Abstract

School-based counselling is indispensable in the educational system of any nation. It is the arm of education that develops and sustains students’ academic, vocational and personal-social needs. For first-hand information on how school-based counselling has grown in Nigeria, it becomes imperative to examine the policies made about it and to what extent these policies have influenced counselling in Nigeria. The authors therefore succinctly investigated the history and policy, challenges, crisis and problems, summary and evaluation of research policy and impact of capacity building on school-based counselling. The authors also pointed out the future outlook of school-based counselling in Nigeria and concluded that policies on school-based counselling rarely exist in Nigeria. The dearth has obviously affected the training, retraining, practice and future direction of school-based counselling in Nigeria. They agreed that concerted efforts need to be made by stakeholders, which include government at all levels to ensure that existing policies on school-based counselling are strengthened and new ones are promulgated, that would positively affect school-based counselling practices in Nigeria.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Policymaking as a vital and an important phenomenon of all socio-political systems helps in articulating or shaping the different opinions and directions of governance. Invariably, right policies coupled with equal purposeful implementations would be necessary for the advancement of good governance. In this atmosphere, therefore, policy research becomes a necessary tool for advocacy towards shaping the opinions of government on issues and problems affecting the general public. In this direction, policy research institutionalises policy monitoring and evaluation in a given clime. In view of the fact that every society provides the context for the interplay of policy initiatives and outcome, Nigeria which is currently the most populous black nation in the world has got her own share of policies that affect and also define governance and the well-being of the populace. Based on the philosophy inherent in policy research, this chapter focuses on the policy, capacity building and school-based counselling in Nigeria and neighbouring countries. The structure of this chapter is as follows: Firstly, the historical and policy-related dimensions are presented. Secondly, we sketched known crisis and problems that affect education generally and counselling as well. Next in line are the summary and evaluation of important policy research and also the impact of capacity building on school-based counselling in Nigeria. Finally, the future outlook for school-based counselling in Nigeria completes the picture.

History and Policy on School-Based Counselling in Nigeria

Education as a vital component for the development of any nation would certainly involve effective and efficient planning and service delivery. Consequently, different governments and policymakers have sought to utilise education as a vehicle for capacity building and social reintegration within the society. Towards achieving these objectives, education in Nigeria has undergone a series of changes through different policies by different governments. Worthy of note is that the history and policy of school-based counselling is inherent in the history and policy of education in Nigeria. To have a clear understanding of the subject matter, a reference to the different policies on education, from the colonial era to the present day, would be necessary. Nigeria, officially known as the Federal Republic of Nigeria (FGN) , is a vast and diverse country, a federation of 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT ; Abuja). The federal and state governments placed a high premium on education as both regard education as a catalyst for development. Nigerian educational system took its root from the missionary education, which dates back to the colonial era in the 1840s. This missionary education was vehemently criticised by the Nigerian elites who saw it as watery, religiously oriented and non-productive. Consequently, the elites demanded for a better educational system that would make the citizens useful in all spheres of human endeavour. To sustain a better education, various education ordinances and codes (1882, 1887, 1916, 1926, 1946 and 1926) in form of policies were set up by the colonial masters. This brought great developmental strides in Nigerian educational system.

First among such ordinances was the 1882 Education Ordinance , which was enacted to check the excesses of the missionaries’ education and to promote and assist education in the Gold Coast Colony that comprises the present-day Nigeria and Ghana. The ordinance saw the constitution of a general board of education whose aim was to control the missions’ schools and also give financial support in form of grant-in-aids to schools (Fafunwa, 1995). This ordinance did not also meet the educational need of the African nationalists who saw the colonial masters as paying lip service to education. As a result, the 1887 ordinance was enacted to consolidate and amend the laws relating to the promotion of education in Lagos Colony. This was the first attempt by the colonial masters to promote education and control the teeming expansion of schools by the missions. The ordinance that had a new board of education was empowered to handle the issues of grants in the infant, primary, secondary and the industrial schools. For the first time, the colonial government accepted some responsibilities for secondary school education . For example:

-

1.

They provided grant-in-aids.

-

2.

Teachers were to be trained, examined and awarded certificates.

-

3.

Teachers were to receive stipulated salaries, thus teaching became a career (Oshokoya, 2002).

Also, in 1906, the protectorate of Southern Nigeria and the colony of Lagos were merged and that gave rise to another educational ordinance for the areas in 1908. The educational department was reorganised to enable it to cover all areas of education in the new protectorate. But these efforts made by the colonial government in the way of ordinances, establishment of schools, supervision and funding of education, among others, appeared to have made little or no impact on educational system in Nigeria and other West African countries. Based on this, Lord Lugard (the then governor of the protectorate) came up with another education ordinance and code in 1916 to improve education in the Nigerian protectorates. The ordinance had the following items: grant-in-aid to be offered, nature of school, discipline and moral instruction in schools. Lugard’s effort brought no respite to the nationalists who became very vocal in their criticism, and their agitations were put in print and in the audio media across the globe. These agitations birthed the Phelps-Stokes Commission , which was set up to upgrade the system. The commission gave rise to the 1926 Education Ordinance which was a landmark in the development of education in Nigeria. There was yet another education ordinance in 1942. Though it was short-lived, it considered a 100% salary grants for teachers without reference to the efficiency of schools. This ordinance was cancelled by the advisory committee. By 1948 another ordinance came up. The main provisions included the registration of all teachers, the procedure for opening a new school and closing a school and the right of inspectors in schools. This ordinance contributed to educational development in Nigeria. The 1952 Education Ordinance was enacted to promote education in the newly created Eastern, Western and Northern regions, and it became an education law for the country. Yet, in all these ordinances or policies, school-based counselling was never considered from 1840 to 1958. See Table 16.1 for the summary of the ordinances or policies.

In 1959 the minister of education then set up a commission on the post institution and higher education to examine Nigeria’s needs in the field of post school certificate and higher education over the next 20 years. While this process was going on, some Catholic reverend sisters at St. Theresa’s College, Oke-Ado, Ibadan, 1959, brought school-based counselling to limelight via vocational counselling . The history and policy of school-based counselling in Nigeria is traced to this group of Catholic sisters in St. Theresa’s College Oke-Ado, Ibadan, in 1959. They saw the need to educate their final-year students on vocational issues such as employment, world of work and the right attitude towards work. One outcome of this meeting was the distribution of 54 out of the 60 graduating students’ career information that enabled the students to gain employment after graduation (Ipaye, 1983 as cited in Aluede, 2000). The career information efforts included experts in different fields who had made their marks in various professions and gave talks to the graduating students. The success of the programme facilitated other schools in Ibadan and other towns around Ibadan to embark upon same career talks for their senior students and also establish of the Ibadan Career Council . As would be expected, career masters and mistresses sprang up. They were assigned the job of collation and disseminating career information to students. In spite of the tremendous effort of these reverend sisters, counselling did not grow beyond career planning.

Another important era in the policy formulation during the colonial period was the Ashby commission of 1960 , also known as investment in education. The Ashby commission made a big impression on Nigeria’s education system. The report of the commission led to a high level of consultation with top professional officers of the ministries of education, and it became the basis of educational development. The effects of the report were characterised by the expansion in the primary education, diversified secondary school curricula, fresh efforts in technical and agricultural education, variety of services and courses and considerable expansion in university education. Perhaps as fallout from Ashby commission, 16 Nigerian educators visited Sweden, France and the USA in 1962, partly to acquire information on career counselling. The Nigerian Career Council (NCC) also organised a workshop for career masters/mistresses and principals on vocational courses and for guidance teachers in 1967 (Makinde, 1983). By 1969 a conference on curriculum development was held in Lagos. The conference was planned to deal with the following: the objectives of education, the content of curriculum, the methods and the material equipment. The conference also covered primary, secondary, university, teacher education, education for women and science and technology in national development. Surprisingly, school-based counselling was not officially included in the conference. But, the activities of the Nigerian Career Council (NCC), which was spearheaded by the Counselling Association of Nigeria (CASSON) , publicised counselling in the country’s education sector, to the extent that an Inspector of Education was appointed for vocational and educational guidance in 1972 (Iwuama, 1991). The curriculum conference of 1969 gave rise to the philosophy of the Nigerian education.

After the Nigerian Civil War, attempt by the Federal Military Government (FMG) towards utilising a policy framework for the sustenance of education saw the launch of Universal Primary Education (UPE) in 1976. It was meant to be the foundation upon which other levels of education were to be built. The policy was predicated on the assumption that every Nigerian has a right to a minimum of 6 years education if he/she is to function effectively as a citizen of Nigeria that is free and democratic, just and egalitarian, united and self-reliant, with full opportunities for all citizens (Fafunwa, 1995). The policy had its objectives that included the following:

-

1.

Inculcation of permanent literacy and numeracy and the ability to communicate effectively

-

2.

The laying of sound basics of effective thinking

-

3.

Citizenship education as a basis of effective participation in and contribution to the life of the society

-

4.

Character and moral training and the development of sound attitudes

-

5.

Developing children’s ability to adapt to their changing environment

This policy paved way for massive enrolment of pupils into schools. The implementation of the policy solely concentrated on the cognitive development without a relative action on the affective development of school children. Counselling mechanism, which could have helped the affective development of children that were massively enrolled into school, was ignored. It would have been expected that the vehicle for achieving the fourth and fifth objective should be a well-funded school-based counselling. But school-based counselling got no explicit attention or mention in the policy document. Expectedly, the policy was heavily criticised for lack of proper planning which led to inadequate educational facilities/classrooms , insufficient trained teachers to cater for the massive number of students that came forward to benefit from the free education and total neglect of mental health mechanism of these individuals.

By 1977, the National Policy on Education (NPE) was introduced by the Federal Military Government led by retired General Obasanjo. The federal government saw the need to promote a functional technology-based type, not the British colonial type that could not uphold the economy. This policy introduced the 6-3-3-4 education policy. It stipulated 6 years of primary education, 3 years of junior secondary education, 3 years of senior secondary education and 4 years of university educations for the country. Cognisance of the fact that we live in the age of technology, the 6-3-3-4 education policy was envisaged to entrench scientific outlook and culture in the country. Towards entrenching this trend in science and technology education, government went as far as directing universities to enforce the policy of 60:40 ratios in admission for science to other disciplines (Ajeyalemi & Ejiogu, 1987). In addition it was felt that graduates did not seem to possess the required marketable skills to succeed in the labour world. Consequently, the 6-3-3-4 education policy failed to address the apparent imbalance or mismatch between education and employment realities (Ajeyalemi & Ejiogu, 1987). The NPE of 1977 was then revised in 1981 (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1981). It marked a great change from the British system of education which Nigeria inherited at independence in 1960 on education system that stipulated 6 years in the primary school, 5 years in the secondary and 4 years in the university (6-5-4) to the implementation of 6-3-3-4 American system of education, that is, 6 years of primary education, 3 years of junior secondary school, 3 years of senior secondary school and 4 years of university education. For the first time, guidance and counselling was included in the policy document of the National Policy on Education (1981). This inclusion of counselling in the National Policy on Education perhaps may be due to the activities of the career masters and mistresses in post-primary schools. Though the article for guidance and counselling in the National Policy on Education (NPE) was written in few lines in Paragraph 83 (II) of the policy document, at least the Federal Government of Nigeria recognised the importance of counselling. The article reads in part:

In view of the apparent ignorance of many young people about career prospects, and in view of personality maladjustment among school children, career officers and counsellors will be appointed in post-primary institution…. Guidance and Counseling will also feature in teacher education programmes. (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1981, p.30)

There is no doubt that the policy planners had a wrong orientation of what guidance and counselling is all about. Their narrow mindedness about the profession could be the main reason for the way school-based counselling was handled in the policy. For example, the policy statement should involve the three foci of counselling that are education, vocational and personal-social. It should, likewise, clearly define the aims of guidance and counselling as it affects the primary, secondary and tertiary institutions. Though the policy statement on counselling in the policy document seems to streamline counselling to career development, it also shows that the federal government agents on education are aware of the growing need of counselling among young people. By the year 2004, the policy was revised and it states:

In view of the apparent ignorance of many young people about career prospects, and in view of personality maladjustment among school children, career officers and counsellors shall continue to make provisions for the training of interested teachers in guidance and counselling. Guidance and Counselling shall also feature in teacher education programmes. Proprietors of schools shall provide guidance counsellors in adequate number in each primary and post-primary school. (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2004)

The statement above indicated that the federal government became aware of the importance of school counselling and the plight of young people in school. It therefore recommended that school-based counselling should be made available across the education levels, and also interested teachers should be trained in guidance and counselling. This led to the inclusion of counselling in teachers’ programme in most of the tertiary institutions in the country.

The 2011–2015 strategic plans for the development of education sector proposed by the Federal Ministry of Education were the direct result of the pressing need to revise the National Policy on Education (NPE). In the fifth edition (2008), six areas were marked to receive special attention during the period in questions. They were:

-

1.

Nigerian Education Management Information System (NEMIS)

-

2.

Teachers’ Development Needs Assessment (TDNA) System

-

3.

Monitoring Learning Achievement (MLA)

-

4.

Guidance and Counselling (G&C) system

-

5.

Quality Assurance (QA) system

-

6.

School-Based Management Committee (SBMC)

Obviously, the fourth item dwells on guidance and counselling, and to adduce reasons for including guidance and counselling , the drafters of the policy state inter alia:

Nigeria public schools generally lack co-ordinated and effective system of guidance and counselling of students. As a result of this, students pass through the system without the necessary guidance that might enhance their academic, personal and professional development. The result of this is the large number of school leavers going into higher education without the necessary preparation on how to approach future challenges. It is, therefore, necessary that steps are taken to urgently integrate guidance and counselling services into public education sector across levels. (P. 7)

These reasons seem more genuine and germane to warrant institutionalising guidance and counselling in schools. Hitherto, students went through the system without the necessary guidance that might enhance their academic, personal and professional development. This meant that large number of students who leave schools probably went into higher education without the necessary preparation on how to approach future challenges. Apart from helping school children to clarify issues that affect their cognitive, psychomotor and affective domain, counselling services also provide physical, social and psychological atmosphere and setting within which help can be given to school children. However, this latest policy is yet to be implemented for unexplained reasons.

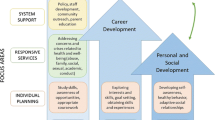

Meanwhile, the activities of Counselling Association of Nigeria (CASSON) have been a major boost to the development of school-based counselling in Nigeria. Their efforts have made it possible for the National Council on Education (NCE), the highest policymaking body on educational matters, to approve full-time practice for counsellors in post-primary institutions. Additionally, the National Universities Commission (NUC) in collaboration with the Federal Ministry of Education (FME) has set a minimum academic standard required for training counsellors. The association also developed a scheme that contains counselling needs of students from pre-primary, secondary and tertiary institutions. The purpose of the scheme is for counsellors to have a reference point for counselling and teaching at the various institutions (Table 16.2).

Challenges to School-Based Counselling in Nigeria

School-based counselling in Nigeria is faced with several challenges that include:

-

1.

Absence of professional identity: In Nigeria, school-based counselling like other counselling specialties is to assume professional status. So far, there is no legislation recognising counselling as a profession in Nigeria. As it stands today, anybody can lay claim and ascribe the title of counsellor to himself/herself.

-

2.

Lack of professional regulatory body: So far, there is no agency in Nigeria solely established and vested with authority to regulate the training, certification and practice of counsellor in Nigeria. So, you are likely to find a huge variation in the training patterns of counsellors from one university to another across Nigeria. Presently, only the National Universities Commission (NUC) accredits all programmes in Nigerian universities. This effort ought to be complemented by the counsellor regulatory body. Unfortunately, the act establishing the counselling of professional council of Nigeria is yet to be promulgated into law in Nigeria.

-

3.

Majority of the school in Nigeria do not have well-articulated guidance curriculum largely because of the absence of trained counsellors. Even in few schools that have counsellors, most of them are saddled with ancillary responsibilities. And in other cases, developmental guidance materials are scattered throughout the school time , thus making counselling lack accountability (Aluede, Adomeh & Akpaida, 2004; Aluede, McEachern & Kenny, 2005; Hui, 2000).

Crises and Problems in Nigeria

The crises in the education system in Nigeria are attributed to the long period of unplanned, uncoordinated policies of the system in Nigeria. It could be traced to the long period of undemocratic military regimes of military rule. In the 55 years of Nigeria’s independence from British colonial masters, the military ruled for 26 years and 4 years of unstable governance (interim regime), making a total of 30 undemocratic and unstable years. The situation nurtured and ushered the inconsistency and the crises in the education system in Nigeria today. A peculiar trait of the military during those years of their rule was the release of many educational policies in the form of decrees and edicts that were not implemented due to sudden and unstable change in the government leadership occasioned by coup d’états. Besides, the present crises in education have been attributed to the poor and unstable national leadership. This is characteristic of the different regimes in the past. Each new regime tends to commence new policies and projects with little or no attention given to the projects that the previous administration started. Consequently, a lot of unfinished and abandoned projects and facilities abound. Sequel to the above situation, the education system has become vulnerable to crises.

Besides this is the shortage of sufficient fund to finance education programmes at all levels in the country. This has partly led to the incessant strike actions by University lecturers under the aegis of Academic Staff Union of University (ASUU) and even secondary school teachers in some states of the federation. More so, there appear to be educational imbalances in Nigeria arising from the colonial elitist approach which was sustained after independence by Nigerian leaders. However, efforts have been made to redress the educational imbalances. According to Ityavyar (1985), in an attempt to change the structure of Nigerian education, the government established polytechnics and colleges of technology in each of the states of the federation. These changes were not sufficient to match the phenomenal growth in Nigeria.

Although many Nigerians have access to education now and literacy rate has increased, the problems of illiteracy still exist. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2010) asserts that about 10.5 million children between the ages of 8 and 15 years in Nigeria are out of school, so Nigeria is said to dominate 12 other countries Pakistan (5.1 million), Ethiopia (2.4 million) , India (2.3 million), Philippines (1.5 million), Cote d’Ivoire (1.2 million), Burkina Faso (1 million), Niger (1 million), Kenya (1 million), Yemen (0.9 million), Mali (0.8 million) and South Africa (0.7 million) as the country accounts for 47% of the global out-of-school population (Premium times, June 11, 2013). A bar chart of this is presented in Fig. 16.1.

This implies that one out of every five Nigerian children is out of school. So, the problem of inequalities of effective access to education has not been adequately addressed in some parts of the country.

Meanwhile, the criticisms that trailed different education policies point much more to the presence of crisis and problems in the system. Realistically, the educational policy landscape and outlook have always appeared undulating and uneven (Oramah, 2012; Nwabueze, 1995). It has been a bumpy ride for policy initiators and students alike. The crises stem largely from inadequate funding, diversion of funds or corruption and inattention or lopsided implementation of policies. In fact, policies are more likely to be terminated or replaced with another one by another government under the guise of providing a more comprehensive policy framework.

While government’s policy on Universal Primary Education (UPE) was receiving knocks and criticisms, another contentious decision came to light. Government takeover of schools through the Schools Takeover (validation) Decree No. 48 of 1977 has been very contentious in the country. People have remained divided on the merits and demerits of that decision/policy by the then military regime. The general outcry has been that the fallen standard of education in the country should be blamed on the forceful takeover of schools from the lack of seriousness by governments. Meanwhile, recent events in some states (notably Anambra, Delta and Imo states) in the country show that some state governments have returned or are beginning to return such schools to their original owners with the conviction that it will help raise the standards again. In other words, there is an apparent realisation now by some states in Nigeria that they are no longer fettered by policies that facilitated the takeover of schools in the past. This could be a possible recognition of the fact that diversity in education delivery is needed to maintain individuality and variety in character, opinions and modes of conduct among people (Nwabueze, 1995).

Research evidence points also to the overcentralisation policy frameworks as part of the root causes of education crisis and problems in the country (Adamolekum, 2013). Invariably, the federal governments through different policies have always usurped the roles of the states and local governments towards primary education as enshrined in the Nigerian constitution. In other words, in defiance to the provisions of the 1999 constitution that assign the sole responsibility for primary education to the states and local governments, the federal government through policies, like Universal Basic Education (UBE) , keeps the basic foundational education under its care and responsibility. Meanwhile, states and local governments are actually the governments that are very near to the people. Implementing education policies at the grassroots cannot be carried out very effectively by someone who is not at the grassroots level. This may have informed the opinion that the problem with education in Nigeria does not lie with policies but with their implementation by the successive governments (Nzeh, 2014).

There seems to be a regular desire to revise a policy that is in place by the government of the day without proper evaluation. In effect, education policies are not allowed to run their full course or lifespan as envisaged. For example, the Universal Primary Education of 1977 was revised in 1981. Then the Universal Basic Education came in 1999 and was revised in 2004. Since then, more revisions have been carried out. The present government through the then Minister of Education (Prof. Ruqqayatu Rufa’i) issued a 4-year education plan for the country in 2011. She has since been replaced as the Minister of Education. Therefore, she is no longer in position to oversee the implementation of a policy framework she brought out. Such policy may never be fully implemented. Lofty ideas and decisions are more likely to be abandoned by those who are not privy to them. They may be starved of funds either for political, religious or ethnic reasons. Starvation of funds could, however, come from economic reason. For example, allocation of funds to education reduced drastically in the 1980s and 1990s due to the sever decline in the oil market and the infamous Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) (Odukoya, 2014). It is obvious that an economy that is heavily dependent on a single commodity (oil) could have challenges when there is volatility in the international domain.

Summary and Evaluation of the Important Policy Research in Nigeria

It is apparent that educational policy research in Nigeria is still an emerging area. Such fact could be accountable for by the current trend whereby available literature understandably focused largely on the implementation and impact aspects of the policy frameworks in Nigeria. Therefore, researches have followed the path of critical analysis of governments’ actions and responsibilities towards uplifting the level of education in the country. Some of the analyses include the following.

Allocation and Policies on Nigeria’s Educational System

Nzeh (2014) while examining the impact of government’s budgetary allocation and policies on Nigeria’s educational system observed that the current level of development, technological capacity and capability is still very low and worrisome. This is not unexpected because Nigeria has not consistently met the UNESCO budgetary allocation benchmark of 26% to education. Consequently, he notes that a constant policy change is less an issue in comparison to the proper allocation and administration of funds or resource to the education sector.

Universal Basic Education (UBE) Policy

In a critical analysis of the Universal Basic Education (UBE) policy from the sociological perspective, Etuk, Ering and Ajake (2012) noted that despite its laudable objectives, the policy failed to take into consideration the current realities of Nigeria’s socio-economic and already existing educational conditions. Consequently, they reasoned that the implementation of the policy was bedevilled by problems of dearth of qualified teachers to handle the expanded number of pupils, lack of motivation and incentives for teachers, inadequate facilities and infrastructure and corruption. Removal of these hiccups would have made a lot of difference on the implementation of UBE policy in the country. Still on the impact of the government policy on education, Duze (2012) examined the effect of policy/programmes on the attrition or dropout rates in the primary schools. The author observes that the much-touted Education for All (EFA) by 2015 may suffer the same setbacks that inflicted the Universal Primary Education (UPE) which was conceived to uplift the foundation level of education and reduce drastically the incidence of dropout among school pupils.

Comparative Analysis on Counselling Policy

Meanwhile in a separate study, Ndum and Onukwugha (2012) gave a descriptive analysis on certain areas of congruence in the policy and practice of guidance and counselling between Nigeria and America. They observed that in both countries, vocational guidance was the bedrock of policies that were aimed at reducing problems related to unemployment. They, however, recognised the possible influence of American vocational movement on the advent of guidance and counselling in Nigeria in the 1950s as an identifiable aspect of Nigerian educational enterprise.

The Situation of Guidance and Counselling on the National Policy on Education

Durosaro and Adeoye (2010) in their analysis on the policy structure of guidance and counselling on the National Policy on Education (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2004) declared that though the federal government considers counselling as very important school service in the education sector, the policy programme was not properly implemented. This resulted from the fact that government failed to provide enough empowerment for the operators of the services of guidance and counselling in the school system. Thus, the gap caused by poor policy articulation, poor implementation as well as fallible administrative approach has been conceived as reasons for poor performance of guidance and counselling policy in the Nigerian education system. They also opined that the federal government’s establishment of the guidance and counselling programme in the National Policy on Education (1981, 2004) was a plausible idea. However, this effort still requires much of government’s honest commitment to facilitate the growth of the profession.

Omoni (2013) in her own observation summed up that though guidance and counselling as a profession has not been properly defined as it were, it should have been considered in the National Policy on Education as one of the educational services facilitating the implementation of educational policy, the attainment of policy goals and the promotion of effectiveness of the educational system. In the same vein, Arhedo, Adomeh and Aluede (2009) argue that this inadequacy of the sketchy representation of guidance counselling in the National Policy on Education could have been the reason for the profession not properly appreciated and accorded the recognition it deserves in the education industry.

Achebe and Nwoye (as cited by Alutu, 2007) assessing the essence of guidance and counselling in the National Policy on Education (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2004) believe that the non-inclusion of counselling services in the early child education by the federal government in Nigeria might be responsible for most misconduct of younger persons in the primary schools. Similarly, Alutu (2002) observes that though the National Policy on Education (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2004) explicitly stated the objectives of primary education, the problem of lack of implementation has worsened the challenges in the primary education.

Idowu (2013) in his research on guidance and counselling on the National Policy on Education observed that the skeletal statement made about guidance and counselling in the National Policy on Education (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2004) has relegated the profession to a mere process instead of the systematic process of assisting students with their personal, social, academic, emotional and career issues. He further stressed that educational process has three key factors that include the teachers, administrator/principal and the guidance counsellors. The teacher is preoccupied with instruction (cognitive and objective), the principal/administrator takes charge of the coordination which involves well-being of the entire school system whose components are persons, the physical plant, processes and products, while the guidance counsellors facilitate the affective and subjective curriculum. When all these three factors operate in unison, the contribution of education towards the realisation of the country’s educational objectives would have been realised.

The Federal Government Commitment to Guidance and Counselling

Alao (2009) posits that despite the priority, attention and financial commitment of the federal government to education sector, not so much have been achieved in meeting the goal and objective of education in Nigeria. Examining the new policy on National Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy (NEEDS) , the author stated that the delivery of education in Nigeria has suffered structural defect. The insufficient human resources especially in vocational and technical teachers to run the 6-3-3-4 system of education, coupled with the skeletal guidance and counselling services in the school system, have contributed immensely to the failure of the system. Alao (2009) further lamented the neglect of the vital benefits of counselling in meeting the goals and objectives of National Policy on Education. Accordingly, Alao (2009) argued that the essence of guidance and counselling in the furtherance of educational goals is being undermined in the National Policy on Education. The relevance of counselling by far outwits career counselling as stated in the National Policy on Education. Furthermore, it was noted that there are some other services of counselling which the federal government has not brought to glare. Areas such as the personal/social and academic counselling are imperative to the all-round development of the students (Alao, 2009).

It is, however, regrettable that proper policy on guidance and counselling has never been formulated; what is available is a policy on education where a terse statement is made on guidance counselling. With the frantic efforts of the Counselling Association of Nigeria (CASSON), it is hoped that a proper policy on guidance and counselling will be formulated and school-based counselling will take her rightful place in education sector in Nigeria.

Impact of Capacity Building on School-Based Counselling in Nigeria

The concept of capacity building is very vital to education in general and schools in particular. It is pertinent as it energises the quality of education and educational services. Capacity building is a strong tool for sustainable development in all facets of a nation’s life. It serves as the leverage that enhances the educational system. It includes the use of available technology to enhance learning and execute educational process. Capacity building involves how people use and apply their knowledge to uplift and develop their environment constructively. In recognition of the importance of capacity building, the United Nations declared the years 2005–2014 as the Decade for Education and Sustainable Development. In furtherance of this, Tambuwal (2009) asserts that we (stakeholders and educationists) should learn constantly about ourselves, our potentials, our limitations, our relationships, our society, our environment and our world. The essence of capacity building in education was partly mentioned by Tony Blair in his valedictory speech of his presidency of the European Union in 2006 as aptly cited by Tambuwal (2009) thus:

The new world we find ourselves inhibiting us, indifferent to tradition and past reputations, unforgiving of facility and ignorant of custom…. The task of modern government is to ensure that our countries can rise to these challenges… in science, education and lifelong learning to make… and to create a true knowledge….

Thus, in capacity building, information is very essential. Any individual who is not informed could act erroneously. Information is seen as the heartbeat of counselling, as counselling helps to update the people’s knowledge to improve. Hence, school-based counselling assists students to identify and know special aptitudes and abilities to make appropriate choice of careers. Nigerian government acknowledges the importance of school-based counselling; hence, it is included in the curriculum for teachers’ preparation programmes.

Counselling as an educational service is very vital to capacity building because it aims at assisting students to discover themselves, their worth and their capability. Sequel to this, the Federal Government of Nigeria recommended that every secondary school should have school-based counsellors in the school. The school-based counsellors would help the students to address various issues and resolve the concerns and problems of students in school. It is obvious that the rapid technological development and globalisation trend have led to radical changes in the world today. Besides, there is a great disparity between skills imparted by the educational system and the demand of the workplace. More so, disparity exists in educational sector in Nigeria between the participation of males and females and the Northern and Southern regions of the country. Disparity exists between the urban and rural schools and between institutions owned by the federal government and those controlled or owned by the state and private individuals. There exists an enormous lack of infrastructure/instructional materials for effective teaching and learning that appear to have negative effects in the quality of education at all levels.

Through school-based counselling, these different disparities would be addressed and the negative effects reduced if not completely removed. The obvious mismatch between the impart of education and the world of work could be traced to the inadequate and improper placement of students in the secondary schools. When counselling is accorded its rightful and proper place in the education system, the issue of identifying talents, training the students on the right skills and placing them appropriately would have been resolved. So, school-based counselling would help to guide students from the primary school level to the university level on the type of courses to pursue for a living based on their aptitude, attitude and interest. Similarly, those who are not able to catch up with the rigours and challenges of academic work, suitable placement would be made for them to assist and put them in the right career in line with their ability and attitude towards work and livelihood. Thus, counselling remains a vital part of the educational system. It enhances self-reliance and sense of industry and builds people’s capacity towards ultimately reducing economic frustration. The issue of human capacity building entails the production and empowering of individuals who have the competence to develop physical capacity for the nation. Denga (2009) asserts that counselling within education is potentially equipped to identify talents which can be developed to produce the necessary manpower to improve and develop the nation’s infrastructure.

The contributions of school-based counsellors in Nigeria are found in their involvement in various aspects of administration in the school system in areas such as psychological test administration and career guidance. Tests, such as aptitude/achievement and interest, are appropriate for the placement of students in education programmes which enhance capacity building and avoid waste. School-based counselling in Nigeria could develop appropriate programmes for the training of adolescent youths or students to address the country’s infrastructural needs for sustainable development.

The objective of education as enshrined in the National Policy on Education (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2013) is to achieve sustainable development of both human and materials. This can easily and reasonably be achieved through school counselling services in Nigeria. This according to Omohan and Maliki (2007) involves deliberate effort by a particular group of people (school counsellors) to help people cope better, understand more, and be more effective on any activity they are engaged in. All these are captured in the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 2000) declaration that says that the aims of counselling within the context of education is to “facilitate the smooth transition of children (students) from primary to secondary school, from secondary to post- secondary educational institutions and to the world of work”.

Ultimately, school-based counselling cannot be effective if the personnel or school counsellors are not retrained or exposed to the latest developments within their area of operation. Recognising this fact, Tambuwal (2009) opines that towards meeting the challenges of the educational reforms within the basic education level in Nigeria, there is need for capacity building and professional development of counsellors so that they become abreast with modern trends comparable with any standards in the world. This belief may have informed one of the stated objectives as contained in the 4-year strategic plan for the education sector 2011–2015 by the Federal Ministry of Education. It states the need to “recruit and/or retrain staff with particular attention in ensuring person and job specific recruitment”. This policy statement is an obvious improvement on the one that is contained in the National Policy on Education (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2004) which states that “since qualified personnel in this category is scarce, government will continue to make provision for training of interested teachers in guidance and counselling and counselling will continue to feature in teacher education programme”. This statement does suggest that government may have realised that school-based counselling is a specialised endeavour and not just one of the courses to be taught by “interested teachers” in a classroom. Perceiving counselling as a mere “course” and not a professional endeavour may have led to the seemingly palpable inattention on the part of the government to commit and specifically train and retrain willing personnel in school counselling.

Realistically, a non-provision of training that focuses on capacity building for school counsellors will continue to be the bane or the drawback for the full entrenchment of school-based counselling. Regrettably, various state governments and multinational corporate bodies in Nigeria are making scholarships available annually for science-based courses only. The same are not specifically made available towards training interested candidates in school-based counselling. By implication school counsellors that are currently working in some schools in the country actually trained and are retraining themselves without government intervention of any kind. Such prevailing atmosphere may have led to fewer school counsellors available to cater for the current large number of students in schools nationwide. Some schools have one or two school counsellors at most for a population of over 1000 students.

Future Outlook for School-Based Counselling in Nigeria

In line with the reality of globalisation , it must be said that the policy landscape in Nigeria is beginning to shape up despite a rather seemingly lopsided implementation. Based on the fact that Nigeria has pursued or maintained a positive response to the social demands of education through different policies (Nwagwu, 1997), some glimmer of hope could be seen on the horizon in Nigeria. Some emerging factors on the ground seem to give strong indication that the future is bright.

The first overriding strong factor that projects a positive outlook regarding education policies is that Nigeria desired to be governed and is currently being governed by acceptable, stable and democratically elected governments. Nigeria now has respite from military regimes over a number of years which translated to uninterrupted civilian rule in the region. Such atmosphere has enabled Nigeria to develop and implement both short-term and long-term policies without fear of being jettisoned or abandoned by unelected governments as experienced in the past. Stable government is sure to provide stable policy environment in a given clime. The content of a good policy may either be subverted or supported by the context or atmosphere of the implementation. Therefore, a stable democratic atmosphere could support a stable policy formulation and implementation. Expressing the same fact, Egonmwan (1991) believes that just as the content of a policy is an important factor in determining the outcome of implementation, so also is the context of policy implementation. The political landscape in Nigeria has remained stable, and it seems that education policies among others will surely no longer suffer lack of coordination and lack of continuity.

Another scenario that presents a rather positive future is that Nigerian government is currently placing strong emphasis on Information Communication Technology (ICT) and Vocational and Technical Education (VTE) . Most universities in Nigeria have partnered with their various governments towards producing skilled manpower in the areas of technology and information management. Corroborating this fact, Ifenkwe (2013) notes that a number of policies which actually emphasise scientific, technical and vocational education and more funding in research and development have been adopted as pathways for achieving technological and scientific transformation of Nigeria.

Concluding Remarks

Policies on school-based counselling rarely exist in Nigeria. This absence has obviously affected the training, retraining, practice and future direction of school-based counselling in Nigeria. It is hoped that concerted efforts would be made by stakeholders, including government at all levels in Nigeria to ensure that existing policies on school-based counselling are strengthened and new ones are promulgated, that would positively affect school-based counselling practices in Nigeria. Therefore, the following policy research questions related to school-based counselling are very critical for Nigeria at this time:

-

“What are the competencies that school-based counsellors must possess to be effective in schools?”

-

“What knowledge, attitudes and skills should be addressed in a national school counselling curriculum ?”

-

“What special direction should school-based counselling be focused on to be able to play a pivotal role in the emerging mental health agenda in Nigeria?”

-

“What programmes should be initiated by school-based counselling in Nigeria to effectively interface and key into the transnational school-based school counselling milieu?”

References

Adamolekum, L. (2013). Education sector in crisis: Evidence, causes, and possible remedies. A distinguish lecture delivered on 26th January 2013 at Joseph Ayo Babalola University, Ikeji Arakeji, Osun State, Nigeria.

Ajeyalemi, D., & Ejiogu, A. M. (1987). Issues, problems, and prospects in Nigerian education. In A. M. Ejiogu & D. Ajeyelami (Eds.), Emergent issues in Nigerian education (pp. 1–10). Lagos, Nigeria: Joja Educational Research and Publishers Ltd.

Alao, I. F. (2009). Counselling and Nigeria National Policy on Education: the question of relevance and competence. Retrieved from www.ajol.info

Aluede, O. (2000). The realities of guidance and counselling services in Nigerian secondary school: Issues and strategies. Guidance and Counselling., 15(2), 22–26.

Aluede, O. O., Afen-Akpaida, J. E., & Adomeh, I. O. C. (2004). Some thoughts about the future of guidance and counselling in Nigeria. Education, 125(2), 296–305.

Aluede, O. O., McEachern, A. G., & Kenny, M. C. (2005). Counseling in Nigeria and the United States: Contrasts and similarities. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 27(3), 371–380.

Alutu, A. N. G. (2002). Guidance and Counselling services in federal government colleges in Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Guidance and Counselling., 8(1), 162–181.

Alutu, A. N. G. (2007). Theory and practice of guidance and counselling. Ibadanria, Nigeria: Ibadan University press.

Arhedo, P. A., Adomeh, O. C., & Aluede, O. (2009). School counsellor’s roles in the implementation of Universal Basic Education (UBE) scheme in Nigeria. Edo Journal of Counselling, 2(1), 58–65.

Denga, D. I. (2009, August). Orientating Nigerians towards functional societal collaboration and partnerships for achieving the Goals of the seven points Agenda: Guidance and Counselling perspectives. Being a Maiden Distinguished Annual lecture of the Counselling Association of Nigeria (CASSON).

Durosaro, L. A. & Adeoye, E. A. (2010). National policy on education and administration of guidance and counselling in schools: Overview and the way forward. Retrieved from http//www.renedurosaro.com

Duze, C. O. (2012). Educational policies/programmes effect on attrition rates in primary schools in Nigeria. International Journal of Education administration and policy studies, 4(2), 38–44.

Egonmwan, J. A. (1991). Public policy analysis: Concepts and applications. Benin City, Nigeria: Resyin Publishers.

Etuk, G. R., Ering, S. O., & Ajake, U. E. (2012). Nigeria’s Universal Basic Education (UBE) policy: A sociological analysis. American International Journal of Contemporary Research, 2(7), 179–183.

Fafunwa, A. B. (1995). History of education in Nigeria. Ibadan, Nigeria: NPS Educational Publishers.

Federal Republic of Nigeria. (1981). National policy on education. Lagos, Nigeria: Nigerian Educational Council Press.

Federal Republic of Nigeria. (2004). National policy on education (Revised edition). Lagos, Nigeria: Nigerian Educational Council Press.

Federal Republic of Nigeria (2013). National policy on education (Revised). Abuja, Nigeria: FGN Publications.

Hui, E. K. P. (2000). Guidance as a whole school in Hong Kong: From remediation to student development. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 22, 69–82.

Idowu, I. A. (2013). Guidance and counselling in National Policy on Education. Retrieved from http/www.unilorin.edu

Ifenkwe, G. E. (2013). Educational development in Nigeria: Challenges and prospects in the 21st century. Universal Journal of Education and General Studies, 2(1), 7–14.

Iwuama, B. C. (1991). Foundations of guidance and counselling. Benin City, Nigeria: Supreme Ideal Publishers.

Makinde, O. (1983). Fundamentals of guidance and counselling. London: Macmillan publishers.

Ndum, V. E., & Onukwugha, C. G. (2012). Overview of policy and practice of guidance and counselling in Nigeria and United States of America (USA): The role of computer technology. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention, 2(4), 42–50.

Nwabueze, B. O. (1995). Crises and problems in education in Nigeria. Lagos, Nigeria: Spectrum Books Ltd.

Nwagwu, C. C. (1997). The environment of crisis in the Nigeria education system. Comparative Education, 33(1), 87–95.

Nzeh, E. (2014). Impact of government’s budgetary allocations and policies on Nigeria’s educational system. Retrieved 8th September 2014 from www.impactng.com/impact/news_one.php?article=63

Odukoya, D. (2014). Formulation and implementation of educational policies in Nigeria. Retrieved 8th September 2014 from http://www.slidshare.net/ernwaca/formualtion-and-implementation-fo-educational-policy-in-nigeria

Omohan, M. E., & Maliki, A. E. (2007). Counseling and population control in Nigeria. Journal of Human Ecology, 22(2), 101–105.

Omoni, G. E. (2013). Counselling and nation building in Nigeria: The past, current status, challenges and the future. African Journal of Education and Technology, 3(1), 28–36.

Oramah, E. U. (2012). Entrenching quality resource management within the university system: Utilising a counselling framework. In R. O. Olubor, S. O. Okotete, & F. Adeyanju (Eds.), Resources management in education and national development (pp. 317–329). Benin City, Nigeria: Institute of Education, University of Benin.

Oshokoya, I. O. (2002). History and policy of Nigerian education in world perspective. Ibadan, Nigeria: AMD Publishers.

Tambawal, M. U. (2009). Guidance and counselling and the challenges of educational reforms in Nigeria. Paper presented at the National Conference of Shehu Shagari College of Education, Sokoto, Nigeria.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Aluede, O., Iyamu, F., Adubale, A., Oramah, E.U. (2017). Policy, Capacity Building and School-Based Counselling in Nigeria. In: Carey, J., Harris, B., Lee, S., Aluede, O. (eds) International Handbook for Policy Research on School-Based Counseling. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58179-8_16

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58179-8_16

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-58177-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-58179-8

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)