Abstract

Youth (adolescents and young adults) constitute one of the highest risk groups for STI and HIV acquisition and transmission as well as unintended pregnancy. As they are in a unique period of development, youth are both biologically and cognitively susceptible to acquisition of STIs. HIV-positive youth, both those who are perinatally-infected (PHIV) and behaviorally-infected (BHIV), are at particular risk for STI acquisition and transmission although sexual risk behaviors and STI incidence and prevalence differ between these groups. Although screening, prevention, management, and treatment recommendations for STIs in HIV-coinfected youth do not differ from recommendations for HIV-coinfected adults, a special awareness of the psychological complexity and the social milieu of adolescence is key to providing optimal care and preventing acquisition of STIs and transmission of HIV to partners of youth infected with HIV.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Adolescents

- Young adults

- Youth

- HIV/AIDS

- Sexual health

- STI

- Sexually transmitted infections

- Contraception

- Risk behaviors

- Screening

- Prevention

Introduction

Youth are at high risk for acquisition and transmission of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV as well as unintended pregnancy. Youth in developed countries including Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Sweden, and the United States have generally similar rates of sexual activity; however, American youth have higher rates of pregnancy, childbearing, abortion, and STIs [1]. These rates are affected by various factors including negative societal attitudes toward teenage relationships and sexuality, restricted access to and high cost of reproductive health services, indecision regarding contraception, and lack of motivation to avoid pregnancy [1]. High rates of STIs among U.S. youth are associated with an increased number of sexual partners, lower levels of condom use, and complexity of their sexual networks [2].

HIV-infected youth represent a heterogeneous group in terms of sociodemographics, mode of HIV infection, sexual and substance abuse history, clinical and immunologic status, psychosocial development, and readiness to adhere to medications. Success in the treatment and prevention of pediatric HIV has completely changed the epidemic in high-resource countries, and perinatally-infected children can now survive into adulthood with appropriate care [3]. However, among U.S. youth aged 13–24 years living with HIV, the majority acquired their infection through high-risk behaviors, not through perinatal exposure [4].

Youth are in a unique period of development—their psychosocial developmental stage is normally associated with increased risk-taking behaviors and desire for autonomy [5], a key part of why they are so susceptible to STIs. Those who are HIV-positive can then enter into a “perfect storm” for additional STI acquisition, transmission, and related complications. STIs are known to enhance HIV shedding at mucosal sites, therefore increasing the infectiousness of the HIV-positive individual. In addition, STIs can have a more rapid and severe course in infected and immunosuppressed youth [6]. This review, therefore, focuses upon the epidemiology of sexual behaviors and STIs, biological and cognitive susceptibility to STI acquisition, STI screening and vaccination recommendations, and STI treatment and management considerations, in the key population of HIV-positive youth living in the U.S. Two case examples are also provided to illustrate intertwining STI/HIV risks and acquisition in high-risk youth.

Epidemiology of Sexual Behaviors and STIs in HIV+ Youth

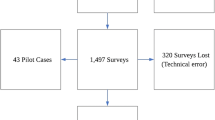

As mentioned above, in the United States, two distinct cohorts of HIV-infected youth exist—those who acquired disease perinatally (PHIV-infected youth), and those who acquired the disease behaviorally (BHIV-infected youth), usually through sexual contact or injection drug use. Figure 14.1 presents the estimated distribution of youth and young adults aged 13–24 years living with diagnosed HIV infection at the end of 2014 by sex and transmission category, in the United States and six dependent areas [4].

Adolescents and young adults aged 13–24 years living with diagnosed HIV infection by sex and transmission category, year-end 2014—US and 6 dependent areas. From CDC, HIV surveillance in adolescents and young adults (through 2015). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/slidesets/cdc-hiv-surveillance-adolescents-young-adults-2015.pdf

Among male youth living with diagnosed HIV infection at the end of 2014 (N = 29,115), 80% of infections were attributed to male-to-male sexual contact. An estimated 12% had infection attributed to perinatal exposure. Three percent were attributed to heterosexual contact, 3% to male-to-male sexual contact and injection drug use, and 1% to injection drug use. One percent of males aged 13–24 had infection attributed to other transmission categories (including hemophilia, blood transfusion, or unreported/unidentified factors). Among adolescent and young adult females in the same time period (N = 9,241), 49% of infections were attributed to heterosexual contact. An estimated 42% of females aged 13–24 were living with diagnosed HIV infection attributed to perinatal exposure. Five percent were attributed to injection drug use, and 4% had infection attributed to other transmission categories as described above.

Risk and Protective Sexual Behaviors

Sexual risk behaviors have been examined separately in PHIV-infected and BHIV-infected youth. Carter et al. reviewed 32 articles published from 2001 to 2012 that described prevalence, correlates, and characteristics of sexual activity, HIV status disclosure, and contraceptive and condom use among U.S. infected youth aged 10–24 years [7]. By definition, most BHIV-infected youth (89% in one reviewed study) were sexually active in the previous year; 68–72% were sexually active in the preceding 3 months. A smaller proportion of PHIV-infected youth (both males and females) were sexually experienced (estimates ranged between 25 and 46%), and initiation of penetrative sex appeared to be slower compared to HIV-uninfected but PHIV-exposed youth, particularly for youth with HIV+ caregivers. However, one correlate of sexual initiation in PHIV-infected youth included antiretroviral non-adherence (among adults it has been suggested that this association may be related to hopelessness) [8]. Positive correlates of recent sexual activity in HIV-infected youth included acquiring HIV behaviorally (as compared to perinatally), drug and alcohol use, greater HIV knowledge, and physiological anxiety (as opposed to health-related anxiety). Those with mid-level CD4 counts (as opposed to very low or high CD4 counts) were less likely to be currently sexually active [7].

Partner concurrency has been identified as an issue in HIV-infected youth. Concurrency is a situation in which more than one sexual partnership is occurring simultaneously (in contrast to serial monogamy, in which each partnership must end before the next starts) [9]. A larger proportion of young BHIV-infected men who have sex with men (MSM) compared to BHIV-women who have sex with men (WSM) reported sex partner concurrency (56 vs. 36%); these numbers contrast sharply with the 14% concurrency rate reported in sexually active adolescents in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health [10]. Sexually active BHIV-infected female youth reported a mean of 1.8–1.9 partners in the previous 3 months; the same studies indicated that these young women thought their partners were also having other partners 22–36% of the time [7]. Concurrency is described in more detail below (see Biological and Cognitive Susceptibility to STI Acquisition).

Condom use and serostatus disclosure have been explored as protective factors. In general, condom use in PHIV-infected youth was more common compared to HIV-uninfected peers, but many PHIV-infected youth (65%) still reported ever having had condomless sex [7]. In studies of BHIV-infected youth, estimates of recent condomless sex ranged from 40 to 63%, with lower rates of condom use at last sex reported in WSM versus MSM (61 vs. 78%) [10]. Serostatus disclosure to recent sex partners estimates range from 20 to 60%, for both BHIV and PHIV-infected youth, and has been associated with fewer numbers of sex partners, the partner being primary/main versus casual, the partner being perceived to have HIV, greater number of sex acts with a partner, greater length of time since HIV diagnosis, disclosure to friends and family, immunosuppression, and older age [7].

STI Incidence and Prevalence

STI incidence and prevalence have been examined separately in PHIV-infected and BHIV-infected youth. In a cohort of 174 sexually active PHIV-infected adolescent girls aged 13–19 years, estimated cumulative incidences for STIs over a 6-year time period were calculated to be condyloma 8%, trichomoniasis 7%, genital chlamydia infection 6%, genital gonorrhea 4%, and syphilis 2%. Only 58% had a Pap test, but of those who did, 47.5% of the sexually active adolescents had abnormal cytology (30% occurred at first exam) [11]. Only one other pilot study in the U.S. has examined HPV in PHIV-infected children: of 23 PHIV-infected non-sexually active girls, 30 and 17% had anogenital and oral HPV (mostly high-risk types), respectively; of 23 PHIV-infected non-sexually active boys, 17 and 4% had anogenital and oral HPV, respectively (again, mostly high-risk types). Sexual activity was defined as oral, vaginal, anal or genital–genital contact in this study [12].

In BHIV-infected youth, one study of 143 BHIV-infected females aged 13–24 years screened over 18 months for genital chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, and syphilis calculated overall STI incidence to be 1.4/100 person-months, not significantly different between the high and low viral load groups. This was thought to be lower than previously published estimates from high-risk non-HIV-infected youth. However, after initial diagnosis, 8/27 participants were diagnosed with 1 additional STI, indicative of ongoing sexual risk behaviors in a subset of the population [13].

The Reaching for Excellence in Adolescent Care and Health (REACH) study enrolled 346 BHIV-infected adolescents (257 girls and 89 boys) aged 12–18 years compared to 182 (142 girls and 40 boys) HIV-uninfected but same-aged, at-risk sexually active adolescents matched for drug-taking behaviors. Enrollment took place from 1996 to 2000 from 16 clinical sites around the U.S., and provided valuable longitudinal information about BHIV-infected adolescents as compared to high-risk peers. Incident trichomoniasis (1.3 vs. 0.6/100 person-months) and genital chlamydia infection (1.6 vs. 1.1/100 person-months) were significantly higher in BHIV-infected girls, though genital gonorrhea was not (0.6 vs. 0.4/100 person-months) [14]. Younger age was associated with STIs in both the BHIV-infected and HIV-uninfected girls. Incidence of genital gonorrhea was borderline significantly higher in BHIV-infected boys (0.8 vs. 0.2/100 person-months); genital chlamydia incidence was not (1.3 vs. 0.8/100 person-months), probably owing to the small number of male participants. No studies on STI incidence in BHIV-infected youth incorporated extragenital testing, so all of the above estimates are likely underestimates of true STI incidence that should also include oral or rectal infections.

In the REACH study, viral STI detection rates, specifically for HPV infection, were also significantly different in the BHIV-infected adolescents compared to the HIV-uninfected, at-risk sexually active adolescents. At baseline, 103 of 133 (77%) BHIV-infected girls, compared with 30 of 55 (55%) HIV-uninfected girls, were positive for HPV (predominantly high-risk types) from cervical lavage samples [15]. Prolonged persistence of either prevalent or incident HPV infection (measured every 6 months) was identified in BHIV girls (689 vs. 403 days, respectively); this persistence was associated with CD4 immunosuppression and the presence of multiple HPV types [16]. Patterns of HPV-type infection, clearance, and persistence did not differ in this cohort of girls before or after the introduction of HAART, but the median follow-up time after HAART initiation in the study was 428 days (since 70–90% of HPV infection in healthy women clears between 12 and 24 months, the authors speculated the study’s 13-month follow-up time was too short to observe a significant difference in HPV clearance following HAART initiation) [17]. In terms of anal HPV, the BHIV-infected adolescents initially had a higher prevalence of anal HPV infection compared to the HIV-uninfected adolescents (girls: 59/183 (32%) versus 11/82 (13%) respectively; boys: 28/58 (48%) versus 9/25 (36%), respectively). HIV infection was independently associated with prevalent abnormal anal cytology results in the boys [18]. When followed annually over time, BHIV-infected girls had a significantly higher incidence of anal HPV versus high-risk HIV-uninfected girls (30 vs. 14 per 100 person-years), high-risk anal HPV (12 vs. 5.3 per 100 person-years), and anogenital warts (6.7 vs. 1.6 per 100 person-years); anal dysplasia was also more common but not statistically significantly different (12 vs. 5.7 per 100 person-years). Incident HPV and HPV-related events were consistently higher in the BHIV-infected boys versus high-risk uninfected boys [anal HPV (40 vs. 24 per 100 person-years), high-risk anal HPV (27 vs. 11 per 100 person-years), anogenital warts (8.8 vs. 1.2 per 100 person-years), and anal dysplasia (37 vs. 13 per 100 person-years)] but did not achieve statistical significance likely due to the small number of boys followed [19].

Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C infection has also been examined in the REACH study [20]. BHIV-infected males were more likely to have evidence of HBV infection (defined as a positive HBV core antibody) than HIV-uninfected males (23.7 vs. 0%, respectively, P = 0.008). No significant difference was found for HBV infection in BHIV versus HIV-uninfected females (17.4 vs. 8.4%, respectively, P = 0.112). The rate of HCV infection (1.6%) (defined by positive EIA confirmed by repeat EIA, recombinant immunoblot, or PCR) was too small to make comparisons between groups. A significant risk factor for HBV infections for males was a homosexual or bisexual orientation. For females, a risk factor for HBV infection was having more than 10 lifetime sexual partners. In addition, in the HIV-infected cohort, 15% of females and 36% of males who were seropositive for HBV had evidence of active HBV infection (defined as a positive HBV surface antigen); none of the HIV-uninfected subjects who were seropositive for HBV had evidence of active HBV infection.

Biological and Cognitive Susceptibility to STI Acquisition in HIV+ Youth

Youth are susceptible to acquisition of STIs based on several biological and cognitive/behavioral characteristics. In HIV-positive youth, STIs can promote increased HIV shedding and transmission to partners, making these characteristics particularly important.

Biological Factors

The female genital tract has a greater surface area than the male genital tract and a larger amount of semen compared to vaginal fluids is involved in intercourse [21, 22]. This accounts for some of the increased risk for female acquisition of HIV and other STIs. During puberty, the vaginal flora pH decreases and becomes more acidic secondary to the appearance of Lactobacillus species, though the relationship between this change and risk of STIs has not yet been clarified [23]. The cervix of female adolescents is lined by immature single-layered columnar epithelium, or cervical ectopy (also termed ectropion), which is more susceptible to infection compared to the multilayered squamous epithelium of adult women. Epidemiologic studies have found a specific association between ectopy and infection with Chlamydia trachomatis, as this organism resides in and favors columnar epithelial cells [24,25,26]. Neisseria gonorrhoeae may also attach preferentially to columnar epithelium rather than squamous tissue [27]. Persistence of ectopy has been associated with use of hormonal contraceptives (including both oral and injectable methods) which is of particular concern in female youth, many of whom utilize these medications [28].

The vasculature within columnar epithelium of ectopy is more superficial and more easily traumatized than that of squamous epithelium, theoretically permitting HIV-infected cells from the circulation to gain access to the mucosal surface, and for infected monocytes and lymphocytes to reach the circulation [23]. Ectopy has been associated with increased risk for HIV acquisition in uninfected women in some studies, particularly in the youngest age groups, although this remains controversial [29,30,31]. In one particular study of HIV-infected versus uninfected adolescent women, an independent association between HIV infection and increased ectopy was not shown [32].

Compared to older women, adolescent women have less estrogenization of the genitalia, thinner cervical mucus, and poor lubrication with intercourse-related trauma, all increasing their risk of STI acquisition. In addition, thinner mucus may permit organisms to penetrate more easily and to attach to mucosal sites or gain access to the upper reproductive tract of young women [23]. In a study of adolescent women and cytokine profiles in cervical secretions, lower concentrations of IL-10 were noted in HIV-uninfected versus HIV-infected subjects coinfected with HPV. The lower concentrations of IL-10 in the HIV-uninfected subjects reflected an appropriate response (shift from antibody-mediated genital immune environment to T cell-mediated immune response in the context of a viral infection). Concentrations of IL-12 (which enhances the cell-mediated response) were associated with HIV and HPV infections and presence of another STI (including C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae and/or T. vaginalis). Thus, compared to their HIV-uninfected counterparts, in HIV-infected adolescent women there was a change in the local immune environment after secondary infection with viruses, bacteria, or protozoans [33].

Lastly, compared with adults, youth differ in their timing of acquisition and response to HIV infection. For those with BHIV, youth are more likely than adults to be relatively recently infected [34]. Once infected, youth have persistence of thymic function; this allows for naïve T cell generation and a greater capacity for reconstitution especially in the context of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) [35,36,37,38]. Of note, young women tend to have lower viral loads compared to young men despite comparable CD4 cell counts [39].

Cognitive/Behavioral Factors

Several aspects of adolescent development make youth more susceptible to STIs compared to their adult counterparts, and these are magnified in those infected with HIV. Those aged 14–17 years (middle adolescence) in particular may believe in the “myth of invulnerability,” or that in the case of STIs, infections might occur to others but not to them. Youth also tend to be less knowledgeable regarding signs and symptoms of STIs and may be afraid to disclose their diagnosis and/or sexual activity to guardians or parents [28]. Peers and friends with whom youth associate may have a significant effect on their behavior and sexuality. For example, youth who believe that their friends are sexually active are more likely to become sexually active themselves, and having sexually active friends has been associated with earlier sexual debut among both boys and girls, controlling for a variety of social and demographic factors [40, 41].

Behavioral factors increasing the risk of acquisition of STIs in youth include having new, recent and/or multiple sexual partners; older age partners; partners who engage in high-risk behaviors (intravenous drug use); douching; drug use (including illicit and intravenous drugs, tobacco, and alcohol); and a past history of STIs [28]. Mood disorders and drug use are both common among youth. In those with a chronic illness such as HIV, depression is often secondary to long-term disease-related stressors and challenges, increasing the risk for substance use and abuse and thus STI acquisition [42, 43]. Furthermore, in a study of 166 HIV-infected youth aged 13–21 years in three US cities, a larger proportion of participants with BHIV compared to PHIV reported lifetime use of alcohol, marijuana, tobacco, and club drugs. Of note, this difference was not solely due to age [44]. This is consistent with national data demonstrating high rates of drug use among youth at risk for HIV in the first place [45].

As mentioned previously, concurrency is a key issue in HIV-positive youth. Since youth typically have more relationship partners than adults, sexual networks and concurrency are particularly important in this population and underlie the generally increased risk for STIs that youth face [46]. Concurrency amplifies the transmission of STIs and HIV by reducing the time between transmissions. By linking individuals together to create a large network, it removes any protection that would be afforded by monogamy, and pathogens can travel efficiently and rapidly throughout the population [47,48,49,50].

Age mixing of couples is an additional factor influencing the prevalence of curable and incurable STIs and one particularly relevant to youth. For example, age mixing is often asymmetric among heterosexual couples, with males being typically older than their female partners. Sex-based and economic power differentials may underlie the types of sexual relationships young women engage in, especially with older men, who may be more likely to be infected with HIV and other STIs in the first place [28, 51, 52]. In this way, such females will become infected earlier than their male age peers, as seen with HIV in many sub-Saharan African countries and in curable STIs in the US [9, 23]. Similar age mixing has also been shown to influence the spread of HIV among men who have sex with men [53, 54].

STI Screening and Vaccination Recommendations in HIV+ Youth

Close screening and follow-up is recommended for all of the STIs in HIV-positive youth because of their risk factors and because they are at increased risk to transmit their HIV. Recommendations from the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Disease Society of America, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Disease Society of America are all applicable to this age group [55,56,57,58,59,60].

Gonorrhea, Chlamydia, and Syphilis Infections

All HIV-infected women aged <25 years should be screened for chlamydia and gonorrhea. HIV-infected youth should be screened for gonorrhea and chlamydia infection at initial presentation to care and then annually if at risk for infection; and for syphilis at care entry and periodically thereafter depending on risk factors [56, 57]. HIV-infected MSM are recommended to have even more frequent screening at 3–6 month intervals at all exposed anatomic sites (urethra, rectum, and oropharynx) if risk behaviors persist, if they or their sex partners have multiple partners, or if an STI is identified [57]. Secondary to high reinfection rates, rescreening in three months is indicated in men and women found to be positive for gonorrhea or chlamydia infections [57].

Optimal detection of genital tract infections caused by C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae in men and women is achieved with the use of nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) which have superior sensitivity and adequate specificity compared to older nonculture and non-NAAT methods. These FDA-cleared and recommended tests can be collected via vaginal (provider-collected vs. patient-collected) or cervical swabs from women and first-catch urine from women or men [61]. However, first-catch urine from women may detect up to 10% fewer infections when compared with vaginal and cervical specimens [62,63,64]. Specimens obtained with a vaginal swab are the preferred type for female screening; they are as sensitive and specific as cervical swab specimens [63,64,65,66,67,68]. Urine is the preferred specimen type for male urethral screening [62]. While NAATs have not been cleared by the FDA for the detection of rectal and oropharyngeal infections, CDC recommends this testing based on increased sensitivity and ease of specimen transport and processing. Most reference laboratories have already performed internal validation for such testing which is now commercially available [62]. Table 14.1 shows the current FDA-approved platforms for NAAT testing of chlamydia and gonorrhea and the approved age ranges as relevant to youth.

Trichomoniasis

Unlike in HIV-uninfected patients, sexually active HIV-positive women should be screened for trichomoniasis at care entry and then at least annually thereafter. This is based on studies of women 18–61 years of age regarding the role of this organism in HIV transmission and the ability of trichomonas treatment to reduce genital HIV-1 shedding even in women not on antiretroviral therapy [69,70,71,72]. In addition, secondary to high reinfection rates, retesting in 3 months is indicated in women with trichomoniasis.

A few platforms offer sensitive and specific testing for trichomonas. NAAT has the highest sensitivity and acceptable specificity and is available for women only from vaginal, endocervical or urine specimens; however, the APTIMA assay may be used with male urine or urethral swabs if validated per CLIA regulations. Table 14.1 shows the current FDA-approved platforms for NAAT testing of trichomonas and the approved age ranges as relevant to youth.

Other FDA-cleared tests to detect T. vaginalis in vaginal secretions include the OSOM®Trichomonas Rapid Test (Sekisui Diagnostics, Framingham, MA) which relies on immunochromatographic antigen detection of T. vaginalis in vaginal secretions. This CLIA-waived point-of-care test provides results in 10 min, with a sensitivity of 82–95% and specificity of 97–100%. The AffirmTM VP III (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) is a DNA hybridization probe test that evaluates for T. vaginalis, Gardnerella vaginalis, and Candida albicans in vaginal secretions. Trichomonas test sensitivity is 63% and specificity is 99.9%, and results are typically available in 45 min. However, methods for T. vaginalis diagnosis including the DNA hybridization probe test, wet mount, or culture have lower sensitivity and specificity and are not recommended as first-line screening tests if amplified molecular detection methods are available [57].

Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

High rates of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) persistence occur in all women with HIV infection and most women are first infected during adolescence. This has important implications for future development of invasive cancer. Thus, HIV-infected women should be screened for cervical cancer with a cervical Pap test within 1 year of sexual debut regardless of mode of HIV acquisition, but no later than age 21, since HIV positive sexually active women <21 years have a high rate of progression of abnormal cytology. The Pap test can be repeated at 6 months (and should occur twice in the first year after initial HIV diagnosis) but typically is repeated annually if baseline results are normal. HPV co-testing is currently not recommended for women younger than 30 years of age, but reflex HPV testing is indicated if ASCUS (atypical squamous cells of uncertain significance) is found on Pap smear [58].

Lastly, all HIV-positive individuals should be vaccinated against HPV at ages 13 through 26 with bivalent, quadrivalent or nonavalent vaccine in a three-dose series, if these individuals did not receive an age-appropriate number of doses when they were younger [58,59,60].

Viral Hepatitis

HIV-infected patients should be screened for evidence of Hepatitis B infection upon entry to care (via detection of surface antigen, surface antibody and antibody to Hepatitis B core antigen). Those who are susceptible to infection should be vaccinated. Surface antibody testing should be performed 1–2 months following vaccine series completion, and a repeat series of vaccine should be considered for those who are nonimmune despite vaccination. Vaccination should also be reviewed and recommended for nonimmune sexual partners of those who are positive for Hepatitis B surface antigen. Lastly, patients who are positive only for anti-HepB core can be tested for chronic infection via HBV DNA and those without chronic infection should be vaccinated [56, 59, 60].

All HIV-positive patients should be screened for Hepatitis C infection via antibody testing; annual screening should be done for those who remain at risk. Those with positive antibody should be tested for HCV RNA to assess for active disease [56]. However, because a small percentage of HIV-infected patients do not develop antibody, RNA testing should also be considered for those with negative antibody and unexplained liver disease [57].

Hepatitis A vaccination is recommended for all susceptible men who have sex with men (including youth and adults) and others susceptible to disease (injection drug users, persons with chronic liver disease, travelers to countries with high endemicity or patients coinfected with other viral hepatitides). Hepatitis A total or IgG antibody testing should be done at 1–2 months after vaccination, and repeat series is recommended in seronegative individuals [56, 59, 60]. Limited data show that vaccination of those with advanced HIV or chronic liver disease may result in lower antibody concentrations and vaccine efficacy. In addition, in those with HIV, antibody response can be directly related to CD4+ levels [58].

STI Management and Treatment Considerations in HIV+ Youth

General Concerns About Treatment, Counseling, Confidentiality, and Sexual History-Taking

Important differences in STI treatment in HIV-infected youth exist as compared to their uninfected counterparts. For example, treatment for bacterial STIs is largely similar in both HIV-positive and negative patients, but follow-up testing is generally more frequent in HIV-infected patients. Viral and parasitic STIs may need a longer treatment duration in HIV-infected patients. Additional issues to consider during STI treatment for both HIV-infected youth and adults include condom use (e.g., clindamycin cream for treatment of bacterial vaginosis may weaken condoms, making them less useful for prevention of HIV/STI transmission and unintended pregnancy), alcohol use (e.g., importance of avoidance during treatment with nitroimidazoles), and risk of pregnancy while on STI therapy (e.g., implications of becoming pregnant while on potentially teratogenic HIV treatment regimens and transmission of STIs to the fetus).

In regards to counseling youth during STI management, clinicians must be nonjudgmental, use youth-oriented terminology and language, and be aware of motivational issues which worsen barriers to healthcare access. Youth already face multiple barriers to accessing quality STD prevention and management services including inability to pay, lack of transportation, long waiting times, conflicts between clinic hours and work/school schedules, and embarrassment attached to seeking STD services [73]. Concerns about confidentiality are particularly important when caring for minors. Laws in all fifty states and the District of Columbia allow minors to consent to testing and treatment for sexually transmitted diseases without parent/guardian notification, but states may have differing laws regarding HIV testing or treatment. For example, California, New Mexico, and Ohio limit authorization to HIV testing but not treatment, and Iowa requires that parents be notified should their child test positive for HIV [74]. Clinicians must be familiar with state-specific laws in order to counsel and reassure minors about confidential services. Youth are likely to feel more confident and comfortable disclosing their sexual history and risk factors to a clinician if they can be assured of confidentiality as the law allows. It is important to recognize that while medical professionals including students report comfort with sexual history-taking, they report discomfort and lack of confidence in discussing sex and sexuality with youth [75, 76]. At the same time, adolescents frequently find it difficult to initiate sexual health discussions with adults, including clinicians, and prefer that clinicians bring up these sensitive topics [77,78,79]. An observational study of audio-recorded conversations between 253 adolescents and 49 pediatricians at 11 clinics in North Carolina found that while 65% of all visits contained some sexual health content, the average time devoted to this content was only 36 s, and only 4% of adolescents had prolonged conversations with their physicians [80]. Of note, adolescents never initiated sexuality talk and often were reluctant to engage beyond minimal responses to direct questions. These findings are concerning for missed opportunities to educate and counsel adolescent patients on healthy sexual behaviors and prevention of sexually transmitted diseases and unplanned pregnancy.

Syphilis Infection

Syphilis treatment recommendations for HIV-infected individuals do not differ from the stage-based recommendations given for non-HIV-infected individuals, as no treatment regimen has proven more efficacious than the standard regimens given for HIV uninfected patients. Moreover, no adolescent or young adult-specific data exist. Primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis are treated with benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units IM in a single dose; late latent and tertiary syphilis are treated with benzathine penicillin G in weekly doses of 2.4 million units IM for 3 weeks; neurosyphilis (including ocular or otic syphilis) is treated with aqueous crystalline penicillin G 18–24 million units per day, administered as 3–4 million units IV every 4 h or continuous infusion, for 10–14 days. The efficacy of non-penicillin-based regimens in HIV-infected individuals is unknown [81].

Although the interpretation of treponemal and nontreponemal serologic tests for persons with HIV infection is the same as for the HIV-uninfected patient, unusual serologic responses (high serofast, fluctuating false-negative serologic tests, delayed appearance of seroreactivity) have been reported in HIV-positive individuals. Moreover, HIV-infected individuals are followed more closely following treatment: primary and secondary syphilis-HIV coinfected patients should be evaluated clinically and serologically for treatment failure at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 months (not just at 6 and 12 months); latent syphilis-HIV coinfected patients should be evaluated clinically and serologically for treatment failure at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months (not just at 6, 12, and 24 months). If at any time, clinical symptoms develop or a sustained (>2 weeks) fourfold or greater rise in nontreponemal titers occurs, CSF examination should be performed and treatment administered accordingly. If nontreponemal titers do not decline fourfold within 12–24 months of primary or secondary syphilis, or after 24 months after treatment for latent syphilis, CSF examination and treatment can be considered.

Gonorrhea and Chlamydia Infections

Gonorrhea and chlamydia treatment recommendations for HIV-infected individuals do not differ from those given for non-HIV-infected individuals. Uncomplicated anogenital and pharyngeal gonococcal infections should be treated with single doses of ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscularly and azithromycin 1 g orally. Dual therapy is recommended to improve treatment efficacy and potentially slow the emergence and spread of cephalosporin resistance. Importantly, doxycycline (rather than azithromycin) is no longer recommended as part of dual therapy based on substantially higher prevalence of gonococcal resistance to tetracycline than to azithromycin among isolates in the United States [57]. If ceftriaxone is not available, then cefixime 400 mg can be given orally in a single dose in addition to azithromycin; however, this regimen is not appropriate for pharyngeal infections as cefixime has limited treatment efficacy in this situation (92.3% cure (95% CI = 74.9–99.1%) compared to 97.5% cure (95% CI = 95.4–99.8%) in anogenital infections) [82, 83]. A test of cure is only needed for individuals with pharyngeal gonorrhea treated with an alternative regimen; either culture or NAAT should be performed 14 days after treatment and any positive testing should be followed by antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Limited data exist regarding alternative treatment regimens for those with cephalosporin or IgE-mediated penicillin allergy, but may include dual treatment with oral gemifloxacin and azithromycin or intramuscular gentamicin and azithromycin; spectinomycin may also be used for anogenital gonorrhea if available [57].

Treatment for chlamydia infection includes either azithromycin 1 g orally in a single dose or doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days. Alternative regimens include 7-day regimens of oral erythromycin base (500 mg four times daily), erythromycin ethylsuccinate (800 mg four times daily), levofloxacin (500 mg once daily) or ofloxacin (300 mg twice daily). Of note, although routine screening of chlamydia from oropharyngeal sites is not recommended, it can be sexually transmitted from oral to genital sites [84, 85]. Thus, chlamydia detected from the oropharynx should be treated with one of the above-recommended regimens. The efficacy of any of the alternative regimens, however, is unknown for this indication [57]. Lastly, more recent retrospective studies have raised some concern about the efficacy of azithromycin for rectal chlamydia infections [86, 87]. However, more studies are needed comparing azithromycin and doxycycline before definitive recommendations can be made in this regard [57].

Although pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) treatment regimens do not differ between HIV-infected and uninfected individuals (a single dose of a third generation cephalosporin should be combined with 14 days of doxycycline, to be used with or without 14 days of additional anaerobic coverage with metronidazole), decisions surrounding inpatient versus outpatient management are more complicated in youth. Even in the absence of general inpatient admission criteria for PID such as high fevers and toxicity, pregnancy or inability to tolerate oral medications, or tubo-ovarian abscess, some adolescents may still warrant inpatient admission. Though the PEACH (Pelvic Inflammatory Disease Evaluation and Clinical Health) Trial is often cited as evidence supporting the idea that females with mild to moderate PID can be treated as outpatients safely and effectively, the mean of those participants younger than 19 years was 17.8 years, reducing the generalizability of the study to all adolescent populations [88]. Specifically, as mentioned above, those adolescents younger than 17 years are particularly impacted by the “myth of invulnerability” and developmental stage may hinder medication compliance if parent/guardian guidance or other supports are absent. Determination of whether youth can comply with outpatient management should be based on developmental stage and availability of support systems, and youth should be closely followed by clinicians if outpatient therapy is prescribed, to ensure compliance.

Trichomonas

As mentioned previously, trichomonas plays a significant role in both the acquisition and transmission of HIV and thus HIV-positive women should be screened and treated if positive (see Screening) [56, 57, 70,71,72,73]. A randomized clinical trial of HIV-positive women 18 years and older (mean age 40.1 years, ±9.4 years) with trichomoniasis showed that a single dose of metronidazole (2 g orally) was less effective than 500 mg twice daily for 7 days [89]. Thus, in order to improve cure rates, we would also recommend that HIV-positive adolescent women should be treated with the one week course of therapy rather than the single-dose therapy [57]. Given the prevalence of underage drinking, avoidance of alcohol consumption while on metronidazole and for 24 h after completion of therapy should be explicitly addressed, even with adolescents.

Bacterial Vaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis recurs with higher frequency in women who have HIV infection [90]. In addition, BV increases the risk for HIV transmission to male sex partners [91]. However, current recommendations do not advocate for treatment of asymptomatic BV, and women with HIV who have BV should receive the same treatment regimen as those who do not have HIV infection (metronidazole 500 mg orally twice daily for 7 days, OR metronidazole gel (0.75%) 5 g intravaginally daily for 5 days, OR clindamycin cream (2%) 5 g intravaginally daily for 7 days) [57]. Again, given the prevalence of underage drinking, avoidance of alcohol consumption while on metronidazole and for 24 h after completion of therapy (72 h if an alternative regimen containing tinidazole is used) should be explicitly addressed, even with adolescents. A 2009 pilot study investigated whether treatment of asymptomatic BV would have any impact on HIV-1 shedding in the genital tract of 30 women (median age 42.5 years) already virally suppressed on HAART without coinfection with other STIs [92]. The women were randomly assigned in a non-blinded fashion to observation versus treatment with metronidazole. At one month of follow-up, while treatment with metronidazole decreased the rate of asymptomatic BV, there was no statistically significant difference in HIV-1 shedding. Further study is needed before treatment of asymptomatic BV can be recommended in HIV-positive women.

Herpes Simplex Virus

HIV-infected patients may have prolonged or severe episodes of genital, perianal, or oral HSV and HSV shedding is increased in these patients. While antiretroviral therapy reduces severity and frequency of symptomatic genital herpes, frequent subclinical shedding still occurs [93, 94]. Suppressive antiviral oral therapy can decrease the clinical manifestations of HSV in HIV-infected patients as shown in studies of individuals aged 21–63 years [95,96,97]. However, in studies of men and women including those as young as 18 years, suppressive therapy does not reduce the risk for either HIV or HSV-2 transmission to sexual partners [98, 99]. Regimens for first clinical episode of genital herpes do not differ between HIV-negative and HIV+ individuals (one of the following regimens for 7–10 days: acyclovir 400 mg orally three times daily, or acyclovir 200 mg orally five times daily, or valacyclovir 1 g orally twice daily, or famciclovir 250 mg orally three times a day); however, daily suppressive therapy and episodic treatment are generally higher dose and/or longer (5–10 days duration) in HIV-positive versus HIV-negative patients [57]. For severe HSV disease or complications that necessitate hospitalization (e.g., disseminated infection, pneumonitis, or hepatitis) or CNS complications (e.g., meningoencephalitis), the recommendation is for acyclovir 5–10 mg/kg IV every 8 h for 2–7 days or until clinical improvement is observed, followed by oral antiviral therapy to complete at least 10 days of total therapy.

Human Papillomavirus

Those with HIV are more likely to develop anogenital warts compared to those who are uninfected [100]. HIV-positive patients may also have larger or more numerous lesions, might not optimally respond to therapy, and tend to have more posttreatment recurrences [93, 101,102,103]. In addition, malignancies such as squamous cell carcinomas resembling anogenital warts are more frequent in those with HIV and may require biopsy [104,105,106]. Currently no data support altered genital wart treatment for HIV-positive patients compared to their HIV-negative counterparts [57, 58].

Viral Hepatitis

The course of liver disease is more rapid in HIV/HCV-coinfected persons and the risk of cirrhosis is nearly twice that of persons with HCV infection alone. Such patients receiving HIV therapy are typically treated for HCV after their CD4+ cell counts increase in order to optimize immune response [57]. Specific recommendations for management and treatment of Hepatitis C are available from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Disease Society of America [61].

Persons with acute hepatitis B receive supportive care. Those with chronic infection may be placed on treatment and can achieve sustained suppression of HBV replication and remission of liver disease [107]. HIV-infected patients should be screened and vaccinated as mentioned above (see Screening and Vaccination Recommendations). Additional recommendations for management of persons coinfected with HIV and HBV are available [100].

Patients with acute hepatitis A generally require only supportive care although those with acute liver failure or dehydration may require hospitalization. Vaccination in susceptible populations is described above (see Screening and Vaccination Recommendations).

Partner Management: General Guidelines

Maintaining the health of not only HIV-infected youth but also their partners is critical. For both BHIV- and PHIV-infected youth, anonymous HIV partner notification and contact tracing and HIV testing are available through and supported by the public health system in many states, and should be offered. However, systems may not be perfectly designed for dealing with youth-specific issues. For example, youth partner comprehension of the meaning of positive and negative HIV testing and window periods may vary by developmental stage as well as by level of health literacy, therefore disclosure and interpretation of test results may take longer. Because youth are in the process of asserting their independence, they often desire support from friends or family, while holding simultaneous fears of rejection or judgment. Clinicians should, therefore, take their cues from youth, and offer additional support in assisting HIV+ youth and their partners with disclosure to friends and family, if desired [108].

Expedited Partner Therapy

Expedited partner therapy (EPT) is the process by which a clinician provides medication or a prescription for a patient to distribute to his or her partner(s) for the treatment of STIs. EPT is legal in most states but varies by type of STI covered [57]. US trials and a meta-analysis of EPT have shown reductions in reinfection of index case-patients compared with patient referral differing according to the type of STI and the sex of the index case-patient; across trials, reductions in chlamydia and gonorrhea prevalence at follow-up were 20 and 50%, respectively [109,110,111,112]. These studies have included women as young as 14 years and men as young as 16 years of age. As a high-risk group for STI acquisition, youth could benefit greatly from this intervention; several national organizations, therefore, endorse EPT usage as a strategy to improve treatment and outcomes in youth [113,114,115,116]. However, the use of EPT in STI-HIV-coinfected youth has not specifically been investigated, as EPT usage would be limited by concerns about ongoing undiagnosed HIV infection in the partners of HIV-infected individuals who might or might not respond to advice to seek subsequent health care including STI/HIV testing.

HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is the preventive use of ART medications (specifically tenofovir-emtricitabine, or TDF-FTC) in HIV-negative patients at high risk for HIV acquisition. TDF-FTC was approved by the FDA in 2012 for PrEP in adults [117, 118]. CDC interim guidance for use was released for MSM in 2011, heterosexual adults in 2012 and injection drug users in 2013 [119,120,121]. Although the CDC PrEP guidance targets PrEP use in adults, TDF-FTC may be used off-label in those under 18 years of age. PrEP has been shown to be effective in reducing new HIV infections by 44–75% in adult MSM, heterosexuals and injection drug users taking daily PrEP [122,123,124,125]. PrEP has also been found to be an acceptable and feasible intervention in MSM as young as 18 years of age [126, 127]. The likely efficacy of TDF-FTC PrEP and immediate concerns about HIV acquisition in partners of HIV-infected youth should be balanced against data indicating that TDF-FTC adherence is lower in youth, and unknowns remain about impact on long-term bone mineral density or kidney function [128, 129]. Ongoing studies of PrEP in those under 18 years of age may lead to an indication for PrEP in younger youth in the near future.

While PrEP may be an effective HIV prevention method for both uninfected youth and discordant couples, barriers may exist to PrEP access. First, minors’ access to PrEP without parent/guardian consent is unclear, as demonstrated by a review of laws current as of December 2011 [130]. No state specifically prohibits minors’ access to PrEP or other HIV prevention methods and all states expressly allow some minors to consent to medical care for diagnosis or treatment of STIs. However, only eight jurisdictions allow consent to preventive or prophylactic services. Thirty-four states either allow minors to consent to HIV services or allow consent to STI or communicable disease services and classify HIV as an STI or communicable disease. Seventeen jurisdictions allow minors to consent to STI services, but they do not have a specific HIV provision and they do not classify HIV as an STI or communicable disease. Second, cost may also be a barrier for youth. While health insurance companies may cover PrEP, out-of-pocket costs may be up to $13,000 per year. Medicaid may cover PrEP depending on the state and medication may be covered via participation in clinical trials. Gilead, the manufacturer of tenofovir-emtricitabine, provides a co-pay assistance program which may help those eligible to cover the cost of co-pays.

Contraception and Family Planning Issues in HIV-Positive Youth

Family planning and reproductive healthcare are important issues for youth as they have a high rate of unintended pregnancies in general. As mentioned above, with the advent of effective antiretroviral therapy, PHIV-infected youth are surviving to adolescence and young adulthood. Thus, family planning becomes especially pertinent for both PHIV-infected and BHIV-infected youth particularly for prevention of perinatal disease.

Available studies show that reproductive health discussions with HIV-infected youth usually focus on STI prevention instead of family planning, and any pregnancy discussions tend not to occur in adolescents or in older women [131,132,133]. Clinicians may feel uncomfortable discussing sex and sexuality, and such barriers may prevent effective discussions surrounding family planning in HIV+ youth.

Importantly, drug interactions may occur between hormonal contraceptives and antiretroviral therapies, potentially increasing the risk of pregnancy in youth. Protease inhibitors can decrease the estrogen levels of combined hormonal oral contraceptives, and NNRTIs can either increase or decrease estrogen levels although the clinical significance of such effects are unknown [134, 135]. Failure of either drug or medication toxicities can occur in either situation. No such interactions occur between antiretroviral agents and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) or the levonorgestrel implant system [126]. Although case reports of failure of etonogestrel implants with efavirenz has been reported, neither the WHO or CDC recommend restrictions on any form of birth control in HIV-infected women [136,137,138].

Case Illustrations

Case 1

A 17-year-old African-American female presented to the Pediatric Infectious Diseases clinic for persistent posterior cervical and postauricular lymphadenopathy. She had been seen by her pediatrician five months prior for right-sided axillary lymphadenitis which was drained and grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; she had MRSA lymphadenitis on the left side four months prior to the current visit. Her current adenopathy was nontender with no overlying skin changes; she had no complaints of pain and was otherwise asymptomatic. She had a history of genital herpes and chlamydia twice in the last two years, both of which were treated appropriately. She reported condomless sexual intercourse with a male partner within the last three months and had negative STI screening for chlamydia, gonorrhea, HIV, and syphilis five months prior. Her periods were regular. Physical exam at the time of evaluation was remarkable for nontender cervical, pre/postauricular and inguinal adenopathy. Lab testing showed a normal CBC, ESR, CRP, and a negative PPD; as she had reported interaction with her grandmother’s new kitten, Bartonella and Toxoplasma titers were sent and negative as were EBV and CMV titers. RPR was nonreactive. HIV fourth-generation antibody/antigen testing was reactive; HIV viral load was 141K and CD4 count was 333 cells/mm3 (16%).

The patient and her mother were called back to clinic for disclosure of her diagnosis and the pediatrician requested support by the infectious diseases team during the disclosure process. Significant tension between the mother and patient was noted during the visit with some apathy from the patient toward her diagnosis, and overwhelming anger in the mother. The care team discussed HIV, evaluation, testing and follow-up and set up another visit for the patient to return the following week for a second visit and follow-up testing. Partner notification and contact tracing was discussed with the patient but she refused, stating “I don’t want to get him in trouble.” It was noted that during her follow-up visit which she chose to attend without her mother, the patient appeared to be calm and coping relatively well with her diagnosis and agreed to start antiretroviral therapy. Her viral load became undetectable two months after diagnosis with an increase in her CD4 count to 448 cells/mm3. However, during subsequent STI screening she tested positive twice for chlamydia and reported wanting to become pregnant “so that my boyfriend will never leave me.” She stated he was unwilling to come to clinic with her but he did accept EPT for chlamydia.

Case 1 demonstrates a few challenges inherent in the care of the adolescent patient with behaviorally acquired HIV. First, this young woman is in a high-risk group for HIV acquisition as a young African-American female, and likely acquired HIV from her condomless heterosexual encounter (the most common transmission category for women). Confidentiality and seeing the adolescent alone seemed to improve the tone of the visit and likely contributed to her adherence and consistent follow-up visits. In this way, her evolving autonomy was respected and she contributed to decision-making in her own care. However, the fact that she became reinfected with chlamydia twice while remaining adherent to her HIV regimen demonstrates a lack of understanding and insight regarding those high-risk behaviors associated with HIV acquisition in the first place, and certainly increased the risk of transmission to her partner. While she did not share many details about her relationship, and it is unclear whether or not she was in a position to negotiate condom use with her boyfriend, her self-efficacy may have been remarkably reduced in the setting of an unhealthy relationship. Lastly, her concern regarding pregnancy in order to remain with her boyfriend demonstrates some elements of the “myth of invulnerability” and the feeling of “wanting to belong” common to the adolescent age group. Regarding partner management, the patient expressed that the partner would accept EPT for Chlamydia. However, she did not want to involve her partner regarding HIV notification and contact tracing for fear of ramifications. As mentioned previously, anonymous partner notification and contact tracing are available through and supported by the public health system in many states. This was offered to the patient but unfortunately she did not accept even after emphasis on confidentiality, because she felt the partner “would know that I told on him.” It is not clear whether the relationship was of an abusive nature, as the patient refused to share further details about her boyfriend or about the relationship in general.

Case 2

An 18-year-old Latino male presented to the Pediatric Emergency Room with fever, malaise, and sore throat. During evaluation he disclosed to the ER resident that he had engaged in anal intercourse with an anonymous male partner in the past two weeks. The patient was screened for syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea including pharyngeal and rectal NAATs and HIV testing was sent. He was called back to the Pediatric Infectious Diseases clinic when rectal chlamydia testing and HIV testing were both positive. The patient was hesitant to come into the clinic visit and expressed that he knew testing was positive, but that he did not want to receive any treatment, and was ashamed of his sexuality. The patient did eventually come to clinic and was treated for rectal chlamydia and received counseling regarding his HIV diagnosis. After seeing the patient alone and reinforcing the fact that he had no viral resistance and was an excellent candidate for antiretroviral therapy, the patient agreed to start treatment and had an undetectable viral load within the next few months. He also requested that clinic staff be present and assist him with HIV diagnosis disclosure to his family, including his openly gay brother, although he was not yet comfortable disclosing his own sexuality. Four months after diagnosis he came to clinic with a complaint of a rash; he was noted to have erythematous lesions on his palms, soles, and scrotum. He had no neurologic findings on evaluation and was otherwise well. He also disclosed feeling very depressed about his diagnosis and that he had started to have anonymous sexual partners, all male, and had started using methamphetamine. The patient refused drug counseling or psychiatric support but remained in close touch with the pediatric social worker, with whom he developed a strong rapport. He was treated empirically for secondary syphilis at that visit. RPR titers were 1:64 and eventually declined to 1:2 one year after treatment, with no recurrence of symptoms or concern for reinfection. During clinic follow-ups he reported ceasing drug use and receiving support from his family regarding his sexuality, as he had finally decided to disclose to them and felt comfortable doing so on his own. Almost two years after diagnosis he still had an undetectable viral load, and had had negative STI screening since his syphilis diagnosis. He was referred to an adult infectious diseases practitioner for transition of care but continued to be seen in pediatric clinic for several visits until he became comfortable with the new care team. Since full transition 2.5 years after diagnosis, he continued to be seen regularly in follow-up and still had an undetectable viral load.

Case 2 shows another patient in one of the highest risk groups for both HIV and syphilis: a young Latino/Hispanic man who has sex with men (MSM). His mode of acquisition was also the most common for men acquiring HIV in the US. The patient had significant difficulty accepting his sexuality and wanted to be “normal,” showing the adolescent’s very common desire to “belong.” This patient had comorbidities common to youth that could have potentially impeded his care—drug use and depressive symptoms. It was not until treatment for his depression and response to treatment was demonstrated, and his move from a large city to a small town, that we were able to optimize his HIV care and compliance to the point where his viral load became undetectable. Similar to Case 1, it also demonstrates the patient’s lack of understanding and insight regarding those high-risk behaviors associated with HIV acquisition, as the patient developed secondary syphilis after his HIV diagnosis and also had evidence of mild developmental delay. In addition, even if adolescents have some understanding of potential risks, the perceived benefits of new sexual relationships typically outweigh them. However, in this case the patient was compliant with his treatment and follow-up and was able to transition successfully to adult care with significant support from his pediatric care team. As described previously, another important issue in this case is that of disclosure to others, and the clinician team offered support to the patient while he told his family about his diagnosis.

Conclusions

Youth constitute one of the highest risk groups for STI and HIV acquisition and transmission as well as unintended pregnancy and are in a unique period of psychosocial development. This creates a “perfect storm” particularly in HIV-positive youth for additional STI acquisition and transmission. Effective interventions for decreasing high-risk activity must include acknowledgement of normal adolescent development as inclusive of sexual exploration, skillful identification of motivational issues, and a clear and mature addressing of the pertinent issues, all using youth-oriented terminology and language relevant to the specific youth patient’s developmental stage [6]. Case-finding and screening for STIs among these youth are key, as coinfection with STIs remains common. Regardless of disease duration or mode of HIV transmission, every effort must be made to engage and retain HIV-infected youth and their partners in care and prevention, to improve and maintain long-term health, through and into their adult years.

References

Guttmacher Institute. Teenagers’ sexual and reproductive health: Developed countries. www.guttmacherinstitute.org/sections/sexandrelationships.php. Accessed 1 Feb 2016.

Panchaud C, Singh S, Reivelson D, Darroch JE. Sexually transmitted infections among adolescents in developed countries. Fam Plann Perspect. 2000;32(1):24–32.

Hazra R, Siberry GK, Mofenson LM. Growing up with HIV: children, adolescents, and young adults with perinatally acquired HIV infection. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:169–85.

CDC. HIV Surveillance in Adolescents and Young Adults (through 2014). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/slidesets/cdc-hiv-surveillance-adolescents-young-adults-2014.pdf. Accessed 7 March 2016.

Spear LP. Adolescent neurodevelopment. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(2 Suppl 2):S7–13.

Vermund SH, Wilson CM, Rogers AS, Partlow C, Moscicki AB. Sexually transmitted infections among HIV infected and HIV uninfected high-risk youth in the REACH study. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29S:49–56.

Carter MW, Kraft JM, Hatfield-Timajchy K, Snead MC, Ozeryansky L, Fasula AM, et al. The reproductive health behaviors of HIV-infected young women in the United States: a literature review. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2013;27:669–80.

Tassiopoulos K, Moscicki A-B, Mellins C, Kacanek D, Malee K, Hazra R, et al. Sexual risk behavior among youth with perinatal HIV infection in the United States: predictors and implications for intervention development. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;15:283–90.

Morris M, Goodreau S, Moody J. Sexual networks, concurrency, and STI/HIV. In: Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Stamm WE, Piot P, Wasserheit JN, Corey L et al., editors. Sexually transmitted infections, 4th ed. New York, McGraw Hill Medical; 2008, p 109–125.

Jennings JM, Ellen JM, Deeds BG, Harris DR, Muenz LR, Barnes W, et al. Youth living with HIV and partner-specific risk for the secondary transmission of HIV. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:439–44.

Brogly SB, Watts H, Ylitalo N, Franco EL, Seage GR 3rd, Oleske J, et al. Reproductive health of adolescent girls perinatally infected with HIV. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1047–52.

Moscicki A-B, Puga A, Farhat S, Ma Y. Human papillomavirus infections in nonsexually active perinatally HIV infected children. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2014;28:66–70.

Trent M, Chung S, Clum G. Adolescent HIV/AIDS trials network. New sexually transmitted infections among adolescent girls infected with HIV. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83:468–9.

Mullins TLK, Rudy BJ, Wilson CM, Sucharew H, Kahn JA. Incidence of sexually transmitted infections in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected adolescents in the United States. Int J STD AIDS. 2013;24:123–7.

Moscicki A-B, Ellenberg JH, Vermund SH, Holland CA, Darragh T, Crowley-Nowick PA, et al. Prevalence of and risks for cervical human papillomavirus infection and squamous intraepithelial lesions in adolescent girls. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:127–34.

Moscicki A-B, Ellenberg JH, Farhat S, Xu J. Persistence of human papillomavirus infection in HIV-infected and–uninfected adolescent girls: risk factors and differences, by phylogenetic type. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:37–45.

Shrestha S, Sudenga SL, Smith JS, Bachmann LH, Wilson CM, Kempf MC. The impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy on prevalence and incidence of cervical human papillomavirus infections in HIV-positive adolescents. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:295.

Moscicki A-B, Durako SJ, Houser J, Ma Y, Murphy DA, Darragh TM, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and abnormal cytology of the anus in HIV-infected and uninfected adolescents. AIDS. 2003;17:311–20.

Mullins TLK, Wilson CM, Rudy BJ, Sucharew H, Kahn JA. Incident anal human papillomavirus and human papillomavirus-related sequelae in HIV-infected versus HIV-uninfected adolescents in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40:715–20.

Holland CA, Ma Y, Moscicki A-B, Durako SJ, Levin L, Wilson CM. Seroprevalence and risk factors of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human cytomegalovirus among HIV-infected and high-risk uninfected adolescents: findings of the REACH study. Sex Transm Dis. 2000;27:296–303.

Padian NS, Shiboski SC, Jewell NP. Female-to-male transmission of human immunodeficiency virus. JAMA. 1991;266:1664–7.

Wofsy CB, Cohen JB, Hauer LB, Padian NS, Michaelis BA, Evans LA, Levy JA. Isolation of AIDS-associated retrovirus from genital secretions of women with antibodies to the virus. Lancet. 1986;1:527–9.

Berman SM, Ellen JM. Adolescents and STIs Including HIV Infection. In: Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Stamm WE, Piot P, Wasserheit JN, Corey L et al., editors. Sexually transmitted infections, 4th ed. New York: McGraw Hill Medical; 2008, p 165–185.

Jacobson DL, Peralta L, Farmer M, Graham NM, Gaydos C, Zenilman J. Relationship of hormonal contraception and cervical ectopy as measured by computerized planimetry to chlamydial infection in adolescents. Sex Transm Dis. 2000;27:313–9.

Morrison CS, Bright P, Wong EL, Kwok C, Yacobson I, Gaydos CA, et al. Hormonal contraceptive use, cervical ectopy, and the acquisition of cervical infections. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31(9):561–7.

Lee V, Tobin JM, Foley E. Relationship of cervical ectopy to chlamydia infection in young women. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2006;32:104–6.

Sparling PF. Biology of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. In: Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Stamm WE, Piot P, Wasserheit JN, Corey L et al., editors. Sexually transmitted infections, 4th ed. New York: McGraw Hill Medical; 2008, p 608–626.

Henry-Reid LM, Martinez J. Care of the adolescent with HIV. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51(2):319–28.

Plourde PJ, Pepin J, Agoki E, Ronald AR, Ombette J, Tyndall M, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 seroconversion in women with genital ulcers. J Infect Dis. 1994;170(2):313–7.

Moss GB, Clemetson D, D’Costa L, Plummer FA, Ndinya-Achola JO, Reilly M, et al. Association of cervical ectopy with heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus: results of a study of couples in Nairobi, Kenya. J Infect Dis. 1991;164(3):588–91.

Kleppa E, Holmen SD, Lillebo K, Kjetland EF, Gundersen SG, Taylor M, et al. Cervical ectopy: associations with sexually transmitted infections and HIV. A cross-sectional study of high school students in rural South Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2015;91:124–9.

Moscicki AB, Ma Y, Holland C, Vermund SH. Cervical ectopy in adolescent girls with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2001;183(6):865–70.

Crowley-Nowick PA, Ellenberg JH, Vermund SH, Douglas SD, Holland CA, Moscicki AB. Cytokine profile in genital tract secretions from female adolescents: impact of human immunodeficiency virus, human papillomavirus, and other sexually transmitted pathogens. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(3):939–45.

Sill AM, Kreisel K, Deeds BG, Wilson CM, Constantine NT, Peralta L, et al. Calibration and validation of an oral fluid-based sensitive/less-sensitive assay to distinguish recent from established HIV-1 infections. J Clin Lab Anal. 2006;21:40–5.

Pham T, Belzer M, Church JA, Kitchen C, Wilson CM, Douglas SD, et al. Assessment of thymic activity in human immunodeficiency virus-negative and—positive adolescents by real-time PCR quantitation of T-cell receptor rearrangement excision circles. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2003;10(2):323–8.

Douek DC, McFarland RD, Keiser PH, Gage EA, Massey JM, Haynes BF, et al. Changes in thymic function with age and during the treatment of HIV infect. Nature. 1998;396(6712):690–5.

Jamieson BD, Douek DC, Killian S, Hultin LE, Scripture-Adams DD, Giorgi JV, et al. Generation of functional thymocytes in the human adult. Immunity. 1999;10(5):569–75.

Flynn PM, Rudy BJ, Lindsey JC, Douglas SD, Lathey J, Spector SA, et al. Long-term observation of adolescents initiating HAART therpy: three-year follow-up. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007;23(10):1208–14.

Flynn PM, Rudy BJ, Douglas SD, Lathey J, Spector SA, Martinez J, et al. Virologic and immunologic outcomes after 24 weeks in HIV type 1-infected adolescents receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2004;190(2):271–9.

Kinsman S, Romer D, Furstenberg FF, Schwarz DF. Early sexual initiation: the role of peer norms. Pediatrics. 1998;102:1182–92.

Upadhyay UD, Hindin MJ. Do perceptions of friends’ behaviors affect age at first sex? Evidence from Cebu, Philippines. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:570–7.

Lyketsos CG, Treisman GJ. Mood disorders in HIV infection. Psychiatr Ann. 2001;31(1):45–9.

Pence BW, Miller WC, Whetten K, Eron JJ, Gaynes BN. Prevalence of DSM-IV-defined mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders in an HIV clinic in the southeastern United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Synd. 2006;42(3):298–306.

Conner LC, Wiener J, Lewis JV, Phill R, Peralta L, Chandwani S, Koenig LJ. Prevalence and predictors of drug use among adolescents with HIV infection acquired perinatally or later in life. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:976–86.

Centers for Disease Control and prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2013. MMWR; 2014, 63(SS-4).

Bearman BS, Moody J, Stovel K. Chains of affection: the structure of adolescent romantic and sexual networks. Am J Sociol. 2004;110:9144–11.

Watts CH, May RM. The influence of concurrent partnerships on the dynamics of HIV/AIDS. Math Biosci. 1992;108:89–104.

Hudson C. Concurrent partnerships could cause AIDS epidemics. Int STI AIDS. 1993;4:349–53.

Morris M, Kretzschmar M. Measuring concurrency. Connections. 1994;17(1):31–4.

Moody J. The importance of relationship timing for diffusion. Soc Forces. 2002;81(1):25–56.

Amaro H. Love, sex, and power: considering women’s realities in HIV prevention. Am Psychol. 1995;50:437–47.

Harper GW. Contextual factors that perpetuate statutory rape: the influence of gender roles, sexual socialization, and sociocultural factors. DePaul Law Rev. 2001;50:301–22.

Morris M, Zavisca J, Dean L. Social and sexual networks—their role in the spread of HIV/AIDS among young gay men. AIDS Educ Prev. 1995;7(5):24–35.

Service S, Blower S. HIV transmission in sexual networks: an empirical analysis. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1995;260(1359):237–44.

Aberg JA, Gallant JE, Ghanem KG, Emmanuel P, Zingman BS, Horberg MA. Primary care guidelines for the management of persons infected with HIV: 2013 update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(1):1–10.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(3):1–138.

Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adult_oi.pdf.

Kim DK, Bridges CB, Harriman KH. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), ACIP adult immunization work group. Advisory committee on immunization practices recommended immunization schedule for adults Aged 19 Years or Older—United States, 2016. MMWR, 2016; 65(4):88–90.

Robinson CL, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), ACIP Child/adolescent immunization work group. Advisory committee on immunization practices recommended immunization schedules for persons aged 0 through 18 Years—United States, 2016. MMWR; 2016; 65(4):86–87.

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Disease Society of America. Recommendations for testing, managing and treating Hepatitis C. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed 11 March 2016.

Papp JR, Schachter J, Gaydos CA, Van Der Pol B. Recommendations for the laboratory-based detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae—2014. MMWR. 2014;63(2):1–17.

Schachter J, Chernesky MA, Willis DE, Fine PM, Martin DH, Fuller D, et al. Vaginal swabs are the specimens of choice when screening for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: results from a multicenter evaluation of the APTIMA assays for both infections. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:725–8.

Michel CC, Sonnex C, Carne CA, White JA, Magbanua JP, Nadala EC Jr, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis load at matched anatomical sites: implications for screening strategies. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1395–402.

Falk L, Coble BI, Mjörnberg PA, Fredlund H. Sampling for Chlamydia trachomatis infection—a comparison of vaginal, first-catch urine, combined vaginal and first-catch urine and endocervical sampling. Int J STI AIDS. 2010;21:283–7.

Masek BJ, Arora N, Quinn N, Aumakhan B, Holden J, Hardick A, et al. Performance of three nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae by use of self-collected vaginal swabs obtained via n Internet-based screening program. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1663–7.

Shafer MA, Moncada J, Boyer CB, Betsinger K, Flinn SD, Schachter J. Comparing first-void urine specimens, self-collected vaginal swabs, and endocervical specimens to detect Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae by a nucleic acid amplification test. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:4395–9.

Schachter J, McCormack WM, Chernesky MA, Martin DH, Van Der Pol B, Rice PA, et al. Vaginal swabs are appropriate specimens for diagnosis of genital tract infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:3784–9.

Hsieh YH, Howell MR, Gaydos JC, McKee KT Jr, Quinn TC, Gaydos CA. Preference among female army recruits for use of self-administered vaginal swabs or urine to screen for Chlamydia trachomatis genital infections. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:769–73.

Klinger EV, Kapiga SH, Sam NE, Aboud S, Chen CY, Ballard RV, et al. A community-based study of risk factors for Trichomonas vaginalis infection among women and their male partners in Moshi urban district, northern Tanzania. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:712–8.

McClelland RS, Sangare L, Hassan WM, Lavreys L, Mandaliya K, Kiarie J, et al. Infection with Trichomonas vaginalis increases the risk of HIV-1 acquisition. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:698–702.

Kissinger P, Amedee A, Clark RA, Dumestre J, Theall KP, Myers L, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis treatment reduces vaginal HIV-1 shedding. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:11–6.

Anderson BL, Firnhaber C, Liu T, Swarts A, Siminya M, Ingersoll J, et al. Effect of trichomoniasis therapy on genital HIV viral burden among African women. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39:638–42.

Tilson EC, Sanchez V, Ford CL, Smurzynski M, Leone PA, Fox KK et al. Barriers to asymptomatic screening and other STD services for adolescents and young adults: focus group discussions, 2004. BMC Public Health 2004; (4)21.

Boonstra H, Nash E. Minors and the right to consent to health care. Issues Brief (Alan Guttmacher Institute). 2000;2:1–6.

Skelton JR, Matthews PM. Teaching sexual history taking to health care professionals in primary care. Med Educ. 2001;35(6):603–8.

Shindel AW, Ando KA, Nelson CJ, Breyer BN, Lue TF, Smith JF. Medical student sexuality: how sexual experience and sexuality training impact US and Canadian medical students’ comfort in dealing with patients’ sexuality in clinical practice. Acad Med. 2010;85(8):1321–30.

Boekeloo BO, Schamus LA, Cheng TL, Simmens SJ. Young adolescents’ comfort with discussion about sexual problems with their physician. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150(11):1146–52.

Marcell AV, Bell DL, Lindberg LD, Takruri A. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infection/human immunodeficiency virus counseling services received by teen males, 1995–2002. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(6):553–9.

Burstein GR, Lowry R, Klein JD, Santelli JS. Missed opportunities for sexually transmitted diseases, human immunodeficiency virus, and pregnancy prevention services during adolescent health supervision visits. Pediatrics. 2003; 111(5, pt 1):996–1001.

Alexander SC, Fortenberry JD, Pollak KI, Bravender T, Davis JK, Østbye T, et al. Sexuality talk during adolescent health maintenance visits. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(2):163–9.

Blank LJ, Rompalo AM, Erbelding EJ, Zenilman JM, Ghanem KG. Treatment of syphilis in HIV-infected subjects: a systematic review of the literature. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87:9–16.

Moran JS, Levine WC. Drugs of choice for the treatment of uncomplicated gonococcal infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20(Suppl 1):S47–65.

Newman LM, Moran JS, Workowski KA. Update on the management of gonorrhea in adults in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 3):S84–101.

Bernstein KT, Stephens SC, Barry PM, Kohn R, Philip SS, Liska S, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae transmission from the oropharynx to the urethra among men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1793–7.