Abstract

Social comparison processes may have vital consequences for perceptions of well-being among both healthy individuals as well those struggling with medical or psychological problems. According to the identification-contrast model, when individuals are confronted with a stressful event, they will try to re-establish or maintain well-being and self-esteem by identifying themselves with others doing better (upward identification) and contrast themselves with others worse-off (downward contrast). The present chapter describes both correlational and experimental research in different settings, such as education, health care, personal relationships and organizations, that shows when and how individuals rely on upward identification and downward contrasts, what consequences these comparisons have on affect, mood, well-being and self-esteem, and how these comparisons interact with contextual and individual difference variables. Finally, several practical implications of social comparison research are discussed.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

It seems quite obvious that one’s well-being is to an important extent dependent on how one evaluates one’s own situation in comparison to that of others. Theorizing and research on social comparison can be traced to some of the classic contributions to Western philosophy (Suls & Wheeler, 2000). Nevertheless, it was not until Festinger’s (1954) classic paper that the term social comparison was proposed, and a detailed theory on social comparison was outlined. While Festinger’s original theory on social comparison had a restricted focus on the comparison of abilities and opinions, over the past decades work on social comparison has undergone numerous transitions and reformulations, and has developed into a lively, varied, and complex area of research encompassing many different paradigms, approaches, and applications (e.g., Buunk & Gibbons, 2006; Suls & Wheeler, 2000). An important aspect of this development is the focus of many social comparison studies on issues directly related to well-being – the quality of life among cancer patients, marital satisfaction, and occupational burnout for example – that no researcher would have considered during the early years of the theory.

Although the focus on social comparison and well-being is relatively recent, this focus can in part be traced back to the pioneering work by Schachter (1959), who was probably the first to suggest that stress enhances the need for social comparison, owing particularly to the uncertainty inherent in many stressful situations. According to Schachter (1959), “the emotions or feelings, like the opinions and abilities, require social evaluation when the emotion producing situation is ambiguous or uninterpretable in terms of past experience” (p. 129). A series of studies in the field have indeed shown that uncertainty and negative emotions may foster social comparisons. The first of these was that by Buunk, Van Yperen, Taylor, and Collins (1991), who showed that social comparison tendencies were enhanced in individuals, particularly women, facing a combination of uncertainty and dissatisfaction in their marriages (Buunk et al., 1991, Study 1). In a quite different context – i.e., nursing – similar results were obtained. Nursing is a profession in which uncertainty is rather common (e.g., Tummers, Landeweerd, & Van Merode, 2002). Nurses may, for instance, wonder if they are too involved with patients or not involved enough; they may feel uncertain how to deal with patients’ varying problems, including appeals for help and expressions of anxiety; and they may experience uncertainties about whether they are doing things correctly. Buunk, Schaufeli, and Ybema (1994) showed that, among nurses, uncertainty and emotional exhaustion – the central component of burnout – made additive and independent contributions to the desire for social comparison.

In a similar vein, Buunk (1995) conducted a study among individuals receiving disability payments in a period when a new Disablement Insurance Act in The Netherlands was proposed that created a lot of uncertainty among aforementioned individuals. The results of this study clearly showed that uncertainty and negative emotions such as frustration were related to the desire for social comparison information, i.e., information about the feelings and opinions of other individuals receiving disability payments. Also in other contexts, an enhanced need for social comparison information has been found among individuals facing insecurity and stress. For instance, Blanchard, Blalock, DeVellis, DeVellis, and Johnson (1999) found that mothers of premature infants made more social comparisons than mothers of full-term infants, suggesting an enhanced need for information about how others in a similar situation are coping.

In the remaining part of this chapter, we describe how the nature of social comparison processes may both depend on one’s well-being and contribute to perceptions of well-being. We take the identification-contrast model developed by Buunk and Ybema (1997) as a starting point and outline the way stress may activate a coping process through which positive emotions are generated and self-esteem is restored by identifying with others better-off and by finding ways to feel that one is – at least in some ways – better-off than others. We focus on a variety of settings, including work, close relationships, serious diseases, and aging, and pay attention to depression. First, we describe the model in general. Second, we present correlational studies on how the perceived positive and negative emotions evoked by social comparison are related to indices of well-being – or lack thereof – including burnout, positive emotions, and perceived quality of life. Third, we describe a series of experimental studies on the effects of exposure to social comparison targets on affect and well-being. Fourth, we discuss how individuals may construct an image of themselves and their close others that enhances their well-being. Finally, some practical implications of social comparison research are discussed.

The Identification-Contrast Model

Social comparisons may be related to well-being in very different ways, depending on, first, the direction in which individuals compare themselves with others. Individuals may compare themselves with others who are better-off (so-called upward comparisons), or with others who are worse-off (so-called downward comparisons). Second, the interpretation of social comparison is relevant when considering its relation with well-being. According to the identification-contrast model proposed by Buunk and Ybema (1997), individuals may contrast themselves with a comparison target (i.e., evaluate themselves by focusing on the differences between themselves and the target), or they may identify themselves with a comparison target (i.e., recognize features of themselves in the other, and regard the other’s position as similar to their own position or as attainable for themselves). As a consequence, individuals may follow – not necessarily exclusively – four strategies: upward identification, upward contrast, downward contrast, and downward identification (Van der Zee, Bakker, & Buunk, 2001). In general, when individuals identify themselves with a comparison target, their self-image and affect are enhanced by upward comparisons and lowered by downward comparisons. Conversely, when individuals contrast themselves with a comparison target, their self-image and affect are enhanced by downward comparisons and lowered by upward comparisons. The identification-contrast model holds that people are in general motivated to identify themselves with others doing better and to contrast themselves with others doing worse. Contrast with better-off others may evoke negative feelings such as envy. For instance, among patients with a spinal cord injury, Buunk, Zurriaga, and Gonzalez (2006) found that upward contrast was quite strongly related to negative emotions. Similar findings were obtained among 444 community-dwelling elderly for whom this type of social comparison was accompanied by lower life satisfaction (Frieswijk, Buunk, Steverink, & Slaets, 2004) and among 588 teachers for whom this type of social comparison was related to more burnout (Carmona, Buunk, Peiro, Rodriguez, & Bravo, 2006).

The identification-contrast model links such findings to evolutionary psychology and assumes that human beings compete with each other for status and prestige in groups. Individuals have a deeply rooted tendency to try to reach a state in which they feel that they are in some respects more attractive and talented or otherwise better-off than other group members. From an evolutionary perspective, this search for symbolic dominance over others is the translation of the physical struggle among primates for social dominance in a group. As noted by Barkow (1989), such a group need not actually exist and may be cognitively constructed: “With human self-esteem others not only need not be physically present, they need not have physical existence” (p. 191). When individuals are confronted with a stressful event, their sense of relative superiority is violated, and they have a need to re-establish such a self-perception. They will try to identify themselves with others doing better and see these others as similar to themselves, and regard the lot of the others as their own future. On the other hand, they will try to contrast themselves with others worse-off, regarding the other’s position as a standard for themselves that may make them look better. By identifying with others doing better, individuals attain a number of things, for example the feeling of belonging to the best in their reference group, the vicarious or actual attention that is bestowed upon the high status others, the alliance of such others, and the potential of self-improvement by learning from others who are doing better (cf. Gilbert, Price, & Allan, 1995).

Social Comparisons and Well-Being: Correlational Evidence

According to the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions (Fredrickson, 2006), positive emotions may momentarily broaden people’s attention and thinking, enabling them to draw flexibly on higher level connections and wider-than-usual ranges of percepts and ideas. In turn, these broadened and flexible outlooks help people to discover and build survival-promoting personal resources, such as self-esteem and improved relations with others, that may be especially relevant for well-being. Especially upward identification as opposed to downward identification may help in evoking positive emotions. For example, a study among nurses showed that nurses who responded with more positive affect to upward comparisons, and with less negative affect to downward comparisons, showed a decrease in burnout one year later (Buunk, Zurriaga, & Peiro, 2010). In a related vein, a study by Buunk, Kuyper, and Van der Zee (2005) among 609 secondary school students showed that the most frequent type of comparison was upward identification, leading to feelings of hope that in the future one may receive a good grade similar to that of the target one was identifying oneself with. Although upward identification tends to be more common than downward contrast (e.g., Buunk, Ybema, Van der Zee, Schaufeli, & Gibbons, 2001), downward contrast and upward identification may jointly induce positive effects on well-being. For example, in a classroom study with fourth and fifth graders, Boissicat, Pansu, Bouffard, and Cottin (2012) found that the more pupils reported using upward identification and downward contrast, the higher their perceived scholastic competence was, whereas the use of downward identification and upward contrast was associated with lower perceived scholastic competence. Indeed, especially in school and classroom settings, the combination of downward contrast and upward identification seems adaptive. Downward contrasts may help students maintain high self-esteem while upward identification may help them improve themselves in terms of academic achievements (Dijkstra et al., 2008).

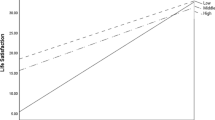

The important role of downward contrast in educational settings is corroborated by research on the big-fish–little-pond effect – the phenomenon that equally able students have lower academic self-esteem in schools or classes where the average achievement level is higher than in schools or classes where the average achievement level is low (BFLPE; see Marsh et al., 2008, for a review). Thus, in line with the identification-contrast model, academic self-esteem is improved in classes or schools that provide students with ample opportunities for downward contrast, whereas it is lowered in classes or schools that hold little opportunities for such contrast. This may shed a new light on special education classes, for instance, for the gifted or students with learning disorders. Although intellectually gifted students may benefit from special classes, their self-esteem may suffer because of the reduced opportunities that these special classes offer in terms of downward contrast. Also, those with learning problems may benefit from special classes since these classes enable them to make more downward contrasts while minimizing upward contrasts. In a quite different context, a similar effect of downward contrasts was found by Boyce, Brown, and Moore (2010), who showed that life satisfaction is related not to absolute income or the position of one’s income relative to some wage standard, but to the ranked position of one’s income within one’s own comparison group in terms of, among other things, age and educational level. As individuals perceive that they have a higher income than others in their reference group – implying downward contrast – they are more satisfied with their lives.

Especially for individuals whose well-being is under threat, upward identification may not always be possible, and downward contrast may be a more adaptive strategy to experience positive affect that may help these people build the resources they need to cope with stressful circumstances. For instance, Buunk et al. (2001) showed that while nurses high in burnout reported higher levels of negative affect from upward comparisons, they also reported higher levels of positive affect from downward comparisons than nurses low in burnout. Especially in times of economic downturn, downward contrast may become important to remain satisfied about one’s income. As a consequence, as individuals make more downward comparisons with workers in lower social groups who earn less, they may feel their earnings are fairer. In contrast, an unfair feeling, i.e. that of relative deprivation, is evoked when workers make upward comparisons, especially in times of economic downturn. Furthermore, for workers at the lowest pay levels, it may be hard to engage in downward contrast, since these individuals are already at the bottom of the pay scale. This may evoke feelings of relative deprivation and envy among such workers (Tao, 2015).

The relevance of downward contrast for individuals under stress is well illustrated by studies among individuals suffering from chronic diseases. For instance, Van der Zee et al. (1996) showed that, compared to healthy individuals, cancer patients made more frequent downward comparisons, a strategy that, according to the authors, helped cancer patients through contrasting themselves with others worse-off to maintain a similar level of subjective well-being as their healthy counterparts. Blanchard, Blalock, DeVellis, DeVellis, and Johnson (1999) showed that, compared to mothers of full-term infants, mothers of premature infants made more downward social comparisons, and made, as a consequence, more favorable evaluations of their infants relative to the typical premature baby. Indeed, in a review of 23 studies, Tennen et al. (2000) concluded that downward social comparisons are prominent in populations with serious medical problems, such as those with rheumatoid arthritis, cancer and chronic pain, and that these comparisons are generally associated with positive adjustment – assumedly due to the contrast these downward comparisons entail. Based on their finding that breast cancer patients reported a preponderance of spontaneous downward comparisons, Wood, Taylor, and Lichtman (1985) argued that regaining self-esteem is a major motive for contrasting oneself downward under stress.

While especially in the early stages of severe medical illnesses, such as cancer, patients may feel a need for social comparisons with fellow patients, in advanced stages of a potentially incurable disease, when chances of recovery are limited, patients may feel a decreased need for social comparisons with fellow patients, as these may, in many cases, be upward and contrasting in nature, primarily generating negative affect. Such effects were illustrated in a study by Morrell et al. (2012), who found that ovarian cancer patients in an advanced stage of the disease (stage III and IV) preferred to avoid contact with other ovarian cancer patients and preferred to seek the company of ‘normal’ others, for normalizing information and information that facilitated upward identification. In order to still experience some positive affect, such patients may prefer to ignore social comparison information that emphasizes the severity of their disease relative to other patients. Something similar may apply to individuals with chronic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Blalock, Afifi, DeVellis, Holt, and DeVellis (1990), for instance, showed that nearly 50% of unprompted social comparisons involved others not affected by RA. After controlling for differences in physical health status, patients who emphasized their similarity to, rather than their differences from, individuals not affected by RA exhibited better psychological adjustment. In line with the identification-contrast model, especially in downward comparison, feelings of negative affect were mediated by identification with downward comparison others (also see DeVellis et al., 1990, who found a preponderance of downward comparisons associated with negative affect among patients suffering from RA).

Individual Differences

Not everyone seems equally able to use upward identification and downward contrast in order to enhance their well-being. Several studies show that individuals high in neuroticism tend to identify themselves with others who are worse-off (e.g., Buunk, Van der Zee, & Van Yperen, 2001; Van Oudenhoven-Van der Zee, Buunk, Sanderman, Botke, & Van den Bergh, 1999). Other studies show that neurotic individuals more frequently make both upward and downward comparisons, with both types of comparison generating relatively high levels of negative affect; in other words, highly neurotic people engage in upward contrast and downward identification (Van der Zee, Buunk, & Sanderman, 1996; Van der Zee, Oldersma, Buunk, & Bos, 1998). Similar findings have been reported for self-esteem, one of the components of neuroticism (e.g., Buunk, Collins, Taylor, Van Yperen, & Dakoff, 1990). These findings are in line with the general literature on neuroticism, self-esteem, and coping (e.g. Mohiyeddini, Bauer, & Semple, 2015), which shows that neurotic and low self-esteem individuals show relatively inadequate coping strategies in response to stress. It seems that, in general, neurotic and low self-esteem individuals find it relatively difficult to generate the positive emotions needed to build survival-promoting personal resources in times of stress.

Another individual difference variable that affects the relationship between well-being and social comparisons is social comparison orientation (SCO). Gibbons and Buunk (1999) introduced this concept to refer to the personality disposition of individuals who are strongly focused on social comparison. Such individuals may compare themselves more frequently with others, particularly those in similar situations, and they should be more sensitive to social comparison information (see also Buunk & Gibbons, 2006). To measure SCO, Gibbons and Buunk constructed a scale with 11 items that are presented in Table 17.1.

In a representative sample of Dutch citizens of all age groups, the scale had a normal distribution with a skewness of −.18. The mean (M = 32.7) as well as the median (Md = 33) were both virtually identical to the scale midpoint (33), which suggests that there are as many high comparers as there are low comparers. Individuals high in SCO seem to have a high chronic activation of the self as SCO is quite strongly related to public and private self-consciousness (Gibbons & Buunk, 1999); in fact, these are among the strongest correlates of SCO, varying from r = .38 to .49. Thus, those high in SCO tend to be particularly aware of themselves in the presence of others and tend to engage in reflection upon their own thoughts and feelings. In addition, individuals high in SCO are characterized by a strong interest in what others feel, a strong empathy for others, and a general sensitivity to the needs of others. Indeed, in addition to self-consciousness, one of the strongest correlates of SCO is interpersonal orientation (r = .45, p < .001), a construct that includes an interest in what makes people tick, as well as a tendency to be influenced by the moods and criticism of others, and an interest in mutual self-disclosure – all aspects that are characteristic of individuals with a high interdependent self (Swap & Rubin, 1983). As might be expected, there is also a negative correlation (r = −.35, p < .001) between SCO and the Big Five trait intellectual autonomy (or openness to experience as it is sometimes called; Gibbons & Buunk, 1999). This means that those high in SCO are generally somewhat lower in independent and creative thinking, or, put differently, higher in conformity. Finally, SCO has generally low correlations with depression, anxiety, neuroticism, and low self-esteem (Gibbons & Buunk, 1999).

The associations involving SCO are, however, more complex than initially thought. For example, Buunk, Zurriaga, Peíró, Nauta, and Gosalvez (2005) showed that employees high in SCO reported more contrast in their social comparisons, i.e., they reported more positive affect after downward comparisons, and more negative affect after upward comparisons. Along similar lines, a number of studies suggest that SCO may moderate associations between engaging in social comparison and well-being. In a study among nurses, Buunk, Zurriaga, and Peiro (2010) found that especially among individuals with a high SCO score, the frequency of comparisons was a predictor of feelings of burnout 9–10 months later. In a study among cancer patients, Van der Zee, Oldersma, Buunk, and Bos (1998) found that patients high in SCO responded with more negative reactions (such as identification) to downward comparisons. In addition, individuals high in SCO are sensitive to the experience of relative deprivation – that is, resentment originating from the belief that one is deprived of desired and deserved outcomes compared to others (also see Callan, Kim, & Matthews, 2015). In a longitudinal study among nurses, Buunk, Zurriaga, Gonzalez-Roma, and Subirats (2003) found that relative deprivation had increased particularly among nurses high in social comparison orientation who, 10 months earlier, had engaged more often in downward and upward comparisons and had derived more feelings from these comparisons. This heightened sense of relative deprivation may lead to higher levels of psychological distress and burnout symptoms, undermining individuals’ well-being and the ability to cope with stress (e.g., De la Sablonniere, Tougas, De la Sablonierre, & Debrosse, 2012).

Situational Factors

In addition to individual differences, the situations individuals find themselves in may affect the association between social comparisons and well-being. For instance, Buunk et al. (2005) found that employees who perceived the social climate at work as cooperative reported more identification with their co-workers – i.e., more negative affect from downward comparisons and more positive affect from upward comparisons. Circumstances may force individuals to make social comparisons they otherwise would not make, some of which are not conducive to affect or well-being. Another important situational factor is the incentive structure at work or in the classroom (Garcia, Tor, & Schiff, 2013). A common example that emerges in the classroom is whether the course is graded on a curve or absolute scale, with the former evoking much more social comparison and producing more competitiveness than the latter. Especially competitive settings tend to evoke social comparisons characterized by contrast, a type of comparison that may, in theory, both generate positive affect (in the case of downward contrast) as well as negative affect (in the case of upward contrast). However, in competitive settings, even the positive affect evoked by downward contrast and outperforming others may be limited. The competitive success may clash with the goal of maintaining satisfying relations with others, leading outperformers to experience discomfort when they believe that their superior status poses a threat to outperformed others. Thus, although outperformance may be privately satisfying, it may cause negative affect when individuals perceive a clash with their need for interpersonal closeness (Exline & Lobel, 2001).

Social Comparison and Well-Being: Experimental Evidence

In contrast to correlational studies, experimental studies have found more direct evidence for the effects of social comparison on well-being, though these effects are not always similar to what correlational studies would suggest. In these experimental studies, respondents are presented with a vivid description of a comparison target that is depicted as either being better-off on a particular dimension (upward comparison) or worse-off (downward comparison). It is sometimes argued that this type of manipulation is somewhat artificial since in real life individuals may not chose to compare themselves with the target they are presented with, because, for instance, they usually avoid upward comparisons or hardly make social comparisons at all. Nonetheless, these studies are important sources of knowledge, since often social comparisons are not just a matter of choice. In many settings, such as offices, classrooms and hospitals, it is almost impossible not to compare oneself with others (e.g., Dijkstra, Kuyper, Van der Werf, Buunk, & Van der Zee, 2008). In addition, experimental studies may help clarify how interventions that aim to increase well-being may use social comparison information to reach this aim.

In general, experimental studies suggest that, in line with the identification-contrast model, individuals tend to identify themselves with upward targets, but that a high degree of stress may hinder such identification. For instance, among socio-therapists, Buunk, Ybema, Gibbons, and Ipenburg (2001) found that an upward comparison target generated more positive and less negative affect than a downward comparison target. However, as in the correlational study among nurses by Buunk et al. (2001), those high in burnout reported lower levels of positive affect from upward comparisons. In fact, as suggested by correlational studies, those experiencing stress may benefit more from downward contrast. For example, in a study among disabled individuals, Buunk and Ybema (1995) found that, especially among those who experienced high degrees of stress, exposure to downward comparisons contributed positively to the evaluation of one’s situation.

Nevertheless, overall, and not only among those under stress, exposure to downward comparison targets may contribute to well-being, assumedly because it induces downward contrast. For example, Vogel, Rose, Roberts, and Eckles (2014) showed that exposure to downward comparison targets on social media (e.g., a low activity social network, unhealthy habits) resulted in higher self-esteem than exposure to upward comparison targets (e.g., a high activity social network, healthy habits). In a similar vein, Reis, Gerrard, and Gibbons (1993) found that women who compared themselves with a woman who used contraceptives ineffectively demonstrated more self-esteem improvement than women who compared themselves with a female who used contraceptives effectively.

Not only the direction, but also the content of the social comparison information may be important. For instance, Bennenbroek et al. (2003) presented cancer patients with audiotapes of fellow cancer patients talking about different elements of their treatment and disease: either the procedure of the treatment (1), their emotions about the disease and the treatment (2), or the way they coped with their disease (3). This study showed that mood was elevated and self-efficacy increased when patients listened to fellow patients talking about the procedure or coping (but not about their emotions), suggesting that social comparison about procedure and coping may be useful supplements for patient educational material (however, see a study by Brakel, Dijkstra, Buunk, & Siero, 2012, according to which the content of the tape may be less important).

Individual Differences

Several studies suggest that individual differences may moderate the positive effects of downward comparisons. For instance, Aspinwall and Taylor (1993) showed that downward comparison information, compared to no comparison information, caused low-self-esteem students to report more favorable self-evaluations and greater expectations of future success in college (also see Tesser, 2000). Both Gibbons and McCoy (1991) and Gibbons and Gerrard (1989) found that low but not high self-esteem people showed mood improvement after downward comparisons. In a similar vein, Gibbons (1986) showed that downward comparison information – reading about a person who was currently experiencing highly negative affect – improved the mood states of depressed individuals, but not of non-depressed individuals, suggesting that realizing that others are doing worse may help depressed people feel somewhat better.

As we suggested above, there is also evidence that SCO may moderate the effects of exposure to social comparisons. For instance, a study that was done as a follow up to the earlier mentioned study by Bennenbroek et al. (2003) showed that with increasing SCO, 2 weeks and 3 months later, a lower quality of life was reported when, prior to radiation therapy, patients had listened to the emotion tape, while a higher quality of life was reported when patients had listened to the coping tape (Buunk et al., 2012). The important role of SCO in moderating the effects on well-being of exposure to social comparison targets was also highlighted in a study by Buunk and Brenninkmeyer (2001) among depressed and non-depressed individuals. This study showed that, among the non-depressed, with increasing levels of SCO, a comparison target who overcame his or her depression through active coping (high effort) evoked a relatively positive mood whereas a comparison target who overcame his or her depression seemingly by itself (low effort) evoked a relatively negative mood. In contrast, among the depressed, with increasing levels of SCO, the low-effort target evoked a relatively positive mood change, and the high-effort target a relatively more negative one. Well-intended educational material that aims to inspire depressed patients by presenting a former depressed patient who overcame his depression by active coping may therefore have adverse effects for at least some patients. Indeed, for depressed patients, active coping may seem unattainable, since an important symptom of depression is passivity and a lack of energy. Because of their heightened reactivity to social comparison information, this may have a negative effect on mood, especially among those high in SCO.

Nevertheless, in line with the correlational studies mentioned earlier, SCO may also under certain conditions enhance contrast effects on well-being. For example, Buunk, Groothof, and Siero (2007) found that individuals who were exposed to a comparison target with a very dissatisfying social life evaluated their own social life as better than participants who were exposed to a comparison target with a very satisfying social life, but only among individuals high in SCO, suggesting that individuals high in SCO tend contrast themselves more with others. A possible explanation for the diverse effects of SCO is that SCO interacts with other situational and individual differences variables, such as the dimension under comparison, in determining identification or contrast with a comparison target.

Comparison Target

Not only individual differences, but also features of the upward and downward comparison targets may moderate the effects of social comparison. For instance, experimental studies in the domain of personal relationships have shown that the extent to which a comparison target puts in effort plays a role in the degree to which social comparisons with regard to one’s marriage may affect mood. More specifically, Buunk and Ybema (2003) examined the effects of social comparison with the marriage of another woman upon women’s mood by presenting participants with a story of either a (1) happily married woman who put a lot of effort into her marriage, (2) a happily married woman who did not put effort into her marriage, (3) an unhappily married woman who put a lot of effort into her marriage, or (4) an unhappily married woman who did not put effort into her marriage. Results showed that upward targets evoked more positive mood than downward targets, and that women tended to identify themselves particularly with the upward high effort target. However, downward comparisons, although negatively affecting mood, resulted in a more positive evaluation of one’s own relationship than upward comparisons, suggesting an effect of identification on mood, and an effect of contrast on self-evaluation. In a follow-up study, Buunk (2006) also examined the role of SCO, finding that, as individuals were higher in SCO, the high-effort couple evoked more positive affect and more identification whereas the low-effort couple evoked more negative affect and less identification. Additional evidence for a higher tendency to identify oneself with better-off others among those high in SCO comes from a study by Bosch, Buunk, Siero, and Park (2010) who found that, as women were higher in SCO, exposure to an attractive target (upward comparison) was positively related to self-evaluations of attractiveness, whereas exposure to a less attractive target (downward comparison) was related negatively to self-evaluations of attractiveness.

Construing Oneself as Better-Off Than Others

While the studies described above involve self-reported or actual exposure to social comparison targets, individuals may also cognitively construct such targets. An important implication of the identification-contrast model is that, in line with what evolutionary psychology would predict, individuals have a “wired in” tendency to develop a positive self-concept – or high self-esteem – by attaining a subjective feeling of doing better than others on relevant dimensions. Therefore, individuals who are able to actively attain and maintain this feeling by cognitively constructing themselves as better-off than others will exhibit higher levels of adjustment and mental health (e.g., Taylor & Brown, 1988). A positive self-concept or high self-esteem based on such cognitive constructions may generate the positive affect that helps build the resources individuals need to cope with stress and may help individuals conquer obstacles and take on life’s challenges, facilitating adaptive coping with stressors (e.g., Fickova & Korcova, 2000; Tomaka, Morales-Monks, & Shamaley, 2013) and fostering perseverance and performance (e.g., Sommer & Baumeister, 2002).

The tendency to rate oneself as being higher on positive attributes and lower on negative attributes than most other people has been referred to as the better-than-average (BTA) effect (e.g. Kuyper et al., 2011; also called illusory superiority: Hoorens, 1995). In studies assessing the BTA effect, individuals usually compare themselves with a relatively ambiguous group of others (‘most other people’) or an ambiguous comparison target (the ‘average’ or ‘typical’ person) that provides plenty of opportunities for self-enhancement. The BTA effect has been observed in a variety of settings. For example, in work settings, Meyer (1980) found that most people felt they performed better than about 75% of others with the same job. Only very few people considered themselves below average. No less than 80% of higher professionals and managers typically feel that they are among the top 10% at their jobs. Likewise, among more than 15,000 secondary school students in The Netherlands, Kuyper et al. (2011) found that most children thought they were more athletic, more likeable, more attractive and more capable of getting high grades than most of their classmates. In a similar vein, undergraduate students believe that they are more likely than their peers to use condoms when having sex with someone for the first time (Ross & Bowen, 2010). It must be noted that, from the individual’s point of view, the perception of being better than others may be completely correct, for instance because one is indeed a better manager than other managers. However, for attributes for which the distribution in the population is about normal, it is not possible for the majority of people to be above average. Therefore, the belief of most people that they are better than average is biased and inaccurate (Kuyper et al., 2011).

Because particularly close others are often perceived as part of the self, individuals may also tend to positively bias the image they have of their close relationships (e.g. Fowers, Veingrad, & Dominics, 2002), resulting in an ‘extended’ BTA effect. For instance, Buunk (2001) as well as Rusbult, Van Lange, Wildschut, Yovetich, and Verette (2000) found that most individuals tended to view their own relationship as better than the relationships of most others (also see Buunk & Van Yperen, 1991). In a similar vein, Suls, Lemos, and Stewart (2002) found that, although undergraduates attributed more positive traits to themselves relative to the ‘average’ undergraduate, they also rated their friends as superior on these traits than the ‘average’ undergraduate.

In general, a feeling of being better-off than others is associated with high well-being, and a feeling of being worse-off is associated with low well-being. This is quite obvious in work settings. Brenninkmeyer, Van Yperen, and Buunk (2001) found that, while compared to teachers low in burnout, teachers high in burnout could generate negative behaviors they showed less often than other teachers, they were no longer able to mention positive behaviors that they showed more often than other teachers. In a number of studies, particularly among blue-collar workers, the feeling of being worse-off than other workers was found to be accompanied by occupational stress (McKenna, 1987), and increased absenteeism (e.g., Hendrix & Spencer, 1989). Problems with well-being due to the perception of being worse-off than others may become especially salient among career oriented professionals around the age of 40, when they become concerned about the likelihood of attaining their career goals in the future, and may feel that similar others have accomplished more, which induces feelings of relative deprivation. This will be magnified by a feeling of entitlement that has been built up as a consequence of high investments during the preceding career. Due to the BTA effect, professionals around the age of 40 may think they get less than they deserve and may, for instance, feel aggrieved when others are promoted and they are not. In a study among a representative sample of professional men, Buunk and Janssen (1992) found that the highest levels of relative deprivation occurred in professionals between 35 and 45 years of age, and that only in this age group did relative deprivation correlate significantly with health complaints. Presumably, younger people still feel they have a chance to attain what they want, whereas older people may have accepted their situation. This study illustrates that, although in the short run, the BTA effect may cause people to feel good about themselves, in the long run it may lead to negative emotions, such as envy and feelings of injustice.

Also in intimate relationships, the BTA effect is very relevant to well-being. For instance, Buunk (2001) showed that the extent to which individuals viewed their relationship as superior to those of others (i.e., perceived superiority) was associated with relationship satisfaction, while Rusbult et al. (2000) found perceived superiority assessed 20 months earlier predicted relationship status (persisted vs. ended) and increases in dyadic adjustment. In addition, Buunk and Van Yperen (1991) found that the extent to which individuals perceived the input-outcome ratio of their own marriage as being better compared to similar others significantly predicted relationship satisfaction. There is also evidence that the perception of having a better relationship than most others affects well-being somewhat directly. In two studies, Buunk (1998) tested the hypothesis that when individuals first answered a question about comparative evaluation (i.e., the degree in which they felt they had a better or worse chance of having a happy intimate relationship in the future than most others) and next a question about general evaluation (i.e., the chance of having a happy intimate relationship), the correlation between both variables was much higher than when the order of the questions was reversed, assumedly because the BTA effect influenced evaluations of one’s current relationship. Even more direct, experimental evidence for effects of this type comes from a study by Buunk, Oldersma, and De Dreu (2001), who asked individuals dissatisfied with their relationship to generate aspects in which they were better-off than other couples, which resulted in enhanced relationship satisfaction, but only for those high in SCO. A similar effect was not found when individuals were simply asked to generate aspects of their relationship that were good. It seems that, like in the earlier mentioned study by Buunk et al. (2007), only individuals high in SCO are sensitive to downward contrasts and may profit from their beneficial effects.

Practical Implications

Research on social comparison reveals many different avenues for interventions that may increase well-being, self-esteem, and positive affect. First, downward contrasts may help students maintain high self-esteem while upward identification may help them improve themselves in terms of academic performance (Dijkstra et al., 2008). This is important knowledge for teachers and parents, for example, when considering special classes for a child. More specifically, an intellectually gifted pupil may benefit from a special class in terms of achievements because, compared to a mainstream class, special classes for gifted pupils increase the possibilities for upward identification. However, special classes may also reduce opportunities for downward contrast, and as a consequence, lower gifted pupils’ self-esteem. Special classes for gifted pupils may therefore be only or especially beneficial to those pupils whose self-esteem is adequate, making a child’s self-esteem, for both teachers and parents, an important factor when deciding about special classes for a gifted child. In contrast, for children whose achievements in mainstream classes are lower, for example because of a learning disability, the reverse seems true. Although in this case special classes may enhance the self-esteem of low-performing pupils, they provide little opportunity for upward identification and, as a consequence, little opportunity to improve one’s performances. Special classes for low-performing pupils may therefore be only or especially beneficial to those pupils whose self-esteem is low and whose academic achievements suffer from this low self-esteem. In such cases, special classes could constitute a form a temporary intervention that helps low-performing pupils develop a more robust and positive self-image, after which they may again participate in mainstream classes where their academic achievements may profit from upward identifications.

Second, our review shows that upward contrasts may lead to envy and feelings of injustice that may undermine relationships and, in organizations, reduce performance. In organizations, these upward contrasting social comparisons may be reduced by stimulating workers to perceive themselves and their work as unique. The manager may, for instance, provide personal feedback to workers, in which he or she underlines what is special about each worker and in what exclusive way the worker contributes to the goals of the organization. A sense of uniqueness may diminish the need for social comparison: because workers perceive themselves as ‘different’ from co-workers, there seems little sense in making such comparisons. Such an intervention, however, may also reduce the positive effects that social comparisons have at work, such as the inspiration that may come along with upward identification. Rather than aiming to reduce social comparisons in general, organizations may therefore try to influence and change potentially destructive social comparison tendencies, for example by providing information that causes upward contrasts to be replaced by upward identifications. This may be done by using and communicating objective and clear criteria for rewards, such as promotions, while also being clear about why non-promotions are occurring. This information may strengthen feelings of procedural and distributional justice by helping workers realize that the rewarded co-worker has indeed deserved his or her reward and that decisions concerning the allocation of rewards are made in a fair way (e.g., Garcia-Izquierdo, Moscoso, & Ramos-Villagrasa, 2012).

Third, findings from social comparison research among patients suffering from a medical disease may provide insight in the best way to develop patient educational material. Bennenbroek et al. (2003) found that information from fellow patients about treatment procedures and effective ways of coping enhanced mood and self-efficacy, in contrast to information about fellow patient emotions, which decreased well-being. Patient educational material should therefore focus especially on fellow patients’ perceptions of procedure, treatment and coping while avoiding narratives of distress. In addition, to prevent ‘emotional contagion’ of negative emotions among patients, fellow patient groups may be best led by professional caretakers, who can help the group focus on information directly relevant to what one can expect in treatment.

Fourth, relationship counselling for distressed couples may use interventions based on social comparison research to help couples regain or strengthen a positive sense of their relationship (Buunk et al., 2001). A counsellor, for instance, may ask partners to each make a list of characteristics according to which their relationship is better than those of others and discuss the lists with the couple. This intervention may help couples shift the focus from what is negative about their relationship to more positive aspects, which will help them see why their relationship is still worth fighting for.

Conclusions

In line with humans’ social nature, both correlational and experimental studies convincingly show that social comparisons – both spontaneous and forced – may strongly affect people’s mood states, perceptions of well-being, and perceptions of self and close others. The studies reviewed in this chapter largely show evidence for the identification-contrast model. That is, to experience positive affect and enhanced well-being, and to view the self and one’s close relations as superior, individuals prefer to identify with similar others doing better or, if this possibility is limited, contrast with similar others doing worse. The identification-contrast model is highly compatible with the evolutionary psychological assumption that social cognition is shaped by humans’ striving for survival and reproduction (e.g., Seyfarth & Cheney, 2015), and that individuals may use social comparisons to facilitate this striving. More specifically, by selectively comparing the self with others, humans may maintain or generate positive affect, perceptions of increased well-being, self-esteem and improved relationships with others that may promote survival and reproduction, especially under conditions of stress, when survival and reproduction are challenged.

Although the identification-contrast model describes how individuals tend to compare themselves in general, in line with evolutionary psychological assumptions, humans also show high flexibility when it comes to the use of social comparisons. That is, exactly how individuals compare themselves with similar others and what the effects of these comparisons are depends on individual difference variables, such as SCO, self-esteem and one’s level of well-being, as well as the situation individuals find themselves in. The findings on social comparison are not only theoretically relevant, but may have important practical implications for interventions in health and educational settings, organizations, and close relationships, underlining the importance of social comparisons as determinants and change avenues for well-being.

References

Aspinwall, L. G., & Taylor, S. E. (1993). Effects of social comparison direction, threat, and self-esteem on affect, self evaluation, and expected success. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 708–722.

Barkow, J. H. (1989). Darwin, sex, and status: Biological approaches to mind and culture. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Bennenbroek, F. T. C., Buunk, A. P., Stiegelis, H. E., Hagedoorn, M., Sanderman, R., Van den Bergh, A. C. M., et al. (2003). Audiotaped social comparison information for cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy: Differential effects of procedural, emotional and coping information. Psycho-Oncology, 12, 567–579.

Blalock, S. J., Afifi, R. A., DeVellis, B. M., Holt, K., & DeVellis, R. F. (1990). Adjustment to rheumatoid arthritis: The role of social comparison processes. Health Education Research, 5, 361–370.

Blanchard, L. W., Blalock, S. J., DeVellis, B. M., DeVellis, R. F., & Johnson, M. R. (1999). Social comparisons among mothers of premature and full-term infants. Children’s Health Care, 28, 329–348.

Boissicat, N., Pansu, P., Bouffard, T., & Cottin, F. (2012). Relation between perceived scholastic competence and social comparison mechanisms among elementary school children. Social Psychology of Education, 15, 603–614.

Bosch, A. Z., Buunk, A. P., Siero, F. W., & Park, J. H. (2010). Why some women can feel more, and others less, attractive after exposure to attractive targets: The role of social comparison orientation. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 847–855.

Boyce, C. J., Brown, G. D. A., & Moore, S. C. (2010). Money and happiness: Rank of income, not income, affects life satisfaction. Psychological Science, 21, 471–475.

Brakel, T. M., Dijkstra, A., Buunk, A. P., & Siero, F. W. (2012). Impact of social comparison on cancer survivors’ quality of life: An experimental field study. Health Psychology, 31, 660–670.

Brenninkmeijer, V., Van Yperen, N. W., & Buunk, A. P. (2001). I am not a better teacher, but others are doing worse: Burnout and perceptions of superiority among teachers. Social Psychology of Education, 4, 259–274.

Buunk, A. P. (1995). Comparison direction and comparison dimension among disabled individuals: Toward a refined conceptualization of social comparison under stress. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 316–330.

Buunk, A. P. (1998). Social comparison and optimism about one’s relational future: Order effects in social judgment. European Journal of Social Psychology, 28, 777–786.

Buunk, A. P. (2001). Perceived superiority of one’s own relationship and perceived prevalence of happy and unhappy relationships. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 565–574.

Buunk, A. P. (2006). Responses to a happily married other: The role of relationship satisfaction and social comparison orientation. Personal Relationships, 13, 397–409.

Buunk, A. P., Bennenbroek, F. T., Stiegelis, H. E., Van den Bergh, A. C., Sanderman, R., & Hagedoorn, M. (2012). Follow-up effects of social comparison information on the quality of life of cancer patients: The moderating role of social comparison orientation. Psychology and Health, 27, 641–654.

Buunk, A. P., & Brenninkmeijer, V. (2001). When individuals dislike exposure to an actively coping role model: Mood change as related to depression and social comparison orientation. European Journal of Social Psychology, 31, 537–548.

Buunk, A. P., Collins, R. L., Taylor, S. E., Van Yperen, N. W., & Dakoff, G. A. (1990). The affective consequences of social comparison: Either direction has its ups and downs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1238–1249.

Buunk, A. P., & Gibbons, F. X. (2006). Social comparison orientation: A new perspective on those who do and those who don’t compare with others. In S. Guimond (Ed.), Social comparison and social psychology: Understanding cognition, intergroup relations and culture (pp. 15–33). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Buunk, A. P., Groothof, H. A. K., & Siero, F. W. (2007). Social comparison and satisfaction with one’s life. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 24, 197–206.

Buunk, A. P., & Janssen, P. P. (1992). Relative deprivation, career issues, and mental health among men in midlife. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 40, 338–350.

Buunk, A. P., Kuyper, H., & Van Der Zee, Y. G. (2005). Affective response to social comparison in the classroom. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 27, 229–237.

Buunk, A. P., Oldersma, F. L., & De Dreu, K. W. (2001). Enhancing satisfaction through downward comparison: The role of relational discontent and individual differences in social comparison orientation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 37, 452–467.

Buunk, A. P., Schaufeli, W. B., & Ybema, J. F. (1994). Burnout, uncertainty, and the desire for social comparison among nurses. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 24, 1701–1718.

Buunk, A. P., Van Yperen, N. W., Taylor, S. A., & Collins, R. L. (1991). Social comparison and the drive upward revisited: Affiliation as a response to marital stress. European Journal of Social Psychology, 21, 529–546.

Buunk, A. P., & Ybema, J. F. (1995). Selective evaluation and coping with stress: Making one’s situation cognitively more liveable. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25, 1499–1517.

Buunk, A. P., & Ybema, J. F. (1997). Social comparisons & occupational stress: The identification-contrast model. In A. P. Buunk & F. X. Gibbons (Eds.), Health, coping and well-being: Perspectives from social comparison theory (pp. 359–388). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Buunk, A. P., & Ybema, J. F. (2003). Feeling bad, but satisfied: The effects of upward and downward comparison with other couples upon mood and marital satisfaction. British Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 613–628.

Buunk, A. P., Ybema, J. F., Gibbons, F. X., & Ipenburg, M. (2001). The affective consequences of social comparison as related to professional burnout and social comparison orientation. European Journal of Social Psychology, 31, 46–55.

Buunk, A. P., Ybema, J. F., Van der Zee, K., Schaufeli, W. B., & Gibbons, F. X. (2001). Affect generated by social comparisons among nurses high and low burnout. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31, 1500–1520.

Buunk, A. P., Van der Zee, K. I., & Van Yperen, N. W. (2001). Neuroticism and social comparison orientation as moderators of affective responses to social comparison at work. Journal of Personality, 69, 745–763.

Buunk, A. P., & Van Yperen, N. W. (1991). Referential comparisons, relational comparisons, and exchange orientation: Their relation to marital satisfaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17, 709–717.

Buunk, A. P., Zurriaga, R., & González, P. (2006). Social comparison, coping and depression in people with spinal cord injury. Psychology and Health, 21, 791–807.

Buunk, A. P., Zurriaga, R., Gonzalez-Roma, V., & Subirats, M. (2003). Engaging in upward and downward comparisons as a determinant of relative deprivation at work: A longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 62, 370–388.

Buunk, A. P., Zurriaga, R., & Peíro, J. M. (2010). Social comparison as a predictor of changes in burnout among nurses. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 2, 181–194.

Buunk, A. P., Zurriaga, R., Peíró, J. M., Nauta, A., & Gosalvez, I. (2005). Social comparisons at work as related to a cooperative social climate and to individual differences in social comparison orientation. Applied Psychology. An International Review, 54, 61–80.

Callan, M. J., Kim, H., & Matthews, W. J. (2015). Age differences in social comparison tendency and personal relative deprivation. Personality and Individual Differences, 87, 196–199.

Carmona, C., Buunk, A. P., Peiro, J. M., Rodriguez, N. V., & Bravo, M. J. (2006). Do social comparison and coping styles play a role in the development of burnout? Cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 79, 85–99.

De la Sablonnière, R., Tougas, F., de la Sablonnière, E., & Debrosse, R. (2012). Profound organizational change, psychological distress and burnout symptoms: The mediator role of collective relative deprivation. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 15, 776–790.

DeVellis, R. F., Holt, K., Renner, B. R., Blalock, L. W., Cook, H. L., Klotz, M. L., et al. (1990). The relationship of social comparison to rheumatoid arthritis symptoms and affect. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 11, 1–18.

Dijkstra, P., Kuyper, H., Buunk, A. P., Van der Werf, G., & Van der Zee, Y. (2008). Social comparison in the classroom: A review. Review of Educational Research, 78, 828–879.

Exline, J., & Lobel, M. (2001). Private gain, social strain: Do relationship factors shape responses to outperformance? European Journal of Social Psychology, 31, 593–607.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations; Studies Towards the Integration of the Social Sciences, 7, 117–140.

Fickova, E., & Korcova, E. (2000). Psychometric relations between self-esteem measures and coping with stress. Studia Psychologica, 42, 237–242.

Fowers, B. J., Veingrad, M. R., & Dominics, C. (2002). The unbearable lightness of positive illusions: Engaged individuals’ explanations of unrealistically positive relationship perceptions. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 64, 450–460.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2006). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. In M. Csikszentmihalyi & I. S. Csikszentmihalyi (Eds.), A life worth living: Contributions to positive psychology (pp. 85–103). New York: Oxford University Press.

Frieswijk, N., Buunk, A. P., Steverink, N., & Slaets, J. P. (2004). The effect of social comparison information on the life satisfaction of older persons. Psychology and Aging, 19, 183–190.

Garcia-Izquierdo, A. L., Moscoso, S., & Ramos-Villagrasa, P. J. (2012). Reactions to the fairness of promotion methods: Procedural justice and job satisfaction. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 20, 394–403.

Garcia, S. M., Tor, A., & Schiff, T. M. (2013). The psychology of competition: A social comparison perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8, 634–650.

Gibbons, F. X. (1986). Social comparison and depression: Company’s effect on misery. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 140–148.

Gibbons, F. X., & Buunk, A. P. (1999). Individual differences in social comparison: Development of a scale of social comparison orientation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 129–142.

Gibbons, F. X., & Gerrard, M. (1989). Effects of upward and downward social comparison on mood states. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 8, 14–31.

Gibbons, F. X., & McCoy, S. B. (1991). Self-esteem, similarity, and reactions to active versus passive downward comparison. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 414–424.

Gilbert, P., Price, J., & Allan, S. (1995). Social comparison, social attractiveness and evolution: How might they be related? New Ideas in Psychology, 13, 149–165.

Hendrix, W. H., & Spencer, B. A. (1989). Development and test of a multivariate model of absenteeism. Psychological Reports, 64, 923–938.

Hoorens, V. (1995). Self-favoring biases, self-presentation, and the self-other asymmetry in social comparison. Journal of Personality, 63, 793–817.

Kuyper, H., Dijkstra, P., Buunk, A. P., & Van der Werf, M. P. (2011). Social comparisons in the classroom: An investigation of the better than average effect among secondary school children. Journal of School Psychology, 49, 25–53.

Marsh, H. W., Seaton, M., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Hau, K. T., O’Mara, A. J., et al. (2008). The big-fish-little-pond-effect stands up to critical scrutiny: Implications for theory, methodology, and future research. Educational Psychology Review, 20, 319–350.

McKenna, J. F. (1987). Equity/inequity, stress and employee commitment in a health care setting. Stress Medicine, 3, 71–74.

Meyer, H. H. (1980). Self-appraisal of job performance. Personnel Psychology, 33, 291–295.

Mohiyeddini, C., Bauer, S., & Semple, S. (2015). Neuroticism and stress: The role of displacement behavior. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 28, 391–407.

Morrell, B., Jordens, C. F. C., Kerridge, I. H., Harnett, P., Hobbs, K., & Mason, C. (2012). The perils of a vanishing cohort: A study of social comparisons by women with advanced ovarian cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 21, 382–391.

Reis, T. J., Gerrard, M. G., & Gibbons, F. X. (1993). Social comparison and the pill: Reactions to upward and downward comparison of contraceptive behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 19, 13–20.

Ross, L. L., & Bowen, A. M. (2010). Sexual decision making for the ‘better than average’ college student. Journal of American College Health, 59, 211–216.

Rusbult, C. E., Van Lange, P. A. M., Wildschut, T., Yovetich, N. A., & Verette, J. (2000). Perceived superiority in close relationships: Why it exists and persists. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 521–545.

Schachter, S. (1959). The psychology of affiliation: Experimental studies of the sources of gregariousness. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press.

Seyfarth, R. M., & Cheney, D. L. (2015). How sociality shapes the brain, behaviour and cognition. Animal Behaviour, 103, 187–190.

Sommer, K. L., & Baumeister, R. F. (2002). Self-evaluation, persistence, and performance following implicit rejection: The role of trait self-esteem. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 926–938.

Suls, J., Lemos, K., & Stewart, L. H. (2002). Self-esteem, construal, and comparisons with the self, friends, and peers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 252–261.

Suls, J., & Wheeler, L. (Eds.). (2000). Handbook of social comparison: Theory and research. New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Swap, C. W., & Rubin, J. Z. (1983). Measurement of interpersonal orientation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 208–219.

Tao, H. (2015). Multiple earnings comparisons and subjective earnings fairness: A cross-country study. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 57, 45–54.

Taylor, S. E., & Brown, J. D. (1988). Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 193–210.

Tennen, H., Eberhardt McKee, T., & Affleck, G. (2000). Social comparison processes in health and illness. In J. Suls & L. Wheeler (Eds.), Handbook of social comparison. Theory and research (pp. 443–483). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Tesser, A. (2000). On the confluence of self-esteem maintenance mechanisms. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4, 290–299.

Tomaka, J., Morales-Monks, S., & Shamaley, A. G. (2013). Stress and coping mediate relationships between contingent and global self-esteem and alcohol-related problems among college drinkers. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 29, 205–213.

Tummers, G. E. R., Landeweerd, J. A., & Van Merode, G. G. (2002). Work organization, work characteristics, and their psychological effects on nurses in the Netherlands. International Journal of Stress Management, 9, 183–206.

Van Oudenhoven-Van der Zee, K. I, Buunk, A. P., Sanderman, R., Botke, G., & Van den Bergh, F. (1999). The Big Five and identification–contrast processes in social comparison in adjustment to cancer treatment. European Journal of Personality, 13, 307–326.

Van der Zee, K. I., Bakker, A. B., & Buunk, A. P. (2001). Burnout and reactions to social comparison information among volunteer caregivers. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 14, 391–410.

Van der Zee, K. I., Buunk, A. P., De Ruiter, J. H., Tempelaar, R., Van Sonderen, E., & Sanderman, R. (1996). Social comparison and the subjective well-being of cancer patients. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 18, 453–468.

Van der Zee, K. I., Buunk, A. P., & Sanderman, R. (1996). A comparison of two multidimensional measures of health status: The relationship between social comparison processes and personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 22, 551–565.

Van der Zee, K. I., Oldersma, F., Buunk, A. P., & Bos, D. (1998). Social comparison preferences among cancer patients as related to neuroticism and social comparison orientation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 801–810.

Vogel, E. A., Rose, J. P., Roberts, L. R., & Eckles, K. (2014). Social comparison, social media, and self-esteem. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 3, 206–222.

Wood, J. V., Taylor, S. E., & Lichtman, R. R. (1985). Social comparison in adjustment to breast cancer. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 1169–1183.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Buunk, A.P., Dijkstra, P. (2017). Social Comparisons and Well-Being. In: Robinson, M., Eid, M. (eds) The Happy Mind: Cognitive Contributions to Well-Being. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58763-9_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58763-9_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-58761-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-58763-9

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)