Abstract

A 46-year-old man presented with a history of dyspnea and fatigue exacerbated by a recent hospitalization related to pulmonary edema. The diagnosis was confirmed by echocardiography, which revealed the presence of a bicuspid aortic valve with a mixed lesion, predominantly stenotic. The patient was submitted to aortic valve replacement with a stented bioprosthesis. The operation and his postoperative recovery were uneventful. He developed Staphylococcus epidermidis prosthetic valve endocarditis a month later, presenting in the emergency room with acute myocardial infarction. The mechanism of myocardial ischemia was a large aortic root abscess causing left main extrinsic compression. He was urgently taken to the operating room, and an aortic root replacement with cryopreserved homograft was performed, associated with autologous pericardium patch closure of aortic-to-right-atrium fistula and coronary artery bypass grafting of the left anterior descending. After a difficult postoperative period with multiple problems, he was eventually discharged home 6 weeks after surgery in good condition, with no signs of active infection. At 36-month follow-up, he is asymptomatic, currently in New York Heart Association functional class I, with no recurrent infection, ventricular function is normal, and the left main is widely patent, and the saphenous vein graft is occluded on control chest computed tomography.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Clinical Presentation

A 46-year-old man presented with a history of dyspnea and fatigue exacerbated by a recent hospitalization related to pulmonary edema. The diagnosis was confirmed by echocardiography, which revealed the presence of a bicuspid aortic valve with a mixed lesion, predominantly stenotic. The left ventricle had moderate systolic dysfunction and severe concentric hypertrophy. Past medical history was consistent with hypertension. Surgery was indicated for symptomatic severe aortic stenosis. A preoperative coronary angiogram did not reveal any abnormalities. The patient was submitted to aortic valve replacement with a stented bioprosthesis. The operation and his postoperative recovery were uneventful. He was prescribed the following medications to take at home: enalapril 5 mg twice daily, carvedilol 6.25 mg twice daily, furosemide 20 mg daily, and ferrous sulfate 300 mg daily (orally).

Approximately 1 month later, the patient returned, complaining of a high-grade fever and chills for a few days. He was admitted to the emergency department with acute-onset chest pain, dyspnea, and vomiting. On physical exam, he was lethargic, febrile, pale, and hemodynamically unstable, with cold extremities and faint pulses.

Diagnosis, Assessment, and Treatment

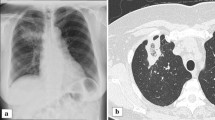

The admission electrocardiogram (ECG) is shown in Fig. 1. Laboratory values on admission demonstrated remarkable elevation of cardiac enzymes. The cardiologist on call interpreted the patient as having non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome and treated him with aspirin, clopidogrel, morphine, and heparin. An emergent coronary angiogram (Fig. 2) revealed a long, complex lesion on the left main coronary artery (80% lumen obstruction) with tapering contour, suggesting extrinsic compression. Due to ongoing myocardial ischemia and hemodynamic compromise, an intra-aortic balloon pump was inserted. The patient was further managed with intravenous fluids, inotropes, and mechanical ventilation. Blood cultures were drawn and identified as oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis. Before the blood cultures’ results were available, broad-spectrum antibiotics (vancomycin, rifampicin, and imipenem) and also an antifungal drug (amphotericin B) were initiated empirically. Renal function was impaired. Transesophageal echocardiography showed vegetations attached to the prosthesis, aortic root abscess, and an aortic-to-right-atrium fistula. Left ventricle ejection fraction was 36%, and there were wall motion abnormalities on lateral and anterior walls. Chest computed tomography (Fig. 3) suggested that left main compression was due to aortic root abscess or hematoma.

Urgent reoperative aortic valve replacement was indicated. Postoperatively, the patient had acute renal failure requiring hemodialysis, sepsis, transient liver failure, prolonged mechanical ventilation and complete atrioventricular block requiring permanent pacemaker. Antibiotic therapy, as previously mentioned, was initiated empirically with vancomycin, rifampicin, imipenem, and amphotericin B. Rifampicin was discontinued on the second day of use due to mild liver failure. Imipenem was used until the 14th postoperative day. Vancomycin was replaced by teicoplanin shortly after the operation due to acute renal failure, and it was used until the 30th postoperative day. Amphotericin B was used until the 34th postoperative day. Then, it was replaced by fluconazole, which was continued for a year thereafter.

A month after the operation, the left ventricular function had improved (ejection fraction of 58%) with a mildly dilated ventricle and a normal aortic valve function. The patient was discharged home 6 weeks after surgery in good condition, with no signs of active infection. At 36-month follow-up, the patient is currently in New York Heart Association functional class I with no recurrent infection, and the ventricular function is normal. The left main is widely patent and the saphenous vein graft is occluded on control chest computed tomography (Fig. 4).

Questions

1. Report the ECG in Fig. 1

Admitting electrocardiogram revealed normal sinus rhythm, signs of left ventricle hypertrophy, and ST depression on posterior and lateral leads.

2. What are the complications of prosthetic valve endocarditis?

Although infrequent (1–4% in the first year), infective endocarditis may occur after aortic valve replacement [8]. Prosthetic valve endocarditis is associated with elevated hospital mortality (approximately 40%) [4] and morbidity dependent on the infecting pathogen, duration of illness prior to therapy, and underlying comorbidities.

The main complications of endocarditis, by prevalence, are occurrences of cardiac complications (severe heart failure, valve injury, pericarditis, acute myocardial infarction, conduction abnormalities, fistulous communication, perivalvular abscess, and others), neurologic complications (cerebral embolism, mycotic aneurysms, meningitis, stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, cerebral abscess, and others), septic complications (infection unresponsive to treatment, persistent fever, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and others), renal complications (renal failure, nephrotic syndrome), extracranial systemic arterial complications, septic pulmonary embolisms, three splenic infarctions or abscesses, and some other complications associated with infective endocarditis [6].

3. What is the clinical presentation of acute coronary syndromes in patients with endocarditis?

Clinical presentation of acute coronary syndromes in patients with endocarditis is similar to those with coronary artery disease. As systems attempt to meet stringent door-to-balloon initiatives, it becomes imperative that a detailed history and physical exam be performed in this narrow time window in order to avoid unnecessary tests and/or therapeutic regimens.

4. What investigation is most likely to be diagnostic in this case?

The diagnostic workup of a patient with a clinical history of high-grade fever and chills within a month after a straightforward aortic valve replacement with known absence of coronary artery disease includes, firstly, a transesophageal echocardiography [5]. It has a sensitivity and a specificity for abscess detection of 87% and 95%, respectively [2]. Coronary angiogram in this particular patient was indicated based on a misdiagnosis of coronary artery disease. Although the angiographic appearance is typical (complex and long lesion that often disappears on diastole), a coronary angiogram should be avoided because it may cause dislodgement of septic fragments, which fortunately did not occur in this particular case.

5. What are the most likely mechanisms responsible for myocardial infarction during infective endocarditis?

The present case describes a rare complication of prosthetic valve endocarditis, an aortic root abscess causing external coronary artery compression and acute myocardial infarction. Acute coronary syndromes are uncommon in prosthetic valve endocarditis, with a prevalence of between 1% and 3% [1]. The most likely mechanisms responsible for myocardial ischemia during infective endocarditis are the presence of preexisting coronary artery disease and coronary emboli from aortic vegetations. Other less frequent mechanisms have been described, such as obstruction of the coronary ostium due to large vegetation and severe aortic insufficiency [1, 3]. External coronary artery compression due to infective endocarditis is also a described mechanism but is a rare occurrence with only a few cases reported in medical literature [3, 9].

6. Why did this patient receive empiric antibiotic therapy?

The isolation of the causative organism of prosthetic valve endocarditis is essential, and antibiotic therapy should be delayed pending the blood culture results in cases of patients who are hemodynamically stable with an indolent clinical course. However, patients presenting hemodynamic instability or acute disease should receive empiric broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy promptly [7]. Therapy should be subsequently adjusted according to the culture results. The American Heart Association (AHA) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines recommend that prosthetic valve endocarditis should be treated for at least 6 weeks with an adequate bactericidal agent.

7. How do you justify the urgent operation despite the patient’s condition?

Although the patient was a very high-risk surgical candidate, the urgent operation was justified due to patient’s age and treatable heart problems, despite the presence of active infection, aortic root invasion, and abscess.

8. How should the patient be managed in the urgent operation?

The operation was performed with the aid of hypothermic cardiopulmonary bypass with aortic and bicaval cannulation. Myocardial protection was achieved with cold blood cardioplegia delivered through the coronary ostium and coronary sinus. An oblique aortic arteriotomy revealed a large anterior aortic root abscess, which had invaded the left and right coronary cuspids. The bioprosthesis was removed, and the abscess was evacuated; complete debridement of all infected material was also performed. Both coronary buttons were carefully mobilized and cleaned of all infected tissue. The aortic annulus was severely destroyed by the infection. Aortic root replacement with cryopreserved homograft was performed using interrupted monofilament sutures. The coronary buttons were directly reimplanted on the homograft with continuous sutures. The aortic-to-right-atrium fistula was closed with an autologous pericardium patch. Additionally, a coronary artery bypass grafting with a reversed saphenous vein graft to left anterior descending artery was performed. Prolonged cardiopulmonary bypass and mediastinal bleeding were problems in the operating room, requiring vigorous transfusion and delayed chest closure on the next day. Cultures drawn in the operating room were negative.

Change history

22 March 2019

This chapter was inadvertently published with incorrect order of Given name and Family name for the author “Armindo Jreige Júnior” and the name has been updated to correct order –

Bibliography

Attias D, Messika-Zeitoun D, Wolf M, Lepage L, Vahanian A. Acute coronary syndrome in aortic infective endocarditis. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2008;9:727–8.

Daniel WG, Mugge A, Martin RP, Lindert O, Hausmann D, Nonnast-Daniel B, Laas J, Lichtlen PR. Improvement in the diagnosis of abscesses associated with endocarditis by transesophageal echocardiography. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:795–800.

Harinstein ME, Marroquin OC. External coronary artery compression due to prosthetic valve bacterial endocarditis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;83:E168–70.

Hoen B, Duval X. Infective endocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:785.

Horton CJ Jr, Nanda NC, Nekkanti R, Mukhtar O, Mcgiffin D. Prosthetic aortic valve abscess producing total right coronary artery occlusion: diagnosis by transesophageal three-dimensional echocardiography. Echocardiography. 2002;19:395–8.

Mansur AJ, Grinberg M, Da Luz PL, Bellotti G. The complications of infective endocarditis. A reappraisal in the 1980s. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:2428–32.

Manzano MC, Vilacosta I, San Roman JA, Aragoncillo P, Sarria C, Lopez D, Lopez J, Revilla A, Manchado R, Hernandez R, Rodriguez E. Acute coronary syndrome in infective endocarditis. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2007;60:24–31.

Millaire A, Van Belle E, De Groote P, Leroy O, Ducloux G. Obstruction of the left main coronary ostium due to an aortic vegetation: survival after early surgery. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:192–3.

Zoffoli G, Gherli T. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Periaortic valve abscess presenting as unstable angina. Circulation. 2005;112:e240–1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Jreige Júnior, A., de Oliveira, F.B.M., Schloicka, L.L., Atik, F.A., da Cunha, C.R. (2019). Unusual Mechanism of Myocardial Infarction in Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis. In: Almeida, R., Jatene, F. (eds) Cardiovascular Surgery. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57084-6_16

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57084-6_16

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-57083-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-57084-6

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)