Abstract

The empirical theory of democracy, contrasting the “classical” conception, is often said to have been conceived by Schumpeter (1962). Since then, a lot of theoretical and empirical contributes have been added. Most of them are directly related to the approach proposed by the venerable founding father. For this reason, they form the so-called economic theories of politics, strongly based on assumptions of individuals as rational and self-interested decision-makers (Downs 1957; Riker and Ordeshook 1973; Olson 1965). Another strand of research developed since the 1960s’ agreeing to completely different theoretical underpinnings. Here the main concepts draw from sociology, political culture being (one of) the most important (Dahl 1971; Lijphart 1968).

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

The empirical theory of democracy, contrasting the “classical” conception, is often said to have been conceived by Schumpeter (1942). Since then, a lot of theoretical and empirical contributes have been added. Most of them are directly related to the approach proposed by the venerable founding father. For this reason, they form the so-called economic theories of politics, strongly based on assumptions of individuals as rational and self-interested decision-makers (Downs 1957; Riker and Ordeshook 1973; Olson 1965). Another strand of research developed since the 1960s’ agreeing to completely different theoretical underpinnings. Here the main concepts draw from sociology, political culture being (one of) the most important (Dahl 1971; Lijphart 1968).

The merits and shortcomings of both economic and sociological approaches have been discussed in Barry (1978), and they are not worth to be recalled here. Rather, it deserves attention the fact that both approaches share a point of view: in opposition with the “ancient democracy” (Finley 1985), contemporary democratic regimes are essentially representative (Manin 1997). This point of view drives the researchers’ consideration towards the usual paraphernalia of representation: electoral systems (Gallagher and Mitchell 2008; Cox 1997), parties and party systems (Sartori 1976; Katz and Crotty 2005), and parliaments (Fish and Kronig 2009).

Therefore, within the studies that address democracy (but also different kinds of regimes), direct democracy has been a neglected issue for a long time. However, scholars have recently become more interested in it. For instance, Lijphart (2012, chapter 12) deals with referendum as a tool requested to change rigid constitutions, and hence exploited by institutional engineering to reinforce the consensual working of proportional democracies. Significantly enough, the examination of referenda by Lijphart is confined in a short “addendum”, while the process of constitutional change is mainly referred to the judicial review wielded by special courts. Even Tsebelis (2002) deals somewhat incidentally with the role of referenda. In his theoretical stand, referenda add a veto player to the decisional process of a given polity, namely the median voter of the electorate expressing its point of view through a referendum.

More recently, Aghion et al. (2004) provided a theory of constitutional design that focuses on the optimal degree of insulation of political leaders, which is the trade-off between the stability that allows the government to implement its policy, and the risk of expropriation on citizens that a powerful government may cause. Within this framework we argue that direct democracy institutions signal a non-insulation of political leaders to empirically evaluate some of the circumstances that in the model explain the degree of insulation (i.e., make direct democracy institutions more or less likely), and some others that have been proposed in the political science literature to describe the extent of the democracy. Specifically, we investigate the impact of these elements on a unique dataset consisting of a country index on citizen lawmaking in 87 countries. This index refers both to the availability of direct democracy instruments and to their actual use.

The paper proceeds as follows: in Sect. 2, we posit the theoretical hypotheses to explain the adoption of direct democracy. In Sect. 3, we present the methodology behind the Direct Democracy Index, the indicator we use to measure direct democracy. Section 4 describes the data and specifies the variables used for the empirical analysis. We then present the results in Sect. 5. Section 6 offers some concluding remarks.

2 Direct Democracy: Looking for Explanations

Empirical literature discussing the impact of economic, political and cultural factors on the extent of direct democracy is not developed, probably due to the lack of a formalized theory that explicitly refers to this issue.Footnote 1 Starting from de Tocqueville (1835), political theorists have debated the requisites for successful democratic institutions. Building on them, Aghion et al. (2004) have recently considered a problem of constitutional design in which a society has to choose the degree of insulation of its political leader, namely the degree to which a ruler is maintained accountable by citizenship. The idea is that if, once elected, a leader cannot be limited by ex post checks and balances, society runs the risk of a tyranny of the majority, or alternatively, of a tyranny of a dictator. The model focuses on this tradeoff between delegation of power and ex post controls of policy makers.Footnote 2 This framework is used to empirically discuss the determinants of the degree of insulation. They consider two sets of explanatory variables, political institutions and ethno-linguistic fractionalization. Autocrats are more insulated than democratically elected governments. Within democracy, presidential systems are the “most insulated” form of government, while hybrid regimes—such as semi-presidentialism—and parliamentary systems are the least insulated. Overall, the authors find significant evidence that various indices of insulation are positively correlated with measures of ethno-linguistic fractionalization. Thus, highly fragmented (polarized) societies tend to have more “insulated” rulers (less democratic or more presidential). Footnote 3 The majority group knows that it cannot dominate the other groups unless its leader is sufficiently insulated.

In terms of the theory drawn in Aghion et al. (2004), referenda represent one of the forms of non-insulation of political rulers, the extreme form of non-insulation closest to the letter of the model being a popular referendum that requires a majority of 100 %. Our analysis builds on their theoretical framework. We focus on direct democracy institutional arrangements only, and extend the investigation to other factors that the literature analyzes as conditions for democracy. These hypotheses fall into three broad categories: economic and demographic, institutional and cultural.

Economic and Demographic Variables

Economic theory has investigated the link between democracy and growth, predicting contrasting effects (Przeworski and Limongi 1993; Przeworski et al. 2000). On the one hand, democratic institutions guarantee checks and balances, limiting the possibility that politicians will extract rents from the public budget at the expense of the voters’ welfare. On the other hand, an expansion of democracy promotes a redistribution of income from the rich to the poor and may increase the power of interest groups. Evidence that democratization leads to economic growth is quite weak.

We are interested in the reverse channel of such a link, focusing on the impact of economic variables on direct democracy institutions. The hypothesis is loosely based on Lipset (1959), who discusses a broad category of economic development as determinant of democracy, including indexes of wealth, urbanization and industrialization. The key element of this hypothesis is that richer countries are more willing to promote democratic values and more receptive to norms of tolerance.

Both La Porta et al. (1999) and Alesina et al. (2003) pinpoint ethnic fragmentation as determinant of economic success both in terms of output (GDP growth) and the quality of institutions (measured by the extent of corruption, political freedom, etc.). The results show that the democracy index they use views racial fractionalization as negatively affecting economic success. The polarization of society, as we already emphasized, is also one of the explanatory variables used in the empirical analysis provided by Aghion et al. (2004) to test the model of political insulation. Across the different estimation techniques, ethnic fractionalization seems to increase the probability of ending up in a more autocratic and insulated regime.

Institutional Variables

Political economy models (Persson and Tabellini 2003) have investigated the institutions of democratic regimes. This approach sheds light on how alternative institutional arrangements affect the binding force of checks and balances and, therefore, the accountability of the political system. A central feature of this line of research is that effective decision-making power in presidential regimes is split among different politicians, who are separately and directly accountable to voters. Presidential systems are therefore predicted to have less rent extraction than parliamentary ones. Furthermore, the electoral formula may shape rent extraction through the sensitivity of election outcomes to the incumbent’s performance. Since incumbents may be more severely punished under plurality rule than under proportional representation, the former may be more effective in deterring rent extraction.

Starting from these hypotheses, we argue that as presidentialism and majoritarian parliamentarism are more accountable to voters, blocking legislation in these systems takes place indirectly and within the institutional structure of delegation of power. Voters are less interested in using direct democracy instruments in the presidential system and under majoritarian rules. These instruments therefore work as corrective devices, substituting other institutional arrangements in securing checks and balances between the bodies of government.

Cultural Variables

The link between democracy and cultural factors has been debated in political science since Lipset (1959). Lipset predicts that a better educated population entails better chances for democracy and democratic practices. This positive relationship may exist because education can teach individuals the value of staying politically involved. Subsequent analyses have discussed the role of cultural conditions on democracy. These studies typically use religious affiliation as a proxy for the “dimension” of the culture (i.e., ethics, tolerance, trust), and evaluate democracy simply in terms of government performance. Putnam (1993) analyzes the effect of the provision of public goods, while Landes (1998) is concerned with the flow of people, goods and ideas between countries. Furthermore, many cultural explanations of democratic institutions and policies include a political element, as Landes’s emphasis on the use of intolerance for political purposes makes clear. Huntington (1991) claims that the Catholic Church in the 1960s became a powerful force for democratization, probably to maintain its membership levels. Other scholars have turned to the link between education and democracy. Matsusaka (2005) claims that the rising level of education among the population and the decrease of information costs due to the communication technology revolution have dramatically reduced the knowledge advantage that elected officials had over ordinary citizens. The result of these trends is that important policy decisions are shifting from legislatures to the people. Glaeser et al. (2004, 2007) also discuss the link between education and democracy, arguing that schooling teaches people to interact with others and increases the benefits of civic participation. Democracy has a wide potential base of support, but offers weak incentives to its defenders, whereas dictatorship provides stronger incentives to a narrower base. As education increases the benefits of civic participation, it simultaneously raises support for more democratic regimes.

3 An Index of Direct Democracy

Direct democracy is a broad term that encompasses a variety of decision-making processes. They greatly differ according to the institutional design and the political culture prevalent in each country. Measuring direct democracy is not an easy task. Scholars have pursued different solutions. For instance, Scarrow (2001) uses an index based on three dimensions—direct election of executives and head of states, constitutional referenda, legislative referenda and/or direct decision on municipal ordinances—for 23 Western countries since 1970–1999, showing a spread of direct democracy institutions for the whole period. The diffusion of direct democracy tools in 18 presidential democracies in Latin America has been documented by Breuer (2007), who claims that referenda reduce accountability. Anckar (2004) provides a typology of direct democracy in small islands and micro-states. He finds that, in comparison with other democratic countries, micro-states make limited use of the popular initiative and the policy vote, whereas they frequently apply the constitutional referenda. According to his conclusion, the colonial background explains this pattern. Recently Altman (2011) arranged a large dataset of 949 mechanisms of direct democracy in 186 countries. He finds that the use of direct democracy is positively associated with the level of democracy in general, the age of the regime, the type of colonial heritage, and the use of direct democracy in neighboring countries.

This cursory review makes clear that including all tools countries employ to implement direct democracy in a simple classification is complex. An inclusive list would include town meetings, recall elections, initiatives, and various forms of referenda.

We build a Direct Democracy Index (DDI) for the period 2000–2005 referring to initiatives and referenda as already dealt with by several authors. The right of initiative enables citizens to originate legislation, acting as agenda setters bringing together the signatures of a number of endorsers. A referendum instead is a ballot vote on a law already approved by the legislature, which must also qualify for the ballot by receiving a predetermined number of signatures. Citizens are involved in both cases, by signing initiatives or by voting on a referendum.

Our index is based on three sources: Kaufmann (2004) for 43 Western and Central-Eastern European countries, Hwang (2005) for 33 Asian countries, and Madroñal (2005) for 17 Latin American countries. This amounts to 93 cases, but due to lack of data for independent variables our dataset is restricted to 87 countries. To produce our own classification we have principally built on Kaufmann’s procedure. He sorts his 43 cases into seven categories, giving each country a specific rating. Each country is classified as: (1) radical democrat; (2) progressive; (3) cautious; (4) hesitant; (5) fearful; (6) beginner; (7) authoritarian. The sources for Asia and Latin America instead use a fourfold ranking. After a careful reading of each country report, we have re-ranked these countries according to the more sensitive Kaufmann’s seven-step scale. Finally, we have recoded the original Kaufmann’s scores by giving 7 to radical democrats—Switzerland being the only case—and 1 to authoritarianisms. The result of such a procedure is summed up in Table 1.

In implementing the DDI, we try to move from de iure circumstances that make referenda and initiatives possible. Rather, we try to rely on a de facto measure of direct democracy. This implies that we consider the procedures a political system provides in order to propose, approve, amend, and delete laws through popular initiative and referenda, as well the actual practices of direct democracy and the general political condition a country experiences. This is necessary to avoid fallacies dues to formally existing but emasculated procedures for direct democracy.

Consider the case of Belarus. A respectable amount of nine referenda has been held from 1995 to 2004. However, they were deceitfully used by President Alexander Lukashenka to increase his power at the expense of the legislature, and the wanted results have allegedly been obtained by prosecuting political oppositions and harassing the voters in front of the polling stations. Therefore, as shown in Table 1, the country has the lowest DDI score. Remarkably, Altman (2011, 93–94) provides a full list of the “nightmare team”, namely those authoritarian countries formally adopting direct democracy, but subjecting its results to the rulers’ ultimate control.

A consequence of the methods of measurement used in this field of research is that all indexes are affected by some degree of subjectivity. Yet we believe that this is not a reason to condemn them. Indeed, several measures regularly used in comparative politics are built by recurring to subjective judgments: from Left to Right positioning (Castles and Mair 1984), to the levels of freedom (see Freedom House indices), to the diffusion of corruption (see Transparency International indices).

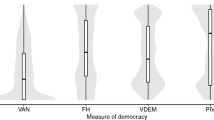

To validate our measurement of direct democracy we match the DDI just described with other measures of democracy. We thus correlate DDI scores with two of the most renowned indicators to assess democracy, the Freedom House and the Polity IV indexes for our 87 countries. In its original form, FH scores 1 for the highest and 7 the lowest level of freedom. We have rescaled these scores in such a way that 1 stands for low and 7 for high democracy, so that a positive sign is expected for all relationships. The correlations are detailed in Table 2. As expected, all relationships among the three indexes are positive. Moreover, the correlation between DDI and the Polity IV index reach a medium level, while that linking DDI with the Freedom House index is rather high. As a result, our index shows that direct democracy is related to democracy in general, an intuitive information however substantiating the procedure of measurement.

Table 3 details the relationship between direct democracy and levels of freedom as measured by the Freedom House index. Remarkably, countries with a poor level of direct democracy (scores 1–2 on the DDI) show a large array of levels of freedom, spanning from 1 to 7. For example, absence of direct democracy is associated with no freedom (e.g., China and Vietnam), with middle levels of freedom (e.g., Bolivia and Honduras), and with high levels of freedom (e.g., Costa Rica). A mild degree of direct democracy (scores 3–4 on the DDI) is associated with middle (e.g., Paraguay) to high (e.g., Germany and Finland) levels of political freedom, but not free countries are present in this category. Finally, higher levels of direct democracy (scores 5–7 on the DDI) are almost exclusively related with higher degrees of freedom (e.g., Australia, Italy, and Switzerland). The Philippines are the only outlier, since they show a higher level of DDI (score = 6) with respect to countries of similar level of freedom (score = 5).

We are now in a position to ask why in some countries direct democracy is more developed than others. Using the index presented in this section, we next investigate which factors promote direct democracy.

4 Model and Data

Using the index presented in the previous section, we now investigate the correlates of direct democracy. We estimate a number of models and specifications. Our first approach is to regress a model that considers demographic, economic, institutional and cultural variables. The model is the following:

where DDI is the variable defined in the previous Section, ECDEM is a vector of economic and demographic variables, INST is a vector of institutional variables, CULT is a vector of religious and cultural variables, and ε is an error term. ECDEM includes the log of GDP per capita in the year 2000, the log of population, the urbanization rate and a measure of ethnic fractionalization and finally the log of infant mortality. INST consists of two dummy variables for majoritarian and presidential systems. CULT includes the percentages of population that are Catholic and Muslim and the log of school attainment. We always add dummies for Latin American and Asian countries. The variable DDI comes from Kaufmann (2004), Hwang (2005), and Madroñal (2005). Data on ethno-linguistic fractionalization are taken from Alesina et al. (2003). Persson and Tabellini (2003) is the source of institutional variables, while data on education come from Barro and Lee (2010). Data on GDP comes from the Penn World Tables. For the year 2000, the remaining variables are taken from La Porta et al. (1999). Table 4 gives summary statistics for the variables involved in our analysis.

One problem with testing whether income and education affect direct democracy is that these variables might be affected by reverse causation. While cross-country literature does not have developed a way to take care of endogeneity between education and direct democracy,Footnote 4 we use the more established latitude as instrument for income, therefore estimating a Two-stage least square model (2SLS) as our baseline.Footnote 5 It is typical in the empirical literature to normalize the data in the (0, 1) space although the original data are categories. As a robustness check we re-estimate Eq. (1) with ordered probit.

5 Results

Table 5 reports the 2SLS results of Eq. (1). As income and direct democracy may be endogenously determined, we use the absolute value of the latitude as an instrument. We start with economic and demographic variables: the first column of Table 3 shows that income per capita is positive and significant, meaning that direct democracy is an ordinary good that is consumed more in richer societies. The results did not verify the idea posited by Aghion et al. (2004) that, in more fragmented societies, a group will restrict political liberty to impose control on the other groups. Ethnic fractionalization is negative as the theory predicts, but it is not significant. Both geographical dummies are significantly negative. Adding institutional and religious variables (column 2) strongly improves the model’s goodness of fit. While majoritarian voting rule and a presidential system do not appear to cause direct democracy institutions, the share of Catholics is significantly positive, though the size of the coefficient is very small. In the regression shown in column (3), we add the log of school attainment; the education variable reduces the significance of income, but does not change the main results of the model. Furthermore, the education variable is always significant, providing evidence for the link between education and democracy highlighted by Glaeser et al. (2007). The log of infant mortality and the urbanization rate (in columns 4, 5 and 6) are not significant. Overall, the goodness of fit is satisfactory and the joint significance of the variables is quite high.

A robustness check is provided in Table 6, where we estimate Eq. (1) with ordered probit, therefore taking into account the ordinal nature of the data on direct democracy. The most notable difference with respect to Table 5 is the significance of ethnic fractionalization, which has a negative coefficient as the theory of endogenous institutions suggests. Infant mortality and urbanization are also significant. All other variables have basically the same behaviour as the 2SLS estimates. Again, the joint significance of the variables is very high, but the pseudo-R2 is lower.

As highlighted in the previous section, an important caveat of the result we have presented is that they are based on a subjective index of direct democracy. Table 7 turns to the results of the count data estimates, employing the number of referendums that took place from 2000 to 2005, rather than the Direct Democracy Index, as the dependent variable. The source of these data is the Research Centre on Direct Democracy (2006). The findings do not differ much from the previous estimates. The log of income per capita and the share of Catholics remain positive and significant, although less so than in previous regressions. In contrast, the log of population becomes significantly positive. Log of school attainment, infant mortality and the urbanization rate are all significant. Some problems arise with the geographical dummies. The Latin America dummy is negative but often insignificant, whereas the Asia dummy is negative and sometimes significant, though not at a very high level. Although these results are consistent with the previous ones, we must regard them with care since we cannot control for endogeneity. Furthermore, the number of referenda is too simplistic a measure, failing to account for the quality of the democratic process (plebiscites are a form of direct democracy, but are ineffective at scrutinising the executive power).

6 Conclusions

In this paper we have addressed the issue of the determinants of direct democracy. In doing so, we have exploited a newly assembled dataset that encompasses 87 countries. We have estimated a number of models, with an emphasis on controlling for possible reverse causality effect with direct democracy. Across the many models we assess, direct democracy does not significantly relate to institutional variables like presidential system and majoritarian voting rules, and there is not large evidence supporting the influence of ethnolinguistic heterogeneity. These finding are poorly consistent with the theory of endogenous institutions provided by Aghion et al. (2004). The model of political insulation relates to the general institutional settings (including the role of the judiciary) that within the structure of the delegation of power allow blocking or passing a reform law. We restrict our analysis on two particular institutional arrangements as a form of insulation, specifically referenda and initiative use, which may directly block or pass legislation. It seems that moving from an indirect to a direct form of blocking legislation reduces the importance of racial fractionalization and nullifies the influence of majoritarian electoral rule and of the presidential system. Furthermore, it emphasizes the role of income and education in encouraging direct democracy instruments.

Taken as a whole, our findings seem to suggest that direct democracy institutions are stronger in countries with populations that are richer and more educated. This evidence is consistent with the Lipset’s view, and also with the empirical results presented in Glaeser et al. (2004) that development in human capital and in income is likely to improve political institutions. Data also show that political rights and political stability affect direct democracy, indicating that direct democracy comes after some political preconditions are fulfilled. Moreover, the share of Catholics seems to shape direct democracy. We interpret these findings as evidence of the Huntington view on the role of the Catholic Church in what he calls the third wave of democratization processes that took place in the last few decades. Starting from the 1960s, the Catholic Church becomes a powerful political force that leaves the conservative position encouraging the authoritarian regimes and the status quo in poor countries to promote the development of democratization processes (Huntington 1991). Finally, Latin America tends to be systematically related with less direct democracy.

Further work should address the issue of time, therefore exploring changes of direct democracy in a panel data setting, both with qualitative and quantitative indicators. Furthermore, a distinction between social and economic issues on the one hand and individual rights issues on the other hand needs also to be investigated.

Notes

- 1.

The empirical analyses of direct democracy have mainly discussed the relationship between initiatives and referendums and government spending (Matsusaka 1995, 2004; Feld and Matsusaka 2003), and the impact of direct democracy institutions on economic performance (Feld and Savioz 1997; Blomberg et al. 2004; Frey et al. 2001). Most of these studies deal with either Switzerland or the US states.

- 2.

Formally, the political leader has to implement reforms, but voters do not know ex ante whether the executive will reform or just expropriate rents from the voters. This degree of insulation is captured by a (super)majority of individuals (M) that can block the action of the leader (expropriation or reform) once the aggregate shock on preferences is realized. If M is high, only a large majority of voters can block the reform. In contrast, a low M means that, when in office, the leader is kept in check by small fractions of the electorate.

- 3.

See also de Figureido (2002).

- 4.

Glaeser and Saks (2006) in analyzing corruption in America utilize historical factors like Congregationalism in 1890 as instrument for the level of schooling. Yet, this kind of instruments is specific for the country they examine, and furthermore they estimate panel data from 1976 to 2002.

- 5.

Acemoglu et al. (2008) address the same issue concerning democracy in a panel setting, by using past savings rates and changes in the incomes of trading partners.

References

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., Robinson, J. A., & Yared, P. (2008). Income and democracy. American Economic Review, 98, 808–842.

Aghion, P., Alesina, A., & Trebbi, F. (2004). Endogenous political institutions. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119, 565–612.

Alesina, A., Devleeshauwer, A., Easterly, W., Kurlat, S., & Warcziarg, R. (2003). Fractionalization. Journal of Economic Growth, 8, 155–194.

Altman, D. (2011). Direct democracy worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Anckar, D. (2004). Direct democracy in microstates and small island states. World Development, 32, 379–390.

Barro, R., & Lee, J. W. (2010). A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950–2010. Journal of Development Economics, 104, 184–198.

Barry, B. (1978). Sociologists, economists, and democracy. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Blomberg, S. B., Hess, G. D., & Weerapana, A. (2004). The impact of voter initiatives on economic activity. European Journal of Political Economy, 20, 207–226.

Breuer, A. (2007). Institutions of direct democracy and accountability in Latin America's presidential democracies. Democratization, 14, 554–579.

Castles, F. G., & Mair, P. (1984). Left–right political scales: some ‘Expert’ judgments. European Journal of Political Research, 12, 73–88.

Cox, G. W. (1997). Making votes count. Strategic coordination in the world’s electoral systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dahl, R. A. (1971). Polyarchy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

de Tocqueville, A. (1835). Democracy in America. London: Saunders and Otley.

Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Feld, L. P., & Matsusaka, J. G. (2003). Budget referendums and government spending: Evidence from Swiss Cantons. Journal of Public Economics, 87, 2703–2724.

Feld, L. P., & Savioz, M. R. (1997). Direct democracy matters for economic performance: An empirical investigation. Kyklos, 50, 507–538.

Finley, M. I. (1985). Democracy ancient and modern. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Fish, M. S., & Kronig, M. (2009). The handbook of national legislatures. A global survey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Frey, B. S., Kucher, M., & Stutzer, A. (2001). Outcome, process and power in direct democracy. New econometric results. Public Choice, 107, 271–293.

Gallagher, M., & Mitchell, P. (Eds.). (2005). The politics of electoral systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Glaeser, E. L., La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2004). Do institutions cause growth? Journal of Economic Growth, 9, 271–303.

Glaeser, E. L., & Saks, R. E. (2006). Corruption in America. Journal of Public Economics, 90, 1053–1072.

Glaeser, E. L., Ponzetto, G., & Shleifer, A. (2007). Why does democracy need education? Journal of Economic Growth, 12, 77–99.

Huntington, S. (1991). The third wave: Democratization in the twentieth century. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Hwang, J.-Y. (2005). Direct democracy in Asia: A reference guide to the legislation and practice. Taiwan: Taiwan Foundation for Democracy Publication.

Katz, R. S., & Crotty, W. (Eds.). (2005). Handbook of party politics. London: Sage.

Kaufmann, B. (2004). Initiative and referendum monitor 2004/2005. Amsterdam: IRI Europe.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1999). The quality of government. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 15, 222–279.

Landes, D. (1998). The wealth and poverty of nations. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

Lijphart, A. (1968). Typologies of democratic systems. Comparative Political Studies, 1, 3–44.

Lijphart, A. (2012). Patterns of democracy. Government forms and performance in thirty-six countries. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Lipset, S. M. (1959). Some social requisites of democracy: Economic development and political legitimacy. American Political Science Review, 53, 69–105.

Madroñal, J. C. (2005). Direct democracy in Latin America. Madroñal: Mas Democracia and Democracy International.

Manin, B. (1997). The principles of representative government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Matsusaka, J. G. (1995). Fiscal effects of the voter initiative: Evidence from the last 30 years. Journal of Political Economy, 103, 587–623.

Matsusaka, J. G. (2004). For the many or the few: The initiative, public policy, and American democracy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Matsusaka, J. G. (2005). Direct democracy works. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19, 185–206.

Olson, M. (1965). The logic of collective action. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2003). The economic effects of constitutions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Przeworski, A., Alvarez, M., Cheibub, J., & Limongi, F. (2000). Democracy and development: Political institutions and well-being in the world 1900–1950. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Przeworski, A., & Limongi, F. (1993). Political regimes and economic growth. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 7, 51–69.

Putnam, R. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Research Centre on Direct Democracy. (2006). Database on direct democracy. University of Geneva. www.c2d.unige.ch

Riker, W. H., & Ordeshook, P. C. (1973). An introduction to positive political theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Scarrow, S. E. (2001). Direct democracy and institutional change. A comparative investigation. Comparative Political Studies, 34, 651–665.

Sartori, G. (1976). Parties and party systems: A framework for analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1942). Capitalism, socialism and democracy. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Tsebelis, G. (2002). Veto players: How political institutions work. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Fiorino, N., Ricciuti, R., Venturino, F. (2017). Measuring Direct Democracy. In: Schofield, N., Caballero, G. (eds) State, Institutions and Democracy. Studies in Political Economy. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44582-3_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44582-3_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-44581-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-44582-3

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)