Abstract

This chapter discusses how gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and questioning (GLBTIQ) youth have been understood in psychology over time, providing key definitions and explaining how early understandings have developed into more recent conceptualizations and practice. Contemporary research data on GLBTIQ students in the primary and secondary years will then be presented, including statistics on experiences of bullying and mental health issues. Finally, the chapter describes the role of the school psychologist in supporting psychological health and well-being for different student groups within the GLBTIQ umbrella, and how this can be mediated against the different expectations in different Australian school contexts. A review of cultural issues for different cultural communities and parents will be provided as well as a case study, some information on training and legal issues, resources, and a quiz.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction and Definitions

This chapter discusses how gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and questioning (GLBTIQ) youth have been understood in psychology over time, providing key definitions and explaining how early understandings have developed into more recent conceptualizations and practice. Contemporary research data on GLBTIQ students in the primary and secondary years will then be presented, including statistics on experiences of bullying and mental health issues. Finally, the chapter describes the role of the school psychologist in supporting psychological health and well-being for different student groups within the GLBTIQ umbrella, and how this can be mediated against the different expectations in different Australian school contexts. A review of cultural issues for different cultural communities and parents will be provided as well as a case study, some information on training and legal issues, resources, and a quiz.

GLBTIQ youth are part of any school population whether government-run, privately-run, religious, selective or even home-schooling, elementary or secondary (GLSEN, 2012; Hillier et al., 2010). The research discussed below will show that it is safe to assume that no matter what the size of the school; there is always a probability that it contains some GLBTIQ students (and those with GLBTIQ family and friends) who could potentially benefit from school psychological services (whether or not they declare their identities or relationships at school). Both families and schools teach children from a young age that they have a sex identity (as male, female, or otherwise) related to their physical bodies—genitalia, DNA, chromosomes, and so forth (Butler, 1990). Children are often schooled into a gender identity (feminine, masculine, or otherwise) related to their clothing, mannerisms, behaviors, and social roles; and assumptions about what that means for their sexuality (in terms of whom and what they will find sexually and romantically attractive) (Jones, 2015). For GLBTIQ students, these three identity elements do not conform to either of the binary oppositional “masculine male heterosexual” or “feminine female heterosexual” identities that for much of modern history were purported as the only “psychologically healthy” identity norms.

Gay/homosexual/same-sex attracted students are those whose sexual and romantic feelings are primarily for the same sex and who identify primarily with those feelings (Jones, 2015). Both males and females can identify as gay; however, it often refers mainly to homosexual males. Lesbian students are females whose sexual and romantic feelings are primarily for other females. Research suggests around 10 % of people may be homosexual globally (Sears, 2005). Bisexuality contrastingly may count for over one-third of adolescents’ sexual experiences (Sears, 2005), and its definition is more flexible. UNESCO defined a bisexual as “A person who is sexually and emotionally attracted to people of both sexes” (UNESCO, 2012, p. 6). Other concepts have also emerged (pansexual, bicurious, mostly heterosexual) which may expand the concept (Jones & Hillier, 2014). Halperin (2009) described 13 ways of conceptualizing bisexuals, and even this extensive list ignored contemporary trends for public performances of bisexual acts by young females (Fahs, 2009). Thus, “bisexual students” includes a range of people from those largely heterosexuals who may occasionally feel or act on same-sex attraction whether publicly or otherwise, to people for whom gender does not limit their attractions, through to gender diverse students who use bisexuality interchangeably with the term “pansexual” (signifying attraction/openness to males, females, intersex transgender, and/or other gender diverse people, for example; Smith et al., 2014). Another related term is Queer, which refers to a disruptive, fluid sexuality not easily categorized (and sometimes taken up as a political resistance to categorization itself).

Transgender students fall within a broad umbrella of identities, including those who identify as a sex different to the one assigned at birth and may choose to undergo sex affirmation/reassignment surgeries; or those who simply have particularly non-conforming gender identities and/or behaviors (there is a fairly even divide between the two types amongst Australian transgender students, Smith et al.). A female to male (FtM) transgender person was labeled female or intersex (or otherwise not strictly male) at birth and may identify as male, a transman or genderqueer, for example. A male to female (MtF) transgender person was labeled male or intersex (or otherwise not strictly female) at birth and may identify as female, a transwoman or genderqueer. Gender Queer people generally do not aim to become an “opposite sex” as such but may reject traditional gender expectations altogether through their dress, hair, mannerisms, appearance, and values (del Pozo de Bolger et al., 2014; Jones & Hillier, 2013). When discussing transgender identities, one can use the term “cisgender ” as an antonym—referring to people whose sense of self matches the sex assigned at birth (Serano, 2007).

Intersex students account for around 2–4 % of the student population (OII Australia, 2012; Sears, 2005), and their difference is biologically defined. They have physical, hormonal, or genetic features that are neither wholly female nor wholly male; or a combination of female and male characteristics. Many forms of intersex exist (OII Australia, 2012—including those related to androgen insensitivities or having XXY chromosomes, for example). Intersex conditions may be diagnosed prenatally, apparent at birth, apparent at puberty or else may only be discovered when trying to conceive (OII Australia, 2012). Some intersex people identify more comfortably as male or female, some identify fluidly or changeably throughout their lifetimes. Unlike hermaphrodites (with which they are commonly confused) intersex people do not have a combination of fully functioning male and female sex organs (a feat impossible in mammals), and thus applying the term hermaphrodite is seen as offensive (OII Australia, 2012).

Historic and Current Practice in GLBTIQ Issues

Psychologists might be surprised to discover that a portion of GLBTIQ people can be quite wary of them. Their wariness, unfortunately, comes with good reason—psychology has not always been a friend to GLBTIQ people. It has, at times, been an enemy as some historic psychologists, psychiatrists, doctors, and surgeons attempted to undo GLBTIQ peoples’ differences through unwelcome and even torturous “treatments” (APA Task Force on Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation, 2009; APS, 2000). When working with GLBTIQ clients, one must have an understanding of, and be careful to contribute to overcoming, the discriminatory background of the psychological professions that unfortunately lives on in the work of a few errant individuals even to this day. GLBTIQ people have been framed differently in psychology over time, and the pathway from early understandings to more recent conceptualizations was fraught with divergent beliefs, heated debates between psychologists and street protests by the GLBTIQ community. Let us now consider historic, and then contemporary, framings for understanding GLBTIQ people.

Historic

Inver sion, GID, and Ex-gay Therapies. Variance in sexual partner desire and cross-dressing before the nineteenth century was read in relation to violation of social roles and marital ritual in European theory, rather than any specific “identity” (Foucault, 1980; Garber, 1992). By the end of the nineteenth century, both same sex desire and nonnormative gender expression was associated in a Freudian psychoanalytic frame with the psychological disorder of “inversion ”—which combined early concepts of homosexuality and role confusion, or lesbianism and penis envy (Chauncey, 1989; Freud, 1905). While Freud proposed varying talking cures and other treatments to overcome what he understood as a pathological fear of the opposite sex caused by traumatic parent–child relationships, it is notable that he identified how many inverts did not want “treatment” or believe their inversion was curable, despite religious or family pressure to change (Freud, 1910). Inverts generally became associated in psychoanalysis and sexology with aberrant sexual desire emanating from severe cross-gender identification and were cast by conservatives and traditionalists as a sign of the “ills of modern life”—a weakening of males and coarsening of females, loss of separation of gender spheres and family structures, and degeneration of the species (Halberstam, 2012). During World War I, these anxieties were furthered as women took over “male” factory jobs and domestic tasks. In schools (particularly in the USA, Australia, and the UK), there developed alongside fears over the disruption of normative gender roles a parallel concern for the seduction of students by “deviant” teachers (Sears, 2005).

Inversion became understood as in fact containing separate conditions that could exist distinct from each other: homosexuality and transgenderism. In the 1950s, the widely influential American Psychological Association’s Diagnostic and Statistics Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) —listed homosexuality as a sociopathic personality disturbance (Sears, 2005), despite evidence from researchers like Kinsey that homosexuality was indeed a common and healthy occurrence (Kinsey, Pomeroy, & Martin, 1948). Similarly, as recently as in the first few years of the 2000s the DSM IV (now outdated) still labeled transgender people with a diagnoses of “Gender Identity Disorder (GID) ” (Drescher & Byne, 2012), which described the misfit between their allocated sex and gender identity as a form of personal dysfunction within the “Paraphilias and Sexual Dysfunction ” section of the book. Through the widespread dominance of these pathologizing conceptualizations many GLBT people—including students—have been subjected to harmful but ultimately useless treatments to change their identification ranging from shock therapies, institutionalized living, right through to more modern ex-gay therapies involving public shaming or invasive changes to their dress/mannerisms and li festyles (APA Task Force on Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation, 2009).

Intersex Correctives . In the last century, a separate set of problems have been faced by intersex people at the hands of institutions. Intersex infants have widely been subjected to unnecessary and often irreversible “corrective surgery ” forced upon them in Western countries before or at school age and have typically been made to physically and socially live out their lives as males or females without their knowledge or consent, before they were old enough to understand and have a say in the matter (United Nations, 2012). These surgeries were the result of many years of institutionalized privileging of traditional male and female bodies in the medical system, doctors and surgeons mistakenly believing they were “helping” the infant by choosing their sex, and the parents of the infant being made to feel there is something “wrong” with their child such that their untreated bodily condition would be socially untenable .

Contemporary

Non-pathologizing Approach to Homosexuality

By the 1960s, an anti-psychiatry movement was forming due to the abuses experienced by GLBTIQ community members and other groups (such as women). Key researchers and gay liberation activists such as Frank Kameny worked to convince the APA that homosexuality was not only a common but healthy occurrence of same-sex attraction in humans and other animals, which did not in itself mar psychological health or happiness, nor constitute gender confusion (Spitzer, 1981). They pushed for this position using protests and negotiations with APA leadership to get invited to key meetings in the early 1970s about the DSM’s future framing of their identities (Bayer, 1987). Issues around sexual orientation were reframed as problems of personal discomfort with stigma or social rejection and were then ultimately removed from the DSM altogether. At the start of the new millennium, the APA put together a taskforce to investigate ex-gay/conversion therapies and the claim that homosexuality could be overcome through individual effort, psychological treatment, or medications. The final report not only strongly denounced ex-gay therapies, but reframed the psychologist’s role as one in support of gay, lesbian, and bisexual people expressing their identities in a fully experienced life (APA Task Force on Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation, 2009).

The Australian Psychological Society (APS) responded to this new thinking by the APA and to community advocacy efforts directly, through extensive consultation processes. In October 2000, it released its Guidelines for psychological practice with lesbian, gay and bisexual clients (APS, 2000); declaring the need for psychologists to understand that “homosexuality and bisexuality are not indicative of mental illness” (p.5). The APS further outlined its position that “social stigmatization (i.e., prejudice, discrimination, and violence) poses risks to the mental health and wellbeing of lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients” (p. 6); that LGB youth face particular risks (p. 11) and that psychologists must avoid use of methods and tests “that are biased against lesbian, gay, and bisexual people” with these clients (p. 13). The APS has steadily become far more affirming in advocacy for GLBTIQ rights—including supporting marriage rights for same-sex couples and diversity in family types in public Australian debates, for example (see http://www.psychology.org.au/community/public-interest/LGBTI/). The emphasis in school psychology has therefore strongly shifted away from any notion of “fixing” LGB students to fit heterosexual identities and towards the LGB-affirming approaches and notions of creating supportive environments now championed by t he APS (2000).

Gender Dysphoria

Modern psychology is influenced by post-structuralist feminisms from the 1980s, and Queer theory popularized in the 1990s by Judith Butler, which were much more affirming of transgender and gender queer people (Butler, 1990, 2004; Califia, 1981). These frames instead attack essentialist notions of identity, and cast gender as culturally constructed. In these perspectives, a transgender person’s gender identity is seen as no more a “performance” than anyone else’s (Butler, 1990). Transgender studies and particularly the work of Stone (1991), also influenced modern psychology by affirming transgender peoples’ right to self-definition and positive representation. There are also currently theories of transgender identities based on brain sex which understand transgender people as having had brain areas develop chemically as a sex other than the one allocated to them at birth through hormonal exposure in the womb (Pease & Pease, 2003). During the last few years, there were heated international debates between academics and activists informed by various old and new perspectives.

Drescher recounted many gender diagnosis controversies during his tenure at the DSM-5 Workgroup on Sexual and Gender Identity Disorders and the ICD-11 Working Group on the Classification of Sexual Disorders and Sexual Health (Drescher & Byne, 2012). At the time, many activists pointed to how the previous removal of homosexuality from the manual had been a positive step against homophobia in the past and were of the opinion that retaining notions of transgender issues as a psychological problem was pathologizing. Others were concerned that—unlike gay, lesbian, and bisexual people—transgender people needed “a diagnosis” to facilitate their access to medical aids if they choose to pursue transition processes. Drescher explained that ultimately the decision was made to enable transgender people to maintain access to care through maintaining the construction of gender identity as a psychological/medical issue requiring diagnosis.

However, in the DSM-5 the diagnoses was changed from Gender Identity Disorder to Gender Dysphoria—a marked and verbalized difference between the individual adult or child’s experienced gender and the gender others assign them, for at least 6 months, that causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social or other functioning. This diagnosis was no longer bundled with the Paraphilias and Sexual Dysfunction section but given its own chapter within the manual to reduce stigma. The addition of a post-transition specifier was to be used in the context of continuing treatment procedures that serve to support the new gender assignment (a kind of “exit clause” from the diagnosis, which reduces stigma, when the post-transition individual is no longer gender dysphoric but still requires access to ongoing hormone treatment).

Australian minors seeking bodily interventions (puberty blockers/surgeries) with or without parental support have historically been able to access these through the family court system by age 16 (rarer cases have been won for those as young as 11/12), but there have been recent calls within the court system to abandon this lengthy and stressful legal process (Bannerman, 2014). The emphasis on contemporary Australian school psychology for transgender students can therefore be both around supporting the individual to access experts in the field of Gender Dysphoria, to seek out an appropriate diagnosis as and if relevant, and working towards creating a network of support for the student which would ideally (but does not always) include some family members supportive of their process of self-discovery and a future that includes bodily autonomy (whether or not body affirmation or transition processes are pursued in an expression of that).

Intersex Body Autonomy

The UN now takes a clear position of protecting intersex infants against enforced medical correction (United Nations, 2012). It supports international and local intersex groups’ push for their own bodily autonomy and their right to make decisions about their gender or any surgical intervention only if they choose to later in life. The International Intersex Organisation (OII) and British Psychological Society criticized inclusion of intersex people within the Gender Dysphoria concept in the DSM-V (Kermode, 2012) because unlike transgender people, intersex people who are unhappy with their bodies may be unhappy due to surgical interventions (imposed against their will in their infancy or youth) rather than due to a desire for surgery based on their own discomfort with their gender. However, some intersex people find the concept useful in gaining access to interventions, but the emphasis in psychology should now be on supporting bodily autonomy (including access to any or no intervention; as wanted ; United Nations, 2012).

Antidiscrimination and Well-Being Reform

In 2011, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO ) held the First International Consultation on GLBTIQ issues in Educational Institutions in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (December 6–9th). The event was attended by government and nongovernment representatives and education research experts on the topic from all continents (including the first author), and they created the Rio Statement on the tenth International Human Rights Day (UNESCO, 2011). The statement asserted that the right to education must not be “curtailed by discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.” During the same period, 200 UN Member States attended the New York convening “Stop Bullying—Ending Violence and Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity.” The UN Secretary, General Ban Ki Moon, contended that bullying on these bases was “a grave violation to human rights and a public health crisis.” This framing of human rights has subsequently been supported by the United Nations as a body, with the release of the United Nation’s GLBTIQ-focused Born Free and Equal policy (United Nations, 2012). This document outlined the UN’s position in interpreting GLBTIQ rights as inherent in “human rights” for the first time, and asserted the protection of all people against discrimination (including in schools) on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity and intersex status in international human rights law. It pushed for legislative protections and violence prevention measures in all nations, and for schools to make active efforts towards inclusion to support GLBTIQ students’ psychological well-being.

Overall, contemporary psychology perspectives show a significant shift in their treatment of GLBTIQ people. The standard focus for school psychologists therefore is now more about being supportive of clients to achieve their own (varying) personal goals within a broader context of social reform and affirmation, rather than forcing students into outmoded and exclusionary frames of traditional male or female roles and identities.

Research and Statistics

The key contemporary research data on GLBTIQ students in the primary and secondary years has shifted from stigmatizing perspectives, using a combination of psychological and sociological analyses to give an account of how internal and external factors impact the students’ well-being.

Gay and Lesbian Students

The recent international literature on gay and lesbian students was mainly created by gay and lesbian education networks and (nongovernment, human rights-based) civil society organizations—USA’s Gay Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) , China’s Aibai, the UK’s Stonewall, Ireland’s BeLonG To and others (Jones, 2015; UNESCO, 2012 ). These organizations tend to focus on homophobic bullying and “school safety” for GLBTIQ students (Jones, 2015). GLSEN’s 2010 report on 7261 gay, lesbian and bisexual student participants (aged 13–21 years) stated 61 % felt unsafe at school because of their sexual orientation (Kosciw, Greytak, Diaz, & Bartkiewicz, 2010). Overall 85 % reported that they were verbally harassed (e.g., called names or threatened) at school because of their sexual orientation, and 19 % were physically assaulted (e.g., punched, kicked, injured with a weapon) because of their sexual orientation. These abuses were linked to poorer psychological well-being, including higher levels of depression and lower self-esteem. Hunt and Jensen (2009) conducted a similar survey in Great Britain (for Stonewall) exploring 1145 lesbian, gay and bisexual secondary students’ school experiences. They found 65 % of students experienced homophobic bullying in Britain’s schools, while an overwhelming majority of 97 % heard homophobic phrases at school. Only a quarter of schools explicitly taught students that “homophobia is wrong”; but at these schools same-sex attracted students were 60 % more likely not to have been bullied, 70 % more likely to feel safe, and twice as likely to feel that their school environment was supportive. Moreover, they were over twice as likely to feel able to “be themselves.”

Along with these organizations, university-based researchers—whose work is subjected to far greater and required ongoing training, ethical supervision and peer-review—have also considered GLBTIQ students and school safety. An Australian study on 3134 GLBTIQ students aged 14–21, showed a steady increase in homophobic violence in Australian schools over the past decade (Hillier et al., 2010). The study uncovered links between state and school-level education policies and significantly decreased likelihoods of violence, suicide risk and self-harm for same-sex attracted youth broadly (detailed in Jones & Hillier, 2012). Specifically, 26 % of GLBTIQ students who were aware of policy-based protection against homophobia at their own school had self-harmed, compared to 39 % whose school had no policy. Also, 13 % of GLBTIQ students who were aware of policy-based protection against homophobia had attempted suicide, compared to 22 % whose school had no policy. Further, 75 % of GLBTIQ students who were aware of policy-based protection against homophobia at school felt safe there (compared to 46 % who said their school had no policy), reflecting further data on the significantly reduced homophobic abuse in schools with policy protection—data which school psychologists are in a good position to bring the attention of school management and staff. Family support also provided further protection against negative well-being outcomes, which school psychologists can work to enhance in family sessions (but only with the student’s consent). Thus, there have been clear links made between gay and lesbian students’ well-being and the school environment, curricula and policies, and social support .

Bisexual Students

There is a new push for separate attention to bisexual students as an emerging, unique group with specific needs at school (Hepp, Kraemer, Schnyder, Miller, & Delsignore, 2005; Saewyc et al., 2009). Entrup and Firestein (2007) describe newer groups of bisexual students as part of a generation more broadly reluctant to label sexual orientation identity, more comfortable with fluidity and prone to experimentation. Girls have been identified as having higher sexual fluidity than boys—both in terms of mixed sex/bisexual attractions and changed attractions over time (Diamond, 2008; Jones & Hillier, 2014). Bisexual youth—particularly bisexual girls—have been identified in comparative studies against girls attracted to a single sex as being at higher risk of victimization, depression, diminished social connection to family and school, drug use, and suicidality (Diamond, 2008; Saewyc et al., 2009). Bisexual girls have also been highlighted for their flexibility and inclusivity in dealing with negative reactions to their identities by educating others on diversity (Crowley, 2010), traits which could be employed to help build their resilience. An Australian study revealed that bisexual students were rarely directly mentioned in education policies or interventions against homophobia at the state or school level compared to gay and lesbian students, which contrasted with the strong desire of bisexual students to have their identities reflected in school-based discussions and policies (Jones, 2015; Jones & Hillier, 2014).

Transgender Students

Most international research on gender diverse and transgender young people is primarily focused on medical and psychological interventions, risk determinants, negative pathways, suffering and social victimization (Carrera, DePalma, & Lameiras, 2012; Donatone & Rachlin, 2013; Menvielle, 2012). This focus can reinforce negative stereotypes of transgender people as living risky lives. The research also mainly focuses on adults due to difficulties in access to transgender youth (Couch et al., 2007; Jones, del Pozo de Bolger, Dunne, Lykins, & Hawkes, 2015; Jones, Gray, & Harris, 2014; Pitts, Couch, Mulcare, Croy, & Mitchell, 2009). A recent UK study explored the process of transitioning (social or medical) and how this impacts mental health (McNeil, Bailey, Ellis, Morton, & Regan, 2012). Using 889 participants across England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland aged over 18 years, their findings demonstrated that 90 % of participants had been told that transgender people were not normal and 84 % had thought of suicide, with at least 35 % attempting it. Yet once someone had medically transitioned, there were significant increases in social and mental satisfaction; findings echoed in Australian research (Jones et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2014).

A recent study in the USA examined transgender young peoples’ experience of school harassment, school strategies designed to stop harassment, and the protective role of supportive school personnel (McGuire, Anderson, Toomey, & Russell, 2010). The researchers found that transgender young people were being saddled with anti-homophobia strategies designed for lesbian, gay, and bisexual young people, which had little or nothing to do with their needs. Yet when school staff and teachers took measures to decrease or stop transphobic harassment and discrimination, transgender students were more likely to feel safe and supported, which increased levels of trust between the school and student—showing the importance of intervention by school psychologists in terms of both student and teacher training. Unfortunately, this was a rare occurrence and over 80 % of transgender participants in the survey reported they were frequently the targets of negative comments and harassment. Comparing 91 transgender students to over 3000 same-sex attracted students (aged 14–21) (Hillier et al., 2010; Jones & Hillier, 2013), Australian research uncovered that transgender students were significantly more likely to have known their diverse identity earlier; disclosed this identity to people in their social or service networks; been rejected by family; and suffered physical discriminatory abuse by peers. They were also significantly more likely to self-harm and attempt suicide. However, the transgender students were twice as likely to seek help and engage in activism (than cisgender/non-transgender same-sex attracted peers) and often displayed a sense of pride in their gender identity in the face of discrimination and adversity.

Another Australian study looked more precisely at the value of engaging in activism for this group (Smith et al., 2014), using 15 interviews and a survey of 189 transgender and gender diverse students aged 14–25. Over 66 % had seen a mental health professional in the last year, and those with supportive parents had greater access to this assistance (which 60 % of those who had accessed it found useful). A range of activities helped them feel better about themselves including listening to music (90 %), talking to friends and peers (77 %) and engaging in activism (62 %)—whether the latter involved something as private as liking an activist Facebook page or as public as giving a speech. Regardless of the outcome of their activism (in impacting their rights), engaging in it had positive impacts on increasing their well-being and social connectivity. Another factor that improved well-being for the majority of participants was engaging in gender affirmation or transition, whether socially (through their dress, role, treatment, and others’ use of their preferred pronouns) or medically (through use of puberty blockers, hormonal or surgical programs). However, it is worth noting that not all transgender students want to transition in a traditional way; some are happy to simply affirm their identity socially or to themselves. A final key finding was that 61 % of transgender students had sexual orientations not defined by gender such as pansexual, queer, and other terms—these students displayed complex thinking that challenged the models of bipolarized gender on which sexual identities are commonly constructed. The studies emphasized the need for specific school interventions for transgender students involving the individuals in determining the support they required (such as developing management plans around their access to gender experts, their desired uniform and way of being addressed) .

Intersex Students

Natural intersex bodies are mostly healthy, and it is only in a few rare diagnoses that immediate medical attention is needed from birth. For this reason, most surgeries an intersex person was subjected to during their infancy have stemmed from medical professionals trying to appease parental stress or reduce the stigma the child might face (United Nations, 2012). This is insufficient reason for such invasive intervention and can cause long-term problems for intersex people. Some intersex people may experience Gender Dysphoria over the disruption to their natural identity caused by enforced surgeries, or feel the interventions limited or obscured their identity or experiences (OII Australia, 2012). It is important for school psychologists to support intersex people to, like anyone else, have autonomy over any changes made to their bodies, and to understand their right to body acceptance and enjoyment. Therapy can provide a space for the intersex student to come to accept any physical differences they may have, work through confusion about their gender identity (if any is apparent), or issues related to any enforced surgeries if relevant.

There may be a need for family counselling which the school psychologist may be able to support themselves or offer referrals for, particularly if there has been disagreement about the child’s preferences or expressions of self. It is important to support parents to understand that their child must take charge over any decision-making processes about their bodies and identities; parents do not have a “right” of interference. This can be easier to understand if the psychologist can provide the right resources and connections to intersex communities. Intersex students may wish to maintain their privacy about their bodies and/or identities during their schooling, and it is essential to ensure this during and after any therapy. For some students, their condition may be more obvious and they may need structural support around issues of privacy and discrimination.

Role of the School Psychologist

One of the primary functions of the school psychologist is the promotion, development, and support of wellness (National Association of School Psychologists, 2006). Student social skill competencies and mental health are enhanced through the delivery of school-based services with the goal of improving outcomes for all students, including those who are GLBTIQ. By working directly with students, families, and educators, school psychologists create safe learning environments that foster healthy development (Lasser & Tharinger, 2003). Those GLBTIQ students who are experiencing difficulties may need the assistance of school psychologists to address-specific concerns (e.g., isolation, harassment, identity development).

One way of conceptualizing school psychologists’ role in delivering such services is by addressing needs in a tiered approach (e.g., universal, targeted, and intensive) especially recommended for GLBTIQ students (Alvarez, Iranipour, Trolli, & Weston, 2013; National Association of School Psychologists, 2006). Thus, efforts to create safe and accepting school environments for all students function as primary prevention approaches at the universal level and are directed at school systems, policies, and personnel and may promote a school culture and philosophy that is accepting and supportive of GLBTIQ students. By cultivating a climate that does not tolerate discrimination (through encouraging the school’s own adoption of antidiscrimination policies, education efforts, and events), school psychologists may make some positive strides towards the prevention of negative outcomes for GLBTIQ students. Even so, some students may still demonstrate a need for psychological services. In such cases, group counselling (whether GLBTIQ-specific groups or dealing with friendship groups, for example) and/or family-school collaboration may be appropriate avenues for intervention at the targeted level. Should a student need more individualized supports, such as one-on-one counselling services, then services may be provided at the intensive level. This tiered approach emphasizes prevention and ensures that services are provided at the appropriate level of intensity to match the observed needs (Alvarez et al., 2013).

Tier I

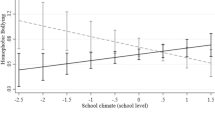

Prior to developing universal-level (Tier I) supports , school psychologists may begin with an assessment of a school’s climate for GLBTIQ students (Lasser & Tharinger, 2003). A climate assessment involves the collection of data, both qualitative and quantitative, to determine the degree to which the school environment promotes and/or inhibits the positive development of GLBTIQ students. Such an assessment may provide valuable information about students and staff attitudes towards GLBTIQ youth, levels of acceptance, recent history of harassment, and current support systems in place. This climate assessment will provide school psychologists with a baseline and help identify areas that need improvement. For example, assessment data may indicate that school events and policies are generally heterocentric (i.e., assuming that all students are heterosexual), an observation that can lead to changes at the universal level by implementing more inclusive language and practices.

School psychologists fostering a positive climate for GLBTIQ students have many resources at their disposal, many of which are included at the end of this chapter. The Gay, Lesbian, & Straight Education Network (GLSEN) provides online “toolkits” and webinars (http://glsen.org/educate/professional-development), and the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) in the USA maintains a substantial list of articles, PowerPoint presentations, position statements and policies, and other materials, many of which are available online (http://www.nasponline.org/advocacy/glbresources.aspx). School psychologists may also sponsor and/or support a “gay straight alliance” to promote inclusion (http://www.gsanetwork.org). Utilizing the information found on these sites, school psychologists may develop presentations and trainings for parents, teachers, administrators, and students, all with the goal of cultivating positive and safe learning environments for GLBTIQ students. Other school psychologist roles at Tier I include promoting the use of inclusive language and activities, implementing programs to prevent bullying and harassment of GLBTIQ students, and designating student resource offices as “safe spaces” for GLBTIQ students (Alvarez et al., 2013; Fisher, 2014).

Tier II

At the targeted level (Tier II) , the role of the school psychologist serving GLBTIQ youth turns from prevention to intervention, assisting students and their families with supports that facilitate positive and healthy adjustments and transitions. School psychologists recognize that services provided at Tier I will not meet the needs of all students and develop targeted interventions to support those with mild to moderate needs through Tier II activities such as group counselling, psychoeducational interventions, and collaborative problem solving. School psychologists may need to establish and articulate clear criteria to differentiate those students whose needs are met with Tier I supports from those who have needs that will be addressed by Tier II interventions. The focus at this level may be the promotion of well-being through support groups (Goodenow, Szalacha, & Westheimer, 2006), consultation with parents and teachers (Jeltova & Fish, 2005), family-school partnering activity (Lines, Miller, & Arthur-Stanley, 2011), and the bridging of community and school resources.

Tier III

Tier III services are reserved for those students who continue to need support after Tier II interventions have been tried with the aim of “reducing the intensity, severity, and complications relating to the presenting problem by using highly individualized and specialized interventions” (Alvarez et al., 2013, p. 26). The role of the school psychologist at this level is to provide services and supports that are tailored to the unique presenting challenges of the student in need. Fisher (2014) notes that at Tier III, the school psychologist may provide individual counselling to address concerns related to a student’s GLBTIQ status, or perhaps other issues that may be impacted by one’s GLBTIQ status, but should not assume that a student’s GLBTIQ status is central to the counselling referral. When working individually with students, the school psychologist’s role should be affirmative supportive of sexual minority youth. When appropriate, the school psychologist will often address the need to support healthy identity development and coming out, or visibility management (Lasser & Tharinger, 2003). Moreover, school psychologists are sensitive to the well-documented risk of suicide for GLBTIQ youth and should work to reduce risk through prevention and intervention.

Diverse Australian School Contexts and Policies

Australia-wide it is illegal to discriminate against GLBTIQ students in schools. New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, and South Australia have specific education policy guidelines banning homophobia and supporting education access for GLBTIQ students, and further provisions are now being pushed for in Queensland and Western Australia (Jones et al., 2014). However, there are some exemptions for religious schools at both the national and state level that may make these contexts more problematic for students wishing to express GLBT identities (no exemptions exist regarding the education access of intersex students, whose identities are regarded as primarily biological by religious bodies; Gahan & Jones, 2013). School psychologists can potentially play a major role in educating both parents and staff in very conservative environments about GLBTIQ students’ need for safety even where active support is being withheld; but there may be a need to work with external supports (such as the Australian Safe Schools Coalition) in navigating such environments in the most extreme cases. Due to the reinstatement of the National School Chaplaincy Program in Australian public schools with only religious chaplain providers in place, chaplain input on “gender issues” and student sexuality—where clarity over the confines of their roles is unclear—is possible even in otherwise secular schools; 40 % of chaplains deal with issues of student sexuality (Thielking & Stokes, 2010). While some religious school staff and chaplains are incredibly supportive, others have been linked to the promotion of homo-negative religious discourses and negative well-being outcomes for GLBTIQ students (Jones & Hillier, 2014).

Cultural Issues

Some GLBTIQ students’ school and family environments are further complicated by the intersections of different cultural perspectives. Some cultures don’t comprehend GLBTIQ identities or may see these identities as deviant, while others may acknowledge them in different forms to mainstream Australian understandings (Samoan notions of fa’fafine, males who perform the role of females for daughterless families, are an example of culturally specific gender diversity). It can be useful for school psychologists to familiarize themselves with the various perspectives in operation, and how these may best speak to each other, through consulting with local experts or online guides. Some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups may recognize Sistergirl and Brotherboy transgender identities or same-sex relations, for example, others are less supportive (these family groups are by no means uniform and have greatly varying perspectives). It is essential to foreground a student’s confidentiality and privacy where GLBTIQ status may compromise cultural/familial acceptance, and where possible, to seek out community-led GLBTIQ resources or groups (such as Sisters and Brothers NT).

Case Study

Joshua is a 15-year-old student who has been referred to Cassie Smith, the school psychologist, by his teachers due to a number of concerns. Prior to this school year, he had not experienced any significant difficulties and had, in many ways, been a model student. Well-liked by his peers and academically successful, Joshua excelled in math and science classes and played on the school’s football team. However, Joshua’s parents and teachers have noticed marked changes over the past few months and are concerned about his well-being.

Beginning in October, Joshua began to complain that he was not feeling well and stayed home from school. A visit to the doctor did not confirm any medical problems. In November, he quit the football team and became withdrawn, spending increasingly more time alone in his room. His grades began to suffer and teachers noted that he was frequently absent from class. When he was in class, he seemed inattentive, distracted, and depressed.

Following the referral for school-based psychological services made by the teacher, Joshua’s parents were contacted. They were provided information about counselling services and gave their informed consent for Joshua to see the school psychologist. At his initial consultation, Joshua appeared withdrawn and perhaps mistrustful. Ms. Smith explained that she was there to provide him with a safe and comfortable place to talk about his concerns, and assurances of privacy and confidentiality were discussed. Joshua listened and verbalized minimally at this first meeting, but agreed to return for another appointment the following week.

Over the next few sessions, Ms. Smith built greater rapport with Joshua and observed increased comfort and participation in the counselling. Sensing the timing was right, the school psychologist asked what might be the origin of the sudden declines in attendance, grades, and football playing. Initially hesitant in responding, Joshua explained that he was scared to go to school but did not elaborate. The school psychologist acknowledged his feelings and explained that it was part of her job to make sure that school is safe and comfortable for all students. Joshua then asked, “what about students who are gay?” Without asking Joshua for any additional information, Ms. Smith affirmed, “yes, my job is to make school safe and comfortable for students who are gay. In fact, I have helped several at this school and at other schools.”

At the next session, Ms. Smith mentioned to Joshua that he had asked about students who are gay the previous week. Joshua then asked for reassurances regarding confidentiality and privacy, and Ms. Smith reiterated her commitments. Joshua then disclosed that he had never before told anyone that he’s gay, but that he had known this to be true for several years. Ms. Smith thanked him for sharing this information and asked him how he felt to disclose for the first time. Joshua reported mixed feelings that included relief, anxiety, and uncertainty. Ms. Smith normalized his feelings, and also assured him that she was supportive and could help him with any concerns that he had. After the session, she noted that his coming out marked a turning point in the counselling relationship.

Over the next few sessions, Joshua explained a series of events that contributed to his current difficulties. He reported that one day he had noticed that his phone was missing and went to the locker room to find it. When he arrived he noticed that other members of the football team were looking at his phone and discovered that he had visited web sites for gay men. When he asked for his phone, the other students assaulted him verbally and physically. Since that incident, he has felt ashamed and fearful. Ms. Smith provided Joshua her unconditional support, emphasized the inappropriateness of the other students’ behaviors, and emphasized her commitment to helping Joshua. Though still anxious and fearful, Joshua reported that he felt less shame and was happy to have Ms. Smith’s assistance.

Between sessions, Ms. Smith considered ways to assist all GLBTIQ students at her school. She knew that Joshua wasn’t the only sexual minority student and that the school-wide climate needed to improve to end the kind of bullying and victimization that Joshua experienced. She was also aware that she would need administrative support to address these concerns, so she scheduled a meeting with the school’s principal. At this meeting, she planned to propose a review of the school’s policies related to nondiscrimination, bullying, and equal treatment (while balancing Joshua’s concern for privacy by not singling him out specifically when explaining the need for the review).

Over the next few counselling sessions, Ms. Smith and Joshua discussed GLBTIQ identity development, coming out issues, and visibility management. As Joshua gained more trust and confidence, he became receptive to the idea of joining a GLBTIQ support group facilitated by Ms. Smith. The support group had been developed with great sensitivity to students’ needs for privacy and confidentiality, with consideration given to time, location, and promotion to minimize participants’ anxiety over the possibility of inadvertent outing and bullying. Though Joshua was not comfortable coming out to his family, he was interested in discussing this with Ms. Smith.

Questions for the Reader

-

1.

In what ways do you think Ms. Smith was most helpful to Joshua?

-

2.

If you were in Ms. Smith’s role, what would you have done differently?

-

3.

Suppose Ms. Smith had no prior training or experience in working with GLBTIQ students. How would she best serve Joshua?

-

4.

If Ms. Smith’s principal were not supportive of her efforts to improve the climate for GLBTIQ students, how could she respond?

Ethics and Training

The International School Psychology Association (ISPA) states in its code of ethics that school psychologists acknowledge differences “associated with age, gender, gender identity, race, ethnicity, culture, national origin, religion, sexual orientation, disability, language, or socioeconomic status” (2011, p. 2). Moreover, ISPA states that school psychologists “do not engage in discriminatory procedures or practices based on” the categories listed above (p. 2). With such a strong ethical imperative to acknowledge, support, and promote fairness for GLBTIQ individuals, it follows that school psychologists have an obligation to provide training that addresses professional relationships, responsibilities, competencies, and practices (Bahr, Brish, & Croteau, 2000). However, graduate training in school psychology often falls short (Hillier et al., 2010). This may be addressed by integrating content in graduate coursework and by working to provide graduate students with field-based experiences (e.g., practicum internship) working with GLBTIQ individuals. Failure to do so may be damaging, wrongly suggesting these issues are marginal to school psychology or are too controversial to address.

Graduate programs that prepare future school psychologists should develop and publish clear affirming policies that advocate for nondiscrimination and promote justice and fairness for all. The Australian Psychology Accreditation Council (APAC) requires all university psychology programs to teach professional ethics, and all registered psychologists are legally bound by the Code of Ethics (APS, 2007)—including any appended guidelines (e.g., APS, 2000)—under the Australian Health Practitioners Regulation Authority (AHPRA) . The APS (2000) highlights specific ethical issues for psychologists to strive to be especially vigilant around issues of confidentiality and privacy for these clients (p. 14), to be aware of community impacts on the therapeutic process and to understand these clients deal with special social circumstances (p. 15). School psychologists need to understand that if they behave unethically in their professional conduct towards GLBTIQ clients—including in terms of discriminatory practice—they can be reprimanded or deregistered by AHPRA.

For this reason rather than segregating GLBTIQ issues to a course or two, faculty should integrate GLBTIQ content across courses as appropriate, including in counselling, consultation, and assessment classes. Faculty may also collaborate with field-based practicum sites to ensure that graduate students have opportunities for supervised practice in this area. Practicing school psychologists may offer trainings to parents, teachers, and administrators to facilitate the development of safe and affirming school environments for GLBTIQ students. Such trainings communicate to the school community that though often invisible, GLBTIQ students exist and have a fundamental right to thrive like all other students. Workshops for staff allow opportunities to correct misinformation and answer questions about GLBTIQ students. An educated school community is more likely to be supportive and can potentially serve as a protective factor for students at risk.

School psychologists can contribute to their own personal and professional development by exploring their personal values and ideas around working with GLBTIQ students. Reflections on how your own sexual identity influences how you respond to student–clients presenting with such issues, how confident you are in providing a Tier 1 approach and actively standing up in an organization to effect change in this area are important. What would stop you, and how would you ensure that you personally are supported and empowered if faced with organizational barriers? You may look into opportunities for peer supervision or a toolkit of evidence over time to understand your development needs.

Conclusion

The histories, data, and case information presented in this chapter have offered insight into many approaches to psychology for GLBTIQ students—ranging from those well past their use-by date, through to those illustrating innovative world standard techniques. The shifts in thinking about the psychology behind GLBTIQ identities, even quite recently, offer dramatic and exciting potential to develop your work in school psychology. It is likely the future will bring further change as researchers begin to study best practice approaches in schools based on these new theoretical frames. However, given what we currently know, this chapter has emphasized the value of an awareness of social justice struggles, structural supports in schools, and a multifaceted approach to supporting GLBTIQ students.

Summary of Key Points

-

Some GLBTIQ people are wary of psychologists due to historic mistreatment.

-

GLBTIQ students (and those with GLBTIQ relatives/friends) benefit greatly from direct school-level policy protection against discrimination in schools.

-

Dealing with prejudice involves the whole school, not just the individual experiencing discrimination. A tiered approach can be most appropriate.

-

Transgender and intersex students need to be directly consulted and involved in any specific plans for management of their school experience.

Future Directions and Resources

Australia-wide and state-specific bodies can be consulted for further information, guides, posters, training, and other resources:

-

Australia-wide: Gay and Lesbian Issues and Psychology (GLIP, an APS members group), Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays, The Safe Schools Coalition Australia, and Organisation Intersex International (Australia-wide)

-

State-specific: Proud Schools (NSW), Safe Schools Coalition Victoria and Ygender (VIC), The Freedom Centre and The Equal Opportunity Commission (WA), Open Doors (QLD), ShineSA (SA), Bit Bent (ACT), Headspace and QLife (NT), Sisters and Brothers (NT), and Working it Out (TAS).

Test Yourself Quiz

-

1.

Define “intersex.”

-

2.

How does “Gender Dysphoria ” differ from “Gender Identity Disorder?”

-

3.

List some ways in which school psychologists can support GLBTIQ students’ well-being.

-

4.

What is a “tiered approach” to school psychology?

-

5.

Which GLBTIQ support bodies can you contact for your location?

References

Alvarez, Z., Iranipour, A., Trolli, C., & Weston, J. (2013). Supporting LGBTQ students in schools: A three-tiered approach. Paper presented at the National Association of School Psychologists, Seattle, WA.

APA Task Force on Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation. (2009). Report of the task force on appropriate therapeutic responses to sexual orientation. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/pi/lgbt/resources/therapeutic-response.pdf

APS. (2000). Guidelines for psychological practice with lesbian, gay and bisexual clients. Melbourne: Australian Psychological Society. Retrieved from http://www.psychology.org.au

APS. (2007). Code of ethics. Melbourne: Australian Psychological Society. Retrieved from http://www.psychology.org.au

Bahr, M. W., Brish, B. B., & Croteau, J. M. (2000). Addressing sexual orientation and professional ethics in the training of school psychologists in school and university settings. School Psychology Review, 29(1), 217–230. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.une.edu.au/docview/219644632?accountid=17227

Bannerman, M. (2014). Family Court Chief Justice calls for rethink on how High Court handles cases involving transgender children. ABC News. Retrieved November 18, 2014, from http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-11-17/chief-justice-calls-for-rethink-on-transgender-childrens-cases/5894698

Bayer, R. (1987). Homosexuality and American psychiatry. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net.ezproxy.une.edu.au/2027/heb.30507.0001.001

Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415389550.

Butler, J. (2004). Undoing gender. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415969239.

Califia, P. (1981). What is gay liberation? Heresies, 3(12), 30–34.

Carrera, M., DePalma, R., & Lameiras, M. (2012). Sex/gender identity: Moving beyond fixed and ‘natural’ categories. Journal of Sexualities, 15(8), 995–1016. doi:10.1177/1363460712459158.

Chauncey, G. (1989). Christian brotherhood or sexual perversion? Homosexual identities and the construction of sexual boundaries in the World War 1 era. In M. Duberman, M. Vicinus, & G. Chauncey (Eds.), Hidden from history: Reclaiming gay and lesbian past. New York: Meridian. ISBN 0453006892.

Couch, M., Pitts, M., Muclcare, H., Croy, S., Mitchell, A., & Patel, S. (2007). Tranznation: A report on the health and wellbeing of transgendered people in Australia and New Zealand. Melbourne: Australian Research Centre in Sex Health and Society. ISBN 1921377242.

Crowley, M. S. (2010). How r u??? Lesbian and bi-identified youth on MySpace. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 14(1), 52–60. doi:10.1080/10894160903058881.

del Pozo de Bolger, A., Jones, T., Dunstan, D., & Lykins, A. (2014). Australian trans men: Development, sexuality, and mental health. Australian Psychologist, 49(6), 395–402. doi:10.1111/ap.12094.

Diamond, L. M. (2008). Sexual fluidity: Understanding women’s love and desire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674026247.

Donatone, B., & Rachlin, K. (2013). An intake template for transgender, transsexual, genderqueer, gender nonconforming, and gender variant college students seeking mental health services. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 27(3), 200–211. doi:10.1080/87568225.2013.798221.

Drescher, J., & Byne, W. (2012). Gender dysphoric/gender variant (GD/GV) children and adolescents: Summarizing what we know and what we have yet to learn. Journal of Homosexuality, 59(3), 501–510. doi:10.1080/00918369.2012.653317.

Entrup, L., & Firestein, B. A. (2007). Developmental and spiritual issues of young people and bisexuals of the next generation. In B. A. Firestein (Ed.), Becoming visible: Counseling bisexuals across the lifespan (pp. 89–107). New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231137249.

Fahs, B. (2009). Compulsory bisexuality? The challenges of modern sexual fluidity. Journal of Bisexuality, 9(3), 431–449. doi:10.1080/15299710903316661.

Fisher, E. S. (2014). Best practices in supporting students who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning. In P. Harrison & A. Thomas (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology (pp. 191–203). Bethesda, MD: NASP.

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge. New York: Pantheon. ISBN 9780394739540.

Freud, S. (1905). Three essays on the theory of sexuality (J. Strachey, Trans. 1961 ed.). London: Penguin. ISBN-13 978-1614270539.

Freud, S. (1910). The psychology of love (Vol. 2006, S. Whiteside, Trans.). London: Penguin. ISBN-13 978-0142437469.

Gahan, L., & Jones, T. (2013). From clashes to coexistence. In L. Gahan, & T. Jones (Eds.), Heaven bent: Australian lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex experiences of faith, religion and spirituality (pp. xxi–xxviii). Melbourne: Clouds of Magellan. ISBN 978-17-429-8354-7.

Garber, M. (1992). Vested interests: Cross-dressing and cultural anxiety. New York/London: Routledge. ISSN 0039-3827.

GLSEN. (2012). READY, SET, RESPECT! GLSEN’s elementary school toolkit. New York: Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network. Retrieved from http://glsen.org/readysetrespect

Goodenow, C., Szalacha, L., & Westheimer, K. (2006). School support groups, other school factors, and the safety of sexual minority adolescents. Psychology in the Schools, 43(5), 573–589. doi:10.1002/pits.20173.

Halberstam, J. (2012). Boys will be… Bois? Or, transgender feminism and forgetful fish. In D. Richardson, J. McLaughlin, & M. E. Casey (Eds.), Intersections between feminist and queer theory (pp. 97–115). New York: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 9781403945310.

Halperin, D. M. (2009). Thirteen ways of looking at a bisexual. Journal of Bisexuality, 9(3), 451–455. doi:10.1080/15299710903316679.

Hepp, U., Kraemer, B., Schnyder, U., Miller, N., & Delsignore, A. (2005). Psychiatric comorbidity in gender identity disorder. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58, 259–261. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.08.010.

Hillier, L., Jones, T., Monagle, M., Overton, N., Gahan, L., Blackman, J., & Mitchell, A. (2010). Writing themselves in 3: The third national study on the sexual health and wellbeing of same-sex attracted and gender questioning young people. Melbourne: Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society. ISBN 9781921377921.

Hunt, R., & Jensen, J. (2009). The school report: The experiences of young gay people in Britain’s schools. London: Stonewall. Retrieved from http://www.stonewall.org.uk/educationforall

International School Psychology Association. (2011). Code of ethics. Retrieved from http://www.ispaweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/The_ISPA_Code_of_Ethics_2011.pdf

Jeltova, I., & Fish, M. C. (2005). Creating school environments responsive to gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender families: Traditional and systemic approaches for consultation. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 16, 17–33. Retrieved from http://isites.harvard.edu/fs/docs/icb.topic47789.files/Creating_School_Environments_Responsive_to_GLBT_Youth.pdf

Jones, T. (2015). Policy and gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender and intersex students. New York: Springer. ISBN 9783319119908.

Jones, T., del Pozo de Bolger, A., Dunne, T., Lykins, A., & Hawkes, G. (2015). Female-to-male (FtM) transgender people’s experiences in Australia. Dordrecht: Springer. ISBN 9783319138282.

Jones, T., Gray, E., & Harris, A. (2014). GLBTIQ teachers in Australian education policy: Protections, suspicions, and restrictions. Sex Education: Sexuality, Society and Learning, 14(3), 338–353. doi:10.1080/14681811.2014.901908.

Jones, T., & Hillier, L. (2012). Sexuality education school policy for GLBTIQ students. Sex Education, 12(4), 437–454. doi:10.1080/14681811.2012.677211.

Jones, T., & Hillier, L. (2013). Comparing trans-spectrum and same-sex attracted youth: Increased risks, increased activisms. LGBT Youth, 10(4), 287–307. doi:10.1080/19361653.2013.825197.

Jones, T., & Hillier, L. (2014). The erasure of bisexual students in Australian education policy and practice. Journal of Bisexuality, 14(1), 53–74. doi:10.1080/15299716.2014.872465.

Kermode, J. (2012). Debate surrounds intersex inclusion in the DSM V. Pink News. Retrieved June 13, 2012, from http://www.pinknews.co.uk/2012/06/13/debate-surrounds-intersex-inclusion-in-the-dsm-v/

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. R., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual behaviour in the human male. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders. ISBN 0253334128.

Kosciw, J., Greytak, E. A., Diaz, E. M., & Bartkiewicz, M. J. (2010). The 2009 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth in our nation’s schools. New York: Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network. Retrieved from http://www.glsen.org/binary-data/GLSEN_ATTACHMENTS/file/000/001/1675-5.PDF

Lasser, J., & Tharinger, D. (2003). Visibility management in school and beyond: A qualitative study of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. Journal of Adolescence, 26, 234–244. doi:10.1016/S0140-1971(02)00132-X.

Lines, C., Miller, G. E., & Arthur-Stanley, A. (2011). The Power of Family-School Partnering (FSP): A practical guide for school mental health professionals and educators. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415801485.

McGuire, J., Anderson, C., Toomey, R., & Russell, S. T. (2010). School climate for transgender youth: A mixed method investigation of student experiences and school responses. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(10), 1175–1188. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9540-7.

McNeil, J., Bailey, L., Ellis, S., Morton, J., & Regan, M. (2012). Trans Mental Health Study 2012. Retrieved from http://www.scottishtrans.org/our-work/research/

Menvielle, E. (2012). A comprehensive program for children with gender variant behaviours and gender identity disorders. Journal of Homosexuality, 59(3), 357–368. doi:10.1080/00918369.2012.653305.

National Association of School Psychologists. (2006). School psychology: A blueprint for training and practice III. Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists.

OII Australia. (2012). Intersex for allies. Melbourne: OII Australia. Retrieved form https://oii.org.au/21336/intersex-for-allies/

Pease, B., & Pease, A. (2003). Why men don’t listen and women can’t read maps. London: Orion Publishing Group. ISBN 0767918177.

Pitts, M., Couch, M., Mulcare, H., Croy, S., & Mitchell, A. (2009). Transgender people in Australia and New Zealand: Health, wellbeing and access to health services. Feminism and Psychology, 19(4), 475–495. doi:10.1177/0959353509342771.

Saewyc, E., Homma, Y., Skay, C., Bearinger, L., Resnick, M. D., & Reis, E. (2009). Protective factors in the lives of bisexual adolescents in North America. American Journal of Public Health, 99(1), 110–117. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.123109.

Sears, J. T. (2005). Youth, education and sexualities: An international encyclopedia (Vol. 1: A–J). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313327483.

Serano, J. (2007). Whipping girl: A transsexual woman on sexism and the scapegoating of femininity. Emeryville, CA: Seal Press. ISBN 9781580051545.

Smith, E., Jones, T., Ward, R., Dixon, J., Mitchell, A., & Hillier, L. (2014). From blues to rainbows: The mental health and well-being of gender diverse and transgender young people in Australia. Melbourne: Australian Research Centre in Sex Health and Society. ISBN 9781921915628.

Spitzer, R. L. (1981). The diagnostic status of homosexuality in DSM-III: A reformulation of the issues. American Journal of Psychiatry, 138(2), 210–215. ISSN 0002-953X.

Stone, S. (1991). The empire strikes back: A posttranssexual manifesto. In J. Epstein & K. Straub (Eds.), Body guards: The cultural politics of gender ambiguity (pp. 280–304). New York: Routledge. ISSN 10489487.

Thielking, M., & Stokes, D. (2010). Submission to the consultation process for the National School Chaplaincy Program. Melbourne: The Australian Psychological Society Ltd. Retrieved from http://www.psychology.org.au/Assets/Files/APS-Submission-School-Chaplains-July2010.pdf

UNESCO. (2011). Rio statement on homophobic bullying and education for all. Rio de Janiero, Brazil: UNESCO. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/new/en/hiv-and-aids/our-priorities-in-hiv/gender-equality/anti-bullying/

UNESCO. (2012). Education sector responses to homophobic bullying. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. ISBN 9789230010676.

United Nations. (2012). Born free and equal: Sexual orientation and gender identity in international human rights law. New York/Geneva: United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. Retrieved from http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/BornFreeAndEqualLowRes.pdf

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Glossary

- Heteronormativity

-

Producing or reinforcing heterosexuality as a “naturalized” and normative structure.

- Homophobia

-

An individual’s or society’s misunderstanding, fear, ignorance of, or prejudice against gay, lesbian, and/or bisexual people.

- Intersex

-

Having physical, hormonal or genetic features that are neither wholly female nor wholly male; or a combination of female and male.

- Gender Dysphoria

-

A medical diagnosis related to transgender people in the DSM-V, referring to extreme discontent with the sex allocated to an individual at birth.

- Gender Identity Disorder/GID

-

A medical diagnosis for transgender people used in the DSM-IV and since replaced with the less stigmatizing gender dysphoria.

- Lesbian

-

Women whose sexual and romantic feelings are primarily for other women and who identify with those feelings.

- Pansexual or Omnisexual

-

People whose sexual and romantic feelings are for all genders; this rejects the gender binary of male/female and asserts that there are more than two genders or gender identities. Inclusive terms considering the gender diverse.

- Puberty Blockers

-

Non-testosterone-based hormone treatment (GnRH agonists) used to suspend the advance of sex steroid induced and thus block pubertal changes (and secondary sex characteristics) from occurring/developing further for a period of time.

- Queer

-

Queer is an umbrella term used to refer to the LGBT community, and also inconsistent gender or sexual identities.

- Sex

-

A complex relationship of genetic, hormonal, morphological, biochemical, and anatomical differences that impact body and brain. Some people are intersexed and do not fit easily into a dimorphic division of two sexes that are ‘opposite’.

- Sexual Orientation

-

The direction of one’s sexual and romantic attractions and interests towards members of the same, opposite or both sexes, or all genders.

- Transphobia

-

An individual’s or society’s misunderstanding, fear, ignorance of, or prejudice against transgender people.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Jones, T., Lasser, J. (2017). School Psychological Practice with Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex, and Questioning (GLBTIQ) Students. In: Thielking, M., Terjesen, M. (eds) Handbook of Australian School Psychology. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45166-4_30

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45166-4_30

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-45164-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-45166-4

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)