Abstract

This chapter explores social learning theories and communities of practice through the contextual lens of barriers to adopting online education, specifically within the design field of landscape architecture. Social learning theory is present in a several ways. First, it informs the underlying research approach, a consensus-building activity known as Delphi study. The chapter explores social aspects of learning and the formation of learning communities. Finally, social learning theories provide a mechanism to mitigate faculty concerns and facilitate the creation of an online collaborative learning and design space. Subsequently, by examining meaningful application, our understanding of learning is enriched and expanded.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

While online education has become prevalent in higher education as universities seek to expand their reach, invest in technological innovation, and restructure budgetary systems, it has remained largely nascent in the design fields of architecture, landscape architecture, and interior design (Bender & Good, 2003; Christensen & Eyring, 2011; Yuan & Powell, 2013). This is despite the widespread adoption of innovations in communication technologies that support social learning environments and the creation of online learning communities (García-Peñalvo, Conde, Alier, & Casany, 2011; Hew & Cheung, 2013). The emergent nature of online education in the design fields is especially perplexing considering the nearly two decades of research on virtual design studios (VDS) .

Previous research has identified many of the affordances and constraints of online design education , or distributed design education (DDE) , and indicated that DDE can be an effective method for both design instruction and collaboration (Bender & Vredevoogd, 2006; Ham & Schnable, 2011; Kvan, 2001). DDE provides many affordances that are particularly compelling to design education, such as facilitating the sharing of design work, easily preserving and cataloging design iterations, and enabling access to geographically diverse faculty, students, and practitioners (Dave & Danahy, 2000; Ham & Schnable, 2011; Park, 2011). In light of the successful precedents and identified affordances, we hypothesized that the slow growth of DDE stemmed not from pedagogical or technological shortcomings, but from faculty apprehension to adopt DDE.

This chapter describes the results of a national Delphi study on the barriers to the adoption of DDE by landscape architecture faculty. The results of the study reveal that managing the social aspects of the learning environment and the creation of a community of practice are the most prominent barriers to the adoption of DDE. The application of social learning theories, combined with a knowledge of the function of communities of practice, provides an opportunity to develop pedagogical strategies to mitigate for many faculty concerns.

Background

The Culture of Design Education and the Studio

While the studio has served as the foundation of design education for nearly two centuries, it was not until the 1980s that the learning processes occurring within the studio were theorized by Donald Schön (Webster, 2009). Schön proposed a theory of design learning called reflective practice, the process whereby a designer constantly analyzes the problem, process, and their own actions in order to develop an optimal design solution (Schön, 1983, 1985). Schön described this process as a conversation between the designer and the design, implying an iterative process not entirely controlled by the designer that results in moments of struggle and serendipity (Schön, 1985).

The complexity and ambiguity of the design process is what precipitates the master–learner relationship in studio pedagogy. On its face, good design may seem easy to achieve; yet a student quickly learns that the process is difficult to master. Schön (1983) emphasizes the need for the master to tutor the student by describing the paradox of the design studio: the student cannot know what needs to be done to design successfully, yet the student can only learn what needs to be done by designing. This can create a frustratingly circular learning situation in which the student must muddle through the process, learning in fits and starts by trial, error, and exploration; and a setting in which the careful guidance of a master to provide instruction and modeling is highly valued.

The master–student relationship is supplemented by interactions with other students in the studio. As an open learning community, students are able to view and learn from each other, especially their more advanced peers. In some extreme cases studios even merge learners studying similar topics irrespective of their level of development or skill—committing to vertical mentoring through peers (Barnes, 1993). Through the combination of mentoring provided by the studio master and other students, individual students become enculturated into the design process, and in so doing they enter the community of designers.

Theorization of the Design Studio Environment

While curriculum and focus have undergone significant changes over the last two centuries, the physical design studio (PDS) remains the fundamental instructional environment in design education and its basic pedagogical tenants have remained relatively constant (Bender, 2005; Broadfoot & Bennett, 2003). These tenants include a space where with ample opportunities for instruction and modeling from a master and more advanced peers, and where students can freely observe and collaborate with their peers. The studio is meant to be a rich, social-based learning environment in which students must confront the complexities of realistic design situations and, by so doing, advance their understanding and skills.

While Schön (1985) described and theorized the process of design , a deeper understanding of design studio pedagogy and the interactions that occur within the studio can be developed through the application of the social learning theories of legitimate peripheral participation, distributed cognition, and affinity spaces. The purpose of the studio and the nature of the master–learner relationship of the physical design studio (PDS) can best be theorized by legitimate peripheral participation theory (LPP) . The social characteristics of the studio environment by the theories of distributed cognition (DC) and affinity spaces (AfS) , in which students are exposed to authentic design activities in a cognitive apprenticeship under the guidance of a studio master in an open environment in which students are free to observe, learn, and collaborate with each other (Black, 2008; Gee, 2004; Hutchins, 1995; Lave & Wenger, 1991; Schön, 1985).

The master–learner relationship of the studio is meant to provide students with the opportunity to shadow the actions of a mentor within the design community of practice. However, Lave and Wenger (1991) noted that successful cognitive apprenticeships involved more than the structural establishment of a master–learner duality. The master must provide the learner with contextual and social opportunities for legitimate peripheral participation in the community of practice. In theory, the master–student relationship in design education is meant to function in this manner, with the instructor playing the role of a wise master who provides the student with careful instruction and projects intended to replicate practice (Hokanson, 2012; Schön, 1985)

Much of the design process can be segmented into a series of rational design decisions and, as a result, the social structure of the studio increasingly resembles the collaborative learning environment Hutchins (1995) describes in distributed cognition theory, that is, a rational, replicable approach to design, where the process is separated into discrete tasks. This means that more advanced students are better able to act as tutors to less advanced students as they master each task. As in Hutchins (1995) description of naval crewmen learning from those above them and tutoring those below them, in the design studio there is an expectation that upperclassmen learn from the studio master while simultaneously providing instruction and modeling to lower classmen. It has been recognized that successful tutoring in the studio space is incumbent upon an open layout, a spatial arrangement supported by Hutchins (1995) horizon of observation, which can be distilled to the basic concept that a person is able to learn from what they can physically observe in the environment around them (George & Bussiere, 2015).

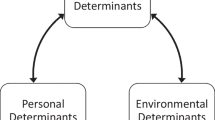

As a student masters each task they assume a new role as a teacher and are then able to act in the role of a teacher to help tutor other students. This shifting of social learning roles within the studio, based on knowledge and competencies, is described in AfS theory, wherein a fluid social structure enables members of the learning community to simultaneously maintain an identity as a master and learner, dependent upon the discrete activity being performed. Thus, the social hierarchy of the studio may be envisioned as static only at the top (between the studio master and the students) and then the students engage in a fluid social hierarchy based on their individual competencies in design or other technical tasks (see Fig. 4.1) (Black, 2008; Gee, 2004).

Research in Distributed Design Education

Beginning in 1995, there was considerable interest generated by the exploration and development of early DDE techniques in the form of the virtual design studio (VDS) (Broadfoot & Bennett, 2003; Dale, 2006; Maher, Bilda, & Gül, 2006; Sagun, Demirkan, & Goktepe, 2001). These early experiments were typically built around a short design project—few appeared to have much longevity beyond their initial use—and they are best viewed as forward-thinking explorations of the use of technology for both design and collaboration.

These early descriptions focus most of their commentary on the technological tools being utilized, a trend that has since continued in most of the disseminated work on DDE, and the majority of articles detailing the use of a VDS do not consider or emphasize the social and pedagogical implications of a VDS (Bender & Good, 2003; Budd, Vanka, & Runton, 1999; Maher & Simoff, 1999; Maher, Simoff, & Cicognani, 1996; Simoff & Maher, 1997). There are notable exceptions to this focus on the novel use of technology for collaboration. For example, Cheng (1998) explored the potential of DDE to mimic and improve upon the social relationships that exist in a PDS, and explicitly discussed the unique challenges of establishing authentic social identities and relationships in a VDS. Kvan (2001) is an early example, and one of only a handful, who addresses the fact that the use of a VDS precipitates a reevaluation of the accepted design studio pedagogy because it dramatically alters the environment in which learning occurs.

Researchers repeatedly discuss the benefits of the VDS to design education, especially noting the ability of DDE to provide students with access to geographically dispersed individuals, enabling collaboration with other students, educators, practitioners, critics, and clients that would not have been possible in a PDS (Dave & Danahy, 2000; Kvan, 2001; Levine & Wake, 2000). DDE offers the ability to expose students to foreign cultures and practices, potentially altering the way they perceive and think about design and social values (Kvan, 2001; Sagun et al., 2001). Utilizing a VDS can increase time flexibility and efficiency in teaching, enabling higher contact rates between the student and instructor and more time spent in deeper discussion about topics (Brown, Hardaker, & Higgett, 2000; Kvan, 2001; Li & Murphy, 2004; Shannon, 2002). Researchers also suggest that DDE could enable a greater emphasis and understanding of the design process through the preservation and efficient organization of data related to the iterative development of a student’s design (Brown et al., 2000; Matthews & Weigand, 2001; Sagun et al., 2001; Schnable, Kvan, Kruiff, & Donath, 2001).

Despite the identified benefits of DDE, its use remains rare in landscape architecture programs. A review of studio pedagogy reveals that the social relationships that exist in a studio are critical to facilitating learning and, while most DDE research has focused on the technical aspects of DDE, we speculated that the ill-defined social component of DDE is of most concern to faculty and a great impediment to its adoption. One of the primary purposes of this chapter is to explore the extent to which faculty acknowledge the challenge of including a social component in DDE and the extent to which social learning theory might be a meaningful lens to address that challenge.

Methodology

A Delphi study was used to develop consensus on the critical barriers to the adoption of DDE from a panel of experts composed of landscape architecture faculty members employed at accredited landscape architecture programs in the USA (Hasson, Keeney, & McKenna, 2000; So & Bonk, 2010). Delphi studies as a consensus building activity are fundamentally aligned with social learning theory. In addition, they are designed to incorporate a heterogeneous pool of participants that represent the full range of opinions in a field. In this particular case we included faculty members who had presented in the Design Teaching and Pedagogy track at the Council of Educators in Landscape Architecture Conference within the previous 3 years, as well as department heads. Forty-three individuals agreed to participate.

The potential barriers were drawn from an extensive literature review that identified the constraints and barriers to the adoption of DDE. A thematic-synthesis was used to produce a list of 22 potential barriers to adoption. Following the development of the barriers, the first round of the Delphi study was carried out. During this first round, panelists had the opportunity to suggest other barriers, and two additional barriers were added to subsequent rounds. Panelists used a 7-point Likert scale to evaluate the importance of each potential barrier. Panelists were also asked to justify their selections by providing written feedback.

At the commencement of the second and third rounds, panelists received the mean and standard deviation of the entire panel’s responses on each barrier, as well as their own response from the previous round. They were also provided with the anonymous comments provided by the panel. In light of this additional knowledge, panelists were asked to reconsider each barrier and either change or maintain their response, again being asked to justify their position. The rounds continued until distribution stability (expressed as a percentage change in total scale units) was reached for the individual barriers (Scheibe, Skutsch, & Schofer, 1975). Twenty-three of the 24 barriers achieved stability after the third round and, with diminishing participation rates, the Delphi was ended after the third round.

Results

The final rank order of the barriers was developed from the mean score of the panel’s responses for each barrier. In instances of ties, the rank order was determined first by the mode, and then the IQR (see Table 4.1). Graphing the mean scores revealed a series of natural breaks which were used to divided the barriers into four categories: critical, important, less important, and not important. Barriers in the critical category had an average mean score of 5.07, those in the important category had an average mean of 4.59, those in the less important category had an average mean of 4.16, and the average mean of the not important category was 3.51. The critical barriers also had the highest level of consensus, with an average SD of 1.26, and only one barrier having an IQR of higher than 1.

The results show that the critical barriers to faculty adoption of DDE are issues related to social interaction (barriers 1, 4–7), issues with financial compensation (barrier 2), and a lack of confidence in the medium (barrier 3). While the first barrier is concerned with the overarching concept of online education, the panelist comments related to this barrier imply that the undergirding concern is social. Combined with the fourth through seventh barriers, it is clear that faculty are preeminently concerned about preserving the social characteristics of traditional studio culture. Mitigating for these barriers will require a nuanced effort from educators and researchers to create a pedagogy that emulates the social learning environment of the studio. Educational theories concerned with the social role of learning and the formation of communities of practice will provide an ideal foundation on which to construct such a pedagogy (Black, 2008; Gee, 2004; Hutchins, 1995).

Discussion

With the critical barriers to adoption identified, we turn to an analysis of how we might use the identified social learning theories to mitigate for these barriers while preserving the essence of the studio. Here we discuss the social component of the individual critical barriers, excluding the second and third barriers, which are not tied to pedagogy or the social learning environment of the studio.

Critical Barrier 1: Instructors Believe the Studio Method Cannot Be Replicated Using DDE

The panel’s comments made it clear there is concern about the loss of physical interaction as a means of conveying and converging on information and design ideas. Several comments refer to an intangible quality of the studio, a “something” that is not replicable outside of the physical confines of the studio. These comments are best summarized by a panelist’s response: “There is something lost when students can’t look across to other’s desks and see their works and/or iterations, overhear conversations, or participate in impromptu pop-up discussions and topics.” While it is impossible to define what that something is specifically, from other comments it can be inferred that it refers to the social learning environment that is created within the studio. Comments suggest that students would be unable to interact with each other, and therefore learn from each other through observation and impromptu learning sessions.

There is also a belief that an online education platform that could support all of the communication and design tools necessary simply does not yet exist. Panelists acknowledge that learning goals might be achieved, but believe that design results would be substantially different. There is discussion about the ability of technology to facilitate many of the types of in situ communication that occurs in the studio, but that elements of the learning process are either lost or degraded: “I think that it could be done technically and logistically, but I think that the process and the experience would lose something important.”

While the PDS provides students an immediate horizon of observation composed of their proximate peers, research has shown that DDE can provide students with the ability to expand their horizon of observation. However, it appears that the panel is more concerned about the time factor of the horizon. In the studio, students are able to immediately see and interact with their peers, while in many VDSs it is possible to see peer’s work, but it is often cumbersome or requires many steps to do so. A possible DDE solution would be to create a social sharing network that is integrated with a file sharing service such, in which digital files that are updated on a student’s computer are automatically updated for quick browsing in the VDS. As a social network, this service would accommodate the sharing of more than simply files, enabling students to easily comment on each other’s work and provide tutoring on specific tasks.

Critical Barrier 4: Building Rapport with Others Is Difficult

The most common theme is concern about the ability of existent technological tools to support the rich forms of communication necessary for building rapport. Although panelists discuss many common forms of computer-mediated communication and social media, they express the view that “there is a disconnect between [people]” when using these technologies, and that they are unable to develop the “deeper and more meaningful connections” that can be made face-to-face. There is also concern about if students would learn to communicate with their future clients and the public. One panelist sums up this concern: “What I worry about is if they will continue to be able to design for REAL PEOPLE. Especially if they don’t get outside and away from their electronic devices long enough.”

Countering this technology gap theme is discussion on the nature of how modern students collaborate. Some panelists feel that students are digital natives, and that they find it as easy (some suggest easier) to communicate and build rapport in an online setting as in a face-to-face setting. One panelist describes building rapport online as being the “preferred method” of modern students and, with the heavy involvement students have in social media, it is possible that “rapport of this kind has come into its own in education.”

Between the two sides of this debate, some panelists felt that building rapport is no more or less difficult online as it is face-to-face, and that building good rapport in a face-to-face environment is not a foregone conclusion. These panelists suggest building rapport is dependent upon the characteristics of the individual students and how effectively the scaffolding in the course encourages communication.

Pedagogically, the instructor should introduce course activities that provide scaffolding for rapport building in a DDE course that may not have been necessary in a F2F course. Hutchins (1995) concluded that groups collaborate best when there are social dependencies built into the collaborative tasks. The nature of the task should require rapport building in order to be successful. Returning to the social learning network suggested above, this network could also be made to include practitioners or community members in order to gather feedback and enable students to experience legitimate peripheral participation with the community of practice they are training to enter. In this way, students would be able to build rapport amongst themselves, as well as taking additional steps towards the center of the community of practice.

Critical Barrier 5: Students Feel Socially Isolated from Their Peers

Within this barrier, the most commonly discussed topic by the panel revolves around modern students and how they socialize. In the first two rounds, comments were dismissive of this barrier, stating that “students don’t care” about being isolated and that the large majority of modern students regularly communicate and socialize online via social media. However, by the third round many panelists insisted that students should not be isolated, and that some of the most important learning that happens in the studio happens organically between peers, and that students in a DDE environment are not be able to enjoy a similar type of social experience.

In the third round, another theme emerged focusing on the social interactions of the studio environment, but these comments focused on the development of broader social skills. “Students need to learn to interact with their peers” and “effective social interaction and communication is critical” for designers. These comments took a more global look at the issues of isolation and communication, criticizing computer-mediated discussions as insufficient to teach the social skills required in the landscape architecture profession. However, using the same rationale, a similar argument can be made that students need to be able to master and communicate via new media and technologies, as these become increasingly prominent in practice and broader society (Boyd & Ellison, 2007; Vanderkaay, 2010).

Concerns stemming from this barrier are best understood in the context of the physical environment of the studio, where students are free to observe and interact with their peers. Social isolation is worse than simply reducing the amount of social exchanges between students, it represents the reduction in the quantity of ideas that are shared, and, by extension, the quality of designs that are subsequently produced (Dutton, 1987; Schön, 1983).

As theorized by Hutchins (1995) , it is critical that learners are able to observe each other, especially their more advanced peers, in order to facilitate learning and mastery of more advanced skills. Conversely Lave and Wenger (1991) demonstrated that depriving learners of the ability to observe their more advanced peers decreased learning performance. In the studio this observation often takes the form of socialization between students as they move between each other’s desks to talk about their designs and other topics.

It is our belief that preventing social isolation in DDE will once again need to rely on social dependencies being built into learning tasks. Requiring basic interaction (á la making discussion posts or participating in chat group) is not sufficient because the social aspect remains either undeveloped or tertiary to the task. Social interactions need to be scaffolded in such a way that they advance the task.

While a concern, DDE can provide an opportunity to reduce the social isolation for some individuals. Because of the power structure of the studio, the studio master holds an inordinate amount of power by virtue of their position. This has led some to note that the student is often kept in a position of subservience in which they do little more than mime and try to please the studio master; a social structure that prevents them from participating in meaningful exploration and keeps them intellectually isolated (Anthony, 1991; Dutton, 1987; Webster, 2009). Online education has been shown to encourage participation from the most socially vulnerable students because it can flatten the power structure of the studio (Matthews & Weigand, 2001). Affinity spaces demonstrate that this is the case, in that otherwise socially isolated students are able to share their specific expertise without having to open themselves for criticism on other aspects of their knowledge (Black, 2008).

Critical Barrier 6: Lack of Face-to-Face Interaction

The panel was most concerned about constraints that technology places on the communication process. While some panelists acknowledge that verbal and nonverbal communication can be facilitated online, they are concerned about the “limitations of technology to replicate all of the factors involved in communication.” These limitations impact how students communicate, and therefore what type of culture they form amongst themselves. Panelists also believe that the studio environment is invaluable for providing an embodied experience that “replicates real world situations of design practice.”

They recognize that “DDE could facilitate effective communication but may be [sic] not the same type of communication that happens [in the studio].” Out of this there was a discussion of the pros and cons of any potential changes, such as impacts to the time it takes to communicate, the ability to include more stakeholders in the communication process, and the ability to record and revisit conversations later. However, the suggestion is that even though physical face-to-face communication is preferable, not having it is not insurmountable. It is likely this barrier will become less of a concern as technology improves and students have the ability to communicate in a manner ever-closer to F2F interactions.

Critical Barrier 7: Critiquing Student Work Is Difficult

In the initial round, the major concern was related to the technical constraints of technology in facilitating critiques. Panelists worried that what is already “a difficult process in a face-to-face environment” would become more difficult in a distributed one, and that oftentimes “technology complicates simple communication.” The concern appears to be not that technology is unable to facilitate a critique, but rather that it would become more difficult to do so.

The panel also expressed concern about the ability to effectively convey emotion during a critique in DDE. Critiquing students “is always a dicey proposition fraught with risks when students have fragile egos, insecurities, and lack emotional resilience.” They wonder if the process will become more difficult if there is no adequate way to express “voice inflection, facial expressions, and other non-verbal techniques to communicate feedback” in a considerate manner.

The comments of the panel, especially those that focus on the emotional state and reaction of the students, suggest to us that faculty are focusing too much on the social relationship itself during a critique, and not attributing a large enough role to the actual design product. During the critique, the student’s work acts as an open tool. An open tool is a device that is available to multiple individuals to utilize, and can be used to encourage or constrain interaction and learning between individuals (Hutchins, 1995). The student’s design provides a shared context and mechanism by which the master can teach, and the student can learn (Anthony, 1991; Hokanson, 2012).

In regards to critiques, DDE pedagogy should emphasize the design itself and, in this particular instance, de-emphasize the social relationship. We propose that more emphasis should be placed on group critiques where one-on-one social interactions are less prominent and the power structure is more balanced, theoretically helping to emphasize the design itself. Additionally, emphasis should be placed on facilitating interaction between students, and the critiques that occur between students as they review each other’s work. Emphasizing inter-student critiques is supported by all of the social learning theories we have cited in this chapter, and is supported by design experience (Dutton, 1987).

Conclusion

In this chapter we describe how design studio pedagogy is based on social relationships, and how it can be theorized using the social learning theories of legitimate peripheral participation, distributed cognition, and affinity spaces. We suggest that distributed design education has not seen widespread adoption largely because of faculty concern over the medium’s ability to facilitate rich social interactions of the type that occur within the PDS. The results of the Delphi study support this position, as five of the seven critical barriers referenced social issues.

In analyzing the barriers, we propose that a VDS needed to be built around social relationships, potentially using a platform akin to modern social media networks. Such a platform can enable students to have an expansive horizon of observation and near-immediate access to the work of their peers, receive tutoring from their peers, and potentially enable peripheral participation in the design community of practice through engaging practitioners. Pedagogically, tasks assigned to students need to have social dependencies built in which require students to build social connections in order to be successful. Critiques should focus on utilizing the design as an open tool, preferably through the use of group critiques that reduce the social difficulties that can occur between student and master in a critique. We believe that through the application of these social learning theories to DDE pedagogy, it is possible to create a robust social learning environment that supports most of the social framework of the design studio.

References

Anthony, K. H. (1991). Design juries on trial: The renaissance of the design studio. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Barnes, J. (1993). A case for the vertical studio. Journal of Interior Design, 19(1), 34–38.

Bender, D. M. (2005). Developing a collaborative multidisciplinary online design course. The Journal of Educators Online, 2(2), 1–12.

Bender, D. M., & Good, L. (2003). Interior design faculty intentions to adopt distance education. Journal of Interior Design, 29(1 and 2), 66–80.

Bender, D. M., & Vredevoogd, J. D. (2006). Using online education technologies to support studio instruction. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 9(4), 114–122.

Black, R. W. (2008). Adolescents and online fan fiction. New York: Peter Lang.

Boyd, D. M., & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1), 210–230.

Broadfoot, O., & Bennett, R. (2003). Design studios: Online? Comparing traditional face-to-face Design Studio education with modern internet-based design studios (pp. 1–13). Presented at the Apple University Consortium.

Brown, S., Hardaker, C. H. M., & Higgett, N. P. (2000). Designs on the web: A case study of online learning for design students. Association for Learning Technology Journal, 8(1), 30–40.

Budd, J., Vanka, S., & Runton, A. (1999). The ID-Online Asynchronous Learning Network: A “Virtual Studio” for interdisciplinary design collaboration. Digital Creativity, 10(4), 205–214.

Cheng, N. Y.-W. (1998). Digital identity in the virtual design studio. In Proceedings of the 86th Associated Collegiate Schools of Architecture’s (ACSA) (pp. 1–13). Cleveland, OH.

Christensen, C., & Eyring, H. J. (2011). The innovative university: Changing the DNA of higher education. New York, NY: John Wiley.

Dale, J. S. (2006). A technology-based online design curriculum. In TCC (pp. 2–11). Retrieved from http://www.researchgate.net/publication/228611136_A_technology-based_online_design_curriculum.

Dave, B., & Danahy, J. (2000). Virtual study abroad and exchange studio. Automation in Construction, 9, 57–71.

Dutton, T. A. (1987). Design and studio pedagogy. Journal of Architectural Education, 41(1), 16–25.

García-Peñalvo, F., Conde, M., Alier, M., & Casany, M. (2011). Opening learning management systems to personal learning environments. Journal of Universal Computer Science, 17(9), 1222–1240.

Gee, J. (2004). Situated language and learning: A critique of traditional schooling. New York, NY: Routledge.

George, B. & Bussiere, S. (2015). Factors impacting students’ decisions to stay or leave the design studio: A national study. Landscape Research Record, 3, 11–21.

Ham, J. J., & Schnable, M. A. (2011). Web 2.0 virtual design studio: Social networking as facilitator of design education. Architectural Science Review, 54(2), 108–116.

Hasson, F., Keeney, S., & McKenna, H. (2000). Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32(4), 1008–1015.

Hew, K., & Cheung, W. S. (2013). Use of Web 2.0 technologies in K-12 and higher education: The search for evidence-based practice. Educational Research Review, 9, 47–64.

Hokanson, B. (2012). The design critique as a model for distributed learning. In L. Moller & J. B. Huett (Eds.), The next generation of distance education (pp. 71–83). Boston, MA: Springer US.

Hutchins, E. (1995). Cognition in the wild. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kvan, T. (2001). The pedagogy of virtual design studios. Automation in Construction, 10, 345–353.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning and legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Levine, S. L., & Wake, W. K. (2000). Hybrid teaching: Design studios in virtual space. In Proceedings of the National Conference on Liberal Arts and the Education of Artists (Vol. 1). New York City, NY.

Li, M.-H., & Murphy, M. D. (2004). Assessing the effect of supplemental web-based learning in two landscape construction courses. Landscape Review, 9(1), 157–161.

Maher, M. L., Bilda, Z., & Gül, L. F. (2006). Impact of collaborative virtual environments on design behavior. In Proceedings of Design Computing and Cognition '06. Netherlands: Springer.

Maher, M. L., & Simoff, S. (1999). Variations on the virtual design studio. In Proceedings of Fourth International Workshop on CSCW in Design. Compiègne, France.

Maher, M. L., Simoff, S., & Cicognani, A. (1996). The potential and current limitations in a virtual design studio. Sydney, Australia: Key Centre of Design Computing, Department of Architecture and Design Science. Retrieved from http://web.arch.usyd.edu.au/~mary/VDSjournal/.

Matthews, D., & Weigand, J. (2001). Collaborative design using the internet: A case study. Journal of Interior Design, 27(1), 45–53.

Park, J. Y. (2011). Design education online: Learning delivery and evaluation. The International Journal of Art & Design Education, 30(2), 176–187.

Sagun, A., Demirkan, H., & Goktepe, M. (2001). A framework for the design studio in web-based education. The International Journal of Art & Design Education, 20(3), 332–342.

Scheibe, M., Skutsch, M., & Schofer, J. (1975). Experiments in Delphi methodology. In H. A. Linstone & M. Turoff (Eds.), The Delphi method: Techniques and applications (pp. 257–281). London, England: Addison-Wesley.

Schnable, M. A., Kvan, T., Kruiff, E., & Donath, D. (2001). The first virtual environment design studio. In Proceedings of the 19th Conference on Education in Computer Aided Architectural Design in Europe. Helsinki, Finland.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

Schön, D. A. (1985). The design studio: An exploration of its traditions and potentials. London, England: Royal Institute of British Architects.

Shannon, S. J. (2002). Authentic digital design learning. In Proceedings of the 36th Conference of the Australian and New Zealand Architectural Science Association (pp. 461–468). Geelong, Australia.

Simoff, S., & Maher, M. L. (1997). Design education via web-based virtual environments. In Proceedings of the Fourth Congress of Computing in Civil Engineering. New York, NY: ASCE.

So, H.-J., & Bonk, C. J. (2010). Examining the roles of blended learning approaches in computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) environments: A Delphi study. Educational Technology & Society, 13(3), 189–200.

Vanderkaay, S. (2010). The social media evolution. Canadian Architect, 4(10), 39–40.

Webster, H. (2009). Architectural education after Schön: Cracks, blurs, boundaries and beyond. Journal for Education in the Built Environment, 3(2), 63–74.

Yuan, L., & Powell, S. (2013). MOOCs and open education: Implications for higher education. Bolton, UK: Center for Educational Technology and Interoperability Standards.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

George, B.H., Walker, A. (2017). Social Learning in a Distributed Environment: Lessons Learned from Online Design Education. In: Orey, M., Branch, R. (eds) Educational Media and Technology Yearbook. Educational Media and Technology Yearbook, vol 40. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45001-8_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45001-8_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-45000-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-45001-8

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)