Abstract

Short of studying actual new venture launches, what could possibly be more potent than understanding the preconditions that enable entrepreneurial activity? Early research focused unsurprisingly on behavior (the “what?” and the “how?” even somewhat the “where?” and the “when?”) and since entrepreneurs were obviously special people, on the entrepreneurial person (the “who?”). Intentions are classically defined as the cognitive state temporally and causally prior to action (e.g., The intentional stance, Cambridge, 1989; Entrep Theory Pract 24:5–23, 2000). Here that translates to the working definition of the cognitive state temporally and causally prior to the decision to start a business. The field has adopted and adapted formal models of entrepreneurial intentions that are based on strong, widely accepted theory and whose results appear not only empirically robust but of great practical value. But do we have what we think we have? Or have we also opened the door to a much broader range of questions that will advance our theoretical understanding of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurs? We offer here a glimpse of the remarkably wide array of fascinating questions for entrepreneurship scholars.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Plan Behavior

- Implementation Intention

- Entrepreneurial Intention

- Entrepreneurial Behavior

- Reciprocal Causation

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 A Note to Educators and Practitioners

While this chapter is designed to spur more and better research into entrepreneurial intentions, the discussions here have significant value to practice and especially to the classroom. Throughout the chapter you will see direct comments about the practical and pedagogical implications of the issues under discussion. If we cannot serve our scholarly colleagues, our entrepreneurial colleagues, and our educator colleagues, this book misses a great opportunity and we all choose not to do so.

In classrooms and communities, we seek to develop more entrepreneurial students and trainees, we seek to develop better entrepreneurs. Part of that is raising their intentions to start a business; another part is making their intentions more realistic. To do both requires a deeper, richer understanding of the dynamic process by which entrepreneurial intentions evolve. As you will see, we have recently uncovered intriguing new knowledge about this that can be readily applied (and our scholarly friends will find most intriguing as well.)

2 A Critical Overview of Intentions and Entrepreneurial Intentions

2.1 Do Intentions Even Exist?

Consider an experiment. The subject is wired up and the experimenter asks the subject to raise either hand. Interestingly, the experimenter can quickly discern which hand the subject will raise before subjects are aware themselves. Next, the experimenter induces the subject to raise either the left or right hand. However, the subject nonetheless perceives the choice as free will, even after being informed of the procedure. A neuroscientist can see our intentions before we perceive we have formulated them? We perceive intent toward a discrete behavior even where it is completely illusory? What does this mean for our models and measures of entrepreneurial intentions that we have carefully developed from proven theory and refined through rigorous empirical analysis? (Libet et al. 1983)

2.1.1 A Little History

The rush to describe this amazing phenomenon was like any nascent field of study: It tends to favor description over theory. However, if we are to answer the “Why?” question, we need theory. In remarkably short order, the field of entrepreneurship developed a broad, rich body of observational data that allowed entrepreneurship scholars to begin asking some very intriguing questions of value to scholar and practitioner alike. That success, coupled with the compelling subject matter, allowed the field to increase in breadth. However, the scarcity of well-developed theory was beginning to take its toll. And even where scholars had drawn on theory, they drew upon logical but deeply flawed domains such as personality psychology.

We then saw the entry of serious social psychology and, later, cognitive psychology and developmental psychology. Whatever the gestation processes of new ventures, the sequence of behaviors need not follow any optimal pattern, but the theories offered by social and cognitive (and developmental) psychology immediately provided testable models that seemed quite relevant to entrepreneurship.

For example, the field once upon a time referred to “budding” entrepreneurs, etc., and like much of the early work on the closely related topic of opportunity recognition, the work was atheoretic “dustball empiricism” that rarely moved past ad hoc descriptive studies that were all too often unreplicable. Given that a specific class of intentions models (the Fishbein–Ajzen models) were already used heavily in marketing with great practical effectiveness, it seemed painfully simple to test that in entrepreneurship. If you have well-developed theory and robust empirical models, why not test them (Krueger 1993; Krueger and Carsrud 1993)?

Since then, formal models of entrepreneurial intentions have been prolific and effective. Perhaps too effective? However, the construct of intentions appears to be deeply fundamental to human decision making and, as such, it should afford us multiple fruitful opportunities to explore the connections between intent and a vast array of other theories and models that relate to decision making under risk and uncertainty. Better still, we have reason to believe that studying entrepreneurs yields findings that speak to a far wider array of human phenomena.

2.2 Where Do Intentions “Come From”?

We have long accepted the conventional wisdom that intentions are the consequence of a process that was reasonably well understood by social and cognitive psychology. That is, we typically model intentions of any kind as having a parsimonious, powerful set of predictors that yield significant relationships with remarkable robustness (e.g., Kim and Hunter 1993).

However, looking closely at entrepreneurial intentions has started to surface some inconsistent pieces of evidence that suggest we may need to re-conceptualize intentions at a more fundamental level. However, the reader will see that this only widens the door to a broad array of interesting and useful questions.

Intentions as Phlogiston? Phlogiston was a theorized element or compound that successfully explained one quirk of oxidation processes. When something oxidized (rusted, burned, etc.) it gained weight. Thus it was proposed that phlogiston was released by oxidization. Since oxidized materials gain weight, phlogiston must have negative weight, as odd as it may seem today.

We poke fun at what is now the obvious absurdity of phlogiston, especially given our current knowledge of oxygen. However, the phlogiston model did accurately explain and predict the consequences of oxidation. The numbers worked. When we learned of oxygen and its role in oxidization, we re-conceptualized the model. Instead of subtracting phlogiston, we add oxygen. Is there any lesson here for social sciences? For intentions? It certainly argues that we need to take a long look at how we conceptualize, model, and measure entrepreneurial intentions. The numbers may work, but is there a better model?

We conceive of intentions as the consequence of obvious antecedents. However, significant correlations or beta weights need not reflect a specific direction of causality. What if the “arrows” between intent and its “antecedents” are bi-directional? What if our intentions models are capturing a static snapshot of a significantly dynamic process? Studying entrepreneurial intentions has begun to raise these very questions (e.g., Brannback et al. 2006; Krueger et al. 2007). A review of the literature suggests that very few successful studies demonstrate that changes in the antecedents of intent actually led to changes in intent. There are zero studies showing that for entrepreneurial intentions. That might even suggest the possibility that even if the causation is reciprocal, what if intent influences its “antecedents” than vice versa?

The logical conclusion is that this review should return to first principles and carefully deconstruct (and re-construct) intentions. We will begin at the beginning and look at a brief history of our models of human intent and of entrepreneurial intentions in general. From there, we will look at how intentions fit into the bigger entrepreneurial picture. We will bring in evidence from other domains that should help us with this quest, especially some striking evidence out of neuroscience. That will suggest a significant number of interesting new questions and of old questions in a new light (such as measuring intentions). From there, we will lay out an ambitious research agenda that explores our new insights into entrepreneurial intentionality and how intentions fit into the bigger picture.

2.3 Where Have We Been?

2.3.1 Philosophical and Theoretical Grounding

The notion of intentions and intentionality dates back to at least Socrates (who wondered why humans might intend evil or stupid behavior). There has always been some degree of belief that intentionality exists at the core of human agency. Husserl defined intentionality as “the fundamental property of consciousness.”

Intentional = Planned? Though later philosophers chipped away at that bold assertion, there has long been a sense that human behavior was either stimulus–response (behavior is essentially automatic in reaction to a specific signal or set of signals) or planned, where there are reasonably conscious cognitive processes at work. In fact, one recurring theme across most of the literature on intentions is that all planned behavior is intentional. (Even what appears to be stimulus–response can be the result of habituation or other conditioning. That is, it was planned behavior repeated often enough to become automatic.) Glibly equating planfulness and intent is most convenient for those seeking to model and measure intentions but, as we will see below, potentially misleading.Footnote 1

Channels and Conduits. Another recurring theme across theories and models of behavioral intentions is that intent is a resultant vector, the combination of all the various drivers each with differing direction and magnitude. We add up all the various antecedent forces and the result is intent (again, direction and magnitude).

Moreover, theory, especially empirical study, has tended to find a parsimonious list of critical antecedents for intentions as the reader will see below. All other influences are then channeled through the critical antecedents. For example, exogenous factors such as demographics and psychographics influence the intention to buy a product if and only if the exogenous factor affects one of more critical antecedents. Again, this enhances the parsimony of the model specified but hinges on the assumption that “antecedents” really are.

Static Models. Until recently, most theoretical and empirical models of intentions were static models of a clearly dynamic process. If intentions mirror other human cognitive process, then they are highly likely to be highly dynamic (and those dynamics will tend to be complex.) For example, even if the static model has the correct variables, how will the specification change over time?

Robustness. Despite the above, empirical research finds the various incarnations of the model to be remarkably robust to imperfect sampling frames, flawed measures, and even misspecification of the model (Ajzen 1987). Meta-analyses (Kim and Hunter 1993) show that the model explains considerable variance in intent (and intent explains considerable variance in behavior).

There is potentially a significant downside to this robustness, however. For example, the good news may be that we can conceptualize and measure intentions very narrowly and specifically or conceptualize and measure very broadly. However, that is also the bad news in that our “intentions” research may focus on significantly different phenomena.

Here we choose to begin with a definition of intermediate specificity. “Entrepreneurial” intentions refer to the intent to start a business, to launch a new venture. It is important to select a level of specificity where heterogeneous samples will have adequately similar mental models of what the referent means (e.g., Ajzen 1987). “I intend to start a business” need not match exactly with “I intend to be an entrepreneur” but the bulk of the empirical research to date appears to use this and we will use that as a starting point.

2.3.2 Social Psychological Grounding

Building Testable Models. Historically, Martin Fishbein developed the first widely accepted model that simply argued we should be able to consistently identify critical human attitudes or beliefs that would predict future behavior. That critical belief he dubbed “attitude toward the act” and is typically operationalized much as valence is operationalized under expectancy theory. However, he soon noticed that the attitude–behavior link was fully mediated by intentions and that adding intentions dramatically increased explanatory and predictive power.

Fishbein and his protégé, then colleague Icek Ajzen further refined the attitude–intention–behavior model by adding a more contextual influence, that of social norms. That is, other people also have a powerful impact on our decisions. The resulting theory of reasoned action (TRA) includes a measure of “perceived social norms” that elicits the perceived supportiveness of important others weighted by our motivation to comply with their wishes (Ajzen and Fishbein 1980).

Icek Ajzen then took yet another step and identified a third critical antecedent that corresponded to instrumentality in the expectancy framework, perceived behavioral control. This third iteration was called the theory of planned behavior (TPB). PBC simply measures the perception that the target behavior is within the decision maker’s control. Typically, it is proxied with a measure of perceived competence at the task such as perceived self-efficacy. Ajzen (2002) later formalized this by arguing that PBC was a combination of locus of control (this is controllable) and self-efficacy (I am capable of doing this). Moreover, Chap. 19 argues that a deeper understanding of self-efficacy and its drivers should prove particularly useful in better understanding of both intention and action subsequently. In any event, TPB remains the single most used model of human intentions to this day (Ajzen 1987, 2002) (Table 2.1).

Measurement Issues and Opportunities. The social (and cognitive) psychological approach not only led to theory-driven testable models but it also affords the opportunity to use well-tested constructs and measures. However, it also raises the need for clarity and consistency in our definitions and operationalizations. For example, if we are constantly using variables that reflect our perceptions of situations and conditions (even self-reflection) it is imperative that we fully understand the key perceptual processes that influence entrepreneurial decision making. Chapter 4 will provide the reader with much greater depth than we could do here.

Another issue that scholars often fail to fully explicate is the notion of “control,” a term that sometimes we use rather glibly.

2.3.3 A Brief History of Entrepreneurial Intentionality

Meanwhile, scholars interested in entrepreneurial behavior were obviously quite concerned with the decision that lead up to an individual starting a new venture. “Budding entrepreneur” was commonly used, though an altogether fuzzy, ill-defined term.

One of the earliest scholars to use the term, albeit indirectly, was Shapero (1982) who developed what he called the model of the “entrepreneurial event” that is conceptually similar to Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior. Shapero equated intent to the identification of a credible, personally viable opportunity. For a perceived opportunity to be credible it had to be perceived by the decision maker as desirable (TPB’s attitude and social norm) and feasible (essentially self-efficacy). He also added another antecedent, propensity to act, which captured the potential for a credible opportunity to become intent and, thus, action.

Unlike Ajzen and Fishbein’s models, however, Shapero recognized that there were forces that moderated the intent–behavior linkage. Complex goal-focused behaviors may require some sort of precipitating factor, whether the perceived presence of a facilitating factor or the removal of a perceived critical barrier. Interestingly, the Ajzen framework assumes that the target behavior is within one’s volitional control (no barriers or facilitators can intervene). Independent of Shapero, Bagozzi quickly noted this problematic facet of TPB.

Relevance to this Book: The reader would be well served to step back and review Chap. 21 on opportunity recognition. For more detailed discussion of moving intent into action, please review Chap. 23 on entrepreneurial behaviors.

Meanwhile, as social psychology rose to prominence in entrepreneurship research, so too did the notion of intentionality. In two landmark papers, Barbara Bird argued persuasively that intentionality seemed central to entrepreneurial behavior (1988, 1989). Indeed, entrepreneurs were clear exemplars of intentionality. At the same time, Jerome Katz and Bill Gartner (1988) identified intentionality as one of the four critical facets of an emerging new venture.

However, Shapero’s model had gone untested empirically, nor had the theory of planned behavior, until Krueger (1993) tested the Shapero model empirically and found very strong confirmation of the model. In turn, this suggested it might be useful for entrepreneurship scholars to turn to this literature. Krueger and Carsrud (1993) made the case that entrepreneurship really needed to take a long look at the theory of planned behavior. Simultaneously, Krueger and Brazeal (1994; Krueger 2000) further explored the applicability of the Shapero model to multiple settings (i.e., both organizational and individual entrepreneurship) by adding insights from Ajzen’s work to Shapero’s original conception. Ultimately, Krueger et al. (2000) performed a competing hypotheses test that compared Shapero’s model and TPB, finding that both models held. However, a post hoc examination suggested that adding social norms explicitly to the Shapero model increased explanatory power (see Fig. 2.1).

Other leading scholars were quick to adopt formal models of entrepreneurial intentions as well. Lars Kolvereid picked up the torch for the theory of planned behavior and quickly became the best-known user of TPB in entrepreneurship (e.g., 1996). Per Davidsson added the useful angle of exploring entrepreneurial intentions toward growth (Davidsson 1991). Today, intentions models are seemingly de rigueur, with an easy variable to measure and considerable empirical robustness. However, this explosion of studies using a formal model such as the Shapero–Krueger model or TPB or simply using entrepreneurial intentions as a stand-alone variable has raised some intriguing questions.

The first question is obviously how we are defining “entrepreneurship.” Drawing from the careers literature (e.g., Lent et al. 1994 review) the target can be conceptualized and measured narrowly or broadly but it is critical for scholars to clear about their definitions. As noted earlier, here we have chosen the broader, more inclusive definition of starting a venture while retaining the notion that intent is a cognitive state causally prior to action. However, this raises the issue that terms can easily be perceived very differently by different stakeholders in the process (see Chap. 4). Consider also the evidence in Chap. 9 that entrepreneurs, managers, students, etc., have often strikingly different maps of the entrepreneurial process. Might that have important consequences for specifying the model? (Below we will mention how cognitive style seems to affect how to specify the model.)

Another issue is whether we are looking at intentions toward entrepreneurship independent of competing alternatives. Shapero’s (1982) notion of displacement and its role in the entrepreneurial event assumes a bounded rationality perspective where some displacing event (whether push or pull) would drive a reappraisal of career options. We already know from the broader study of human intentions (e.g., Dennett 1989) that we can hold competing, even conflicting intentions. How do we effectively model that?

Moreover, as entrepreneurs take each step forward, their intent may easily change. Sarasvathy’s (2001) work shows that entrepreneurial decision making is often far from linear. Under effectuational thinking the pathway to the goal is likely to change as the entrepreneur works to find feasible and desirable paths toward a goal (which itself may well be a moving target). If entrepreneurs are effectuating we are likely to see intentions evolve in similarly nonlinear fashion. We certainly may wish to think about intentions as a stepwise process and consider modeling intentions toward each step.

Consider too the notion of bricolage (Baker and Nelson 2005). If entrepreneurs move forward with limited resources and must improvise with what they perceive as available, then what does that mean for how we model intent? For example, if the implementation of a step depends on choosing between a superior, but less controllable option and an inferior option that is seen as very controllable, it might be logical for the entrepreneur to select the seemingly inferior option.

While the model tends to hold overall, a glittering R-squared might be masking some deeper issues. Those issues already signal a need to take a long second look at how we model intentions (not just entrepreneurial intentions) and perhaps an equally long second look at the construct of intentions itself. As we peer more deeply into how we might use formal models of intentions on entrepreneurial phenomena, there are multiple opportunities to develop intellectually interesting and practically useful new insights.

2.4 Where Are We Now?

2.4.1 Chinks in the Armor? The Rise of Disconfirming Evidence

Recall that these models are predicated on the logic of a formative model, that is, there are antecedents that combine to form the target variable. One early study by Liska (1984) suggested that the “antecedents” may instead comprise a reflective model. More interestingly, Bagozzi and colleagues noticed that if we relax Ajzen’s assumption that behavior is fully volitional, that requires that we think in terms of “trying.” The seminal piece, “Trying to Consume” (Bagozzi and Warshaw 1990) forced several changes in modeling intentions effectively, especially if we are seeking to predict and not just explain.

Volition. Heckhausen (2007) frames it nicely that we too often conflate motivation (why we pursue an action) and volition (how we choose to pursue it), drawing on work as far back as Ach (1910) who demonstrated the central role of willpower as separate from motivation but mutually influencing.

The most important consideration here is that if the behavior is only partially volitional, as with goal attainment, it is inherently dynamic and must be modeled as such. A static snapshot could prove hopelessly inadequate. Second, human cognition is itself inherently complex, given the unavoidable embeddedness of even simple economic decisions in social and cultural contexts. Thus, intentions models must capture the important aspects of that. For example, we probably need to consider alternative behaviors/goals. Our intentions toward a specific career choice may not be terribly informative without looking at our intentions toward an alternative career. A third key aspect that we now need to examine is that human cognition tends to have both a rational component and an emotional component. Even the simplest “pure” economic decision has been shown to have an emotional dimension. For a classic example, witness how decision makers suddenly shift toward risk acceptance under Kahneman and Tversky’s (1979) loss frame.

2.4.2 Reciprocal Causation?

The most interesting hints about the existing models come from looking at specifying the intentions model in reverse (Krueger et al. 2007). Interestingly, early results show that the impact of intentions on the “antecedents” is stronger than the impact of antecedents on intent. Could it be that the correlations are so strong because this is a dynamic process where intent influences attitudes which influence intent, etc.? Note that the data appear to argue that the anchoring construct is intent (which in turn argues that at least our initial attitudes may be anchored on some initial intent). Note that Allport’s (1935) model treated what we call “intent” as but one of three critical antecedents of human action (cognitive, affective, and conative[intent]) that interacted in complex dynamic fashion.

Reciprocal causation goes a long way toward explaining anomalies such as the paucity of research that shows changes in attitudes leading to subsequent changes in intentions. What if we have that backward? Another anomaly this might address is that many intentions studies have found weak, even non-existent support for the influence of social norms on intent. Conceptually, social norms should be a potent predictor. However, what if social norms only influence initial intentions but attenuate as the intentions process evolves?

So, how might we begin to take advantage of these insights? (Note to the reader: Testing dynamic models can be dauntingly complex to implement properly, but we urge scholars to deploy dynamic models more often. Testing for reciprocal causation may be enlightening in many entrepreneurial phenomena.) Most important, if intentions at least partly drive subsequent attitudes, what drives initial intent? That is, what are the deeper beliefs that partially anchor intent?

2.4.3 Anchoring

If we propose that the dynamic process by which intentions evolve is anchored on some initial intent, we are still faced with the issue of understanding the origins of that initial intent. In a recent paper, Shaver (2007) called on scholars to closely examine the reasons that we attach to our intentions. That is, to what do intenders (and non-intenders?) attribute as the cause or source of their intentions? (Here I would suggest that readers interested in the key attributional processes of entrepreneurs read Chap. 17.)

Often these anchoring beliefs are very deeply held, often well outside of our mindful consideration. Kahneman and Tversky (e.g., 1979) long ago noted that human decision making often invoked an “anchor and adjust” heuristic where in novel situations we anchor our beliefs on initial information, then adjust for later information. Self-efficacy beliefs have proven to follow that dynamic (Bandura 2001; Chap. 19).

3 The Future of Entrepreneurial Intentions

3.1 The Next Generation?

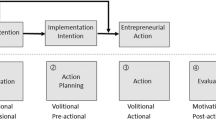

3.1.1 The Theory of Trying

However, as Fig. 2.2 suggests, Bagozzi’s theory of trying might be conceptually closest to how human actually make decisions, but the model becomes rather unwieldy in comparison to the theory of planned behavior. If a scholar finds similar levels of statistical significance in both models, the far more parsimonious TPB is an easy choice. And, despite being a static snapshot of a complex, messy dynamic process, it still offers considerable explanatory power. Nonetheless, the cutting edge remains the model depicted below (e.g., Bagozzi et al. 2003; Dholakia and Bagozzi 2002; Brannback et al. 2007).

3.1.2 Implementation Intentions

Gollwitzer and Brandstätter (1997) focused on a phenomenon that we also see in Bagozzi’s model, that of implementation intentions, following Ach’s (1910; Heckhausen 2007) work showing motivation and volition were usefully separable and allows us an immediate way to include a dynamic element. We may focus on a person’s intentions toward a goal, but once that goal is formulated there is no guarantee that the goal will be implemented. We formulate important goals all the time but really with no intent to actually implement. (Consider all the people who have an extremely strong goal intent toward smoking cessation but just a routinely fail to develop strong implementation intentions.)

The theory of trying and its variants should prove rich, fertile territory for entrepreneurship scholars (Brannback et al. 2007). At minimum, it would certainly be important for scholars to simply notice the distinction between goal intent and implementation intent: Is someone’s “entrepreneurial intention” a goal intent (they intend to begin the process) or an implementation intent (they intend to actually get the venture launched)?

3.2 The New Cutting Edges

For scholars interested in identifying even newer ground for intentions research, there are some intriguing directions to consider. We will focus on an overview of the fascinating (and useful) insights being generated by neuroscientists, and then discuss deep anchoring beliefs and implications for entrepreneurial learning and pedagogy.

3.2.1 Neuroentrepreneurship?

Consider the kind of experiment that opened this chapter. This work by Benjamin Libet dates all the way to 1983 (Libet et al. 1983) but, perhaps oddly, only now are intentions researchers fully grasping its significance. This pre-cognitive awareness is hardly an isolated phenomenon deriving from the explosively growing body of research in neuroscience.Footnote 2

To accompany neuroeconomics and neuromarketing, we now even have the research topic of neuroentrepreneurship (Stanton et al. 2008). The neuroscience perspective enables us (or forces us depending on one’s receptivity) to examine the neural and biological substrates of human decision making. As noted earlier, in the early days of entrepreneurship research we focused on surface phenomena, what we say and do. Herbert Simon famously called this the semantic layer of human cognition. Below the semantic layer was the symbolic level which holds beliefs, attitudes, and assumptions. However, below that is the neurological layer which represents the biological substrate of cognition. (Note that all cognitive activity is neural at its heart; neuroscientists seek to explore the biological underpinnings that lie beneath conscious processing.) By delving rigorously to this level we can ask some new questions and do a better job asking (and answering) existing questions of great interest.

Consider too that entrepreneurs are increasingly the focus of neuroscientists in research at Cambridge and Vanderbilt. However, these studies need involvement by entrepreneurship scholars. Focusing purely on risk taking or managing hot cognitions makes a contribution but think of the opportunities to do even more.Footnote 3

The Cambridge study (Lawrence et al. 2008) assumed that entrepreneurs need to manage emotion-laden decision making (“hot” cognition) and concluded that the neurological evidence argued that this is highly learnable. However, that skill applies to far more than entrepreneurs; entrepreneurship scholars could help narrow their focus (see Chap. 15).

The Vanderbilt study (Zald 2008) assumed that entrepreneurs are inherently risk takers and found that those high on sensation-seeking propensity have more receptors for dopamine (greater rewards for stimulating activity). Given that the entrepreneurship field has largely debunked risk taking as a predictor, how might we guide future research? What if this neurological propensity anchors individuals to prefer risky activity and if they also have a deep belief such that their mental prototype of “entrepreneur” includes “risk taker”?

Neuroscience is not just clever theory with glitzy multi-color brain images. It has practical implications too. Consider the experiment where subjects are asked to watch a video and count the number of times that a basketball is passed. In mid-video, a person in a gorilla suit walks through the screen and well over 50 % of the observers fail to notice (Simons and Chabris 1995). What does that say to educators and practitioners? We are wired to be relatively blind to change; if our attention is focused in one direction, it can be very difficult to notice something else. The marketplace is filled with “gorillas” and the entrepreneur who notices the “gorilla” reaps a competitive advantage. Or does she? If you are looking closely for the gorilla you may fail to notice the basketball passes. Where we choose to focus our intentions may be critical. We need to study this but we also need to make sure students and practitioners are aware of phenomenon such as this.

For another example, the area of the brain that processes spatial relationships tends to grow significantly larger in long-time London cab drivers (Maguire et al. 2006). Where might we see such hypertrophy in, say, serial entrepreneurs?

“My brain made me do it!”Experiments in the spirit of Libet make a persuasive case that many times, our brain generates intentions not only before we are aware of them but occasionally despite our conscious attempts to change them. Think back to Socrates’ question of why anyone would intend evil or stupid behavior. If intentions are merely the resultant vector of various unobserved neural or hormonal activities, the brain can make choices contrary to what we would develop “logically.” So where might we start looking to explore what might really be driving intentions? We return again to deep beliefs.

3.2.2 Deep Beliefs

Most human decision making occurs anyway via automatic processing. Over-simplifying a bit, we possess a large set of if–then rules to guide our behavior. Many decisions simply derive from a relatively limited set of decision rules based on an equally limited set of very deep anchoring assumptions. Only relatively few human decisions are processing mindfully and even there we might find these deep assumptions still in play. Consider the “three-year-old” technique of surfacing deep assumptions. We ask “Why do you do this?” and with each answer, you respond as a 3-year-old might with another “Why?” It may take seven or eight rounds of “Why?” before you identify the anchoring assumption, not a task we would undertake routinely.

As such it becomes very important to understand as best we can what deep assumptions lie beneath our intentions (Krueger 2007). Moreover, these assumptions also represent the critical architecture of how we structure our knowledge (including our cognitive scripts, schemas, and maps). This certainly seems to be the next frontier in entrepreneurial intentions research, if not entrepreneurial cognition in general, and we urge the reader to give significant thought to these issues.

Role Identity. Consider, for example, role identity and related constructs like 3d role demands. Our mental prototypes of “opportunity” and “entrepreneur” differ widely and are almost certainly anchored by powerful deep assumptions. These beliefs need not be functional for even experienced entrepreneurs but it is likely that novice entrepreneurs will hold beliefs that are incorrect or simply limited (Krueger 2007). Despite the effort required to surface these deep beliefs, it may be the only way to truly understand these mental prototypes that are so important (e.g., Baron 2004, 2006).

Sapir–Whorf: Deep Cultural Beliefs? Here is an example of a broad, complex research question that demonstrates the range of solid issues raised by studying entrepreneurial intentions. Can you intend to be an entrepreneur, if there is no word for “entrepreneur”? An interesting, if philosophical question that might prove extremely fascinating and of great potential utility in public policy is the one raised by the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis from anthropology. At its simplest, it asserts that if there is no word for an activity in a culture, it is very hard for members of that culture to conceptualize that activity to any significant degree. That is, it reflects a deep belief or the absence of one needed for genuine entrepreneurial activity. While we can readily envision that entrepreneurs (as we know them) have existed since the dawn of human commerce, no ancient language has a word that remotely captures our modern meaning. The modern word “entrepreneur” is itself only a few hundred years old. It might be very telling to see a linguistic analysis that compares the words used to describe entrepreneurs with economic development.

Deep Beliefs and Relevance to this Book. Most of the other chapters in this book are either critically dependent on deep beliefs or help mold them. Chapter 11 on scripts Chap. 5 on cognitive maps are two obvious places to begin thinking about deep beliefs, how they arise, and how they affect entrepreneurial decision making. These chapters in particular offer focused, detailed insights that tell us how deep beliefs can play out and how scripts and maps in turn influence how our deep beliefs can evolve.

Consider also that self-efficacy beliefs can affect mental prototypes and role identity through critical life experiences and self-efficacy can, in turn, influence how other beliefs change (Bandura 2001; Neergaard and Krueger 2005 and especially Chap. 19).

It would seem more than plausible that entrepreneurial passion reflects truly deep anchoring beliefs (Melissa Cardon, Mateja Drnovsek, Chuck Murnieks) as would entrepreneurial emotions (Isabell Welpe). The “lenses” that filter our perceptions are likely influenced greatly by deep beliefs (Evan Douglas) as would our patterns of causal attribution (Kelly Shaver), control beliefs (Erik Monsen and Diemo Urbig), other decision making processes (Veronica Gustavsson), and our processes of enacting opportunities (Connie Marie Gaglio).

However, do we not wish for prospective and current entrepreneurs to have a mindset that supports successful entrepreneurial thinking? That requires an understanding of what that mindset might comprise, whether we refer to the expert mindset discussed in Chap. 6 or we refer to “informed” intent as discussed by Hindle and Klyver.

What are the deep beliefs that consistently characterize a truly informed intent? What are the deep beliefs that underlay the cognitive scripts of expert entrepreneurs (Chap. 11)?

3.2.3 Deep Beliefs and Relevance for Teaching and Practice

However, all this is of equal, if not greater importance to educators and practitioners when we restate the issue in terms of how do we learn those assumptions? How do our deep knowledge structures arise and how do they influence (and are influenced by) entrepreneurial learning (Krueger 2009)? And consider again all the growing evidence from neuroscience that this deep “wiring” (whether innate or learned) is germane to how entrepreneurs think and act. For an entrepreneur to become fully mindful of the string human propensity toward change blindness should prove to be of significant practical value. Let us next turn to this very question.

3.2.4 Implications for Entrepreneurial Learning and Pedagogy

What we are learning has enormous potential implications for entrepreneurial education (and in some ways we see best practice in pedagogy that fits the dynamic model of intent even better than the static case). Consider Fig. 2.3 carefully. The process of learning (and ideally the process of educating) does much more than add knowledge content to the learners. The old behaviorist model of students as relatively passive vessels to be filled with information has largely given way to the constructivist model which assumes that the real objective of education is to help learners to evolve how they structure that knowledge. In short, train minds not memories.

However, it is equally important to recognize that while this process may increase their attitudes and intentions toward entrepreneurship, we must also increase them in productive directions. To inspire an ill-informed student to launch a venture borders on the negligent. Isn’t what we want to do is move learners from a mindset more like that of a novice entrepreneur toward a mindset more like that of an expert entrepreneur? We proposed the term “informed intent” for a symposium of the ICSB and as you will see from their chapter, Kevin Hindle and Kim Klyver have advanced the concept considerably. But that construct hinges on that expert mindset which is reflected in cognitive scripts (Chap. 11) and maps (Chap. 9) and those chapters will address these issues in much greater depth.

Nonetheless, it is important for the reader to know we have ample to reason to believe that (a) the expert mindset exists and (b) we can use what we know about the expert mindset to guide our teaching (e.g., Mitchell 2005; Krueger 2009) to move learners toward a truly informed intent. The constructivist model teaches us that learners’ intentions and related attitudes will change but only insofar as they reflect changes in deep anchoring beliefs (Krueger 2009). To change how we structure what we know, especially in the direction of a more informed, expert intent, the learner goes through multiple critical developmental experiences that change their deep beliefs. (Learners will thus need guidance from those who share or understand deeply the expert entrepreneurial mindset.)

Why is this important and why is this important to our discussions here about entrepreneurial intentions? It is important to emphasize the need for a more expert, informed intent. But it also speaks to the possible reality that even under reciprocal causation, intentions may drive attitudes more than the reverse. That is, the process may begin with some initial intent. To the degree that we can help anchor learners with this informed intent at the outset, learners benefit.

4 Key Future Research Directions

This chapter promised the researcher a broad, rich view of the many research opportunities offered by entrepreneurial intentions. We have thus far identified several critical areas of research: Deep beliefs, identifying critical development experiences, and formally testing Bagozzi’s theory of trying (with special attention to implementation intentions) but it may not yet be clear how these fit together.

To that end, we offer three different ways that we might profitably take a deeper look at entrepreneurial intentions:

-

(1)

Explicitly test for reciprocal causation

-

(2)

Explicitly test for contingencies

-

(3)

Explicitly test the impact of deep beliefs on “phase changes” as intentions evolve

-

(4)

Explicitly testing a “stepwise” model of how intentions evolve

4.1 Reciprocal Influence Model

Intent and Action—Dynamic Not Static Another important area that we have already begun to address is moving from static models toward different dynamic perspectives. We have already argued that we need to test models that do not assume unidirectional causality. It is highly likely that we will find reciprocal causality to be the norm, just as we find in other dynamic cognitive processes (e.g., Allport 1935). While this argues immediately for monitoring intentions and their assumed antecedents longitudinally, the discussion above argues the utility of three particular aspects. The first is that if intent is initially anchored on some deep assumptions, we need to identify those. (We discuss that below.) The second is that we need to explore the cognitive consequences such as post-decision attributions. Third, the theory of trying and the work on implementation intentions argue that we need to do a much better job of understanding perceived barriers to (and facilitators of) entrepreneurial action.

Entrepreneurial Rationalization? However, what if we confirm that intentions influence attitudes significantly more than the reverse, even with significant reciprocal causation? Recall that Shaver (2007; also his Chap. 17 here) argued that we need to include the attributional perspective, that we should identify the reasons that entrepreneurs have for their intentions. Note that beneath those surface attributions are likely deep anchoring assumptions that we need to find.

Barriers and Triggers. Another nonlinearity that the theory of planned behavior cannot directly help us with is the partial volitional control that characterizes many entrepreneurial behaviors. Shapero (1982) argued that central to the entrepreneurial event were those factors that either facilitated entrepreneurial action or offered a perceived barrier. Adding barriers to the model adds to the messiness, but isn’t it interesting that outside of Bagozzi—and entrepreneurship researchers—it is rare to see intentions research that deals overtly with barriers or facilitators (Krueger 2003)? If you realize that rigorous analysis of entrepreneurial barriers is painfully rare, the reader should be able to see fertile ground for extensive study that will add genuine value to our understanding of entrepreneurship. Consider, for example, the interaction between deep beliefs and barriers. Different motivations and different volitions might manifest itself in the barriers and ways to avoid them that entrepreneurs perceive.Footnote 4 But it also would provide genuine value to educators: Consider the diagnostic value of an instrument that rigorously assessed perceived entrepreneurial barriers.

4.2 Contingencies

Another “messiness” that has arisen of late with the intentions model is that the paths by which intentions evolve may vary systematically. For example, Krueger and Kickul (2006) found that the cognitive style index had a sizable impact on the intentions model. In fact, the model was specified differently for those scoring with an intuitive cognitive style than for analytic style. For an example from leadership studies, Anderson et al. (2006) found gender-specific construct perceptions in leadership. That is, the same scale might measure consistently different things for different people. Or do variables such as gender or cognitive style actually change the decision calculus?

But what other contingencies might yield similar results? Two strong possibilities can be found in this book. How might passion change the model? For example, Keynes argues that “animal spirits” were the real motive force behind enterprising activity (Brannback et al. 2006). Intentions when one believes that powerful others dominate your key outcomes might well differ from intentions when one has a very strong internal control belief. Also, studying entrepreneurs would permit us to see if intentions evolve differently under pure risk than under pure uncertainty.

Three other seemingly obvious contingencies remain untested. What about differences in the intentions model between necessity entrepreneurs and opportunity entrepreneurs? Should we not see meaningful differences between high and low entrepreneurial intensity? Differences in regulatory focus (promotion versus prevention) are already considered to generate different cognitive scripts (e.g., McMullen and Shepherd 2002; Baron 2004).

4.3 Deep Beliefs and Phase Change Model

Cognitive developmental psychology has long noted that human psychosocial development occurs in reasonably distinct stages connected by transition periods that are inherently experiential (Erikson 1980). In children, it is the “terrible twos” that demarcates infancy and early childhood. We see very different knowledge structures in these different stages; we also see consistent (and diagnostically useful) phenomena that characterize transition. This affords us a good sense of someone’s psychosocial development and how to help them navigate transitions. What if entrepreneurial intentions evolve similarly, exhibiting phase changes?

Phase Changes. If we plot intentions against a key attitude such as self-efficacy, we tend to see evidence that the optimal fit is not linear. It may be that noise and measurement error are amplified unpredictably, but one can also make the case that we are actually seeing one or two inflection points in the data that reflect a phase change in the evolution of entrepreneurial thinking.

That is, as entrepreneurial intentions evolve, they go through different stages. Just as entrepreneurial ventures move from ideation to nascency to launch, might not intentions follow a similar pattern, moving from one cognitive regime to another? (Consider Drnovsek’s troika of inventor, founder, and developer.) If so, we should see interesting cognitive differences between the regimes.

How do knowledge structures differ across the phases? What are the critical developmental experiences associated with each phase and with each transition? (Fig. 2.3) Such evidence would also be of invaluable diagnostic assistance to educators and to practitioners.

An Illuminating Controversy? One of my favorite controversies recently is the sizable fraction of subjects in the PSED database who are nascent and have been for years. They have not launched; they have not quit; they are still trying. Are they simply noise or do they represent something very interesting?Footnote 5 Beyond the obvious idea of applying the theory of trying to them, isn’t there a construct question here? In a world where so many people want to start a business and so many people want to believe that they are, maybe all our research has missed a very important point. Intent without the right action is not intent, it is dreaming. (Do I intend to start a business? Yes! Do I expect to start soon? Not necessarily.)

However, a nascent entrepreneur is committed (or believes she is) to a course of action. What do we gain if we identify nascency as the genuine “intending”? The careers literature distinguishes a stage prior to intent, “interest” (e.g., Lent et al. 1994). Might this also suggest a three-stage phase change model: Interest, Intent, Launch? Even if this is too limiting, this thought suggests that we may want to think long and hard about where “intent” really begins?

Deep Beliefs. However, if deep anchoring beliefs influence entrepreneurial intentions but influence differently as intentions evolve, then we might well identify different specifications for the model. Consider differences in motivation and volition (Ach 1910), Heckhausen (2007) in this simple thought experiment suggested by Elfving et al. (2008). One music entrepreneur believes “I am an entrepreneur. Therefore I start a business.” The other believes “I am passionate about music. Being an entrepreneur enables that.” One has passion for entrepreneurship, the other for music, yet both start a music business. It might be relatively straightforward to identify what lies beneath those surface beliefs. Kets de Vries (1996) argued from a psychoanalytic perspective that all humans have critical core beliefs that trigger significant action.

In any event, we would again propose that if this approach is valid, then we should see very different cognitive regimes for each phase: different scripts, schemas and maps, and different deep anchoring beliefs. Returning to our previous discussion on education and learning, we should also be able to identify the critical development experiences that correspond to different phases and especially to the transitions.

4.4 Stepwise Model

Finally, consider one additional frontier for entrepreneurship research. How many studies merely ask about starting a “business”? Instead we need to drill down into the facets of the intended business (e.g., Krueger et al. 2009). That is, consider the related notions of effectuation (Sarasvathy 2001) and bricolage (Baker and Nelson 2005).

While entrepreneurs may have a strong, well-developed intent toward launching a venture, their path may change dramatically. Even if the overall intent and attitudes need not change significantly, their intent toward the “next step” may change radically. As such, we would argue that it might be quite rewarding to monitor entrepreneurial intentions at both the overall level and for each step of their trajectory.

5 In Sum…

I began with the metaphor of the old phlogiston theory. Our existing model of entrepreneurial intentions is no phlogiston; Its underlying theory base remains strong as ever. But like oxidation, we may well find a model whose theory is even stronger and whose ability to explain, predict and to be useful to educators and practitioners is significantly better.

Studies of pre-entrepreneurial behaviors demonstrate a dizzying array of successful (and unsuccessful) patterns and sequences of activities. There simply is no single optimal path—based on behaviors. Intentions remain critical to our understanding. However, looking at entrepreneurial intentions suggests that we need to re-think how entrepreneurs arrive at their intent. That re-think will contribute to how we teach/train and how we counsel entrepreneurs.

Consider the PSED “perma-nascents” who reflect a process where applying cognitive science offers us some new clues. Who knows what else we will find? I am honored to lead off this book but every chapter in this book will be useful and provocative in this journey.

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

In North America, there are at most 2000 entrepreneurship scholars and educators, but well over 25,000 neuroscientists. The pace of research in this area will continue to explode and entrepreneurship scholars would be well served to identify ways to collaborate (e.g., Krueger and Day 2009).

- 3.

See also the nascent efforts in neuroentrepreneurship under the aegis of the Experimental Entrepreneurship (“X-Ent”) group at the Max Planck Institute of Economics in Jena, Germany.

- 4.

This “walls and holes” model surfaced in discussions at Max Planck in 2008 by volume authors Diemo Urbig, Erik Monsen, Alan Carsrud, Malin Brannback, and this author.

- 5.

This issue was raised by the book editors and gratefully acknowledged.

References

Ach N (1910) Über den Willen. Verlag von Quelle & Meyer, Leipzig

Ajzen I (1987) Attitudes, traits and actions: dispositional prediction of behavior in social psychology. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 20(1):1–63

Ajzen I (2002) Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control and the theory of planned behaviour. J Appl Soc Psychol 32(4):665–683

Ajzen I, Fishbein M (1980) Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Allport GW (1935) Attitudes. In: Murchison CM (ed) Handbook of social psychology. Clark University Press, Winchester

Anderson N, Lievens F, van Dam K, Born M (2006) A construct-driven investigation of gender differences in a leadership-role assessment center. J Appl Psychol 91:555–566

Bagozzi R, Warshaw P (1990) Trying to consume. J Consum Res 17(2):127–140

Bagozzi R, Dholakia U, Basuron S (2003) How effectful decisions get enacted: the motivating role of decision processes, desires and anticipated emotions. J Behav Dec Mak 16(4):273–295

Baker T, Nelson R (2005) Creating something from nothing: resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage. Adm Sci Q 50(3):329–366

Bandura A (2001) Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol 52:1–26

Baron RA (2004) The cognitive perspective: a valuable tool for answering entrepreneurship’s basic “why” questions. J Bus Ventur 19(2):221–239

Baron R (2006) Opportunity recognition as pattern recognition: how entrepreneurs ‘connect the dots’ to identify new business opportunities. Acad Manag Perspect 20(1):104–119

Bird B (1988) Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: the case for intentions. Acad Manage Rev 13(3):442–454

Bird B (1989) Entrepreneurial behavior. Scott Foresman and Company, Glenview

Brannback M, Carsrud AL, Krueger N, Elfving J (2006) Sex, drugs and entrepreneurial passion: an exploratory study. In: Babson entrepreneurship research conference, Bloomington

Brannback M, Carsrud AL, Krueger N, Elfving J (2007) “Trying” to be an entrepreneur. In: Babson research conference, Madrid

Bratman M (1987) Intention, plans, and practical reason. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Carsrud AL, Brannback M, Krueger N, Kickul J (2007) Family business pipelines. Academy of Management, Philadelphia

Davidsson P (1991) Continued entrepreneurship. J Bus Ventur 6(6):405–429

Dennett DC (1989) The intentional stance. MIT Press, Cambridge

Dholakia U, Bagozzi R (2002) Mustering motivation to enact decisions: how decision process characteristics influence goal realizations. J Behav Dec Mak 15:167–188

Elfving J, Brannback M, Carsrud AL, Krueger N (2008) Passionate entrepreneurial cognition: illustrations from multiple Finnish cases. Working paper under review

Erikson E (1980) Identity and the life cycle. Norton, New York

Gollwitzer P, Brandstätter V (1997) Implementation intentions and effective goal pursuit. J Pers Soc Psychol 73:186–199

Heckhausen J (2007) The motivation-volition divide. Res Hum Dev 4(3–4):163–180

Kahneman D, Tversky A (1979) Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47(2):263–292

Katz J, Gartner W (1988) Properties of emerging organizations. Acad Manage Rev 13(3):429–441

Kets de Vries M (1996) The anatomy of the entrepreneur: clinical observations. Hum Relat 49(7):853–883

Kim M, Hunter J (1993) Relationships among attitudes, intention and behaviour. Commun Res 20(3):331–364

Kolvereid L (1996) Prediction of employment status choice intentions. Entrep Theory Pract 21(1):47–57

Krueger N (1993) The impact of prior entrepreneurial exposure on perceptions of new venture feasibility and desirability. Entrep Theory Pract 18(1):521–530

Krueger N (2000) The cognitive infrastructure of opportunity emergence. Entrep Theory Pract 24(3):5–23

Krueger N (2003) Entrepreneurial resilience: real and perceived barriers to implementing entrepreneurial intentions. Paper at Babson conference, Jönköping

Krueger N (2007) What lies beneath? The experiential essence of entrepreneurial thinking. Entrep Theory Pract 31(1):123–138

Krueger N (2009) The microfoundations of entrepreneurial learning and education. In: Gatewood E, West GP (eds) The handbook of cross campus entrepreneurship. Elgar, Cheltenham

Krueger N, Brazeal D (1994) Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs. Entrep Theory Pract 18(1):5–21

Krueger N, Carsrud AL (1993) Entrepreneurial intentions: applying the theory of planned behaviour. Entrep Reg Dev 5:315–330

Krueger N, Day M (2009) What can entrepreneurship learn from neuroscience? Presentation at USASBE conference, Anaheim

Krueger N, Kickul J (2006) So you thought the intentions model was simple? Navigating the complexities and interactions of cognitive style, culture, gender, social norms, and intensity on the pathways to entrepreneurship. In: USASBE conference, Tucson

Krueger N, Welpe I (2007) Experimental entrepreneurship: a research prospectus. Working paper (also: papers.ssrn.com/abstract_id=1146745)

Krueger N, Welpe I (2008) The influence of cognitive appraisal and anticipated outcome emotions on the perception, evaluation and exploitation of social entrepreneurial opportunities. In: Babson entrepreneurship research conference, Chapel Hill

Krueger N, Reilly M, Carsrud AL (2000) Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J Bus Ventur 15:411–532

Krueger N, Brannback M, Carsrud AL (2007) Watch out, Isaac! Reciprocal causation in entrepreneurial intent. In: Australian graduate scholar exchange conference, Brisbane

Krueger N, Schulte W, Stamp J (2008) Beyond intent: antecedents of resilience and precipitating events for social entrepreneurial intentions and action. In: USASBE conference, San Antonio

Krueger N, Kickul J, Gundry L, Wilson F, Verma R (2009) Discrete choices, trade-offs and advantages: modeling social venture opportunities and intentions. In: Robinson J, Mair J, Hockerts K (eds) International perspectives on social entrepreneurship. Palgrave, London

Lawrence A, Clark L, Labuzetta JN, Sahakian B, Vyakarnum S (2008) The innovative brain. Nature 456:168–169

Lent R, Brown S, Hackett G (1994) Toward a unifying theory of career and academic interests, choice and performance. J Vocat Behav 45:79–122

Libet B, Gleason C, Wright E, Pearl D (1983) Time of conscious intention to act in relation to onset of cerebral activity: unconscious initiation of a freely voluntary act. Brain 106:623–642

Liska A (1984) A critical examination of the causal structure of the Fishbein/Ajzen attitude-behavior model. Soc Psychol Q 47(1):61–74

Maguire E, Woollett K, Spiers H (2006) London taxi drivers and bus drivers: a structural MRI and neuropsychological analysis. Hippocampus 16(17):1191–1201

McMullen J, Shepherd D (2002) Regulatory focus and entrepreneurial intention: action bias in the recognition and evaluation of opportunities. Paper presented at Babson conference

Mitchell RK (2005) Tuning up the global value creation engine: road to excellence in international entrepreneurship education. In: Katz J, Shepherd D (eds) Advances in entrepreneurship, firm emergence and growth, vol 8. JAI Press, Greenwich, pp 185–248

Neergaard H, Krueger N (2005) Still playing the game? In: RENT XIX conference, Naples

Sarasvathy S (2001) Causation and effectuation: toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Acad Manage Rev 26(2):243–263

Shapero A (1982) Social dimensions of entrepreneurship. In: Kent C, Sexton D, Vesper K (eds) The encyclopedia of entrepreneurship. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, pp 72–90

Shaver K (2007) Reasons for intent. Presentation at the international council for small business (ICSB) conference, Turku

Simons D, Chabris C (1995) Gorillas in our midst: sustained inattentional blindness for dynamic events. Br J Dev Psychol 13:113–142

Stanton A, Day M, Krueger N, Welpe I, Acs Z, Audretsch D (2008) The questions (not so) rational entrepreneurs ask: decision-making through the lens of neuroeconomics. In: Professional Development Workshop, Academy of Management Conference, Anaheim

Zald D (2008) Midbrain dopamine receptor availability is inversely associated with novelty-seeking traits in humans. J Neurosci 28(53):14372–14378

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Krueger, N.F. (2017). Entrepreneurial Intentions Are Dead: Long Live Entrepreneurial Intentions. In: Brännback, M., Carsrud, A. (eds) Revisiting the Entrepreneurial Mind. International Studies in Entrepreneurship, vol 35. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45544-0_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45544-0_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-45543-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-45544-0

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)