Abstract

In 15%t of patients of patients developing acute pancreatitis, the disease progresses to a severe necrotising pancreatic/peri-pancreatic process accompanied by a systemic inflammatory response resulting in a life-threatening disorder with a reported mortality exceeding 20 %. Bacterial infection of pancreatic necrosis is the most frequent local complication and is responsible for the majority of deaths from organ failure. The treatment is by pancreatic necrosectomy. Although traditionally performed by laparotomy, in the last few decades, minimal access and radiologically-guided approaches have been used increasingly with published reports which collectively indicate reduced morbidity (bleeding and intestinal injuries) and improved survival. The author’s experience is with the operation of infracolic pancreatic necrosectomy followed by continuous irrigation and drainage of the lesser sac with the Beger’s technique.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Severe necrotizing acute pancreatitis

- Early and late subtypes

- Bacterial infection

- Options for surgical/endoscopic

- Radiological management

- Laparoscopic infracolic necrosectomy

1 Introduction and Pathogenesis

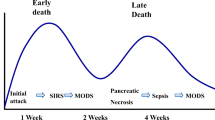

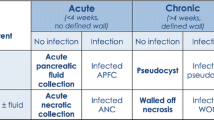

Whilst in the majority of patients, acute pancreatitis is a self-limiting disease, in 15–20 % of patients a severe necrotising pancreatic/peri-pancreatic process develops accompanied by a systemic inflammatory response characterised by an activated cytokine cascade and including a destructive exaggerated leukocyte tissue response, resulting in a life-threatening disorder with a reported mortality exceeding 20 % [1]. There are two subtypes of the necrotizing severe disease: (i) early severe acute pancreatitis (ESAP) defined as presence of organ failure on admission or soon after and accounts for 30 % of patients and (ii) late or delayed severe acute pancreatitis. The main factor predisposing to ESAP is extensive pancreatic necrosis (odds ratio, 3.8) and in practice, ESAP more frequently requires necrosectomy and carries an overall higher mortality than the delayed onset severe disease [2]. There are different serum markers used as indices of severe pancreatitis: interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, interleukin-18, s-ICAM, C-reactive protein, anti-proteases, trypsinogen activation peptide (TAP), carboxypeptidase B activation peptide (CAPAP), PMN-elastase and activated complement factors.

Bacterial infection of pancreatic necrosis is the most frequent local complication and is associated with the development of systemic complications which are responsible for the majority of deaths [3, 4]. Organ failure is more frequent in patients with infected necrosis and in those with extensive pancreatic necrosis. The aetiology of the pancreatitis influences the microbiology of infected pancreatic necrosis and cultures are more often positive in biliary than alcoholic disease (74 % vs. 32 %). Gram-positive bacteria predominate in alcoholic pancreatitis whereas Gram-negative bacteria account for the majority of infections in severe biliary pancreatitis. Candida infection of the pancreatic necrosis is a major problem and is associated with a poor prognosis [5]. Recent clinical studies have confirmed that gut permeability is increased in patients with severe acute pancreatitis (impaired gut barrier function) with increased risk of bacterial/endotoxin translocation from the gut to the systemic circulation [6]. The early use of antibiotics and continuous regional arterial infusion of protease inhibitor has been proposed in order to reduce the mortality [7–13]. The best available guidelines for the management of severe acute pancreatitis are those proposed by the Japanese in 2009 (see Table 24.1 – reference [14]).

1.1 Treatment Options

Although necrosectomy is traditionally performed by laparotomy [15–18], in the last 5–10 years minimal access and radiologically-guided approaches [19–23] are increasingly used and the growing number of published reports indicates that they reduce morbidity (bleeding and intestinal injuries) and improve survival significantly. The retroperitoneal approach (RPA) allows direct and complete removal of necrotic infected tissues and is currently popular [17, 24], but the author’s experience is with the operation of infracolic pancreatic necrosectomy [25, 26] with continuous irrigation and drainage of the lesser sac with the Beger’s technique (reference [16]). This procedure is described fully in this chapter. It is also used to drain infected pseudocysts via a cysto-jenunostomy.

2 Indications for Surgical Treatment and Treatment Options

Treatment of sterile necrosis should be conservative in the first instance and should include systemic high dose antibiotic (elaborate). However, persistent organ failure that does not respond to therapy in the presence of extensive pancreatic necrosis (>50 %) even if this is not infected is an indication for necrosectomy. Infected pancreatic necrosis diagnosed by radiologically fine needle aspiration of the necrotic area for bacteriology (FNAB) constitutes an absolute indication for necrosectomy.

3 Preoperative Work-Up

Patients with established pancreatic necrosis require serial contrast enhanced computed tomography or preferably MRI and if infection is suspected, FNAB is essential. In some centres ultrasound is used for procurement of FNAB. MRI is increasingly preferred to contrast-enhanced CT as serial imaging is usually needed in the individual patient and this creates radiation risks with CT. There are still unresolved issues in the management of severe pancreatic necrosis, including antibiotic prophylaxis, indications for and frequency of repeat imaging and FNAB, and the role of enteral feeding. However a recent Cochrane review reported that early antibiotic prophylaxis reduces the risk of infection of pancreatic necrosis.

4 Laparoscoic Infracolic Necrosectomy

The technique of laparoscopic necrosectomy was first undertaken in Dundee in 1998. It reproduces the classical open necrosectomy to date has been accompanied by reduced morbidity and a significant increase in survival rate (90 %). It may be carried out totally laparoscopically, or through the hand-assisted laparoscopic approach.

Special Instruments

The procedure is greatly facilitated by 30° forward oblique laparoscope, curved co-axial instruments and flexible ports, prehensile grasper for atraumatic gasping of the transverse colon and good pulsed irrigation system.

Position of Patient and Ports

The patient is placed in the supine position with the surgeon and camera person on the right side of the patient and the assistant and scrub nurse on the opposite side (Fig. 24.1).

Following induction of capnoperitoneum, the 11.0 mm optical port is inserted through the umbilicus and a 10 mm 30° forward oblique laparoscope is introduced. Two flexible instruments ports (for use with curved coaxial instrument) are then placed on each side of the laparoscope. These serve as the instrument ports for the surgeon (Fig. 24.2).

The curved coaxial instruments (Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany) greatly facilitate the manipulations particularly when the lesser sac is entered, but the procedure can be carried out with straight laparoscopic instruments.

5 Steps of the Laparoscopic Infracolic Necrosectomy

5.1 Elevation of Transverse Colon

This initial step provides the necessary infracolic exposure of the lesser sac. The greater omentum is lifted upwards by two atraumatic graspers of intestinal clamps until the transverse colon is exposed behind it. This may require initial division of adhesions binding the greater omentum to loops of the small intestine.

The exposed transverse colon is then grasped by a prehensile articulating grasper (Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany) or large atraumatic intestinal clamp and elevated upwards to expose the inferior surface of the transverse mesocolon and hold it stretched over the bulging lesser lessee sac and contents behind it. At this stage the patient is tilted slightly head-down to improve the exposure. The advantage of the prehensile grasper is that it allows ‘ring holding’ of the transverse colon and hence reduces the risk of damage to the bowel.

The transverse mesocolon is the rolled over to enhance the tense bulge in the lesser sac containing the pancreatic necrosis and peri-pancreatic fluid which becomes clearly visible at its lower margin as a ‘blue line’ stretching horizontally up to the duodeno-jejunal junction/ligament of Treitz (Fig. 24.3).

5.2 Division of the Peritoneum of the Inferior Leaf of the Transverse Colon

The peritoneum at the base of the inferior leaf of the transverse mesocolon to the left of the middle colic vessels and over the bulging lesser sac is coagulated and divided along the blue line by curved scissors to expose the bulging ‘fascia’ encasing the pancreatic sequestrum and peri-pancreatic fluid.

The lesser sac fluid surrounding the pancreatic infected necrosis is identified and confirmed by needle puncture with aspiration of the fluid/pus which is sent for aerobic and anaerobic culture and sensitivity (Fig. 24.4).

5.3 Opening the Lesser Sac and Aspiration of Peri-Pancreatic Space

Having confirmed the space by needle aspiration, the fibrous layer containing the fluid and the necrosed pancreas and peripancreatic fat is divided by scissors just enough to enable the insertion of the sucker into the lesser sac. This is used to aspirate and wash the closed lesser sac before it is opened further for the necrosectomy. This repeated aspiration and irrigation by at least 1.0 l of saline of the closed lesser sac is very important for reducing the risk of significant bacterial contamination of the peritoneal cavity.

Thereafter, the opening in the lesser sac is sac is extended (Fig. 24.5) to provide sufficient access for the necrosectomy, taking care to avoid damage to the middle colic vessels.

5.4 Necrosectomy

The visually-guided necrosectomy is carried by a combination of ‘pulsed pressure’ irrigation, suction and piecemeal removal of the necrotic segments using non-crushing/non-tooth graspers or intestinal clamp. The co-axial curved Babcocks and intestinal claps instruments are ideally suited for insertion into the lesser sac and grasping the pancreatic slough.

The irrigation is used both to clean the cavity and to dislodge the necrotic pancreatic tissue. Only the loose or loosened necrotic pancreatic slough is grasped and removed. The necrosectomy entails piecemeal removal of all the loose sequestrum provided there is no bleeding when the necrosectomy is stopped. Adherent slough must not be removed forcibly, i.e., only picking and gentle detachment is allowed. Once the necrosectomy is completed, the cavity is given a final saline wash and inspected by the laparoscope.

5.5 Evacuation of the Pancreatic Slough

The necrotic segments may be removed piecemeal each time a fragment is picked up. However, to reduce instrument traffic it is better to place them all in a water and rip-proof bag, which is exteriorised at the end of the operation through the wound made to introduce the large port in the left flank. Apart from anything else, this saves on operating time, and probably reduces contamination.

5.6 Insertion of Drains for Closed Irrigation of the Lesser Sac

This is a crucial step. Large silicon (10 mm) inflow and outflow drains are inserted through separate stab wounds and their internal ends guided inside the lesser sac. Both drains are secured to the edges of the opening in the fibrous capsule by absorbable sutures to prevent dislodgement from the lesser sac into the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 24.6). They are also fixed to the exit site by skin sutures.

These drains should lie side by side or on top of each other. They are used for postoperative hypertonic crystalloid irrigation of the lesser sac. For this reason, the irrigation system should be checked by injecting saline through the inflow drain. Once the necrosectomy cavity has filled fluid, the turbid effluent should return via the outflow drain.

The transverse colon and greater omentum are then released and placed gently on top of the drains and the root of the small bowel mesentery.

All the port wounds are irrigated with antibiotic solution (gentamycin) prior to closure.

5.7 Postoperative Management

The patients are nursed in HDU or ICU (depending on need for respiratory support) after surgery. The irrigation of the lesser sac (2 l per 24 h) with hyperosmolar dialysate solution is continued until the returning fluid is clear of necrotic bits, usually 7–10 days. Antibiotic therapy (imipenem) is maintained for 7 days.

References

Isenmann R, Rau B, Beger HG. Early severe acute pancreatitis: characteristics of a new subgroup. Pancreas. 2001;22(3):274–8.

Gloor B, Muller CA, Worni M, Martignoni ME, Uhl W, Buchler MW. Late mortality in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2001;88(7):975–9.

Raty S, Sand J, Nordback I. Difference in microbes contaminating pancreatic necrosis in biliary and alcoholic pancreatitis. Int J Pancreatol. 1998;24(3):187–91.

Buchler MW, Gloor B, Muller CA, Friess H, Seiler CA, Uhl W. Acute necrotizing pancreatitis: treatment strategy according to the status of infection. Ann Surg. 2000;232(5):627–9.

Gotzinger P, Wamser P, Barlan M, Sautner T, Jakesz R, Fugger R. Candida infection of local necrosis in severe acute pancreatitis is associated with increased mortality. Shock. 2000;14(3):320–3.

Juvonen PO, Alhava EM, Takala JA. Gut permeability in patients with acute pancreatitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35(12):1314–8.

Nordback I, Sand J, Saaristo R, Paajanen H. Early treatment with antibiotics reduces the need for surgery in acute necrotizing pancreatitis--a single-center randomized study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5(2):113–8.

Slavin J, Neoptolemos JP. Antibiotic prophylaxis in severe acute pancreatitis--what are the facts? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2001;386(2):155–9.

Gloor B, Schmidt O, Uhl W, Buchler MW. Prophylactic antibiotics and pancreatic necrosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2001;3(2):109–14.

Shrikhande S, Friess H, Issenegger C, Martignoni ME, Yong H, Gloor B, Yeates R, Kleeff J, Buchler MW. Fluconazole penetration into the pancreas. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44(9):2569–71.

Villatoro E, Bassi C, Larvin M. Antibiotic therapy for prophylaxis against infection of pancreatic necrosis in acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Rev. Prepared and maintained by The Cochrane Collaboration and published in The Cochrane Library. 2009; Issue 1. http://www.thecochranelibrary.com.

Matsukawa H, Hara A, Ito T, Fukui K, Sato K, Ichikawa M, Yoshioka M, Seki H, Takeda K, Sunamura M, Shibuya K, Kobari M, Matsuno S. Role of early continuous regional arterial infusion of protease inhibitor and antibiotic in nonsurgical treatment of acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Digestion. 1999;60 Suppl 1:9–13.

Takeda K, Matsuno S, Ogawa M, Watanabe S, Atomi Y. Continuous regional arterial infusion (CRAI) therapy reduces the mortality rate of acute necrotizing pancreatitis: results of a cooperative survey in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2001;8(3):216–20.

Isaji S, Takada T, Kawarada Y, et al. JPN Guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: surgical management. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13(1):48–55. doi:10.1007/s00534-005-1051-7. PMCID: PMC2779397.

Lankisch PG, Struckmann K, Assmus C, Lehnick D, Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB. Do we need a computed tomography examination in all patients with acute pancreatitis within 72 h after admission to hospital for the detection of pancreatic necrosis? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36(4):432–6.

Beger HG, Rau B, Isenmann R. Necrosectomy or anatomically guided resection in acute pancreatitis. Chirurg. 2000;71(3):274–80.

Nakasaki H, Tajima T, Fujii K, Makuuchi H. A surgical treatment of infected pancreatic necrosis: retroperitoneal laparotomy. Dig Surg. 1999;16:506–11. doi:10.1159/000018777.

Wyncoll DL. The management of severe acute necrotising pancreatitis: an evidence-based on review of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25(2):146–56.

Gouzi JL, Bloom E, Julio C, Labbe F, Sans N, el Rassi Z, Carrere N, Pradere B. Percutaneous drainage of infected pancreatic necrosis: an alternative to Surgery. Chirurgie. 1999;124(1):31–7.

Carter CR, McKay CJ, Imrie CW. Percutaneous necrosectomy and sinus tract endoscopy in the management of infected pancreatic necrosis: an initial experience. Ann Surg. 2000;232(2):175–80.

Kam A, Young N, Markson G, Wong KP, Brancatisano R. Case report: inappropriate use of percutaneous drainage in the management of pancreatic necrosis. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14(7):699–704.

Oria A, Ocampo C, Zandalazini H, Chiappetta L, Moran C. Internal drainage of giant acute pseudocysts: the role of video-assisted pancreatic necrosectomy. Arch Surg. 2000;135(2):136–40.

Horvath KD, Kao LS, Wherry KL, Pellegrini CA, Sinanan MN. A technique for laparoscopic-assisted percutaneous drainage of infected pancreatic necrosis and pancreatic abscess. Surg Endosc. 2001;15(10):1221–5.

Castellanos G, Serrano A, Pinero A, Bru M, Parraga M, Marin P, Parrilla P. Retroperitoneoscopy in the management of drained infected pancreatic necrosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53(4):514–5.

Cuschieri SA, Jakimowicz JJ, Stultiens G. Laparoscopic infracolic approach for complications of acute pancreatitis. Semin Laparosc Surg. 1998;5(3):189–94.

Hamad GG, Broderick TJ. Laparoscopic pancreatic necrosectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2000;10(2):115–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Cuschieri, A. (2017). Treatment of Severe Complicated Pancreatitis. In: Bonjer, H. (eds) Surgical Principles of Minimally Invasive Procedures. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-43196-3_24

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-43196-3_24

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-43194-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-43196-3

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)