Abstract

Value instantiations—exemplifiers of an abstract or general category—are a new issue in human value research. Experiments have recently highlighted the important role of value instantiations in bridging the gap between abstract values and specific actions. In this chapter, we describe the general role of category instantiations in psychology, drawing on relevant literature in cognitive and social psychology. We discuss the relevance of value instantiations to important topics in the study of values, such as (non-)differences in values between nations, and the application of values to behavior. We then discuss instantiations as a mechanism through which values are related to behavior. We demonstrate that instantiations moderate the relationship between values and behavior: If the measured behaviors reflect typical instantiations of a value, the relationship between the two is stronger. Finally, we illustrate the potential roles of value instantiations by describing a method for measuring them and then examining findings relevant to two values: protecting the environment and family security.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

As described in this volume, abundant research has taught us a great deal about links between values and behavior. At the same time, however, one important puzzle remains unaddressed: When people arrive at a situation and have to decide how to act, how do they decide which values should guide their actions? In this chapter, we propose a model to explain this process.

The model we propose introduces value instantiations and suggests that they play a critical role in explaining the effects of values on behavior. That is, we propose that previous experiences and the context influence which behaviors are considered as prominent instantiations (examples) of a value, thereby determining which values guide action in the context. For example, the security of one’s own family is considered to be important across the world (Schwartz and Bardi 2001). Most of us are eager to protect close relatives and to provide them with a good life. But what does protecting close relatives mean, which relatives are close, in which way are they close (emotionally, physically), and how exactly are close relatives to be supported and protected?

The specific ways in which we imagine family security may vary across cultures. In countries such as Brazil, family security pertaining to children may have a large safety component because thousands of people are shot dead every year. In countries such as the UK, family security pertaining to children may have a large social component, because of large differences in the cost and quality of schools. Although empirical evidence indicates that family security is considered to be an important value across countries (Schwartz and Bardi 2001), different actions promote family security in each location. This example helps to illustrate how our mental representations of values matter. Even if the same level of importance is attributed to a value, different people may produce different concrete instantiations for a specific value.

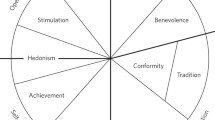

Our model of this process is depicted in Fig. 8.1. Personal experiences and social context influence the extent a behavior is seen as an instantiation of a value or set of values, which in turn determines the values that are activated in the context, and their relative importance then influences behavior. This pathway occurs alongside other independent influences not shown here, such as influences of social norms and control over behavior performance.

In this chapter, we first discuss general theory and evidence regarding the role of instantiation in conceptual categories, including evidence from cognitive and then social psychology. While cognitive and social psychology has shown some awareness of the importance of instantiations, their role has been underappreciated in the context of understanding values and value-guided behavior. This chapter will therefore turn to describing how and why consideration of value instantiations helps to understand past evidence and the role of value instantiations in bridging the gap between values and behavior. Finally, we describe a method for directly examining value instantiations and illustrate its utility by comparing value instantiations between two countries.

The Cognitive Psychology of Instantiations

Before explaining further why we consider instantiations of human values to be important, it is necessary to define instantiations and understand their role for general categories. Instantiating a rule or concept is its application to a concrete exemplar. “Instantiation” thus refers to a particular realization or instance of an abstraction or to the process of producing such an instance. Instantiation is consequently based on the relationship between general and specific, such as different levels in a conceptual hierarchy. Thus, football is an instantiation of the category sport, red is an instantiation of color, and sunscreen is an instantiation of the things to take to the beach.

It is a fundamental insight within cognitive psychology that levels in conceptual hierarchies such as “animal”-“dog”-“Doberman” are not psychologically equivalent (see, e.g., Rosch et al. 1976a). Specifically, the intermediate level (‘dog’) seems privileged in many cognitive contexts (such as concept acquisition or the likelihood or speed of naming), and empirical research has sought to determine exactly why that is (e.g., Rogers and Patterson 2007). At the same time, members of a category within a level are generally not equivalent. Instead, they vary in typicality, that is, the extent to which they are a good example (e.g., Rosch 1973; Rosch et al. 1976b). For instance, a robin might be considered to be a good (typical) example for the category bird, but a penguin may not.

All instances of a category within a level can be placed on a continuum of category representativeness named graded structure (Barsalou 1985). It starts with the most representative or most typical member and progresses to less typical members, and category boundaries (the boundary between members and non-members) are typically “fuzzy” (e.g., McCloskey and Glucksberg 1978). Fuzzy borderlines are prevalent in natural language categories (“cup,” “democracy,” etc.) and cognitive concepts such as human values. In general, the more fuzzy the borderline, the more instantiations are possible.

This “graded structure” of natural language categories appears to be a critical and universal property of categories and the process of categorization. Graded structure can predict performance on acquisition, exemplar production, and category verification (Barsalou 1985). That is, the location of the exemplar on the graded structure continuum can predict the ease with which it is learnt, produced, or verified as a member of the category. The most typical members tend to facilitate these processes (e.g., see Rosch 1973).

The most important determinants of graded structure are central tendency, ideals, and familiarity (Barsalou 1985, 1987). Central tendency refers to any kind of information based on average, median, or modal values of category instances. In contrast, ideals simply reflect characteristics that exemplars should have and therefore do not depend on actual existing exemplars (the “ideal democracy” might, for example, not actually exist). Finally, familiarity depends on how often a specific instance can be found across contexts; thus, familiarity is related to the frequency and intensity of how the exemplars are experienced or observed.

Graded structure has a broad influence on the acquisition of categories. Rosch (1973) carried out two studies with a sample of Dani participants in New Guinea, because their language does not have terms for basic colors. Thus, participants were completely new to the categories to be learned. Fictitious names, based on words in Dani language, were assigned to different colors and shapes. Rosch demonstrated that the names for natural prototypes of colors and shapes are learned faster than peripheral or “distorted” exemplars. For instance, the presumed natural prototype for color was represented by eight focal colors, and the remaining set of colors had a roughly longer or shorter wavelength in hue. The names of the natural prototypes (focal colors) were learned to criterion with fewer errors than the non-focal colors. Rosch also found that these prototypes may be identified by individuals as the defining, typical instances of a concept, enabling them to serve as cognitive reference points (Rosch 1975).

Subsequent evidence found that category graded structure can change depending on the specific context (Roth and Shoben 1983). For example, if the category animal is processed in the context of riding, horse and mule are more typical than cow and goat. However, if the context shifts to milking, then cow and goat are more typical. So there is a strong effect of context in instantiation.

Typicality effects are found even with concepts that have strict definitions, such as “odd number” or “even number” (Armstrong et al. 1983), suggesting they are pervasive in the human conceptual system. Furthermore, research suggests that they affect both concrete and abstract concepts. Concerning the latter, Hampton (1981) gave participants a list of eight abstract concepts (e.g., “a work of art, “a fair decision”) and either asked them to list attributes of the concepts or to give examples of the concept. For instance, participants described “a work of art” as being “visual,” “man-made,” “pleasing,” while using examples such as the “Mona Lisa,” “A red painting,” or “Covent Garden market.” Hampton then had judges code the extent to which each example was a good instance of the concept (i.e., from “good examples,” “atypical,” “related non-example,” to “unrelated non-example”). A subsequent group of participants then received a subset of examples that varied in their fit to the concept (equally from “good” to “unrelated”), and they were asked to rate the extent to which each example possessed one of 12–16 of the features that had been previously identified as being potential attributes of the concept. Results indicated that the better examples had a higher number of the attributes of the concept, particularly for five of the abstract concepts (work of art, science, crime, a kind of work, and a just decision), though the degree of variation in typicality varied.

Categorization in Social Attitudes and Behavior

There is evidence for the importance of the role of graded structure in social attitudes and behavior. For instance, in a study conducted by Lord et al. (1984), they observed that participants with favorable attitudes toward a university’s social group were willing to interact with a prototypical target person to a greater extent than with a target person presenting only half of the attributes considered typical for members of that group. Participants in this research completed measures of their attitudes toward members of two eating clubs (of which the participants were not members themselves) and evaluated which attributes they considered typical for the members, and how much they liked them or were willing to interact with them. Approximately 3 months later, without mentioning the first part of the study, participants were asked to choose one student to work with on a project. They received descriptions of two students; each was identified as a member of one of the two eating clubs, with one member described using traits that were 100% typical according to the participant’s own prior descriptions, and the other 50% typical. The authors observed greater consistency between attitudes and behavior when participants were confronted with a target person whose attributes were previously judged as typical for the members of that eating club. That is, participants who reported more positive attitudes toward members of the eating club were more likely to choose to work with the typical member than participants with less positive attitudes, but this relation was weaker when the member was described with only half of the typical attributes. Lord et al. (1984) replicated these findings in a study of attitudes toward a different target group, gay men. Thus, across two real social groups, attitudes were better predictors of behavior toward typical members of the groups than of atypical members of the groups.

A different set of studies points in a similar direction, but instead of using known social groups, the researchers investigated the role of experience that participants had with the target. Lord et al. (1991) found that the correlation between attitudes and behavior was more dependent on typicality when participants were less experienced and skilled regarding the social category. For instance, in one experiment, the researchers assessed attitudes to people with mental illness and examined willingness to interact with a target presenting signs of mental illness, either through typical or atypical characteristics. Students who knew or had prior contact with people who have mental illness displayed higher attitude–willingness consistency regardless of the typicality of the character. In contrast, students with relatively little prior knowledge or contact exhibited attitude–behavior consistency when the target individual was prototypical of people with mental illness than when the individual was atypical. Thus, the perceived typicality of a target affected the relationship between attitudes and behavior for participants who had less skills or experience with the category.

Subsequent research found that individuals apply social policy attitudes more consistently toward typical than atypical persons affected by the policy (Lord et al. 1994). For example, participants in favor of the death penalty tended to apply their opinions of the acceptability of the death penalty for a fictitious criminal only when the character was described with typical characteristics of murderers (e.g., impulsive), but not with atypical characteristics of murderers (e.g., not fearful, not domineering). However, participants who were against the death penalty were consistent with their attitudes, regardless of the presented character. Drawing from this pattern and similar mixed results in another study, Lord et al. (1994) suggested that social policy attitudes may invoke principles and contexts that lead to asymmetries and boundaries in the extent to which typicality moderates the connection between social policy and attitudes and other judgments.

Together, the evidence reviewed in this section illustrates the importance of knowing about the instantiations that are contained within people’s mental representations of concepts. Some (typical) instantiations may be processed more easily, used as reference points, and contain more features belonging to a concept. In social contexts, this can lead to greater effects of attitudes toward a category on relevant judgments and behavior when people are considering typical instances of the category than when considering atypical instances. At the same time, however, the research on social category attitudes shows that the role of instantiations may be complex. In this context, the role of instantiations is influenced by attitude strength (i.e., high experience, knowledge) and attitude topic (e.g., death penalty, welfare).

Instantiations of Human Values

In this section, we describe how the above outline concept of instantiation applies to human values, and address some boundary conditions. Human values have, as any abstract concept, instantiations. One element of the graded structure, ideals, is especially important to goal-directed categories such as values. Ideals are the characteristics that exemplars should have to serve a certain goal; they tend to be an extreme representation and may never be reached (e.g., what does a perfect equal or free world look like?). The other two elements of graded structure, central tendency and familiarity, are also relevant to values, although it may be harder to spontaneously think about value instantiations in terms of them. Central tendency refers to the “average” properties of a given category, so they depend directly on the exemplars of that category, especially those that the person has experienced. Familiarity refers to how often the person has experienced certain instances across situations.

Politeness, for example, is a conformity value that is about courtesy and good manners. Being “respectful” could be seen as (part) of the central tendency because it is a highly probable property of situations that require politeness (esp. formal encounters), and what exactly counts as “respectful” (as opposed to obsequious, for example) will be determined by the range and distribution of relevant instances. “Saying hello’ is a very familiar instantiation. Finally, not bothering people at any time could represent the ideal element because it is an extreme representation that may never be reached. Although this suggested example is speculative and may vary across cultures, it serves to illustrate the range of properties value instantiations might possess. An interesting and important exercise is to map value instantiations as a means of determining which examples serve different roles (e.g., as central tendency vs. familiar example), while documenting how these roles affect the psychological processes that encompass values. We return to this issue later in the chapter.

Another interesting issue is that values per se may differ in levels of abstraction. For instance, in Schwartz’s (1992) model, protecting the environment might be perceived as a more concrete value than world of beauty, because protection of the environment implicitly circumscribes a restricted range of actions. It is conceivable that typical instantiations are more difficult to obtain for the values that are higher in abstraction. However, this does not mean that more abstract values have no instantiations, as this would be tantamount to saying that abstract values have no applicability to real-world situations and play no role in practice. The idea that abstraction is a reason for some variation in the number of available and accessible instantiations per value seems plausible to the extent that, all other things being equal, greater abstraction means greater scope, that is, more things a value could apply to. The question, however, is the extent to which the “all other things being equal” really applies in the values domain: It seems entirely possible that there are very abstract values that are drawn on infrequently, and that there are more specific values, which cover fewer distinct types of instances, that occur extremely often. In other words, abstraction may be a factor that gives rise to differences in typicality, but in all likelihood, the relationship between abstraction and typicality is not a simple, direct, one. We are not aware of any available method to assess level of abstraction precisely, making this an interesting question for future research.

Studying instantiations of values is particularly challenging because values have both a cognitive and a motivational aspect (e.g., Schwartz 1992). In contrast, the process of instantiation is, in the first instance, a cognitive one. However, we also propose that motivation matters to the process of instantiation. For example, people may be more willing to find an appropriate instantiation of a value in a context where the value is of greater importance and relevance to the situation. For instance, a person who cherishes protection of the environment may exert a lot of effort to decide which food choices are most environmentally sustainable in a new restaurant where the food options are unusual and unknown.

How Instantiations Help to Explain Past Evidence

Why do we consider instantiations of human values to be an important part in human value research, especially for bridging the gap between values and behavior? The importance of instantiation is twofold: methodological and theoretical. We start with methodological considerations. Following the example given at the beginning of this chapter, imagine, for example, a researcher who wants to investigate the relationship between the value of family security and behavior. Which behaviors should the researcher examine? As we saw in the example above, in an unstable and unsafe country, it may make sense to measure the amount of CCTVs on one’s property, the “quality” of the fence (e.g., electric or barb wire), or access to a safe car for taking children to school. In a safe and stable country, it may make more sense to estimate the amount of financial support within a family, family stability, and harmony in family relationships instead. Consequently, a researcher who looks at the use of home security measures in a relatively safe and stable country might discover little connection to the extent to which the individuals’ value family security, because the individuals mentally represent the value in a very different way. Without knowing the concrete instantiations that are most relevant to people’s values, the strength of the relations between values and behavior might be underestimated.

To assess the relationships of values to behavior, it is necessary to take into account the extent to which the behavior is typical of any targeted values within a specific social context. An example of this approach occurred in research by Bardi and Schwartz (2003). They asked participants to generate behaviors that express each of the ten value types. Bardi and Schwartz found correlations between values and behavior that were higher than in studies where the behavior was chosen out of theoretical considerations, including studies of organizational citizenship behavior (OCB, Arthaud-Day et al. 2012) and intentions to support social action (Feather et al. 2012). Furthermore, studies have found lower correlations when they have employed a behavior measure developed in a different country. For example, Pozzebon and Ashton (2009) used Bardi and Schwartz’s (2003) measure, which was developed in Israel and in Canada. Pozzebon and Ashton found somewhat lower correlation coefficients than had been obtained by Bardi and Schwartz. Although this trend could be attributable to diverse factors (e.g., sample characteristics, respondent conscientiousness), one possibility is that the behaviors assessed by Bardi and Schwartz were less typical of the values in the Canadian population than in the Israeli one.

Given the evidence for the typicality effect in social attitudes and behavior (Lord et al. 1994), a value is likely to predict only weakly behaviors that are not considered to be typical of that value (see Maio et al. 2009). For example, although it was postulated and found that specific value types like benevolence or achievement correlate with OCB (Arthaud-Day et al. 2012), there are other behaviors that are considered to be more typical of these values (see Bardi and Schwartz 2003, for examples). In other words, many participants would likely agree that OCB is related to benevolence, but would not come up with this example by themselves. The lack of a spontaneous association between the value and OCB should weaken the extent to which the value predicts this behavior, because the value may not be automatically activated when this behavior is contemplated (see Maio 2010). In other words, the strength of the correlation between a value and a behavior is likely to be moderated by the typicality of the behavior for the respective value: Value–behavior relations should be larger if the behavior that is measured is considered more typical for the specific value. This may help to understand the role of value instantiations in bridging the gap between values and behavior, especially for cross-cultural research.

The way in which instantiations bridge the gap between values and behavior is further illustrated in a research project that examined the effect of value salience on pro-environmental behavior (Evans et al. 2013). In two studies, the investigators manipulated the salience of different reasons for a pro-environmental behavior (car-sharing), emphasizing either a self-enhancing value orientation (i.e., save money) or a self-transcending value orientation (i.e., save the environment). Results indicated that the salience of the self-transcending value orientation (but not the self-enhancing value orientation) caused a spillover effect toward another pro-environmental behavior, namely recycling. As described later in this chapter, recycling is a typical example of pro-environmental behavior in the UK, where this study of reasons priming took place. Two other behaviors were measured: choosing scrap over new paper and choosing an energy-saving mode while using a computer. These behaviors are atypical examples of pro-environmental behavior in the UK. In the analyses of British participants’ instantiations of protecting the environment described below, choosing an energy-saving mode on a computer and using scrap paper were not mentioned. These behaviors are not as strongly connected in memory to the value of protecting the environment. For these atypical behaviors, no significant effect of value salience was found. In sum, we found that raising the salience of a value had an effect on endorsement of behaviors that are consistent with that value, but the effect was limited to behaviors that are typical instantiations of that value. These results are in line with findings from social categorizations as described above (Lord et al. 1991).

This example illustrates the theoretical importance of considering value instantiation. Specifically, it is an inherent quality of basic values that they are abstract. This means that any application of such values needs to “bridge the gap” between the abstract level of the value and the specific situation or instance to which it is to be applied. This is fundamental to how values “work.” The abstract nature of values enables widespread agreement about values themselves, while allowing for strong disagreement in actual practice. For example, the term “human dignity” is often used in international agreements like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, because everyone can agree that this concept is important. However, different parties “can conceive human dignity as representing their particular set of values and worldview” (Shultziner 2003, p. 5), which is one reason why there are many differences across the world in how humans are treated by their governments. On an abstract level, human values barely differ between countries. Differences between nations explain on average only 2–12% of the variance between individuals (Fischer and Schwartz 2011). That is, the variance in values is much larger within than between countries. The differences between countries may therefore be much less about how they are regarded in the abstract than about how the values are exemplified (i.e., instantiated) in different cultures.

One important example pertains to the value equality. In many countries, women are still considered as unequal to men, and they are granted less in terms of rights and opportunities. People in these countries may attribute high important to treating all men equally and to treating all women equally, but may not apply egalitarian notions to the treatment of men as compared to the treatment of women, or may instantiate equality between men and women in a different way (e.g., according to perceived differences in needs, abilities, duties). If two cultures do not instantiate equality relating to men and women in the same way, then there may be strong differences in the treatment of men and women even when equality is viewed as highly important.

To illustrate this effect, we use data from the fourth round of the European Social Survey (www.europeansocialsurvey.org). This survey includes over 56,700 people from 31 countries who have responded to a variety of questions, including items from a short version of the Portrait Value Questionnaire (PVQ, Schwartz et al. 2001). One item assessed equality (“Important that people are treated equally and have equal opportunities”) and was answered on a 6-point Likert scale (1 “very much” to 6 “not at all”).

Participants from Turkey (n = 2416), a country that has been found to discriminate women on average more than other European countries (Tansel et al. 2014), agreed with the item virtually to the same extent as participants in the other European countries (M = 2.06, SD = 0.93 for Turkey; M = 2.10, SD = 1.06 for the 30 remaining countries; Cohen’s d = 0.05). However, a comparison of the means of two items that explicitly asked about gender discrimination revealed more unequal attitudes within the Turkish sample. Specifically, using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (agree strongly) to 5 (disagree strongly), participants rated their agreement with the statements, “A woman should be prepared to cut down on her paid work for the sake of her family” and “When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women.” Turkish participants agreed with the first (M = 2.14, SD = 0.92) and second (M = 2.20, SD = 1.13) statements much more than participants in the 30 other countries (M = 2.86, SD = 1.18, d = 0.77, and M = 3.61, SD = 1.23, d = 1.24, respectively). Interestingly, the equality item was only weakly correlated with the two items about gender discrimination, in both Turkey (r[2225] = 0.11 and r[2251] = 0.13, ps < 0.001) and the rest of Europe (r[52,007] = −0.01, p = 0.047 and r[51,659] = −0.06, p < 0.001). Although weak, the correlations in Turkey were positive, indicating that those Turkish participants who endorse equality more were more in favor of discriminating women. In the 30 European countries, the correlations were small, but reliable in the opposite direction, further supporting the claim that gender discrimination is an instantiation of the equality values in Europe in general, but not in Turkey. This short analysis demonstrates that the instantiation of gender discrimination as being part of the value of equality differs between countries, both in terms of mean differences and correlations, even when the value of equality per se is held at the same level of importance.

The examples of instantiation we have discussed make clear that one cannot understand how values guide behavior without understanding how the process of instantiation takes place. Bridging the gap between abstract and specific, that is, both recognizing that a specific situation falls under a general value (or more likely several values) and working out the implications of this for action, is a complex cognitive task. Without understanding how people manage this task, we will neither fully understand the role of values in human behavior, nor be able to effectively change behaviors where this is desired.

For example, it makes little sense to try to tackle issues of gender equality by emphasizing equality per se in a place that sees little or no connection between gender equality and equality as a value. Similarly, it would not make sense to aim for less CO2 emissions from poor house insulation by emphasizing the importance of environment protection in a place that sees no connection between protecting the environment and these emissions. Such attempts become feasible only when the value instantiations are brought into people’s conceptualization of the value itself, through cultural change, information campaigns, education, or other means. For such attempts to be successful, a more detailed understanding of the process of instantiation is required. Given that this process has largely been overlooked in past research, there is a considerable need for future studies that manipulate value instantiations, that examine the factors that make it easy or hard for instances to be recognized as instances of a value, and that examine the effects of changes in value instantiation on value–behavior relations over time.

A Methodology for Examining Instantiations and Human Values

Studying the instantiations of human values necessitates the development of a methodology that takes into account the distinctive characteristics of values. We describe here in detail a measure we developed for a cross-cultural study, which allowed us to examine the effects of the social context along with the effects of typicality.

In 2014, we compared students from Joao Pessoa, Brazil, with students from Cardiff, United Kingdom (UK). Cardiff is a typical city in the UK or even typical for “Western” countries with regard to income and safety. Joao Pessoa, however, is considered to be one of the most dangerous cities in the world. There, more than 67 times as many people are murdered compared to the UK per 100,000 inhabitants (Office for national statistics 2014; Statista 2014), creating a heightened fear of violence (Monteiro 2012). This results in more gated communities, high walls with electric fences around the houses, and fewer people walking outside in many neighborhoods, especially after sunset.

It is informative to consider the role of these differences with regard to two values in Schwartz’s (1992) model: protection of the environment and family security. The differences in violent crime suggest that the instantiations for the value family security may be quite different between inhabitants of Joao Pessoa, Brazil, and Cardiff, UK. Another difference between the two countries is that the UK focuses more heavily on protecting the environment through behaviors that reduce carbon emissions (e.g., solar panels, use of public transport), whereas Brazilians may focus more on the reduction of litter. (To our casual inspection, the streets in Joao Pessoa are, if anything, cleaner than in Cardiff.)

To explore instantiations of these values in both places, we asked 61 mostly postgraduate students from Joao Pessoa and 60 psychology undergraduate students or members of Cardiff University (students or staff from all disciplines) to take part in a survey of value instantiations. These samples were similar in age (early 20s), gender composition (67–80% female), and SES (18.50–18.60 on Kuppuswamy’s Socioeconomic Scale, Sharma et al. 2012).

The samples considered 21 values in addition to the two discussed here. The whole questionnaire was in Portuguese for the Brazilian sample and in English for the British sample. Participants were asked to list typical situations in which they considered each value to be important. Furthermore, they were asked to include a “short description of the people in the situation and what they do.” We consider these three aspects as a good representation for measuring instantiations. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that there may be other relevant aspects, for example, when one is interested in the role of instantiations in specific situations. The instructions provided two examples that pertained to two values not included in our measures and Schwartz’s value model: “For example, the value “enjoyment” could be relevant during leisure time. Relevant people in the situation can be friends and the family. They could spend time together at the beach or playing games at home.”

Participants were asked to list at least two to three instantiations for each value and up to 7 in total. From the 61 participants in the Brazilian sample, 30 responded to these questions for family security, 34 for protecting the environment, and 3 participants to both values. From the 60 participants in the British sample, 27 responded to family security, 35 for protecting the environment, and 2 participants to both values. The Brazilian instantiations were translated to English by an experienced translator and Portuguese native speaker.

Because the three open-ended responses for each value (“situation,” “people in the situation,” “what are they doing”) are all part of the instantiations, we analyzed them together. We separately analyzed each value in each sample using the Open Access program, Iramuteq, which is designed for content analysis. For all the analyses, the option lemmatization was chosen: Very similar words (e.g., people and person) as well as different verb forms (e.g., recycle, recycles, recycled) were treated the same. Furthermore, only nouns, verbs, and adjectives were analyzed.

Next, words that were mentioned at least ten times were analyzed. These words were read in their original context. That is, we looked at the whole responses where the specific words were mentioned in order to find a common theme. Furthermore, we looked at the similarity of responses for which the same words were mentioned, that is, if the participants used a certain word with the same meaning or with different connotations.

The responses of the Brazilian participants were for each value on average almost twice as long as the responses from UK participants (561 vs. 299 characters). However, the number of words that were mentioned at least ten times barely differed between the samples.

Our analyses revealed interesting results for both of the values considered here. For family security, two of the Brazilian participants’ typical instantiations entailed (a) providing support and advice (this was mentioned by 10 participants at least once) and (b) making sure every child is safe (5). For the British participants, typical instantiations also entailed (a) providing support and advice to family members, mostly after a negative event (16) and (b) making sure that the children are safe and staying in contact with family (mentioned by 6 participants). These two instantiations did not differ significantly between Brazil and the UK. However, as predicted, securing the family home against intruders (e.g., with electronic safety equipment, demanding more police on the street) was mentioned significantly more often in Brazil than in the UK (10 vs. 2, χ 2 = 5.33, p = 0.02).

For protecting the environment, we found significant differences for four instantiations. Brazilian participants were more likely to mention saving water (11 vs. 3), χ 2 = 4.57, p = 0.03 and planting trees (8 vs. 1), χ 2 = 5.44, p = 0.02. In contrast, British participants were more likely to mention changing their personal mode of transportation (e.g., from personal car to car-sharing, cycling) in order to protect the environment (14 vs. 2), χ 2 = 9.00, p = 0.003, and other means to reduce carbon emissions (i.e., general demands to reduce carbon emissions without specific examples; 7 vs. 1), χ 2 = 4.5, p = 0.03. For four other instantiations, no significant differences were found: throwing garbage into a bin, recycling, switching off the light if not needed, and demanding that companies should be more concerned about the environment.

Overall, the instantiations or exemplifiers differed significantly between Brazil and the UK. For family security, electronic safety devices like electric fences or police on the street were mentioned in Brazil as typical instantiations, reflecting the (need for) different security standards between the two countries. These safety measures were not as frequently mentioned in the UK, but respondents in both countries mentioned close contact and support for children.

For protecting the environment, typical instantiations were again related to the local context. In the region of Brazil where we conducted our study, not wasting or polluting water was likely mentioned often because water is scarce in the local countryside. In contrast, freshwater is plentiful in Cardiff. In Brazil, it is also common that everyone plants at least one tree in their life. This may explain why planting a tree was more likely to be seen as a typical instantiation for protecting the environment in Brazil than in the UK. In contrast, there are more bicycle lanes, a safer and more comfortable public transport system, and more focus on car-sharing in Britain than in Brazil. Therefore, it is not surprising that choosing a more environmentally friendly mode of transportation was mentioned more often in the UK.

The main focus here was on differences between countries. However, we assume that is also possible to observe differences within a country, based on different individual experiences, socioeconomic status, religion, gender, and other variables (Greenfield 2014). For example, people with lower income have less freedom to provide their children a safe and stable environment. Therefore, it can be speculated that, for instance, electronic fences and other rather expensive safety devices would be more likely to be typical instantiations of family security among Brazilians who are relatively wealthy than among those who are poor.

The focus here was on two values, family security and protection of the environment, but we expect that instantiations can differ for other values as well. We chose these two values merely as illustrations of the general principle. Additional data in our cross-cultural comparisons suggest important differences in instantiations for a number of other values, such as creativity, wealth, and social power, to name a few.

Crucially, the differences in typicality do not merely indicate that particular instantiations are relevant in some places, but not in others. For example, Brazilian participants spontaneously mentioned “saving water” more often as a situation in which protecting the environment is relevant. Does this mean that saving water is for British participants unrelated to protecting the environment or is it just less typical for them? To address this question, we have conducted a second study in which we have given 70 Brazilian and 44 British participants (all were students) numerous instantiations and asked them to choose one out of six values from Schwartz’s (1992) model that is most suitable for the given situation. Overall, most instantiations were correctly “back-translated” to the respective value (i.e., the correct value was chosen from the list of six as being applicable by the majority of participants), independent of whether the instantiation was mentioned more often by participants from one than the other country. For example, saving water, recycling, and walking instead of using the car for short distances were recognized by participants from both countries as being related for protecting the environment; at the same time, installing electric fences around the house was identified as an instantiation of family security in both nations. We consider these behaviors as instantiations of the values in both countries, but as being more typical instantiations of the values in the country where they were mentioned more often in spontaneous responses to the values.

Overall, our results suggest that value instantiations are ordered along a graded structure similar to categories used in cognitive psychology (Barsalou 1985, 1987), with the most typical instantiations at one end of the structure and atypical ones (e.g., those that are mentioned only in another country) at the other end. The instantiations vary in how good of an example they are for each specific value, with individual and regional variation in this “best fit.”

Conclusions

This chapter has described a number of reasons why it is important to study instantiations of human values and presented a methodology to assess them. Value instantiations provide us with more information about cross-cultural differences than values measured solely on an abstract level. Furthermore, value instantiations can help to explain why some behaviors are more strongly associated with values than others. Value instantiations can also explain why people in some countries do not differ on particular values (e.g., equality), but show differences on relevant attitudes and behavior (e.g., gender discrimination). Finally, the process of instantiation, though central to the role of values in everyday life, has, as a cognitive process, been almost entirely overlooked (see also Maio et al. 2009). Although research on value instantiation is in its early stages, findings are promising and taking value instantiations into account will likely lead to deeper insights into the connection between values, attitudes, and actions.

References

Armstrong, S. L., Gleitman, L. R., & Gleitman, H. (1983). What some concepts might not be. Cognition, 13(3), 263–308. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(83)90012-4

Arthaud-Day, M. L., Rode, J. C., & Turnley, W. H. (2012). Direct and contextual effects of individual values on organizational citizenship behavior in teams. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(4), 792–807. doi:10.1037/a0027352

Bardi, A., & Schwartz, S. H. (2003). Values and behavior: Strength and structure of relations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(10), 1207–1220. doi:10.1177/0146167203254602

Barsalou, L. W. (1985). Ideals, central tendency, and frequency of instantiation as determinants of graded structure in categories. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 11(4), 629–654. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.11.1-4.629

Barsalou, L. W. (1987). The instability of graded structure in concepts: Implications for the nature of concepts. In U. Neisser (Ed.), Concepts and conceptual development: Ecological and intellectual factors in categorization (pp. 101–140). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Evans, L., Maio, G. R., Corner, A., Hodgetts, C. J., Ahmed, S., & Hahn, U. (2013). Self-interest and pro-environmental behaviour. Nature Climate Change, 3(2), 122–125. doi:10.1038/nclimate1662

Feather, N. T., Woodyatt, L., & McKee, I. R. (2012). Predicting support for social action: How values, justice-related variables, discrete emotions, and outcome expectations influence support for the Stolen Generations. Motivation and Emotion, 36(4), 516–528.

Fischer, R., & Schwartz, S. (2011). Whence differences in value priorities? Individual, cultural, or artifactual sources. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42(7), 1127–1144. doi:10.1177/0022022110381429

Greenfield, P. M. (2014). Sociodemographic differences within countries produce variable cultural values. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45(1), 37–41. doi:10.1177/0022022113513402

Hampton, J. A. (1981). An investigation of the nature of abstract concepts. Memory & Cognition, 9(2), 149–156. doi:10.3758/BF03202329

Lord, C. G., Desforges, D. M., Fein, S., Pugh, M. A., & Lepper, M. R. (1994). Typicality effects in attitudes toward social policies: A concept-mapping approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(4), 658–673. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.66.4.658

Lord, C. G., Desforges, D. M., Ramsey, S. L., Trezza, G. R., & Lepper, M. R. (1991). Typicality effects in attitude-behavior consistency: Effects of category discrimination and category knowledge. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 27(6), 550–575. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(91)90025-2

Lord, C. G., Lepper, M. R., & Mackie, D. (1984). Attitude prototypes as determinants of attitude–behavior consistency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(6), 1254–1266. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.46.6.1254

Maio, G. R. (2010). Mental representations of social values. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 42, pp. 1–43). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Maio, G. R., Hahn, U., Frost, J.-M., & Cheung, W.-Y. (2009). Applying the value of equality unequally: Effects of value instantiations that vary in typicality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 598–614.

McCloskey, M. E., & Glucksberg, S. (1978). Natural categories: Well defined or fuzzy sets? Memory & Cognition, 6(4), 462–472. doi:10.3758/BF03197480

Monteiro, L. T. (2012). The valley of fear—The morphology of crime, a case study in João Pessoa, Paraíba, Brasil. In M. Greene, J. Reyes, & A. Castro (Eds.), Proceedings of the eighth space syntax symposium. PUC: Santiago de Chile.

Office for national statistics. (2014). Chapter 2—Homicide. Retrieved from http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171776_352260.pdf

Pozzebon, J. A., & Ashton, M. C. (2009). Personality and values as predictors of self- and peer-reported behavior. Journal of Individual Differences, 30(3), 122–129. doi:10.1027/1614-0001.30.3.122

Rogers, T. T., & Patterson, K. (2007). Object categorization: Reversals and explanations of the basic-level advantage. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 136(3), 451–469. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.136.3.451

Rosch, E. (1973). Natural categories. Cognitive Psychology, 4(3), 328–350. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(73)90017-0

Rosch, E. (1975). Cognitive reference points. Cognitive Psychology, 7(4), 532–547. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(75)90021-3

Rosch, E., Mervis, C. B., Gray, W. D., Johnson, D. M., & Boyes-Braem, P. (1976). Basic objects in natural categories. Cognitive Psychology, 8(3), 382–439. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(76)90013-X

Rosch, E., Simpson, C., & Scott, R. (1976). Structural bases of typicality effects. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 2(4), 491–502. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.2.4.491

Roth, E. M., & Shoben, E. J. (1983). The effect of context on the structure of categories. Cognitive Psychology, 15(3), 346–378. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(83)90012-9

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 1–65.

Schwartz, S. H., & Bardi, A. (2001). Value hierarchies across cultures taking a similarities perspective. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(3), 268–290. doi:10.1177/0022022101032003002

Schwartz, S. H., Melech, G., Lehmann, A., Burgess, S., Harris, M., & Owens, V. (2001). Extending the cross-cultural validity of the theory of basic human values with a different method of measurement. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(5), 519–542. doi:10.1177/0022022101032005001

Sharma, A., Gur, R., & Bhalla, P. (2012). Kuppuswamy’s socioeconomic scale: Updating income ranges for the year 2012. Indian Journal of Public Health, 56(1). Retrieved from http://xa.yimg.com/kq/groups/20489237/1194520481/name/IndianJPublicHealth561103-2787554_074435.pdf

Shultziner, D. (2003). Human dignity—Functions and meanings. Global Jurist Topics, 3(3). Retrieved from www.researchgate.net/profile/Doron_Shultziner/publication/241002874_Human_Dignity_Functions_and_Meanings/links/00b7d522ad17e53070000000.pdf

Statista. (2014). Ranking of the most dangerous cities in the world in 2013, by murder rate per capita. Retrieved from http://www.statista.com/statistics/243797/ranking-of-the-most-dangerous-cities-in-the-world-by-murder-rate-per-capita/

Tansel, A., Dalgic, B., & Guven, A. (2014). Wage inequality and wage mobility in Turkey (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. Available at SSRN 2519502). Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. Retrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2519502

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support by the School of Psychology, Cardiff University (www.psych.cf.ac.uk), the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC; www.esrc.ac.uk) to the first and last author (ES/J500197/1), and the CAPES Foundation (Brazil, http://www.capes.gov.br/) to the second author. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hanel, P.H.P., Vione, K.C., Hahn, U., Maio, G.R. (2017). Value Instantiations: The Missing Link Between Values and Behavior?. In: Roccas, S., Sagiv, L. (eds) Values and Behavior. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56352-7_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56352-7_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-56350-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-56352-7

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)