Abstract

This paper compares the linguistic realisation of contrastive discourse relations in single-authored and co-constructed texts produced in an experimental setting in which participants were asked to produce a well-formed argumentative text based on a skeleton text reduced to minimal propositional information while still containing the original argumentative sequential organisation and default configuration of events. The goal was to understand the role of context – linguistic context (or: co-text) and social context - in discourse production, in discourse processing and in the construal of discourse coherence. The study is methodologically compositional across functional approaches to discourse grammar, discourse representation, and discourse pragmatics. The results of the experiment show that co-constructed and single-authored texts utilise a pool of contrastive discourse connectives with the single-authored texts additionally referring to and entextualising linguistic and social context, embedding contrastive contributions accordingly.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Contrastive discourse relation

- Discourse connective

- Coherence strand

- Discourse coherence

- Linguistic context

- Social context

- Contextualisation

- Entextualisation

1 Introduction

Natural-language communication is a context-dependent endeavour in which language users refer to themselves and their minds, and to each other and each other’s minds (Givón 2005), to the immediate and less immediate physical surroundings, including temporal and spatial settings, and to prior and potentially succeeding talk, all of them being constitutive parts of cognitive, social and linguistic context (Fetzer 2012). Discourse – like context – has become more and more indispensible to the analysis of meaning in natural-language communication, and like context, the concept itself is used in diverging frameworks referring to different theoretical constructs. Discourse has been used synonymously with text, i.e. a linguistic-surface and thus linguistic-context phenomenon denoting longer stretches of written and spoken language, it has been used to refer to a sociocognitive construct, i.e. discourse-as-process and discourse-as-product performed and negotiated in social context, and it has been used to refer to both a theoretical construct and to its instantiation in context, i.e. type and token. The claim that discourse contains context, and that context contains discourse is not trivial, but rather refers to the relational nature of the two: both are parts-whole configurations in which the whole is more than the sum of its constitutive parts. From a linguistics-based perspective, discourse contains linguistic context (or: co-text), it relies on cognitive context for its production, processing, grounding and construal of discourse coherence, and it contains social context, for instance references to participants and to their temporal, spatial and discursive embeddedness. While discourse is generally conceived of as delimited by communicative formats, e.g. discourse genre, activity type or text-type (cf. discussion in Fetzer 2013), context is generally seen as unbounded, but may be assigned the status of a bounded entity when entextualisedFootnote 1 in discourse (cf. Fetzer 2011). It needs to be pointed out, however, that the unbounded nature of context does not mean that context is without any structure. If that were the case, natural-language communication would not be rule-governed and could therefore not be felicitous. Rather, context is relational, and “structured context also occurs within a wider context - a metacontext if you will - and that this sequence of contexts is an open, and conceivably infinite, series” (Bateson 1972: 245).

This paper examines the linguistic realisation of the discourse relations Contrast and Corrective Elaboration in argumentative discourseFootnote 2. Contrastive discourse relations are constitutive parts of argumentative sequences in which the relationship between premises and conclusions is negotiated. The paper compares the linguistic context and social context of contrastive discourse relations as well as their linguistic realisation in newspaper editorials from the quality paper The Guardian with those in single-authored and co-constructed argumentative texts from editing tasks, considering also excerpts of recorded metadata with the dyad’s negotiation about the appropriate linguistic realisation of contrastive discourse relations in context. The single- and co-constructed texts were produced in an experimental setting in which participants were asked to produce a well-formed argumentative text based on a skeleton text reduced to minimal propositional information while still containing the original argumentative sequential organisation and default configuration of events. Contrastive discourse relations are not only of interest because of their linguistic marking with contrastive discourse connectives, e.g. but, while or whereas, which are functionally equivalent to argumentative operators in the data at hand, with metacommunicative comments, such as surprisingly, and with pragmatic word order, that is temporal, spatial and other information positioned at the beginning of a clause (cf. Doherty 2003; Fetzer 2008), but also to internal and external, social-context-anchored negotiation-of-meaning sequences and the administration of discourse common ground (Fetzer 2007). The negotiation of communicative meaning goes hand in hand with the negotiation of the appropriateness of the linguistic realisation of speakers’ communicative intentions, considering the participants’ information- and face-wants (Brown and Levinson 1987) as well as the social- and linguistic-context constraints of discourse genre.

The paper is based on the premise that discourse is communicative action and thus anchored to rationality, intentionality and consciousness as well as to cooperation and contextualisation. Analogously to the status of relevance in relevance theory, that is communicative action comes in the presumption of being – optimally – relevant, discourse comes in with the presumption of being – more or less – coherent. In natural-language communication the production of discourse as well as its processing is based on this premise, and the premise also holds for discourse-as-a-whole and for its constitutive parts. The parts-whole perspective on discourse does not only imply the truism that the whole is more than the sum of its parts, but also that discourse is both process and product. Being both process and product requires discourse units to be conceptualised relationally and – to employ ethnomethodological terminology – doubly contextual (Heritage 1984), reflecting Bateson’s premise that “communication is both context-creating and context-dependent” (1972: 245). By contextualising prior discourse units, the contextualised units pave the ground for the production, processing and grounding of upcoming discourse units, thus indicating how the discourse is intended to proceed, i.e. whether there is some change in the intended direction as is signalled by contrastive discourse connectives or pragmatic word order, for instance, or whether there is no intended change and the discourse is to proceed as originally planned, as is signalled by continuative discourse connectives, such as additionally or moreover. Another consequence of the premise that discourse comes in with the presumption of being coherent is that discourse processing goes hand in hand with the construal of discourse coherence. While discourse processing is local and bottom-up focussing on individual constitutive parts, the construal of discourse coherence is both bottom-up and top-down, relating individual units with the larger whole.

2 Contrast and Corrective Elaboration

Approaching discourse from a pragmatics-anchored perspective is based on the premise that discourse and its constitutive parts are relational, relating discourse and context, discourse and communicative action, communicative action and language users, and language users with the things they do with words in discourse in context, and the things they do with discourse in context. Only a relational frame of reference can capture the dynamics of discourse, i.e. the unfolding of discourse-as-whole and variation of linearised sequences and variation within linearised sequences, and thus the connectedness between parts and wholes, transcending clearly delimited frames of investigation. Discourse comes in with the presumption of being – more or less – coherent, and language users construe discourse coherence when producing and interpreting discourse. The processing and construal of discourse coherence utilises linguistic and extra-linguistic material, for instance presuppositions, discourse connectives, coherence strands and discourse relations.

Discourse relations have been defined as logical relations holding between two or more discourse units (Asher and Lascarides 2003). For contrastive discourse relations, the relations express semantic dissimilarity manifest in content, illocutionary force and metacommunicative meaning. Coordinating discourse relations keep the discourse on the same level, while subordinating relations introduce a lower level in the discourse hierarchy. This is also reflected in the semantics of coordinating Contrast, which is defined as expressing semantic dissimilarity; subordinating Corrective Elaboration is defined as semantic dissimilarity with the topic of the second discourse unit’s proposition specifying the topic of the first discourse unit’s proposition mereologically.

To apply the theoretical construct of discourse relations to natural-language communication, logical relations have been operationalised within a pool of defining conditions which are encoded in coherence strands (cf. Givón 1993) and signalled with metacommunicative meaning. Coherence strands are:

-

topic continuity and referential continuity

-

temporal and aspectual coherence, including modality

-

lexical coherence

Metacommunicative meaning is signalled with:

-

discourse connectives

-

metacommunicative comments

-

pragmatic word order

The defining conditions of discourse relations are systematised in Table 1, which is adapted from Maier et al. (2016: 66–67):

Discourse relations are relational devices par excellence, relating the constitutive parts of discourse. In English, contrastive discourse relations are generally not only encoded in coherence strands but additionally signalled with discourse connectives, metacommunicative comments and pragmatic word order. Frequently they are also supplemented with additionally entextualised temporal, local, social and discursive context, intensifying the degree of discursive glueyness and thereby ensuring speaker-intended interpretation and speaker-intended construal of discourse coherence.

2.1 Data and Method

The linguistic realisation of discourse relations has been examined in written argumentative discourse, that is editorials from the British newspaper The Guardian, and in single-authored and co-constructed argumentative texts from an experimental setting. In the professionally produced public media texts Contrast and Corrective Elaboration were signalled with contrastive discourse connectives, primarily but, and pragmatic word order, but not generally furnished with further entextualised contextual information (Fetzer and Speyer 2012). To corroborate the results obtained and to shed more light on the assumption that discourse genre is a kind of blueprint in accordance with which language users produce and interpret texts, a case study has been undertaken to find out whether the results for the coding and signalling of discourse relations in an experimental setting based on an editing task, in which participants were asked to produce a well-formed argumentative texts based on a skeleton text with minimal propositional information, were similar to the ones obtained for professional argumentative media discourse. To test this, a study was set up to examine language users’ choices of signalling and encoding discourse relations when integrating a given sequence of discourse units with each other. The main interest was not whether or even how a relation between two given discourse units was realised, but rather the variation between different realisations of identical discourse-relation potential. In the study, participants were provided with a text that approximated an underlying representation, and they were asked to “flesh it out” into a fully operational text. Whenever it seemed possible to signal more than one discourse relation connecting two discourse units, participants needed to choose both the discourse relation to employ and whether to encode it in coherence strands only, or whether to encode it in coherence strands and signal it with discourse connectives and/or metacommunicative comments, and/or pragmatic word order (cf. Maier et al. 2016). Participants were provided with the ‘bare’ text, together with information about medium and genre of the original text (cf. appendix). Their task was to use and edit the ‘bare’ text and create a coherent and well-formed text of identical discourse genre, with the single constraint that the original sequence of discourse units had to remain unchanged. The data under investigation comprise two sets: 9 single-authored texts and 9 dyadically co-constructed texts, the latter supplemented with recorded metadata – a kind of think-aloud protocol, which documents the dyad’s negotiation about well-formed linguistic realisation. As an editing task with ‘minimal available text’ no new content needed to be generated, while it was still necessary to supplement and integrate additional linguistic material to arrive at an operational text and thus a well-formed, coherent whole. Intrinsic guiding criteria for the selection of additional material were (1) discourse genre as a blueprint, and (2) the sociocognitive construct of discourse common ground with intended readers of the resulting text.

All texts were segmented into discourse units, coded – and inter-rated – for discourse relations and analysed with respect to their linguistic realisations of discourse relations. Discourse relations are encoded in coherence strands and can additionally be signalled with discourse connectives, metacommunicative comments and pragmatic word order. While signalling ensures the activation of relevant defining conditions and thus guides the hearer in their interpretation of discourse relations as intended by the speaker, encoding defining conditions only in coherence strands may carry the risk of the discourse relation not being interpreted as intended by the speaker because the hearer may infer a different discourse relation.

2.2 Results

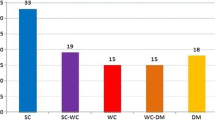

In the single-authored and co-constructed data, contrastive discourse relations are both encoded and signalled, which corroborates the results obtained from previous research. For the coordinating discourse relation of Contrast, but was the most frequently used discourse connective for both single-authored and co-constructed texts with the single-authored texts showing more variation in signalling Contrast, using also the contrastive marker while, which may signal both causal and temporal contrast. The subordinating discourse relation of Corrective Elaboration was signalled with various contrastive discourse connectives, showing a preference for however in the co-constructed texts and displaying more variation in the single-authored texts using the connectives yet, despite, instead of, though, although, however, and not just, and the metacommunicative comments even better and surprisingly. In coordinating Contrast as well as in subordinating Contrastive Elaboration, semantic dissimilarity was encoded in coherence strands, indexing referential and/or topic continuity, a shift in temporal and aspectual coherence (e.g., ‘nowadays’ – ‘in the past/in the post-war era’; ‘London of former days was’ – ‘London of today is much more’; ‘there was a time when NP was’ – ‘today this NP has changed’; ‘last time NP came here’ – ‘now it’s much more exciting!’), and lexical coherence, in particular in scalar or complementary antonymic lexical relations. Frequently the degree of ‘contrastiveness’ of the linguistic context was intensified by further linguistic material signalling temporal contrast (‘but now/today’; ‘however now/these days’). Sometimes further fully occupied discourse units were added in the single-authored texts, furnishing Contrast with Background or Explanation thereby not only intensifying the degree of discursive glueyness but also providing subjectified accounts for semantic dissimilarity or contrasting mereological topic specification with the function of accounting for the halt in the flow of discourse and supporting the administration of discourse common ground.

3 Discussion

Discourse relations have been defined by their defining conditions, which are encoded in coherence strands and which can additionally be signalled with discourse connectives, metacommunicative comments and pragmatic word order. The degree of specification of discourse relations in discourse is seen as a structure-based phenomenon depending on the number of coherence strands encoded and signals employed. Underspecification is defined as not fully encoding the defining conditions, thus allowing for multiple assignment of discourse relations, and overspecification is defined as fully encoding the defining conditions and adding discourse-relation-specific signals (discourse connectives, metacommunicative comment, pragmatic word order) to ensure speaker-intended interpretation.

In both single-authored and co-constructed texts, the defining conditions of contrastive discourse relations were encoded in coherence strands and signalled with contrastive discourse connectives, and/or metacommunicative comments, and/or pragmatic word order; sometimes more than one signal was used. The preferred contrastive discourse connective for Contrast was but, and the preferred initial constituent for pragmatic word order was a temporal adjunct (e.g., now, today). Frequently two signals were employed, intensifying the force of the contrastive discourse connective with pragmatic word order. For Corrective Elaboration, the preferred discourse connective was however.

3.1 Contrast

In the following, the encoding and signalling of the coordinating discourse relation of Contrast is analysed. The co-constructed examples are supplemented with extracts from their negotiation-of-production protocols. Examples (1) and (2) are from the co-constructed texts, and (3) and (4) from the single-authored texts. Temporal and aspectual coherence is printed in italics, topic and referential continuity is underlined, contrastive discourse connectives and metacommunicative comments are printed in bold, and lexical coherence is printed in small caps:

- (1):

-

#2/2 In the past, London was a dowdy place of tea-houses and stale rockcakes,

#2/3 but now it ’s much more exciting

- (2):

-

#1/7a While some Londoners might find these foreign tongues threatening,

#1/7b I delight in hearing them mingled with snatches of French, German, Spanish, Italian, Japanese …

In (1) and (2), the defining condition of Contrast, semantic dissimilarity between #2/2 and #2/3, and #1/7a and #1/7b, is encoded in topic discontinuity, which may, however, also count as mereological topic specification (‘some Londoners’ – ‘I’), temporal discontinuity (encoded in tense and adjunct), and lexical coherence encoded in antonymic lexical relations, sometimes intensified by comparative constructions (‘dowdy’ and ‘stale/much more exciting’; ‘past’ – ‘now’; ‘some’ – ‘I’; ‘threatening’ – ‘delight’), and it is signalled with the contrastive discourse connectives ‘but’ and ‘while’.

In the metadata, the signalling and encoding of semantic dissimilarity is also an object of talk, the dyads negotiating the kind of linguistic material which needs to be added to turn the bare text into a well-formed whole – with skeleton-text material printed in italics and the negotiation of linguistic material to be added printed in bold:

- B1::

-

{05:24} so here it says see also this is present | and then London was a dowdy place but now and now it’s much more exciting so we have put this in the right context so we could start with the british had seemed or in the past (2s)

- B1::

-

{06:31} erm (2s) erm (3s) i wrote i used now already see but now it’s much more exciting | but today how about today ’s much more exciting now how about if we do that but today

- A1::

-

mhm but today it’s

- B1::

-

much more exciting now walking

Participant B1 does not only mention the contrast to be encoded in tense and temporal adverbials, but also uses them (‘this is present’; ‘then’; ‘had seemed’; ‘in the past’; ‘but now’; ‘but today’) when s/he talks about the linguistic material to be filled in to transform the skeleton text into a well-formed argumentative whole. A very similar negotiation takes place between the second dyad, referring to tense (‘a jump from the present to the past’). B2 uses a contrastive discourse connective in their talk (‘while’), contextualising ‘rock cake’, which seems to have caused some processing problems, leading to partial understanding only, and also negotiating the degree of contrast to be added (‘it’s more exciting’ – ‘much more exciting’):

- B2::

-

{03:30} yeah there’s a jump from the present to the past right so there are hm hm case it’s true that london was a dowdy place but now it’s much more exciting or

- A2::

-

yeah

- B2::

-

while it is tr-

- A2::

-

in the past

- B2::

-

rock cake is erm like a scone but larger and hard | (2s) buttery

- A2::

-

uh huh {04:00} and stale rock cakes but now it’s more exciting?

- B2::

-

mhm much more exciting yeah

- A2::

-

yeah it’s much more exciting

In the single-authored examples (3) and (4), the defining condition of Contrast, semantic dissimilarity between #D/2 and #D/3, and #M/2 and #M/4 is encoded in topic and referential discontinuity (‘The landscape’ – ‘we’) in (3), and in topic discontinuity (‘London’ – ‘this negative perception’) and referential discontinuity (‘typical view’ – ‘recent survey’) in (4). It is also encoded in aspectual discontinuity (imperfective – perfective aspect) in (3), and temporal and aspectual discontinuity (‘was’ – ‘has changed’) in (4). Lexical coherence is encoded in antonymic lexical relations (‘look fairly similar – ‘changed dramatically’’; ‘be’ – ‘change’), and signalled with the contrastive discourse connective ‘but’ in (3) and with pragmatic word order with a fronted temporal adjunct in (4):

- (3):

-

#D/2 The landscape may look fairly similar

#D/3 but how we live, how we move around, how we work and who we live with has changed dramatically.

- (4):

-

#M/2 There was a time when the typical view of the overseas visitor was that London was a dowdy place of tea-houses and stale rock cakes.

#M/4 Today, according to a recent survey of tourists conducted by the London Bureau of Tourism, \( \underline{\textsc{this}}\,\underline{\text{negaive}}\,\underline{\textsc{perception}} \) has changed

The coordinating discourse relation of Contrast is – structurally speaking – overspecified in the co-constructed and in the single-authored texts, in spite of the fact that Contrast is the discourse relation with the lowest number of overlaps for defining conditions and therefore not very likely not be misinterpreted. There seems to be something special about Contrast, which may – like negation – count as a marked configuration (cf. Doherty 2003; Fetzer 1999; Horn 1989).

3.2 Corrective Elaboration

The defining conditions of the subordinating discourse relation of Corrective Elaboration are (1) sematic dissimilarity between two discourse units, and (2) the topic of the second discourse unit’s proposition specifies the topic of the first discourse unit’s proposition mereologically. In the co-constructed texts (examples (5) and (6)) and in the single-authored texts (examples (7) and (8)), all Corrective Elaborations are not only encoded in relevant coherence strands, but also signalled with a contrastive discourse connective, generally however:

- (5):

-

#2/8 Some would argue that London has become the capital of linguistic diversity.

#2/9 However, one important group seems to be leaving itself out:

- (6):

-

#3/8 Surprisingly, London has become the capital of linguistic diversity.

#3/9 However, one important group which seems to be excluding {skeleton text: ‘leaving’} itself {skeleton text: ‘out’}

Mereological topic specification is reflected in the parts-whole configuration of ‘London’ and ‘one important group’ in (5) and (6), which implies some kind of semantic dissimilarity; this is also made an object of talk in the dyad’s negotiation of well-formed realisation (‘it is a contrast because this is’ – ‘it’s a bit weird with like in fact and then however’). Semantic dissimilarity is also manifest in a shift in temporal and aspectual coherence (‘has become’ – ‘seems to be leaving itself out’). The degree of semantic dissimilarity is intensified in (5) with the metacommunicative comment ‘surprisingly’, signifying contrast of expectation, which has also been an object of talk in the negotiation of wellformedness:

- A2::

-

yeah but otherwise how would you link it?

- B2::

-

yeah

- A2::

-

i could just well I mean I’m just thinking |

- B2::

-

well I well ok i can you know or (5s) ok yeah &&& [stuttering] it is a contrast because this is ah|

- A2::

-

she can do this because she can do that|

- B2::

-

because she can yeah |

- A2::

-

(3s) i’m changing the text &&& [mumbling] however one

- B2::

-

&&& (mumbling) namely students

- A2::

-

(3s) it’s a bit weird with like in fact and then however

- B2::

-

yeah

- A2::

-

it’s like | a bit too much |

- B2::

-

mhm mhm well just leave it out in fact

- A2::

-

yeah (5 s) it’s like overdoing the transition | a bit|

- B1::

-

{08:01}ok and how about london has become the capital of linguistic diversity &&& surprisingly we need something in there | we need an adverb in there surprisingly or i don’t know

- A1::

-

yeah yeah let’s put in surprisingly

The single-authored data display very similar patterns but provide more social-context information, that is the source of the claim that London has become the capital of linguistic diversity is entextualised in ‘her husband’, and an additional discourse unit is added supplementing the Corrective Elaboration between #M/8 and #M/9 with the discourse relation of Background signalled with the discourse connective ‘while’ in (7). In (8) mereological topic specification is reflected in ‘an inquiry’ and its specification as ‘an inquiry into the impact of Tory educational policies’ signalled with pragmatic word order introduced by the metacommunicative comment ‘even better’. Semantic dissimilarity is also reflected in shifts in tense and modality (‘is under way’ – ‘would be better’):

- (7):

-

#M/8 Her husband interjected, “London has become the capital of linguistic diversity”.

#M/9 However [#10 while linguistic diversity might be a salient feature of the nation’s capital,] one important group seems to be leaving itself out:

- (8):

-

#S/13 An inquiry is underway—is not bureaucracy wonderful?

#S/14 Even better would be an inquiry into the impact of Tory educational policies on closing more and more students out from a university education.

The subordinating discourse relation of Corrective Elaboration is – like coordinating Contrast – overspecified in the co-constructed and single-authored texts, corroborating the results obtained for non-edited argumentative discourse. Structural overspecification thus seems to be the default for contrastive discourse relations in argumentative discourse. But why would language users opt for overspecification for contrastive discourse relations, which share only very few defining conditions with other discourse relations? We assume that the degree of overspecification has several reasons. Firstly, structural overspecification is an attention-guiding device and thus related closely to sociocognitive salience. Secondly, speakers/writers intend to secure the speaker-intended interpretation of contrastive discourse relations, which signal a change in the direction of discursive flow and therefore require particular attention, and thirdly, contrastive discourse relations have a decisive impact on discourse processing as they signal a change and potential restructuring in the administration of the current discourse common ground.

Discourse common ground is a dynamic construct, which is negotiated and updated continuously in natural-language communication, i.e. confirmed, modified or restructured, by storing new information and by updating already stored information. To account for discourse processing and for the construal of discourse coherence, discourse common ground is – analytically – distinguished into an individual’s representation of discourse common ground, that individual discourse common ground, and a collective’s representation of discourse common ground. Individual discourse common ground administers an individual’s administration of discourse processing and construal of discourse coherence, while collective discourse common ground administers negotiated and ratified individual discourse common grounds represented by collective discourse common ground; both may diverge to varying degrees (Fetzer 2007). Contrastive discourse relations may thus not only have a local impact on the administration of discourse common ground, but they may require some restructuring of already stored discursive information in the discourse common ground.

4 Conclusion

Discourse is a multilayered, complex construct, and so is its linearisation. The sequential organisation and linearisation of discourse is not only a linguistic-surface phenomenon, but rather depends on linguistic context, social context and cognitive-context-anchored discourse common ground, which is updated and administered continuously in discourse production and discourse processing. Contrastive discourse relations have an important function in discourse, signalling some change in the flow of discourse, and they have a particularly important function in argumentative discourse where they make manifest that one or more arguments may be controversial.

The structural overspecification of contrastive discourse relations found in the single-authored and co-constructed texts corroborates the results obtained for the linguistic realisation of contrastive discourse relations in media discourse. This provides strong evidence for assigning overspecification the status of default configuration for Contrast and Corrective Elaboration in argumentative discourse, where it is used strategically to contribute to the activation of defining conditions, foregrounding them, making them salient through overt marking and assigning communicative relevance to them. Underspecification, which has not been found for contrastive discourse relations, may reflect cognitive economy.

Context and discourse are dynamic relational constructs with context containing discourse and being contained in discourse. Consequently, context is presupposed in natural-language communication; it is imported into a discourse with indexical expressions or it is entextualised in discursive contributions or in some of its constitutive parts, and it is invoked in a discourse through inferencing. In argumentative discourse, overspecified contrastive discourse relations do not only signal negative contexts and trigger respective inferencing processes, but they also entextualise the kind of ‘negativity’.

A dynamic perspective on context entails contextualisation on the one hand, that is retrieving contextual information for discourse processing and discourse production, and grounding and anchoring discursive contributions in sociocognitive discourse common ground. On the other hand, it entails entextualisation, that is encoding and signalling of contextual information, for instance by narrowing down the referential domains of indexical expressions or by signalling contextual frames, as is the case with discourse connectives.

Discourse is interdependent on context, and context is interdependent on discourse. A pragmatic theory of discourse and its premise of indexicality of communicative action does not only offer insights into the multifaceted, multilayered and infinite theoretical construct of context and its instantiation in the production and processing of discourse, but also into the contextual constraints and requirements of discourse in general and of the delimiting frame of discourse genre in particular. By adopting both a bottom-up and top-down – or a micro and macro – approach to context and discourse, and by additionally accounting for interdependencies of their connectedness, it is possible to operationalize discourse with the delimiting frame of discourse genre, which is a structured whole with its genre-specific constraints and requirements. And it is also possible to delimit context as a delimiting frame of embedding context constrained by the contextual constraints and requirements of genre; the delimiting frame of embedding context may, of course, be expanded to a meta-level, should the communicative need arise. Context is thus not a set of propositions excluded from the content of a discursive contribution and construed against the background of the contribution. Rather, context is a constitutive – though not necessarily fully made explicit – part of the contribution. Thus, if context is not given and external to a discursive contribution but rather a constitutive part of it construed and negotiated in the production and processing of discourse, it has the status of an indexical; and if context has the status of an indexical, it can never be saturated. However, it is not only context, which is indexical, but also communicative action realised in the form of discursive contributions, which are carriers and containers of contextualised and entextualised objects as well as constitutive parts of it. Hence, it is not only indexical expressions contained in discursive contributions, which are contextualised in the production and processing of discourse, but rather the discursive contribution and discourse-as-a-whole.

Discourse studies have shown that there is systematic variation in the linguistic realisation of the contextual constraints and requirements of a discourse genre, both for the genre-as-a-whole and for its constitutive parts, as has been demonstrated for the encoding and signalling of contrastive discourse relations. Accounting for systematic variation with respect to the linguistic realisation of discourse and its constitutive parts – in particular with the explicit accommodation of context- and discourse-dependent sociocognitive discourse common ground – may not only lead to a re-assessment of language use, but also support context-dependent instantiations of document design. As for computer science and philosophy of language studies on context and communication, expanding the frame of reference from sentences and propositions to discursive contribution and discourse genre may lead to more refined insights.

Notes

- 1.

In discourse pragmatics, entextualisation refers to assigning unbounded context the status of a bounded object, for instance by narrowing down the referential domain of an indexical expression (here) to a bounded referential domain (here in Paris). The use promoted here differs from Park and Bucholtz (2009), who define entextualisation primarily in terms of institutional control and ideology. It shares their stance of approaching entextualisation in terms of “conditions inherent in the transposition of discourse from one context into another” (2009: 489), while considering not only global, but also local context.

- 2.

References

Anscombre, J.-C., Ducrot, O.: L’Argumentation dans la Langue. Mardaga, Brussels (1983)

Asher, N., Lascarides, A.: Logics of Conversation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2003)

Bateson, G.: Steps to an Ecology of Mind. Chandler Publishing Company, New York (1972)

Brown, P., Levinson, S.: Politeness. Some Universals in Language Usage. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1987)

Doherty, M.: Discourse relators and the beginnings of sentences in English and German. Lang. Contrast 3, 223–251 (2003)

Ducrot, O.: Le Dire et le Dit. Minuit, Paris (1984)

Fetzer, A.: Non-acceptances: re- or un-creating context? In: Bouquet, P., Benerecetti, M., Serafini, L., Brézillon, P., Castellani, F. (eds.) CONTEXT 1999. LNCS (LNAI), vol. 1688, pp. 133–144. Springer, Heidelberg (1999). doi:10.1007/3-540-48315-2_11

Fetzer, A.: Reformulation and common grounds. In: Fetzer, A., Fischer, K. (eds.) Lexical Markers of Common Grounds, pp. 157–179. Elsevier, London (2007)

Fetzer, A.: Theme zones in English media discourse. Forms and functions. J. Pragmat. 40(9), 1543–1568 (2008)

Fetzer, A.: ‘Here is the difference, here is the passion, here is the chance to be part of a great change’: strategic context importation in political discourse. In: Fetzer, A., Oishi, E. (eds.) Context and Contexts: Parts Meet Whole?, pp. 115–146. John Benjamins, Amsterdam (2011)

Fetzer, A.: Contexts in interaction: relating pragmatic wastebaskets. In: Finkbeiner, R., Meibauer, J., Schumacher, P. (eds.) What is a Context? Linguistic Approaches and Challenges, pp. 105–127. John Benjamins, Amsterdam (2012)

Fetzer, A.: Structuring of discourse. In: Sbisà, M., Meibauer, J., Turner, K. (eds.) Handbooks of Pragmatics. The Pragmatics of Speech Actions, pp. 685–711. de Gruyter, Berlin (2013)

Fetzer, A., Speyer, A.: Discourse relations in context: local and not-so-local constraints. Intercult. Pragmat. 9(4), 413–452 (2012)

Givón, T.: English Grammar. A Function-Based Introduction, vol. 2. Benjamins, Amsterdam (1993)

Givòn, T.: Context as Other Minds. John Benjamins, Amsterdam (2005)

Heritage, J.: Garfinkel and Ethnomethodology. Polity Press, Cambridge (1984)

Horn, L.: A Natural History of Negation. Chicago University Press, Chicago (1989)

Maier, R.M., Hofmockel, C., Fetzer, A.: The negotiation of discourse relations in context: co-constructing degrees of overtness. Intercult. Pragmat. 13(1), 71–105 (2016)

Park, J.S.-Y., Bucholtz, M.: Public transcripts: entextualization and linguistic representation in institutional contexts. Text & Talk 5, 485–502 (2009)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

Argumentative Skeleton Text and Instructions

The following 15 clauses form the backbone of a commentary from the Guardian. You may add or delete any linguistic material which you consider necessary to transform the current text into a well-formed coherent whole, but you may not change the order of the given clauses.

The solitary monoglots

-

1.

the British seem set on isolation from the world

-

2.

London was a dowdy place of tea-houses and stale rock cakes

-

3.

it’s much more exciting

-

4.

I can hear people speaking in all the languages of the world

-

5.

was that Pashto or Hindi

-

6.

I can just about differentiate Polish from Lithuanian

-

7.

I delight in hearing them mingled with snatches of French, German, Spanish, Italian, Japanese…

-

8.

London has become the capital of linguistic diversity

-

9.

one important group seems to be leaving itself out

-

10.

students

-

11.

foreign language learning at Britain’s schools has been in decline for decades

-

12.

the number of universities offering degrees in modern languages has plummeted

-

13.

an inquiry is under way

-

14.

the number of teenagers taking traditional modern foreign languages at A-level fell to its lowest level since the mid-90 s

-

15.

it’s a paradox

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Fetzer, A. (2017). Contextualising Contrastive Discourse Relations: Evidence from Single-Authored and Co-constructed Texts. In: Brézillon, P., Turner, R., Penco, C. (eds) Modeling and Using Context. CONTEXT 2017. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 10257. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57837-8_43

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57837-8_43

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-57836-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-57837-8

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)