Abstract

This chapter addresses the dynamic, reciprocal, and transactional relations between the experience of parenting stress and parent’s sense of self-efficacy. Taking a broad perspective on self-efficacy, we examine the complex links between parenting stress and parenting self-efficacy as predictor, mediator, and consequence of parenting stress. Although the evidence for adverse influence is compelling regardless of direction of effect, many questions and issues remain to be addressed in the way parenting stress processes operate within the family. Emphasis is placed on the need to consider parenting stress from more developmental and systemic perspectives, and a model is proposed to capture more of the systemic complexity involved. The chapter focuses on the mechanisms through which parenting stress may influence and be influenced by broader parenting perspectives, including coparenting processes and potential differences between mothers and fathers. Directions for future research are offered.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Among determinants of parenting, few constructs have engendered the kind of attention as has stress. Since Belsky’s seminal determinants paper in 1984, and to some degree even before, stress has had a prominent place in understanding why parents parent the way that they do. The effect of stress on parenting, especially the adverse influences on aspects of parental efficacy, has been studied extensively across the last several decades. Indeed, it has become almost typical that studies of the determinants of parenting, especially if any risk condition is present, include some measurement of reported stress.

Several conceptual frameworks for understanding parenting stress currently exist and influence the nature of the research that has been done to explicate the construct. Despite differences in conceptualizations, the defining characteristics of parenting stress are similar and are well captured by Deater-Deckard’s (2004) description of parenting stress as “a set of processes that lead to aversive psychological and physiological reactions arising from attempts to adapt to the demands of parenthood” (p.6). Given these defining qualities, it is reasonable to expect that parenting stress would present a significant challenge to parents’ self-efficacy and sense of competence or well-being.

It is nevertheless important to recognize here that parenting stress cannot be simply viewed as an attribute or response of an individual mother or father at any one point in time. A mother’s or father’s perception of parenting stress and the implications of that experience reflect systemic processes within the family that are transactional, reciprocal, bidirectional, and developmental in their function. To date, a more systemic developmental perspective has not characterized the general approach to research on parenting stress. But in addressing the connections between parenting stress and parental self-efficacy, this chapter will promote approaches to understanding relations between parenting stress and parental functioning that encourage more systemic developmental perspectives.

Before delving more deeply into issues related to parenting stress, we first address conceptual perspectives on parental self-efficacy and the reasons why its links to parenting stress may be particularly important. Next, we address a number of critical issues in the conceptualization of parenting stress, with a particular eye toward its measurement, its developmental implications, and the transactional, systemic nature of the construct. From those perspectives, we then examine the evidence that links parenting stress to a variety of parenting processes, promoting a focus on reciprocal, transactional, and systemic perspectives. We conclude with a few recommendations for future research directions.

Parenting Self-efficacy

As O’Neil, Wilson, Shaw, and Dishion (2009) indicate, parental efficacy draws much from the basic concept of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977), and parental self-efficacy (Glatz & Buchanan, 2015) addresses the extent to which parents believe they have the ability to influence their children’s development and the contexts in which that development takes place. The expectation that one is efficacious as a parent is derived from multiple sources of input (O’Neil, Wilson, Shaw, & Dishion 2009), including parents’ direct experience with their children and the nature of ecological contexts in which one’s parenting experience occurs (Glatz & Buchanan, 2015). In this sense, parental self-efficacy emerges from the same experiential context as does parenting stress, giving rise to the likelihood that the two constructs might well align and that parenting stress may serve to change parental efficacy over time. There is some evidence that parental self-efficacy does change over time, increasing during early childhood (Weaver et al., 2008) only to decrease as children enter adolescence (Glatz & Buchanan, 2015). Whether such change can be tied to parenting stress is an important question for which the answer is not yet entirely known.

We have speculated before about whether parenting stress can serve as a change agent over time (Crnic & Low, 2002), essentially reducing parents’ sense of their own efficacy as children develop and changing the nature or quality of parent–child relationships. The answer to whether such pathways of influence exist has not yet been fully explicated, but the effort to better understand the links between parenting stress and parent efficacy offers some important indications that there may be merit to such suggestions.

Nevertheless, when it comes to parenting, it seems clear that experience matters. There is a wealth of evidence that having the opportunities to develop mastery is an effective way to increase self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977), and indeed, parents with multiple children report higher parental self-efficacy than do parents of single children (Leahy-Warren & McCarthy, 2011). On the other hand, there is also evidence to suggest that parents with more children report higher parenting stress (Crnic & Greenberg, 1990; Skreden et al., 2012; Spinelli, Poehlmann, & Bolt, 2013), balancing the effect of experience with the pressures of increased demand on parents.

Parents with high self-efficacy feel competent in the parenting role, have a sense that they can successfully accomplish parenting tasks, and believe that they can exert positive influence on a child’s developmental competence. Parenting attitudes, parenting beliefs, and parenting behaviors are all relevant to this sense of self-efficacy, and each of these characteristics has some degree of impact on child development. Child characteristics, behavior, and relational qualities are also critical to parents’ self-efficacy and may be more important than are the ecological contexts in which the parent–child relationship exists (see also McQuillian and Bates, Chap. 4 this volume; Glatz & Buchanan, 2015). Again, these attributes of parental self-efficacy share important features with parenting stress, which is also highly dependent on parental perspectives, children’s developmental and behavioral qualities, and the quality of the parent–child relationship.

We are all likely to agree that parenting competence and self-efficacy (PSE) are important attributes of successful parenting (Shumow & Lomax, 2002; Teti & Gelfand, 1991) and are linked with a variety of positive and negative outcomes for parents and for children (Jones & Prinz, 2005). Identifying those factors that create risk for parenting competence is therefore important in constructing models for successful child development. The relations between parenting stress and parental self-efficacy are reciprocal, and the direction of effect can travel in either way. Further, there are likely to be critical pathways of influence at play. It may be that compromised parenting self-efficacy, in whatever form, can be a direct consequence of parenting stress. There is evidence to support such simple direct effects. On the other hand, it is likely that there are more complex pathways of influence in operation in which the links between parenting stress and parental self-efficacy are allied in mediated processes with implications for emerging parent and child well-being. Further, even more complex pathways that delineate moderated mediation processes (or vice versa) are also possible. For example, early parenting stress may predict later parental psychological distress (e.g., more depressive symptoms), but the effect may be indirectly affected (mediated) by parental self-efficacy. But, that mediated pathway may only be present under conditions where social support does not exist.

Conceptually, high parenting stress should have an adverse effect on parenting self-efficacy, creating doubt and hesitation or irritation and impulsive parental responding. On the other hand, low parent self-efficacy may well lead parents to perceive children’s behavior and parenting processes as more stressful. Either direction is reasonable to assume and may in fact take place within the parent and parent–child dyad. Research models pursue both directions in an attempt to understand the complex interplay between parenting stress and parenting self-efficacy. But regardless of the directional conundrum, the relation between parenting stress and parenting self-efficacy is transactional; that is, the two factors affect one another across time. This renders the direction of effect issue as subject to the specific question at hand, and the timing of when that question is asked. Once a link is established between parenting stress and parenting self-efficacy, they become reciprocally influential to one another in ways that serve to perpetuate the connection. As the parent is stressed, she or he feels less efficacious. As efficacy becomes more compromised, parenting becomes more stressful, and the cycle is maintained between the two interdependent constructs.

Preliminary Considerations in Linking Parenting Stress and Parent Self-efficacy

In exploring the links between parenting stress and parenting efficacy, there are multiple issues to consider that help to define and explicate the nature of the connections that may exist. These issues are particularly germane to the synergy between parenting stress and parenting self-efficacy but are tied more specifically to parenting stress as an independent construct as well.

Conceptual Bases and Limitations

It is difficult to reach a full understanding of the implications of parenting stress on later competencies without addressing the ways in which it is has been both conceptualized and measured. Crnic and Low (2002) as well as Deater-Deckard (2004) have provided discussions of the issues and approaches, differentiating the more problem-focused parent–child-relationship (P-C-R) framework exemplified by Abidin’s (1992) model, and the more normative, everyday experiential basis of parenting daily hassles (PDH) as indexed by the approach of Crnic and Greenberg (1990). By far, the majority of the research on parenting stress has utilized the P-C-R model and Abidin’s (1995) Parenting Stress Index (PSI), and most often now its reliable and useful three-scale short form. As Deater-Deckard (2004) suggests, the PSI is most typically used with clinical or risk samples in which parenting stress is thought to be highly salient as a predictor of some adverse condition or a result of some problematic function. In contrast, the PDH targets more normative and adaptive everyday stresses that are typical of child behavior and parenting responsibilities, although it has important functions with risk groups as well (e.g. Gerstein, Crnic, Blacher, & Baker, 2009). Both approaches offer important perspectives on the parenting stress process, with some shared focus but divergent emphases. Beyond the American-focused approaches, the Swedish Parenthood Stress Questionnaire (SPSQ; Östberg, Hagekull, & Wettergren, 1997) was developed based on the model presented by Abidin’s (1995) PSI but expanded on that framework to address broad elements of parenting along five scales (incompetence, role restriction, social isolation, spouse relationship problems, and health problems). There has been an emphasis on parenting stress research in Scandinavian countries, and the SPSQ has been used and validated in Sweden and Norway.

The fundamental difference between the P-C-R approach and that of the parenting daily hassles approach is the emphasis on existing problematic function. In many ways, the P-C-R model assumes that the presence of some problematic status (parental distress, child behavior problems, and parent–child relationship conflict) is stressful, which adversely affects the parenting context. Certainly, there is a wealth of evidence to support that conceptual connection. Nevertheless, it is not surprising that parenting stress measured within this framework would be associated with problematic functioning as the measure itself indexes existing problems in the family context.

The daily hassles approach, in contrast, identifies parenting tasks and child behaviors that reflect everyday experience that is essentially normative (sibling conflicts, child whining/complaining, repeatedly cleaning up messes, picky eating, etc.) but may be considered stressful, especially in the cumulative experience of the events over short periods of time. The measurement paradigm for parenting daily hassles (Crnic & Greenberg, 1990) judges parent response along two dimensions: the frequency with which parents experience each event (frequency scale) and the degree to which the event is judged to be stressful or irritating (intensity scale). Both frequency and intensity are rated separately along a 5-point scale for each item, providing indices that reflect how often parents experience these parenting events and how much they perceive them to be stressful. It is meant to capture normative rather than problematic experience but still discriminate between parents that are more and less stressed by the everyday parenting experience.

The P-C-R and parenting daily hassles approaches are not conflicting but are more complementary in what they offer current conceptualizations of parenting stress. Integrating the two may provide more robust perspectives on systemic family stress experience, capturing both the risk and normative processes through which most families evolve across the developmental periods that are characterized by caregiving.

Source of Stress

There is a need to distinguish between stressed parents and parenting stress. A stressed parent may result from any number of circumstances outside the context of the family or caregiving. Job stress, economic stress (see Cassells and Evans, Chap. 2 this volume), and interpersonal relationship stress may all contribute. There are large literatures on these stress contexts, and it is outside the scope of this chapter to detail those relations. Parenting stress, however, involves stressors that are tied specifically to the context of caregiving, parent–child relationships, and the broader parenting role (see Nomaguchi and Milkie, Chap. 3 this volume). This is not without its controversy (see measurement issues below). How we conceptualize and measure stress, and particularly how we measure parenting stress, is critical to understanding the various phenomena in which we are interested. Several studies that we have conducted that have included both measures of life stress and parenting stress indicate that parenting stress predicts parenting attitudes and behavior not only above and beyond the contribution of non-parenting related major life stresses, but also differentially (Crnic & Greenberg, 1990; Crnic, Gaze, & Hoffman, 2005).

Developmental Functions

One of the elements in the connection between parenting stress and parenting self-efficacy that has received far too little attention is the obvious developmental implications of this phenomenon. The literature has been woefully inadequate in considering the implication of child age and the likely differences across the developmental period that come into play in the connections between parenting stress and parenting processes. Parents of infants, toddlers, preschoolers, school-age children, and adolescents all face different developmental challenges with their children. Yet, there is a tendency to treat parenting stress as if it is a stable and coherent construct across the developmental period with little concern for the obvious developmental differences that may exist. There are exceptions, such as Spinelli et al. (2013) from four months to three years; Crnic and Booth (1991) across ages one, two, and three; Crnic et al. (2005) across ages three to five; Deater-Deckard, Pinkerton, and Scarr (1996) from preschool to early school age; and Putnick et al. (2010) across ages 10–14 years. Most of these studies that look across age spans, albeit relatively brief spans, find few differences in absolute amounts of parenting stress experienced by parents at differing ages or find strong stability across periods that are measured.

Although absolute stability and levels of stress may be similar when measured in the studies above, such analyses do not necessarily provide a full accounting. It could be that it is not the amount of stress that varies or changes, but the specific facets of parenting or child behavior that change across time. The parent of the preschooler and the parent of an adolescent may perceive the stressfulness of their parenting similarly on a general level, but the behaviors and childrearing responsibilities that create that stress are likely quite different and may have different implications for parent self-efficacy or other parenting attributes. The stability in parenting stress might also suggest that perceived parenting stress is more an underlying parent personality marker than an objective index of unique stressful experience, an explanation that has been raised by others as well (Deater-Deckard, 2004). Regardless, it is imperative that broader, more focused efforts be made to identify the underlying developmental processes that may differentiate the experience and effects of parenting stress from infancy through adolescence.

Systemic Considerations

One of the major shortcomings in parenting stress research to date is the fact that we do not tend to treat parenting stress as a systemic construct despite the fact that it truly reflects more multifaceted and multileveled influence than individual factors. Indeed, individual studies tend to focus on parenting stress related to a specific child at a particular age in families, as most studies are interested in targeted developmental phenomena. However, families often have children of other ages at home, even if those children are not the focus of the research of interest. Parents with multiple children are often asked to respond to parenting stress instruments in the context of the specific child of interest despite the fact that the stress of parenting comes from more than just the experiences related to a single child. That is, parenting stress is a dynamic construct that likely represents the cumulative and integrated influence of all children in the home or may differ for sibling children within the same home, as Deater-Deckard, Smith, Ivy, and Petrill (2005) have demonstrated. Further, there is evidence that the number of children in the home matters for parents’ experience of stress (Crnic & Greenberg, 1990). The nature of such influence, however, may be dependent on the number and ages of the children and the specific research question at hand.

Another systemic factor involves the idea that mothers and fathers are not necessarily interchangeable in their perspectives on parenting stress. There is some evidence that there are similarities as well as differences between mothers and fathers with respect to parental self-efficacy (Jones & Prinz, 2005). Additionally, the differences in how mothers and fathers might perceive the stressfulness of parenting could present some interesting contrasts (Deater-Deckard, 2004) but have not really been studied in depth. How does mothers’ stress affect fathers and fathers’ stress affect mothers in the context of the family and individual parenting processes? These issues of influential crossover effects are addressed later in this chapter.

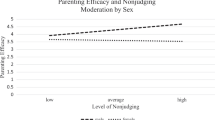

To address the systemic, dynamic nature of parenting stress, we offer a conceptual model that attempts to incorporate the salient elements that reflect the complex systemic nature of parenting stress as it might be related to parenting self-efficacy and beyond to any number of related parent and child competencies. The model (see Fig. 11.1) attempts to portray the complexity inherent in the reciprocal, bidirectional nature of the relations between parenting stress and parenting across time as well as indicates the possibility for crossover effects between caregivers that can be either direct or mediated. Further, child factors (e.g., developmental considerations and number of children) and family system attributes (e.g., marital functions and coparenting) both contribute to parenting stress processes and are affected by them over time. These complex transactional processes in turn have both immediate and longer term consequences for the well-being and competence of parents and children in the family.

Measurement Issues

Measuring stress, whether specific to parenting or not, is fraught with a number of methodological conundrums, and cautions are required regardless of the approach. These have been well detailed elsewhere (Crnic & Low, 2002; Deater-Deckard, 1998, 2004; Reitman, Currier, & Stickle, 2002) but involve concerns such as the objective versus more subjective appraisal of stressors and the extent to which stress indices may be contaminated by mood or affective wording, the latter which makes it difficult to differentiate between the stress predictor and psychological distress or other outcomes of interest. We are wise to be aware of the caution raised some time ago about the confound of “symptoms predicting symptoms” in the link between stress and psychological outcome (Dohrenwend & Shrout, 1985).

Evidence for Adverse Influence on Parenting Efficacy

In connecting parenting stress and parenting self-efficacy, research has taken a broad perspective with respect to what might reflect efficacy in the parenting role. Certainly, direct measures of parent beliefs about their own parenting self-efficacy are obvious targets, but there are multiple indirect markers that include a range of other parenting attitudes and beliefs, parenting styles, parent well-being or distress, parenting behaviors, and even more systemic family markers such as marital relationship quality and coparenting processes. We touch on each of these below.

Efficacy Beliefs

With an explicit focus of this chapter on the link between parenting stress and parental self-efficacy, it is worth exploring the central proposition that the experience of parenting stress is associated with direct makers of lower self-efficacy in parenting. Despite what must seem as a fairly intuitive relation to pursue, there is surprisingly little direct evidence that has accrued. Only a few studies have specifically assessed relations between parenting stress and parental self-efficacy, and the findings are consistent with expectations (e.g., Jones & Prinz, 2005). In a study of parents of clinically identified behavior problem preschoolers (Scheel & Rieckmann, 1998), parenting stress and parent self-efficacy were negatively related (r = −.62), and parenting stress predicted parental self-efficacy over and above the contribution of other indices of family functioning. Jackson and Huang (2000) likewise found that mothers of preschoolers who experienced more parenting stress reported less self-efficacy, and mothers’ self-efficacy in turn mediated the relations between parenting stress and parenting behavior. In this case, parenting stress was indexed by a subset of seven items from the PSI, and parenting behavior was represented by a set of report and observational items from the HOME (Caldwell & Bradley, 1984). More recently, Dunninga and Giallo (2012) explored the connections between fatigue, parenting stress, and parent self-efficacy in mothers of infants, finding that parenting stress was negatively associated with parent efficacy, and in fact, mediated the relation between fatigue and maternal self-efficacy. This study supports the direct linkage not only between parenting stress and lower parent self-efficacy, but also between parental fatigue and parenting stress, which has important implications for emerging biopsychosocial models of parent health.

In all, the evidence supports the notion that parenting stress and parent efficacy are linked such that greater stress coincides with lower efficacy. Although direction of effect is indeterminant, or could certainly operate in either direction, it nevertheless follows that parental efficacy and its correlates might well be at risk under conditions in which parenting stress is high. Indeed, research not only tends to lead to such straightforward conclusions, but also suggests that there is a fair amount of nuance and specificity in the ways in which parenting stress is linked to broadly conceived markers of parental efficacy and competence.

Parent Psychopathology

We have all heard the classic parent refrain of “you kids are driving me crazy!” The extent to which that might literally be true has been the subject of a fair amount of research and not a small amount of interest. The connection between parenting stress and parent psychological distress is again one in which the pathways of influence are complex. It seems likely that parenting stress can lead to the experience of some psychological distress for mothers and fathers, and indeed, a wealth of evidence is available to support such connections. However, the evidence in support of a pathway from parenting stress to diagnosable disorder is less obvious. Although studies that connect parent depression and anxiety with parenting stress are apparent, it is often more typically dysphoria or anxious symptoms that are addressed as opposed to a specific diagnosed disorder. Thus, it is less clear that stresses associated with the parenting role are alone sufficiently robust to lead to clinical disorder. In contrast, the pathway from existing parental psychopathology to the experience of greater parenting stress is more conceptually robust, and existing research provides clear support for this linkage.

In the end, it may not matter whether there is a specific mental health diagnosis or not, as parental well-being is important in its own right and connects up well with other parenting processes to affect both parent and child functioning. Thus, understanding the ways in which parenting stress and various indices of parent well-being covary is an important goal. Consistent with stress research in almost any context, parenting stress and parental well-being are inextricably tied together such that higher stress is associated with less parental well-being (Cheah, Leung, Tahseen, & Schultz, 2009; Lamis, Wilson, Tarantino, Lansford, & Kaslow, 2014; Skreden et al., 2012). But again, the nature of these effects and the mechanisms that drive them are more complex than simple main effect models would suggest. The Skreden et al. (2012) study of Norwegian parents of preschoolers indicates that the processes by which mothers’ and fathers’ well-being is affected are differentially related to factors associated with parenting stress (e.g., social isolation and role restriction), and Cheah and colleagues (2009) present evidence to show the moderating influence of parenting stress on the connections between well-being and parenting styles.

Among indicators of parent distress, perhaps most frequently studied is parental depression, and especially maternal depression. Studies involving parental anxiety follow closely after that. In either case, the connections between symptoms and parenting stress are reliably strong and in the expected direction to indicate that greater parenting stress is linked to the endorsement of more symptoms (Delvecchio, Sciandra, Finos, Mazzeschi, & Di Riso, 2015; Gray et al., 2012; Nygren, Cartensen, Ludvigsson, & Frostell, 2012; Pripp, Skreden, Skari, Malt, & Emblem, 2010; Shea & Coyne, 2011; Skreden et al., 2012; Thomason et al., 2014). Further, parenting stress leads to decreased parental self-efficacy, and decreased parental efficacy has been found to be related to lower parental well-being and more depressive symptoms (Jones & Prinz, 2005; O’Neil et al., 2009). With respect to differences between mothers and fathers, the evidence does not clearly suggest that stress has differential effects on well-being for women and men. In some studies, mothers report more stress and more symptoms/less well-being than fathers (Skreden et al., 2012), whereas in others, such differences fail to emerge (Solmeyer & Feinberg, 2011).

The major issue with much of the research on parenting stress is that it relies on parent report to identify the extent of parent symptoms as well as the degree of parenting stress and is therefore subject to shared method variance biases. Much of it is also single point in time, cross-sectional research, which means that direction of effect cannot easily be discerned. Longitudinal studies that connect symptoms with parenting stress and offer the structural models necessary, or the cross-lagged analyses that are likely to help untangle the directionality issues, are simply too few. Nonetheless, Thomason et al. (2014) offer some compelling longitudinal findings that demonstrate the complexity of the connections that may exist, at least during infancy. Exploring overall parenting stress as well as the three short-form scales from the PSI, they demonstrated that overall parenting stress served to predict later maternal depressive symptoms in a cross-lagged analysis assessing parenting stress and depression across three-, seven-, and 14-months postpartum. However, when parenting stress components were examined individually, the findings became less consistent. For the parental distress scale, there were no cross-lagged effects to later depression. For the difficult child scale, depressive symptoms predicted stress rather than the other way around, and finally for the parent–child dysfunctional interaction scale, bidirectional cross-lagged relations emerged, but the model fit indices were poor. Other longitudinal research suggests that parent symptoms measured in infancy can lead to higher levels of reported parenting stress later (Pritchard et al., 2012). The high-risk nature of this sample may account at some level for the differences between these results and those of Thomason et al. (2014).

Whether the link between parenting stress and parental psychopathology is initiated by parental distress that leads to subsequent parenting stress or vice versa, it is likely that the process becomes transactional and cyclical, creating an ongoing feedback loop in which each factor facilitates the experience of the other across time. Depending upon child age and where in the cycle measurements are taken, one factor or the other may appear to be the precipitant. Minimally, we need to extend our research models beyond cross-sectional approaches as well as beyond the early childhood period to more fully understand the interplay between parenting stress and distress in parents.

Parenting Styles

One common focus of much of the research which has explored the connection between parenting stress and parenting processes has been on parenting styles, broadly conceived to represent parents’ general approach to or attitudes about children and child rearing. In some early work, parent’s perspectives about the complexity of child development showed some interesting relations to parenting stress (Crnic & Booth, 1991), such that the degree to which mothers were stressed depended on the complexity with which they viewed development. For mothers who viewed development as complex and dynamic, parenting younger children was perceived as more stressful. For parents who viewed development in more concrete or simple terms, preschoolers were perceived to be more stressful. This suggests the importance of developmental perspectives on parenting stress processes, as parents sense of the stresses associated with childrearing may depend to some extent on children’s growing behavioral repertoires or skills and the goodness of fit with parental expectations about development.

More commonly, research on parenting stress has examined the connection to traditional parenting styles such as those identified by Baumrind (1991). Low parenting stress has been associated with more authoritative parenting styles, even when otherwise supportive contexts may be available to parents (Cheah et al., 2009). Likewise, parenting stress has been associated with inconsistent or more punitive parenting practices that are aligned with more authoritarian approaches (Shea & Coyne, 2011), as well as more demanding and less responsive parenting (Ponnet et al., 2013). Interestingly, even adolescents’ reports about the parenting style of their parents (acceptance/rejection versus psychological autonomy/control) have been shown to connect to parent’s report of parenting stress (Putnick et al., 2010), providing greater context for validation of the association.

Other attitudes and beliefs tend to confirm these same links, such that parenting stress connects in theoretically consistent ways with parents’ perceptions of various parenting correlates. For example, parents who report high stress also report lower parenting satisfaction (Crnic & Greenberg, 1990), less perceived support (Cheah et al., 2009; Crnic & Greenberg, 1990), poorer reactions to child negativity (Mackler et al., 2015), less cognitive readiness to parent (Chang et al., 2004), and more perceived ecological (neighborhood) disorder (Lamis et al., 2014). This latter link is relevant to parenting stress in disadvantaged groups where it can be difficult to parent effectively in neighborhoods that are less safe, contributing to increased parenting stress and more hostile parenting.

Observed Parenting Behavior

Much the same as with parenting beliefs and attitudes, parental self-efficacy can be judged by the quality of the behavior that parents display during interactions with their children. Parental self-efficacy influences the degree to which parents feel capable of managing developmentally salient processes with their children in support of the child’s emerging competence, which can obviously be represented in the quality and consistency of the behavior displayed in parents’ interactions with their children. Indeed, parent self-efficacy is heavily influenced by parents’ experiences with their children and the quality of the parent–child relationship that exists.

A wide range of parenting behaviors has been studied in relation to parenting stress. Chief among these have been parental affect (positivity and negativity), sensitivity, involvement, and intrusiveness. In general, greater parenting stress is associated with more negative parenting behavior, and this is true across developmental periods of interest (Gerstein & Poehlmann-Tynan, 2015; Harden, Denmark, Holmes, & Duchene, 2014; Mills-Koonce et al., 2011). However, such findings are not ubiquitous, and there are indications that some indices of parenting stress are associated more with less positive parental behavior than they are with more negative parenting behavior (Crnic et al., 2005; Jackson & Huang, 2000; Spinelli et al., 2013). For example, in our research, parenting daily hassles were strongly predictive of less maternal positivity and less dyadic pleasure in interactions with five-year-old children but did not predict more maternal negativity or greater dyadic conflict. It may be that these more normative daily hassles may operate to suppress parental positivity than increase parental negativity, although that remains to be further explored across child ages and samples.

Parenting behavior is often conceptualized as a mediator that serves to connect parental experience of stress with some untoward or adverse outcome, usually something associated with problematic competence in the child. This is sensible, as it is difficult to make the conceptual argument that parents’ experience of parenting stress directly affects some child specific competence. It is easier to make an argument for a direct effect on the parent such that their psychological well-being, their satisfaction with parenting, or the quality of their behavioral interactions might all be directly affected by the experience of stress associated with parenting.

Indeed, multiple studies have attempted to explore the nature of the mediated pathways linking parenting stress with some important child outcome, surmising that the effect of parenting stress on poor child outcomes is mediated through the effect that parenting stress has on parenting behavior. This describes a process by which the experience of parenting stress influences the nature of parent behavior, likely creating greater negativity, more intrusiveness, less positivity, and/or less sensitivity. In turn, those less optimal parenting behaviors lead to more problematic development in the child. Despite the compelling conceptual argument for such pathways, the evidence in support of such indirect influences is not uniformly compelling (Anthony et al., 2005; Crnic et al., 2005; Mackler et al., 2015). Identifying salient pathways of influence between stress and parenting behavior in the service of child and family competencies merits much further attention given its conceptual coherence.

Coparenting Processes

Recently, attention has begun to develop toward more systemic influences in families, and work on parenting stress has begun to follow. In particular, attention to coparenting processes, as well as marital relationships, has engendered some interest. Coparenting involves the way parents coordinate their parenting, support or undermine each other, and manage conflict regarding childrearing (Minuchin, Rosman, & Baker, 1978). Coparenting processes have been shown to be especially salient to parental adjustment, parenting processes, and child developmental and behavioral competencies (Feinberg, Kan, & Hetherington, 2007; Gable, Crnic, & Belsky, 1994). Further, coparenting has been found to both mediate and moderate the influence of individual parent characteristics, couple relationship quality, and parenting stress on various parenting and child adjustment factors (Feinberg, 2003).

Coparenting provides a prime context for exploring the ways in which parenting stress may affect systemic processes in families. And unlike more individual parenting processes, the connections between parenting stress and coparenting might take various forms, both positive and negative. Parenting stress might undermine parents’ abilities to work together, but it is also possible that a parent under stress might also rely on their partner to help encourage a consistent and coherent parenting framework. In the latter case, parenting stress might facilitate more cooperative or compensatory processes between parents. To date, evidence is most suggestive that when mothers’ and fathers’ combined parenting stress is low, parents are better able to coparent effectively (Feinberg, Jones, Kan, & Goslin, 2010), and coparenting intervention effects are better sustained when mothers and fathers experience less parenting stress.

Several recent longitudinal studies also indicate some important connections between parenting stress and coparenting processes. Using longitudinal survey data to study supportive coparenting processes, Schoppe-Sullivan, Settle, Lee, and Kamp Dush (2016) explored several connective pathways between coparenting and parenting stress. Their findings suggested that fathers’ (but not mothers’) perceptions of supportive coparenting at three months postpartum mediated the associations between their own (fathers’) anxious adult attachment during the third trimester of pregnancy and their parenting stress six months later. Additional tests of moderation revealed that mothers’ perceptions of greater supportive coparenting were associated with lower parenting stress only when their parenting self-efficacy was low, but fathers’ perceptions of greater supportive coparenting were associated with greater parenting satisfaction only when their parenting self-efficacy was high. This is a prime example of the complex and nuanced relations between parenting stress and parenting processes that emerge when multidimensional longitudinal models are employed. Similar evidence can be found in work by Delvecchio et al. (2015), who reported that levels of family maladjustment and parenting stress were mediated by the quality of the coparenting alliance.

Coparenting offers a window into understanding systemic effects of parenting stress, and to a certain extent, coparenting may reflect on the marital relationship. Surprisingly, there has been precious little study of parenting stress and marital relationship quality, or the bidirectional pathways that might detail relations between parenting stress, marital quality, and parenting efficacy. Over and above the effects of general social support, a positive marital relationship may act as a buffer in the face of high parenting stress (Gerstein et al., 2009; Robinson & Neece, 2015), may predict levels of parenting stress (Williford, Calkins, & Keane 2007), or may be influenced by parenting stress.

Certainly, the construct of “marital quality” has been conceptualized in a number of different ways across studies, highlighting its diverse role in understanding parenting more generally, and parenting stress, more specifically. Despite the likely bidirectionality in relations between parenting stress and marital quality, most studies have examined these factors independently as predictors of parenting behaviors (e.g., Ponnet et al., 2013) or have considered marital quality as a moderating variable. Future directions should continue to consider the pathways of influence that illuminate the mechanisms by which parenting stress and marital quality work together to influence parenting.

Research indicates that poor parent–child relations have been linked to hostile marital relationships (Katz & Gottman, 1996), which may be especially salient for fathers who (more so than mothers) are found to withdraw from their children and/or respond in coercive ways as a result of marital conflict (Crockenberg & Covey, 1991). Given that mothers more often take on the primary caregiving role, it may be easier for mothers to separate marital conflict from the role as a mother whereas for fathers, this “spillover” into the father–child relationship is harder to avoid. Interestingly, however, specific dimensions of hostile mother–father interactions (which could involve coparenting) may be more predictive of parenting than broad measures of marital quality. It has been noted that marital hostility is associated with fathers’ negative parenting behaviors only when this hostility occurred during marital conflict resolutions. For mothers, behaviors suggestive of child rejection were a result of withdrawn behavior of fathers during marital conflict (Katz & Gottman, 1996). From a family-systems perspective, efficacy in the parenting role can be influenced by interactions with others, especially individuals that share a close relationship (Merrifield & Gamble, 2013). Consistent with a “spillover” hypothesis, partners that feel unsuccessful in their marital relationship may also distrust their own efficacy in the parenting role.

Spillover is a within-person phenomenon whereby functioning in one psychological domain affects or becomes associated with functioning in another, different domain such as the connections between fathers’ marital functioning and father–child relationship factors described above. In contrast, “crossover effects” between parents are more systemic processes that could and should be much more emphasized with respect to parenting stress. Crossover occurs when an individual’s functioning in one domain affects or is associated with another individual’s functioning in one or more relevant domains. In the case of parenting stress, it may well be that one parent’s experience crosses over to have a direct influence on the partner’s perceived stress or functioning in other parenting domains. One investigation by Putnick et al. (2010) highlights the potential importance of such crossover effects involving parenting stress. In their study of parents of young adolescents, Putnick et al. (2010) showed that mothers parenting stress has relatively minor influence on fathers’ parenting stress, as maternal distress (the PSI subscale) at child age 10 had a small but meaningful effect on father distress at child age 14. In contrast, fathers’ stress at child age 10 had consistently broader and larger relations to mothers’ parenting stress at child age 14, with links to both maternal distress and child difficult behavior (although not dysfunctional interaction). In each case, higher stress experienced by one parent at child age 10 was predictive of higher parenting stress in the other parent at child age 14. Unfortunately, crossover effects within time periods were not assessed, as it would be important to demonstrate that one parent’s stress can influence the others’ experience of stress in the moment as well as years later. Identification of concurrent crossover effects creates some methodological challenges, and such research efforts remain for future studies. Nevertheless, crossover effects involving parenting stress have also been found in families of children with intellectual disabilities (see also Neece and Chan, Chap. 5 this volume), as Gerstein et al. (2009) reported that both mothers’ and fathers’ well-being and marital satisfaction influenced the others’ experience of parenting stress, and a positive father–child relationship helped to prevent rising parenting stress in mothers. It is this increasing attention to complex pathways of influence in longitudinal research that is providing more nuanced understandings of stress processes in families.

Mother Father Differences

The attention to coparenting processes highlights the importance of considering the potential differences between mothers and fathers with respect to parenting stress. Despite the emerging interest in coparenting, and the fact that “mothering” is no longer synonymous with “parenting” (Pleck, 2012), it is still the case that a disproportionate number of studies have examined parenting stress with respect to mothers only. Fathers, however, may differentially experience parenting stress, or the effects of the stress experienced may have different implications for fathers than it does for mothers. Some recent studies have included direct analyses of fathers’ parenting stress, comparing and contrasting the parenting experience for mothers and fathers. Some of those findings have been described briefly in previous sections, but the issues are addressed more fully below.

Although fathers’ parenting stress is now more prominently examined in research studies (Deater-Deckard, 2004), the evidence in support of differences or similarities is equivocal. Some studies find evidence of differences in the absolute levels of parenting stress between mothers and fathers (Delvecchio et al., 2015; Fang, Wang, & Xing, 2012; Skreden et al., 2012), while others do not (Crnic & Booth, 1991; Deater-Deckard & Scarr; 1996; Putnick et al., 2010; Solmeyer & Feinberg, 2011). When differences are found, it is typically mothers that report higher parenting stress. Nevertheless, the field seems no closer to resolving whether mother–father differences exist in the experience of parenting stress than it was a decade ago (Deater-Deckard, 2004). Sampling differences, the changing and evolving role of fathers, and varying conceptualizations of parenting stress are all likely contributors to the mixed findings that have emerged to date. Nevertheless, attempts to simply identify whether or not mothers and fathers differ in their reports of parenting stress are likely to be less meaningful than attempting to identify the conditions or contexts under which similarities and differences emerge.

Findings in studies of the relation between parenting stress and parenting self-efficacy between mothers and fathers have also been inconsistent, with some research identifying negative associations in mothers only (Reece & Harkless, 1998), and other studies finding these associations in fathers (Sevigny & Loutzenhiser, 2010). There are a number of explanations for these discrepancies, most of which have not been empirically tested. These include spillover of work-related stress to parenting stress, differences in working mothers and fathers as compared to stay-at-home parents, and developmental status of children, age of parents, etc. In order to better understand how parenting stress operates in mothers and fathers across various samples, these explanatory factors variables should be accounted for, or directly explored, in future studies.

The differential implications of parenting stress for parenting efficacy and the parent–child relationship have also been explored for mothers and fathers. Findings suggest that although mother–child and father–child relationships are unique, the effects of parenting stress on these relationships are not clearly understood. One suggestion is that father–child relationships are more vulnerable to parental stress than are mother–child relationships (Cummings et al., 2004). Opposing this suggestion however, Ponnet et al. (2013) found that associations between stress and parent–child relationships were equally strong for mothers and fathers. With respect to connections between parenting stress and specific parenting behaviors (e.g., engagement and warmth), contrasting relations are apparent. In studies of mothers, stress in the parenting role was associated with harsher, less responsive parenting behaviors, and less engagement with children, overall (e.g., Almeida, Wethington, & Chandler, 1999). Although the same is likely true for fathers, it has been demonstrated in only a few studies (e.g., Bronte-Tinkew, Horowitz, & Carrano, 2010). Importantly, Bronte-Tinkew et al. (2010) controlled for levels of maternal stress in their study, highlighting father’s experience of parenting stress as important, above and beyond mother’s experience. Continued examination of the complex interplay between parents’ experience of stress (crossover) within and across time and how such processes uniquely contribute to parenting and the parent–child relationship quality should prove important.

Given that fathers are increasingly more involved in the parenting of their children (Lamb, 2010) and are even provided parental leave in many states during the transition to parenthood, the effect of parenting stress for fathers will likely continue to evolve. Currently, inconsistencies are abundant, and a clear picture of mother–father differences in parenting stress, as well as their implications for parental efficacy, has not yet emerged.

Summary

The connections between parenting stress and parental efficacy are at once both straightforward and complex. There is consistent indication that parenting stress is associated with less parental efficacy, lower well-being, less positive interactive behavior, and less positive parenting and coparenting relations. However, the mediating and moderating mechanisms that underlie the connections between these factors are many and operate across pathways of influence that require attention to multidimensional perspectives on family functioning. Parenting stress may be a frequently studied determinant of parenting, and one for which there is a vast literature to digest and multiple methods to integrate, but our understanding remains far too basic to capture the complexity of the transactional processes that connect it to parental self-efficacy and family well-being.

Addressing the developmental and systemic complexities of parenting stress is the next major challenge for the field. Adopting more developmental and systemic perspectives for our work will encourage model building that conceptualizes parenting stress as “whole family” in its function and implication, and will better identify the stress processes that may differentiate developmental periods, care providers, and the multiple ways in parenting self-efficacy might be understood. Variations in measurement can be construed as a methodological challenge, or as a potential strength. Integrating divergent measurement models can be valuable in building frameworks that expand our understanding of parenting stress. No one approach is likely to capture the diversity of stressful processes relevant to parenting, but more multidimensional approaches can better illuminate the nature of this ubiquitous parental experience.

References

Abidin, R. R. (1992). The determinants of parenting behavior. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 21, 407–412.

Abidin, R. R. (1995). The parenting stress index professional manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Almeida, D. M., Wethington, E., & Chandler, A. L. (1999). Daily transmission of tensions between marital dyads and parent–child dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61(1), 49-61. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/10.2307/353882

Anthony, L. G., Anthony, B. J., Glanville, D. N., Naiman, D. Q., Waanders, C., & Shaffer, S. (2005). The relationships between parenting stress, parenting behaviour and preschoolers’ social competence and behaviour problems in the classroom. Infant and Child Development, 14(2), 133–154. doi:10.1002/icd.385

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman.

Baumrind, D. (1991). The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 11, 56–95.

Bronte-Tinkew, J., Horowitz, A., & Carrano, J. (2010). Aggravation and stress in parenting: Associations with coparenting and father engagement among resident fathers. Journal of Family Issues, 31(4), 525–555. doi:10.1177/0192513X09340147

Caldwell, B., & Bradley, R. (1984). Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment. Little Rock, AR.

Cassells, R.C. & Evans, G.W. (Chapter 2, this volume). Ethnic variation in poverty and parenting stress. In K. Deater-Deckard & R. Panneton (Eds.), Parental Stress and Child Development: Adaptive and Maladaptive Outcomes. NY: Springer.

Chang, Y., Fine, M. A., Ispa, J., Thornburg, K. R., Sharp, E., & Wolfenstein, M. (2004). Understanding parenting stress among young, low-income, african-american, first-time mothers. Early Education and Development, 15(3), 265–282. doi:10.1207/s15566935eed1503_2

Cheah, C. S. L., Leung, C. Y. Y., Tahseen, M., & Schultz, D. (2009). Authoritative parenting among immigrant Chinese mothers of preschoolers. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(3), 311–320. doi:10.1037/a0015076

Crockenberg, S., & Covey, S. L. (1991). Marital Conflict and Externalizing Behavior in Children. In D. Cicchetti, & S. L. Toth (Eds.), Rochester symposium on developmental psychopathology, 3, (pp. 235–260). Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Crnic, K. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (1990). Minor parenting stresses with young children. Child Development, 61, 1628–1637.

Crnic, K.A. & Booth, C. (1991). Mother and father perceptions of parenting daily hassles across early childhood. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53, 1042–1050.

Crnic, K. A., & Low, C. (2002). Everyday stresses and parenting. In M. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of Parenting (2nd ed., Vol. 4, pp. 243–268) Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Crnic, K., Gaze, C., & Hoffman, C. (2005). Cumulative parenting stress across the preschool period: Relations to maternal parenting and child behavior at age five. Infant and Child Development, 14, 117–132.

Cummings, E. M., Goeke-Morey, M., & Raymond, J. (2004). Fathers in Family Context: Effects of marital quality and marital conflict. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development, (4th ed., pp. 196–221). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Deater-Deckard, K. (1998). Parenting stress and child adjustment: Some old hypotheses and new questions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5(3), 314–332.

Deater-Deckard, K. (2004). Parenting stress. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Deater-Deckard, K., & Scarr, S. (1996). Parenting stress among dual-earner mothers and fathers: Are there gender differences? Journal of Family Psychology, 10(1), 45–59. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.10.1.45

Deater-Deckard, K., Pinkerton, R., & Scarr, S. (1996). Child care quality and children’s behavioral adjustment: A four-year longitudinal study. Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines, 37(8), 937–948.

Deater-Deckard, K., Smith, J., Ivy, L., & Petril, S. A. (2005). Differential perceptions of and feelings about sibling children: Implications for research on parenting stress. Infant and Child Development, 14(2), 211–225. doi:10.1002/icd.389

Delvecchio, E., Sciandra, A., Finos, L., Mazzeschi, C., & Di Riso, D. (2015). The role of co-parenting alliance as a mediator between trait anxiety, family system maladjustment, and parenting stress in a sample of non-clinical italian parents. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1–8.

Dohrenwend, B. P., & Shrout, P. E. (1985). “Hassles” in the conceptualization and measurement of life stress variables. American Psychologist, 40(7), 780–785. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/10.1037/0003-066X.40.7.780

Dunninga, M. J., & Giallo, R. (2012). Fatigue, parenting stress, self-efficacy and satisfaction in mothers of infants and young children. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 30(2), 145–159. doi:10.1080/02646838.2012.693910

Fang, H., Wang, M., & Xing, X. (2012). Relationship between parenting stress and harsh discipline in preschoolers’ parents. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 20(6), 835–838.

Feinberg, M. E. (2003). The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parenting: Science and Practice, 3(2), 95–131. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/10.1207/S15327922PAR0302_01

Feinberg, M. E., Kan, M. L., & Hetherington, E. M. (2007). The longitudinal influence of coparenting conflict on parental negativity and adolescent maladjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(3), 687–702. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00400.x

Feinberg, M. E., Jones, D. E., Kan, M. L., & Goslin, M. C. (2010). Effects of family foundations on parents and children: 3.5 years after baseline. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(5), 532–542. doi:10.1037/a0020837

Gable, S., Crnic, K., & Belsky, J. (1994). Coparenting within the family system: Influences on children’s development. Family Relations, 43, 380–386.

Gerstein, E., Crnic, K., Blacher, J., & Baker, B. (2009). Resilience and the course of daily parenting stress in families of young children with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities Research, 53, 981–997.

Gerstein, E. D., & Poehlmann-Tynan, J. (2015). Transactional processes in children born preterm: Influences of mother–child interactions and parenting stress. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(5), 777–787. doi:10.1037/fam0000119

Glatz, T., & Buchanan, C. M. (2015). Change and predictors of change in parental self-efficacy from early to middle adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 51(10), 1367–1379. doi:10.1037/dev0000035

Gray, P. H., Edwards, D. M., O’Callaghan, M. J., & Cuskelly, M. (2012). Parenting stress in mothers of preterm infants during early infancy. Early Human Development, 88, 45–49.

Harden, B. J., Denmark, N., Holmes, A., & Duchene, M. (2014). Detached parenting and toddler problem behavior in early head start families. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35(6), 529–543. doi:10.1002/imhj.21476

Jackson, A. P., & Huang, C. C. (2000). Parenting stress and behavior among single mothers of preschoolers: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Journal of Social Service Research, 26 (4), 29–42. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/10.1300/J079v26n04_02

Jones, T. L., & Prinz, R. J. (2005). Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(3), 341–363. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2004.12.004

Katz, L. F., & Gottman, J. M. (1996). Spillover effects of marital conflict: In search of parenting and coparenting mechanisms. In J. P. McHale, & P. A. Cowan (Eds.), Understanding how family-level dynamics affect children’s development: Studies of two-parent families (pp. 57–76, 112 Pages). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Lamb, M. E., (2010). How do fathers influence children’s development? Let me count the ways. The role of the father in child development (5th ed., pp. 1–26) Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Lamis, D. A., Wilson, C. K., Tarantino, N., Lansford, J. E., & Kaslow, N. J. (2014). Neighborhood disorder, spiritual well-being, and parenting stress in african american women. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(6), 769–778. doi:10.1037/a0036373

Leahy-Warren, P., & McCarthy, G. (2011). Maternal parental self-efficacy in the postpartum period. Midwifery, 27, 802–810. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2010.07.008

Mackler, J. S., Kelleher, R. T., Shanahan, L., Calkins, S. D., Keane, S. P., & O’Brien, M. (2015). Parenting stress, parental reactions, and externalizing behavior from ages 4 to 10. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(2), 388–406. doi:10.1111/jomf.12163

McQullian, M.E. & Bates, J.E. (Chapter 4, this volume). Parental stress and child development. In K. Deater-Deckard & R. Pannenton (Eds.), Parental Stress and Child Development: Adaptive and Maladaptive Outcomes. NY: Springer.

Merrifield, K. A., & Gamble, W. C. (2013). Associations among marital qualities, supportive and undermining coparenting, and parenting self-efficacy: Testing spillover and stress-buffering processes. Journal of Family Issues, 34(4), 510–533. doi:10.1177/0192513X12445561

Mills-Koonce, W., Appleyard, K., Barnett, M., Deng, M., Putallaz, M., & Cox, M. (2011). Adult attachment style and stress as risk factors for early maternal sensitivity and negativity. Infant Mental Health Journal, 32(3), 277–285. doi:10.1002/imhj.20296

Minuchin, S., Rosman, B.L., & Baker, L. (1978) Psychosomatic Families: Anorexia Nervosa in Context. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Neece, C.L. & Chan, N. (Chapter 5, this volume). The stress of parenting children with developmental disabilities. In K. Deater-Deckard & R. Panneton (Eds.), Parental Stress and Child Development: Adaptive and Maladaptive Outcomes. NY: Springer.

Nygren, M., Carstensen, J., Ludvigsson, J., & Frostell, A. S. (2012). Adult attachment and parenting stress among parents of toddlers. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 30(3), 289–302. doi:10.1080/02646838.2012.717264

O’Neil, J., Wilson, M. N., Shaw, D. S., & Dishion, T. J. (2009). The relationship between parental efficacy and depressive symptoms in a diverse sample of low income mothers. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18(6), 643–652. doi:10.1007/s10826-009-9265-y

Östberg, M., Hagekull, B., & Wettergren, S. (1997). A measure of parental stress in mothers with small children: Dimensionality, stability and validity. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 38(3), 199–208.

Pleck, J. H. (2012). Integrating father involvement in parenting research. Parenting: Science and Practice, 12(2-3), 243–253. doi:10.1080/15295192.2012.683365

Ponnet, K., Mortelmans, D., Wouters, E., Van Leeuwen, K., Bastaits, K., & Pasteels, I. (2013). Parenting stress and marital relationship as determinants of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting. Personal Relationships, 20(2), 259–276. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2012.01404.x

Pripp, A. H., Skreden, M., Skari, H., Malt, U., & Emblem, R. (2010). Underlying correlation structures of parental stress, general health and anxiety. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 51, 473–479.

Putnick, D. L., Bornstein, M. H., Hendricks, C., Painter, K. M., Suwalsky, J. T. D., & Collins, W. A. (2010). Stability, continuity, and similarity of parenting stress in european american mothers and fathers across their child’s transition to adolescence. Parenting: Science and Practice, 10(1), 60–77. doi:10.1080/15295190903014638

Reece, S.M. & Harkless, G. (1998). Self-Efficacy, Stress, and Parental Adaptation: Applications to the Care of Childbearing Families. Journal of Family Nursing, 4(2), 198–215. doi:10.1177/107484079800400206

Reitman, D., Currier, R. O., & Stickle, T. R. (2002). A critical evaluation of the parenting stress index-short form (PSI-SF) in a head start population. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31(3), 384–392. doi:10.1207/153744202760082649

Robinson, M., & Neece, C. L. (2015). Marital satisfaction, parental stress, and child behavior problems among parents of young children with developmental delays. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 8(1), 23–46. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/10.1080/19315864.2014.994247

Scheel, M. J., & Rieckmann, T. (1998). An empirically derived description of self-efficacy and empowerment for parents of children identified as psychologically disordered. American Journal of Family Therapy, 26(1), 15–27.

Schoppe-Sullivan, S., Settle, T., Lee, J., & Kamp Dush, C. M. (2016). Supportive coparenting relationships as a haven of psychological safety at the transition to parenthood. Research in Human Development, 13(1), 32–48. doi:10.1080/15427609.2016.1141281

Sevigny, P. R., & Loutzenhiser, L. (2010). Predictors of parenting self-efficacy in mothers and fathers of toddlers. Child: Care, Health and Development, 36(2), 179–189. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00980.x

Shea, S. E., & Coyne, L. W. (2011). Maternal dysphoric mood, stress, and parenting practices in mothers of head start preschoolers: The role of experiential avoidance. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 33(3), 231–247. doi:10.1080/07317107.2011.596004

Shumow, L., & Lomax, R. (2002). Parental efficacy: Predictor of parenting behavior and adolescent outcomes. Parenting, Science and Practice, 2, 127–150. doi:10.1207/S15327922PAR0202_03

Skreden, M., Skari, H., Malt, U. F., Pripp, A. H., Björk, M. D., Faugli, A., et al. (2012). Parenting stress and emotional wellbeing in mothers and fathers of preschool children. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 40(7), 596–604. doi:10.1177/1403494812460347

Solmeyer, A. R., & Feinberg, M. E. (2011). Mother and father adjustment during early parenthood: The roles of infant temperament and coparenting relationship quality. Infant Behavior & Development, 34(4), 504–514. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2011.07.006

Spinelli, M., Poehlmann, J., & Bolt, D. (2013). Predictors of parenting stress trajectories in premature infant–mother dyads. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(6), 873–883. doi:10.1037/a0034652

Teti, D. M., & Gelfand, D. M. (1991). Behavioral competence among mothers of infants in the first year: The mediational role of maternal self-efficacy. Child Development, 62, 918–929. doi:10.2307/1131143

Thomason, E., Volling, B. L., Flynn, H. A., McDonough, S. C., Marcus, S. M., Lopez, J. F., et al. (2014). Parenting stress and depressive symptoms in postpartum mothers: Bidirectional or unidirectional effects? Infant Behavior & Development, 37(3), 406–415. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2014.05.009

Weaver, C. M., Shaw, D. S., Dishion, T. J., & Wilson, M. N. (2008). Parenting self-efficacy and problem behavior in children at high risk for early conduct problems: The mediating role of maternal depression. Infant Behavior & Development, 31(4), 594–605. doi: http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/10.1016/j.infbeh.2008.07.006

Williford, A. P., Calkins, S. D., & Keane, S. P. (2007). Predicting change in parenting stress across early childhood: Child and maternal factors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35(2), 251–263. doi:10.1007/s10802-006-9082-3

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Crnic, K., Ross, E. (2017). Parenting Stress and Parental Efficacy. In: Deater-Deckard, K., Panneton, R. (eds) Parental Stress and Early Child Development. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55376-4_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55376-4_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-55374-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-55376-4

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)