Abstract

After the total governmental control of the urban transport systems during the Soviet epoch came the 20 year long period of almost complete deregulation. Currently there is a trend towards the return to the practice of formal urban transport management, which represents a strange mixture of the remnants of the Soviet methods and the selective adoption of western urban planning practices. The chapter highlights the institutional aspects of transportation systems design and functioning. Using the neo-institutional approach, authors analyze urban transportation system management institutions as well as transportation policy of Russian authorities. The presented analysis consists of two levels: macro-level reveals trends at institution design, explains path dependency from the Soviet epoch. The micro-level put the light on the issue of decision design and the influence of certain actors. The clarification of the formal and informal urban transport management requires the overview of the following questions: the interests and the principles of authorities and private operators’ interaction, practices of transport demand management implementation and public reaction, the evolution of public perception of private and public property. The chapter is organized as follows. The first, introductory part of the chapter is dedicated to explaining the approach and methodological framework used. The second part reveals peculiarities of Soviet transportation system heritage. The third part examines the challenges of 90s period—introduction of free market mechanisms and era of deregulation. Fourth part discusses the experience of the first decade of 21th century and relevant changes in transport system. In the final part authors analyze main institutions; both formal and informal which shape the modern transport system.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

6.1 Introduction

The search for an optimal configuration and management mechanisms of a transportation system is heavily dependent on the thorough analysis of the examined system and conditions under which it is functioning. Transportation system of modern Russia is a very complex one—based on Soviet fundament of centralized planning, after undergoing the “wild market” period in 1990s it is making steps towards era of sustainable mobility. Nevertheless, the system functioning and further development depends on many factors of a different kind—political, economic and social that define results and effectiveness of any reforms undertaken in the transportation sector.

Unfortunately, opposite to studies conducted abroad (Prybyla 1966; Grieco 2011; Kolik et al. 2015) the contemporary literature lacks studies of Russian transportation system in means of institutional approach. The approach allows to investigate key pillars that shape the system, reveal its possible points of development and problematic spots that needs attention. Big Russian cities like Moscow and Saint-Petersburg face transportation problems that some countries have already solved. But on the other hand, blind import of successful practices can be nonresultative due to specific context under which the systems exist. Still, the study of Russian experience can be useful for developing countries that are undergoing processes of reforming the existing system of transportation.

The presented chapter focuses on investigating formal and informal institutions that poses influence on Russian transportation system as a whole and local systems as well. In the first, introductory section we describe the theoretical approach used. The second section discusses the Soviet heritage that mainly shaped transportation system of modern Russia. In the third section we discuss issues of the transitional period—1990s, when market mechanisms started functioning under the new political and economic regime. The fourth section is dedicated to analysis of the modern period, after 2000, revealing recently formed trends that shape the state-of-art Russian transportation system. In the last, fifth section we present in-depth analysis of institutions and actors that pose influence on transportation system functioning, and give examples of their influence.

Theoretical framework

Defining an institution is not a simple task due to a huge legacy of institutional studies. Despite the multidisciplinary nature of institutional studies, the most concentrated and thus fruitful research efforts (including adaptation) were made within political science. That is quite understandable as political institutions shape not only the political rules of the game, but indirectly economic (North 1990; Acemoglu et al. 2005; Hodgson et al. 2006) and social institutions.

The only reason to consider institutional impact on the public policy and its specific areas such as urban transport management is that institutions either shape ‘the rules of the game’ or are ‘the rules of game’ themselves. Having a thesis “institutions matter” as a starting point of this discussion, we would like to take an excursion into the institutional theory in order to answer the question “why do institutions matter?”

Why institutions matter?

First, because institutions are established ‘rules of the game’ enforced and maintained by actors’ behavior, identities, and repertoires. Second, because one incorrect institutional choice can put an end to the system’s development or put clock back for years. Third, because institution determines the sequence of participation (e.g. voting) and procedure of decision-making process; and assigns power, resources and authority to certain positions and roles. Institutions indirectly determine an outcome of any given decision-making process by shaping incentives and opportunities for actor’s behavior, and establishing and promoting evaluation criteria. Fourth, institution is not limited to formally structured rules of game, but also consists of ideas, norms, cultural conventions and cognitive frames that provide actors with meaningful information for interpreting the context. Even if the formal rules are changed, the ideas behind them might stay the same. Actors are trapped in the same logic of context interpretation, do not change their behavior and neglect the changes in formal rules. Fifth, institutions matter because they form, maintain and advance the relationship between actors, giving them advantageous positions for resource extraction, moderation of agenda setting and so on.

Theoretically described role of institutions in shaping actors’ behavior and decision making process has a number of practical implications. The very first one is Hall’s royal road to identification of institutions. Hall introduced a concept of Standard operation procedures (SOP) (Hall 1986) that are specific rules of behavior that are agreed upon and followed (in general) by agents, whether explicitly or tactically agreed (Rothstein 1996). Therefore, SOP unites notions of formal and informal institution, but distinguishes institutions from broader and more personally related categories like habits or customs.

Before describing how institutions work and how they manage to impose constraints on actors’ behavior in details, we should briefly discuss the nature of these constraints. Generally institutions in public policy perform their action-changing role through rules, practices and narratives. Rules are the engine of formal institutions, they are officially constructed and sanctioned by coercive actions and formal rewards and punishments. Rules are ‘stable means of making choices’ (Peters et al. 2005) that mainly creates procedures of decision making. Rules implementation is the key issue determining the effectiveness of formal institution. If rules are routinely enforced and individuals generally comply with them, formal institutions are considered to be effective. Opposite case—where noncompliance appears frequently and is usually left unsanctioned—is a sign of weak institutions and a wakeup call of state having dysfunctional institutional system.

Practices constitute and maintain informal or unstructured institutions that lack means of coercive actions. They are ‘ways things are done around here’ that are not officially recorded of sanctioned. Practices are disseminated through demonstration of what is considered to be a proper conduct. Despite informal nature and lack of coercive means of implementation practices are powerful means of institutional pressure that can help maintaining formal institutions or contradict them (Helmke and Levitsky 2003).

Alongside with formal rules and informal practices, institutions constrain actors’ behavior via narratives. Narrative is defined as a “sequence of events, experiences, or actions with a plot that ties together different parts into a meaningful whole” (Feldman et al. 2004). Narratives are about explanation, persuasion and legitimation (or delegitimization) of current rules and practices. They reinforce norms (both formal and informal) through cognitive framing that creates shared understandings of ‘why the things are done this way’. Narratives play an important role in maintaining institutional design in the long term prospective.

How do institutions influence public policy?

First of all, institutional design that shape incentives and opportunity and evaluation criteria for actor’s performance also revises strategic goals set by the elite.

Second option for institutions to constrain public policy is by determining who and how can make decisions.

Thirdly, alongside with determining how decisions are taken, institutions shape public policy by establishing rules and practices of the ‘influencing game’. Institutions provide incentives and opportunities for interest groups to influence the political decision making process. Institutions not only distribute public resources in a way to create and support certain interest groups, but also maintain political opportunity structure and veto points.

Summing up, institutions matter in the public policy formation and implementation, because they not only shape rules and procedures of any decision making process, but provide interest groups with resources and frame lobbying opportunities. In other words, lobbying success cannot be only attributed to the interest group’s resources or solely to the current configuration of political institutions within political opportunity structure, open or closed to pressure efforts. Previously discussed ‘veto points’ determine how interest groups could influence policy outcomes. Shaped by the institutional design and current electoral results, veto points provide lobbying opportunities for interest groups (Immergut 1990).

How and when do institutions change?

Since political institutions play an important role in shaping policy decisions in different areas, we should briefly discuss conditions of institutional changes. According to the rich research legacy of the new institutionalisms, institutions are prone to changes (1) under external shocks; (2) through the process of competitive selection; and (3) due to the institutional design (Goodin 1996).

First condition for institutional changes—external shocks—is typically described as ‘critical junctures’ interrupting long periods of path dependent institutional continuity in the standard model of punctuated equilibrium adopted by historical institutionalism. Less radical and more incremental approach to institutional changes suggests that not only external shocks can create disruption in institutional equilibrium, but also internal pressure. Internal pressure for change is caused by enduring gaps between institutional ideals and practices. An example of such internal pressure source is described by March and Olsen (1996): when people lose faith in institutional arrangements, they switch from rules to standard operation procedures and further more. This reallocation of resources reduces the ability of institutions to enforce the rules and increases the capacities of alternative structures, thus promoting institutional changes.

Competitive selection is a term coined to describe a competition of different institutional elements (rules, routines, etc.) for survival and reproduction. Competitive selection states that there are no ‘immortal’ institutions over time, instead an ever-changing mix of rules exists and structures actors behavior in any given moment.

The processes of change attributed to institutional design take place if actors specify design in order to achieve some objectives (for example, constitutional reform weakening the executive branch by redistributing powers to legislature). Another reason for this type of changes is conflict design, the one that reflects the result of a bargaining game between different actors pursuing conflicting goals; or learning, which perfectly fits the ‘import reform’ cases—when actors borrow from others or adapt design with the most appropriate feedback results (March and Olsen 2006).

6.2 Urban Transport in USSR in the 1980–1990s

The Soviet administrative system of the urban transport systems has passed through numerous and very contradictory transformations in the 1930–1980s, so by the time of the communistic system break-up it was organized in the following way.

The property complexes of all transport branches were in the state ownership, each transport entity was under direct administrative supervision of the relevant ministry or department. The entities were functioning on the basis of the state plan which was set in the natural indicators (the number of the transported passengers, the amount of the transported freights, the amount of transport work formulated in passenger- and tonne-kilometers). Such indicators like the income, the expenses, including the labor costs, the labor productivity and the output per unit of vehicles or per capacity unit (the load-carrying capacity) of public transport vehicles were also preplanned. At the same time the transportation tariffs were fixed in the centralized way, and the government carried out the deliveries of public transport vehicles according to the centralized formalized rules connected with the standard rates on the updating of the vehicle park and the accomplishment of the target figures.

The railroads were under authority of the Ministry of Railways of the USSR, in particular:

-

the entities of the rail transport which carried out the transportation of life-support goods for the urban population and the operation of the industrial enterprises;

-

the suburban railroads which served the suburbs of the majority of the large cities of the country.

-

the subways.Footnote 1

The decisions on the construction of the subways were prepared at the level of the party leaders of the corresponding republics or regions, as well as they were to be coordinated in the key allied departments (A State Planning Committee of the USSR and the State Committee for Construction of the USSR) and be finally approved at the level of the top party management.

The Soviet subway and first and foremost the Moscow subway were a classic for the Soviet practice example of contradiction between «in nominal» and «in real». «In nominal» the Moscow subway is an efficient transit system with the exceptionally high freight capacity and the speed of traffic. «In real» it was an exhibition of achievements of Soviet culture (the outdoor pavilions and underground subway lobbies were designed by the best architects and interiors were decorated by the first-rate artists) and, at the same time, the structures for mobilization purpose. The first circumstance led to the situation when the development of the subway network was always sacrificed to create the next installation of the monument of Soviet architecture. The second one led to the choice of decisions on design that are uncommon to the international practice of the subway construction. Moscow metro lines (that were constructed in 1930–1960s) are traced in deep tunnels. The distance between the stations is so great that the trips from the suburbs to the center, as a rule, are bimodal: the destination has to be reached by the land transport.

The tramway depots and the trolleybus parks were under authority of the republican ministries of housing and communal services (Minzhilkomkhoz), the largest of which was one in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR).

In the cities of Russia which are located on the big rivers, an essential role in the transportation of goods (first of all, the construction freights), and also in suburban passenger traffic was played by the river shipping companies which were under authority of the Ministry of the river fleet.

The public motor transport has been the key element for the most of the cities, and its enterprises were under authority of the profile republican ministries. In point of fact each ministry represented the large state corporation, which was aggregating the professional carriers in segments of the cargo and the passenger motor transport. The largest ministry in RSFSR was the Ministry of the motor transport (Minavtotrans) which was supervising the core management structures in all regions of Russia, besides all the enterprises of the cargo and passenger motor transport, including the bus and taxi fleets were under authority of the Ministry. Concerning the urban areas (the cities) the key element of this system was presented by the bus fleets, the largest of which operated more then 800–1000 buses.

Because of the reason that the profile ministries of the Union were absent, the certain coordination powers on the level of the Union, first of all, regarding the technical and innovative policy, were assigned to the Ministry of the motor transport (Minavtotrans) of RSFSR and the Ministry housing and communal services (Minzhilkomkhoz) of RSFSR.

Some certain exceptions concerning the general management structure of the motor and urban electric transport have been made for Moscow and St. Petersburg. The bus and taxi fleets, the trolleybus parks, the tramway depots, which were united in a single structure—Mosgortrans, remained so far submitted to the city authorities of Moscow. The city authorities of St. Petersburg had the trolleybus parks and the tramway depots under control, while the local association of the passenger motor transport (Lenpassazhiravtotrans) remained in subordination of Minavtotrans of the RSFSR.

The system of the centralized directive planning of the gross measures promoted obviously a weak interest of the transport entities to satisfy the needs of the transport service consumers and an active interest in the «statistics fraud».

It is necessary to stress that transport planning (with the pure market grounds and the orientation on the demand) is arranged by the principle of ex ante while by its definition the centralized directive (in other words—socialist) planning is arranged according to the principle of ex post. The best of the passenger transport entities had quite good standards of the transport planning and were able to plan route schedules and to arrange the route network properly on the basis of the regular surveys of the transport demand. All of the passenger transport entities had the directive planned indicators on the amount of transport work expressed through passenger-kilometers: it is clear, that the directive indicators have to be simple and additive, in other words, suitable for the addition on the basis of the subordinate entities in total. It was difficult to combine the fine points of the transport planning with the directive indicators, and sometimes it was practically impossible. Meanwhile, the implementation of the directive planned targets was considered to be imperatively necessary: the resources, first of all, the motor fuel were allocated to the entities strictly «in line with the plan»; the deliveries of the new buses have been also connected with the accomplishment of the plan (the new vehicles instead of the disposed ones); the employee bonuses as well as the promotion track in the entities were also depended on the result of the plan’s realization. It was only the number of the passenger claims to be dependent on the fulfilment of the transport planning parameters.

The tariff rates of the passenger traffic were strictly made-up and were maintained at the extremely low level due to the political populism. Thereafter, the financing system of the passenger transport entities was based on the centralized grants and/or the cross subsidizing (in other words, the income was redistributed from the profitable kinds of transport, like the cargo, the passenger long-distance and the charter transportation,—to unprofitable ones, like the urban and suburban transport).

The first option was typical for the bus fleets in the big cities where the main activity was presented by the transportations on regular city routes. The second option was used on a mass scale by the peripheral territorial associations including the carrier entities which were carrying out both cargo service and passenger traffic by all means of transport. Both the centralized grants, and the mutual settlements of accounts within the cross subsidizing have been subordinated to accomplish the directive plan.

The implementation of the directive plan for the bus transport entities was determined, firstly, by the unique objective parameter—the number of the transported passengers that was estimated by the number of the sold tickets, and secondly, by the two relative parameters—the number of the transported passengers groups entitled to the special benefits (free ride), as well as the average trip distance. In these conditions the entities had no serious incentive to respond to the demand, notably to carry out the route schedules properly, especially in hours of the passenger traffic recession. However there were extremely strong incentives to overstate the number of «preferential» passengers and the average range of a trip, this fact led to the regular falsification of the inspections results.

The impetuses to overstate the number of trips were also quiet strong on the lower level where the driver negotiated with the tariff controller for a reasonable fee. Both contracting parties were aware that the top-management won’t demand the clear data (the implementation of the directive plan does not depend on the accomplishment/cancellation of the trips). Besides at the same time the statistics fraud of the number of the trip could provide the driver an extra award, as well as the remained fuel could be used to make a little money on the side. Usually the trips with a small passenger traffic during the interpeak time-periods were not performed in line with this algorithm (however they were included in the report). Moreover such trips were not able to be excluded from the transport planning document (the route schedule): the official of the town council while approving the schedules would always raise objections: «The communist party teaches us to increase the level of the transport service of the population!». The problems of the work disruption and the statistics fraud on the trips quantity became large-scale in the second half of the 80s, so that the Ministry of Transport of RSFSR has issued a special order demanding the 100 % fulfillment of trips from the subordinate carrier-entities (RSFSR Ministry of motor transport order 1987).

The statistics fraud concerning the cargo work was carried out even in a more simple way: for example, the transportation of the cargo which hasn’t got any receiver in interest (garbage, snow) allowed «to improve» the figures in the reports at the end of the planned year or quarter.

These total falsified data was accepted for true on default and was used in order to form the wide and multilevel informal communication in line with the connection «an entity—the territorial association—the ministry—the budget departments of the RSFSR and the USSR». The matter of this communication was the exchange of the resources distributed in a centralized way for some career bonuses and some personal benefits of all the participants of this connection-chain: from the local «commanders of production», to the high-ranking officials distributors. However, the same or the similar «system of the hierarchical biddings» occurred in other industries of the economy (Gaidar 1990).

The most active actor of such communication was the establishment of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), especially on the upper levels of the bureaucratic ladder: the head of the regional transport management who was holding an influential post in the party hierarchy at the same time had good chances to receive the new buses than his colleague—the «ordinary» member of CPSU without any party position.

It is important to emphasize that apart from the public motor transport, there was a large park of cars and buses which was under authority of other institutions not presented by the transport ministries and departments. In the public documents the terms like «the department-level cars (buses)», «the cars (buses) of non-general use» were commonly used.

Till 1991 the number of park of the department-level cars and buses was considered as the information prohibited from publication in the open sources. In order to illustrate the state of things we will provide the table (Table 6.1) from the official statistical digest.

It is necessary to draw attention that the number of cars of the general use (trucks, pickups and passenger vans), and also the public buses appears in the official statistics accurate within the vehicle, while the number of «cars (buses) of non-general use» does not appear at all.

The experts made an indirect assessment of this data in terms of the number of cars (buses) which were produced in the Soviet factories. Also they took into account the dynamics of the allowances, this data was provided by the reports of the public enterprises. According to the Table 6.1, as of 1990 the number of public buses made in the USSR was about 310 thousand units. Judging by the indirect estimates, the number of so-called «departmental-level buses» was no less than 1 million units. The ratio between the nondefense trucks of the general and non-general use is approximately the same.Footnote 2

Most of these «department-level» trucks and buses were possessed by the large industrial enterprises. The buses were used in order to serve the daily cooperative trips for the employees on a route «the residential community—the enterprise’s entrance», as well as to provide for the numerous collective events (typical for the socio-political background of the Soviet period) like the collective farm works,Footnote 3 the cultural, sports or political events. The department-level trucks have been included in the production process of the same industrial enterprises. These vehicles as well as the department-level buses had the two most important advantages over the cars and the public buses:

-

They hadn’t got to deal with the state plan on the tonne-kilometer or passenger-kilometer transport work, thereafter, they hadn’t to make the extra transport work;

-

they were always just in time at the disposal of the user in interest.

The administrative efforts to transfer the departmental park partly in the ownership of the system of the public transport and/or use it on the regular route transportations were made up to the end of the 1980s.Footnote 4

These efforts were met with a latent, but tough resistance from the heads of large enterprises and the relevant industrial ministries. This confrontation has been connected with the fact that the leaders of the Soviet industry had a sufficient real notion of the quality of the Soviet public transport. The real state of the work was radically different from the ceremonial reports which were included in the official reporting and, especially, in the sphere of public propaganda, as well as the materials which were regularly sent to UITPFootnote 5 by the Soviet institutions.

If one makes an objective comparison of the Soviet public transport with the best world analogs, the preference will be given to the latter. The data on the quality of public transport services on the Moscow routes was published soon after fall of «censorship curtain» at the end of the 1980s (Blinkin et al. 1988) (the data is provided in the Chap. 3). These data demonstrate a true ratio of the advantages of «socialist» and «bourgeois» public transport.

It is important to emphasize the following two circumstances. First, the order to carry out an independent and objective examination of the transportation conditions on the Moscow routes in 1986 proceeded from the main Russian reformer—Boris Yeltsin appointed at that time to a position of the party leader of Moscow. In other words, the declaring of the thesis «the emperor is naked» required permission of very high level.

So, the Soviet public transport was considered by John Kenneth Galbraith in his classical monograph (Galbraith 1973) to be one of the acceptable elements of the propagandized «new socialism». The famous scientist Vukan R. Vuchic, the author of the high-quality monograph «Transportation in Livable Cities», published in many countries, saw the Soviet public transport as a positive example of the solution of urban transport problems. Alas, the Soviet myths were much more durable, than the Soviet Union itself.

It is arguable that one of examples of the informal management practices in a transport complex were the running of the truck and bus fleets by the industrial enterprises, as well as the persistent unwillingness to devolve them to the general transport system. These informal practices were getting on with the Soviet centralized administrative system.

The segment of motor cars has been arranged in the most exotic way as compared with the modern reality. In this book we have already emphasized the extremely low level of car ownership in the Soviet cities. This was the result of the fact, that a «sector A» (the heavy and defense industry) was prior over a «sector B» (the consumer goods), and was supported in many respects due to the ideological reasons.

In the 1980s the level of car ownership has doubled due to the volumes of domestic production,Footnote 6 as well as due to the «grey» import market of the used cars which appeared after the adoption of «The law on cooperation». But, even taking into account the rapid automobilization growth, in 1990 there were 80 cars per 1000 Soviet residents that corresponds with the indicators of the Western European countries in the beginning of the 1950s, or the indicators of the USA of the end of the 1910s. It is clear, that in the mentioned conditions the segment of cars did not play a noticeable role in the structure of the urban mobility. Besides the activism of the car drivers did not extend to the problems greater than the questions of the collective parkings.

The directive socialist planning extended even to a segment of the taxi transportations which had and still has strictly market ground. The Soviet taxi drivers were protected from the competition with the private carriers: in 1928–1988 in the USSR the self-employed taxi-driving was considered as an administrative violation. The behavior of the Soviet taxi driver was determined by the combination of directive planned targets (for example, coefficient of paid mileage) and the need to maximize the personal income in the conditions of a monopoly position in the market and the assured (non-market) provision with fuel.

It is to mention a segment of the «company-provided cars» as a very exotic practice. The nominal, or the reflected in official statistics number of the park of such cars made about 500 thousand units in the 1980s, that is 3–4 times more, than quantity of the taxi-cabs. Taking into account features of the statistical accounting of the department park of cars, there is a good reason to believe, that the number of such cars was not less than 1 million.Footnote 7 The term «official cars of uncommon use», represented the cars with a driver carrying the Soviet and party chiefs, and also heads of the large enterprises and the organizations.

The reason why this outmoded institute was saved in the country declaring the socialist ideals was clear not only to experts, but even to the top management. In 1988 the Council of ministers of the USSR issued the resolution «On regulating the use of official cars» (Postanovleniye Soveta Ministrov SSSR (USSR Council of Ministers order) 1988) which appealed to economy and replaced such kind of cars with the compensation payment. In the same 1988 the Ministry of Finance of the USSR issued the guidance letter with a certain amount of compensations (Ministry of Finance of the USSR 1988). However, these documents, as well as many other government documents in the 1980s had no significant effect on transport behavior of the Soviet elite. It must be noted, that nowadays after thirty years of «radical economic reforms» the transport behavior of the postsoviet elite remains just the same as at that time; the changes have concerned only brands and models of cars.

This complicated combination of the formal and the informal institutions, the nominal and the real goal-setting was keeping a certain stability due to the following circumstances.

In general the national economy had a sufficient resource to maintain the city transport systems in the condition acceptable for a very unspoilt Soviet citizen.

The resource allocation with all the «advantages» of the formal and informal practices described above, was adjusted and quite predictable; in any case, the chief of any level was aware of what share he will receive. The skilled worker—the bus driver—also understood that in all cases he will get an acceptable salary.

During «Gorbachev reforms» there were attempts to improve this system in line with the ideas of the «market socialism». There are different points of view concerning whether it was possible to modernize the system of urban passenger transportation within the constant socio-political status quo. However, the happened events violated the first of the above-mentioned conditions: the country ran out of the resources, needed for maintenance of any life support systems. The situation was described by Gaidar (2010): «… the break-up of the socialist system was predetermined by basic characteristics of the Soviet economical political system: the institutes established at the end of 1920s—the beginning 1930s were too rigid and didn’t allow the country to adapt to challenges of the world development at the end of the 20th century. The heritage of socialist industrialization, abnormal defense burden, a serious crisis of agricultural industry, a noncompetitiveness of the processing industries did the break-up of the regime inevitable. In 1970s—the beginning of the 1980s these problems could be regulated at the expense of the high oil prices. But it is unreliable ground to save the last empire».

6.3 The Urban Transport in 1990s

The fundamental changes which had happened in Russia at the beginning of the 1990s, concerned the urban transport systems in full.

The key aspects of these changes are reflected in the well-known presidential decree (Ukaz Prezidenta Rossijskoj Federacii (RF Presidential Decree) 1991) of B. Yeltsin which has been issued in December 1991, almost immediately after signing the Belavezha Accords which declared, that “the USSR, as a subject of international law and a geopolitical reality, is ceasing its existence”.

The decree No. 341 has proclaimed, in particular, the obligatory privatization of the motor transportation entities in the second half-year 1992. In reality this regulation needed many years to be accomplished: even by the end of the 1990s about 30 % of the public road transport entities remained in the municipal property, or in the state-owned property of the federal subjects of the Russian Federation.

The privatization process of the taxi parks was carried out much faster; this process added up to the distribution of second-hand taxi-cars to the drivers as well as the land and the production rooms were restructured for the different business branches. Consequently the taxi transport as the centralized city service went practically out of existence as the subject of the urban reality. At the same time, this developed an almost non-regulated market of the private carting. Among its participants there were not only the former employees of the taxi parks, but numerous motorists of the different specializations (the private carting has replaced their former work, which was lost due to the closure or the restructuring of the Soviet entity).

The post-privatization destiny of the cargo entities depended on their location. The areas of the entities located in the nearest suburbs were much more valuable asset, than old cars and equipment for their servicing and maintenance. Therefore, such entities have been closed, and their land areas were used for construction. The new owners and managers of other cargo entities looked for suitable market niches; the success of these searches was various.

Later some Russian and foreign authors have criticized the process and the results of privatization in the 1990th: «the transformation of property didn’t get the production moving, as the entities went for peanuts not for purpose of the production» (Luneev 2005), and «the main beneficiaries of privatization were presented by the rest of the old bureaucratic establishment and profiteers in order to make easy money» (Evans 2011).

Concerning the transport entities which were initially declared to be privatized in an obligatory way (the cargo carriers and the taxi parks), this criticism looks extremely naive. The planned land use led to the fact that the specified entities often occupied the vast pieces of extremely attractive urban or suburban lands. One was able to keep these areas for the same «the production purposes» like before the privatization only in the conditions, which allowed to maintain the Soviet model of the land use. Moreover, «the production purposes» of the Soviet entities of the cargo transport and the taxi parks could make any sense only in the conditions of the permanent made-up deficit of the transport services offer and the statutory bar, which canceled the private carting and the ownership of the cargo vehicles for private individuals. Thereafter, it is difficult to consider those new owners as «profiteers», who have decided to close such entities and to sell the parcels of land to representatives of violently growing developer business.

The large taxi parks were brought back to life only in the 2010s in a new quality: without any extra land, without their own service base, without any constant staff, besides, concerning the technological formats they were compatible in framework of the «Gett» and «UBER» century.

After the privatization the city entities of the cargo motor transport continued to function successfully, but only when the new owners understood that the scenario «to boost the efficiency of the entity» used to have the NPV (net present value) better compared with the scenario «the liquidation and selling of the land». The first scenario was achieved by the «trial-and-error» method while trying to comprehend the microeconomics and marketing fundamentals: the elasticity of demand to a tariff and the price policy optimization in the competitive conditions; the implementation of the «returns to scale» within the competition with the small transportation business; the expansion of the client base and the adaptation of the park structure to the special features of demand; the deliverance from the extra assets and the constant staff, the outsourcing of the technical maintenance, etc. In a word, the efficiency of the entity was increased at the expense of the quite rational business.

It is important to pay attention to one of the above mentioned circumstances: the competition from the small transportation business. It is easy to understand why this circumstance was regarded as sharp in terms of a simple comparison: in 1990 about 12,4 thousand cargo vehicles were in the private property, after 25 years of the exponential growth this indicator reached 3775 million units in 2014 (data from Main Directorate for Road Traffic Safety).

In these conditions, even if we take into account the indisputable desire of the new transport enterprises owners «to make fast money», as well as the quite reasonable suspicion about its «bureaucratic» origin, it is possible to call them «profiteers» only in connection with the Criminal code of RSFSR.Footnote 8

Consequently, in the above described segments the officials pursued the policy of the rapid and almost total privatization: besides the privatization of the «old» entities of the Soviet type, both in the segment of the cargo motor transportation and in the taxi services an extremely huge group of the private carriers has appeared. Thereafter, the major shifts occurred: the offer deficit of the transport services has been completely liquidated; the system of the tariffs was made to be based on the balance of the demand and offer.

Certainly, this process was not conflict-free. Since 1990 in political and the expert circles there has been a broad opinion on «plundering of the public property», the selling of the «high-capacity technological base» for next to nothing, the disorganization of «the unitary motor transportation industry», the loss of the «social safeguards of employees», the replacement of the «skilled personnel» by profiteers and «effective managers», etc. In due time professor E. Yasin used to respond sternly: «Nothing was stolen from you, because you had nothing!».

Concerning the informal mechanisms, in the segment of the cargo motor transportations there was not only a normal competitive business, but also the normal labor union structures, which had nothing in common with the Soviet heritage.

The decree No. 341 has ranked the rail transport entities among the objects, which could be privatized only by the resolution of the government of the Russian Federation. The reform of the railroads has been dragged on for many years and is not finished so far. The Ministry of Railways of the Russian Federation (the former Ministry of Railways of the USSR) was reorganized only in 2004, though the privatization wasn’t the key point of the reform, but the functions partition within the public administration (all of them were under the jurisdiction the Ministry of Transport of the Russian Federation) and the business activity which has become a prerogative of the state-owned JSC Russian Railways. The reform of the railway industry was added up to the immediate (since December, 1991) transfer of the underground railway (as well as all other assets of urban passenger transportation) into the ownership of the municipal government.

Subsequently, by the end of the 1990s there was an arrangement of the specialized suburban joint-stock passenger companies with the shareholding of JSC Russian Railways, the regional administrations and (only in the few cases) the private investors.

The nontrivial scenario was carried out in respect to the entities of the land urban passenger transport. These entities were in a state of shock not due to the prospect of privatization,Footnote 9 but because of the absence of the supporting point: the management of any bus (trolleybus) fleet or the tram depot was aware that despite the importance to reach the mutual understanding with the local government, the top-management was found in the branch ministry in Moscow. This patronage actor arranged the regular work checks-ups, raised the level of the executive personnel’s skill managing personnel and gave the directions on tariffs, the transportation rules and the instructions on the technical maintenance of the vehicles. But, the most important is that this patron provided them (on the basis of the mentioned above administrative haggling) with resources, first of all, the vehicles, and also with a regular operational grant.

The Resolution No. 3020-1 adopted by the Supreme Council of the Russian Federation in two days prior to the historical decree on privatization «…On the differentiation of the state-owned property» announced: the traditional branch ministries «as the subjects of economic reality» do not exist anymore. The decree No. 341 has fully confirmed this state of affairs: The ministries which used to be the key control centers of all the assets of national economy are mentioned very briefly and in a slighting way: «… In order to consider the features of the privatized entities the ministries and the departments of the Russian Federation take part in the development of the standard conditions of the conclusion of the privatization bargains approved by the State committee of the Russian Federation on the control of state-owned property. … The ministries and the departments of the Russian Federation can send their representatives the committees on privatization of entities within their jurisdiction».

It is necessary to stress, that the first Government of newly established Russia (after signings of the Belavezha Accords in December, 1991) involved the Ministry of transport of the Russian Federation along with the aforementioned Ministry of Railways. It has been established on basis of the Ministry of the Road transport of RSFSR including the departments of the Ministry of the River fleet of RSFSR and the Ministries of the Highways of RSFSR. In December, 1991 the two former Union ministries of the civil aviation and the marine joined the Russian Ministry of Transport, thus losing their influence to a certain extent.

Nominally the new ministry has received extremely wide powers. In reality the situation was absolutely different. The case is not that the airlines and the large steamship companies have been solving their issues with the government bypassing the new ministry.

On the assumption of the above, the most important thing was that the role of the ministry has been cut to the bone also in the branch of the road and city electric transport. The fundamental innovation was presented in a total absence of a subject of the administrative haggling: in the 1990s the ministry had no resources to support the urban passenger entities.

The relationship between the passenger entities and the new owners (the local administrations) emerged on the following grounds:

-

(a)

The privatization is not allowed: the quarter of the century after the adoption of the decree No. 341, the decisions on privatization have been made in relation to a few number of bus fleets only, while the entities of the city electric transport remained state-owned;

-

(b)

The are the made-up unconditional low tariffs and also the free trips for all the groups entitled to such benefits. As it was already mentioned in Chap. 3, the right of the preferential (free) journey was enjoyed by 27.3 % of all population of the country, in some cities this figure reached 35 % (Rodionov 2005);

-

(c)

The grants on a covering of losses (at least of the preferential transportations) are given «within the limits of the possible»;

-

(d)

In city budgets the investment on the re-equipment of the vehicles are provided rather as an exception, than a standing rule.

The last two items reflect the budget realities of the vast majority of the Russian cities: in the conditions of the permanent budget deficit the support of the municipal carriers wasn’t among the priorities of the city authorities. Moscow and some other largest cities, including St. Petersburg and Kazan, were an exception to the rule.

The processes which were resulted from such strategy are described in detail in Chap. 3:

-

The all-round stagnation of the municipal transport entities;

-

The expansion of the paratransit services provided by the private carriers in the formats like the African jitneys;

-

The radical shift from public transport to private cars.

The main competitive advantages of the Russian paratransit depended on the factors which had nothing to do with the market fair play. The private carriers had no liability to transport the groups of passengers entitled to benefits, but there were good opportunities to avoid taxes at the expense of the unrecorded revenue as well as the savings due to the disregard of the elementary regulations on the technical maintenance and the work conditions of the drivers.

All these questionable advantages were not a secret for the city administrations, however there was a forcible argument in favor of the private carriers: the jitneys (the minibuses) were carrying out the passenger transportations properly and without any municipal grants. The unrecorded revenue also prepared the grounds for the «corruption element».

The educated city officials were aware of the fact that the increasing commuting by the private cars fits badly into the planning parameters of the Russian cities,Footnote 10 besides it is fraught with the permanent jams. However, this was also argued well: the car owners got to work independently and at the same time did not require any budget subsidies. The standard counter-evidence used in the discussions abroad lies in the fact that for the municipal budget it is more profitable to support public transportations, than to respond to the increasing number of the private cars due to the high-cost of road construction. Unfortunately, this counter-evidence was absolutely non-valid for the Russian provincial realities: the road construction was suffering from the deficit of fund just like the support of the municipal carriers.

As a matter of fact the authorities took a laissez-faire attitude towards the situation with the urban mobility: the municipal administrations had no resources to pursue a distinct transport policy, the central power was adhering to the position of the «positive non-interference». This state of affairs can be described as «fragile state», the term used in the political science.Footnote 11

The issue concerning the division of power and responsibility between the central authorities and the local governments deserves more thorough review.

The Constitution of the Russian Federation adopted in 1993 has declared independence of the local government from the state authorities. Their areas of jurisdiction were determined by the Federal Law «On Local Government» (28.08.1995, No. 154-FZ). In relation to the transport policy the law supposed numerous so-called “unfunded mandates” or the expenditure commitments of the local government determined by the federal or regional legislation, but without any sources of their covering.

The area of responsibility of the local government included «the organization of transport service for the population», and also «the municipal road construction and the maintenance of the local roads». The issue of the funding sources, required for implementation of these mandates, has been formulated in a florid way:

-

«The authorities of the local government provide satisfaction of the basic needs of the population in the responsibility areas referred to the municipal divisions at the level above the minimum state social standards. It is guaranteed by the state, federal authorities and authorities of subordinate entities of the Federation by consolidating allocations from federal taxes and dues collected in subordinate entities of the Federation into revenues of local budgets.

The question «What do the minimum state social standards mean?» in terms of the street network and the transport service of the urban population wasn’t clarified during the whole validity period of the abovementioned law. Over the years there was no practice to contribute the federal and regional taxes to the local budgets in connection to the commitments of the local governments to satisfy transport needs of the population.

In spite of the fact, that the ambiguities as well as the evasive language of law were the features of this law, it reflected the political guideline on decentralization in the 1990s and particularly on the relative autonomy of the local government from the federal center.

Concerning the transport issues the law No. 154 provided quite proper ideas:

-

The local government authorities are responsible for a street and road network of the cities and for the provision of the transport service (as well as for some other questions of life support);

-

The federal government authorities set certain minimal social standards of life support;

-

if the city has not enough funds to accomplish these minimum social standards, the authorities of the federal center and the federal subjects of the Russian Federation transfer a certain part of revenue from the federal and regional taxes to the city.

Unfortunately, in reality this system wasn’t working properly, but at least it was considered as quite convincing at the conceptual level.

6.4 The Experience of the First Decade of the 21st Century

By the middle of the Noughties, during the second term of the President Vladimir Putin, the political regime came back to the quite centralized and authoritarian forms of the governance. It was clear that the transition from the Soviet totalitarianism to democracy isn’t an irreversible process (Ottaway 2003); in this regard Russia has shown an example of an «unstable» transformation. The authors which studied this political phenomenon paid attention to such factors like absence of the steady formal institutes (as well as civil informal one) in the transition phase, a sustainable economic development (Evans 2011), as well as a political willpower (Carothers 2002).

The political scientist Th. Carothers describes both the structural and the procedural (relating to the actors’ activity) factors which determine the success and the irreversibility of the transition from autocracy to democracy. The structural factors include: the level of the economic development, the level of the ethnic heterogeneity, the sociocultural factors and the path dependence phenomenon, which is extremely important for Russia concerning the formation of the state and civil society institutes. As regards the procedural approach, the main idea is that, despite the importance of the above-mentioned factors, there is a number of cases when the countries followed the democracy road while lacking for the due structural preconditions. The reason is the political willpower of the elite to move towards the democratic development. When it comes to democracy, “anyone can do it” (Carothers 2002). Unfortunately, the political establishment in Russia hasn’t shown such political will.

Another important issue we need to focus on is the influence of the democratic institutions or their absence (or centralization/decentralization) on the economic development and, particularly, on the development of the urban transport systems.

The Russian experience in the Noughties shows that this influence is very ambiguous. The matter is that in most of the Russian cities on any elections and in any public events the «controlling interest» belongs to the government-financed stratum of the population—such as pensioners, employees of the budget sphere, and employees of the municipal entities. Their political views are determined by the paternalistic values of the Soviet type mixed up with the ideas of the fair division of the income from the oil and gas export.

In this value system there is no place for an idea that the government is no more than a hired manager whose existence depends on the funds of the taxpayers. In addition, there is no principle of the private responsibility of the citizen as a voter and a taxpayer, as well as the understanding on the division of power, and also of limits of the authority on the federal, regional and local levels of the government. Moreover, the representatives of the political establishment are lacking understanding of how the whole system functions.

Experience of the first decade has provided several convincing cases on the subjects designated above. The first one is connected with an attempt of the government to follow the practice of the direct payments, particularly, the monetization of the free trips.

The Federal law No. 122-FZ (August 22, 2004) provided quite reasonable measures to replace the right for the free travel with the direct monetary adjustment. The law was supported not only by the arguments from the liberal economy articles, but also by the common sense:

-

in the beginning of the 2000s the municipal transport entities were functioning with 30–40 % Farebox Recovery Ratio, in addition to that the subsidies from the city budget weren’t able to cover even their straight losses. Respectively, each trip performed on a city route wasn’t able to bring in anything to the carrier, but a dead loss; besides there weren’t any economic incentives to set the buses (or trolleybuses and trams) on routes;

-

Despite the bad financial performance of the municipal transport enterprises, mass corruption was one of the main features of the branch. This was the result of the lack of the credible information on the quantity of passengers with free-trip benefits, and, thereby, there was a complete uncertainty about the pecuniary obligations of the city as a transport service customer;

-

On the merits the urban transport benefits represented a discrimination in relation to the residents of the other settlements which didn’t have any public transport routes.

The law No. 122-FZ made a division of the financial responsibility for the compensations payment to passenger group entitled to the benefits. The persons who received the benefits under the federal legislation shall receive the compensation payments at the expense of the federal budget. Although this regulation seemed quite logical, there was a traditional practice to delegate these commitments from the federal level to the regional and the local ones, which were out of the budget sources.

According to the federal legislation, the passenger group entitled to special benefits included the participants and disabled veterans of World War II, the armed forces personnel, the persons with disabilities and other small population groups. Hereby, the monetization of these benefits didn’t cause some kind of problems for the federal budget. At the same time the regional benefits applied to the veterans of labour and the pensioners that was up to 30 million people. The most of the federal subjects’ budgets had obviously no opportunity to compensate these benefits within reasonable limits.

The public response to the law on monetization of social benefits was unprecedentedly violent. The level of participation in the protest actions was comparable with the revolutionary events in 1991. The protests movement concerned wide sections of the population including pensioners, students and officers. The protesters have blocked the railroads and the highways; they demanded the resignation of the mayors, the governors and the ministers of the economic development. The monetization of social benefits was openly opposed by the heads of regions, the Mayor of Moscow Yu. Luzhkov wasn’t an exception.

Consequently a quite reasonable reform turned into increased budget expenses, a downward rating (however, for short time period) of the federal authority and giving up some key points of this reform. For example, in Moscow there are still free trips with so-called «social cards» for veterans of work, pensioners and some other population groups.

The second case was connected with the introduction in a number of the cities of the country, first of all in Moscow, of the institute of paid parking. This case relating in 2013–2014 is in detail sorted in Chap. 5.

It is important to emphasize, that this quite reasonable conventional measure caused the strong protest moods from the capital car owners, who were presented by the people younger and financially more secure, than the Russian electorate at the average. The public activity of the civil society was reduced by a number of laws and measures of the law-enforcement practice, which were adopted after the rallies against the falsification of the election results. So, the protest against the paid parkings was expressed generally in the social networks and in the form of mass use of various technical devices allowing to avoid the parking charge.

The Moscow administration with its sufficient political stability haven’t made any concessions: the practice of paid parking has been extended to the most of the city areas.

Two more cases which are also described in Chap. 7 are important to be mentioned:

-

the introduction of a toll on federal highways regarding the trucks with an axial load more than 12 tons. The amount of the toll was estimated by the so-called system «Platon», which was an analog of the German system «LKW Maut»;

-

the introduction of the toll road M11 «Moscow-St. Petersburg».

In the first case the protests of drivers of the heavy trucks were so mass and violent that the government was forced to reach a compromise, which reduced the budget effect of the new payment system to zero.

In the second case the protest activity was expressed by the residents of ZelenogradFootnote 12 and the cities of Moscow Area, who had plans to use the section of the new road for their daily labor trips. This activity was latent and didn’t seem as a threat for the federal and Moscow authorities. Nevertheless, the response of the empowered politicians was immediate and especially populist: the government adopted a resolution, which determined the limit size of tariff rates on the toll roads.

All these cases, despite all the economic distinctions and the response of the authorities, reflect the public moods dominating in Russian society. The electorate majority is quite ready to submit any restriction of rights and civil liberties, but will persistently stand up for the free riding right.

Concerning the perspective of the local government, the abovementioned law No. 154-FZ was replaced with the more completed legal act «On the General Principles of the Organization of Local Government in the Russian Federation» (October 06, 2003 No. 131-FZ with further amendments up to 2016).

The main difference between the two versions of the law lies rather in the sphere of the legal language and casuistry. The law No. 131-FZ referred the following items to the «questions of local importance of the urban district»:

-

«… the establishment of the conditions for the transport services provision to the population within the city district», and also

-

«… the road activities in relation to the roads of local importance within the city district …».

It has to be clarified that the term «road activities in relation to the roads of local importance within the city district» makes just little sense, as the thesis on «construction, repair works and maintenance of the urban street and road network». How it is possible «to organize transport servicing of the population» without any preliminary conditions—this is the question for the Russian lawmakers.

Certainly, the problem is not only in formulations. The main thing is that a question of the funding sources, needed for implementation of these mandates, is mentioned in new law even more indistinct, than in the previous version:

-

The local budgets get subsidies in compliance with the Budget Code of the Russian Federation and the relevant legal acts of the federal subjects of the Russian Federation

-

The local budgets can obtain other interbudget transfers from the budget of the federal subject as provided by the budget code of the Russian Federation.

As may be seen there are no references of «the minimum state social standards» or promises to give the local government any «assignments from the federal taxes and taxes of the federal subjects of the Russian Federation». But it is quite clear, that the city can receive money from the federal or the regional budget only on the basis of co-financing.

In major cities all these legal regulations were reduced to a simple principle: if the city’s mayor accurately submits to the governor, or doesn’t have any conflict with the regional power, there will be some funds for the support of the Urban transport system in the regional budget, and vice versa.

One more key point in the relationship of the federal public authorities and the local government is connected with the adoption of the amendments to the Urban planning codeFootnote 13 of the Russian Federation in 2014.

According to these amendments, in the field of urban planning activities the federal authorities were obliged to «determine the requirements to the complex development programs of the transport infrastructure of settlements, city districts». In compliance with the adopted requirements (the resolution of the Government No. 1440, December 25, 2015), the local government were ordered, that the «Programs of complex development …» have to provide «the development of the transport infrastructure in relation to the needs of the population in transportation, as well as the entities provide the transportation of passengers and freights within the settlements and city districts». It is difficult to challenge such common truths. It is necessary to stress, that, first, just the same theses were in the Soviet documents in 1930–1940s, secondly, such requirements from the federal center mean the assignment of a new set of the non-financed mandates on the local government.

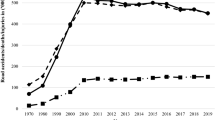

In general there are all reasons to consider that the efficiency of the urban transport policy corresponds to the composite governance indicators, estimated within the Global Competitiveness Index of the World Economic Forum (Table 6.2).

As we see, the indicator of the political institutes efficiency in Russia reaches below average value within last 8 years: the range is between 2.91 and 3.16. The efficiency of the budget spending also remains in the same values, but unfortunately, this indicator wasn’t measured in the first decade of the Noughties therefore it isn’t possible to compare the periods of centralization and decentralization of the public administration. In spite of the fact that the indicator of transparency of government policymaking improves every year (3.05 in 2007 and 3.97 in 2014), it reflects the development in the area of e-government and the free-access to information, but isn’t able fix the issues of the informal institutes activity.

6.5 Main Actors of Urban Transport Policy and Their Interests

In this part of the chapter, we will concentrate on the main (minus the city authorities) actors influencing or potentially capable to influence the development and the functioning of the city transport systems, and also to reveal the consequences of their activity.

The big business

The main actors in this segment are the building companies and the producers of the vehicles. They have a considerable potential to influence not only on transport policy, but also on town-planning one.

The building companies are interested in those regions and the cities where (on a fixed or temporary basis) there are sufficient financial opportunities to implement great projects on transport infrastructure. During the whole decade of the Noughties such potential was kept by Moscow where the large-scale transport construction was carried out generally at the expense of the city, which also enjoys the status of the federal subject. St. Petersburg was also attractive for the transport construction: along with the city budget, the financing was provided by the federal funds and funds of private investors within PPP. The list of the cities with the active transport infrastructure development includes also Sochi (due to hosting of the winter Olympic Games-2014), Kazan (in connection with the celebration of the 1000 anniversary of the city and hosting of the world Universiade-2015), Vladivostok (because of the hosting of the APEC summit), some other the cities.

The most interesting case for the analysis is the experience of Moscow and the Moscow Area, because in some years 60–70 % of investments in the transport construction objects were concentrated there.

In 2012–2015 in line with the «Development of Transport System of Moscow»Footnote 14 program the investments into the road and subway construction made about €2 billion annually for each direction, whereas the budget costs on the land public transport made about €200 million a year. At the same time in structure of population mobility of Moscow the public transport makes 80 %, whereas the private cars make only 20 %.

The comparison of these indicators shows: first, there is an inconsistency between the structure of the budget investments and the mobility structure, second, there is an obvious predominance of programs on the transport construction over other forms of the transport system support.

On this basis it is possible to claim that the companies (while being the leaders of the infrastructure construction segment) defend their interests in Moscow and dictate the priorities of the budget expenses.

Despite these circumstances, it should be noted that the S. Sobyanin’s administration managed to weaken the influence of a construction lobby. Although the structural issues on the distribution of budgetary funds still remain, it is possible to claim that the practice of the ineffective projects (initiated by companies close to the state authorities) in the city programs has become a thing of the past.

An illustration in point is the construction of a so-called Alabyano-Baltic tunnel. This deep and complex tunnel was built across Leningradsky Avenue below the level of the Zamoskvoretskaya subway line. It was about 10 years under construction and the project costs made about €1.3 billion.Footnote 15 The expedience of this construction was questionable in terms of traffic. As a matter of fact, there was a selection of a construction object which had to serve the interests of the certain contractor (the scientific-production association «KOSMOS») and was close to administration of then Moscow Mayor Yu. Luzhkov. This example is typical for the crony capitalism. The president of the contractor-company which failed to complete this tunnel was included in the Forbes list of billionaires and is wanted by Interpol. The construction was finished by the new contractor, which had sought for the new project decisions and additional budget costs in order to make the project more reasonable.

It is important to mention the companies producing the vehicles among the influential actors of the urban transport policy. Their interests are also concentrated generally in Moscow, St. Petersburg and other big cities where there are sufficient financial opportunities for the large-scale wholesale purchases of the passenger vehicles.

The standard example is presented by the tenders in 2014–2015 on the purchase of 1600 cars for the Moscow subway. Not only the Russian machine-building concerns (Uralvagonzavod (UVZ), Sinara and CAF Group) got interested in these tenders, but also such leading global manufacturers like Bombardier.

The winner of both tenders was “Transmashholding” concern. Among the shareholders are JSC “Russian railways” (25 %), “Alstom” (25 %) and business-structures controlled by I. Makhmudov and A. Bokarev. Tenders resulted in two contracts—supply of 832 rail cars in amount of 1.88 billion euros and 768 rail cars amounting to 1.72 billion euros.

The case itself clearly represents relations between Russian government and large business.

Conclusion of these deals raised a wave of public criticism—people thought that M. Liksutov, Moscow Vice-mayor responsible for transportation policy, had connections with the supplier.

On the other hand, these deals ensured the conclusion of the contract with 30-year life cycle, allowing the long-term stable supply of high-tech rolling stock. Conditions given allowed the ordering party to receive guarantee for maintenance of the rolling stock in stable technical condition by the manufacturer for the whole period of their operation.

At the same time, competing companies filed a complaint to the Russian antimonopoly agency, paying attention to the fact that the initial tender price was too low for them, and made participation unreasonable in economic sense. The nominal buyer—Moscow Metro and the real payer—the Moscow budget were at an advantage over the conditions of these contracts.

We can find some more specific examples of the rolling stock manufacturers participation in urban transport policy.

In the 1990s main active transport market players in Russian cities (except, of course, Moscow and St. Petersburg) were suppliers of used buses, trolleybuses and trams, not even the producers of new equipment. Old rolling stock decommissioned from the EU countries due to the exhaustion of the warranty mileage, or non-compliance to existing environmental standards has fulfilled the supply side. Local officials and transportation managers actively participated in conclusion of the supply contracts, which had “gray” character and often involved corrupt schemes. Brokers bought old vehicles from the cities where latter were decommissioned at give-away prices similar to the prices for scrap metal. The margin of the transaction appeared to be more than comfortable, even with the low prices at which Russian cities were willing to buy old rolling stock.

By any criteria—political, moral, environmental—these deals looked quite doubtful. However, the purchase of second hand equipment has allowed the peripheral cities of Russia to update the fleet of vehicles and, therefore, to maintain municipal carriers “afloat”.

Another case of 2014–2016 period is associated with the production of NGV buses. That is equal to for approximately 10 % of buses manufactured in Russia. The demand for this technique was not very active: peripheral Russian cities have very scarce resources for the renewal of municipal carriers’ fleet and are extremely reluctant to buy vehicles requiring additional infrastructure for maintenance and fueling.

NGV buses manufacturers get the lobbying support from Gasprom gas-engine fuelFootnote 16 and have succeeded in adopting the decision of the Russian Government (RF Government Decree (Postanovlenie Pravitel’stva RF) 2014), allowing “the provision of subsidies for bus purchase … working on gas motor fuel, under the subprogram “Automobile industry”” of Russian state program “Development of Industry and increase of its competitiveness”. After the lobbying demand from cities and regions to participate in the program significantly exceeded planned budgetary provision. It turned out that conditions for NGV buses purchase under federal program were more profitable for cities than buying buses built on conventional diesel technology.

Another illustrative case refers to trolleybus manufacturers, including leading Russian producer—JSC “TrolZa”.

Here it is necessary to make an excursus. In our opinion, the trolleybus—land transport that runs directly on the city streets and gets energy from the overhead wiring, has no future in sustainable urban passenger transport systems. The “sustainable mobility” ideology had provoked strong demand for high-quality rolling stock and, accordingly, an active supply of new technology by the world’s leading market players in the transport engineering field.

The main trends in this process are quite clearly defined nowadays. The first of them—rail cars, HRT and LRT. Second—all state-of-the-art buses: diesel buses of Euro-5 and Euro-6 environmental classes; vehicles with an engine running CNG (compressed natural gas) or LNG (liquefied natural gas), various type “hybrids” (gas-diesel, diesel-electric, gas-electric). Finally, the electric buses with longer capacity of autonomous run. In all segments fierce market competition involves many of the leading market players—manufacturers of cars and rolling stock. This leads to radical technological superiority of the vechicles produced over old exemplars in terms of energy efficiency, comfort, speed, ease of entry/exit, operational reliability, design advantages, and, of course, adaptability to the needs of people with restricted mobility.

Unfortunately, this process affected the trolleybus sector in a very small extent: today about 70 % of the trolley buses world fleet is still concentrated in the ex-USSR cities. As far as we can judge from the outside, urban managers and transport planners in developed countries, do not consider this transport mode to be competitive and promising.

For example, in Belgium, homeland of Alain Flausch, the current UITP (International Association of PublicTransport) Secretary General, authorities have turn down trolleybus systems. The same trend one can observe in France, Pierre Laconte motherland, previous longstanding UITP Secretary General. Trolleybuses have disappeared or almost disappeared in all other developed countries, which are major “fashionable” trend-setters in public transport over the last fifty years: Austria, Germany, Netherlands and Japan.

A number of reputable experts, one way or another involved in the UITP Trolleybus Committee activities, retain the belief in a short renaissance of this urban transport type. They appeal to the highest environmental, technical and economic advantages of the trolleys, as well as to new opportunities associated with an increase of autonomous run distance. With all due respect to colleagues, we cannot share their optimism: progress in the trolleybus segment, alas, never keep up with innovations in car and bus segments, backed by massive investment and engineering potential of leading market players. For example, mass production of electric buses that are able to compete with conventional diesel buses at the life cycle price and the ease of use—is a question of next few years. Obviously, the appearance of such electric buses will have finally close the chapter on prospects of the traditional trolleybus tied to the overhead contact wires.