Abstract

The centrality of the faculty role makes it a primary sculptor of higher education institutions (HEIs). The performance of academic staff such as teachers and researchers has an impact on student learning and implications for the quality HEIs and therefore their contribution to society. Thus the academic staff can, with appropriate support, build a national and international reputation for themselves and for the institution in the professional areas, in research and in publishing.

The Portuguese higher education system has been faced with major reforms over the last years, which include the implementation of the Bologna Process, the approval of a new legal regime for the HEIs and the approval of new statutes relating to the academic career in the public HEIs.

Job satisfaction and motivation are viewed as a predictor of positive attitudes at work, productivity, and, consequently, good results for the institutions. The purpose of this chapter is to present and analyse the findings of a nationwide study on satisfaction and motivation of academics in Portuguese public higher education institutions. The data are extensively analysed and findings are presented here, along with the implications they offer to Portuguese public HEIs.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

The work of academics is influenced by global trends such as accountability, massification, deteriorating financial support, scientific progress and managerial controls (Altbach and Chait 2001; Galaz-Pontes et al. 2007; Henkel 2010). Authors such as Kogan and Teichler (2007, p. 9) stressed “[…] the academic profession has come under enormous pressure potentially endangering the survival of the core identity of academics and universities… Increased expectations and work roles from society and notably the perception of knowledge as the most vital resource of contemporary societies have both expanded the role of the academy and challenged the coherence and viability of the traditional academic role”. Changes in the academic career are emphasized by Henkel (2007, p. 201) “Most academics now work in a multi-functional organizations, in which the definitions of work and responsibilities have expanded and become more varied, for them and for others, and organizational principles have been incorporated.” Also Gappa (2010, p. 209) argues “The effects of changes in faculty work, appointments, and demographics in their colleges and universities are being felt by faculty members, who are experiencing declining autonomy in their work, escalating workloads, an increasingly diverse student body, and, for some, a change in the nature of the academic community.” Many authors will describe other trends including for instance

-

“[…] as a threat to academic autonomy as one of the central tenets of university life” (Brennan 2007, p. 20);

-

“Traditions of academic freedom, professional autonomy, and allegiance to disciplinary fields continue to characterize what means to work in higher education. An extensive literature points to the survival of these values as being critical to the future of academic work” (Gordon and Whitchurch 2010, p. XVII);

-

“Academic faculty find themselves working with and to a broader range of stakeholders and in more national and international sites than before […]” (Marginson 2009, p. 105);

-

“[…] on-going evolution of the academic profession: the transformation of academic activities” (Musselin 2007, p. 185);

-

“[…] increasing influence of institutional leaders (be they ‘academic’ or not) in decision-making processes that affect the individual careers of faculty members” (Musselin 2010, p. 125);

-

“democratization of knowledge in “knowledge societies”” (Henkel 2007, p. 191);

-

“[…] the authority of academic knowledge is no longer taken for granted” (Henkel 2010, p. 11);

-

“From the standpoint of the Academic Estate, the significance of new specialized and technical functions on the margins of academia is central. It engages the crucial issue of how boundaries of Academia may be defined in the future.” (Neave 2009, p. 12);

-

“But the majority of academics believe that higher education these days is being exposed to excessive instrumentalist pressures.” (Teichler 2009, p. 65).

Hence, we assisted to the rapid change of the academic workplace and the necessity to manage the tensions within the academic profession. On this note, Altbach (2003) argued that with the era of mass higher education the conditions of academic work have deteriorated everywhere. Moreover Kogan and Teichler (2007, p. 11) argue “One view would see a victory of managerial values over professional ones with academics losing control over both the overall goals of their work practices and their technical tasks”.

Thus, HEIs have to manage their resources and human resources in particular in order to be proactively positioned to seize opportunities and confront threats in an increasingly competitive environment. Therefore more and more importance is placed on the satisfaction of the constituent groups of HEIs, namely the academic staff, among others (Machado et al. 2011).

The importance of work for us and for our satisfaction is evident. “Work plays a prominent role in our lives. It occupies more time than any other single activity and it provides the economic basis for our lifestyle. Therefore, job satisfaction is a key research area for numerous specialists and is a heavily researched area in the recent years” (Santhapparaj and Alam 2005, p. 72).

According to Silva (1998), being in the market today is being in a permanent evaluation of competitive ability. It becomes clear in this context the importance of the human factor and its “involvement” in the objectives of the organization.

The centrality of the faculty role makes it a primary sculptor of the institutional culture. The performance of academic staff as teachers and researchers determines much of the quality of the student satisfaction and its impact on student learning and thus the contribution of the HEIs to society (Ambrose et al. 2005; Capelleras 2005; Gappa et al. 2007; Hagedorn 2000; Höhle and Teichler 2011). Therefore the contribution of academic staff within an HEI has implications for the quality of the institution (Altbach 2003; Enders 1999; Teichler 2009). However, HEIs are extremely complex social organizations. One must examine a multitude of factors and their numerous interactions even to approach an understanding of its functions. HEIs are now in a time of globalization, traversed by profound contradictions, uncertainties and doubts. Those concerns are due not only to a lack of resources or quality of resources, but also are conceptual in nature and concern with the extension and amendment of the HEI mission with reflections on the academia (Burbules and Torres 2004; Morgado and Ferreira 2006), with consequences also for the job of professors (Hargreaves 1998, 2003; Tardif and Lassardi 2008).

Serious research reveals that the concept of job satisfaction is a complex collection of variables that interact in a myriad of ways. Furthermore, the precise arrangement of these factors differs across segments of the job market. There are intrinsic variables related to personal growth and development, and extrinsic factors associated with security in the work environment. There are global trends that impact professors and universities – notably accountability, massification, managerial controls, and deteriorating financial support (Addio et al. 2007; Hagedorn 2000; Stevens 2005). There is also ample and somewhat obvious evidence that job satisfaction relates to employee motivation. Job satisfaction is important in revitalizing staff motivation and in keeping their enthusiasm alive. Well motivated academic staff can, with appropriate support, build a national and international reputation for themselves and the institution (Capelleras 2005) in the professional areas, in research and in publishing. Such a profile may have an impact on the quality of HEI. In this context, institutions and their leaders who understand the intricate tapestry of organizational culture have an opportunity to tap the multiple resources at their disposal and thus manage job satisfaction and employee motivation more effectively (Machado et al. 2011).

Over the recent years, there have been many changes in Portuguese higher education. These include, among others: the implementation of the Bologna Process, which was given particular visibility; the approval of a new legal regime for the HEIs, which paved the way for the existence of the foundational regime and the approval of new statutes relating to the academic career in the public HEIs. Thus, the changes affect and will continue to affect academic careers (Machado-Taylor et al. 2010).

One important point to note about previous studies of satisfaction is reported by Changing Academic Profession (CAP) project. According to this study, Portugal is among the countries with lower levels of overall satisfaction. For instance, only South Africa showed a lower level of overall satisfaction among academics (International Database of the CAP Project (Dias et al. 2013). Also, the EUROAC survey reports that Portuguese junior academics are among the less satisfied (Höhle and Teichler 2011).

This chapter will provide a diverse range of information on multiple dimensions of the faculty job satisfaction in public Portuguese higher education institutions. The findings of a nationwide study on satisfaction and motivation are extensively analyzed.

2 The Academic Career in Portugal: Issues and Challenges

In this section we present and analyse the structure of the academic career in Portugal. We start by describing the evolution of the career since 1970, highlighting the changes that took place with the stabilisation of the democratic life after the revolutionary period and other changes that occurred as an adaptation to the recent evolution in European Higher Education including the application of the Bologna Process in Portugal.

First we briefly describe the evolution of the organisation of the Portuguese Higher Education (HE) system since 1970 until 2012. In particular we underline the reforms experienced in 1973, the introduction of the Polytechnic subsystem in the late 70s, the expansion of the HE system, including a brief analysis of the emergence of the private sector.

In the second section the evolution of the academic career is presented and a detailed description of the present legislation regulating is also included.

2.1 Evolution and Organization of the Portuguese Higher Education

The higher education system in Portugal is a binary system, including universities and polytechnics, initially planned in the early’1970s. It was mainly from the second half of the 1970 that the growth and the dissemination of higher education started, after the democratic revolution in 1974. Until the early 1970s the Portuguese HE system was an elite system, it was attended by a small number of members of society, mostly from upper classes. There was a situation of great inequality based on the socio-economic origin (Cabrito 2006). Thus, the HE system was not a democratic one and this fact was the consequence of the very political system itself. After 1974, as a consequence of the democratization of the country the social demand for HE increased very much (Cabrito 2006).

Since then, many changes in higher education took place, namely: the implementation of the binary system; the distribution of higher education institutions (HEI) across the country; the approval of the statutes of the university academic career, in 1979, and of polytechnic academic career, in 1981; the approval of the Education System Act in 1986 (Law 46/86 of October 14); the approval of the laws of autonomy of the universities and polytechnics (Law n° 108/88 of September 24 and Law n° 54/90 of September 5, respectively); the emergence of the private sector in the 80s; and the massification of higher education. More recently, in the last decade, there were also other major changes in higher education. Among them it should be noted the amendment of the Education System Act, by the Law n° 49/2005, of August 30, in order to implement the Bologna Process, which was also followed by other important changes, including the approval of a new legal regime of the HEI (Law n° 62/2007 of September 10), the approval of the legal assessment of higher education (Law 38/2007) and the approval of amendments to the statutes of the academic careers in higher education in 2009 (Decree-Law n° 205/2009 and Decree-Law n° 207/2009, amended, respectively, by the Law n° 8/2010 and Law n° 7/2010, both of May 13).

Until the early’1970s, higher education was an elitist system, enrolling only a small number of students. There were only four universities, one in Coimbra, and one in Porto and two in Lisbon. In the early’1970s, there were important changes in the educational system, particularly in higher education. In 1971 the Catholic University was established. In 1973, a legal framework was approved (Law n° 5/73, of July 25), defining the basis of the educational reform. According to this law, higher education was provided by Universities, Polytechnics, Higher Normal Schools and other similar establishments (Base XIII, n°. 3). In the same year, by the Decree-Law n° 402/73 of August 11, the network of higher education was approved, creating new Universities, Polytechnics and Higher Normal Schools.

The aim was to modernize, expand and diversify the higher education, “so as to reach a rate of 9 % for the age group 18–24 years” (target set out in the preamble of the Decree-Law n° 402/73). As stated by Amaral et al. (2006, p. 41), the question was the necessity of “bringing the country closer to European standards, coupled with the influence of international organizations like the OECD, the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, which led that the government policies reflect an increasing number of ‘functionalization’ of education in general and in particular, higher education in relation to aspects of the country economic development”. The plan was ambitious, compared to what previously had been the policy of higher education. The implementation of this plan was interrupted with the establishment of democracy in 1974 and the days of the revolution that followed, and that changed the political agenda, including higher education (Magalhães and Santiago 2012).

In the late’1970s, the agenda of higher education was the subject of particular attention, in particular in what regards the diversification and the creation of polytechnic institutions. In 1977 the “short-term higher education” was introduced (Decree-Law n° 427-B/77), and was formally replaced by “polytechnic higher education”, in 1979 (Decree-Law n° 513-T/79). The professional scope of polytechnic education was emphasized against the “more conceptual and theoretical characteristics” of university education. The Word Bank played an important role in the development of polytechnic subsystem, being responsible for several projects carried out until the integration in EU.

In the early’1980s, there were public higher education institutions in all districts. At the end of the 1970s, the Law on Private and Cooperative Higher Education was approved (Law 271/79), although its implementation has occurred, particularly in the second half of the 1980s and 1990s (Teixeira 2012). In 1986, the year Portugal joined the EEC, the Education Act (Law 46/86 of October 14) was approved, consolidating the binary system. According to this law, universities could confer all degrees (“bacharel”, “licenciado”, mestre e “doutor”Footnote 1), while polytechnics could confer only a bachelor’s degree. This situation changed in 1997 (first amendment of Education Act – Law n° 115/97, of September 19) and from this date, polytechnics grant also the degree of “licenciado”. In 2005, the Education Act was amended in order to implementing the Bologna Process (Law 49/2005, of August 30). The law maintained the binary system. The number of higher education degrees was changed from four (“bacharel”, “licenciado”, “mestre” e “doutor”) to three (“licenciado”, “mestre” e “doutor”). Actually, universities grant all degrees while polytechnics grant the degrees of bachelor and master. The amendment of 2005 was followed by other changes, including the adoption of a new legal regime of the HEI (Law n°. No. 62/2007 of September 10) and the approval of legislation regulating accreditation and evaluation of higher education institutions and study programmes (Law n° 38/2007 of August 16).

Only after democratization in 1974, a significant expansion of higher education was initiated. In 1978 the total number of students enrolled in higher education was 81,582 (77,501 in the public sector and 4081 in the private sector). In the following years this number has been increasing, reaching in 1990 the total number of 157,869 (119,733 in the public sector and 38,136 in the private sector). At this time, higher education was already present in many cities and counties, although some of HEI have small size. In the following years, this number has continued to grow and in 2003 it reached 400,831. However this growth was different by subsystem and type of education.

In the private sector, the number of students reached the highest number in 1997, reaching 121,399 (96,163 in the universities and 25,236 in the polytechnics). Since then it has been declining, reaching 78,699 in 2012 (55,147 in the universities and 23,552 in the polytechnics). Private universities reached the maximum number of students in 1997. Since then it has been continuously decreasing. The private polytechnic subsystem reached the highest number in 2003 and since then it has also been decreasing.

In the public sector, the trend has been different. The number of students reached the highest number in 2012, total of 311,574 (197,912 in the universities and 113,662 in the polytechnics). The public university subsector has always grown, except for the period 2004 to 2009. The public polytechnic subsector reached the highest number in 2011.

From 1997 to 2012 the private sector has lost 42,700 students, mostly in the university subsector. In the same period, the public sector has grown 98,848 (50,563 in universities and 48, 285 in the polytechnics) (Table 5.1).

The establishment of the binary system in the late 70s and its development in the following decades, aimed at the existence of two sub-systems with different goals and philosophies. The main idea was to expand higher education in the country and regional development, locating the polytechnics and their schools especially in cities where there were no universities. Its education programmes would be of short duration or up to 3 years of an applied nature and would be designed to meet the needs of work in the regions where they were deployed. There had been planned research activities for the polytechnic system. The research activities were taking place in universities and it was also these institutions that formed the faculty of polytechnics. In this sense, it can be said that the training of teachers of polytechnics was dependent on the universities. This situation has been changing and went to a growing rapprochement between the two subsystems, namely in terms of research. In fact, there are today research units in polytechnics.

The current system of higher education includes: 14 public universities, the Catholic University and a non-integrated public University Institute (institutions awarding university degrees, but not having the necessary conditions to be universities), all represented in the Portuguese Rectors’ Conference (CRUP); 15 public polytechnics, represented in the Council of Portuguese Polytechnics (CCISP), and five schools not integrated in polytechnics (polytechnic institutions awarding degrees, but not having the necessary conditions to be polytechnics); and six public schools of higher education, depending on both the Ministry of Science and Education and other Ministry (Military Schools and Police Academy). Higher education includes also 99 private institutions, including 39 university institutions (universities and non-integrated institutes or schools) and 60 polytechnic institutions (polytechnics institutes and non-integrated polytechnics schools) (http://www.dges.mctes.pt/DGES/pt/Estudantes/Rede/Ensino+Superior/).

2.2 The Academic Career

The higher education system in Portugal, being a binary system, is characterised by the existence of different academic careers. The legal framework of academic careers is quite different in public and private institutions. The government defines the size of the teaching staff and creates the rules for career advancement within public institutions. The academics of public institutions are civil servants, as opposed to those that work in private institutions (Meira Soares 2001, 2003; Meira Soares and Trindade 2004).

The main regulatory frameworks of academic careers date back to 1970 (Decree-Law n° 132/70, March 30), 1979/80 (Decree-Law n° 448/79, November 13, and Law 19/80, July 16) and 1981 (Decree-Law n° 185/81, July 1). Recently, in 2009, the statutes of academic careers were subject to changes, after they have been in force for three decades. In the following pages, we cover the main changes in the academic career from the’1970s to the present day.

2.2.1 Shaping the Academic Career in the Early 1970

Until 1970, matters relating to university academic career appeared associated or integrated in the Statute of University Education. In 1970, the academic career was treated in a specific regulation (Decree-Law 132/70, dated March 30). There was not binary system of higher education in Portugal. According to this normative the academic career focused on two major areas, teaching and research, although they also set out some administrative functions. In the introduction of this normative some issues were reported regarding higher education, namely the difficulties of recruiting qualified academics to cope with the increase of school population, salary and career conditions offered. Furthermore, the need to create conditions for achieving the doctoral degree was also raised, because the system was facing a lack of professors and unattractive conditions for the academic career.

The university career was divided into two phases: “the first one, especially devoted to the preparation for teaching and learning methods of research and the second one devoted to the full exercise and training of researchers.” The first phase included the assistants and the second one the professors. Thus, the academic career was structured into two main groups: professors (full professor, extraordinary professor and auxiliary professor) and teaching assistants (readers, assistants, junior assistants and monitors). It was the structure shaping the academic career over four decades, until the changes introduced in 2009.

In the normative, more emphasis was given to teaching and research and after to the administrative tasks. Referring to this period, Caraça et al. (1996) say that the dominant model of the university up to 1970s gave priority to education and that only in the 80’s emphasis to the research university was given, a trend reinforced in the following decades with the development of postgraduate programmes and the evolution of the university towards a greater openness to the outside society and the productive system.

2.2.2 The Diversification of Academic Careers in Higher Education

The expansion and diversification of higher education was the subject of particular attention from the late 70s and was followed by the approval of the university academic career legislation in 1979 (Decree-Law n° 448/79 and Law 19/80) and the polytechnic academic career legislation in 1981 (Decree-Law n° 185/81). Analysing this legislation we are faced with two different realities.

In the case of university, the structure of academic career designed in 1970 continued. The introductory of the new legislation was focused on a diverse set of issues, namely: a lack of qualified academic staff, the need to “make the career more attractive and dignified”; the need to provide means for assistants to obtain the doctoral degree; improving the quality of universities for international competition; the creation of conditions for graduates professionals to “neutralise or mitigate the effects of centrifugal […] requests from the private sector and even the public sector”; the idea that the university is not a “simple factory graduate” but “a comprehensive institution, dedicated to undergraduate and graduate teaching, to fundamental and applied research and to providing highly specialised services of undeniable social interest”; the full realization of the academics and of the universities, the creation of conditions to decrease bureaucracy and more autonomy; a more professional career with more employment stability.

In the case of polytechnic the main aim was to approve the creation of a new career, for the recently created subsystem (Decree-Law no. 185/81). In that sense, the creation of a new academic career was considered fundamental to the development of polytechnic education. On the introductory part of the decree-law, it was reported that this career was in line with “the teaching of higher level, targeted to the technicality and specificity of the various professional activities, claimed by modern societies”. It was the desired connection between polytechnics, professional activities and regional development, which was emphasised in legal texts regarding polytechnics, namely the Decree-Law n° 427-B/77, the Decree-Law n° 513-T and Decree-Law n° 513-L1/79.

There were two different agendas for academic careers. In the case of the university the academic career was faced with the need for universities to modernise and respond to new demands and challenges, coming from both inside and outside the country, including increasing massification, which would deeply influence the end of the century and the beginning of the next. In the case of polytechnics, the purpose was to diversify higher education, developing a different subsystem and disseminating it over the country and, at the same time, creating a different academic career. This diversity of careers continued until the recent changes in 2009.

The university career (Decree-Law n° 448/79) had the following sequence: Assistente Estagiário (junior assistant), Assistente (assistant), Professor Auxiliar(auxiliary professor), Professor Associado(associated professor) and Professor Catedrático(full professor). Access to the lower rankinvolved the undergraduate degree, starting in the position of Assistente Estagiário, which remained for 2 years. After this period, the person was promoted to Assistente, which involved the acquisition of the master’s degree. His/her career continued as Assistente for 6 years, during which he/she should acquire a doctoral degree to be promoted to the next category: Professor Auxiliar. This new situation did not guarantee, by itself, a permanent academic career. Indeed, after 5 years of service in this category, an applicant had to submit a very detailed “curriculum vitae” to the Scientific Council of the Institution, which, upon evaluation of academic performance, decided in favour (or not) of changing a temporary contract to final contract. Access to the next category, Professor Associado, required submission to a public competition, and implied a minimum period of service in the category of Professor Auxiliar, the condition for permanent appointment in this category not being required. In practice, access to a permanent appointment in the university academic career meant 13 years of service. Access to the rank of Professor Catedrático, the highest cumulative depended on three conditions: to be Professor Associado, the title of Agregado (may be compared with German notion of Habilitation) and submit to a public competition.

A career in polytechnic (Decree-Law no. 185/81, 1 July) included fewer categories: − Assistente (1st and 2nd triennium), Professor Adjunto and Professor Coordenador. Access to the rank of Assistente required a suitable higher education qualification (bachelor’s or graduate). To progress to the next category, Professor Adjunto, it was necessary to obtain the master degree and to be a candidate in a public competition. Access to this category did not imply, by itself, a permanent appointment. This occurred only after a period of provisional appointment of 3 years, after which the candidate had to submit a detailed report to the Scientific Council and only with the approval of this body the appointment became final. Access to this category could also be done through public examination in the case of candidates without a master’s degree. In practice, access to a permanent appointment in the polytechnic academic career meant 9 years of service. To access to the next category, Professor Coordenador, the Professores Adjuntosshould be candidates in a public competition.

2.2.3 The Academic Career in the 2000s

The legislation concerning academic careers in public institutions of higher education has remained unchanged, or nearly so, over the last three decade, despite repairs and criticism over the years (Meira Soares and Trindade 2004). Changes arrived in 2009 by the approval of amendments to the statutes of academic careers in higher education, both public universities and polytechnics (Decree-Law n° 205/2009, n° 206/2009 and n° 207/2009, amended by the Law n° 7/2010 and n° 8/2010), after the amendment of Education Act in 2005 (Law 49/2005), in order to implement the Bologna Process. These changes in the statutes in 2009, occur in a national context characterised by a binary system already implemented and disseminated throughout the country and after other major changes for Portuguese higher education were approved, including the adoption of the new legal regime of the HEI governing regulations (Law 62/2007) and of the new HEI’s evaluation system (Law 38/2007).

In 2009, a new legal framework changed the academic careers regulations. Under this new regulations, the academic careers in public HEI’s were changed, although the main structures remain very similar. According to the new legal framework, academics of university and polytechnic public institutions continue to have different careers. Nevertheless, with the recent changes, there has been an approximation between the two sectors. Unlike what was published in 1979 and 1981, the preambles of the statutes in 2009 are very similar, sharing largely the same text, a sign that the issues of higher education are now largely common to both subsystems. The difference between them does not appear as 30 years before. Confining ourselves to the question of academic careers, the preambles of the diplomas focus largely on a common agenda. They are focused on issues such as: the modernization and strengthening of the vital contribution of higher education for the development of the country; the new challenges that higher education is called to respond to today; changes in the legal framework of employment of academics; changes in the careers of both subsystems, namely in the rules of the access to the academic career and of the public competitions to fill vacant positions; autonomy of HEI to produce regulations regarding the management, recruitment and assessment of performance of academic staff. The jury judging the filling a post through a public competition (always international for the filling of university positions) must have a composition with a majority of external members. With these new legislations in-breeding becomes more difficult, internationalisation is favoured and mobility is encouraged.

As noted above, the academic careers remained unchanged over the past three decades. Amendments in 2009 refer mainly to the career structure, the access and mobility, the recruitment and the academic work. In The following table (Table 5.2) shows the professional categories of both subsystems, before and after the amendments made in 2009, with reference to legislation on the public sector.

In university career, a doctoral degree was required to access to the categories of professor. In the case of polytechnic education, the degree required for access to the categories of professor was a master’s degree, but you could access these categories, without a master’s degree, through the provision of public exams. With the changes of 2009, the degree required to access the categories of professors in both subsystems, is the doctoral degree. However, in the case of polytechnic education the title of specialist was also created, and can be obtained through public examination in which it is necessary to prove “the quality and the particular importance of the professional curriculum in a particular area for the performing functions of the polytechnic teachers” (Decree-Law n° 206/2009). Moreover, these experts, provided they meet certain requirements, may also apply to “professor coordenador”, but not to the Professor Coordenador Principal. Access to this category, created in 2009, implies that in addition to other conditions candidates must be holders of the Agregado. The other categories provided for in previous legislation, no longer exist or remain in a transitory existence, according to new legislation. In addition, there remains the possibility of hiring teachers in HEIs situation of guests.

2.2.4 Academics’ Functions

The approval of the statutes of the academic careers of 2009 brought closer the two careers also in respect to general functions of academics. One remaining difference between the two careers is the weekly teaching load, which is higher in polytechnics (9–12 h) than in universities (6–9 h). With regard to functions, in general, for academic staff in both subsystems in public higher education, they show small differences (Table 5.3). The main differences appeared in the regulations adopted by each HEI concerning the provision of teaching since this matter became the responsibility of each HEI.

The changes in 2009, increases the quantity and diversity of tasks required to academics, and can be systematised into five groups of activities: (a) Research and development (scientific research, cultural creation, technological and experimental development); (b) Teaching (teaching service, monitoring and mentoring of students); (c) Participation in activities related to the scientific and technological dissemination and economic and social value of knowledge; (d) Participation in the management of institutions; (e) Participation in other duties assigned by the competent bodies, in the institution.

The first two groups are activities with a tradition in the academy. The following two formulations did not appear so explicitly in the previous statutes. The final group adds new responsibilities, whose definition is at the discretion of each HEI. From the classic teaching and research, the function and tasks of academics are moving to “other activities”, which also means some ambiguity. Only the regulations of the HEI, in particular regarding with the provision service and performance evaluation, are likely to clarify the meaning of “other activities”

2.3 Coping with the Changes

In a few decades, Portugal changed from a system of higher education of elites to a system of mass higher education, showing signs of stabilization in the last decade. With the expansion of higher education, there was also an increase in the number of academics, rising from 2726 in 1971 to 9097 in 1981, an increase that occurred mainly in the public sector. In the following decades, from 1981 to 1991 and from 1991 to 2001, growth continued to be very high. Since 2001 we are seeing some stabilization (Table 5.4).

In the 2000s, there was an improvement in the academic qualifications. The number of PhDs increased from 9465 in 2001 to 16,771 in 2010 and the total number of non-PhD decrease in the same period from 26,275 to 21,393 (GPEARI/MCTES). Another fact to be noted is the increasing feminisation in higher education. In the period from 2001 to 2010, the number of female teachers increased from 14,571 to 16,650. In the same period, there was a decline in male teachers, whose numbers rose from 21,169 in 2001 to 20,459 in 2009. The percentage of female teachers is higher in the polytechnic than in university education. In 2010, the percentage was 43.7 % in polytechnics and 40.2 % in universities. Throughout the first decade of this century there was certain stability in the number of academics. But in terms of age, there is some aging. Indeed, from 2001 to 2010, the number of teachers in the age-groups <30 years and 30–39 years decreased and the number of teachers in all other groups increased.

2.4 Challenges

There are various challenges academics and HEIs are currently facing, namely: the evaluation and accreditation, the developments of the Bologna process and the implementation of the European Area of Higher Education, the future development and reorganization of higher education network and its relation with the decreasing number of students and the economic anxieties.

Issues of evaluation and accreditation in higher education are some of the main concerns of both politicians and academics. One of the recent changes was the adoption of a new system of evaluation and accreditation of HEI (Law n° 38/2007, August 16), which led to the creation of A3ES.Footnote 2 The accreditation and evaluation of programmes of study, now under A3ES, is taking its first steps. The creation of programmes is now dependent on prior accreditation by A3ES. In addition, programmes are subject to periodic review, consisting of a set of guidelines that HEI’s should take into account when implementing their programmes and self-assessment processes.

Study programmes are evaluated every 5 years and the process is based on a self-assessment (where students’ opinions are included), followed by an external evaluation carried out by academic peers (domestic, external and foreign experts). In the previous evaluation system, there was not a link between direct and immediate results of evaluations and recognition of study programmes or other any consequences.Footnote 3 Actually, the process of accreditation has immediate consequences, namely non-accreditation. The implementation of the process of evaluation and accreditation is one of the main challenges that HEI and academics are faced with. Not accredited study programmes no longer work, which has consequences for the HEI. At the same time, this process also has an impact on academic work and may lead to termination of employment contracts of academics. These policies have important effects on the working conditions of academic staff and are related with quality assurance of HEI.

Another important challenge for higher education institutions and academics is the creation of the European Higher Education Area, created by the Bologna Declaration. The amendment to the Education Act in 2005 (Act 45/2005), has provided the implementation of the Bologna Process in Portugal. However, it has been a process that has not always received the consensus of the academic community. Actually, the system of degrees and diplomas in HE is organised according to the Bologna Process. However, in certain cases, the previous degree programmes have been replaced by new ones, merging undergraduate and master’s degree (integrated masters), as is the case in various engineering, pharmacy, medicine. Identical procedures were not adopted in all areas of education and training. The introduction of the ECTS credit system happened but it needs yet some developments, particularly in terms of curriculum and teaching methods. On the other hand the concept of learning outcomes is not yet well known by the academics. It is also not clear to many students, academics and institutions that the acceptance of the principles of Bologna force them to change their attitudes regarding teaching and learning. It is difficult to predict the effect of these developments in the academic career. We believe that these changes are being reflected in the academic work. However, it is still early to say whether these effects are positive or negative for the academic career. The decrease in the number of training hours also resulted in a decrease in the number of teachers and in budget of HEIs.

As was already mentioned, in a few decades, Portugal passed from a higher education system of elites to a system of mass higher education. In the last decade, it is showing signs of stabilization and even some decrease in the number of students, which has led to increased competition between HEIs in attracting students. In this sense, the reorganization of the HE network is unavoidable. This reorganization may be the result of different options, including administrative (governmental) intervention, negotiation processes between institutions, market logics and so on.

HEI’s have been confronted with the decreasing number of students each year, a decrease that is not evenly distributed among different scientific disciplines. As a result, in some areas, there will be excess of teachers while in other areas, there may be a need to increase their number, although not many. As mentioned above, the number of teachers in the first decade of the 2000s showed signs of some stability. Simultaneously, there has been an increase in the level of their qualifications, given the high number who acquired a PhD degree. This is beneficial to the quality of human resources and also has the effect of increasing competition among academics seeking a job or a position in an academic career. Moreover, as noted above, during the first decade 2000s there has been some aging on the academic staff. Furthermore, the laws of work and social security have also been altered, so that reforms are of lower value and occur later than previously. This also makes it more difficult the rejuvenation on the academic staff. Moreover, labour laws making employments more precarious and dismissal easier.

All these “ingredients” associated with budget constraints increase pressure on public institutions. The autonomy of institutions is greatly reduced. It is still unclear how they will deal with these situations and what will be the effect in academic career. Some people argue, rightly, that there are study programmes in the country offered by institutions geographically very close to each other, making cooperation between them desirable in order to reduce costs. This argument is correct, and solutions can be implemented in this direction. However, the implementation of those solutions may be insufficient, given the fact that teachers are already in institutions and the savings will not be felt in the short or medium term, except in what concerns administrative costs. Moreover, HE is still distant from goals of 2020.

The problems of the private institutions are not minor. It is a fact that they invested mainly in study programmes that are less expensive, such as law, management, information technology, teacher training and alike. Some of these programmes are still the most preferred by the candidates to HE. The demographic recession is, however, bringing problems. Moreover, the taxes in private education are much higher than those of public institutions. Therefore, it is expected that financial problems will profoundly affect these institutions. Probably the merging processes will continue and some institutions will have to close, bringing additional problems to the academic community of these institutions. As a result unemployment among academics is indeed a threat the country faces, both at the university and at the polytechnic subsystems.

These data, as well as those mentioned above, show that there are many factors that influence the work of academics. Moreover, they also show that these factors are not unrelated to the times of change, uncertainty and instability on academic work.

3 Models for Examination of Academic Job Satisfaction

3.1 Some Models of Faculty Satisfaction

The literature on job satisfaction of academics is limited. However, authors such as Santhapparaj and Alam (2005, p. 72) stressed that “Work plays a prominent role in our lives. It occupies more time than any other single activity and it provides the economic basis for our lifestyle. Therefore, job satisfaction is a key research area for numerous specialists and is a heavily researched area in the recent years”. In fact, the “concept of job satisfaction is an important one for study because every individual has a variety of needs and values and much of a person’s activity in a workplace is directed towards the acquisition of means and ways to fulfil these needs and values” (Egbule 2003, p. 158). In this context, Gappa et al. (2007, cited in Gappa 2010) argued that faculty members value equity, collegial relationships (with colleagues and administrators), security in employment, professional development, autonomy, access to the resources they need to do good work, support from department chairs and institutional administrators and recognition for their work. These are factors that, according to these authors, lead to high levels of satisfaction.

Job satisfaction is multi-dimensional, with both intrinsic and extrinsic qualities. The former include ability, achievement, advancement, compensation, co-workers, creativity, independence, moral values, social service, social status and working conditions. The latter involves authority, policies and practices, recognition, responsibility, security and variety (Weiss et al. 1967).

For instance, Herzberg et al. (1959) distinguish Motivators or Intrinsic Factors – Achievement, Recognition, The work itself, Responsibility, Advancement, Growth; and Hygiene Factors or Extrinsic Factors – Company Policy, Supervision, Relationship with Boss, Work Conditions, Salary, Relationship with Peers. According to Herzberg et al. (1959) intrinsic factors relate to job satisfaction when present but not to dissatisfaction when absent. The extrinsic factors are associated with job dissatisfaction when absent, but not with satisfaction when present. Motivating job characteristics are associated with job satisfaction, intrinsic motivation and work effectiveness (Winter and Sarros 2002).

Nyquist et al. (2000), presenting their model for faculty job satisfaction, suggested that organizational factors, job-related factors and personal factors affect self-knowledge, social knowledge and satisfaction. Organizational factors are available resources, collegial relations among colleagues, perceived opportunity for promotion and advancement, adequacy of mentoring, decision-making abilities and commitment to the organization. Job-related factors integrate autonomy and academic freedom, clear and consistent job duties, job security, stimulation from work, workload, income, resources available and work-related time pressures. Personal factors include -perceptions of role conflict and interference of work responsibilities with home. The model shows that institutional context and individual characteristics influence faculty satisfaction (please see Fig. 5.1).

Conceptual model 1 of academic staff job satisfaction (Adapted from: Nyquist et al. (2000)

An adaptation of Hagedorn (2000) illustrates another model. L. Hagedorn (2000) wrote about faculty job satisfaction using the “Conceptual Framework of Faculty Job Satisfaction”, being her mission to sort and categorize the factors that contribute to job satisfaction. This model hypothesizes two types of constructs that interact and affect job satisfaction. These constructs are triggers and mediators. A trigger is a significant life event that may be either related or unrelated to the job. A mediator is a variable or situation that influences or moderates the relationships between other variables or situations producing an interaction effect. The mediators represent situations, developments and extenuating circumstances that provide the context in which job satisfaction must be considered. The conceptual model presented by L. Hagedorn (2000) is composed by six triggers and three types of mediators, forming a framework in which faculty job satisfaction may be scrutinized (please see Table 5.5).

To measure the job satisfaction of university teachers, Oshagbemi (1997) used a questionnaire comprising eight basic job elements. The job elements were listed in Fig. 5.2. Respondents were asked to indicate the level of satisfaction or dissatisfaction with which they derived from each of the aspects considered.

Conceptual model 3 of academic staff job satisfaction (Adapted from: Oshagbemi (1997)

Verhaegen (2005) analysed the recruitment and retention of academic talent, as the most important factors for the success and competitiveness of a business school. With respect to faculty, the most important factors from both recruitment and a retention perspective were academic freedom, research time, geographic location of the school and opportunities for professional development. The important factors for faculty were institutional factors, specifically reputation of the school, innovativeness and progressiveness of the school and international orientation. In the case of deans, the most important factors for recruitment of faculty were reputation of the school in the academic community, innovativeness and progressiveness of the school, stimulating peer community and research time. For retention, the most important factors were academic freedom, recognition of research achievements and career opportunities (please see Table 5.6).

According to Verhaegen (2005, p. 815), the results of academic job satisfaction “[…] could not only help the school in identifying its main bottlenecks in the recruitment and retention of academic talent, but it can also help the school to assess its competitive position and identify its unique selling points and help to design an effective profiling strategy”.

Another conceptual model is that of Houston et al. (2006) (please see Fig. 5.3). The figure shows a clear relationship between some dimensions of academic staff job and their job satisfaction.

3.2 Suggested Model for Faculty Satisfaction

In our study, the research team proposed a conceptual model derived from some of the best known models in the literature, such as those described above. Figure 5.4 shows the model, in which it was hypothesized that some dimensions – teaching climate, management, colleagues, non-academic staff, physical work environment, conditions of employment, personal and professional development, institutions’ culture and values, institutions’ prestige and research climate – have an impact on academic staff satisfaction. Moreover, the conceptual model shows the relationship between satisfaction and motivation. This relationship was demonstrated by several authors. The literature also shows that job satisfaction is closely connected to employees’ motivation. Herzberg et al. (1959) have already stressed the need to strengthen motivators in order to engender career satisfaction. In like manner, Dinham and Scott (1998, p. 362–363) stated that “Satisfaction and motivation are […] inextricably linked through the influence each has on the other.” Higher levels of motivation have been considered as a positive outcome of job satisfaction (Sledge et al. 2008).

4 Methodological Approach

A nation-wide study emerges in the context of the Project PTDC/ESC/67784/2006 – An Examination of Academic Job Satisfaction and Motivation in Portuguese Higher Education, financed by the Foundation for Science and Technology.

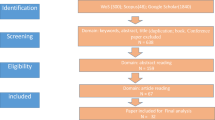

In this chapter, we present results derived from quantitative data gathered through an on-line survey (please see Appendix 2). Before the application of the survey, the research team applied three Focus Groups to ascertain the factors of satisfaction/dissatisfaction and motivation/amotivationFootnote 4 of academic staff. The information collected was used in the construction of the questionnaire. Thus, the survey gives rise to the literature review for this theme and from the preoccupations expressed by faculty members/participants in the Focus Groups. The on-line survey was accessible to all faculty members, including all sub-groups (professor, researcher, part-time, full-time, etc.) for all institutional types of Portuguese HEIs public-private, university-polytechnic, etc.). Here we will only present results about academics in public higher education institutions.

The satisfaction dimensions considered were: Teaching Climate; Management of the Institution/Department/Unit; Colleagues; Non Academic Staff (administrative staff, technical and laboratory staff); Physical Work Environment; Conditions of Employment; Personnel and Professional Development; Institutions’ Culture and Values; Institutions’ Prestige; and Research Climate. Those dimensions to examine the academic staff job satisfaction were defined accordingly to the literature review. The aspects mentioned by academics during the Focus Groups were also covered by these dimensions. Therefore, each satisfaction dimension is composed of factors of satisfaction/dissatisfaction identified in the literature review and considered by the academics in the Focus Groups. The instrument was available to all Portuguese academics on the website http://questionarios.ua.pt/index.php?sid=19766&lang=pt. This address was sent to all Portuguese HEIs in year 2010 and all academics invited to participate:

In order to have a vast divulgation of the survey among the faculty members, several efforts were pursued. Therefore, all the faculty members were invited to participate in many different ways:

-

1.

Communiqués were sent to the Council of Rectors of Public Universities (CRUP), Council of Presidents of Public Polytechnics (CCISP) and Portuguese Association of Private Higher Education (APESP) informing them about the study and requesting their help in the dissemination of the study;

-

2.

A letter was sent to all Rectors and Presidents of both public and private universities as well as polytechnic institutes requesting that the link to the survey was sent to the faculty members in their institutions;

-

3.

Also the link to the survey was sent to the three faculty unions;

-

4.

All the steps above were repeated thrice in order to increase the response rate.

On average, the response time was 25 min. Because the questionnaire was long, some people gave up halfway through the fill which is often common in online surveys. In Portuguese higher education, according to the last statistics available at the time the survey was launched (2009), there were 36215 academics (PORDATA 2011; GPEARI 2011). The response rate obtained was about 12.5 % – a total of 4529 academics participated in the study, a response rate that is much higher than usual in a study of national dimension and administered online.

The results relate only to the academics that work in public higher education institutions (universities and polytechnics) and agreed to answer the online questionnaire (the total of 2544 academics). The response was free and spontaneous.

Most respondents to the survey work in public universities 54.1 %. With regard to age groups, respondents are concentrated in age groups “41–50 years” (38.2 %), “31–40 years” (28 %) and “51–60 years” (23.7 %). It should be noted that, on average, the age of respondents were 45 years with the mode range of 44 years. Considering the distribution of the respondents by gender, we can verify that 50.7 % of them are men and 49.3 % are women. There are, therefore, slightly more men than women among the respondents. Finally, with respect to the academic rank in Portuguese higher education, a higher proportion of respondents are “Juniors” (58.4 %). Only 15.5 % of the academics respondents are “Seniors”. With respect to academics by institutional type and academic rank, the sample and the population present the following configuration: (Table 5.7)

As noted, there are marked and statistically significant differences between the sample and the population, preventing, therefore, to generalize any conclusions.Footnote 5 That is, comparisons between academic ranks and institutional type, which we proceed to in this work, do not reflect more than the opinions and attitudes of academics who responded to the questionnaire.

5 Results

5.1 Satisfaction with Teaching Climate by Institutional Type

With regard to satisfaction with Teaching Climate in public polytechnic institutes and in public universities, only the indicator “training of students” records mean below the centre of the scale (5) which is interpreted, therefore, as dissatisfaction. The “degree of autonomy in teaching practice” is the indicator with which academics are more satisfied (Fig. 5.5). Research shows that autonomy and academic freedom have been particularly expensive for teachers, although some have referred to it with a sense of nostalgia (Ylikoji 2005), and others referring to the major constraints that have been felt in academic work and on professional autonomy (Barrier and Musselin 2009). Moreover, the previous preparation of students as well as the way on how it occurs in the transition from secondary education to higher education have been considered crucial to the success of students at the beginning of higher education (Brites Ferreira et al. 2011, 2012a, b; Seco et al. 2006).

5.2 Satisfaction with Management of the Institution/Department/Unit by Institutional Type

The satisfactory means with the Management of the Institution/Department/Unit is higher in public polytechnic institutes, when compared with satisfaction in public universities. In public universities, academics are dissatisfied with almost all indicators: with the ability of managers to innovate, with management’s response to faculty needs, with time that managers take to respond to these needs and to communicate with managers. The satisfaction with the managers of the department/organizational unit registers the highest values but around the centre of the scale, as shown in the following figure. With respect to this dimension and with consideration of the satisfaction levels of the academics, it seems to us that the data suggest that there is quite some way to go with regard to possible improvements in the management of the institutions, their departments and their units (Fig. 5.6).

5.3 Satisfaction with Colleagues by Institutional Type

Regarding satisfaction with Colleagues, the indicators “interaction between faculty members of different courses” and “cooperation with colleagues from different departments/units” record lower values, especially in public universities. The satisfaction with scientific quality, skills and pedagogic quality of the faculty registers the highest values, as was shown in the following figure. These results suggest that improvements are possible, particularly in terms of cooperation and interaction between academics of different departments or disciplines. Although the data may also reflect competition among academics or between areas and departments in which they are; this is related to managerial trends that have been felt in higher education (Lima 2012; Magalhães and Santiago 2012) (Fig. 5.7).

5.4 Satisfaction with Non Academic Staff (Administrative Staff, Technical and Laboratorial Staff…) by Institutional Type

The satisfaction with cooperation, with administrative staff and technical and laboratory staff registers the highest values. Academics express less satisfaction with the adequacy of the number of non academic staff to the amount of existing work. In public universities, they are dissatisfied with this aspect (mean is below the centre of the scale) (Fig. 5.8).

5.5 Satisfaction with Physical Work Environment by Institutional Type

Regarding satisfaction with Physical Work Environment, only the indicators “existence of an area to monitor the students” and “equipment available to faculty and their families” record means below the centre of the scale (5) and are interpreted, therefore, as dissatisfaction, especially in public universities. The “cleanup of the institution” and the “size of classrooms” are the indicators with which academics are more satisfied (Fig. 5.9). From these results emerges the fact that HEIs cannot dispose of support facilities, including kindergartens. Academics spend a lot of time in institutions or in classes or meetings and administrative work with obvious prejudices family (Forest 2002). Still, another reason for dissatisfaction of the academics is lack of spaces for student attendance. The authors of this book for personal knowledge supports this evidence. Many faculty share offices (sometimes there are 3, 4 or more teachers per cabinet) which naturally complicates the personalized attention to the student.

5.6 Satisfaction with Conditions of Employment by Institutional Type

Regarding satisfaction with Conditions of Employment, in public universities and public polytechnic institutes, the satisfaction mean is below the centre of the scale of the three indicators (“remuneration”, “job security” and “career opportunities”). This means that academics are dissatisfied with this dimension, and more dissatisfied in particular with career opportunities (indicator that registered the lowest mean: 3.7) (Fig. 5.10). Indeed, Portuguese academics are overall more satisfied with intrinsic aspects of job and dissatisfied with the extrinsic aspects of the job, such as the characteristics of employment considered in this study. This dissatisfaction with extrinsic aspects of the job is well documented in scientific literature (Ward and Sloane 2000).

5.7 Satisfaction with Personal and Professional Development by Institutional Type

Academics in public universities and public polytechnic institutes seem to be reasonably satisfied with the dimension “Personal and Professional Development” (means registered are close to the centre of the scale) (Fig. 5.11). These data confirm that, despite its importance, it is not always easy to reconcile the professional aspects of career development with personal life or family (Santos 2007; Brites Ferreira et al. 2011, 2012a, b).

5.8 Satisfaction with Institutions’ Culture and Values by Institutional Type

Academics are more satisfied with the academic freedom they have. Academics in public universities are dissatisfied with the ability to innovate in the institution (mean = 4.8) and with the participation of faculty in decision-making processes (mean = 4.6) (Fig. 5.12). As a result of the research, academic freedom is highly valued by academics. However, if we consider the other two indicators mentioned, we may wonder if we are not before some critical attitude towards innovation of institutions and participation of the academic staff in decision-making processes. With regard to the latter aspect, it is important to note that the legal regime of IES, approved by Law no. ° 62/2007 of 10 September, has provided conditions for the existence of more uninominal bodies, to the detriment of collegial bodies and elected bodies.

5.9 Satisfaction with Institutions’ Prestige by Institutional Type

With respect to satisfaction with Institutions’ Prestige, all indicators (“prestige of the institution”, “efforts of the institution to improve its image”, “international partners of the institution”, “national partners of the institution”) registered satisfaction means slightly above the centre of the scale, which means that academics in public higher education institutions are satisfied but not very satisfied with this dimension (Fig. 5.13).

5.10 Satisfaction with Research Climate by Institutional Type

Regarding satisfaction with Research Climate, in public universities and public polytechnic institutes, only the indicator “research outputs” records means above the centre of the scale (5) in both institutional types. This is, therefore, the indicator with which academics are more satisfied. Dissatisfaction is higher with financial resources to do research, but academic staff is also dissatisfied with logistical conditions to do research, research time, recognition by the institution of the research work and opportunities to do research (Fig. 5.14).

Research in higher education in Portugal was “marginal” before the Revolution of April 1974. The relationship between research and teaching was reinforced by law (Decree-Law 448/79) in universities. It then becomes clear that academics have assumed the three traditional missions of the university: teaching, research and services to society, together with duties in terms of institutional governance and academic management at all organizational levels. Later, a similar law was approved for the polytechnic institutes (Decree-Law 185/81) (Santiago et al. 2013). Thus, research is a relatively recent requirement in the academic career. On the other hand, we must associate the current state of economic and financial constraints that have been reflected in research funding.

5.11 Overall Satisfaction by Institutional Type

Overall Satisfaction of academics were higher with the indicators “adequacy of skills to the teaching practice” and “job”, in public universities and public polytechnic institutes. Less satisfaction (but not dissatisfaction) was expressed by academics with the “institution”. The satisfactory means are higher in public polytechnic institutes, except with respect to the indicator “opportunity to update knowledge” as shown in Fig. 5.15. The literature shows, similar to what happens in our study, positive levels of satisfaction among teachers (Oshagbemi 1999; Ward and Sloane 2000).

5.12 Overall Motivation by Institutional Type

Regarding Overall Motivation, academics are more motivated to teach and to remain as faculty members in higher education in public universities and public polytechnic institutes. They are less motivated to serve the community and to participate in the governing bodies in public universities and public polytechnic institutes. Demotivation to participate in the governing bodies was shown by academics in public universities (only this indicator records a motivation mean below the centre of the scale in public universities, interpreted as demotivation) (Fig. 5.16). These results are similar to those of several studies which indicate that the preferences of the academics are primarily for teaching activities, then to research and ultimately to management (McInnis 2000a, b; Oshagbemi 2000; Verhaegen 2005).

5.13 Satisfaction with Teaching Climate, Management, Colleagues and Work environment: A Structural Equation Model

As shown in the following figure, the indicators are well explained by their latent dimensions, all are statistically significant and the correlations between the dimensions (latent variables) are high (rs>=0,7), positive and statistically significant (Fig. 5.17). More information is provided on Appendix 1 (please see Tables 5.8, 5.9, 5.10, 5.11, 5.12, 5.13, 5.14, 5.15, 5.16, 5.17, 5.18, and 5.19).

5.14 Synthetic Indexes

The dimensions of satisfaction and motivation are synthetic indexes constructed using a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with a single dimension.Footnote 6 The factorial scores - standardized values, after unstandardizedFootnote 7 – are the individual index scores. Based on the respective indicators, we have constructed the following dimensions of satisfaction and motivation:

-

Satisfaction with Teaching ClimateFootnote 8

-

Satisfaction with Management of the Institution/Department/UnitFootnote 9

-

Satisfaction with ColleaguesFootnote 10

-

Satisfaction with Physical Work EnvironmentFootnote 11

-

Satisfaction with Non academic staff (administrative staff, technical and laboratorial staff…)Footnote 12

-

Satisfaction with Conditions of EmploymentFootnote 13

-

Satisfaction with Personal and Professional DevelopmentFootnote 14

-

Satisfaction with Institutions’ Culture and ValuesFootnote 15

-

Satisfaction with Institutions’ PrestigeFootnote 16

-

Overall SatisfactionFootnote 17

-

Overall MotivationFootnote 18

As can be observed, only academics in public polytechnic institutes reveal satisfaction values above the mean, in the dimensions Physical Work Environment and Management of the Institution/Department/Unit, and also Overall Motivation is above the mean (Fig. 5.18).

Synthetic indexes by institutional type

Significant statistical differences in Teaching Climate (t(2407) = −2.901; p < 0.05);

Significant statistical differences in Management (t(2292) = −7.417; p < 0.05);

Significant statistical differences in Colleagues (t(2339) = −2.946; p < 0.05);

Significant statistical differences in Physical Work Environment (t (1127) = −3.545; p < 0.05;

Significant statistical differences in Non academic staff (t(1940) = −2.719; p < 0.05);

No significant statistical differences in Conditions of Employment (t(2468) = 0.798; p > 0.05);

No significant statistical differences in Personal and Professional Development (t(2493) = 0.094; p > 0.05);

Significant statistical differences in Institutions’ Culture and Values (t(2429) = −2.371; p < 0.05);

Significant statistical differences in Institutions’ Prestige (t(2351) = 2.247; p < 0.05);

No significant statistical differences in Overall Satisfaction (t(2376) = −1.517; p > 0.05);

Significant statistical differences in Overall Motivation (t(2390) = −5.648; p < 0.05)

Regarding synthetic indexes by academic rank, there are not significant statistical differences between juniors and seniors with respect to their overall motivation and their overall satisfaction. The significant statistical differences are only between seniors and juniors with respect to their satisfaction with conditions of employment; personal and professional development, being seniors more satisfied than juniors and with respect to their satisfaction with management and colleagues, being juniors more satisfied than seniors (Fig. 5.19).

Synthetic indexes by academic rank

Significant statistical differences in Teaching Climate (t(2042) = 2.169; p < 0.05);

Significant statistical differences in Management (t(2248) = −2.603; p < 0.05);

Significant statistical differences in Colleagues (t(2287) = −2.096; p < 0.05);

No significant statistical differences in Physical Work Environment (t(1108) = −1.153; p > 0.05);

No significant statistical differences in Non academic staff (t(1902) = −0.132; p > 0.05);

Significant statistical differences in Conditions of Employment (t(2411) = 12.013; p < 0.05);

Significant statistical differences in Personal and Professional Development (t(2437) = 5.167; p < 0.05);

No significant statistical differences in Institutions’ Culture and Values (t(2377) = 0.936; p > 0.05);

No significant statistical differences in Institutions’ Prestige (t(2299) = 0.795; p > 0.05);

No significant statistical differences in Overall Satisfaction (t(2326) = 1.148; p > 0.05);

No significant statistical differences in Overall Motivation (t (2339) = −0.334; p > 0.05)

Regarding synthetic indexes by gender, there are not significant statistical differences between men and women with respect to their overall satisfaction, their satisfaction with institutions’ culture and values, conditions of employment, non academic staff and physical work environment.

There are significant statistical differences between men and women with respect to their overall motivation, their satisfaction with teaching climate, management, colleagues, personal and professional development, institution’s prestige (please see Fig. 5.20).

Synthetic indexes by gender

Significant statistical differences in Teaching Climate (t(2383) = −2.162; p < 0.05);

Significant statistical differences in Management (t(2271) = 2.684; p < 0.05);

Significant statistical differences in Colleagues (t(2317) = 2.187; p < 0.05);

No significant statistical differences in Physical Work Environment (t(1116) = 0.060; p > 0.05);

No significant statistical differences in Non academic staff (t(1921) = −0.408; p > 0.05);

No significant statistical differences in Conditions of Employment (t(2443) = −0.368; p > 0.05);

Significant statistical differences in Personal and Professional Development (t(2470) = −4.433; p < 0.05);

No significant statistical differences in Institutions’ Culture and Values (t(2406) = −0.013; p > 0.05);

Significant statistical differences in Institutions’ Prestige (t(2328) = 2.606; p < 0.05);

No significant statistical differences in Overall Satisfaction (t(2354) = −1.139; p > 0.05);

Significant statistical differences in Overall Motivation (t(2367) = 2.648; p < 0.05)

5.15 Satisfaction and Motivation

The following figure shows the relationship between the dimensions of satisfaction and academic motivation (Fig. 5.21).

The model explains that 35 % of the variation are motivated to teach, 41 % of the variation are motivated to work in the institution and 50 % of the variation are motivated to remain as a faculty member in higher education. Only the relationship between “Satisfaction with Physical Work Environment” and “Motivation to Work in the Institution” is not statistically significant.

6 Interviews

In the survey cited above, interviews were also made with policy makers, (including former ministers, former directors, former presidents and current presidents and rectors of HEI) and human resource managers of HEI. Some questions and answers were directly related to academic work and academic career. Despite the diversity of responses, there are issues that reappear throughout the interviews, particularly when they are about motivation and satisfaction of the academics.

Talking about what motivates academics, respondents refer mainly the following aspects: research, teaching, good environment, exchange with other communities, international acknowledgement and appreciation, freedom and autonomy, social position, self-motivation, working conditions, payment. On other hand, referring to what discourages academics, respondents highlight the following aspects: uncertainty, job insecurity/lack of stability, excessive administrative work, lack of real conditions for career progression, lack of time and conditions for research, poor organizational climate, increased bureaucracy, difficulties to create research teams, and lack of commitment to student success, reward, no recognition of bureaucratic work.

Regarding the existing dissatisfaction of academics, respondents report that it is due mainly to the following reasons: too much bureaucracy, contract instability, payment, difficulties in promotions/career, differential treatment, not recognizing the merits of teaching, lack of research funding, lack of resources, lack of technological resources, lack of student motivation. On other hand, in relation to the satisfaction, they report the following aspects: recognition/appreciation of the work results/merit, research, good working conditions, organizational support, stability in employment, payment, flexible timetable work, training support, career progression, freedom and autonomy, exchange and dialogue between communities, merit awards performance, student’s success and/or motivation of students.

There are several studies related to academic work and satisfaction on several professional roles that characterise the academic work (Dowd and Kaplan 2005; Hagedorn 2000; Hermanowicz 2003; McInnis 2000a, b; Rosser 2005; Ssesanga and Garrett 2005; Stevens 2005; Taylor 2008; Teichler 2012; Verhaegen 2005; Winter and Sarros 2002; Ylikoji 2005). In general, these studies indicate high levels of satisfaction with aspects intrinsic to academic work, such as the content of academic activities (with particular reference to the case of research), freedom and autonomy in planning and organizing the work itself. Dissatisfaction appears associated with material and financial conditions of work, as well as dimensions related to the work in this heightened competition among colleagues and the deterioration of relations of collegiality, lack of human and material support for performing an increasing number of administrative tasks. These studies also warn the degradation of working conditions of academics and a general increase in stress levels in the academic career. These constraints and unrealistic expectations in terms of performance of the various professional roles are aspects mentioned by a large number of academics, as relevant to the decreased quality of life at work.

The present statutes of academic career enunciate explicitly functions of teaching, research, service to the community and management. Moreover, they allow a number of other tasks that are regulated by each HEI. Thus, academics are facing changes and challenges. On the one hand, these changes and challenges refer to the complementarity between the various activities. On the other hand, the question of competition between the activities is also present. Indeed, these activities have a different value in the organization and management of academic careers. As stated by the authors such as McInnis (2000a, b); Taylor (2008) the perception of the importance of different professional roles for the promotion system shapes the everyday working practices and career planning by academics.

Given the diversity of roles currently assigned to academics and the changes that have been happening in higher education it will be natural that the academic profession in Portugal, will be faced with moments of uncertainty, insecurity and challenges.

7 Analysis

7.1 Dimensions of Job Satisfaction

Academic staff expresses more satisfaction with “Non academic staff (administrative staff, technical and laboratory staff)”, “Teaching Climate” and “Colleagues”. On the contrary, academics reveal less satisfaction or dissatisfaction with “Research Climate” and “Conditions of Employment”. These results are similar to Ssesanga and Garrett (2005) conclusions – academics were relatively satisfied with the co-worker behaviour and intrinsic factors of teaching. Also Ward and Sloane (2000) have stated similar results: academics were most satisfied with the opportunity to use their own initiative, with the relationship with their colleagues and with the actual work; they were least satisfied with promotion prospects and salary.