Abstract

The author explores the specifics of learning/teaching Standard Chinese (SC) pronunciation, its goals and methods, within the broader context of L2 pronunciation learning/teaching. The ways in which research findings in Chinese phonetics and phonology might facilitate the acquisition of SC pronunciation by adult learners are investigated. An overview is provided of the textbooks and linguistic literature dealing with SC pronunciation. The usefulness of metalinguistic instruction is discussed. The following topics, among others, are addressed: the SC syllable structure, the third tone, acoustic correlates of stress, and the importance of unstressed function words.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

Pronunciation is one of the essential aspects of the acquisition of Chinese as a second language . The paper explores the specifics of learning/teaching Standard Chinese (SC) pronunciation, its goals and methods, within the broader context of L2 pronunciation learning/teaching . The ways in which research findings in Chinese phonetics and phonology might facilitate the acquisition of SC pronunciation by adult learners are investigated.

Note that the terms ‘language acquisition’ and ‘language learning’ are often used interchangeably, yet sometimes a distinction is made between the subconscious, naturalistic language acquisition, and conscious language learning. This chapter is concerned with the latter, as this is the approach adopted by most adults who aspire to master the Chinese language. Pedagogical aspects are given due attention, since attaining good L2 pronunciation requires guidance and should not be left to self-study.

2 Learning (SC) Pronunciation

2.1 The Specifics and Time Span

Although Chinese pronunciation is rather difficult (partly due to the tonal character of the language), this area tends to be overshadowed in SC teaching and learning by grammar, vocabulary and the enormously difficult Chinese script. On top of that, learning L2 pronunciation has specific features which are not always given due recognition.

While the new words, grammatical constructions and Chinese characters can be acquired and subsequently used in L2 performance one by one, in managing the sounds of connected speech all features need to be employed in one go – the very second the learner tries to say the most trivial sentence. Consider what the learner faces while attempting to say Zhè shì nǐ de ma? Footnote 1 这是你的吗? “Is it yours?” Quite a number of things, including: articulation of the ‘retroflex’ consonants zh (in zhè), sh (in shì), and of the apical vowel (in shì); the tonally weakened/neutralized syllable (in shì), the so called ‘half T3’ (in nǐ), the neutral tone following T3 (in nǐde), and specific intonation of the particle ma 吗 question. None of these features can be bypassed, if the sound form of the sentence is to be correct. In other words, one can easily avoid using a particular word or construction while speaking, but one can hardly avoid a particular difficult consonant, vowel, diphthong or tone , or skip word stress , sentence intonation , etc.

Pronunciation fundamentals are acquired at the very beginning of L2 studies, when the new phonological system of L2 becomes established in the learner’s mind. The beginner’s errors in speech production, if unattended, easily become fossilized due to the perpetuation of bad pronunciation habits, and the interlanguage phonology /phonetics may cease to develop. Teaching L2 pronunciation thus requires a deliberate teaching methodology, careful planning of the successive steps and well-thought-out coordination with other teaching objectives.

Pronunciation is commonly viewed as a skill acquired during the first year of L2 studies, while in the advanced stages of learning the attention to pronunciation usually decreases. Passable production of isolated words and the knowledge of orthography tend to be regarded as satisfactory outcomes. However, good L2 pronunciation amounts to more than tackling isolated words (although the early stages of learning are absolutely crucial, as noted above). Many things happen to the words when they enter fluent speech . Connected speech has a variety of features (prosodic features in particular), which fulfill important linguistic, communicative or pragmatic functions. L2 speech performance that lacks or distorts such features cannot be regarded as good performance. Yet these features are often left unnoticed by both teachers and learners, as well as by writers of teaching materials.

To sum up, acquiring good Chinese (or any L2) pronunciation is a long-term process, going beyond the span of the first few months. It may take even longer than the duration of the formal language classes. Thus, upon leaving the classroom, the students should be equipped with appropriate concepts and tools so they can continue to progress on their own.

2.2 The Goals and Realistic Prospects

Whereas some standard forms of native pronunciation (e.g. RP or GA for English) serve as a model in L2 studies, attaining them is not necessarily the goal. Hockett (1951: vii) writes: “A good pronunciation of a foreign language is one which will not draw the attention of a native speaker of that language away from what we are saying to the way in which we are saying it”. The degree to which learners aspire to native-like pronunciation varies. Most learners merely want to achieve a level that allows for effective communication. After they feel this objective has been reached, they prefer to invest their time in learning new vocabulary, phraseology, reading etc., instead of meticulously polishing up their pronunciation. Almost all adult L2 speakers thus retain an immediately recognizable foreign accent , which, however, usually does not stand in the way of successful communication. The lowest common denominator, intelligibility, is, however, undoubtedly shared by all L2 students. Even those learners with very modest goals probably do not wish to end up with a weird accent, which might seriously hinder communication with native speakers. Thus, due attention to pronunciation is an issue that concerns all groups of learners.

It is worth noting that outside the classroom learners of Chinese may largely expect to communicate with native speakers who may not be ready to cope with a heavy foreign accent (although they are accustomed to a variety of local Chinese accents). On the other hand, learners of English usually expect to communicate with other non-native speakers, using English as a lingua franca, and are happy to maintain their L1 accents (cf. the concept of ‘Lingua Franca Core’ for English).

What are the learner’s realistic prospects of success? Numerous linguists argue that pronunciation is a skill acquired subconsciously, and that the most important factors influencing the acquisition of L2 pronunciation (such as the age, motivation , goals and personal talent of the learner, the linguistic environment, the degree of exposure to native speakers, etc.) are largely beyond the control of the learner. The advocates of the ‘critical period hypothesis’ hold that it is impossible to achieve a full command of L2 beyond a certain age, while the critical age for acquiring native-like pronunciation is particularly low when compared to the acquisition of morphology or syntax. Proponents of these views regard practical exercises in L2 pronunciation or metalinguistic instruction on phonological rules and principles as ineffective.

Age, as well as a number of other uncontrollable factors, certainly affects overall success in SLA. Yet there are other important factors that are controllable. A fairly good approximation to native pronunciation is attainable for most learners if sufficient time is invested, proper guidance provided and efficient methods used.

Those learners who become aware of the close link between good pronunciation and effective communication may be motivated to go beyond the modest ambition of intelligibility. They may wish to devote more time to improving their pronunciation and take full advantage of the rich potential this tool provides. They can learn how to express various pragmatic meanings, attitudes , emotions and moods, they may sound rather more authentic and be able to enjoy L2 communication much more fully.

3 Teaching (SC) Pronunciation

3.1 The Explicit Teaching of Pronunciation

Pronunciation of Chinese (or any L2) cannot be automatically improved simply by increasing the amount of perception and production experience. Evidence of this are the cases of fluent speakers of Chinese who, even though they have lived in China for years, have a good command of Chinese grammar and have developed a native-like vocabulary, still find that their pronunciation remains quite deficient and far short of native speaker standards. They retain a strong foreign accent , substituting phonological structure and phonetic features from their L1 for Chinese ones. Thus, the prevailing opinion is that a natural acquisition of L2 pronunciation does not suffice, and some degree of explicit teaching is required. Whereas young children primarily rely on implicit learning mechanisms in language acquisition, adults benefit from focused teaching.

3.2 The Approaches and Methods

The relative importance of pronunciation teaching within the L2 teaching curriculum have fluctuated over the decades. Methods have been changing as well. In the traditional ‘Grammar-translation approach’ pronunciation was not the main area of concern, as teaching was largely based on written texts. A growing emphasis on spoken language proficiency brought about more interest in the significance of the explicit teaching of pronunciation. Its importance rose in the 1960s with the arrival of ‘Audiolingualism’ , based on behaviorist notions in SLA and supported by the development of recording technologies. Good pronunciation was of primary concern; error correction became a crucial issue. Drilling exercises and the ‘listen and repeat’ method were widely used. A major problem was that while students could accurately mimic discrete sounds out of context, they might not be able to integrate the learned skills in real communication. The communicative aspects of pronunciation, including suprasegmental (prosodic) features of connected speech , were largely left unnoticed.

Later on, attention to pronunciation teaching decreased as the ‘Communicative language teaching’ and ‘Natural approach’ rose to prominence in the 1970s and early 1980s. These approaches attempted to mirror the processes of natural language acquisition in the classroom setting. Emphasis was laid on developing communicative skills. The goals shifted from ‘perfect’ grammar and pronunciation to functional intelligibility and the increased self-confidence of students. Rule explanations, drilling and the explicit correction of errors were rarely employed. This approach resulted in a lack of pronunciation passages in textbooks . The outcome of the communicative approach was that L2 speakers often developed communicative abilities, oral fluency and self-confidence, but were left with numerous fossilized errors in their interlanguage .

The approach known as ‘Form-focused instruction’ (FFI) , which gained popularity from the 1990s onwards, recognized the importance of communicative principles in L2 teaching, yet allowed space for explicit instruction on linguistic forms and rules. It was argued that some features of the target language cannot be acquired without guidance. Sometimes, it is necessary to isolate particular forms or features “much as one might place a specimen under a microscope, so that the learners have an opportunity to perceive these features and understand their function” (Spada and Lightbown 2008: 186).

The last two decades have seen a surge of interest in teaching L2 pronunciation, supported by further advances in technology. Pronunciation is primarily viewed as an essential component of successful oral communication, as “another string in the communicative bow” (Jones 1997: 111). Particular recognition is given to the communicative importance of prosodic features of connected speech . The students are expected to take active responsibility for their own progress. Self-monitoring is considered an important part of the learning process. However, there is still much room for improvement in classroom activities. Tutatchnikova (1995: 95) observes for SC:

We can notice two main factors that [negatively] influence learning pronunciation at the beginning level: first, the large number of students in the class which impairs individual error correction analysis and correction feedback. Second, the classroom exercises focus on primary achieving fluency in performing an ever-increasing inventory of linguistic items and capacities within meaningful and culturally appropriate communication… [while] pronunciation is [inappropriately] considered to be improving gradually along with extensive practice of communication skills and due to home practice.

Speaking about methods of teaching L2 pronunciation, it is clear that traditional ‘listen and repeat’ approaches will always have an important role to play; pronunciation involves both cognitive and motor skills, and habit formation is thus an essential component of acquisition. Decades ago, Y. R. Chao (1925) wrote in his preface to A Phonograph Course:

To acquire a language means to make it of your own… This is best accomplished by hearing the same phrases and expressions over and over again, so that they will haunt you… you will find that the fluency gained through mechanical repetition is a great lubricant for the comprehension of what is spoken. (paragraph 6)

This claim is still valid nowadays. Thus, repetition and drilling cannot be removed from teaching.

Regarding teaching materials, an effort can be observed at introducing a communicative dimension of pronunciation into course book design. However, contrary to the current trends and findings of SLA investigation, many textbooks still retain the features of traditional audiolingual texts, largely relying on drilling decontextualized items. Metalinguistic instruction on pronunciation is often sketchy, imperfect and not in line with the findings of SLA research.

4 Metalinguistic Instruction

4.1 Yes or No?

Repetition exercises and speaking practice, no matter how extensive they are, may not suffice to improve a learner’s pronunciation. The problem is that the learner either may not hear the mistakes in his/her pronunciation, or does not know how to fix them. If the errors are to be removed, their competent diagnosis is needed, followed by the offer of a remedy. Clarifying the inner mechanism of pronunciation errors and providing proper guidance in correcting them is rarely achieved, though. Tutatchnikova (1995: 94) complains:

If a student’s response is reasonably prompt, semantically correct and appropriate culturally, then the student is usually encouraged, even if his/her pronunciation could be more accurate. There are no exercises… focused specifically on improving pronunciation skills in class. Consequently, students do not receive enough systematic feedback about their pronunciation. The correction they do receive is usually superficial, with errors being corrected [only] through multiple repetition… Deep pronunciation error correction , which implies an analysis of the reasons for the sound misproduction and an explanation of correct articulation , is usually not done.

It should be noted that pronunciation errors are more difficult to assess and correct than grammatical errors. While grammatical errors are mostly of the right-or-wrong type, pronunciation errors are, by nature, part of a continuum; articulation can be more or less close to the ideal pattern.

Besides the ad hoc correction and qualified ‘curing’ of pronunciation mistakes, the question arises as to whether the teaching curriculum should contain some degree of theoretical explication of the L2 phonological structure and phonetic phenomena. While the practice of focused instruction on L2 grammar rules has a long tradition, efforts to teach some underlying principles of pronunciation are much more recent.

In general, the extent to which metalinguistic knowledge contributes to a student becoming proficient in L2 continues to be a point of discussion. Focused rule instruction is sometimes viewed as useless or even detrimental (cf. ‘the Natural approach ’). Many teachers feel that if such instruction is overly abstract and complicated, it might discourage the learner. Some people say that extensive thinking about the rules (‘monitor overuse’) may impede speech production and decrease fluency. All these arguments may be true to some extent. However, various studies in SLA and cognitive psychology show that adult learners benefit from some level of a descriptive or analytic approach, as long as the knowledge is presented to them in an appropriate way. Jones (1997: 108) writes:

While rule teaching that is too complicated or elaborate (like all the varied rules governing intonation in discourse ) might overwhelm the monitor and thus be detrimental…, there seems to be no justification for denying learners linguistic information which may empower them to improve on their own.

Numerous linguists share the view that “while instruction may not directly alter learners’ underlying language systems, it can help them notice features in the input, making it more likely that they will acquire them.” (Spada and Lightbown 2008: 190). Rules can also help learners to monitor their own speech, i.e. to notice and correct pronunciation errors in their own output. In the long run, a certain level of phonological/phonetic awareness equips learners with concepts and devices for controlling their progress once they have finished their formal classroom education.

4.2 Integrating Research Findings into L2 Teaching: The Challenges

A basis for formulating metalinguistic rules and principles for the purposes of L2 teaching is provided by the findings of linguistic research. They may throw more light on the issues, correct various inaccuracies in pedagogical practice, challenge certain myths or conservative traditions, etc. They provide teachers with a powerful instrument for error correction . It becomes increasingly obvious that research findings should be consistently integrated into L2 pedagogy. This also applies to teaching Chinese (the trend is reflected, for example, in the founding of the CASLAR projectFootnote 2 in 2010 and in the main topic of the NACCL-27 conference Footnote 3 in 2015). My own experience (9 years of teaching courses of SC pronunciation at university level) has convinced me that some amount of metalinguistic sophistication may considerably support the development of good pronunciation skills. There are many challenges involved, however. Here are some of them:

-

There may be a lack of consensus on particular topics among linguists (there are, for example, different views on SC syllable structure , on the phonemic status of the palatal consonants j, q, x, etc.). However, L2 teaching must offer clear and unambiguous instructions. The accepted solution should always be consistent with other choices (note that in teaching SC, some choices are determined by the phonological system adopted in Pinyin , e.g. the two examples mentioned above).

-

Researchers, on the one hand , and language pedagogues or writers of teaching materials on the other, represent two distinct communities that usually do not cooperate much. Each group has its own objectives and approaches. Teachers may lack adequate training in phonetics/phonology to offer a more sophisticated treatment of the topics , while researchers may not be interested in pedagogical issues.

-

If learners are to absorb metalinguistic knowledge, it must be transformed into the language of practical teaching. Anyone who is carrying out such ‘translation’ activities must beware of making undue simplifications. It is difficult indeed to strip research results concerning a particular topic to the bare essentials and present them in an easy-to-learn manner that does not distort the substance.

-

Many learners are not particularly interested in language structure and theory. They may view learning pieces of phonetics and phonology as an abstract intellectual exercise that is boring, difficult and of little use. They should be persuaded that knowledge of the underlying principles of the Chinese sound system is not an end in itself , and may actually help them to communicate more effectively.

-

The question arises as to how to squeeze metalinguistic instruction on pronunciation into the teaching curriculum. In the first year of SC studies learners are overwhelmed by a large number of other tasks, including the time-consuming study of Chinese characters.

4.3 How to Go About Teaching the Rules

Teaching abstract rules and principles is rather dry. It should always be accompanied by abundant examples, direct application in speaking, and by the correction the errors . It may be useful to demonstrate a particular phenomenon by reference to a concrete example first , thus allowing the students to discover the patterns themselves (an inductive approach, ‘rule-discovery ’). For instance, students can be asked about the phonetic difference between two instances of qù 去 in the short dialogue below. They may be led to discover the features of an unstressed syllable in qù2 (such as short duration and tone weakening/neutralization ). Furthermore, they may infer that the cause of de-stressing is pragmatic : a word mentioned in a previous context, unless emphasized, loses its semantic importance:

– Nǐ qù ba. | 你去吧。 | qù1 |

– Wǒ bù qù! | 我不去! | qù2 |

Once the rule has been presented (or discovered), its application should be practiced. In doing so the learners’ attention must not be distracted by other tasks, because their processing capacity is limited. Thus, it is advisable to employ rather short units that focus on only one feature or principle at a time, while other features occurring in the unit have already been mastered (cf. ‘phonetic chunks’, yīnkuài 音块 outlined in Třísková in press). Integrating the learned features into communicative tasks and their automatization is the next step. Persistent, patient correction of individual errors is needed at all times.

Pinyin notation should be used as a major tool for presenting the example sentences and exercises, Chinese characters being only additional. Otherwise, most of the learner’s processing capacity is expended in deciphering the characters which are generally unrelated to the sounds. Of course, this does not mean to say that Pinyin provides students with precise instructions on how to pronounce words, cf. Sect. 6.1.

5 SC Pronunciation in Textbooks and Literature

5.1 General SC Language Textbooks

The initial stages of teaching Chinese pronunciation are taken up by elementary matters, such as Pinyin initials and finals, four tones , tone sandhi rules, reading of bù 不 and yī 一, neutral tone , and er-suffixed finals. In standard language textbooks these fundamentals are presented in the Introduction and/or successively in several of the initial lessons.

A widely used textbook series, Integrated Chinese (Liu et al. 2009: 1–11), may serve as an example. Pronunciation is treated in the chapter ‘Syllabic structure and pronunciation of Modern Standard Chinese’. The topics treated are: Initials; Finals; Tones; Neutral tone ; T3 sandhi . The explanations are rather brief and basic. No diagrams of the vocal organs showing the articulation of particular difficult sounds are presented. Some descriptions are misleading (e.g. comparing SC j to English j as in “jeep”, and SC q to English ch as in “cheese”). The authors themselves point out: “…the actual sounds [represented by Pinyin letters] can be very different from their English counterparts.” They continue:

Over time, you will acquire a better appreciation of the finer details of Chinese pronunciation. This chapter is designed to help you become aware of these distinctions, though attaining more native-sounding pronunciation will take time and effort through extensive listening and practice.

The authors obviously do not have any ambition to go into these “finer details” themselves.

A somewhat older textbook, Chinese Primer (Ch’en et al. [1989] following in the footsteps of Y. R. Chao’s Mandarin Primer), offers a similar picture, although the authors go into more detail and occasionally use sketches of the articulatory organs. The introductory section, ‘Foundation work’, is devoted to pronunciation (the blue volume ‘Lessons’, pp. 1–35) and contains the following chapters: The single tones ; Pinyin romanization; Tones in combination and tone sandhi ; Difficult sounds . It should be noted that unlike the previous textbook, the students are warned against drawing analogies with English consonants: “Take care to distinguish both palatals and retroflexes from English j, ch, sh, r…” (p. 8). Occasional mistakes can be found: “In pronouncing retroflexes, the tongue is curled back (retroflexed) until the tip touches the front part of the roof of the mouth” (p. 7). In fact, the tip of the tongue is not curled back (see Sect. 6.3, Fig. 1).

The BLCUFootnote 4 has published the Chinese-English series of textbooks Xin shiyong hanyu keben/New Practical Chinese Reader (Liu 2010). It addresses the following topics : Initials and finals; Tones; Third-tone sandhi ; Neutral tone ; Spelling rules; Tone sandhi of 不, 一; Retroflex endinɡ; A table of combinations of initials and finals in common speech. The explanations of particular phenomena are rather elementary and insufficient, e.g. the neutral tone is described like this (Vol. 1: 22): “In the common speech of modern Chinese, there are number of syllables which are unstressed and are pronounced in a ‘weak’ tone. This is known as the neutral tone and is indicated by the absence of a tone mark. For example 吗 ma, 呢 ne, 们 men.” There is no instruction whatsoever on how to pronounce the neutral tone . From Lesson 6 onwards, pronunciation passages virtually disappear. It should be noted that the predecessor of this textbook, Shiyong hanyu keben/Practical Chinese Reader (Liu et al. 1981), devoted much more space to pronunciation, dealing with it in almost every lesson up to Lesson 30, and then occasionally up to the very last Lesson 50. The topics included: Word stress ; Sense group stress ; Sentence tunes; Rhythm ; Pause ; Logical stress . These topics are entirely missing in the later edition.

An example of a textbook attempting to offer a more complete picture of SC pronunciation is another Chinese-English BLCU series of textbooks, Hanyu jiaocheng (Yang 1999). After expounding the fundamentals (up to lesson 6) subsequent lessons contain explication on: Word stress ; Sentence stress; Intonation ; Logical stress. Recognition of the importance of these topics , as well as a willingness to provide them with space, should be appreciated, although various inaccuracies can be found. For instance, “In a simple subject-predicate sentence… if the subject is a pronoun , it is stressed” (p. 92). The example given is Shéi qù? 谁去? In fact, the authors had in mind the interrogative pronouns, not all pronouns (e.g. the personal pronoun wǒ 我 in the sentences such as Bié kàn wǒ! 别看我! Wǒ è le. 我饿了。 is regularly unstressed). When addressing word stress , the cases where there is a lexical neutral tone on the second syllable (such as háizi 孩子) are not noted. Phrasal stress in expressions such as sān běn shū 三本书 is subsumed into ‘Word stress ’. Speaking of intonation , the authors write: “Normally, the rise is used in interrogative sentences, while the fall is used for indicative sentences” (p. 93). This statement is skewed, since high final pitch concerns only some types of question (as the authors themselves later note). Some sort of general introduction to the topic (e.g. intonation) may be missing (What is intonation? What functions does it have?). Example sentences are given solely in characters (not in Pinyin ), etc.

To sum up, standard textbooks nowadays usually do not go beyond the basics. The focus is on practicing isolated tonal syllables , minimal pairs such as zhū-chū, and disyllabic words or word combinations such as qìchē, bàba, hěn xiǎo or bù qù. The major goal is to attain correct pronunciation of decontextualized words. It is tacitly assumed that the rest will be coped with by the learners themselves, by means of the “extensive listening and practice” recommended in Liu et al. (2009). However, this may not suffice, as noted above. Students are largely unprepared for tone variation in connected speech caused by stress /non-stress , intonation , a fast speech rate , emotions , a casual style of speech , etc. They often feel confused when being confronted with such variations, having no clue as to what is happening. Kratochvil (1968: 35) rightly points out:

[The Chinese tones] often cause frustration to students of MSC who are puzzled by the vast difference between the common theoretical description and the appearance of tones in neatly arranged combination patterns at one hand, and the phonetic reality of tones in live speech on the other.

Clearly, fundamental instruction on the level of isolated words should be followed by instruction on the higher linguistic levels (the phrase, the sentence, discourse ) involving communicative and pragmatic aspects of pronunciation. I take the liberty of using a metaphor overheard at a conference devoted to teaching English pronunciation (EPIP 2015, Prague):

Isolated words are like plants in a greenhouse – each one is neatly separated in its flowerpot and given meticulous care. Real communication is a jungle: speech is full of irregularities, errors, contractions, it may be very fast, fragmentary, the words are not separated from each other in speech signal, they may be reduced, swallowed etc. The road from the greenhouse to the jungle should lead through the garden with flowerbeds where the flowers grow naturally and next to each other, yet under control.

It appears that writing an effective introduction to SC pronunciation covering all structural levels for a general language textbook requires an author to be at least partly qualified in SC phonology and phonetics , and to have some insight into research literature, no matter how brief and terse such treatment would be.

5.2 Books Focused on SC Pronunciation

Let us look at the titles written in English first. The number of textbooks and teaching materials concerned solely with SC pronunciation is quite small. Huang (1969) is limited to simple descriptions of the articulation of particular consonants, vowels, diphthongs , and triphthongs, accompanied by sketches of the vocal organs, adding an explanation of tones (note that Huang uses the IPA symbols in comparison with various romanization systems, including Pinyin ). Dow (1972) addresses the topic more comprehensively (up to stress , but not intonation ), although the main emphasis is on the description of vowels and consonants (he does not work with Pinyin, using the IPA instead; sketches of the position of articulatory organs are presented for the consonants). More recently, Chin (2006) does not go beyond an isolated tonal syllable (he uses Pinyin). The old textbook by Hockett (1951), which provided exercises to improve SC pronunciation, should be mentioned (it is concerned mainly with initials, finals and tones; note that Hockett uses Yale transcription). As such, it contains a deep and still quite valid introduction to Chinese pronunciation.

Knowledgeable, yet accessible advice on SC pronunciation can be found in a number of English monographs devoted to the Chinese language as a whole, containing substantial chapters on SC phonetics/phonology , e.g. Chao (1968), Kratochvil (1968) and Norman (1988). Simple overviews are provided, for example, in Kane (2006) and Sun (2006).

There is a whole range of Chinese textbooks that only address the issue of SC pronunciation (they are usually called yǔyīn jiāochéng 语音教程). Yet, most of them tend to be rather elementary. For reasons of space, these will not be mentioned here.

A deep level introduction to SC pronunciation can be found in the textbook Hanyu yuyin jiaocheng (Cao 2002), published as part of the BLCU Hanyu jiaocheng series. The explications are competent and knowledgeable (the author is a trained phonetician; he employs the IPA). The sections are:

-

Introduction (the fundamentals of acoustics and articulatory phonetics)

-

The IPA; articulation of vowels and consonants; the phonemes and allophones

-

The SC syllable (the initials, the finals, the tones , SC syllable structure )

-

Sound changes in fluent speech (assimilation, dissimilation, er-suffixation, tone sandhi )

-

Prosody (stress , rhythm, intonation )

It can be stated that Cao Wen’s book outlines the basic ground plan for teaching SC phonetics/phonology within the Pinyin framework. Another example of a fairly detailed pronunciation textbook that is worth mentioning is Duiwai hanyu yuyin (Zeng 2008; the author also employs the IPA). Very useful insights into particular challenges when learning SC pronunciation are offered in Zhu (1997) and Cao (2010).

Besides the textbooks, several monographs published in the P.R.C. exist, which offer qualified descriptions of SC sound structure within the Pinyin framework, e.g. Xiandai hanyu yuyin gaiyao (Wu 1992), Putonghua yuyin changshi (Xu 1999), and Yuyinxue jiaocheng by Lin and Wang (2003, revised edition Wang and Wang 2013).

Unfortunately, the above-mentioned books are written in Chinese, thus they are not directly accessible to learners of Chinese and a wider readership. It is to be regretted that no English translations of such textbooks or monographs are available.

5.3 Research Literature

There are a few more or less recent monographs written in English that are devoted to a theoretical analysis of SC phonology /phonetics within a particular conceptual framework. Duanmu (2002) is mainly interested in phonology. He employs feature geometry in his analysis of segments (i.e. vowels and consonants); he uses Optimality Theory to study the syllable , and applies metrical phonology when addressing stress . The phonological framework of Lin Yen-Hwei (Lin 2007) belongs to the family of constraint-based approaches. Together with phonological analysis, she is interested in phonetic aspects and processes. She (unlike Duanmu) deals with intonation , although only briefly. These two titles appear to be the only comprehensive ones in existence.

Other studies deal with particular aspects of SC phonology . For instance, Cheng (1973) offers a generative analysis of the isolated syllable (including tone ). Li (1999) is concerned with the segmental syllable (without tone); his analysis is diachronically motivated. Shen (1989) explores sentence intonation and its interplay with tones and stress . Tseng (1990) studies the acoustic correlates of tones and the relationship between tone and intonation. Finally, there is a vast array of articles, papers and book chapters that touch upon particular narrow topics of SC phonology /phonetics, both in English and in Chinese.

As these studies are rather difficult to comprehend and, by and large, incompatible with the Pinyin framework (e.g. they mostly do not accept the initial-final analysis of the SC syllable ), they cannot be directly used in the practical teaching/learning of SC pronunciation . However, they can serve as a valuable source of knowledge and inspiration for writers of teaching materials, teachers and rather advanced students, broadening their linguistic horizons and offering interesting alternative viewpoints.

6 The Topics in Teaching/Learning SC Pronunciation

In this section I will attempt to demonstrate how the insights of linguistic research can help in teaching and learning SC pronunciation. Only a number of topics, belonging to the pedagogically most important ones, can be the subject of comments in the following review. Many interesting issues have had to be skipped: the pronunciation of various difficult segments (e.g. variable source of aspiration friction in the aspirated consonants), the question of the zero initial, the classification of the finals (including the centuries old sì hū 四呼 concept), tone sandhi (a favorite topic for phonologists), the neutral tone (the ultimate case of stress loss), word accentuation (a frequent subject of research into SC stress), junctures (their acoustic cues, distribution and importance for easing speech perception), utilizing computer software for acoustic speech analysis (such as Praat ) in acquiring pronunciation, etc.

6.1 What Is Hanyu Pinyin?

Teaching SC pronunciation is nowadays based on the Pinyin alphabet. Pinyin notation is often expected to provide guidance on the acceptable pronunciation of words, and, in turn, is criticized for not being able to fulfill this task properly. However, there is a misunderstanding (as e.g. Zhu [Zhu 1997: 138] points out). In fact, Pinyin should not be regarded as a phonetic transcription (such as the IPA ). It is a kind of orthographic system in its own right, which fulfills numerous functions. It was originally developed by the Chinese for the Chinese, not for L2 learners. Although its spelling is not as blatantly irregular as English orthography and reflects the actual sounds much more faithfully, its reading must still be learned. The basic framework of Pinyin is built up phonologically, utilizing a complementary distribution of sounds and largely neglecting the allophones. Furthermore, it takes into account factors such as economy or visual clarity, assigns unexpected sound values to some of the letters (such as q, x, zh), etc. Thus, Pinyin serves only as a very rough guide to SC pronunciation, as a sort of scaffolding that helps to build up the learner’s competence in pronunciation. “You can learn nothing at all from the transcription itself, neither how to pronounce Chinese nor anything else. The transcription stands as a perfectly meaningless jumble of letters to you until you have learned , in terms of pronunciation and hearing, what it is that is being represented by it.” These words of Hockett (1951: xvii) actually concern Yale transcription, yet are equally valid for Hanyu Pinyin. It is the task of both pedagogues and textbook writers to make this point clear.

6.2 Fundamentals of Phonology

When beginning to learn L2 pronunciation, the learner has to forget the familiar phonological system of L1 and build up a new ‘phonological sieve ’ for the L2, with its different parameters for filtering sounds.Footnote 5 The new sieve allows him/her to distinguish between those sound features of L2 that are essential (distinctive) for particular phonemic categories, and those which are mere within-category phonetic variations.

Acquiring the new phonological system may be aided by instruction on the useful general notions. For instance, the above-mentioned notion of distinctive features may help in understanding that the same phonetic feature (e.g. voicing) may be utilized differently in SC and in the student’s L1. For instance, voicing is not distinctive in SC, while it is distinctive in Czech; aspiration is distinctive in SC, while it is not distinctive in English. The notion of phonemes and allophones may help in gaining an understanding of why the same Pinyin letter can represent several rather different sounds or phonemes (e.g. the letter ‘i’ is read as [i] in lǐ 里, as [j] in xià 下, as [ɪ] in lái 来, as [ɿ], [ʅ] in zì 字, shì 是). The notion of complementary distribution may help in understanding why ü, in syllables such as ju, qu, xu, does not require an umlaut in orthography, while in nü, lü it does (the letter ‘u’ represents two different phonemes: /u/ and /ü/). See, for example, Lin (2007: 138; 2014), Duanmu (2002: 19).

SC sound structure is acquired by means of Pinyin phonology. The learners thus naturally tend to view Pinyin as ‘God’s truth’. However, they should be briefly reminded that there are still many other phonological interpretations of SC. This sort of awareness may help them to view the phonological system (and, by extension, phonetic reality) in a less rigid way.

6.3 Articulatory Phonetics , the IPA

While acquiring SC consonants and vowels, students have to learn new articulations . Notably, they should avoid replacing particular SC sounds by similar, yet not identical L1 sounds with which they are familiar. For instance, the SC consonant r is regularly pronounced as an unrounded postalveolar approximant [ɻ], or less frequently, as a fricative [ʐ]. Yet native speakers of English often pronounce it as [ɻ] with lip rounding, French learners as a uvular fricative [ʁ], Italian learners as an alveolar trill [r], etc. Nuances of vowel articulation are frequently neglected, too (e.g. the difference between front [a] and back [ɑ]). Experimentally based phonetic descriptions clarifying the articulatory/acoustic features may promote the correct learning of new sounds. This inevitably involves the need to explain various places of articulation (alveolar, palatal…) and manners of articulation (stops, fricatives, affricates, approximants…) for the consonants. The student should know terms such as voiced vs. voiceless, aspirated vs. unaspirated, lax (lenis) vs. tense (fortis), co-articulation, secondary articulation etc. As regards the vowels, there are terms such as front–back, close/high–open/low, unrounded–rounded, vowel centralization, devoicing, nasalization, retroflexion, etc. This seemingly dry knowledge is highly practical because it helps learners to realize the differences between L1 and L2 sounds and attain control over the fine phonetic details of articulation . At the same time, it provides the teacher with an efficient instrument for error correction .

The usage of (good quality) diagrams of the articulatory organs (i.e. their sagittal sections) and of palatograms is highly advisable in teaching, especially with difficult sounds. The diagrams may, for example, clarify the point that SC ‘retroflex’ consonants zh, ch, sh, r are not in fact retroflexed at all, although they are commonly called so and transcribed by the retroflex IPA symbols, with a ‘hook’:

Palatograms are useful, too. They may, for example, demonstrate that the so called SC ‘palatal’ consonants j, q, x are in fact alveolopalatal (see Fig. 2).

The previously mentioned knowledge about articulatory mechanisms is a necessary prerequisite for teaching the International Phonetic Alphabet (see Fig. 3) . Although neither teachers nor students are usually much fond of it, the basic command of the IPA (or at least a passive knowledge of the symbols which are used for SC sounds) is desirable. It allows impressionistic descriptions of sounds to be replaced by rather exact notations.Footnote 6 See e.g. Lee and Zee (2003, 2014).

6.4 Syllable Structure

The views of linguists in relation to SC syllable structure vary (cf. traditional Initial-Final model vs. modern Onset-Rime model described in Lin 2007: 106). The key question is the position of the prenuclear glide (the ‘medial ’) within the syllable structure: is it more closely related to the consonantal onset (the ‘initial’), or to the vocalic nucleus (the ‘main vowel’) belonging to the syllable rime? Another question relates to which syllable constituents are obligatory, and which are optional (e.g. is a vowel an obligatory constituent of the SC syllable?).

Pinyin phonology adopts the traditional Initial-Final model. The textbooks introduce the SC syllable as a combination of initial, final and tone . The finals are usually not the subject of further analysis in the textbooks, despite the fact that they may be complex forms containing up to 3 constituents (medial , main vowel , ending ) with non-linear mutual relationships.Footnote 7 These relationships are clarified in the hierarchical scheme provided in Fig. 4. (cf. Lin 2007: 107; Cheng 1973: 11).

Structure of SC syllable (traditional analysis) (Adopted from Triskova 2012: 39)

Each of the constituents at the lowest level has its own specific articulatory features (latent in Pinyin notation, of course). These are well noted in the phonetic literature, but commonly left unexplained by teachers and textbooks (cf. Třísková 2011).

-

The medials i, u, ü (‘semivowels’, glides) are pronounced as tense, short approximants (i.e. consonants) [j], [w], [ɥ] respectively (xià 下 [ɕja], huán 环 [hwan], lüè 略 [lɥɛ]).

-

The main vowels a, e, o, i, u, ü are usually pronounced as full vowels.

-

The endings (terminals) are pronounced in a lax manner, their articulation is weakened, the articulatory target is undershot: the vocalic endings i, u are pronounced as [ɪ], [ʊ] (mài 卖 [maɪ], dào 道 [tɑʊ]); the nasal endings n, ng often have an imperfect or even missing closure (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 Missing closure in casual pronunciation of the ending -n (Ohnesorg and Švarný 1955, Fig. 19)

Syllable scheme (let alone the analysis of its components) can hardly be found at all in textbooks . However, deeper insights into syllable structure are rather useful. Why? Because this can help the learner to overcome various mistakes in the pronunciation of finals.

First, the difference between two types of diphthongs can be clarified (see Sect. 6.5).

Second, in casual speech, terminal nasals -n, -ng are often pronounced with incomplete or missing closure (see Fig. 5). Such “sloppy” pronunciation can be conveniently explained by reference to the regular tendency to a weakened articulation that is shared by all endings (n, ng, i, u).

Third, the syllable scheme allows for an understanding of the various segmental processes occurring within a syllable (cf. Lin 2007: 137). In particular, the lower right part of the scheme shows the close link between the main vowel and the ending (forming the yùn component, subfinal together). This tight connection explains the assimilation processes that happen within yùn. For instance , in syllables such as bān 班 [pan] the vowel /a/ is pronounced as front [a], being assimilated to the front nasal ending [n], while in syllables such as bāng 帮 [pɑŋ] the vowel /a/ is pronounced as back [ɑ], being assimilated to the back nasal ending [ŋ]. The tight connection between the main vowel and the ending may occasionally result in the phonetic fusion of both constituents, e.g. bāng 帮 [pɑŋ] may be pronounced as [pɑ̃], or mǎn 满 [man] as [mã], as reflected in Fig. 5.

6.5 Two Types of Diphthongs

A deeper insight into the SC syllable structure brings with it considerable advantage: it allows us to explain the difference between falling and rising diphthongs. While many languages lack diphthongs entirely, SC is very rich in this respect. Pinyin phonology establishes four falling diphthongs (/ai/, /ei/, au/, /ou/), five rising diphthongs (/ia/, /ie/, /ua/, /uo/, /üe/), plus four triphthongs (/iau/, /iou/, /uai/, /uei/).Footnote 8

The pronunciation of each type of diphthong is quite different. This fact is of course not reflected in Pinyin notation (cf. -ai, -ia). Falling diphthongs comprise a main vowel and (vocalic) ending, while rising diphthongs comprise a medial and main vowel. The difference in their pronunciation is clear from what has been stated about the articulatory properties of particular syllable constituents (see Sect. 6.4). For instance, xià 下 is pronounced as [ɕja] (the medial /i/ is realized as an approximant [j]), while mài 卖 is pronounced as [maɪ] (the ending /i/ is realized as a lax, centralized [ɪ]).

Specific features of the two types of diphthongs generally remain unnoticed by teachers and textbooks . Yet an effective teaching of their pronunciation , together with an emphasis on the tautosyllabicity of their components (i.e. strictly pronouncing the components of a diphthong as well as a triphthong within a single syllable) helps prevent one common mistake – tearing a syllable into two parts: *[ɕi.ja], *[ma.ji], *[ta.ʊ].

6.6 The Third Tone

The tones represent a greatly feared aspect of Chinese pronunciation. Y. R. Chao writes in his preface to A Phonograph Course (Chao 1925):

The Chinese tones are reputed to be the most difficult part of the language. It is so only because Europeans cannot be convinced realistically enough of the fact that modulation of pitch is as much an etymological element of the word as consonants and vowels are, and not merely an incidental accompaniment. (paragraph 2)

The pitch contours of SC tones are traditionally represented by a rectangular diagram employing Y. R. Chao’s five-point scale (Chao 1968, p. 25). The description of tones is based on the shapes of citation tones (T1 = 55, T2 = 35, T3 = 214, T4 = 51). Such a tone diagram can be found in every textbook . Examples coming from three different textbooks are reproduced in Fig. 6.

T3 is commonly portrayed as a “spiky” contour with a conspicuous final rise (214), see the first diagram in Fig. 6. The rise takes up more than half of syllable duration . At first glance it seems to be an essential, obligatory part of T3. The description of T3 as a ‘dipping tone 214’ is presented in an absolute majority of textbooks . However, the final rise is not obligatory. First, it may only occur in prepausal positions . Second, it is not obligatory even in prepausal positions : it may be entirely missing here (211). Third, if the rise does occur, it can be rather inconspicuous (213 or 212). To sum up , the final rise may be attributed to sentence intonation , focus , emotions, etc. Regarding the mild initial fall, it may be attributed to articulatory constraints (cf. Duanmu 2002: 220). Thus, most phonologists treat T3 as an underlyingly ‘low’ tone (L or LL in feature analysis) with an optional final rise that occurs in sentence- or phrase-final position. In other words, the rise is not viewed as a part of the underlying form of T3. The 214 realization is just one of the allotones , surface variations of T3. Such analysis is accepted in Kratochvil (1968: 35), Shih (1988: 83), Zhu (1997: 186), Yip (2002: 180), etc. This solution is also reflected in the last diagram in Fig. 6 (the final rise is rendered as optional). The ‘low’ interpretation of T3 agrees with speech facts: the majority of T3 surface realizations in connected speech are without the final rise.

T3 is viewed as the most difficult tone . The reason for this seemingly rests in the considerable variability of its surface forms (falling-rising before a pause; low before T1, T2, T4, T0; changed into T2 before another T3), which is traditionally explained by virtue of T3 sandhi rules (cf., for example, Lin 2007: 197, 204). Sandhi rules need to be applied in the majority of occurrences of T3 in speech. Some linguists, including the author of this paper, suggest that the student’s difficulty with T3 may not be due to the inherent difficulty of T3, but to its phonological interpretation as 214. The 214 phonological tradition and ‘half-third tone ’ (半三声) sandhi rule do not actually bring about any benefits in L2 teaching. This interpretation only increases the difficulty of T3 mental processing and causes its confusion with T2 (both tones comprise some kind of rise). The term ‘half-third tone’ rather improperly suggests that the 21 or 211 form (which is the most frequent form of T3 in speech) is something incomplete and truncated. I would argue that if the analysis of T3 as a low tone is introduced into SC tone teaching, it would greatly simplify things. Such an analysis is advocated by a number of Chinese linguists and pedagogues, such as Lin (2001b: 213), Cao (2002: 94) and Yu (2004).

6.7 Attention to Disyllables

As mentioned above, descriptions of the four tones in SC pedagogy conventions are based on the citation forms of tones. Due to a wide range of factors (such as the influence of adjacent tones, stress , intonation , speech style, speech tempo, emotions, etc.) the shapes of citation tones undergo considerable variation in connected speech. This may occasionally be drastic in rapid casual speech , where quite a number of tones may be reduced or deleted. Students need to be prepared to cope with this variability. The first step in this direction is to give increased attention to disyllables (instead of monosyllables) in tone teaching. It is well known that disyllabic tone combinations are not simply a plain sum of two tone contours as pronounced in isolation. One of the reasons for this is that there are physiological constraints that require some time for the transition of pitch between two adjacent tones; both tones coalesce into a single contour . Disyllables are then perceived and produced as wholes, not as combinations of two discrete components.

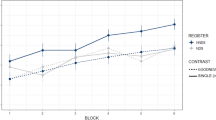

The mutual influence of two adjacent tones and changes in their F0 (fundamental frequency) contours are analyzed in Xu (1997) (also cf. Třísková 2001). He observes the carry-over effects (the effects of the preceding tone on the following tone), and anticipatory effects (the effects of the following tone on the preceding tone). The magnitude of the former is very noticeable, as can be seen in Fig. 7. In each panel, the tone of the first syllable varies between T1 (H = high), T2 (R = rising), T3 (L = low) and T4 (F = falling); the tone of the second syllable remains constant. Obviously, the ending F0 of the first syllable virtually determines the onset F0 of the second syllable:

Carry-over effects; in each panel the tone of the first syllable varies, while the tone of the second syllable remains constant (Xu 1997)

There are 16 disyllabic tone combinations . Diagrams of the pitch contours of these 16 combinations, based on instrumentally obtained data, would be very useful in tone teaching.

Regarding the four combinations with T0 in the second position (T1 + T0, T2 + T0, T3 + T0, T4 + T0), acoustic measurements show that T0, although very short, is realized as a kind of contour. Yet, for the purposes of teaching pronunciation, T0 can be conveniently represented as a ‘point’ whose position is decided by the preceding tone. T0 is relatively low after T1, T2, T4, while it is high after T3 (cf. e.g. Chao 1968: 36). Memorizing 16 + 4 concrete disyllabic ‘model words’ can be quite helpful, e.g. T3 + T1: lǎoshī, T4 + T0: bàba.

6.8 Acoustic Correlates of Stress/Non-stress

Chinese stress is a complex and rather controversial issue and has been addressed in the research of numerous linguists (e.g. Duanmu 2001). At the same time, stress has many pedagogically relevant aspects. One of them is the provision of advice on the distribution of stressed and unstressed syllables /words in speech (see Sect. 6.9). Another relates to the concrete instructions that can be given to a learner about what they should do with a syllable in order to make it sound stressed or unstressed. In textbooks , the instructions on this topic are usually limited, wrong or completely missing. For instance, in Liu Xun (Liu 2010: 50) we find the following sentence alongside the first mention of stress: “In a disyllabic or multisyllabic Chinese word there is usually one syllable that is stressed. This syllable is called the stressed syllable.” There is no advice whatsoever on how to make a syllable sound stressed. The reader would probably wrongly infer that it should be pronounced more loudly.

Fortunately, unlike with other aspects of SC stress, there is a broad consensus in the literature on its phonetic cues, which is supported by instrumental data. The linguists (e.g. Shen 1989: 59; Lin 2001a: 140; Lin 2007: 224; Shih 1988: 93) agree that in SC, stress/non-stress are phonetically manifested by:

-

the manipulation of syllable duration (long/short)

-

the manipulation of vertical pitch range (expanded/compressed)

-

the manipulation of loudness (as a secondary feature)

-

segmental reductions in the unstressed syllables

In other words, stressed syllables are phonetically enhanced in relation to all parameters: their duration is longer, their pitch range is wider, and they are generally somewhat louder. Their consonants and vowels are fully articulated. On the other hand, unstressed syllables are shorter, have compressed pitch range, and may be less loud. Articulation of their consonants and vowels tends to be weakened. Due to pitch range compression and shortened duration, tone contour in unstressed syllables becomes less distinct; it may be even completely deleted (neutralized ). Tone reduction is illustrated in Fig. 8; cf. Chao’s metaphor of “stretching the tone graph on an elastic background”, reminding us that phonetic reality is a continuum (Chao 1968: 35).

Scale of tone reduction: emphasized tonal syllable , ‘normally stressed’ tonal syllable, tonally neutralized syllable (tone diagram comes from Cao 2002: 94)

Stress/non stress production ‘know-how’ should be provided in textbooks , as the instincts of students regarding stress are significantly conditioned by interference from their L1 (as is well-known, stress can be manifested by different means in different languages, although it always comprises some combination of the following suprasegmental features : pitch , duration , and loudness). Due to the complex interplay between stress and tone , the proper control of the phonetic parameters of SC stress/non-stress is a hard-to-learn skill, which should be sufficiently practiced. The neutral tone (i.e. the complete loss of stress) and unstressed syllables are discussed, for example, in Liang (2003), Peng et al. (2005: 236), Lee and Zee (2014: 375).

It should be noted that the reduction of the unstressed syllables, observed especially in fast colloquial speech (particularly in Beijing Mandarin), is recognized as a feature of so-called ‘stress-timed languages’ such as English and Russian. Although the concept of ‘stress-timed languages’/‘syllable-timed languages ’ is hard to verify instrumentally, and often viewed as doubtful , it has proven its usefulness in L2 teaching. This may hold true for teaching everyday colloquial (‘stress-timed’?) SC, too (cf. Lin and Wang 2007).

6.9 Unstressed Function Words

Cross-linguistically, function words, such as prepositions, conjunctions, auxiliary verbs, personal pronouns, articles etc. are high-frequency, typically monosyllabic items. Their meaning is largely or entirely grammatical. They tend to be unstressed in speech, being tightly attached to a neighboring word as clitics (cf. Spencer and Luís 2012). In some languages, the pronunciation of function words displays a severe reduction. This is typically the case in English. It namely concerns ‘words with weak forms’, such as you, the, from, in, of, and… (e.g. and [ænd] becomes reduced to [ən], [n̩], cf. Roach 1996: 102).

SC has a number of toneless function words which always behave as unstressed clitics : sentence-final particles such as ma 吗, le 了, structural particles de 的, de 得, de 地, and aspect particles le 了, zhe 着, guo 过. In addition, a group of monosyllabic tonal function words may be established in colloquial everyday SC, which displays similar features as English ‘words with weak forms ’. A new term is coined for them: ‘the cliticoids’ (Třísková 2016: 134). The group of cliticoids comprises monosyllabic prepositions, postpositions, conjunctions, classifiers, personal pronouns, modal verbs, some other verbs (shì 是, zài 在, existential yǒu 有), and some adverbs (e.g. hěn 很, dōu 都, jiù 就). Unless emphasized or pronounced in isolation, they are regularly unstressed in speech. Their duration is shortened, their tone becomes weakened or deleted, and their vowels and consonants tend to suffer from segmental erosion . Acquiring the unstressed, reduced forms of these high-frequency words and their proper usage in speech may considerably improve a learner’s performance (cf. Tao 2015) as well as speech perception.

There are yet other cases of words or morphemes which are regularly pronounced as unstressed in speech, although they carry a lexical tone, e.g. the negative adverb bù 不 in A-not-A questions (Lái bu lái? 来不来?), the second syllable in reduplicated verbs (kànkan 看看), directional complements (chūqu 出去) etc. (cf. Zeng 2008: 102). These cases also require the attention of both teachers and learners (cf. Třísková 2016: 128).

6.10 Sentence Intonation

Acquiring native-like intonation patterns belongs to the most difficult set of tasks in SLA. The intonation component is one of the strongest indicators of a foreign accent . The main parameter of intonation is pitch (F0 variations in acoustic terms). On top of that, pitch variations are also used for cueing tone and stress in Chinese. This makes the picture rather complex. Due to this complexity, intonation tends to be neglected in SC teaching, although it carries important grammatical, pragmatic and attitudinal information.

The details of the complex interplay of intonation , tone and stress are examined in experimental studies (e.g. Shih 1988; Jiang 2010; Xu 2015). In SC teaching, however, this complexity needs to be simplified. Students mainly need to be presented with several fundamental intonation patterns , supplemented by the information that the basic distinctive features of tones such as rise or fall remain unharmed (Chao [Chao 1968: 39] speaks of “small ripples riding on large waves”). An example of such a simplification is Shen Xiaonan’s model (Shen 1989) (see Fig. 9).

Three basic intonational tunes of SC (Shen 1989: 26)

According to Shen, Tune I occurs only in statements. Tune III comprises A-not-A questions , alternative questions and Who-questions. Tune II is reserved for particle questions and unmarked questions. The essential information the learner needs is that the intonation contour stays high at the end of particle questions (Tā qù ma? 他去吗?), unmarked questions (Tā qù? 他去?), and unfinished units , while it drops at the end of statements (Tā qù le. 他去了。) and other types of question (Tā qù bù qù? 他去不去? Shéi qù? 谁去?).

7 Conclusion

The pronunciation of Chinese is rather difficult to acquire. This is largely due to the tonal character of Chinese. Yet pronunciation does not seem to receive due attention in SC pedagogy. In addressing the various aspects of pronunciation, both textbooks and teaching materials tend to be rather elementary and conservative, not to mention the insufficient space they allocate to this issue. Few language teachers have a deep level of insight into (SC) phonetics and phonology . The renowned Chinese linguist, phonetician and pedagogue, Lin Tao (passed away in 2006) calls for the breaking up of the old framework of SC pronunciation teaching and identifies the need to seek more effective approaches, utilizing the results of phonetic research. Lin complains in his Foreword to Hanyu yuyin jiaocheng (Cao 2002: 5), appraised by him as a herald of the modern approach:

The proportion of teaching pronunciation within the whole teaching curriculum is ever decreasing. An inevitable result is that foreign students commonly speak Chinese with a strong accent (洋腔洋调). However, because we neither attach enough importance to teaching pronunciation nor have proper methods, this phenomenon does not decrease, becoming all the more striking instead… Judging from both my own pedagogical experience as a whole, and from discussions focused on particular topics , one can rarely see an endeavor to introduce the expert knowledge of Chinese phonetics and scholarly literature into teaching Chinese as a second language in a comprehensive, systematical way that would take into account the overall needs of L2 teaching.

The major task for the future seems to be to bring instruction on SC pronunciation in line with the findings of SLA research, to develop a modern methodology drawing on the pool of research in phonetics and phonology , and to include it in teaching materials and the training of pedagogues. The scope should go beyond the basic fundamentals and cover the whole range of topics up to sentence intonation and pragmatics. This, of course, requires pronunciation to be granted a decent space within the whole teaching curriculum. Although doing so might somewhat slow down progress in grammar, and the learning of new characters, new words, phraseology, etc., the time invested would undoubtedly pay off in the long term. The magnitude of these tasks is significant. The present chapter has attempted to provide some inspiration with respect to these issues.

Notes

- 1.

Pinyin items are in italics.

- 2.

The abbreviation CASLAR stands for Chinese As a Second Language Research. The 4th CASLAR biennial conference was held in Shanghai in August 2016.

- 3.

NACCL is the North American Conference on Chinese Linguistics. NACCL-27 was held in Los Angeles (UCLA) in April 2015.

- 4.

The abbreviation BLCU stands for Beijing Language and Culture University (formerly the Beijing Language Institute).

- 5.

The author of the notion of a ‘phonological sieve’ is N. S. Trubetzkoy (Grundzüge der Phonologie, 1939).

- 6.

Note that the IPA transcriptions of particular SC sounds may have their problems, as well as there being a lack of consensus among authors etc. For instance, the consonant written as r in Pinyin is alternatively transcribed as a fricative [ʐ], as an approximant [ɻ] or as an approximant [ɹ]. The choice between a fricative and an approximant is conditioned by the placement of this consonant in a SC phonological system, which differs from author to author.

- 7.

An ingenious phonological analysis of the system of SC finals within a traditional framework is offered by Dragunov and Dragunova (1955); their analysis has a pedagogical potential.

- 8.

Note that some analyses only accept falling diphthongs, e.g. Duanmu (2002: 42).

References

Cao, W. (2002). Hanyu yuyin jiaocheng [A course in Chinese phonetics]. Beijing: Beijing Language and Culture University Press.

Cao, W. (2010). Xiandai hanyu yuyin dawen [Questions and answers about Chinese phonetics]. Beijing: Beijing Language and Culture University Press.

Chao, Y. R. (1925). A phonograph course in the Chinese national language. Shanghai: Commercial Press.

Chao, Y. R. (1968). A grammar of spoken Chinese. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Ch’en, T.-T., Link, P., Tai, Y.-J., & Tang, H.-T. (1989). Chinese primer (Vol. I.-IV). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Cheng, C. (1973). A synchronic phonology of Mandarin Chinese. The Hague: Mouton.

Chin, T. (2006). Sound systems of Mandarin Chinese and English: A comparison. München: LINCOM Studies in Asian Linguistics.

Dow, F. D. (1972). An outline of Mandarin phonetics. Canberra: Australian National University Press.

Dragunov, A. A., & Dragunova, J. N. (1955). Struktura sloga v kitajskom nacional’nom jazyke [Syllable structure in the Chinese national language]. Sovetskoje vostokovedenije, 1, 57–74. Moskva: Izdatel’stvo Akademii nauk SSSR [Chinese translation: Long Guofu and Long Guowa, Zhongguo Yuwen, 1958, 11, 513–521.]

Duanmu, S. (2001). Stress in Chinese. In D. Xu (Ed.), Chinese phonology in generative grammar (pp. 117–138). London: Academic Press.

Duanmu, S. (2002). The phonology of Standard Chinese. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hockett, C. F. (1951). Progressive exercises in Chinese pronunciation [Far Eastern Publications, Mirror Series 2]. New Haven: Yale University.

Huang, R. (1969). Mandarin pronunciation. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Jiang, H. (2010). Hanyu yudiao wenti de shiyan yanjiu [Experimental research on the problems of Chinese intonation]. Beijing: Capital Normal University Press.

Jones, R. H. (1997). Beyond “listen and repeat”: Pronunciation teaching materials and theories of SLA acquisition. System: An International Journal of Educational Technology and Applied Linguistics, 25(1), 103–112.

Kane, D. (2006). The Chinese language: Its history and current use. Singapore: Tuttle Publishing.

Kratochvil, P. (1968). The Chinese language today. London: Hutchinson University Library.

Ladefoged, P., & Maddieson, I. (1996). The sounds of the world’s languages. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Ladefoged, P., & Wu, Z. (1984). Places of articulation: An investigation of Pekingese fricatives and affricates. Journal of Phonetics, 12, 267–278.

Lee, W., & Zee, E. (2003). Illustrations of the IPA: Standard Chinese (Beijing). In Handbook of the International Phonetic Association (pp. 109–112). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lee, W., & Zee, E. (2014). Chinese phonetics. In J. Huang, Y.-H. A. Li, & A. Simpson (Eds.), The handbook of Chinese linguistics (pp. 369–399). Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

Li, W. (1999). A diachronically motivated segmental phonology of Mandarin Chinese. New York: Peter Lang.

Liang, L. (2003). Shengdiao yu zhongyin – hanyu qingsheng de zai renshi [Tone and stress – Revisiting the Chinese neutral tone]. Nankai University, Department of Chinese Language and Literature. Journal of the Graduates, 5, 59–64.

Lin, T. (2001a). Tantao Beijinghua qingyin xingzhi de chubu shiyan [Discussing preliminary experiments on the nature of non-stress in Pekingese]. In T. Lin (Ed.), Lin Tao yuyanxue lunwenji [Linguistic essays by Lin Tao] (pp. 120–141). Beijing: Commercial Press.

Lin, T. (2001b). Hanyu yunlü tezheng he yuyin jiaoxue [Prosodic features of Chinese and the teaching of phonetics]. In T. Lin (Ed.), Lin Tao yuyanxue lunwenji [Linguistic essays by Lin Tao] (pp. 208–218). Beijing: Commercial Press.

Lin, Y.-H. (2007). The sounds of Chinese. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lin, Y.-H. (2014). Segmental phonology. In J. Huang, Y.-H. A. Li, & A. Simpson (Eds.), The handbook of Chinese linguistics (pp. 400–420). Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

Lin, T., & Wang, L. (2003). Yuyinxue jiaocheng [A course in phonetics]. Beijing: Beijing University Press.

Lin, H., & Wang, Q. (2007). Mandarin rhythm: An acoustic study. Journal of Chinese Linguistics and Computing, 17(3), 127–140.

Liu, X. (Ed.) (2010). Xin shiyong hanyu keben [New practical Chinese reader] (2nd ed.). Beijing: Beijing Language and Culture University Press.

Liu, X., Deng, E., & Liu, S. (1981). Shiyong hanyu keben [Practical Chinese reader] (1st ed.). Beijing: Commercial Press.

Liu, Y., Yao, T., Bi, N., Ge, L., & Shi, Y. (2009). Integrated Chinese (3rd ed.). Boston: Cheng & Tsui Company.

Norman, J. (1988). Chinese. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ohnesorg, K., & Švarný, O. (1955). Etudes expérimentales des articulations Chinoises. Praha: Rozpravy Československé akademie věd, 65(5).

Peng, S., Chan, M. K. M., Tseng, C., Huang, T., Lee, O. J., & Beckman, M. E. (2005). Towards a pan-Mandarin system for prosodic transcription. In S.-A. Jun (Ed.), Prosodic typology: The phonology of intonation and phrasing (pp. 230–270). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Roach, P. (1996). English phonetics and phonology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shen, X. S. (1989). The prosody of Mandarin Chinese. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Shih, C. (1988). Tone and intonation in Mandarin. Proceedings from the Working papers of the Cornell Phonetics Laboratory, 3, 83–109.

Spada, N., & Lightbown, P. (2008). Form-focused instruction: Isolated or integrated? TESOL Quarterly, 42(2), 181–207.

Spencer, A., & Luís, A. R. (2012). Clitics: An introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sun, C. (2006). Chinese: A linguistic introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tao, H. (2015). Profiling the Mandarin spoken vocabulary based on corpora. In C. Sun & S. Y. W. Wang (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of Chinese linguistics (pp. 336–347). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Třísková, H. (Ed.) (2001). Tone, stress and rhythm in spoken Chinese. Journal of Chinese Linguistics (Monograph series 17). Berkeley: University of California.

Třísková, H. (2011). The structure of the Mandarin syllable: Why, when and how to teach it. Archiv Orientální, 79(1), 99–134.

Třísková, H. (2012). Segmentální struktura čínské slabiky [Segmental structure of the Mandarin syllable]. Praha: The Publishing House of Charles University Karolinum.

Třísková, H. (2016). De-stressed words in Mandarin: Drawing parallel with English. In H. Tao (Ed.), Integrating Chinese linguistics research and language teaching and learning (pp. 121–144). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Třísková, H. (in press). De-stress in Mandarin: Clitics, cliticoids and phonetic chunks. In I. Kecskes & C. Sun (Eds.), Key issues in Chinese as a second language research. London: Routledge.

Tseng, C. (1990). An acoustic phonetic study on tones in Mandarin Chinese. Taipei: Academia Sinica.

Tutatchnikova, O. P. (1995). Acquisition of Mandarin Chinese pronunciation by foreign learners: The role of memory in learning and teaching (Unpublished master’s thesis). The Ohio State University. https://etd.ohiolink.edu/!etd.send_file?accession=osu1239365453. Accessed 28 Oct 2015.

Wang, Y., & Wang, L. (Eds.) (2013). Yuyinxue jiaocheng [A course in phonetics]. Beijing: Beijing University Press.

Wang, L. et al. (2002). Xiandai hanyu [Modern Chinese]. Beijing: Commercial Press.

Wu, Z. (Ed.) (1992). Xiandai hanyu yuyin gaiyao [An outline of Modern Chinese phonetics.] Beijing: Sinolingua.

Xu, S. (1999). Putonghua yuyin changshi [Basic facts about Standard Chinese phonetics]. Beijing: Language and Culture Press.

Xu, Y. (1997). Contextual tonal variations in Mandarin. Journal of Phonetics, 25(1), 61–83.

Xu, Y. (2015). Intonation in Chinese. In C. Sun & S.-Y. Wang (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of Chinese linguistics (pp. 490–502). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Yang, J. (Ed.) (1999). Hanyu jiaocheng [A course in Chinese]. Beijing: Beijing Language and Culture University Press.

Yip, M. (2002). Tone. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yu, Z. (2004). Lun hanyu “si sheng er zhi” de xin moshi [About a new model “four tones – two values” in Chinese]. In Proceedings from the fourth international conference on Chinese Teaching (pp. 351–353). Kunming: Yunnan Normal University.

Zeng, Y. (2008). Duiwai hanyu yuyin [Teaching Chinese phonetics to foreigners]. Changsha: Hu’nan Normal University Press.

Zhou, D., & Wu, Z. (1963). Putonghua fayin tupu [Articulatory diagrams of Standard Chinese]. Beijing: Commercial Press.

Zhu, C. (Ed.) (1997). Waiguo xuesheng hanyu yuyin xuexi duice [Strategies to support the learning of Chinese phonetics: A handbook for foreign students]. Beijing: Language and Culture Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Třísková, H. (2017). Acquiring and Teaching Chinese Pronunciation. In: Kecskes, I. (eds) Explorations into Chinese as a Second Language. Educational Linguistics, vol 31. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54027-6_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54027-6_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-54026-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-54027-6

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)