Abstract

Introduction. To promote better sexual health, it is essential to gather accurate data regarding the sexual behaviors of the population. Numerous surveys about sexual habits have been published throughout history, some of them more rigorous and scientifically valid than others.

A brief history of sex surveys. The first known sex surveys in the United States were published by Kinsey (1948 and 1953), who surveyed sexual behaviors in humans. His findings, particularly those pertaining to homosexuality, were highly influential, but his sampling method was criticized. The National Health and Social Life Survey (NHSLS), published in 1993, and the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior (NSSHB), published in 2010, are the most recent population-wide sex surveys.

Prevalence of sexual behaviors. According to the NSSHB, the majority of men and women masturbate. The most common sexual act is vaginal sexual intercourse. The rates of various sexual behaviors reported by the NSSHB are overall similar to those reported by the NHSLS.

Homosexuality. Psychiatry’s view on homosexuality has evolved dramatically since the middle of the century, as has society’s in general. The widely reported figure of “10% of Americans are homosexuals” has been shown by most surveys to be overstated.

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and AIDS. The NHSLS and NSSHB have shown that, since the appearance of HIV, the behavior of at-risk populations has evolved toward safer sex practices. Older individuals, however, are nowadays more sexually active and practice safe sex at a lower rate than younger individuals.

Prevalence of sexual disorders. The scarcity of large-scale epidemiological data has led researchers to rely on integrating the data from smaller studies.

Conclusion. Although the sexual act remains one of the most private events, it continues to have major public health repercussions. The gathering of accurate data regarding sexual behaviors remains more important than ever.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Few topics elicit as much passionate discussion, debate, and controversy as that of sex. As a result, a frank public health-oriented conversation free from taboo and prejudice remains difficult, even in the early twenty-first century, as evidenced by the recent controversy regarding the administration of the quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in teenagers [1]. The ensuing moral panic echoed that which followed the publication of the Kinsey Reports in the 1950s and that surrounding the issue of public funding of the National Health and Social Life Survey (NHSLS) in the late 1980s. The polemic recurs with every public discussion about sexual health, leading former Surgeon General of the United States M. Jocelyn Elders, M.D., to write, “We have a sexually dysfunctional society because of our limited views of sexuality and our lack of knowledge and understanding concerning the complexities and joys of humanity. We must revolutionize our conversation from sex only as prevention of pregnancy and disease to a discussion of pleasure [2]. This discussion cannot occur in the absence of accurate and dispassionate data.

Furthermore, in 2002, the World Health Organization (WHO) updated its definition of sexual health which it now defines as “a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being related to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity. Sexual health requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual responses, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and violence” [3]. In the era of HIV/AIDS, the very private sexual act may have major public health repercussions.

In order to promote better sexual health, as defined by the WHO, it is essential to gather accurate data regarding the sexual behaviors and sexual health of the population. From Kinsey to the present day, numerous surveys about sexual habits have been published (Table 3-1); some of them were rigorous and scientifically valid, others less so. All sought to satisfy the public’s curiosity for this most unique topic. The following chapter aims at reviewing the major surveys of sexual behaviors and sexual disorders and to present their main findings, focusing mainly and whenever possible on surveys pertaining to the US population.

A Brief History of Sex Surveys

The first known sex surveys in the United States were the Kinsey Reports, published in 1948 and 1953. Alfred Kinsey was an evolutionary biologist and a professor of zoology from Indiana University who had never studied human behavior. The main focus of his early research was in fact the mating practices of gall wasps [4]. In 1938, he was asked to teach the sexuality section of a course on marriage. As he was looking up literature in preparation for his lectures, he realized that scarcely anything had been published on the topic. He then decided to conduct his own study, using taxonomic methods transposed from entomology with which he was familiar. He started by handing out questionnaires to his class students, soon switching to face-to-face interviews. Along with his three colleagues, he ended up interviewing close to 18,000 subjects. He used samples of convenience starting with his own students, later expanding to other college students, prison inmates, mental hospital patients, a group of homosexuals, and hitchhikers. His findings were published in two books, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male in 1948 [5], followed 5 years later by Sexual Behavior in the Human Female [6]. These two works were later collectively dubbed the Kinsey Reports. They challenged preconceived notions about sex, a topic which was previously deemed taboo. Notably, Kinsey’s data was presented free of any social, cultural, or political taboos [7]. The controversial nature of the topic naturally invited a backlash. Many critics, including religious and political figures, feared that Kinsey’s candid discussion of sexual practices would disrupt the moral order of the nation. Nevertheless, the Reports soon reached the top of bestseller lists, turning their author into a celebrity.

Some of Kinsey’s most famous and controversial findings concerned homosexuality . He reported that 37% of men had at least one sexual encounter with another man at some point in their life and that 46% of men “reacted” sexually to persons of both sexes. Ten percent of men had had sex exclusively with other men for at least 3 years [5]. This figure may be the basis of the oft-repeated assertion that “10% of Americans are homosexual.” Kinsey himself however avoided the categories “homosexual” and “heterosexual,” instead using a seven-point scale—later dubbed “Kinsey scale ”—to describe a person’s sexual orientation, ranging from 0, or “exclusively heterosexual,” to 6 or “exclusively homosexual” [5]. Regarding women, Kinsey reported that 7% of single females aged 20–35, as well as 4% of previously married women from that same age group, had equal heterosexual and homosexual experiences or responses (a rating of 3 on the Kinsley scale). One to three percent of single females of that age group were reported to be exclusively homosexual [6].

Kinsey estimated that the average frequency of marital sex among women in their late teens was almost three times a week, and it decreased to a little over two times a week at age 30 and once a week by age 50 [6]. On the topic of masturbation , he reported that 62% of female responders partook of it, 45% of which indicated that they could achieve orgasm in less than 3 min [6]. The rate of masturbation in males was markedly higher, at 92% [5].

Kinsey reported that around 50% of all married males had had an extramarital affair at some point during their married life, as did 26% of females under 40. He estimated that between 1 in 6 males and 1 in 10 females aged 26–50 had engaged in extramarital sex. Eighty-six percent of men reported that they had engaged in premarital sex, as did half of the women who married after World War I.

Additionally, Kinsey reported that 50% of males and 55% of females endorsed having responded erotically to being bitten. Furthermore, 22% of males and 12% of females reported an erotic response to a sadomasochistic story [5, 6].

Although his reports are still regarded as foundational works in sex surveys and the study of sex in general, Kinsey’s methodology was heavily criticized, especially his use of convenience samples. His rationale for not using a random sample was that he could not persuade a random sample of Americans to answer deeply personal questions about sexual behavior. The result is a sample which, despite being considerable in size, may not be representative of the general population, as is generally the case with convenience samples [8]. Some groups were overrepresented in the sample. For instance, 25% of respondents were or had been prison inmates, and 5% were male prostitutes. One vocal critic even asserted that “a random selection of three people would have been better than a group of 300 chosen by Mr. Kinsey” [9]. Additionally, many of Kinsey’s respondents volunteered to be in the study. Subsequent investigations showed that individuals who volunteer for surveys are often not representative of the entire population [10]. Nevertheless, Kinsey’s work has been described as “monumental ” [11] and has been named as one of the factors that changed the general public’s perception and eventually led to the sexual revolution of the 1960s. It also led the way for the next generation of sex researchers. Indiana University’s Institute for Sex Research (later renamed Kinsey Institute) has strived to expand and update the trove of information left behind by its founder. Subsequent studies were conducted, most notably in 1970 and in 2009. They are presented below. Researchers in other countries also emulated Kinsey. A notable example is the survey conducted in the United Kingdom in 1949 by the social research organization Mass-Observation. It was dubbed “Little Kinsey” although, unlike its model, it was conducted using random sampling [12].

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Washington University gynecologist William Masters and his research associate and eventual wife Virginia Johnson studied sexual behavior using a medical model. They described the anatomy and physiology of human sexual response by observing 382 women and 312 men engaging in “10,000 complete cycles of sexual response.” Their findings were published in Human Sexual Response (1966) [13] and Human Sexual Inadequacy (1970) [14].

The next major study was funded by the NIMH and was conducted by Indiana University’s Institute for Sex Research, under the direction of Albert D. Klassen, subsequently joined by Eugene E. Levitt and carried out by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) at the University of Chicago. It was originally conceived as a survey of the public’s perception of homosexuality but was later expanded to cover a wide variety of sexual behaviors and attitudes. A fairly large sample of Americans (3018 respondents) were surveyed from 1970 to 1972. The data gathering process was slower and more expensive than anticipated, and the data analysis and writing processes were mired in controversy and personal disputes. As a result, the manuscript, which was finished as early as 1979, was not published. It was not until 1988 that the text re-emerged [15]. What Science had dubbed “The Long, Lost Survey on Sex” [16] was eventually published in 1989 as Sex and Morality in the U.S. [15], with additional data published in Science [17]. The main interest of the study lies in the fact that it dealt primarily with perceptions of sexual practices rather than the prevalence of the practices themselves. The researchers reported that 48% of respondents disapproved of masturbation, and a vast majority disapproved of extramarital coitus and homosexual relations without affection (87 and 88%, respectively). Even homosexual relations with affection had a disapproval rating of 79%. Similarly, a majority (65–82%) disapproved of premarital sex in teenagers, whether boys or girls, with or without romantic love. Adult age and the presence of love were predictors of a lower disapproval rate. Still, 29% of responder approved of outlawing premarital sex, 59% favored laws against homosexuality, and 14% believed a person convicted of homosexuality should be sentenced to at least a year in prison [15].

In subsequent years, there were other smaller studies, targeting certain specific population groups, such as young women [18,19,20] or college students [21]. These studies tended to focus more on social issues, such as contraception and teenage pregnancy, rather than actual sexual practices [22].

In the absence of rigorous scientific studies of sexual practices , a number popular nonscientific or pseudoscientific reports attempted to assuage the public’s curiosity about the topic. More often than not, these studies used convenience samples. For instance, a number of these studies were funded by and published in magazines, and they drew their samples from the readership of said magazines. These include Psychology Today [23], Redbook [24], and Playboy [25].

The samples used in the studies may be large—20,000 in the case of Psychology Today , more than five times more for the Redbook study. However, these samples are drawn from the readers of the publications, and it has been argued that these are an already preselected population not necessarily representative of the general population, especially in terms of liberalism and education [15]. An additional issue is that of response rate. In the case if the Redbook survey, a survey was sent out to 4,700,000 Redbook readers , and only 2% of them responded. Such a response rate casts doubts as to the representative abilities of the findings, a shortcoming that will plague many other such surveys, such as that conducted by American-born German sex educator Shere Hite. Hite sent out surveys to women whose names she obtained from women’s organizations and subscriber lists of women’s magazines. In total, she distributed 100,000 questionnaires and received 3000 of them back, a 3% response rate [26].

The Janus Report (1993), by Samuel S. Janus and Cynthia L. Janus, was distributed to 4550 subjects with 2795 returned and were “satisfactorily completed” [27]. These included volunteers who came to the offices of sex therapists. It presents itself as an updated snapshot of American sexual practices in the context of the AIDS epidemic that had started a decade earlier. The report claimed to be going against preconceived notions about the sexual habits of senior citizens. It reported that over 70% of Americans ages 65 and older have sex once a week. The rate reported is almost as high in men over 65 (69%) as in men aged 18–26 (72%). It even went on to claim that a similar proportion of men over 65 have sex every day (14%) as men aged 18–26 (15%). The Januses’ conclusions contradicted previous—and subsequent—studies that found a gradual decline in sexual activity beginning in the fifties. The Janus Report was heavily criticized for its skewed sampling, which resulted in overestimating the rates of sexual behaviors. For instance, Arthur Greeley [28] systematically compared the results obtained by the Januses to results drawn from the General Social Survey (GSS) , which was based on a national household-based probability sample conducted by the National Opinion Research Center over two decades. He found that the Janus Report estimates were often 2–10 times higher than those of the GSS. For instance, as mentioned above, the Janus Report estimates that 69% of men aged 65 and above have sex at least once a week, as do 72% of men aged 18–26. By comparison, GSS rates for these age groups are 17 and 57%, respectively. The fact that the Januses’ findings were never replicated elsewhere seems to give credence to their detractors.

In 2004, ABC News Primetime Live published its own American Sex Survey . The researchers interviewed 630 American adults by telephone, out of a random national sample of 1501. The survey lavishly describes “eye-popping sexual activities, fantasies and attitudes in this country.” Among the results is 42% of Americans call themselves “sexually adventurous,” 30% of single men aged 30 and older have “paid for sex,” and that half of women acknowledge having “faked an orgasm” [29].

The scarcity of serious up-to-date studies and the urgent necessity of accurate information about sexual behaviors as a matter of public health, especially in the era the HIV epidemic, were the drivers behind the National Health and Social Life Survey (NHSLS) in 1990 [30]. The NHSLS, sometimes dubbed the Chicago Study or Chicago Survey, sought to remedy what its authors saw as methodological flaws in all previous sex surveys, from Kinsey on. The purpose of the NHSLS, according to one of its authors, was to “collect and analyze data on the social organization of sexual behavior, particularly the social structuring of sexual action, and the ways in which that structuring influences behaviors that increase the incidence and prevalence of a variety of health-related problems” [22]. The inception of the NHSLS was not without controversy. The study of people’s private sexual behaviors has long been contentious, as evidenced by the vivid reactions to the Kinsey Reports. The government was reluctant to fund a project which would “provide a mandate of excessive sexual expression” [31], and although the study was originally requested by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), its funding was soon terminated. The researchers were thus forced to turn to private donors to fund the study, including the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the American Foundation for AIDS Research. The NHSLS was headed by Edward O. Laumann, Research Associate at NORC; John H. Gagnon, Professor of Sociology and Psychology at the State University of New York at Stony Brook; Robert T. Michael, NORC founding director; and James Coleman, NORC Research Associate [8].

The NHSLS used a novel approach in sampling. It involved a multistage area probability sample designed to give each household an equal probability of inclusion. The sampling returned 4369 eligible respondents. These subjects were administered a face-to-face 90-min survey, 3432 of which responded and were thus included in the study, resulting in a response rate of 78.6%. The subjects were aged 18–59, including 75% Whites, 12% African Americans, and 8% Hispanic Americans.

NHSLS researchers reported on a wide array of topics, such as sexual fantasies, masturbation, orgasm, and emotional satisfaction. Some of the findings from this survey are highlighted later in this chapter. The results of the study were published in Sex in America: A Definitive Survey [8] and The Social Organization of Sexuality [22]. Among the NHSLS findings was the fact that Americans tend to engage in sexual intercourse with peers who are similar to themselves in age, education, and ethnicity. It also revealed that, at the time, most sexually transmitted infections were contracted by young adults. 16.9% of respondents reported that they had at some point been diagnosed with at least one sexually transmitted infection. The survey also reported a correlation between the number of both lifetime and simultaneous sexual parwtners and the likelihood of contracting a sexually transmitted infection. Those with more than 10 lifetime sexual partners were 20 times more likely to have contracted such an infection as those with only one. Interestingly, the NHSLS found that the populations at highest risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections were starting to change their sexual practices accordingly, for instance, with increased condom use.

Overall, according to Cooks and Baur, the NHSLS “stands alone as the most representative U.S. sex survey and as one that reliably reflects the practices of the general U.S. adult population in the 1990s” [31]. Nevertheless, the study had some important shortcomings. As the NHSLS was conceived in the wake of the AIDS epidemic, it was in part designed to understand sexual behaviors associated with the transmission of the disease, so the researchers focused mainly on sexual practices that may lead to infection, omitting many significant non-genital sexual acts such as hugging, kissing, and body stroking, as well as the events surrounding the act such as courtship. Another major limitation has been the exclusion of adolescents and older adults, as the NHSLS researchers have chosen to focus solely on adults aged 18–59. It was in order to remedy to these limitations that some more cohort-specific surveys have appeared in recent years. The Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) , conducted by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has strived since 1991 to gain data in the adolescent population, studying health risk and health protective factors in 9th to 12th graders, including sexual behavior [32,33,34]. The National Social Life, Health and Aging Project (NSHAP) , on the other hand, researches the elderly population [35].

An all-encompassing survey to cover all age groups remained absent until two decades later, with the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior (NSSHB) conducted by the Kinsey Institute and Indiana University. The NSSHB not only provided an expanded age group but also allowed insight into changing trends and developments in sexuality over the past 20 years [36]. The NSSHB studied nearly 6000 subjects aged 14–94 and provided the scientific community with the first batch of thorough data on human sexuality and sexual behaviors in the past two decades. The NSSHB also took into consideration new developments in society which could influence sexuality. Such changes include the use of medications to treat erectile dysfunction (sildenafil, marketed as Viagra®, was released in 1998) which had extended the sexual lives of many and increased sexual behaviors in older ages. Also, in contrast to the 1970 Kinsey survey, same-sex relationships were now viewed differently, as same-sex marriage had become legal in some states and there had been increased recognition of same-sex partnerships and lifestyles. Another major development was the possible influence of the Internet on sexual perceptions and practices. The ability of the NSSHB to consider this influence on sexuality provides data, which researchers hoped would be more representative of the national population [37].

The NSSHB set out with the expressed aim to be the most nationally representative sexual survey conducted to date. It enrolled a total of 5865 participants (2936 males and 2929 females) through a population-based cross-sectional study conducted in the spring of 2009, randomized using random digit dialing and address-based sampling. This allowed the sampling frame to cover approximately 98% of all US households. Ages included ranged from 14 to 94, with adolescents requiring consent from their parent or guardian. Sample adjustments made included gender, age, race (Black, Hispanic, White, or other), geographic region (Midwest, North, South, West), sexual orientation (heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, asexual, or other), household income, level of education, and relationship or marital status. Participants were asked to report whether or not they had engaged in certain solo or partnered sexual behaviors and, if so, how recently (never, within the past month, within the past year, or more than a year ago). These reports were obtained via the Internet, as opposed to face-to-face interviews in past surveys. Findings were presented as 95% confidence intervals sorted by age cohorts. Sexual behaviors included masturbation (solo and partnered), vaginal intercourse, anal intercourse, and same-sex behaviors. Condom use during vaginal intercourse was also assessed [37].

The NSSHB claimed to be a more modern sexual survey in comparison to previous studies, arguing that its design and items of investigation allow for a better insight into the sexual health of the US population. Investigation of earlier ages (younger than 18) provided insights into young teens, who have been considered a higher-risk demographic. Investigation of older ages (over 60) has allowed a better understanding of sexuality in an age group which has seen an extended sexual life due to the pharmacological advancements, an expanded range of sexual enhancement products (vibrators, lubricants), and consumer marketing messages that shape expectations for sex and relationships at an advanced age. Another particularity of the NSSHB lies in its methodology for data acquisition; the researchers claimed that, since answers were sent via the Internet, they were likely to be more honest than face-to-face answers such as those of the NHSLS, the latter being thought as more anxiety provoking and not allowing for the same degree of honesty. Nevertheless, the study did have its own major limitations. In particular, in a recurrent problem common to many sex surveys, the sample may have been subject to self-selection, as those who chose to participate may represent different sexual personalities than those who chose not to participate. Also, subjects sampled were only those accessible in the community and not those in group homes, hospitals, or long-term care facilities. Such factors are important and should be taken into consideration when designing future sexual surveys.

Although this chapter focuses primarily on surveys of sexual behaviors conducted in the United States, there were many more carried out in various parts of the world. Listing them all would be far outside the purview of this volume, but one notable study is the Sexual Well Being Global Survey, or SWGS , conducted by Kevan Wylie, M.D., of the United Kingdom in 2006 and published in 2009. The researchers surveyed 26,032 participants across 26 countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, China, Brazil, and Nigeria. The study was conducted online except for Nigeria where the respondents were interviewed face-to-face. The listed objective of the study was to “identify the variety of sexual behaviors undertaken by adults across the world.” The researchers found that three out of five respondents globally said that sex was important to them, with comparable findings in men and women. Sixty-nine percent of those surveyed enjoyed sex. Forty-four percent of participants were “very or extremely satisfied” with their sexual life [38].

Prevalence of Sexual Behaviors

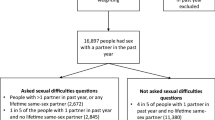

The following data regarding the prevalence of sexual behaviors are mainly derived from the most recent nationally representative sexual surveys, the NSSHB [8, 22] and NHSLS [36,37,38,39,40,41] (Figures 3-1 and 3-2).

Women’s rates of sexual acts by age (Based on data from Ref. [39]).

Men’s rates of sexual acts by age (Based on data from Ref. [42]).

Sexual Fantasies

The NHSLS survey found that 54% of men think about sex at least every day, 43% of them a few times a week or a month, and 4% less than once a month or never. In contrast, 19% of women think about sex at least every day, 67% of them a few times a week or a month, and 14% less than once a month or never. The survey also reported that 84% of married couples fantasized during intercourse. The most common fantasies, in decreasing order, are sex with the partner, sex with a stranger, sex with more than one person at a time, and engaging in sexual behaviors one would not usually engage in in reality [22].

Masturbation

According to the data gathered by the NSSHB , solo masturbation was reported by more than 20% of women in all age groups during the past month and by more than 40% within the past year, with the exception of those aged 70 years and more [37]. More than half of women aged 18–49 had masturbated in the past 90 days, including more than 60% of women aged 25–29. Being in a relationship and perceived health status are not significant factors in solo masturbation practices, except for women aged 60–69 who were less likely to masturbate if in a relationship. Forty-eight percent of women aged 18–39 reported masturbation “a few times each month or more” [39].

The NSSHB also found that the majority of men in all age groups reported masturbation in the past year with the exception of those aged 14–15 and 70 and more. Solo masturbation was more commonly reported than the majority of partnered sexual behaviors for men aged 14–24 and men aged 50 years or older [37]. It also reported that about half of men aged 18–69 masturbated in the past 90 days. Men aged 25–39 were the ones who engaged most frequently in solo masturbation, including 95.5% of men who describe themselves as single and dating, and more than 80% of all unmarried men from that age group. Married men over 70, in contrast, had the lowest rate (27%). Partnered men were less likely to report masturbation than non-partnered men. Health status was not a factor, except for men over 70 for whom poor to fair health was associated with lower rates of masturbation (18%) than those with good to excellent health (40%). More than 30% of men aged 18–49 reported masturbation alone on average more than twice a week during the past year [42].

NSSHB reported that women aged 25–29 were most likely to have engaged in partnered masturbation in the past 90 days (35%), as were men aged 30–39 (33%). Women who were in a relationship were more likely to engage in the practice than women who were not and perceived health status was not a significant factor. Men in a relationship were also more likely to engage in the practice. In women aged 25–39, the practice was most frequent in those who identified as single and dating (more than 60% engaged in it in the past 90 days). The highest rate in men when factoring all variables was among 25–29-year-olds in a relationship but not living together (44%) [37].

Two decades earlier, the NHSLS found that 63% of men and 42% of women masturbated at least once a year; 29% of men and 9% of women masturbated once a week. Eighty-one percent of men and 61% of women achieved orgasm during masturbation; 54% of men and 47% of women felt guilty afterwards. Individuals with a master’s or advanced degree tended to masturbate at a higher rate (81% of men and 59% of women) than those without a high school degree (68% of men and 48% of women). Overall, the NHSLS finds that the higher the education level, the more likely the individual is to report that he or she masturbates. The NHSLS also reported that Whites masturbated more (66% of men, 44% of women) than Blacks (40% of men, 32% of women). In married individuals, the proportions of those who masturbated at least once a year is 57% in men and 37% in women, compared to 70 and 47%, respectively, in men and women who are divorced, separated or widowed, and not in a relationship. When asked for the reasons for masturbation , 40% of men and 42% of women said they sought physical pleasure; 26 and 32%, respectively, said it was to relax; 73 and 63% said they did it to relieve sexual tension; 32 and 32% cited the absence of a partner; and finally 11 and 5% said they did it out of boredom [22].

Partnered Sexual Intercourse

The NHSLS in 1992 looked at the frequency of all sexual contacts, whether vaginal, oral, anal, or others. According to the data reported, about a third of respondents (37% of men and 33% of women) engaged in sexual intercourse with a partner at least twice a week, another third (35% of men and 37% of women) engaged in intercourse a few times a month, and the rest engaged in intercourse a few times a year or not at all. Ten percent of men and 14% of women had not had sex at all in the past year. The youngest and the oldest respondents in the NHSLS survey were the least active sexually. People in their twenties were the most active, with 48% of men and 33% of women in that cohort engaging in intercourse twice a week or more. For both men and women, married and cohabiting couples engaged in sexual intercourse more frequently than non-cohabitating individuals. Contrary to perceived stereotypes, the survey did not find any significant variation in frequency of sexual activity across different racial groups, religions, or levels of education. Data from surveys showed that 40% of married people and half of people who were living together engaged in intercourse twice a week or more. Fewer than 25% of single or dating men and women engaged in intercourse twice a week. Twenty-five percent of single people not living together reported to engage in intercourse “just a few times,” compared to 10% of married individuals. The length of the last sexual event of 11% of men and 15% of women was shorter than 15 min, and longer than an hour for 20% of men and 15% of women. Younger respondents appeared to have longer sexual encounters than older ones, with 31% of men and 23% of women aged 24 and less reporting that their last encounter lasted an hour or more, compared to 4% of men and 3% of women aged 55–59 [22].

Oral Sex

The NSSHB found that more than half of women aged 18–39 reported giving or receiving oral sex in the past 90 days, including 57% of women aged 25–29. Across all age cohorts, women who were in a relationship were more likely to report giving or receiving oral sex than those who were not. The highest rates were in women aged 25–29 who were living with a partner but not married, as 80% reported having received oral sex and 88% having given it in the past 90 days. Women in their thirties were most likely to receive (64%) and give (68%) oral sex among women who were single and dating. For most age cohorts, perceived health status was significantly associated with increased likelihood of oral sex in the past 90 days. Women aged 18–24 were the most likely to have reported oral sex with another woman in the past 90 days, with 3% reporting having received it and 4% having given it [39].

As for men, the NSSHB found that 64% of those aged 25–39 received oral sex from a female partner in past 90 days, and about 60% of them gave oral sex to a female partner. The men who were most likely to receive oral sex in this age cohort were in a non-cohabitating relationship (81%). In contrast, men over 70 had lower rates of receiving oral sex (15% in past 90 days). Being in a relationship was predictive of having received and having performed oral sex in the past 90 days for all men through age 69. Seven percent of men in their fifties reported having received oral sex from another man in past 90 days, and 7% reported having given it. This rate is higher than any other age cohort [42].

Interestingly, the data reported by the NSSHB is very similar to that of the NHSLS in the 1990s. At the time, the Chicago Study found that roughly three quarters of women reported cunnilingus having been performed on them by men and about the same proportion of men who reported fellatio performed on them by women. Around a quarter of respondents reported having performed oral sex on their partner during the last encounter, and about the same proportion reported receiving it. There was a sharp increase in the prevalence of these practices between those born between the 1930s and 1940s and those born afterwards, which coincided with coming of age sexually in the late 1960s and early 1970s, or the height of the so-called sexual revolution. Those respondents who reported no religious affiliation were more likely to have had experience with oral sex than Catholics or mainstream Protestants. Religiously conservative Protestants were the least likely to engage in the practice [22].

Vaginal Intercourse

The NSSHB reported that the majority of women aged 18–49 endorsed vaginal intercourse in the past 90 days (62–80%). In adult women, vaginal intercourse was the most frequently reported sexual behavior. After their thirties, more and more women reported having had no vaginal intercourse during the previous year: this was the case of about a quarter of women in their thirties, a third of women in their forties, half of women in their fifties, and finally four fifths of women over 70 [37]. Women aged 25–29 were most likely to report vaginal intercourse in the past 90 days (80%). Women in a relationship were more likely to report recent vaginal intercourse than women who were not; this difference increases with age, as 87% of women in their thirties who were in a relationship reported intercourse in the past 90 days, compared to 21% of non-partnered women. Among single women who were dating, the frequency was highest, perhaps surprisingly, in the 60–69 age cohort (81% in past 90 days). Higher perceived health status was associated with higher likelihood of vaginal intercourse in the past 90 days. The highest frequency of intercourse in women was in the 18–24 and 25–29 age groups. Women in a relationship reported more frequent intercourse, and frequency decreased with age [39].

As for men, those aged 25–30 and 30–39 were most likely to have had vaginal intercourse in the past 90 days (80 and 79%, respectively). Married men were more likely to have had intercourse than men in any other relationship status, and men in a relationship more than men who were not. The highest rates were in married men aged 18–24 and 25–29 (both 96%). Among single men who were dating, the frequency was highest among men in their thirties (76%). Health status was not a factor, except for men over 60 years as those with an excellent to good health status reported vaginal intercourse in the past 90 days at rates twice or more those with fair to poor health status [42].

Anal Intercourse

According to the NSSHB data, 10–14% of women aged 18–39 reported anal sexual intercourse in the past 90 days. The rate was highest in younger women with 14% of women aged 18–24 reporting anal intercourse in the past 90 days. Among women aged 18–24, a quarter of those who were cohabitating and a fifth of those who were married reported anal intercourse in the past 90 days. Women in a relationship were significantly more likely to report anal intercourse in the past 90 days. Among single women who were dating, those in their thirties were most likely to report such intercourse (14%). More than a quarter of married women aged 18–24 and women in a relationship aged 30–39 reported anal intercourse “once a month” to “a few times per year” [39]. As for men, insertive anal intercourse was more frequently reported in men aged 25–29 (16% in past 90 days), and men in a relationship were more likely to have practiced it if they were aged 18–24. Men aged 25–59 and in a relationship but not married were more likely to have had insertive anal intercourse than married or single men [42]. Anal intercourse among adolescents was rare (<5%) [43]. Within the past year, 13% of adult women and 3.6% of adult men reported having received anal sex. Sixteen percent of men reported insertive anal intercourse [37].

In comparison, the NHSLS had reported that 20% of women and 26% of men endorsed having had anal intercourse at some point in their lives. Of the respondents who have been active with a partner of the opposite sex in the previous year, around 9% reported anal intercourse in the previous year. There was a steady increase in rate between the cohorts born in the 1930s and 1950s, with a decrease in younger men and women, which the authors attributed to the HIV epidemic and resulting fear of transmission [22].

Homosexuality

Despite the fact that homosexuality has been documented since antiquity, its acceptance by modern Western societies as nonpathological is a fairly recent phenomenon. Alfred Kinsey asserted in Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (1948) that such behaviors were more common than previously thought. He also eschewed the categories “homosexual” and “heterosexual,” devising instead a seven-point scale [5], suggesting that homosexuality may be part of a spectrum of sexual behaviors instead of an isolated phenomenon. Nevertheless, change in attitudes was slow to come in the psychiatric field. Kinsey’s research was met mostly with indifference, if not hostility, by the specialty [44]. Homosexuality was still classified as a “sociopathic personality disturbance” in the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) in 1952 [45] and a “sexual deviation” in the second edition in 1968 [46]. A combination of a generational change in the field of psychiatry and relentless activism by members of the gay community led to an evolution in psychiatrists’ approach to homosexuality [47]. Judd Marmor, M.D., in particular, was key in bringing about the “depathologization” of homosexuals. As a psychoanalyst, he challenged the prevailing psychoanalytic views regarding homosexuality. His two books Sexual Inversion: The Multiple Roots of Homosexuality (1965) [48] and Homosexual Behavior : A Modern Reappraisal (1980) [49] were highly influential. Finally, in 1973, homosexuality was eliminated as a diagnostic category by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), and in 1980, the next edition of the DSM did not contain the diagnosis [50].

Societal views on homosexuality were also slow to evolve. A 1972 survey by the University of Indiana found that a vast majority of Americans still disapproved of homosexuality. Eighty-eight percent of respondents disapproved of homosexual relations without affection, and 79% disapproved of homosexual relations with affection. Fifty-nine percent were in favor of laws against homosexuality, and 14% asserted that a person convicted of homosexuality should be sentenced to at least a year in prison [15].

The demographic of homosexuality have long been a subject of contention. Kinsey’s reported that 37% of men had at least one sexual encounter with another man at some point in their life and that 46% of men “reacted” sexually to persons of both sexes [5]. His famous assertion that 10% of men had had sex exclusively with other men may be the basis of popular view that “10% of Americans are homosexual.” Kinsey also reported that about 13% of women have had at least one homosexual experience and that 1–3% of single females aged 20–35 were exclusively homosexual [6]. In 1993, the NHSLS reported that 1.4% of women and about 2.8% of men were identified as homosexuals. It also found that 6% of men reported sexual attraction to other men, and 2% of the men endorsed a sexual encounter with another man in the past year. Five percent of men had a sexual encounter with another man at least once since the age of 18. The survey also found that about 5.5% of the women reported that the thought of having sex with another woman was appealing or very appealing. Fewer than 2% of the women in the study had a sexual encounter with another woman in the past year, about 4% had a sexual encounter with another woman after the age of 18, and 4% of women had a sexual encounter with a woman at some point in their lifetime. The NHSLS found that people who identified as gay or lesbian tended to reside in urban areas and tended to be more highly educated. The survey found that 9% of men in the largest 12 cities in the United States identified themselves as gay, compared to 3–4% of men living in suburbs and 1% of men in rural areas. Three percent of college-educated men identified themselves as homosexual, compared to 1.5% of men with a high school degree. Women with college educations were eight times more likely to identify as gay than women with just high school educations (4 and 0.5%, respectively) [22]. More recently, a 2012 Gallup poll (Figure 3-3) reported that 3.4% of adults in the United States identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT). It also reported that 6.4% of adults aged 18–29 identified as LGBT, twice as many as those aged 30–49 (3.2%) and three times as many as those 65 or older (1.9%). The difference between genders was only significant in the younger demographics (aged 18–29), where women were reported to be twice as likely to identify as LGBT as men [51].

Percentage of people self-identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) by age group (Based on data from Ref. [51]).

Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) and AIDS

The transmission of infectious diseases remains a major risk associated with sexual relations, producing public health repercussions to an otherwise private act. The CDC estimates that 20 million new cases of STIs are diagnosed every year in the United States, half of which affect those aged 15–24 [52]. The entailing direct and indirect costs are estimated at almost 16 billion dollars [53]. Yet, the exact figures remain difficult to obtain. Not all physicians report STIs, and when they are reported, it is often as individual cases, not as patients. A patient who presents repeatedly with the same infection is reported every time as a new case. Nevertheless, the NHSLS reported that more women (18%) than men (16%) have had an STI at least once in their life. Individuals with multiple sexual partners and those who rarely use condoms are ten times more likely to suffer from an STI than those with fewer or only one partner [8].

When it comes to HIV and AIDS , the highest risk groups traditionally have included men who had sex with men, intravenous drug abusers, their partners and children, and patients who had received contaminated blood products such as hemophiliacs. With drastic measures pertaining to the handling of the blood supply, the risk associated with the last group has decreased significantly. In 1993, the NHSLS reported that 27% of people who were at risk said that they had been tested. Those who were tested tended to be younger, more educated, and living in larger cities. According to NHSLS, 30% of people who were at risk of contamination admitted to have modified their sexual behaviors. Those tended to include younger individuals and those living in larger cities. African Americans and Hispanics were more likely to have been tested and to have changed their sexual behaviors than Whites. Twenty-three percent of married respondents reported being tested and only 12% of them changed their behaviors [22].

Two decades later, looking at the use of condoms during the past ten sexual encounters, NSSHB researchers found that the rate of use was higher in men (22%) than women (18%). Adolescent men (79%) and adolescent women (58%) had a particularly high rate. Condom use was highest among singles (47% of past 10 events), followed by single people in a relationship (24%), with married adults trailing behind (11%). On average, among all non-married adults, condoms were used 33.3% of past 10 events. When broken down by racial group, the rate of condom use was found to be higher among Black (31%) and Hispanic (25%) individuals than Whites (17%). Twenty-five percent of adult men and 22% of adult women reported using a condom during their most recent vaginal intercourse, compared to 80% of adolescent boys and 70% of adolescent girls. Condoms were used more often with casual sexual partners than with relationship partners across all ages and both sexes [41]. Condoms were on average used 26% of the past 10 anal intercourse events (both receptive and insertive) by men and 13% by women [37]. When asked about their most recent sexual encounter, 38% of heterosexual men who reported anal intercourse with a female partner used condoms, lower than 62% of homosexual men [40]. In adult men, those with a higher education used condoms more consistently, single men used them more consistently than married men, and Hispanics used them more consistently than other ethnic groups. In adult women, higher education, single status, and African American race were predictors of more frequent condom use. Men and women who reported a lower number of previous intercourse experiences with the partner and were not using other forms of contraception tended to use condoms more frequently. When it comes to anal intercourse, homosexual and bisexual men used condoms more consistently than heterosexual men [40]. Twenty-six percent of men and 22% of women used condoms during their most recent vaginal intercourse . More than half reported their most recent sexual partner was a relationship partner. Condom use was associated with fewer number of previous intercourse experiences with the partner and not using other forms of contraception for both men and women. Interestingly, condom use was not a significant predictor of pleasure, arousal, erection or lubrication, pain, or eventual orgasm for the participant or his or her partner [41].

A particularly noteworthy finding by the NSSHB was that the rate of condom use among adolescents was on the rise. In 2001, the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) data revealed that 65% of male adolescents and 51% for females reported condom use during their last intercourse [54]. In comparison, the NSSHB figures, published in 2010, were 79 and 58%, respectively [43]. In 1988, 53% of 17-year-olds used a condom during their last vaginal intercourse [55]. The figure rises to 65% of 12th graders in 2009 [56]. In the NSSHB, 80% of males that age reported condom use during their last vaginal intercourse [43]. The authors concluded that this may have been due to public health efforts to encourage condom use [43]. However, rates of condom use are lower in young adults, suggesting that more effort should take place at educating those transitioning from adolescence to adulthood regarding maintenance of condom use, given that this may be due to entering short- and long-term relationships at this age [41].

The NSSHB reported that condom use with casual partners was lowest among men and women over the age of 50 [41]. Two thirds of men over 50 reported that they did not use a condom during their last sexual encounter. About 20% of men and 24% of women reported condom use during the last sexual encounter. This figure fluctuated depending on partner type, as men used condoms most frequently with a sex worker and women with a friend. These findings, the authors conclude, speak to the need to promote its use in this cohort, given that sexual lives are now being extended thanks to pharmacology and that the risk of sexually transmitted illnesses remains [41]. It is nowadays common for older adults to have new sexual partners, given that their old partners could be lost to divorce, death, or serious illness. Even though pregnancy may not be a concern in this age group, the risk of infection still is. The authors of the study conclude that providers should be attentive to the sexual behaviors of older patients, especially with regard to sexually transmitted infections, and that this age cohort should increasingly be the target for sexual health education (Figure 3-4).

Prevalence of Sexual Disorders

Sexual disorders are disturbances in the psychophysiological changes related to the sexual response cycle in men and women [57]. They have a relatively high prevalence in the US population [58], as suggested by the ubiquity of the advertising for pharmacological remedies such as erectile dysfunction. However, the scarcity of large-scale epidemiological data has led researchers to rely on integrating the data from smaller studies [59]. The most important recent set of data on the topic derives from the NHSLS [60] and is cited extensively in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th edition (DSM-5) [57] as well as in this section.

Male Sexual Dysfunction

The exact prevalence of erectile disorder is unknown. There is a clear correlation between advancing age and increase in prevalence and incidence of erectile dysfunction [61]. Thirteen to twenty-one percent of men aged 40–80 report occasional issues with erections. Two percent of men younger than 40 report frequent issues with erections, compared to 40–50% of men older 70 who have significant erectile disorder [62]. Interestingly, on their first sexual experience, 20% of men feared problems with erection, but only 8% actually experienced an erectile issue that hindered penetration [57]. The prevalence of delayed ejaculation is also unclear, since the syndrome lacks a precise definition [57]. Seventy-five percent of men report that they always ejaculate during sex [60]; however, less than 1% of them report trouble lasting 6 months or more with achieving ejaculation [63].

One Swedish study reported that 6% of men aged 18–24 and 41% of men aged 66–74 report a decreased sexual desire [64]; however, the prevalence of male hypoactive sexual desire disorder varies with both the method of assessment and the country of origin.

Concern with premature ejaculation is reported by more than 20% of men aged 18–70 [65]. However, the actual prevalence of the disorder drops to about 1–3% if the narrow DSM-5 definition is followed (ejaculation occurring within approximately 1 min of vaginal penetration) [57]. Interestingly, men with liberal attitudes about sex were reported to be 134 times more likely to experience premature ejaculation [60].

Female Sexual Dysfunction

The epidemiology for male sexual dysfunction is scarce at best, but the data is even more lacking when it comes to female sexual dysfunction [60]. The prevalence of female orgasmic disorders has been reported as 10–42%, depending on the age, culture, duration, severity, and the method symptom assessment [57, 66]. However, only a fraction of them report distress related to the disorder [67]. Laumann estimates that about 10% of women do not experience orgasm throughout their lifetime [22].

Female sexual interest/arousal disorder is a new entry in the DSM-5, so its prevalence as such is unknown [57]. The prevalence of low sexual desire and of problems with sexual arousal, which was the disorder present in the previous edition, also varies with age, culture, and duration [68, 66]. Again, only a fraction of women with the disorder report distress related to it [69, 70], and although sexual desire may decrease with age, older women often reported less distress related to the lack of sexual desire than younger women [69]. Fifteen percent of North American women report recurrent painful intercourse [60].

Conclusion

The topic of sexual behavior is a complex one, surrounded by a web of cultural and social norms, as well as ancient taboos. Although the sexual act remains one of the most private events, it continues to have major public health repercussions. Given the ever-changing nature sexual practices and the public perception thereof, the gathering of accurate data regarding sexual behaviors remains of utmost importance in order to adequately allocate resources and properly target at-risk populations. Despite the myth to the contrary, recent surveys have shown that “under the proper circumstances, adults in the United States will cooperate in a scientific survey about their sexual behavior” [30].

References

Ohri L. HPV vaccine: immersed in controversy. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(11):1899–902.

Elders MJ. Sex for health and pleasure throughout a lifetime. J Sex Med. 2010;7(Suppl 5):248–9.

World Health Organization. Defining sexual health: report of a technical consultation on sexual health. Geneva; 2006.

Christenson CV. Kinsey: a biography. Bloomington/London: Indiana University; 1971.

Kinsey AC, Mart CE. Sexual behavior in the human male. Bloomington/London: Indiana University Press; 1948.

Kinsey A, Pomeroy W, Martin C, Gebhard P. Sexual behavior in the human female. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1953.

Goldstein I. Looking at sexual behavior 60 years after kinsey. J Sex Med. 2010;7(Suppl 5):246–7.

Michael RT, Gagnon JH, Laumann EO, Kolat G. Sex in America: a definitive survey. Boston: Little, Brown; 1994.

Kinsey AC, Hyman R, Sheatsley PB, Hobbs A, Lambert R, Pastore N, Goldstein J, Terman LM, Wallin P, Wallis WA, Cochran WG, Mosteller F, Tukey JW. The Cochran-Mosteller-Tukey report on the kinsey study: a symposium. J Am Stat Assoc. 1955;50(271):811–29.

Bradburn NM, Sudman S. Polls and surveys: understanding what they tell us. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1988.

Duberman M. Jones: Alfred C. Kinsey. The Nation, p. 40–43, 1997.

England L. Little kinsey: an outline of sex attitudes in Britain. Public Opin Q. 1949;13(4):587–600.

Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human sexual response. Toronto, NY: Bantam Books; 1966.

Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human sexual inadequacy. Toronto, NY: Bantam Books; 1970.

Klassen AD. Sex and morality in the U.S.: an empirical enquiry under the auspices of the Kinsey Institute. Wesleyan: Middletown; 1989.

Booth W. The long, lost survey on sex. Science. 1988;239(4844):1084–5.

Fay RE, Turner CF, Klassen AD, Gagnon JH. Prevalence and patterns of same-gender sexual contact among men. Science. 1989;243(4889):338–48.

Zelnik M, Kantner JF. Sexuality, contraception and pregnancy among young unwed females in the U.S. In: Demographic and social aspects of popultion growth. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1972.

Zelnik M, Kantner JF, Ford K. Sex and pregnancy in adolescence. New York: Sage; 1981.

Mosher WD, McNally JW. Contraceptive use at first premarital intercourse: United States 1965-1988. Fam Plann Perspect. 1991;23(3):108–16.

Gagnon JH, Simon W. Sexual conduct: the social sources of human sexuality. Chicago: Aldine; 1973.

Laumann EO, Gagnon JH, Michael RT, Michaels S. The social organization of sexuality: sexual practices in the United States. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1994.

Athanasiou R, Shaver P, Tavris C. Sex. Psychol Today. 1970;37–52.

Tavris C, Sadd S. The redbook report on female sexuality. New York: Random House Publishing Group; 1978.

Louis Harris & Associates. The playboy report on American men: a survey and analysis of the views of American men in their prime years, regarding family life, love and sex, marriage and children, the “outer” man and “inner” man, drug use, money, work, politics and leisure. Playboy. 1979.

Hite S. The Hite report: a national study of female sexuality. New York: Dell; 1976.

Janus SS, Janus C. The Janus report on sexual behavior. New York: Wiley; 1993.

Greeley AM. Janus report. Contemp Sociol. 1994;23:221–3.

ABC News. The American Sex survey: a peek beneath the sheets. 2004.

Michael RT. The National Health and Social Life Survey: public health findings and their implications. In: To improve health and health care. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1997.

Cooks R, Bauer K. Our sexuality. Belmont: Thomson Wadsworth; 2010.

Warren C, Santelli J, Everett S, et al. Sexual behavior among US high school students. Fam Plann Perspect. 1998;30(4):170–172, 200.

Santelli J, Warren C, Lowry R, Sogolow E, Collins J, Kann L, Kaufmann R, Celentano D. The use of condoms with other contraceptive methods among young men and women. Fam Plann Perspect. 1997;29(6):261–7.

Santelli J, Lowry R, Brener N, Robin L. The association of sexual behaviors with socioeconomic status, family structure, and race/ethnicity among US adolescents. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(10):1582–8.

Suzman R. The National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project: an introduction. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64B(Suppl 1):i5–i11.

Reece M, Herbenick D, Schick V, Sanders SA, Dodge B, Fortenberry JD. Background and considerations on the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior (NSSHB) from the investigators. J Sex Med. 2010;7(Suppl 5):243–5.

Herbenick D, Reece M, Schick V, Sanders SA, Dodge B, Fortenberry JD. Sexual behavior in the United States: results from a national probability sample of men and women ages 14–94. J Sex Med. 2010;7(Suppl 5):255–65.

Wylie K. A global survey of sexual behaviours. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2009;3(2):39–49.

Herbenick D, Reece M, Schick V. Sexual behaviors, relationships, and perceived health status among adult women in the United States: results from a national probability sample. J Sex Med. 2010;7(suppl 5):277–90.

Reece M, Herbenick D, Schick V, Sanders SA, Dodge B, Fortenberry JD. Condom use rates in a national probability sample of males and females ages 14 to 94 in the United States. J Sex Med. 2010;7(suppl 5):266–76.

Sanders SA, Reece M, Herbenick D, Schick V, Dodge B, Fortenberry JD. Condom use during most recent vaginal intercourse event among a probability sample of adults in the United States. J Sex Med. 2010;7(suppl 5):362–73.

Reece M, Herbenick D, Schick V. Sexual behaviors, relationships, and perceived health among adult men in the United States: results from a national probability sample. J Sex Med. 2010;7(suppl. 5):291–304.

Fortenberry JD, Schick V, Herbenick D. Sexual behaviors and condom use at last vaginal intercourse: a national sample of adolescents ages 14 to 17 years. J Sex Med. 2010;7(Suppl 5):305–14.

Lewes K. The psychoanalytic theory of male homosexuality. New York: Simon and Schuster; 1988.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1952.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1968.

Drescher J. Out of DSM: depathologizing homosexuality. Behav Sci. 2015;5(4):565–75.

Marmor J. Sexual inversion: the multiple roots of homosexuality. New York: Basic Books; 1965.

Marmor J. Homosexual behavior: a modern reappraisal. New York: Basic Books; 1980.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1980.

Gates GJ, Newport F. Special report: 3.4% of U.S. adults identify as LGBT. 18 Oct 2012. [Online]. http://www.gallup.com/poll/158066/special-report-adults-identify-lgbt.aspx. Accessed 18 Sept 2016

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2014. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2015.

Chesson H, Blandford J, Gift T, Tao G, Irwin K. The estimated direct medical cost of sexually transmitted diseases among American youth, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;41:217.

Anderson J, Santelli J, Morrow B. Trends in adolescent contraceptive use, unprotected and poorly protected sex, 1991-2003. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(6):734–9.

Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL, Ku L. Changes in adolescent males’ use of and attitudes toward condoms, 1988-1991. Fam Plann Perspect. 1993;25(3):106–10.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2009. MMWR 2010;59:1–142

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

Spector IP, Carey MP. Incidence and prevalence of the sexual dysfunctions: a critical review of the empirical literature. Arch Sex Behav. 1990;19(4):389–408.

Simons J, Carey MP. Prevalence of sexual dysfunctions: results from a decade of research. Arch Sex Behav. 2001;30(2):177–219.

Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281(6):537–44.

Lewis R. Epidemiology of erectile dysfunction. Urol Clin North Am. 2001;28(2):209–16.

Prins J, Blanker M, Bohnen A, et al. Prevalence of erectile dysfunction: a systematic review of population-based studies. Int J Impot Res. 2002;14(6):422–32.

Mercer C, Fenton K, Johnson A, et al. Sexual function problems and help seeking behaviour in Britain: national probability sample survey. BMJ. 2003;327(7412):426–7.

Fugl-Meyer A, Sjögren Fugl-Meyer K. Sexual disabilities, problems and satisfaction in 18-74 year old Swedes. Scand J Sexol. 1999;2:79–105.

Laumann EO, Nicolosi A, et al. Sexual problems among women and men aged 40–80 y: prevalence and correlates identified in the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behavior. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17(1):39–57.

Graham C. The DSM diagnostic criteria for female orgasmic disorder. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39(2):256–70.

Oberg K, Fugl-Meyer A, Fugl-Meyer K. On categorization and quantification of women’s sexual dysfunctions: an epidemiological approach. Int J Impot Res. 2004;16(3):261–9.

Brotto L. The DSM diagnostic criteria for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39(2):221–39.

Bancroft J, Loftus J, Long J. Distress about sex: a national survey of women in heterosexual relationships. Arch Sex Behav. 2003;32(3):193–208.

Dennerstein L, Koochaki P, Barton I, Graziottin A. Hypoactive sexual desire disorder in menopausal women: a survey of Western European women. J Sex Med. 2006;3(2):212–22.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Tobia, G., Chahal, K., IsHak, W.W. (2017). Surveys of Sexual Behavior and Sexual Disorders. In: IsHak, W. (eds) The Textbook of Clinical Sexual Medicine. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52539-6_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52539-6_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-52538-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-52539-6

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)