Abstract

Europe has not done well in the years since the 2008 crisis, with a double dip recession and a recovery far slower than that of the US from whence the crisis came. Among the key reasons for this dismal performance is the euro, or more precisely, the structure of the Eurozone, the institutions, rules, and regulations that were created to ensure growth and stability of a single currency amongst a diverse set of countries—and the failure to do some of the things (like the establishment of a common deposit insurance system) that should have been done. The paper describes how Europe created a divergent system, with increasing disparities between the richer and poorer countries, and the role of certain beliefs, prevalent at the time, but since questioned, about what makes for good economic performance.

Excerpt of the chapter “Crises: Principles and Policies: With an Application to the Eurozone Crisis,” in Life After Debt: The Origins and Resolutions of Debt Crisis, Joseph E. Stiglitz and Daniel Heymann (eds.), Houndmills, UK and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. Permission granted by the Author and rights acquisition to the Publisher.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

The euro was a political project, conceived to help bring the countries of Europe together. It was widely recognized at the time that Europe was not an optimal currency area.Footnote 1 Labor mobility was limited, the countries’ economies experienced different shocks, and there were different long-term productivity trends. While it was a political project, the politics was not strong enough to create the economic institutions that might have given the euro a fair chance of success. The hope was that over time, this would happen. Bur, of course, when things were going well, there was little impetus to “complete” the project, and when a crisis finally occurred (with the global recession that began in the United States in 2008) it was hard to think through carefully what should be done to ensure the success of the euro.

I and others who supported the concept of European integration hoped that when Greece went into crisis, in January, 2010, decisive measures would be taken that would demonstrate that the European leaders at least understood that further actions would be needed to enable the euro to survive. That did not happen, and quickly, a project designed to bring Europe together became a source of divisiveness. Germans talked about Europe not being a transfer union—a euphemistic and seemingly principled way of saying that they were uninterested in helping their partners, as they reminded everyone of how they had paid so much for the reunification of Germany. Not surprisingly, others talked about the high price they had paid in World War II. Selective memories played out, as Germans talked about the dangers of high inflation; but was it inflation or high unemployment that had brought on the political events that followed?

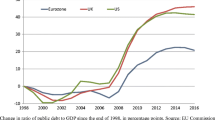

Greece was castigated for its high debts and deficits, and it was natural to blame the crisis on excessive profligacy, but again there was selective memory: In the years before the crisis bit Spain and Ireland had low debt to GDP ratios and a fiscal surplus. No one could blame the crisis that these countries faced on fiscal profligacy. It was thus clear that Germany’s prescription, that what was required were stronger and more effectively enforced fiscal constraints, would not prevent a recurrence of crisis, and there was good reason to believe that stronger constraints—austerity—would make the current crisis worse. Indeed, by so manifestly showing that Europe’s leaders did not understand the fundamentals underlying the crisis—or that if they did, by manifesting such enormous resistance to undertaking the necessary reforms in the European framework—they almost surely contributed to the markets’ lack of confidence, helping to explain why each of the so-called rescue measures was viewed as only a temporary palliative.

In the remainder of this section, I describe several of the underlying structural properties of the Euro Zone that, if they do not make crises inevitable, certainly make them more likely to occur. (What is required is not so much the structural adjustment of the individual countries, but the structural adjustment of the euro framework.) Many of these were rules that reflected the neoclassical model, with the associated neoliberal policy prescriptions, which were fashionable (in some circles) at the time of the creation of the euro. Europe made two fundamental mistakes: first, it enshrined in its “constitution” these fads and fashions, the concerns of the time, without providing enough flexibility in responding to changing circumstances and understandings. And secondly, even at the time, the limits of the neoclassical model had been widely exposed—the problems posed, for instance, by imperfect competition, information, and markets to which I alluded earlier. The neoclassical model failed to recognize the many market failures that require government intervention, or in which government intervention would improve the performance of the economy. Thus, most importantly from a macroeconomic perspective, there was the belief that so long as the government maintained a stable macro-economy—typically interpreted as maintaining price stability—overall economic performance would be assured. By the same token, if the government kept budgets in line (kept deficits and debts within the limit set by Maastricht Convention) the economies would “converge,” so that the single currency system would work. The founders of the Euro Zone seemed to think that these budgetary/macro-conditions were necessary and essentially sufficient for the countries to converge, that is, to have sufficient “similarity” that a common currency would work. They were wrong. The founders of the Euro Zone were also focused on government failure, rather than market failure, and thus they circumscribed governments, setting the stage four the market failures that would bring on the euro crisis.

Much of the framework built into the Euro Zone would have enhanced efficiency, if Europe had gotten the details right and if the neoclassical model were correct. But the devil is in the detail, and some of the provisions, even within the neoliberal framework, led to inefficiency and instability.

Free mobility of factors without a common debt leads to the inefficient and unstable allocation of factors. The principle of free mobility is to ensure that factors move to where (marginal) returns are highest, and if factor prices are equal to marginal productivity, that should happen. But what individuals care about, for instance, is the after-tax returns to labor, and this depends not only on the marginal productivity of labor (in the neoclassical model) but also on taxes and the provision of public goods. Taxes, in turn, depend in part on the burden imposed by inherited debt. Ireland, Greece and Spain face high levels of inherited debt. In these countries, the incentive for outmigration, and is especially so, because that debt did not increase to its current levels as a result of investments in education, technology, or infrastructure that is, through the acquisition of assets, but rather as a result of financial and macro-economic mismanagement. This implies migration away from these highly indebted countries to those with less indebtedness, even when marginal productivities are the same; and the more individuals move out, the greater the “equilibrium” tax burden on the remainder, accelerating the movement of labor away from an efficient allocation.Footnote 2 (Of course, in the short run, migration may have positive benefits to the crisis country, both because it reduces the burden of unemployment insurance, and as the remittances back home provide enhanced domestic purchasing power. Whether in the short run these “benefits” to migration out-weight the adverse effects noted above is an empirical question. The migration also hides the severity of the underlying downturn, since it means that the unemployment rate is less, possibly far less, than it otherwise would be.)Footnote 3

Free mobility of capital and goods without tax harmonization can lead to an inefficient allocation of capital and/or reduce the potential for redistributive taxation, leading to high levels of after-tax and transfer inequality. Competition among jurisdictions can be healthy, but there can also be a race to the bottom. Capital goes to the jurisdiction which taxes it at the lowest rate, not where its marginal productivity is the highest. To compete, other jurisdictions must lower the taxes they impose on capital, and since capital is more unequally distributed than labor, this reduces the scope for redistributive taxation. (A similar argument goes for the allocation of skilled labor.) Inequality, it is increasingly recognized, is not just a moral issue: it also affects the performance of the economy in numerous ways (Stiglitz 2012).

Free migration might result in politically unacceptable patterns of location of economic activity. The general theory of migration/local public goods has shown that decentralized patterns of migration may well result in inefficient and socially undesirable patterns of location of economic activity and concentrations of population. There can be congestion and agglomeration externalities (both positive and negative) that arise from free migration. That is why many countries have an explicit policy for regional development, attempting to offset the inefficient and/or socially unacceptable patterns emerging from unfettered markets.

In the context of Europe, free migration (especially that arising from debt obligations inherited from the past) may result in a depopulation not only of certain regions within countries but also of certain countries. One of the important adjustment mechanisms in the United States (which shares a common currency) is migration; and if such migration leads to the depopulation of an entire state, there is limited concern.Footnote 4 But Greece or Ireland are, and should be, concerned about the depopulation of their countries.

The single market principle for financial institutions and capital too can lead to a regulatory race to the bottom, with at least some of the costs of the failures borne by other jurisdictions. The failure of a financial institution imposes costs on others (evidenced so clearly in the crisis of 2008), and governments will not typically take into account these cross-border costs. That is why either there has to be regulation by the host country (Stiglitz et al. 2010), or there has to be strong regulation at the European level.

Worse still, confidence in any country’s banking system rests partially in the confidence of the ability and willingness of the bank’s government to bail it out (and/or to the existence of institutional frameworks that reduce the likelihood that a bailout will be necessary, that there are funds set aside should a bailout be necessary, and that there are procedures in place to ensure that depositors will be made whole). Typically, there is an implicit subsidy, from which banks in jurisdictions with governments with greater bailout capacity benefit. Thus, money flowed into the United States after the 2008 global crisis, which failures in the United States had brought about, simply because there was more confidence that the United States had the willingness and ability to bail out its banks. Similarly, today in Europe: what Spaniard or Greek would rationally keep his money in a local bank, when there is (almost) equal convenience and greater safety in putting it in a German bank?Footnote 5 Only by paying much higher interest rates can banks in those countries compete, but such an action would put them at a competitive disadvantage; and the increase in interest rates that is required may be too great—the bank would quickly appear to be non-viable. What happens typically is capital flight (or, in the current case, what has been described as a capital jog: the surprise is not that capital is leaving, but that it is not leaving faster). But that sets into motion a downward spiral: as capital leaves, the country’s banks restrict lending, the economy weakens, the perceived ability of the country to bail out its banks weakens, and capital is further incentivized to leave.

There are two more fallacies that are related to the current (and inevitable) failures of the Euro Zone. The first is the belief that there are natural forces for convergence in productivity, without government intervention. There can be increasing returns (reflected in clustering), the consequence of which is that countries with technological advantages maintain those advantages, unless there are countervailing forces brought about by government (industrial) policies. But European competition laws prevented, or at least inhibited, such policies.Footnote 6

The second is the belief that necessary, and almost sufficient, for good macro-economic performance is that the monetary authorities maintain low and stable inflation. This led to the mandate of the European Central Bank to focus on inflation, in contrast to that of the Federal Reserve, whose mandate includes growth, employment, and (now) financial stability. The contrasting mandates can lead to an especially counterproductive response to a crisis, especially one which is accompanied by cost-push inflation arising from high energy or food prices. While the Fed lowered interest rates in response to the crisis, the continuing inflationary concerns in Europe did not lead to matching reductions there. The consequence was an appreciating euro, with adverse effects on European output. Had the ECB taken actions to weaken the euro, it would have stimulated the economy, partially offsetting the effects of austerity. As it was, it allowed the US to engage in competitive devaluation against it.

It also meant that the ECB (and central banks within each of the member countries) studiously avoided doing anything about the real estate bubbles that were mounting in several of the countries. This was in spite of the fact that the East Asian crisis had shown that private sector misconduct—even when there is misconduct in government—could lead to an economic crisis. Europe similarly paid no attention to mounting current account balances in several of the countries.

Ex post, many policymakers admit that it was a mistake to ignore these current account imbalances or financial market excesses. But the underlying ideology then (and still) provides no framework for identifying good “imbalances,” when capital is flowing into the country because markets have rationally identified good investment opportunities, and those that are attributable to market excesses.

Notes

- 1.

See Mundell (1961).

- 2.

- 3.

By the same token, if some of the burden of taxation is imposed on capital, it will induce capital to move out of the country.

- 4.

Some see an advantage: buying influence over that country’s senators because less expensive.

- 5.

The exit from Spanish banks while significant—and leading to a credit crunch—has been slower than some had anticipated. This in turn is a consequence of institutional and market imperfections (for example, rules about knowing your customer, designed to limit money laundering), which interestingly the neo-classical model underlying much of Europe’s policy agenda ignored. There is far less of a single market than it is widely thought.

- 6.

References

Lin JY (2012) New structural economies: a framework for rethinking development policies. The World Bank, Washington, DC

Mundell R (1961) A theory of optimum currency areas. Am Econ Rev 51(4):657–665

Stiglitz JE (1977) Theory of local public goods. In: Feldstein MS, Inman RP (eds) The economics of public services. Macmillan Press, London, pp 274–333 (Paper presented to IEA Conference, Turin, 1974)

Stiglitz JE (1983a) The theory of local public goods twenty-five years after Tiebout: a perspective. In: Zodrow GR (ed) Local provision of public services: the Tiebout model after twenty-five years. Academic, New York, pp 17–53

Stiglitz JE (1983b) Public goods in open economies with heterogeneous individuals. In: Thisse JF, Zoller HG (eds) Locational analysis of public facilities. North-Holland, Amsterdam, pp 55–78

Stiglitz JE (2012) The price of inequality. W. W Norton, New York (Spanish edition published by Taurus)

Stiglitz JE, Lin JY (eds) (2013a) The industrial policy revolution I: the role of government beyond ideology. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Stiglitz JE, Lin JY (eds) (2013b) The industrial policy revolution II: Africa in the 21st century. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Stiglitz JE, Sen A, Fitoussi JP (2010) Mismeasuring our lives: why GDP doesn’t add up. The New York Press, New York

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Stiglitz, J.E. (2017). The Fundamental Flaws in the Euro Zone Framework. In: da Costa Cabral, N., Gonçalves, J., Cunha Rodrigues, N. (eds) The Euro and the Crisis. Financial and Monetary Policy Studies, vol 43. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45710-9_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45710-9_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-45709-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-45710-9

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)