(3):256–276

Kinkel S, Maloca S (2009) Drivers and antecedents of manufacturing offshoring and backshoring—a German perspective. J Purchasing Supply Manag 15(3):154–165*

Lam H, Khare A (2016) Addressing Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity & Ambiguity (VUCA). In: Mack O, Khare A, Krämer A, Burgartz T (eds) Managing in a VUCA World. Springer, Switzerland, pp 141–149*

Livesey F (2012) The need for a new understanding of manufacturing and industrial policy in leading economies. Innovations: Technol Governance Globalization 7(3):193–202

Martínez-Mora C, Merino F (2014) Offshoring in the Spanish footwear industry: a return journey? J Purchasing Supply Manag 20(4):225–237*

McIvor R (2010) Global services outsourcing. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY

Mezzadri A (2014) Backshoring, local sweatshop regimes and CSR in India. Competition Change 18(4):327–344*

Moradlou H, Backhouse C (2014) Re-shoring UK manufacturing activities, supply chain management & postponement issues. Proc Inst Mech Eng, Part B: J Eng Manuf 230(9):1561–1571*

Mugurusi G, de Boer L (2013) What follows after the decision to offshore production?: a systematic review of the literature. Strateg Outsourcing: Int J 6(3):213–257

Mugurusi G, de Boer L (2014) Conceptualising the production offshoring organisation using the viable systems model (VSM). Strateg Outsourcing: Int J 7(3):275–298*

Murat A (2013) Framing the offshoring and re-shoring debate: a conceptual framework. J Glob Bus Manag 9(3):73

Razvadovskaya YV, Shevchenko IK (2015) Dynamics of metallurgic production in emerging countries. Asian Soc Sci 11(19):178–184*

Robinson PK, Hsieh L (2016) Reshoring: a strategic renewal of luxury clothing supply chains. Oper Manag Res 9(3):89–101*

Saki Z (2016) Disruptive innovation in manufacturing. An alternative for reshoring strategy. J Text Apparel Technol Manag 10(2)*

Schmeisser B (2013) A systematic review of literature on offshoring of value chain activities. J Int Manag 19(4):390–406

Selko A (2013) Is reshoring really working. Industry week, February, pp 27–29*

Seuring S, Gold S (2012) Conducting content-analysis based literature reviews in supply chain management. Supply Chain Manag: Int J 17(5):544–555

Srai JS, Ané C (2016) Institutional and strategic operations perspectives on manufacturing reshoring. Int J Prod Res 54:1–19*

Stentoft J, Mikkelsen OS, Jensen JK (2016a) Flexicurity and relocation of manufacturing. Oper Manag Res 9(3):133–144*

Stentoft J, Olhager J, Heikkilä J, Thoms L (2016b) Manufacturing backshoring: a systematic literature review. Oper Manag Res 9(3):53–61*

Tate WL (2014) Offshoring and reshoring: US insights and research challenges. J Purchasing Supply Manag 20(1):66–68*

Tate WL, Ellram LM, Schoenherr T, Petersen KJ (2014) Global competitive conditions driving the manufacturing location decision. Bus Horiz 57(3):381–390*

The White House (2012) Blueprint for an America Built to last, Washington, DC

Uluskan M, Joines JA, Godfrey AB (2016) Comprehensive insight into supplier quality and the impact of quality strategies of suppliers on outsourcing decisions. Supply Chain Manag: Int J 21(1):92–102*

Wu X, Zhang F (2014) Home or overseas? an analysis of sourcing strategies under competition. Manag Sci 60(5):1223–1240*

Zhai W (2014) Competing back for foreign direct investment. Econ Model 39:146–150*

Zhai W, Sun S, Zhang G (2016) Reshoring of American manufacturing companies from China. Oper Manag Res 9(3):62–74*

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Barbieri, P., Ciabuschi, F., Fratocchi, L., Vignoli, M. (2017). Manufacturing Reshoring Explained: An Interpretative Framework of Ten Years of Research. In: Vecchi, A. (eds) Reshoring of Manufacturing. Measuring Operations Performance. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58883-4_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58883-4_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-58882-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-58883-4

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)