Abstract

In this chapter, an overview of school counseling in Middle Eastern countries, namely, Egypt, Iran, Israel, and Turkey, is given. A brief history of school counseling in these countries is provided in order to understand current policy implementation, identify challenges and barriers to advancement, and address policy and research needs for the future development of the profession. This literature review revealed that unique larger societal events have impacted the development of the profession of school counseling in these countries over time. In addition, they have some commonalities with regard to challenges that the school counseling profession as a whole faces, such as the need for a clearer professional vision, a legislative process for the accreditation of school counselor training programs and school counselor licensure, policy-level solutions to alleviate high counselor-student ratio, and culturally relevant theories, measurement instruments, or techniques used in school counseling. Lastly, the Middle East is a conflict-prone region. Often, school-aged children are affected by war, internal violence, terrorist attacks, and political instability. Due to this fact, there is a need to train school counselors as qualified to respond to larger societal traumas. Although there is still room for improvement, the school counseling profession in these countries is promising and rapidly evolving.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- School-based Counseling

- Ministry Of National Education (MoNE)

- School Guidance Program

- Israelashvili

- Korkut

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

The aim of this chapter is to explore policy regarding school-based counseling in Middle Eastern countries, namely, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Israel. These countries were chosen because each represents a unique culture within the Middle Eastern region and has relatively more developed school-based counseling services than the rest of the region. Turkey will be examined more closely, since the author is of Turkish origin, and it was therefore possible to access more research articles in both Turkish and English. A brief history of school counseling in these countries will be provided in order to understand current policy implementation, challenges and barriers to advancement, and policy and research needs for the future development of the profession.

A Brief History of School Counseling in Turkey

The modern Republic of Turkey was established in 1923 after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. Turkey is located at the meeting point of Europe and Asia and is considered a bridge between the two continents. Turkey has been a candidate for European Union (EU) membership since 1999. Although some notable progress has been made in the last two decades, full membership in the European Union has not yet been achieved. Turkey is a secular democratic republic, in which the majority of people are Muslim. Today, Turkey has a population of 77,695,904 (Turkish Statistical Institute [TUIK], 2014). Turkey has a relatively young population – the median age is 30.7 (TUIK, 2014), and school-aged children comprise 22.6% of the total population. Education is compulsory in Turkey until the 12th grade and kindergarten is not part of compulsory education.

School counseling as a profession in Turkey began as early as the 1950s, in parallel with Turkey’s rapprochement to the United States between 1945 and 1950 . During that time period, the United States supported Turkey through the Marshall Plan. As a part of the Marshall Plan, educational exchanges between the two countries were promoted (Pişkin, 2006; Yeşilyaprak, 2009). Hence, counselor educators from the United States visited Turkey in 1950 and conducted a series of seminars on the concept of counseling during their visit (Doğan, 2000). In the following years, experienced educators were sent to the United States to study counseling through the Ministry of National Education (Doğan, 2000). Therefore, it is possible to say that the development of school counseling in Turkey was influenced by American theories and practices (Doğan, 2000; Korkut-Owen, Owen, & Ballestero, 2009). During the mid-1960s, both graduate and undergraduate counseling programs were established in some Turkish universities.

The 1970s was considered a “golden era” of school counseling in Turkey (Doğan, 1998). Two events had a profound impact on the development of school counseling during this period. First, 90 school counselors were employed for the first time in 24 secondary schools between the years of 1970 and 1971. Second, the Ministry of National Education (MoNE) took a step toward establishing counseling services countrywide at the secondary school level and decided to provide two counseling hours weekly for each grade level during the 1974–1975 academic year (Doğan, 1998). In 1996, MoNE also started to employ school counselors in elementary schools for the first time (Doğan, 2000). From this time forward, school counseling in Turkey has been mandatory at all grade levels.

The 1980s in Turkey witnessed a rapid increase in the number of undergraduate and graduate programs in counseling (Doğan, 1998). In 1989, the Turkish Psychological Counseling and Guidance Association (TPCGA) was founded. Following its foundation, it began to take a proactive role in improving the quality of the profession in the country. It began by publishing the Journal of Counseling and Guidance in 1990 and Psychological Counseling and Guidance bulletin in 1997. It also held the first National Psychological Counseling and Guidance Congress in 1991 and outlined ethical standards of the profession in 1995 (Doğan, 2000). The Turkish Psychological Counseling and Guidance Association still plays a notable role in advocating school counseling. Another effort to advocate for the profession was established by school counselor institution’s department chairs. They began to hold nationwide yearly meetings in 2000 to discuss the problems faced in the school counseling field and to lobby for practices and policies that enhance the profession (Korkut, 2007; Stockton & Güneri, 2011).

Thus far, noteworthy milestones in the progress of Turkish school counseling (from its inception until the end of the 1990s) have been briefly introduced. In the following section, detailed information about current policy, practice, and research in the field of school counseling in Turkey will be discussed, starting from the 2000s.

School Counselor Education in Turkey

School counselors in Turkey are trained at undergraduate level. School counseling preparation programs , often termed “Guidance and Psychological Counseling,” are housed in the Department of Educational Sciences, with Departments of Education. Undergraduate programs in “Guidance and Psychological Counseling” are designed primarily to train practicing school counselors to meet public schools’ needs in the nation (Korkut, 2007). However, upon completion of 4 years of undergraduate study, students are awarded the title of “guidance teacher,” rather than “school counselor” or “psychological counselor.”

The debate as to which title graduates should be authorized under has been ongoing since the 1990s. The Turkish Psychological Counseling and Guidance Association and program leaders have been involved in advocacy efforts to change the professional title from “guidance teacher” to “psychological counselor” on graduates’ diplomas since 1997 (Pişkin, 2006). They argue that the specialty title of “guidance teacher” led to misunderstandings of the counselor’s role in schools, since the term “teacher” assumes more responsibility for teaching and discipline. In addition, this title restricts the scope of work opportunities for graduates to only schools, even though they should be allowed to apply for and be recruited by not just the Ministry of Education but also the Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Health, and Ministry of Family, due to the need for counselors in these fields.

Turkey has a very centralized educational system. The Turkish Higher Education Council (HEC) is the only authority that regulates higher education policies and all higher education institutions tied to the HEC . In 2007, with the aim of standardization of counselor education programs throughout the nation, the HEC mandated a uniform curriculum for all school counseling training programs across the country, without soliciting sufficient input from the counselor educators (Korkut-Owen & Güneri, 2013). Although the need for uniformity in counselor education had already been discussed in school counseling literature before 2007, the HEC’s requirement aroused indignation among academics as their voice was ignored (Stockton & Güneri, 2011). This new national curriculum was criticized by counselor education program leaders, since it was not designed to ensure school counselor competencies (Poyrazlı, Doğan, & Eskin, 2013), but rather it was based on areas of competency designed for teachers (Stockton & Güneri, 2011). As of 2016, redesigning of school counseling training curriculum has again taken HEC’s agenda, and new changes are expected yet not announced officially.

Weak communication and management between MoNE and HEC also creates some complicated situations in terms of school counselors’ training. For instance, while HEC determines the curriculum for school counselor education programs, MoNE sets the role and functions of school counselors. Their decisions are often disparate, since close unitary alignment between these governmental units is insufficient. Additional collaborative efforts are needed in order to make sure that school counseling policies are aligned and a variety of key stakeholder’s voices heard at each stage of the policy development process.

In addition to the lack of alignment with MoNE guidelines , HEC’s mandated curriculum is also criticized as not creating an inclusive and multicultural counseling course, even though Turkey has a diverse population (Bektaş, 2006; Kağnıcı, 2011). Furthermore, although it is argued that the applied clinical courses and supervision during counselor training programs are not sufficient to help students develop necessary skills for practice (Korkut, 2007), limited research exists regarding the supervision practices of school counselors in training (Aladağ, 2013).

Some common core courses in the HEC curriculum include: Theories of Counseling; Individual, Group, and Career Counseling; Ethics; Psychological Testing; Cognitive Psychology; Abnormal Psychology; Developmental Psychology; Research Methods; Statistics; Measurement and Evaluation; Classroom Management; Teaching Principles and Methods; Curriculum Development; and the History of Turkish Education and Educational Management (HEC, nd).

There are currently 70 public and foundation universities that offer undergraduate degrees in Guidance and Psychological Counseling (Turkish Council of Higher Education Student Selection and Placement Center, 2015). Guidance and Psychological Counseling undergraduate programs accept students based on a two-staged central examination held by the HEC’s Center for Student Selection and Placement (CSSP). In 2015, 6108 students placed in Guidance and Psychological Counseling undergraduate programs (author’s calculations based on Turkish Council of Higher Education Student Selection and Placement Center, 2015). There are 602 faculty members (113 full professors, 110 associate professors, 379 assistant professors) employed in Guidance and Psychological Counseling programs (author’s calculations based on Turkish Council of Higher Education Student Selection and Placement Center, 2015).

As of 2011, 21 universities offer master’s and 14 offer doctorate degrees in Guidance and Psychological Counseling (Korkut-Owen & Güneri, 2013). As stated above, undergraduate “Guidance and Psychological Counseling” programs are specifically designed to train school counselors and graduates to achieve the title of “guidance teacher.” On the other hand, master’s and doctorate degrees are more generic to the field of counseling (Korkut, 2007), and there are currently no specializations in graduate programs (e.g., Mental Health Counseling; Marital, Couple, and Family Counseling; Career Counseling; Rehabilitation Counseling; etc.) with the exception of two universities, which offer specialized training in career counseling in their Business and Human Resources departments (Korkut-Owen & Güneri, 2013). Currently, training at master’s level is seen as an “intermediate step toward doctoral work” or as a prerequisite to obtain work as an “administrator of guidance services.” In addition, “a doctoral degree is necessary to become a counselor educator or a consultant for the Ministry of National Education” (Korkut, 2007, p. 14).

The level of training needed (e.g., undergraduate degree or graduate degree) in school counselor preparation has been an ongoing debate for a long time in Turkey. Some argue that undergraduate degrees in school counseling are necessary to avoid a school counselor shortage (Akkoyun, 1995; Doğan, 2000) (currently, it is estimated that number of school counselors will soon exceed the hiring capacity of MoNE).

In Turkey, the Department of In-Service Training in the Ministry of National Education is responsible of providing professional development needs of educators in public school system including school counselors in practice. Until 1993, in-service trainings had planned and delivered as centrally (nationally); however, this system was found to be inefficient in many ways. Therefore the MoNE delegated this responsibility to the local national educational directories at 1993 to be able to better identify the in-service training needs of local teachers and make it more feasible in terms of the budget (Bayrakcı, 2009), although there are still insufficient school counselors in practice, both related to the quantity and quality of in-service training provision (Sezer, 2006). Recent research revealed that practicing school counselors’ top four professional development needs are bullying prevention and intervention programs, conflict management education in schools, preventing sexual harassment, and cyberbullying and inclusive education (Köse Şirin & Diker Coşkun, 2015).

Program Accreditation and School Counselor Licensure in Turkey

As stated, HEC-mandated uniform curriculum for school counselor preparation programs was introduced without a concrete definition of core competencies of school counselors. This regulation only created unity in course titles and credit/hours, not in content (Poyrazlı et al., 2013). Due to this policy and practice gap, school counselor training institutions lack a common understanding of student knowledge and skills outcomes, course characteristics, and content change from one university to other (Akkoyun, 1995; Aladağ, 2013; Doğan, 2000; Korkut, 2007). Given the variation that exists in school counselor training, defining training standards for school counselors and building an accreditation body for counselor education seems an important policy action for the development of the profession.

The discussion of a need for professional standards and accreditation of school counselor training programs has been continually promoted by TPCGA and program leaders since 1995 (Korkut, 2007; Korkut & Mızıkacı, 2008); however, there have been no concrete steps taken yet. Korkut and Mızıkacı (2008) argue that Turkey’s integration of the Bologna Declaration, which aims to create a common understanding and the ability to transfer qualifications in higher education within European countries, might be the force needed to drive the setting of standardized criteria for school counselor training.

There are also no licensure requirements for school counselors in Turkey. Most Guidance and Psychological Counseling program graduates are employed by MoNE and work in educational settings (Korkut-Owen & Güneri, 2013). MoNE regulates recruitment of school counselor candidates. Those who wish to serve as school counselors in public K-12 schools are required to take a central and highly competitive exam called the Civil Service Personnel Selection Exam and are appointed by MoNE based on test scores. This policy began in 2002. Nevertheless, this exam is not considered a licensure examination for counselors since it is a generic examination for anyone who wants to work in civil service .

Need for School Counselors in Turkey

As of November 2014, 27,798 school counselors work in the Turkish public K-12 education system . Considering that there are about 17.3 million students in formal education in Turkey, the school-counselor-to-student ratio is about 650 (Education Reform Initiative, 2015). Based on 2011 statistics, MoNE actually needs 38.556 school counselors in total, which means 19,728 more counselors are needed to meet the shortage (TPCGA, nd). However, currently vacant positions cannot be filled because of the school counselor shortage and budgetary concerns of MoNE . In the latest report of the Education Reform Initiative, it is stated that “MoNE is aware of the shortage of school counselors; a significant portion of teacher appointments in 2014 were carried out in the counseling field. However, the school counselor shortage continues, and it is essential that MoNE continues to address this issue” (Education Reform Initiative, 2015, p. 13). In spite of this awareness, however, this problem continues.

Since there has been a school counselor shortage for years, MoNE has recruited nonschool counseling degree graduates with insufficient training in order to avert this shortage. However, with the rapid increase in the number of counselor training programs countrywide in recent years, it is estimated that in the near future the supply of school counselors will soon exceed the recruitment capacity of MoNE. At the latest yearly regular department chairs’ meeting, it was decided to initiate lobbying efforts in an effort to decrease the quota of school counseling training programs.

Despite all of these facts, MoNE still continues to recruit nonschool counseling degree graduates and is strongly criticized by the Turkish Psychological Counseling and Guidance Association, since this disadvantages new school counseling graduates and also negatively impacts the profession’s reputation. According to 2011 statistics, out of 18,828 school counselors who work in public schools, only 13,419 of them hold a degree in school counseling, and the rest of them were recruited from other majors such as philosophy, sociology, and psychology (TPCGA, 2011). The lack of MoNE’s national plan in terms of workforce planning of school counselors is a significant problem (Yeşilyaprak, 2012). There should be a nationwide needs assessment in order to develop sound strategic planning. If this issue is not controlled in a strategic manner, there is the risk of continuing uncoordinated policy responses to school counselor workforce challenges.

The Role and Functions of School Counselors in Turkey

MoNE (2001) defined the functions of school counselors through a document entitled “The MoNE Guidance and Psychological Counseling Services Regulation.” In this document the functions of school counselors were defined in 19 items (Article 50). The following activities were deemed appropriate for school counselors: collaborating with teachers to present guidance lessons, ensuring student records are maintained as related to guidance service ; designing guidance and counseling programs based on schools’ needs; providing individual counseling services to students; planning educational and career guidance activities, implementing them or guiding other teachers in implementation; guiding students with special needs and their families within the collaboration of Provincial Guidance and Research Centers (GRCs); organizing meetings, conferences, or panels for parents, students, and teachers; evaluating guidance and counseling activities at the end of the school year; and preparing an evaluation report.

In the same regulation , inappropriate activities for school counselors to partake in were also delineated (Article 55). Included in the list of inappropriate activities were the following: substituting for absent teachers, performing clerical and administrative duties, hall monitoring, and acting as an invigilator. Although addressing school counselors’ appropriate and inappropriate job functions in a formal government regulation might give power to practitioners in performing their job, these guidelines have been found to be vague by many academicians (Korkut, 2007; Korkut-Owen & Owen, 2008) since these tasks and major functions were not dependent on clearly defined role descriptions. Besides that, since this regulation was put into practice in 2001 before the infusion of a comprehensive approach to school counseling, it is thus questionable whether defined functions of school counselors in this regulation meet the functions of school counselors with respect to preventative and comprehensive developmental perspectives.

In Turkey, all undergraduate students who study for any degree in an education faculty have to take a course focusing on the practice of guidance counseling before graduation (HEC, 1997). This requirement may help to educate future teachers and principals in developing a greater appreciation for the roles and responsibilities of school counselors. However, there is no research on how this course shapes future educators’ understanding of school counselors’ role and functions nor overall school counseling services. Due to this fact, this mandatory course can be interpreted as an indicator of the essential value of school counseling services (Korkut-Owen et al., 2009).

Along these lines, several recent studies were conducted to determine principals’ and teachers’ perceptions of the responsibilities of school counselors. For example, Korkut-Owen and Owen (2008) found similar patterns of role expectations and valued counselor activities between school counselors and school principals, both of which placed less emphasis on administrative duties as school counselor functions. In contrast, some other studies revealed that school principals do not have sufficient knowledge of the scope and the purpose of counseling services (Nazlı, 2007) and they continue to perceive administrative and clerical tasks, and substitute teaching, as functions of the school counselor (Aydın, Arastaman, & Akar, 2011).

In recent years, the leadership (Köse, 2015) and advocacy role of school counselors has also opened up for discussion in school counseling literature (Gültekin, 2004; Keklik, 2010). The debate about the role and main functions of school counselors is likely to continue in the future.

Lastly, the Provincial Guidance and Research Centers (GRCs) plays an important role in providing school counseling services in Turkey. GRCs are governmental units tied to MoNE and available in each province. Their main function is to carry out special education services, deliver some counseling services to schools that lacked school counselors, and provide extra support to counseling services to schools in the region (Korkut-Owen & Güneri, 2013).

A National School Guidance Program in Turkey

One major recent development in school counseling in Turkey was the adoption of a comprehensive developmental school guidance program in 2006. This program aims to position school counseling services as an integral part of the school mission and place school counselors in proactive role to serve all students, not just those with mental health needs. With the adaptation of a national scheme for school counseling services, school counselors are required to meet the needs of students in educational, career, and personal/social domains, and a focus on preventive and developmental counseling in schools has gained importance (Ergüner-Tekinalp, Leuwerke & Terzi, 2009; Korkut-Owen et al., 2009).

The American School Counselor Association (ASCA) National Model was taken as a template in the preparation of this comprehensive developmental school guidance program for Turkish schools (Nazlı, 2006). Prior to its current model, this program was piloted in some curriculum laboratory schools between 2000 and 2003 (Nazlı, 2006). Since the pilot study produced positive outcomes, such as increased study skills, adaptation skills, decision-making and problem-solving skills of students, and positively affected students’ acceptance of self and career development (Nazlı, 2006), the comprehensive developmental guidance concept was consequently extended to all elementary and secondary schools countrywide in 2006 (Ergüner-Tekinalp et al., 2009; Korkut-Owen et al., 2009). Part of this effort, a framework program called “Elementary and Secondary Class Guidance Curriculum” was developed by MoNE and was implemented in 2006.

Starting from 2006, the MoNE Board of Education gradually added one mandatory “guidance hour” to the overall curriculum at all education levels, and classroom teachers were made responsible for delivering classroom guidance lessons with the collaboration of school counselors, in line with the “Elementary and Secondary Class Guidance Curriculum” of MoNE (the term “guidance hour” instead of “guidance class” was chosen so that it would not be perceived as a regular lesson) (MoNE, 2006). This implementation was widely considered a positive gain for the profession and forms the backbone of the comprehensive developmental guidance program (Şensoy-Briddick & Briddick, 2015). However, Turkey had a major policy reform in the education system during the 2012–2013 academic years. Compulsory education was extended from 8 years to 12 years and divided into 4 years elementary, 4 years middle, and 4 years high school education (publically called as 4 + 4 + 4 system). In this way, religious schools have become optional for the middle school stage of education. As part of this policy reform, a number of elective courses (religious elective courses added) were also increased in the national public school curricula. To be able to open up a place to newly added elective courses, mandatory guidance hours were eventually abandoned by 2015 in elementary and middle schools (MoNE, 2014). The removal of guidance hours that were previously part of the general school curriculum jeopardized the implementation of a comprehensive developmental approach. Instead, the 1-h mandatory “Guidance and Career Planning Lesson” was added to the overall curriculum only for students in grade eight, and classroom guidance teachers were tasked to teach this lesson in line with the framework program provided by MoNE (MoNE, 2014). Classroom guidance activities still continue at high school level as part of “Secondary Schools Guidance and Orientation Lesson” (MoNE, 2011).

A recent study revealed that this shift in the Turkish education system from a traditional guidance model to a comprehensive developmental school guidance model has been embraced by school counseling practitioners , since it provided explicit goals for the school counseling program, made school counselors’ role definition more clear, and opened up a method of collaboration with teachers (Terzi, Ergüner-Tekinalp, & Leuwerke, 2011). On the other hand, there have been some challenges to successful implementation. Some of these challenges include a high student-counselor ratio (Nazlı, 2006; Ergüner-Tekinalp et al., 2009; Demirel, 2010); some deficiencies in counselor education programs, such as graduates who are not trained to implement a preventive, developmental counseling program (Ergüner-Tekinalp et al., 2009); availability of evidence-based preventive curriculums or group interventions for use by counselors (Köse Şirin & Diker Coşkun, 2015); and classroom teachers with insufficient training in delivering guidance lessons (Demirel, 2010; Siyez, Kaya, & Uz Bas, 2012; Terzi et al., 2011). All of these have been highlighted as some of the significant difficulties faced in trying to implement a comprehensive developmental guidance program in Turkey.

Although a comprehensive developmental approach to school counseling has been implemented in Turkey since 2006, there is no clearly defined national model in which the mission, role, and functions of school counselors or service delivery components are thoroughly considered. The existing model is more like a framework curriculum that gives structure for school-based counseling services.

Research that evaluates the impact of a comprehensive developmental school guidance program is very limited, although empirical evidence showing the benefits of this program is needed (Ergüner-Tekinalp et al., 2009; Stockton & Güneri, 2011). In addition to this, the model has been criticized, since the program has not been revised nor improved since 2006. Also, as stated earlier, recent removal of classroom guidance lessons from the overall national public schools’ curricula is thought provoking in terms of future of comprehensive school counseling programs in Turkey. Education policy in Turkey is highly controversial, incredibly polarized, and a debated issue in society that lasts a couple years. It is argued that current government, as part of their political agenda, implicitly implements policies to shape both the content and structure of education system more religious at the expense of secular academic schooling. In such current sociopolitical environment, it is getting challenging to agree to a common vision about what school counseling programing should address at the national level.

Refugees and School Counseling in Turkey

Currently, the Syrian refugee issue is one of the most debated topics in Turkey. More than 4 million refugees from the Syrian Civil War have left their home country since the start of the war, and Turkey has taken in the largest number of Syrian refugees of any country in the world. Nearly 2.5 million Syrians have taken refuge in Turkey since 2011 (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHRC], 2016), and of those, more than 1.7 million live in refugee camps (Darcy et al. (2015) Close to half of these are children under the age of 17 (UNHRC, 2016). As of the 2014–2015 academic year, 150,000 Syrian students have been integrated into the Turkish education system (Istanbul Bilgi University Children Study Unit [ÇOÇA], 2015). Many of these students have experienced psychological difficulties, such as symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), since they were exposed to violence in Syria, and further stressors, such as poverty after immigration and difficulties integrating into a new culture, all of which make their situation worse (ÇOÇA, 2015).

A recent study noted that these students underutilize school counseling services, and school counselors do not offer any interventions for them, since they feel either inadequately resourced or skilled to serve this population. High counselor-student ratios and language barriers are also highlighted as factors that negatively impact the school counselor’s ability to help this population of students (ÇOÇA, 2015).

Considering that there are also other refugee populations, totaling approximately 36,000 individuals, from countries such as Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, and Somalia, the education and mental health needs of refugee students should be taken seriously (Şeker & Aslan, 2015). The MoNE should provide support for school counselors (e.g., handbooks, in-service training) to equip them with the knowledge and skills to help these students in a school setting, and more school counselors should be appointed to those schools where there is a high occurrence of refugee students.

Egypt

School counseling services in Egypt are delivered by “psychological professionals,” and their utilization is mandatory in schools (Mikhemar, 2013). The term “psychological professionals” has been found to be problematic since it does not reflect the professional identity of school counselors. Although mandatory, many public schools lack counseling services due to a shortage of qualified professionals and budgetary concerns of the Ministry of Education. Based on Ministry of Education data from 2011, the total number of “psychological professionals” in middle and high schools was 9,082 and the demand for school counselors in that same year was 31,736 (Mikhemar, 2013). Results from a study found an overall statewide student-to-counselor ratio of 3080:1, and in the same study, it was estimated that the population of Egypt would surpass 83 million and rise to 100 million by the year 2025 (Jimerson, Alghorani, Darweish, & Abdelaziz, 2010). All this data reveals that insufficient numbers of school counselors will become an important issue that negatively impacts the quality of school counseling services in Egypt, unless the Ministry of Education takes action to eliminate the shortage.

School counselors in Egypt generally graduate from Psychology Departments that are housed in Colleges of Arts (Amer, 2013). There is no higher education institution that offers specialization in school counseling (Amer, 2013; Mikhemar, 2013). Therefore, a mental health model of counseling is the primary focus of counseling services in schools, and counseling, consultation, direct interventions, primary prevention, and psychometric assessments (e.g., intelligence tests) are reported to be the main work activities of school counselors (Jimerson et al., 2010).

It is pointed out in the literature that non-counseling tasks, such as clerical and administrative duties, take up much of a counselor’s time and the profession faces role disparity and unclear responsibilities , which lead to the underestimation of counselors’ functions in the schools (Jimerson et al., 2010; Mikhemar, 2013). In addition, insufficient resources (Jimerson et al., 2010) and the government’s unfair payment policies for school counselors (Mikhemar, 2013) are also highlighted as significant problems that negatively impact the profession.

There are two psychological associations in Egypt, namely, the Egyptian Association for Psychological Studies and the Egyptian Psychologist Association (Jimerson et al., 2010); however, there is no professional association for counseling nor school counseling (Mikhemar, 2013). The counseling profession in Egypt is not considered a unique and distinct discipline from psychology (Amer, 2013; Mikhemar, 2013); therefore, the profession faces an identity crisis. Amer (2013) asserts that “the roles of school versus clinical psychologist are sometimes contested and psychological practice is often conflated with social work or psychiatry” (p. 26). As it is not seen as an independent profession, there is no national system of certifying school counselors (Amer, 2013).

Research on school counseling in Egyptian literature is limited. The lack of funding resources for scholars and language barriers impede the advancement of research. It is pointed out that even if there is some valuable published research on counseling, it is not widely read internationally due to the limited language ability of the Egyptian researchers and therefore their inability to publish in Western journals (Amer, 2013; Mikhemar, 2013).

Political instability, overpopulation, within-country immigration, and poverty are the main social problems in Egypt. These socioeconomic hardships have had many consequences for school-aged children (Amer, 2013). For example, one recent research report shows that during the Egyptian political conflict (the so-called Arab Spring) children whose schools were located close to the main conflict areas (Tahrir Square) suffered from depression, PTSD, and anxiety symptoms, since they witnessed considerable violence (Moussa et al., 2015). Nevertheless, resources to support these students are limited. It can be concluded that these issues should be addressed in school counseling policies in Egypt. Lastly, the need for culturally appropriate approaches in counseling is also highlighted as an issue that should be shown attention in the future, since Western Models do not always fit the religio-cultural context of Egypt (Amer, 2013).

Iran

The history of school counseling in Iran started in the 1960s when the Iranian Ministry of Education sent a group of local experts to Western countries such as the United States, Canada, and England to study counseling and related fields. These experts established and developed the counseling profession when they returned from abroad (Fatemi, Khodayari, & Stewart, 2015).

Following their inception, in 1967, the first counselor education programs were opened at both the undergraduate and master’s levels in Departments of Education and Psychology at Tehran’s Tarbiat Moallem University. Starting in 1986, a number of counselor education programs were developed in Tehran and also doctoral level studies became available (Korkut-Owen, Damırchı, & Molaei, 2013). A notable event occurred in 1971 when school counseling first started to be implemented at middle school level. Efforts to increase school counseling services in the education system were accelerated, mostly in middle schools, starting from 1985 (Korkut-Owen et al., 2013). Currently, school counseling is mandated for secondary schools in Iran (Harris, 2013), and there has been no updated information collected about the school-counselor-to-student ratio. However, Harris (2013) states that there are not enough trained counselors for every school in Iran, especially in rural areas.

A School Counseling degree is offered at undergraduate, master’s, and doctorate levels in Iran in the Departments of Psychology and Education. There are 18 undergraduate, 15 master’s, and 5 doctoral level programs currently available in the country. While most universities offer a generic psychological counseling degree, in some of them, school counseling is offered as a distinct specialization (Korkut-Owen et al., 2013). As the Iranian education system is centralized, the Ministry of Science and Technology has begun to regulate the curriculum of counseling programs at all levels (Korkut-Owen et al., 2013). Counselor training programs are criticized, since many of the concepts and theories taught in these programs have been adopted from Western countries without critically evaluating whether they are culturally relevant to Iranian society (Birashk, 2013; Fatemi et al., 2015).

Iranian school counselors (officially termed “consultants”) are expected to provide educational counseling, preventive counseling, career planning, and individual/group counseling for students who need special attention (Fatemi et al., 2015). They encounter some problems, which impede their effectiveness. First, other school employees are not fully aware of the professional roles of counselors (Fatemi et al., 2015). Second, they lack necessary valid measures when working with students, such as interest inventories, among others (Alavi, Boujarian, & Ninggal, 2012; Fatemi et al., 2015). Third, they don’t have enough in-service training opportunities to improve their counseling knowledge and skills (Alavi et al., 2012). Lastly, nonschool counseling graduates are appointed to school counselor positions due to scarce numbers of counselors, and this is considered one of the biggest challenges for the profession (Korkut-Owen et al., 2013). Further studies are needed to identify the barriers and problems of school counseling in Iran (Alavi et al., 2012).

In 1988, the Iranian Psychological Counseling Association (IPCA) was chartered. This association serves to advocate for the counseling profession, creating international connections and promoting research in the field. Also, the IPCA monitors and gives work licenses to psychological counseling clinics (Korkut-Owen et al., 2013). Although private practitioners in counseling are required to obtain licensure, there is no such regulation for school counselors (Fatemi et al., 2015).

Fatemi et al. (2015) state that larger societal events such as the Iran-Iraq war, which continued for 8 years, and large-scale natural disasters such as the Tehran earthquake of 1990 increased the demand for counseling services in Iran. Currently, a prevalence of substance abuse among adolescents, high youth unemployment rates, and Iranian youths’ struggles in seeking a balance between Western and traditional values (Fatemi et al., 2015) are cited as common societal concerns. How national school counseling policy guidelines aim to address these large-scale social issues was beyond the scope of this work.

Israel

The school counseling profession was actively integrated into the Israeli education system during the early 1960s when 34 school counselors (officially termed “teacher counselors”) were appointed to different public schools (Karayanni, 1996). Since then the number of school counselors has increased rapidly, and currently there are about 4300 school counselors working in Israeli schools (Israelashvili, 2013) and the student-counselor ratio is approximately 1:570 (Erhard & Erhard-Weiss, 2007; Harris, 2013). School counselors are required in all educational settings in Israeli schools (Israelashvili, 2013).

School counseling in Israel has been influenced by the American counseling tradition. In the formative years of school counseling, the American School Counseling Association’s (ASCA ) approach was taken as a guide while establishing the school counselor’s role and the main functions of school counseling services in Israel (Rantissi, 2002). When school counseling first entered into the education system in the 1960s , it was perceived as a means of addressing the vocational needs of students, assisting disadvantaged pupils to improve their learning (Karayanni, 1996) and responding to the mental health needs of high-risk students (Erhard & Harel, 2005). During the 1980s, a need for redefinition of the function of school counseling services arose, since the remedial focus of counselors was considered ineffective, as they spent the majority of their time working with limited numbers of students rather than devoting their efforts to improving the whole school system (Rantissi, 2002). Therefore, in the 1980s, the focus of school counseling shifted from individual guidance and counseling to primary prevention (Erhard & Harel, 2005). From that time to the current day, the role of the school counselor in Israel has transformed to address the developmental needs of all students (Erhard & Harel, 2005), and currently, the ideal approach to school counseling is considered developmental, preventive, and systems-oriented (Klingman, 2002). Erhard and Harel (2005) state that “[t]he profession in Israel as in many other countries is being transformed from various marginal, ancillary and supplemental services to comprehensive counseling that is integral to the total school education program” (p. 87).

Recent research conducted with 681 school counselors in Israel revealed that 40% of the counselors in the sample allocated a greater amount of their time to direct individual counseling to students and focused on crisis and remedial counseling, whereas 20% of the counselors mainly focused on preventive activities through classroom guidance or small group counseling, and finally 40% of them equally divided their time between remedial and preventive counseling (Erhard & Harel, 2005). Frequent paradigm shifts (individual intervention versus systemic orientation and prevention versus remediation) in the understanding of the school counseling profession are considered one of the causes of role confusion concerning school counselors in Israel (Shimoni & Greenberger, 2014). It is also stated in the Israeli literature that the use of counselors for non-counseling tasks is prevalent and this has also exacerbated the difficulty in clarifying the professional roles (Shimoni & Greenberger, 2014). Standards for the Professional Practice of School Counseling, which were prepared based on ASCA National Standards for School Counseling, were published in Israel in 2009 (Shimoni & Greenberger, 2014). This development is promising in terms of resolving the tension over ideal professional roles (Shimoni & Greenberger, 2014).

Besides their myriad and disparate responsibilities , the unique needs of Israeli society have also impacted the roles of Israeli school counselors. For example, responding to war-related trauma of students is considered one of the main responsibilities of Israeli school counselors (Israelashvili, 2013), as Israel has been involved in several major armed conflicts since it was established in 1948. As schools are considered the major source of social support and a facilitator of recovery (Abel & Friedman, 2009), school counselors are expected to debrief the children when cities are under attack and enable them to interact with one another in order to seek social support and help conflict-affected pupils (Israelashvili, 2013). In addition, when violent political conflict occurs, they are considered the main actor in the schools in taking a leading role in “consultation [with] school administrators and educators with regard to their difficulties in conducting situation-relevant classroom discussions and handling pupils’ stress reactions” (Klingman, 2002, p. 248). They are also “encouraged to educate students and advocate their participation in the ongoing peace process” (Abel & Friedman, 2009, p. 267). Due to these realities of the profession, it is not surprising that war-related literature and research in school counseling in Israel is prevalent and crisis intervention is emphasized in almost all school counseling preparation programs (Karayanni, 1996).

Another unique aspect of Israeli society, which also affects the roles of school counselors, is its identity as a multiethnic, multiracial, and multi-religious society. Israel is considered the homeland of Jews the world over and therefore accepts many immigrants who have connections to Judaism (Israelashvili, 2013). Also, about 20% of Israel’s population is composed of Palestinian Arabs. School counselors are expected to deal with the specific needs of immigrant children who come from different racial and ethnic identities (Karayanni, 1996). Even in the 1990s, when nearly a million immigrants from the former Soviet Union arrived in Israel, schools provided extra counseling hours for this purpose (Karayanni, 1996). Related to this issue of diversity in Israeli society, Tatar and Horenczyk (2003) argue that “[t]hree main areas seem to become pivotal in the professional agenda of Israeli school counselors in the 21st century: working with multicultural populations; implementing conflict resolution strategies, especially for dealing with violence and antisocial behavior; and developing a systemic self-awareness as agents for social action and change” (p. 378). It is also noted in the literature that building multicultural competencies in school counselor trainees is essential in Israel, since schools are culturally heterogeneous institutions (Erhard & Sinai, 2012; Horenczyk & Tatar, 2004; Tatar, 2012; Tatar & Horenczyk, 2003) and counseling of immigrants and students from minority groups should receive more attention (Horenczyk & Tatar, 2004).

School counseling training is generally offered at graduate level within schools of education (Israelashvili, 2013; Lazovsky & Shimoni, 2007). As of 2012, six universities offer graduate degrees (master’s and doctoral) in school counseling (Israelashvili & Wegman-Rozi, 2012). After graduation, school counselor’s in-service training continues under the supervision of their municipal counseling inspector (Israelashvili, 2013). Currently, in Israel, there are no state laws and regulations for licensure on professional school counseling. Despite a great deal of effort having been put in by the Israeli Association of School Counselors, these efforts have failed (Israelashvili & Wegman-Rozi, 2012).

Integrative Summary and Concluding Remarks

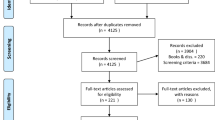

In this chapter, an overview of school counseling in Middle Eastern countries, namely, in Egypt, Iran, Israel, and Turkey, is given. This literature review revealed that the profession of school counseling in these countries is promising and rapidly evolving. In addition, they have some commonalities with regard to challenges that the school counseling profession as a whole faces. Table 25.1 summarizes some aspects of school counseling in these four countries.

First of all, the school counseling profession in these countries struggles to establish a clear professional identity . With the exception of Egypt, comprehensive developmental counseling models are considered the best approach to school counseling, although there are no written national models that reflect the unique cultural and organizational needs of these societies. Developing national school counseling program models would shape the professional identity of school counselors, so that they might have a clearer professional vision and ground their identity based on these national models. Related to this identity issue, the variety of titles that has been used for school counselors in Middle Eastern countries is noteworthy. Considering that professional titles frame implicit and explicit assumptions about the scope of professional practice and professional identity, disparate and often confusing titles should be universally replaced by the title “school counselor.”

Secondly, there are no accreditation standards or counselor certification requirements in these countries. A strong initiative is needed to create a legislative process for the accreditation of school counselor training programs and school counselor licensure.

Thirdly, in Middle Eastern countries, there is a clear need to develop culturally relevant theories. Equally, measurement instruments and techniques used in school counseling have been cited as especially important areas for researchers to focus on and develop. Since the emergence of school counseling started with the significant impact of the Western model in Middle Eastern countries, many theoretical approaches and models in counseling were imported from the west without any consideration of cultural adaptation. There is a strong need to assess their cultural validity and limitations.

Fourthly, high school-counselor-to-student ratios and nationwide school counselor shortages are another significant problem in all these countries. Policy solutions used to alleviate this problem in Turkey and Iran bear some resemblance. In both countries, nonschool counseling graduates have been endorsed as school counselors to eliminate shortages and have created undergraduate programs to fill the gap in a shorter time period. It appears that a discrepancy between the recommended student-to-school-counselor ratio and the current ratio in Egypt will worsen due to a rapid increase in the population. Further research is needed regarding possible reasons for the shortage, and a nationally representative needs assessment is required to make future projections. Based on the evidence of current research, both policy-level decision-makers and counselor education institutions should commit to create a unified solution to the shortage.

Unfortunately, the Middle East is a conflict-prone region . Often, school-aged children are affected by war, internal violence, terrorist attacks, and political instability. Due to this fact, Middle Eastern school counselors should be trained to respond to trauma, because school counseling cannot be considered in isolation from larger societal events. Therefore, they have to be equipped with the knowledge and skills necessary for school-based emergency crisis interventions in the event of mass tragedies, psychological first aid, and the necessary skills to aid in the grieving/healing process. It appears that the Israeli school counseling literature is relativity more well developed in terms of this need and might prove useful for other Middle Eastern school counseling professionals. In addition, school counselors can also play a “change agent” role with regard to social conflict. For example, peace education and multicultural education can be easily integrated into school counseling activities. However, in order to translate such ideas into practice, policy-level regulations are needed.

References

Abel, R. M., & Friedman, H. A. (2009). Israeli school and community response to war trauma a review of selected literature. School Psychology International, 30(3), 265–228.

Aladağ, M. (2013). Counseling skills pre-practicum training at guidance and counseling undergraduate programs: A qualitative investigation. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 13(1), 72–79.

Alavi, M., Boujarian, N., & Ninggal, M. T. (2012). The challenges of high school counselors in work place. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 4786–4792.

Akkoyun, F. (1995). Psikolojik danışma ve rehberlikte ünvan ve program sorunu: Bir inceleme ve öneriler [The title and curriculum problems in counseling programs: An investigation and recommendations]. Psikolojik Danışma ve Rehberlik Dergisi, 2(6), 1–21.

Amer, M. M. (2013). Counseling and psychotherapy in Egypt: Ambiguous identity of a regional leader. In R. Moodley, U. P. Gielen, & R. Wu (Eds.), Handbook of counseling and psychotherapy in an international context (pp. 19–29). New York: Routledge.

Aydın, İ., Arastaman, G., & Akar, F. (2011). Türkiye’de ilköğretim okulu yöneticileri ile rehber öğretmenler arasındaki çatışma kaynakları [Sources of conflict between primary school principals and school counsellors in Turkey]. Education and Science, 36(160), 199–212.

Bayrakcı, M. (2009). In-Service teacher training in Japan and Turkey: A comparative analysis of institutions and practices. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 34(1), 10–22.

Bektaş, Y. (2006). Kültüre duyarlı psikolojik danışma yeterlikleri ve psikolojik danışman eğitimindeki yeri [Multicultural counseling competences and the place of multicultural competences in counseling education]. Ege Eğitim Dergisi, 7(1), 43–59.

Birashk, B. (2013). Counseling and psychotherapy in Iran. In R. Moodley, U. P. Gielen, & R. Wu (Eds.), Handbook of counseling and psychotherapy in an international context (pp. 361–370). New York: Routledge.

Darcy, J., Francesca, S. D., Duncalf, B. J., Basbug, B., Buker, H. (2015). Turkey: Evaluation of UNICEF’s response to the Syrian refugee crisis in Turkey. Retrieved from: https://www.unicef.org/evaldatabase/index_86620.html.

Demirel, M. T. (2010). İlköğretim ve ortaöğretim kurumları sınıf rehberlik programının değerlendirilmesi [An evaluation of elementary and secondary schools’ class guidance curriculum]. Eğitim ve Bilim, 35(156), 45.

Doğan, S. (1998). Counseling in Turkey: Current status and future challenges. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 6, 1–12.

Doğan, S. (2000). The historical development of counseling in Turkey. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 22, 57–67.

Education Reform Initiative (ERI). (2015). Education Monitoring Report 2014-15 Executive Summary. Retrieved from http://erg.sabanciuniv.edu/en/our-publications

Ergüner-Tekinalp, B., Leuwerke, W., & Terzi, Ş. (2009). Emergence of national school counseling models: Views from the United States and Turkey. Journal of School Counseling, 7(33), 56. Retrieved from: http://www.jsc.montana.edu/articles/v7n33.pdf.

Erhard, R., & Harel, Y. (2005). Role behavior profiles of Israeli school counselors. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 27(1), 87–100.

Erhard, R., & Erhard-Weiss, D. (2007). The emergence of counseling in traditional cultures: Ultra-orthodox Jewish and Arab communities in Israel. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 29(3–4), 149–158. doi:10.1007/s10447-007-9035-8.

Erhard, R. L., & Sinai, M. (2012). The school counselor in Israel: An agent of social justice? International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 34(2), 159–173.

Fatemi, A., Khodayari, L., & Stewart, A. (2015). Counseling in Iran: History, current status, and future trends. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93(1), 105–113.

Gültekin, F. (2004). Bir savunucu olarak okul psikolojik danışmanı [School Counselor as an Advocator]. Eğitim Araştırmaları, 15, 56–65.

Harris, B. (2013). International school-based counselling scoping report. Counselling Minded. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259077683_School-based_counselling_internationally_a_scoping_review

Higher Education Council (HEC), (nd). Guidance and psychological counseling program. Retrieved from https://www.yok.gov.tr/documents/10279/49665/rehberlik_psikolojik.pdf/417fa2f0-1361-44ae-b06a-2b866f27156c

Higher Education Council (HEC), (1997). Eğitim fakültelerinde uygulanacak yeni programlar hakkında açıklama [Announcement of new programs for faculties of education]. Retrieved from www.yok.gov.tr/egitim/ogretmen/aciklama.doc

Horenczyk, G., & Tatar, M. (2004). Education in a plural society or multicultural education? The views of Israeli Arab and Jewish school counselors. Journal of Peace Education, 1(2), 191–204.

Israelashvili, M. (2013). Counseling in Israel. In T. H. Hohenshil, N. E. Amundson, & S. G. Niles (Eds.), Counseling around the world: An international handbook (pp. 283–291). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Israelashvili, M., & Wegman-Rozi, O. (2012). Formal and applied counseling in Israel. Journal of Counseling & Development, 90(2), 227–232. doi:10.1111/j.1556-6676.2012.00028.x.

Istanbul Bilgi University Children Study Unit (ÇOÇA). (2015). Suriyeli mülteci çocukların Türkiye devlet okullarındaki durumu. [The situation of Syrian refugee children in Turkish public schools]. Retrieved from Retrieved from: http://cocuk.bilgi.edu.tr/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Suriyeli-Cocuklar-Egitim-Sistemi-Politika-Notu.pdf.

Jimerson, S. R., Alghorani, M. A., Darweish, A. H., & Abdelaziz, M. (2010). School psychology in Egypt results of the 2008 International School Psychology Survey. School Psychology International, 31(3), 219–228.

Kağnıcı, M. (2011). Çok kültürlü psikolojik danışma eğitiminin rehberlik ve psikolojik danışmanlık lisans programlarına yerleştirilmesi [Accommodating multicultural counseling training in the guidance and counseling undergraduate programs]. Türk Psikolojik Danışma ve Rehberlik Dergisi, 4(40), 222–231.

Karayanni, M. (1996). The emergence of school counseling and guidance in Israel. Journal of Counseling & Development, 74(6), 582–587.

Keklik, İ. T. (2010). Psikolojik danışma alanının hak savunuculuğu bağlamında birey ötesi sorumlulukları [Advocacy: responsibilities of the field of counseling beyond the individual client]. Türk Psikolojik Danışma ve Rehberlik Dergisi, 4(33), 89.

Klingman, A. (2002). From supportive-listening to a solution focused intervention for counselors dealing with political trauma. British Journal of Guidance & Counseling, 30(3), 247–259.

Korkut, F. (2007). Counselor education, program accreditation and counselor credentialing in Turkey. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 29(1), 11–20.

Korkut-Owen, F., Damırchı, E. S., & Molaei, B. (2013). İki Orta Doğu ülkesinde psikolojik danışma ve rehberlik: Türkiye ve İran [Counseling in two Middle East country: Turkey and Iran]. Uludağ Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 26(1), 81–103.

Korkut, F., & Mızıkacı, F. (2008). Avrupa Birliği, Bologna süreci ve Türkiye’de psikolojik danışman eğitimi [European Union, Bologna process and counselor education in Turkey]. Kuram ve Uygulamada Eğitim Yönetimi Dergisi, 53, 99–122.

Korkut-Owen, F., & Owen, D. W. (2008). Okul psikolojik danışmanlarının rol ve işlevleri: Yöneticiler ve psikolojik danışmanların görüşleri. [School counselor’s role and functions: school administrators’ and counselors’ opinions]. Ankara Üniversitesi Eğitim Bilimleri Fakültesi Dergisi, 41(1), 207–221.

Korkut-Owen, F., Owen, D. W., & Ballestero, V. (2009). Counselors and Administrators: The collaborative alliance in three countries. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research (EJER), 36, 23–38.

Korkut-Owen, F., & Güneri, O. Y. (2013). Counseling in Turkey. In T. H. Hohenshil, N. E. Amundson, & S. G. Niles (Eds.), Counseling around the world: An international handbook (pp. 293–302). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Köse, A. (2015). Okul psikolojik danışmasında liderlik araştırmaları için yeni bir analitik çerçeve: dağıtımcı liderlik [A new analytical framework for leadership studies in school counseling: Distributed leadership]. Türk Psikolojik Danışma ve Rehberlik Dergisi, 5(43), 137.

Köse Şirin, A., & Diker Coşkun, Y. (2015). Okul psikolojik danışmanlarının sürekli eğitim ihtiyaçlarının incelenmesi [Analysis of school counselors’ continuing education needs]. International Journal of Curriculum and Instructional Studies, 5(9), 105–122.

Lazovsky, R., & Shimoni, A. (2007). The on-site mentor of counseling interns: Perceptions of ideal role and actual role performance. Journal of Counseling & Development, 85(3), 303–316.

Mikhemar, S. (2013). Counseling in Egypt. In T. H. Hohenshil, N. E. Amundson, & S. G. Niles (Eds.), Counseling around the world: An international handbook (pp. 275–283). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Ministry of National Education (MoNE). (2001). Rehberlik ve psikolojik danışma hizmetleri yönetmeliği [Regulations for counseling and guidance services]. Retrieved from http://mevzuat.meb.gov.tr/html/68.html

Ministry of National Education (MoNE). (2006). İlköğretim ve orta öğretim kurumları sınıf rehberlik Programı [Elementary and secondary schools classroom guidance program]. Retrieved from http://orgm.meb.gov.tr/alt_sayfalar/sinif_reh_progrm.html

Ministry of National Education (MoNE). (2011). Ortaöğretim rehberlik ve yönlendirme dersi programı [Secondary schools guidance and orientation lesson program]. Retrieved from http://orgm.meb.gov.tr/alt_sayfalar/form_standar/sinif_rehber_prog/O_R_Y_P_E_O.pdf

Ministry of National Education (MoNE). (2014). Rehberlik ve kariyer planlama dersi programı [Guidance and career planning lesson program]. Retrieved from http://ttkb.meb.gov.tr/dosyalar/programlar/ilkogretim/ortaokul_rehberlik_programi.pdf

Moussa, S., Kholy, M. E., Enaba, D., Salem, K., Ali, A., Nasreldin, M., et al. (2015). Impact of political violence on the mental health of school children in Egypt. Journal of Mental Health, 24(5), 289–293.

Nazlı, S. (2006). Comprehensive guidance and counselling programme practices in Turkey. Mediterranean Journal of Educational Studies, 11(1), 83–101.

Nazlı, S. (2007). Psikolojik danışmanların değişen rollerini algılayışları [School counselors’ perception of their changing roles]. Balıkesir Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, 10(18), 1–17.

Pişkin, M. (2006). Türkiye’de psikolojik danışma ve rehberlik hizmetlerinin dünü, bugünü ve yarını. Türkiye’de eğitim bilimleri: Bir bilonço denemesi. Ankara: Nobel Yayın Dağıtım.

Poyrazlı, Ş., Doğan, S., & Eskin, M. (2013). Counseling and psychotherapy in Turkey: Western theories and culturally inclusive methods. In R. Moodly, U. P. Gielen, & R. Wu (Eds.), Handbook of counseling and psychotherapy in an international context (pp. 404–414). New York: Routledge.

Rantissi, G. (2002). School counselling: The role of the school counsellor as expected and enacted as this is perceived by selected school counsellors and members of their role set in some Arab schools in Israel. Doctoral dissertation, Education.

Şeker, B. D., & Aslan, Z. (2015). Refugee children in the educational process: An social psychological assessment. Kuramsal Eğitimbilim Dergisi, 8(1), 86–105.

Şensoy-Briddick, H., & Briddick, C. (2015). A national comprehensive school counseling program: A rationale and theoretical analysis of its implication for Turkey. In F. Korkut-Owen, R. Özyürek, & D. W. Owen (Eds.), Gelişen psikolojik danışma ve rehberlik: Meslekleşme sürecinde ilerlemeler (pp. 95–111). Ankara: Nobel Yayıncılık.

Sezer, E. (2006). Milli Eğitim Bakanlığına bağlı devlet okullarında çalışan psikolojik danışman ve rehber öğretmenlerin hizmetiçi eğitime ilişkin görüşlerinin değerlendirilmesi (İstanbul ili örneği) [The evaluation of school counselors’ perception about in-service training (Case of Istanbul)]. Unpublished master’s thesis. Istanbul: Yeditepe University.

Shimoni, A., & Greenberger, L. (2014). School counselors deliver information about school counseling and their work: What professional message is conveyed? Professional School Counseling, 18(1), 15–27.

Siyez, D. M., Kaya, A., & Uz Bas, A. (2012). Investigating views of teachers on classroom guidance programs. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 48, 213–230.

Stockton, R., & Güneri, O. (2011). Counseling in Turkey: An evolving field. Journal of Counseling & Development, 1, 98–104.

Tatar, M. (2012). School counsellors working with immigrant pupils: Changes in their approaches after 10 years. British Journal Of Guidance & Counselling, 40(5), 577–592. doi:10.1080/03069885.2012.718738.

Tatar, M., & Horenczyk, G. (2003). Dilemmas and strategies in the counselling of Jewish and Arab Palestinian children in Israeli schools. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 31, 375–391.

Terzi, Ş., Ergüner-Tekinalp, B., & Leuwerke, W. (2011). Psikolojik danışmanların okul psikolojik danışma ve rehberlik hizmetleri modeline dayalı olarak geliştirilen kapsamlı psikolojik danışma ve rehberlik programını değerlendirmeleri [The evaluation of comprehensive guidance and counseling programs based on school counseling and guidance services model by school counselors]. Eğitim ve Öğretim Dergisi, 1(1), 51–60.

Turkish Statistical Institute (TUIK). (2014). Turkey in Statistics, 2014. Retrieved from www.turkstat.gov.tr/IcerikGetir.do?istab_id=5

Turkish Council of Higher Education Student Selection and Placement Center. (2015). Higher education programs and quato guideline. Retrieved from http://www.osym.gov.tr/belge/1-23560/2015-osys-yuksekogretim-programlari-ve-kontenjanlari-ki-.html

Turkish Psychological Counseling and Guidance Association (TPCGA). (2011). Guidance counselor data. Retrieved from http://pdr.org.tr/upload/icerik/haberler/sayilar1.pdf

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHRC). (2016). Syria regional refugee response. Retrieved from http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/country.php?id=224

Yeşilyaprak, B. (2009). The development of the field of psychological counseling and guidance in Turkey: Recent advances and future prospects. Ankara University, Journal of Faculty of Educational Sciences, 42(1), 193–213.

Yeşilyaprak, B. (2012). The paradigm shift of vocational guidance and career counseling and its implications for Turkey: An evaluation from past to future. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 12(1), 111–118.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Köse, A. (2017). School-Based Counseling, Policy, Policy Research, and Implications in Turkey and Other Middle Eastern Countries. In: Carey, J., Harris, B., Lee, S., Aluede, O. (eds) International Handbook for Policy Research on School-Based Counseling. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58179-8_25

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58179-8_25

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-58177-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-58179-8

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)